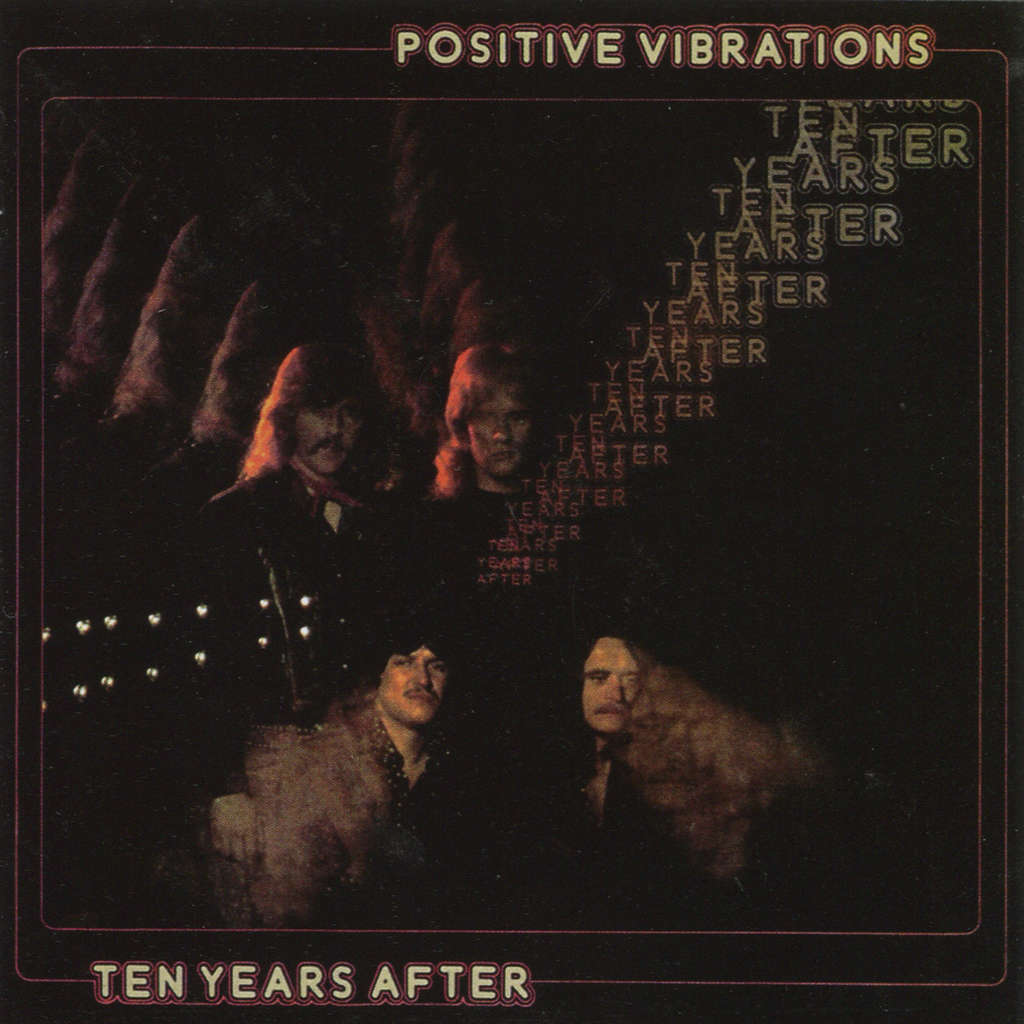

Ten Years After | Leo Lyons | Interview

Leo Lyons is a legendary Ten Years After bassist. He’s also well regarded record producer.

To begin with, when and where were you born and was music a big part of your life in Lyons household?

Leo Lyons: I was born 1943 in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire in the heart of the East Midlands coalfields, United Kingdom. The World was at war and my father was away serving in the army. He was killed in action in 1944 when I was only nine months old.

Most of the men in the family were coal miners but there was a love for music in the family. My grandfather was an accomplished singer and brass band player. His brother Morgan Kingston, also a former miner, was a professional operatic tenor and Columbia recording artiste. I just read recently that he sang for President Woodrow Wilson at The White House.

I never knew either of them but I remember, as a very young child, listening to my Great Uncle’s records on a wind up gramophone.

For some reason amongst the record collection were 78’s of Lead Belly and Jimmy Rogers. That was the first time I heard a guitar played. The sound blew me away and I tried several times to make a cigar box guitar with no success.

Like a lot of my contemporaries I loved the Skiffle Music craze that swept the UK in the 1950’s. In particular I liked Lonnie Donegan. I desperately wanted a guitar but could not afford to buy one. There was a banjo that once belonged to my Grandfather and I started playing that.

One of the earliest bands you were part of were The Phantoms and a bit later The Atomites. What did you play?

When I finally got a guitar I started lessons with local teacher Frank Wooley. He introduced me to some of his other pupils who had a band called ‘Paul Dennis And The Phantoms’. They needed a bass player and they invited me to join them. At first I played bass lines on an electrified Dobro guitar belonging to my guitar teacher.

I eventually raised some money by selling my bicycle and bought a Hofner Senator bass guitar on Hire Purchase (deferred payment). From that moment on I never looked back. I knew bass was the instrument I wanted to play. My guitar teacher Frank was disappointed and said that it was wasting my talent.

‘The Phantoms’ were a hobby band and played gigs just for fun, usually relatives weddings, but on one show I was spotted by the manager of ‘The Atomites’, a popular local band who were intending to turn professional and move to London. I was asked if I’d like to join the band and I did. We changed our name to ‘The Jaycats’ and later ‘the Jaybirds’

In the early sixties you worked as a session musician and toured as a sideman with many acts.

The Jaybirds moved to London in 1961 to seek fame and fortune but it was not an instant success. We returned home several times as failures only to return again with different line ups eventually downsizing to a three piece for reasons of economy.

