Steve Katz interview | The Blues Project, Blood, Sweat & Tears and American Flyer

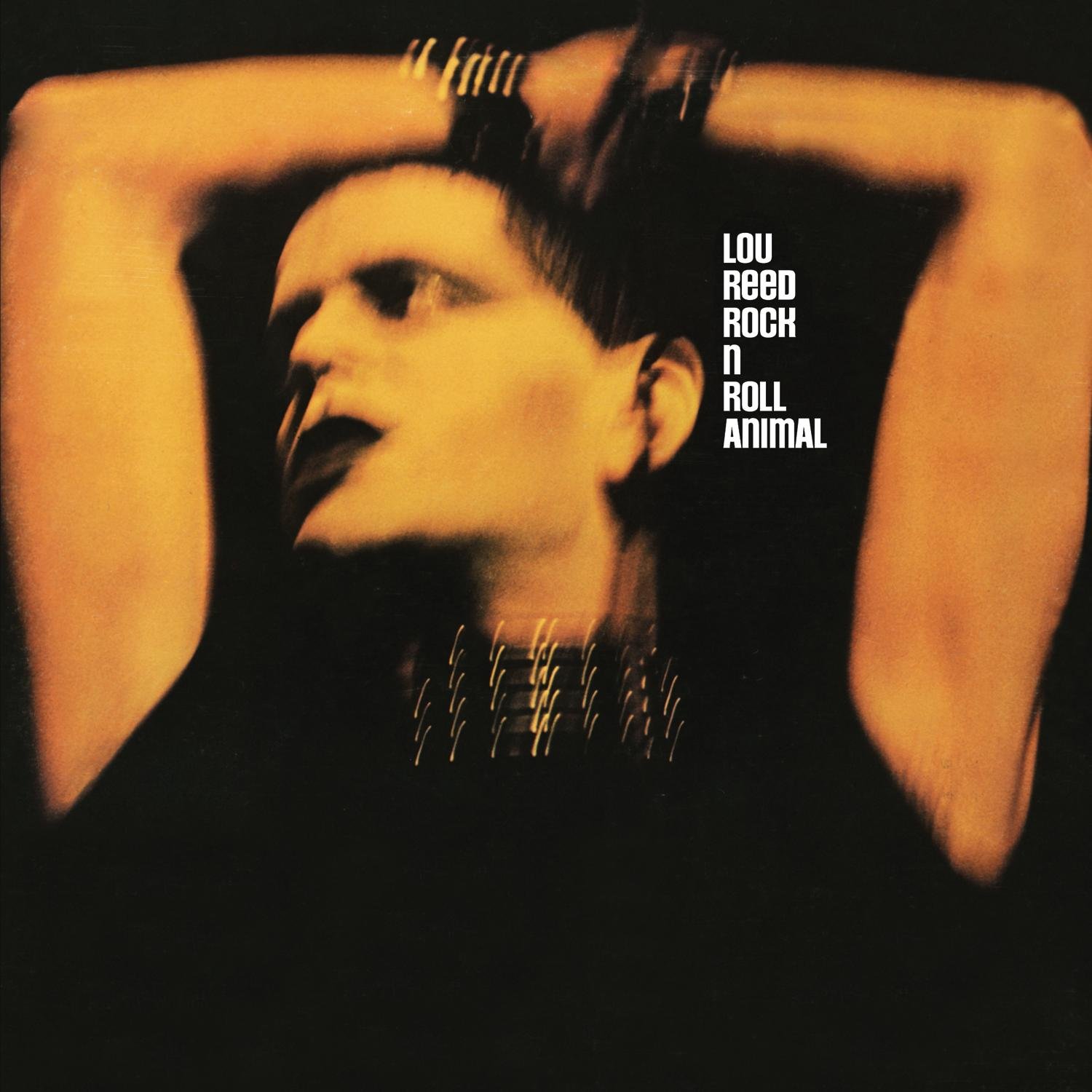

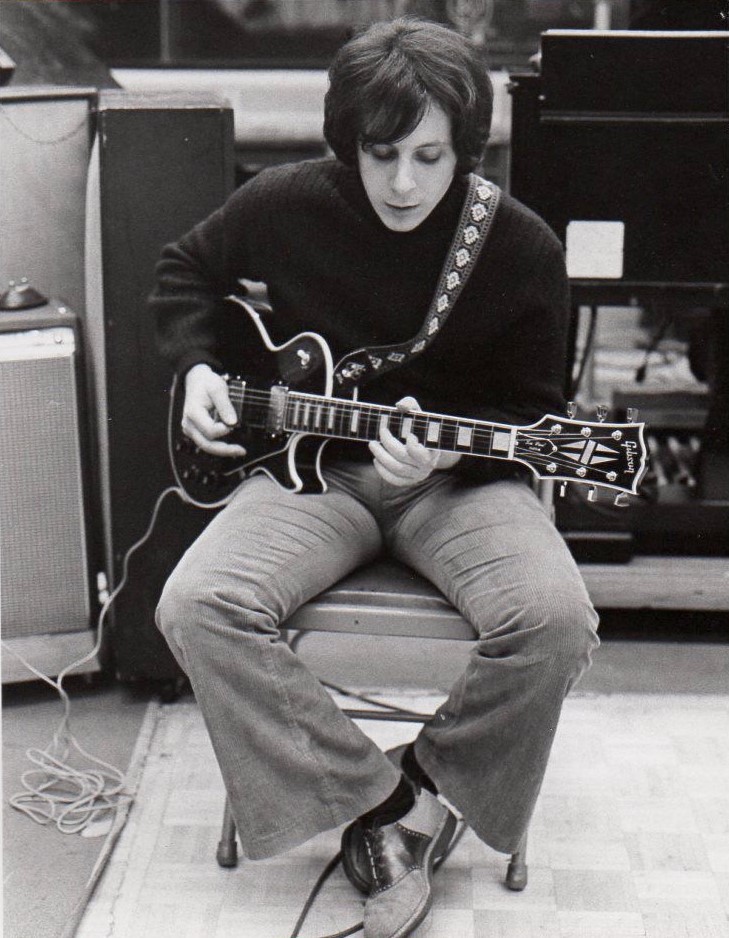

Steve Katz is a well known guitarist, singer, and record producer. Through his prolific career he has been essential part in bands like The Blues Project, Blood, Sweat & Tears and American Flyer. As a producer, his credits include the 1979 album ‘Short Stories Tall Tales’ for the Irish band Horslips, and the Lou Reed albums ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Animal’ and ‘Sally Can’t Dance’ and the Elliott Murphy album ‘Night Lights’. In the following interview we discussed many projects and collaborations.

“I shook hands with Otis Redding, stood on the side of the stage when Janis Joplin sang “Ball and Chain”, and had dinner with Jimi Hendrix.”

