Drums on Fire | Interview with Ginger Baker

Ginger Baker passed away at the age of 80 on October 6th. Musical appreciations, remembrances and heartfelt tributes poured in from fans, fellow musicians and even a few of those who were the object of Baker’s scorn. What follows below is a story I wrote on Baker in 1999, based on an interview with the legendary British drummer when he was 60. It was the only time I interviewed Baker.

Since that article, Baker recorded two more albums of African music just after the 1999 release Coward of the County, and in 2014 released what would be his last album, Why?, a jazz album. There were also the Cream reunion shows in 2005 and resulting live DVD and album Royal Albert Hall London May 2-3-5-6, 2005 and the documentary film Waiting for Mr. Baker in 2012. I have purposely chosen to not update the article, which originally appeared in the now-defunct Inside Connection magazine. It offers a snapshot of a time in Baker’s idiosyncratic and varied career. The Baker I encountered was at times a little cranky and not always forthcoming, but most of the time fairly open and willing to talk. This is the first appearance of the article online.

Long-distance phone calls from such a far-flung place as South Africa can still be something of a challenge. Such was the case for me this past summer when I had a chance to talk to Rock and Roll Hall of Fame member Ginger Baker. The former Cream and Blind Faith drummer talked to me from his 59-acre home in Karkloof, South Africa, which is part of the Karkloof Valley, northwest of Durban. He spoke about Coward of the County, his latest project and third Atlantic Record’s outing. A collaboration between the 60- year-old legend and the Denver Jazz Quintet, it also includes clarinet and sax contribution from hot young jazzman James Carter. Though originally scheduled to be recorded in March of 1998, the sessions were postponed when Baker had shoulder surgery for an old polo injury. Recordings were delayed a second time after a horse threw Baker and he suffered three broken ribs. Sessions finally got off the ground in September of 1998. Baker’s current residency in South Africa came about after one of the nastiest deportation cases one is likely to hear about. Apparently, one of Baker’s fellow polo players, from his former home in Parker, Colorado, just outside Denver, tipped off INS officials that the drummer was employing a London-born woman named Liz Ledsham, who did not have a green card. Following Baker’s blasting of the feds on a Denver-based radio show and a heavy-handed investigation, Ledsham was deported. Having lived in America for ten years on a work visa (two marijuana arrests in the early ‘70s prevented Baker from obtaining a green card). Baker was subsequently refused entry back into the states following a vacation in the fall of 1998. To make matters worse, the incident prompted the I.R.S. to become involved. It is reportedly demanding huge sums of taxes on income that Baker claims he never earned in the U.S.

A few months after the release of Coward of the County in the spring of 1999, bad luck continued to haunt Baker. In July, he came down with a very high fever that doctors initially thought was from pneumonia but as of this writing still have not successfully been diagnosed. The illness dragged on for weeks, and rest and medication still have not cured him completely. Such a string of illness and personal turmoil could easily daunt many an individual, not to mention a 60-year-old rock drummer who suffered through a 20-year on-and-off battle with cocaine and heroin (Baker has been drug-free for 18 years). Yet, Baker is sporadically promoting his excellent new album and hopes to be performing again in South Africa (he lived in Nigeria in the early ‘70s) by year’s end.

“Cream played great music, but I never considered them rock ‘n’ roll. It was a jazz-blues thing. Eighty percent of the music was improvised. They were a one-off thing.”

We began our discussion by talking about the cut “Cyril Davies” from Baker’s new album. His comments dealt mostly with how his songwriting process works. “That song is something that has been going ‘round my head for years,” he admitted. “It was inspired by something Cyril wrote years ago called ‘Spooky but Nice.’ Most of the stuff that I write stays in my head for several years before I actually write it down.” Baker first played with Davies in Alexis Korner’s Blues Incorporated. Their first meeting was not an auspicious one. According to Baker, Davies didn’t want him in the group. However, after Baker first rehearsed with the group, Davies was duly impressed and warmly welcomed him into the fold with open arms. Blues Incorporated, together from 1962 until 1966, included at various times Baker, Jack Bruce, Long John Baldry, future Manfred Mann vocalist Paul Jones and future Rolling Stones members Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, Brian Jones and Charlie Watts. In recalling his Blues Incorporated days, Baker said, “There were good times and bad times. It was the first time anyone mixed straight jazz and straight blues players. There were great crowds and a whole new music evolved.” When asked if there was ever any tension within the group between the jazz and blues camps, Baker emphatically said, “No.” After leaving Blues Incorporated and before joining the Graham Bond Organization, Jack Bruce and Ginger Baker, together with Graham Bond, were part of the Johnny Birch Octet. The Graham Bond Organization was formed in 1963 and included Baker, Bruce, Bond and future Mahavishnu Orchestra guitarist John McLaughlin. Baker stayed with the group until late 1965 before forming Cream with Bruce and Eric Clapton in 1966.