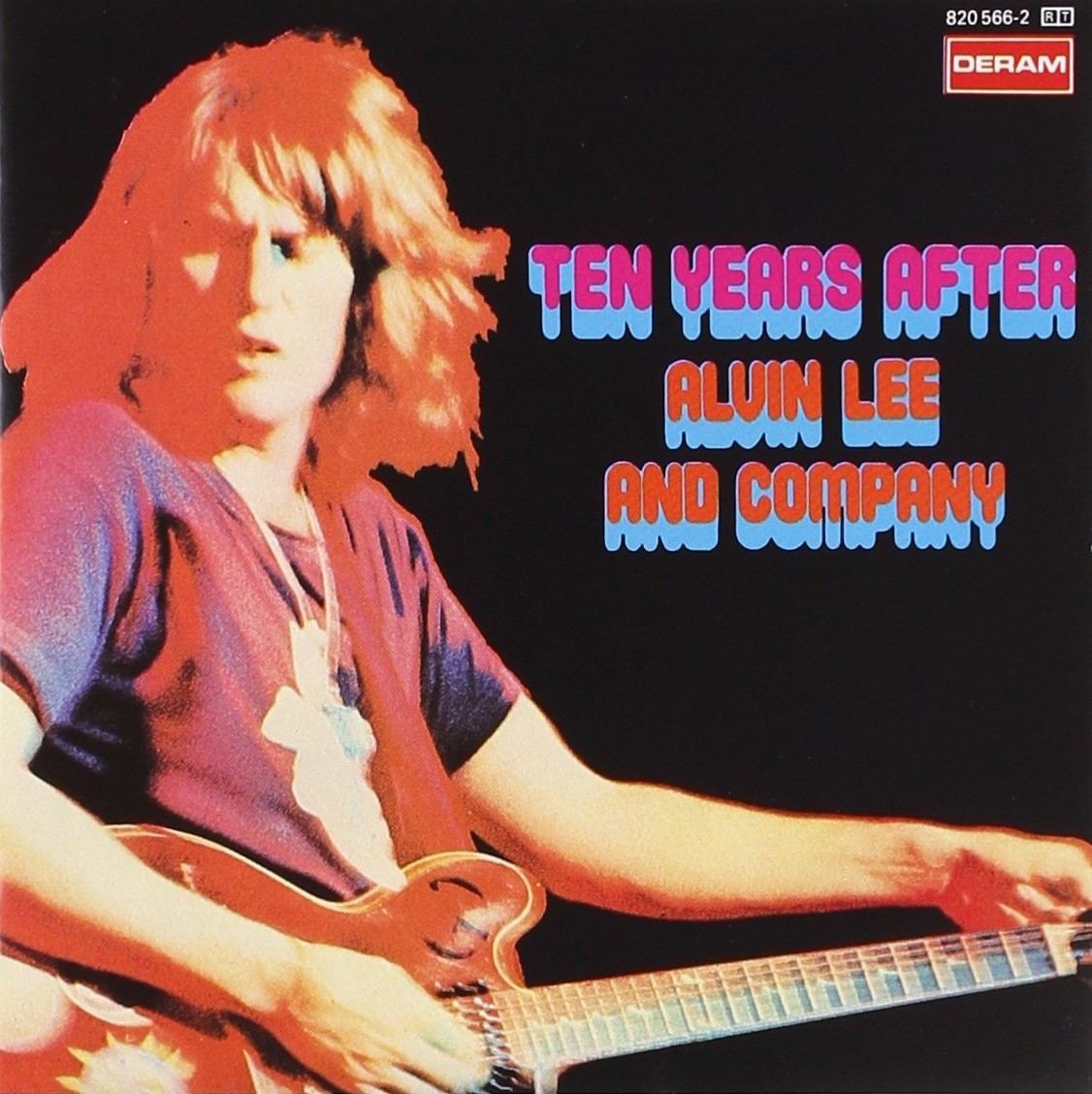

As well pursuing our band project Alvin and I started playing sessions together and separately. I don’t recall all the records and radio broadcasts I’ve played on. Often I’d play on a backing track and never meet the artiste. We also worked as a backing band for many pop stars of the day: Eden Kane, Ricky Valance, Nelson Keene, Vince Eager, Dickie Pride, Lance Fortune, The Ivy League, The Flowerpot Men, The Vernon’s Girls and Johnny Gentle and many others.