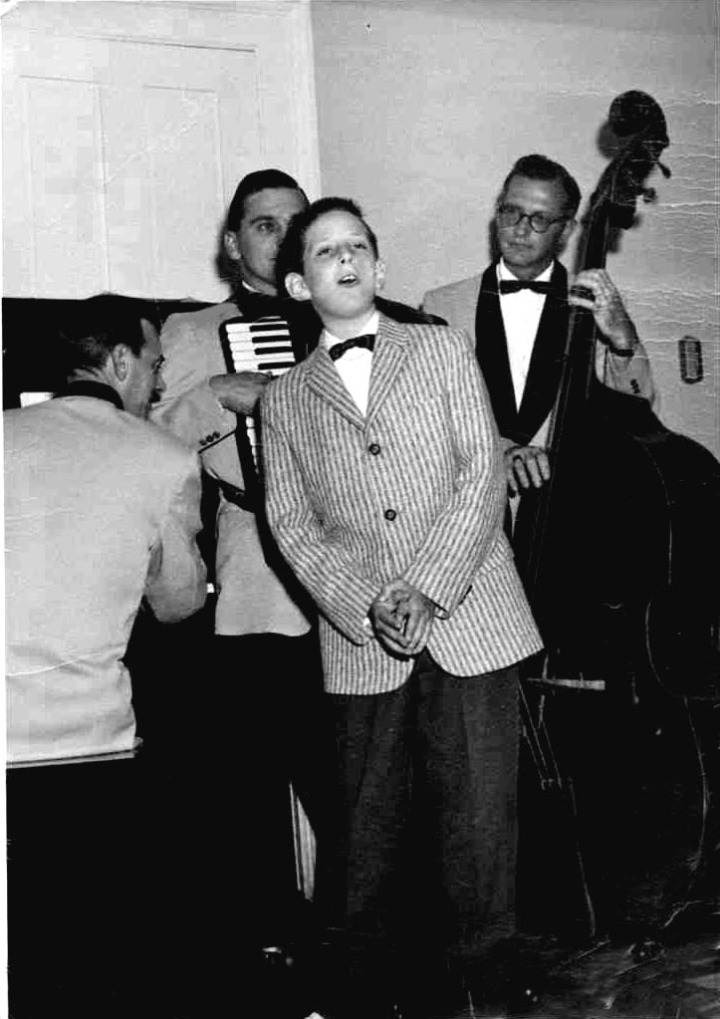

You started your career on a local TV program called Teenage Barn. Was music a big part of your family life? When did you begin playing music?

I was the only music person in our family. I collected records at a very early age and tried to sing the hit songs of the day – popular songs of the 50’s. Sometimes I would even sing out in the street when I was no more than five or six years old. People would throw change at me – some things never change. I continued to sing into my teens and auditioned for Teenage Barn in Schenectady, New York, where we lived. I won the audition and became a regular until one day when I couldn’t memorize the lyrics to a song they had chosen for me to sing. It was live TV and I kept looking down at my cheat sheet, but the cheat sheet was single-spaced and I couldn’t find my place fast enough. The show was supposed to end at 8:30, but that night it ended at 8:33, thanks to me. I was fired that night.

At 15 you studied guitar with Dave Van Ronk and Reverend Gary Davis. How did that come about?

I began to listen to a lot of authentic blues and old timey music on records and fell in love with what’s now called “roots” music. I started to go down to Greenwich Village and would wind up hanging out at the Gaslight Cafe on MacDougal Street. Dave Van Ronk hosted most of the hootenannies there. I didn’t want to just sing anymore; I wanted to be able to accompany myself and learn how to play blues. I asked Dave if he gave lessons and he said yes, so I wound up taking lesson from Dave for over two years. It was through Stefan Grossman that I wound up taking some lessons from Reverend Davis. I would drive the Reverend around to gigs as well and learned a lot from him on the road.

How did you get in touch with guitarist Stefan Grossman?

On Sundays, early sixties, I would sometimes hang out at Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village where the Sunday afternoon hootenannies would take place. One day I heard Reverend Davis playing guitar by the fountain. I had yet to meet him, but I was surprised to find him there. I went over to where he was playing and saw that that it wasn’t Reverend Davis at all, but an uncanny copy. It was Stefan Grossman. That day, Stefan and I became lifelong friends.

With Stefan Grossman you occasionally worked as road managers for Reverend Gary Davis and met many amazing musicians including Son House, Skip James and Mississippi John Hurt. What kind of impact had that on you later in your career and what are some of the highlights from meeting Blues Giants?

I met Son House, Skip James, and Mississippi John Hurt when Dick Waterman and Tom Hoskins booked them into the Gaslight after “rediscovering” them. I got close with Mississippi John Hurt later in 1964 in Los Angeles when Stefan, Ry Cooder, and myself played as a group called The Gramercy Park Sheiks at the Ash Grove. We became roommates for about a week, John, myself, and Stefan. John Hurt was one of the most beautiful people I’ve ever met. He became my surrogate father that week.