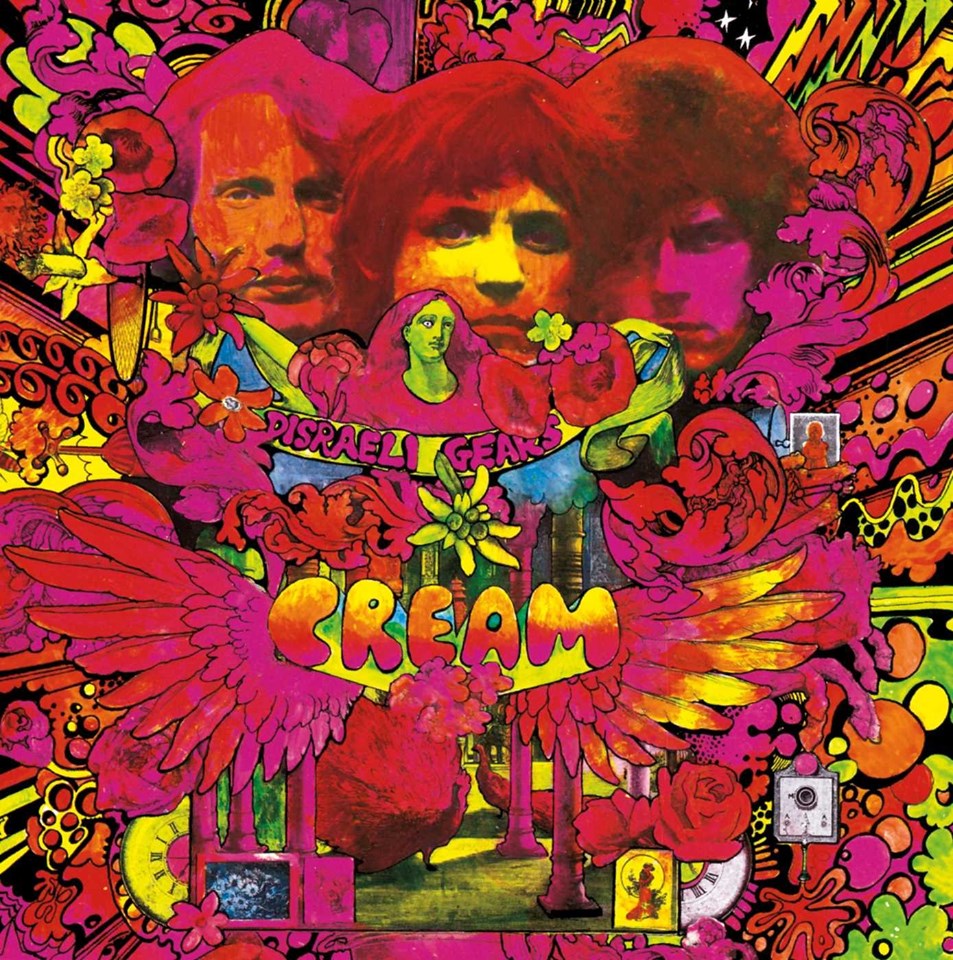

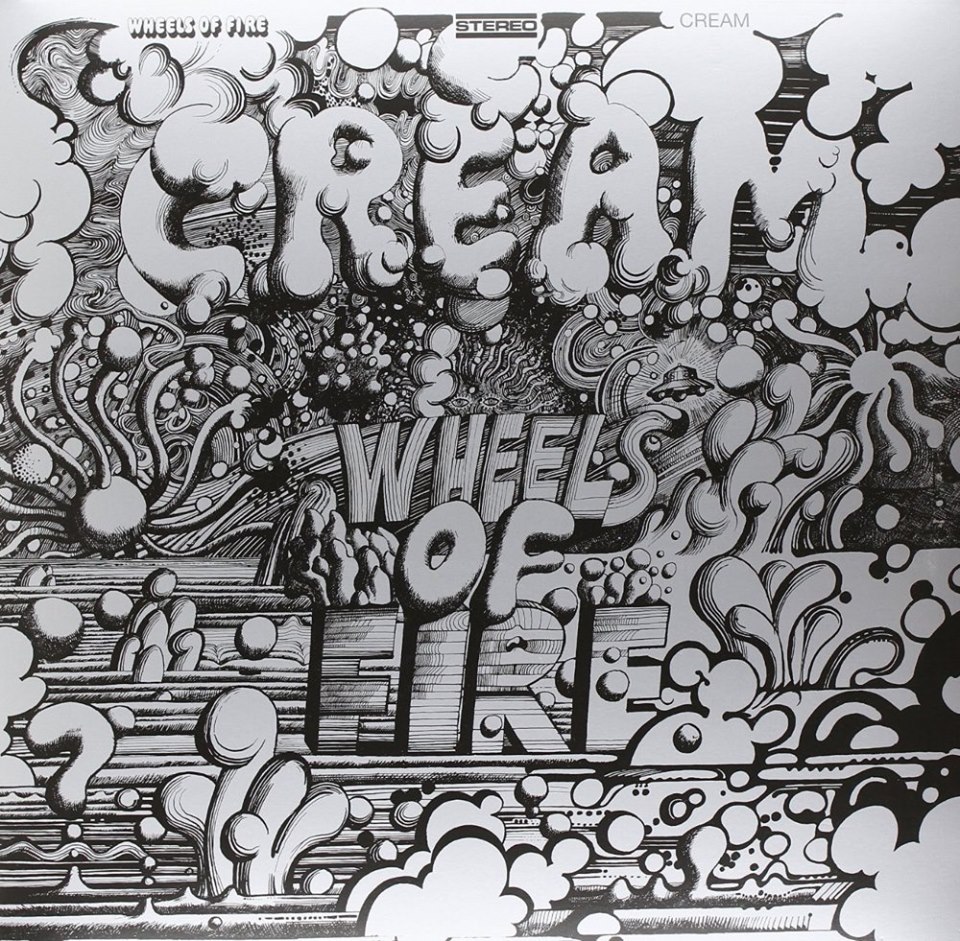

Cream’s short run, from July of 1966 until its farewell concert at the Royal Albert Hall in London on November 26, 1968, could best be described as the era of rock’s first supergroup. After Baker and Bruce had a falling out, Bruce joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. Eric Clapton, having played with the Yardbirds and the Bluesbreakers, was looking to put a band together, and after a chance meeting with Baker, suggested getting Jack Bruce in a group. Clapton convinced Baker to settle his differences with Bruce. Bruce then joined the group and Clapton named the band Cream since they had all been dubbed the “cream” of British rock musicians. The group’s studio works consist of its surprisingly powerful debut, Fresh Cream, its American-recorded studio master-work, Disraeli Gears, and the studio cuts from Wheels Of Fire. When talking about Cream, Baker clearly has mixed emotions. In response to rock music in general, he said, “I am no longer interested in all that.” He felt that the Korner and Bond bands were the forerunners of what Cream and Jimi Hendrix went on to do, and in regard to Cream specifically, he said, “Cream just happened to be the band that took off. Cream played great music, but I never considered them rock ‘n’ roll. It was a jazz-blues thing. Eighty percent of the music was improvised. They were a one-off thing.”

“Jazz and blues are the same bloody thing.”

When asked if he had any hand in the Cream box set, or if not, if he had heard it, he responded, “No” to both questions and then added, “That was the past.” For anyone who has lost touch with Baker since his days with Cream or as part of the self-titled 1969 album Blind Faith recorded with Clapton, Steve Winwood and Rick Grech, he has been very busy. There was Ginger Baker’s Air Force in the early ‘70s, which included contributions from Bond, Grech, Winwood and Denny Laine, the Baker-Gurvitz Army in the mid-’70s and the Ginger Baker and Friends and Ginger Baker and Band projects of the late ‘70s and early ‘80s. Throughout the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, there was also music he recorded in Africa with Ginger Baker and African Force. Baker even recorded with African music god Fela Kuti in the early ‘70s. In 1991, Cream was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Any of the bitter memories of the group’s tortured breakup had virtually evaporated. Their performance was revelatory and Clapton, clearly moved during their acceptance speech, nearly broke down in tears. Baker told John McDermott for the liner notes for the Cream box set, “It was fantastic. It was