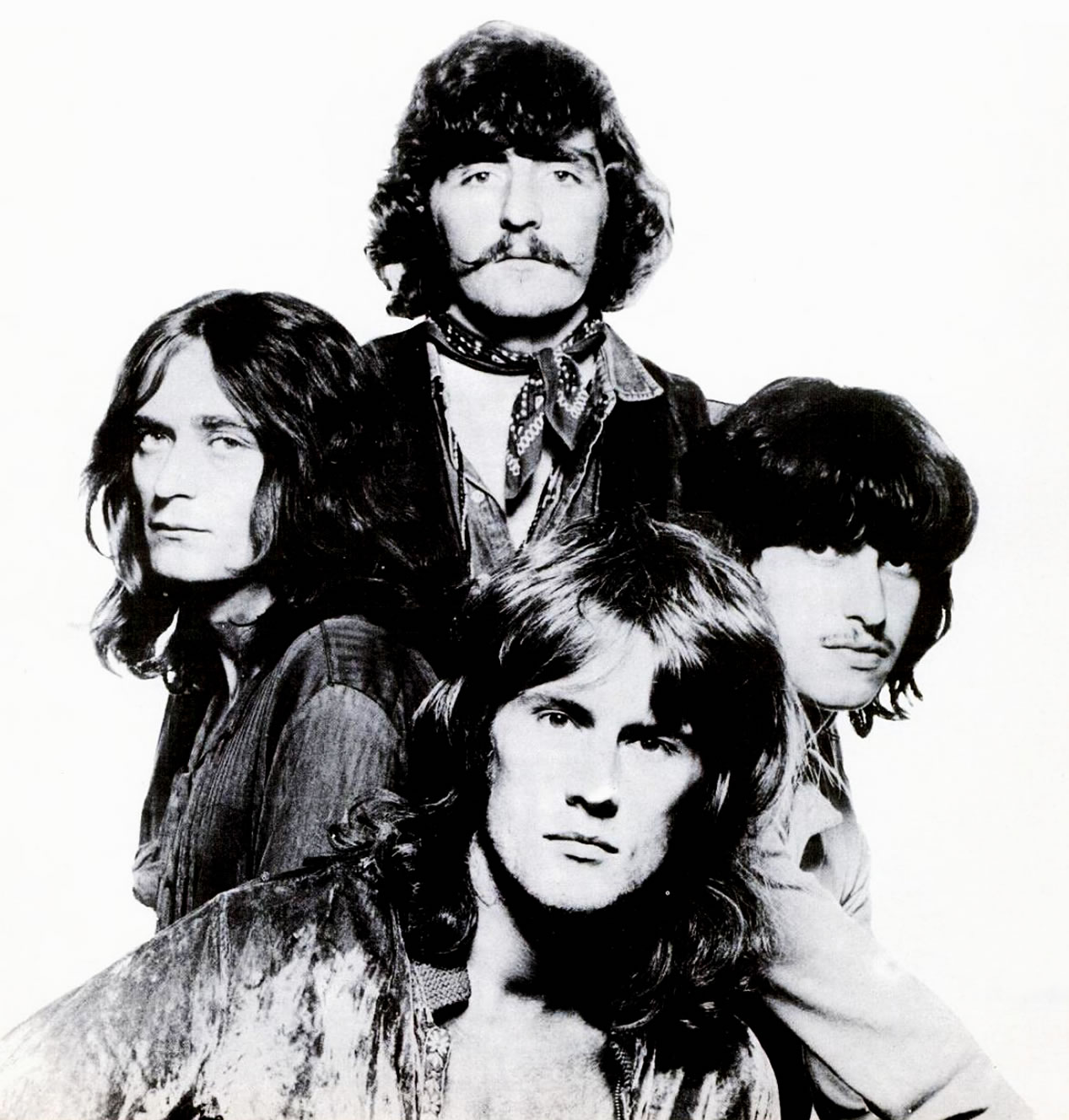

A short run as actor/ musicians in London’s West End finally gave us a foothold in the capital city. It was our third and final attempt at cracking the London music scene. This was when Ric Lee joined us as drummer. Chick Churchill was to join later.

To supplement our incomes the line up that was later to become ‘Ten Years After’ toured and recorded with pop trio ‘The Ivy League’ I continued to do session work and also took an evening job playing in a nightclub with Jazz guitarist Denny Wright.

What can you tell us about formation and joining with The Jaybirds which later became Ten Years After?

I joined ‘The Atomites’ in 1959. They intended turning professional and moving from Mansfield to London. Two weeks after joining the band the guitarist left followed by the vocalist. We advertised for a new guitarist and Alvin Lee applied for the job. Alvin introduced vocalist Ivan Jaye and I think we changed our name almost immediately to ‘The Jaycats’ and later to ‘The Jaybirds’.

The Jaycats line-up that went to London in 1960 was Alvin Lee guitar, Ivan Jaye vocals, Roy Cooper guitar, Pete Evans, drums and myself on bass.

In 1962 Ivan and Roy became disillusioned and quit. We carried on as a trio and, in between spending time in London, Alvin, Pete and I played in Germany at the famous ‘Star Club’ Hamburg. This was around the same time as ‘The Beatles’ We played for many hours every night and this was where we learned the skills without which we would not have been successful.

Drummer Pete Evans left in 1964 to be replaced by Dave Quickmire. Ric Lee replaced Dave in 1966. Chick Churchill joined the band soon after.

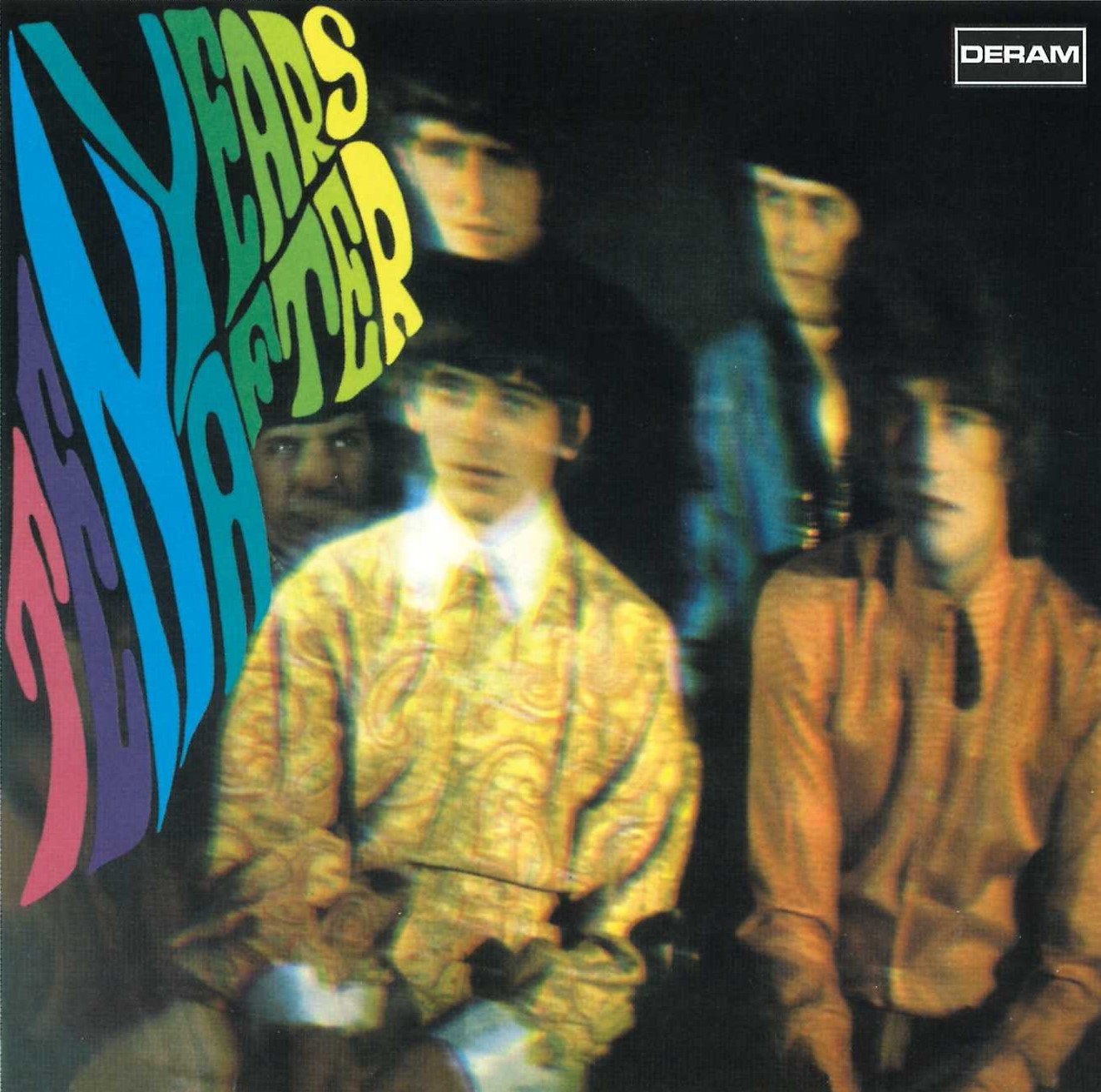

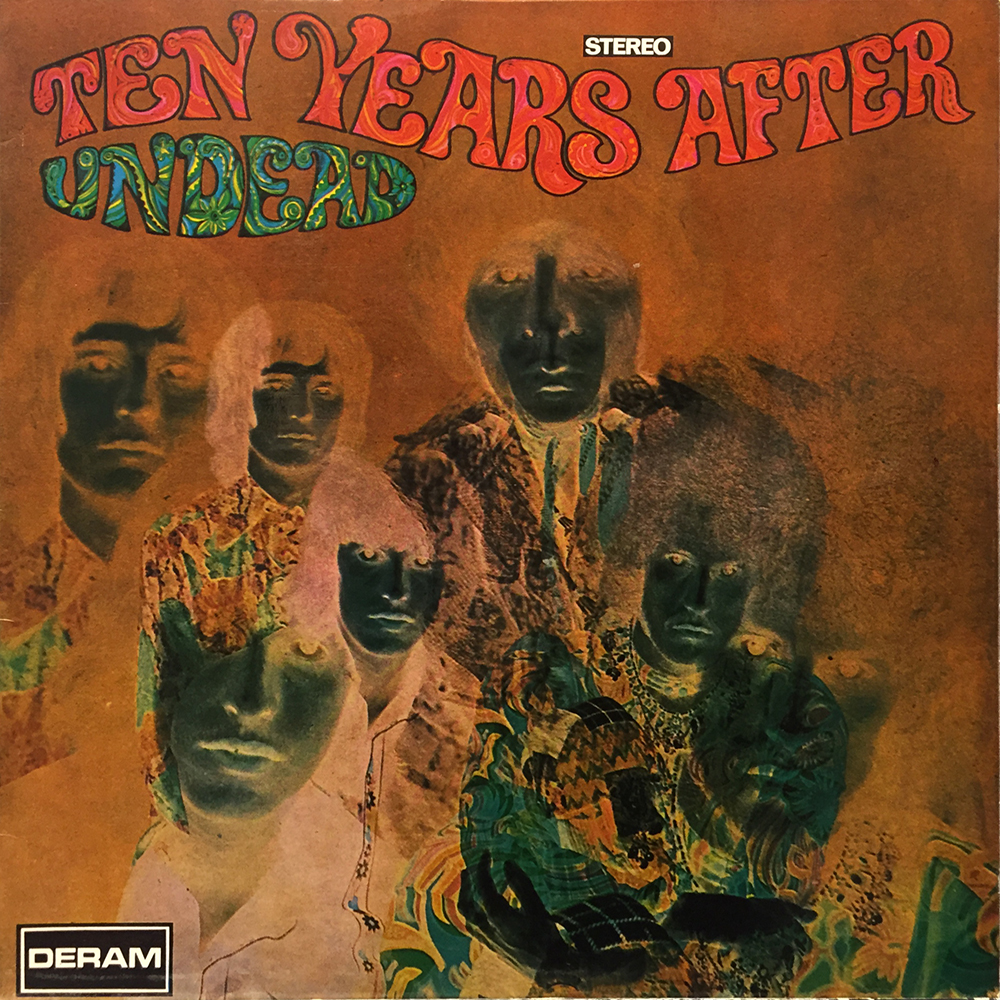

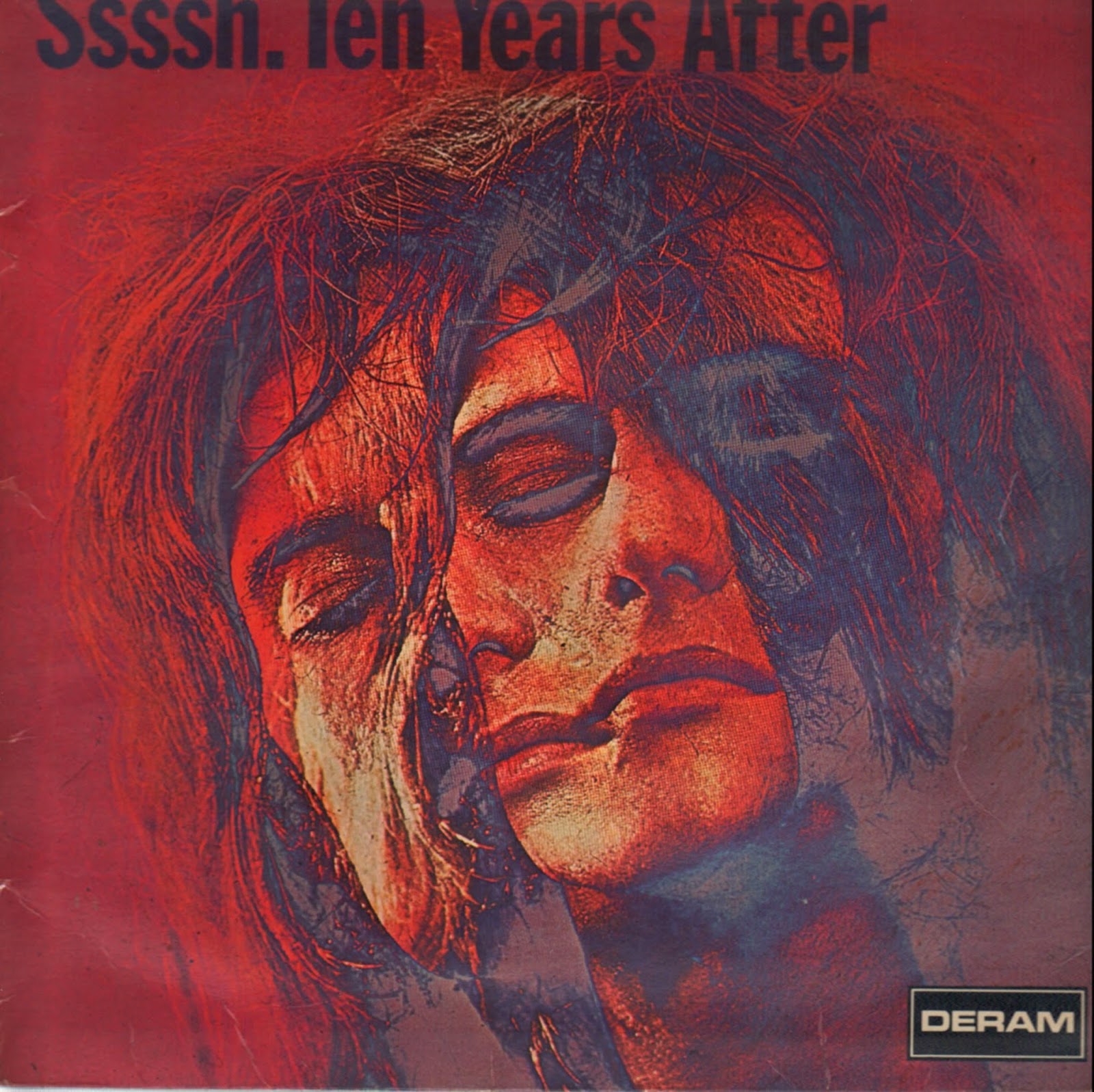

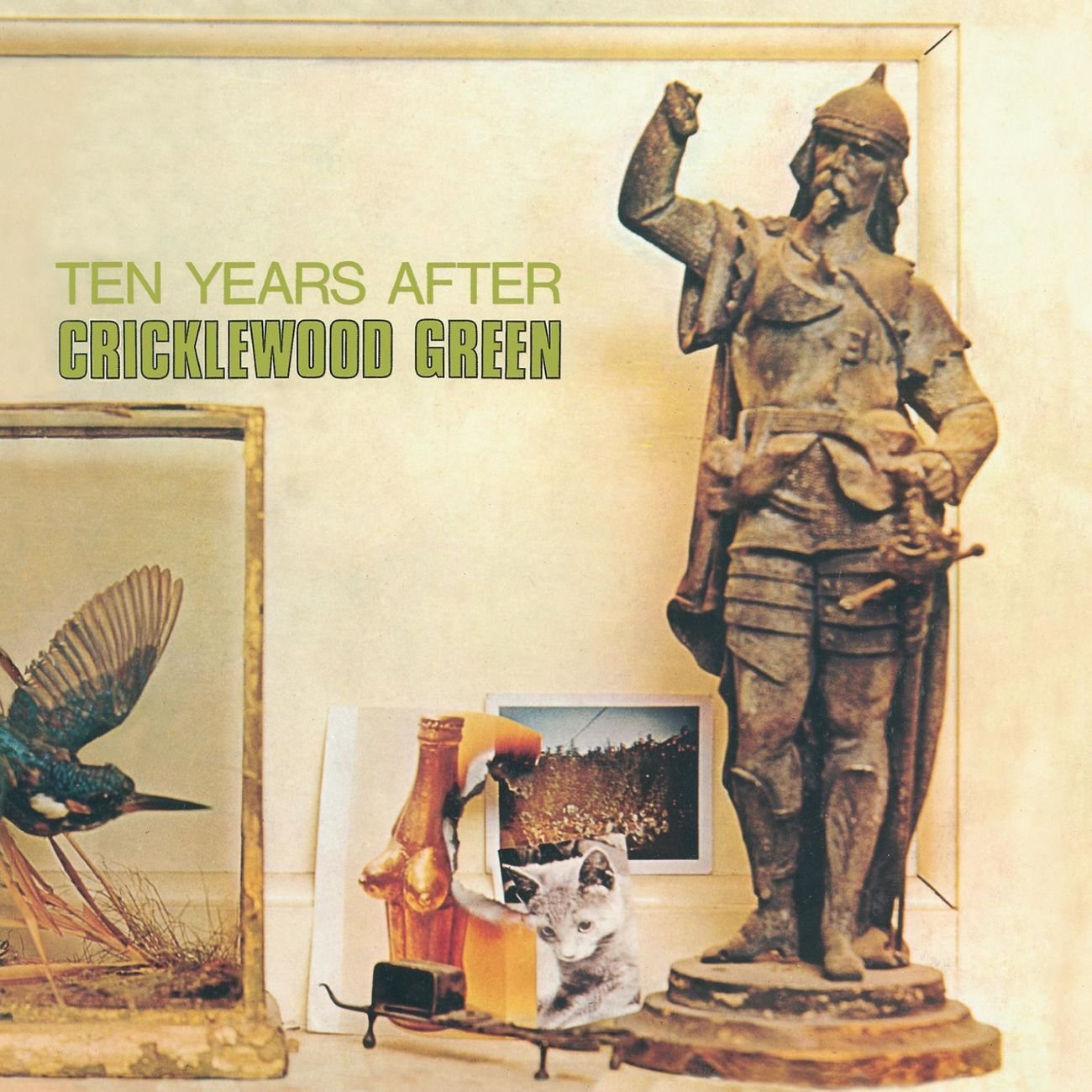

You got a contract with Deram Records and soon you released your debut album.

There had been no instant success. Alvin and I had signed a recording contract in 1960 with record producer Joe Meek but nothing was released. It took over seven years to build up a following and to have a record released under our own name. I managed the band up until just before we got the Deram recording contract so I know how hard it was to get work.