as if we had just taken a holiday. The magic was still there after all these years.” When I asked him about it, he added, “That was fun.” In 1994 Baker rejoined fellow Cream alumnus Jack Bruce for the live Cities album as part of the BBM group, which also included guitarist Gary Moore. The group also recorded the studio album Around the Dream in 1995. The reunion with Bruce unfortunately was not a pleasant experience for Baker. He indicated that near the end, “(Bruce) wasn’t very happy with the last recordings,” and felt like his role in the project (as more or less, a session musician), was something “he didn’t like.” Despite such a long, varied and successful career, for Baker and a host of music critics, Baker’s next three albums are considered some of the best music he ever made. In 1994 he joined forces with avant-jazz guitarist Bill Frisell and renowned jazz bassist and the mastermind behind Quartet West bassist Charlie Haden (whom Baker characterized as a “great musician”) to record Going Back Home, the first of three jazz albums for Atlantic. The trio’s followup in 1996, Falling Off the Roof (so entitled as a result of an accident Baker suffered while actually fixing his roof), received reviews that were even more positive than his previous effort. With all the legal and medical events swirling around the release of Coward of the County, the fact that Baker has come up with yet another superb jazz outing should not be overlooked. The album is less experimental than previous Baker jazz outings and has a cool and languid feel that is also very upbeat and accessible. Despite the large number of jazz musicians with whom Baker has played, there are “several hundred” he would still like to work with, although he refused to mention who any of them might be. As for why he plays jazz, he said, “I don’t play jazz to make money,” and indicated that he doesn’t play any of the old rock material from his past. As for the blues, he laughed and said, “Jazz and blues are the same bloody thing. Twelve-bar blues is the same thing that jazz players have been improvising on since 1920!”

There is no doubt that Baker will be playing jazz again in South Africa, and he indicated that there are some jazz clubs with “lots of good players” there. For now, he is content to “play a bit of polo.” He wants to work with the musicians from his latest album, but said, “I don’t intend to ever return to America.” Clearly uncomfortable making any future plans or discussing any possibilities, Baker concluded our chat by saying, “It’s in the hands of Allah.”

– Steve Matteo

Strange and difficult man but a true drumming legend. Nice to see an article of him here after his recent passing.