“My main contribution was adding many of the signature riffs you hear on the records.”

What are some of the strongest memories from being in studio for the first time making your debut album?

We had auditioned for Decca about a year earlier in the very same studio and were turned down. The engineer on our debut record was Gus Dudgeon the same engineer as on our failed audition.

It was the realization of a dream to be making a record as ‘Ten Years After’ and with the help of producer Mike Vernon we set out to record the songs we’d been playing live. The whole process, tracked on four-track tape and mixed down to two tracks was finished in about half dozen three-hour sessions.

Decca Studios was very corporate and business-like in the mid-sixties. There were regular tea breaks and a trolley lady would visit the studio with a refreshments. I recall it was the first time I’d been allowed into the control room. Usually musicians listened to playbacks on a remote studio speaker. In between the recording dates we continued to play gigs around the UK.

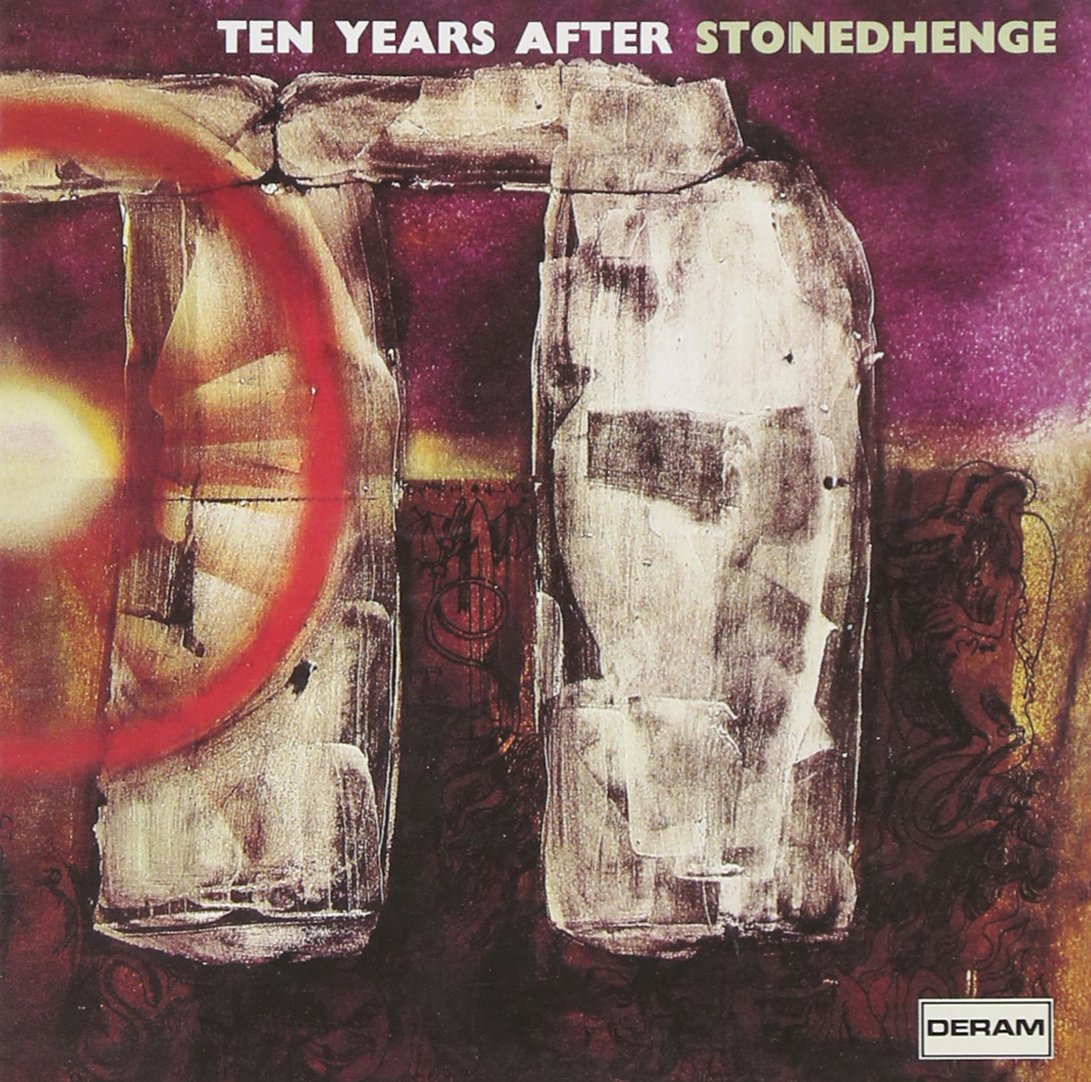

How about ‘Stonedhenge’? How did you like it?

I guess I liked it at the time but listening to the album fifty years later it’s certainly very strange. The band was experimenting. Stereo records had just begun to appear on the scene and we tried to do something different. I think the best song was ‘Hear Me Calling’

‘Stonedhenge’ is probably best listened to stoned.

What was the song writing process in the band?

Alvin was not open to co-writes. Usually he played us work tapes and we’d jam something out in the studio. My main contribution was adding many of the signature riffs you hear on the records. As time went by I considered asking for a writing credit but the other guys told me not to rock the boat.

Chrysalis offered you a new contact and you recorded ‘A Space in Time’.

We’d played Woodstock and already headlined a number of sold out arena tours. The Rock and Roll circus was travelling at a very fast pace all over the world. So fast in fact that Alvin asked to take a year out from touring to allow time for things to cool down. It was too much stress for him. He thought we were too big and asked our manager to “De-escalate us”.

Believe it or not, as crazy as it sounds, that’s exactly what we did. We retired to our respective country mansions and took a sabbatical.

Our recording contract with the Deram label had come to an end and we were offered substantial record deals from several major labels. Clive Davis signed us directly to Columbia Records for North America. Our manager Chris Wright retained the ‘Rest Of The World’ rights for his own production company Chrysalis Records.

The first album released on the new label deal was the aptly titled ‘A Space In Time’. The time off from touring had given Alvin the opportunity to come up with one of the best songs I think he’s ever written. ‘I’d Love To Change The World’.

Three more albums followed in the seventies and then you decided to stop.

The band had been on tour constantly since the mid sixties. Relationships were a little fraught. We’d grown tired of living in each other’s pockets. It was like being married to three people at the same time.

All of us had other things going on in our lives but instead of sitting down and working out a compromise solution that suited suit everyone we threw away all we’d worked so hard for and parted company. It beggars belief that people can be so stupid.

You toured the whole world and appeared on many worldwide known music festivals, including Woodstock. What are some of your favourite memories?

The movie of the same name assured Woodstock and Ten Years After a place in history but for me it was just one festival of many that we played. I loved the whole period and enjoyed every gig. Headlining a major venue like, for instance, ‘Madison Square Gardens’ NYC or ‘The Albert Hall’ London for the first time was a big thrill. I consider myself very lucky to been at many of the places where musical history was made. I sometimes feel like the Forrest Gump of rock.

You always had a passion for the recording process and you produced records for UFO, Magnum, Waysted, Procol Harem, Frankie Miller, Richard and Linda Thompson, Brigitte St John, John Martin, Kevin Coyne, Sassafras, Motorhead, Hatfield and The North, The Bogie Boys, The Winkies, Chris Farlowe, Chevy and many more. What do you enjoy the most from working in the studio with other musicians?

I enjoy the whole recording process as producer or player although sometimes it’s tricky to do both at the same time.

I’m comfortable in the studio and as a producer I enjoy helping an artiste interpret their music in that environment. When a great song and performance come together the studio is a magical place.

As a bass player working with different players makes me look at things in different ways. It takes me out of my musical comfort zone and we all need that if we want to develop our skills.

Around 2003 Ten Years After started playing again with a different line-up. How was playing with Gooch instead of Alvin Lee?

Of course it was different playing with Joe instead of Alvin and at first many TYA fans did not like the idea of but when they heard Joe play most changed their minds. We were lucky to have found him.

Joe interprets the songs in his own way and did not copy Alvin’s playing aside from the signature licks. The key to TYA’s style of music has always been the interplay between bass and guitar that remained the same.

You recorded a few albums. How are you satisfied with those albums?

I’m not completely satisfied with any record I’ve worked on. I feel things can always be done better but a decision has to be made or nothing ever gets finished.

So I do the very best I can with what I have to work with at the time and move on. I’ve always found it difficult to listen to any record once it’s finished.

Some time ago you decided to leave the group. Can you explain the circumstance behind this decision?

It was a sad moment for me. I will always love the music of TYA but the band had become a dictatorship with no room for compromise. The tail was wagging the dog and I was angry with myself for allowing it to happen. I found myself in a non-creative negative working environment. I was very unhappy and it was making me ill.

Alvin Lee’s death was a wakeup call for me to question what I wanted to do for the rest of my musical life. I had no option but to leave the band and in doing so give up all rights to TYA name.

What currently occupies your life?

I don’t want to waste one day of the time I have left. I intend spending more time with my family but I have no plans to retire. Music is what keeps me going and I will always be looking for new musical horizons -playing, writing or recording.

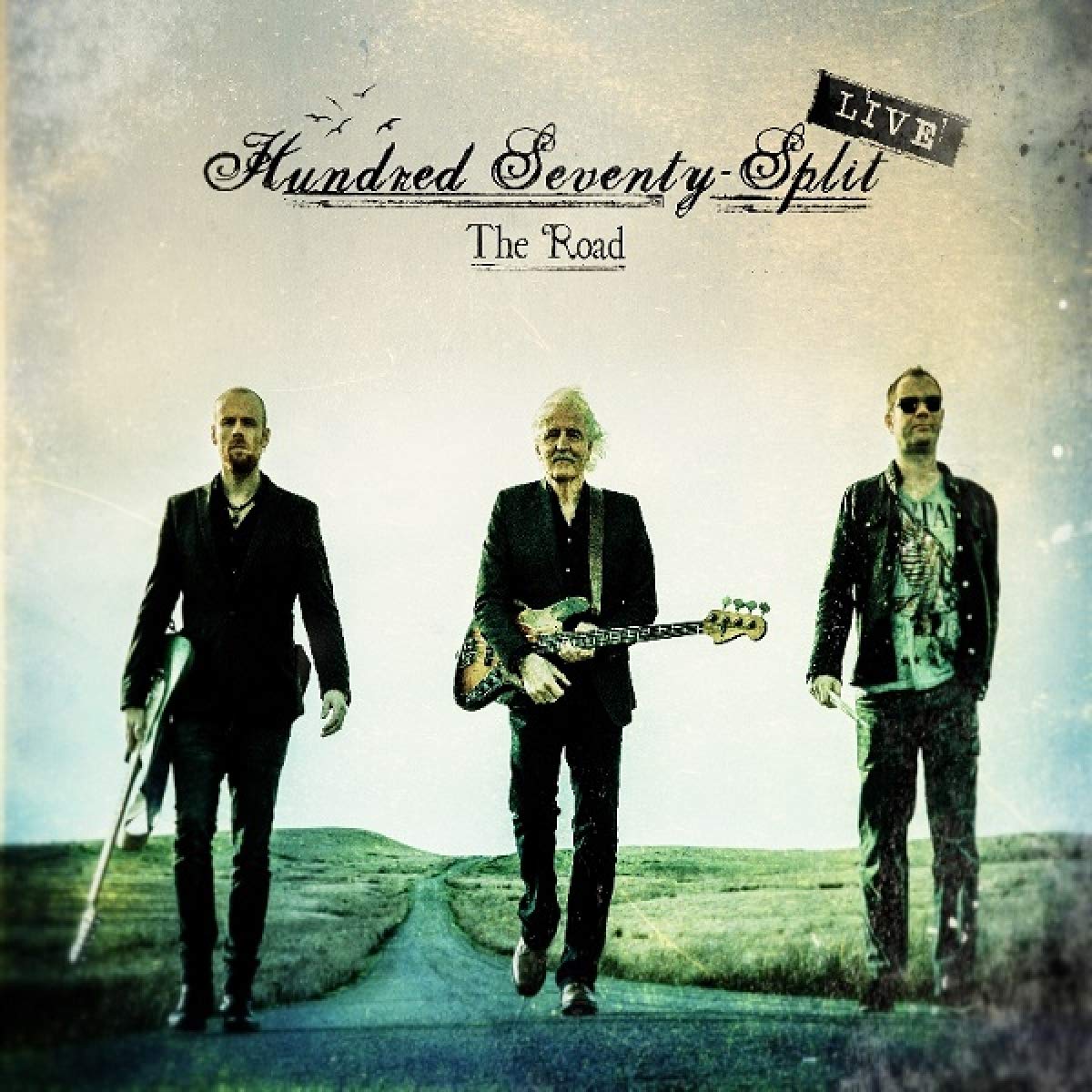

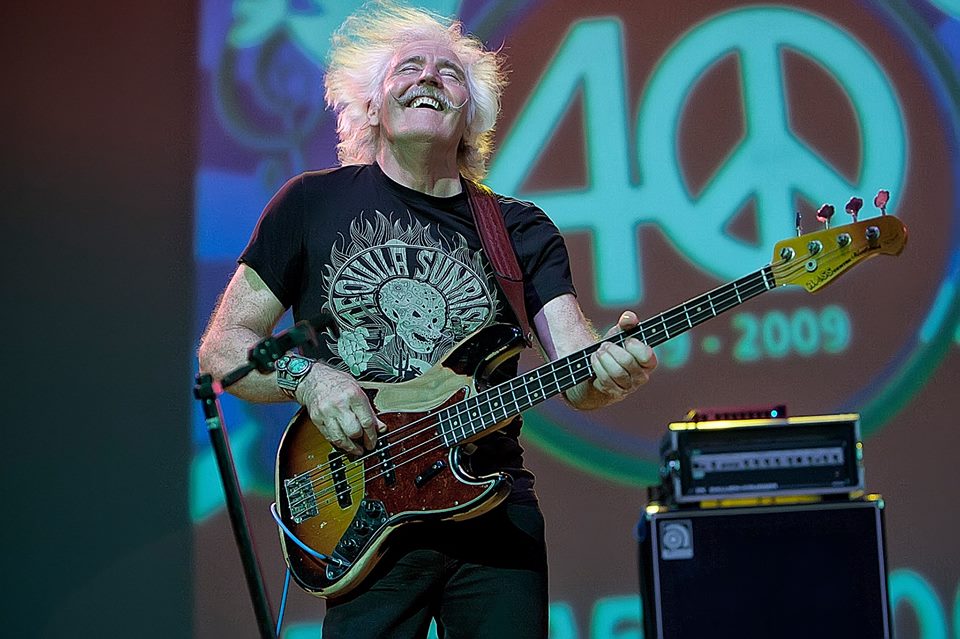

I am still playing with Joe Gooch and drummer Damon Sawyer in the band ‘Hundred Seventy Split’. It’s been like starting all over again without the advantage of a ‘Heritage name’ and we’ve had to prove ourselves these past few years. However it seems that our fans approve of our music and we’re currently in the middle of recording our fourth CD.

Thank you for taking your time. Would you like to send a message to It’s Psychedelic Baby readers?

If you’re reading the magazine I guess you’re interested in the kind of music featured in it. I’d like to thank you for supporting the genre in general and for giving musicians like me the opportunity to continue to do the job we love. Leo Lyons

Klemen Breznikar

Leo Lyons Official Website

Hundred Seventy Split Official Website

Great interview! -thanks Leo for still rockin' us, and thanks for all the great music you've given us over the years too. -peace 🙂

Thanks Leo, interesting interview

Leo is one of the nicest guys you will ever meet and can still out rock those half his age! 100/70 Split is well worth a listen.