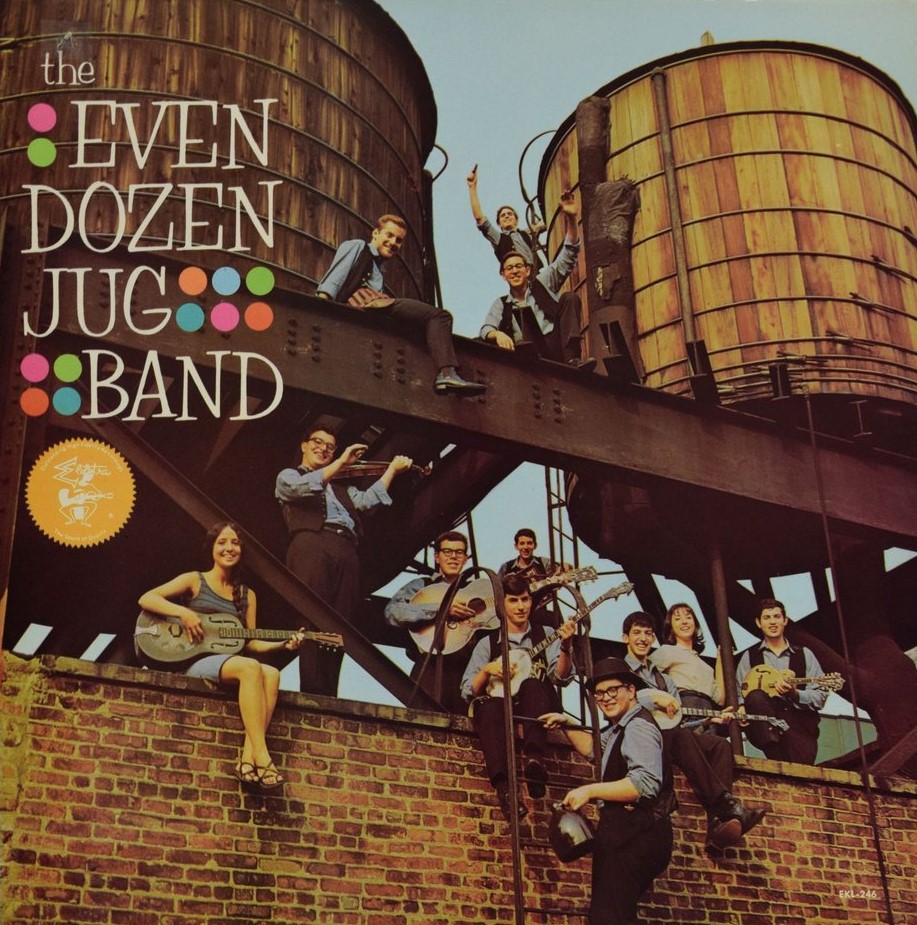

How do you remember Greenwich Village in the sixties and The Even Dozen Jug Band?

It was post-Beatnik, pre-hippie times – early sixties. The folk clubs were The Gaslight Cafe and Gerde’s Folk City. The main jazz clubs were the Village Gate and the Village Vanguard. There was amazing music happening every night somewhere in the Village and all over Manhattan. I was part of the blues crowd of young musicians. There was also the bluegrass/old time crowd. We all wanted to jam together and so we chose jug band music as a common denominator – so we started a jug band. There were too many guitar players, so I quickly learned how to play washboard and sang some of the leads. The band included some great musicians – David Grisman, Stefan, John Sebastian, Josh Rifkin, and Maria Muldaur to name a few. We recorded one album for Elektra, played a Carnegie Hall folk festival, played on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson (Johnny sat in on kazoo), broke up and went back to school.

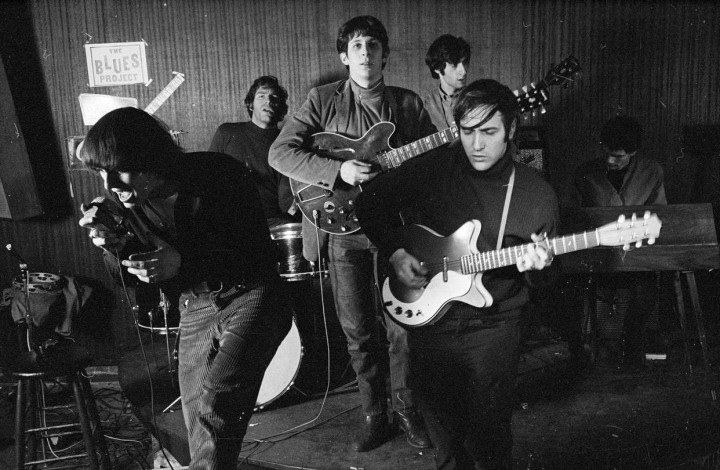

Can you elaborate on the formation of The Blues Project?

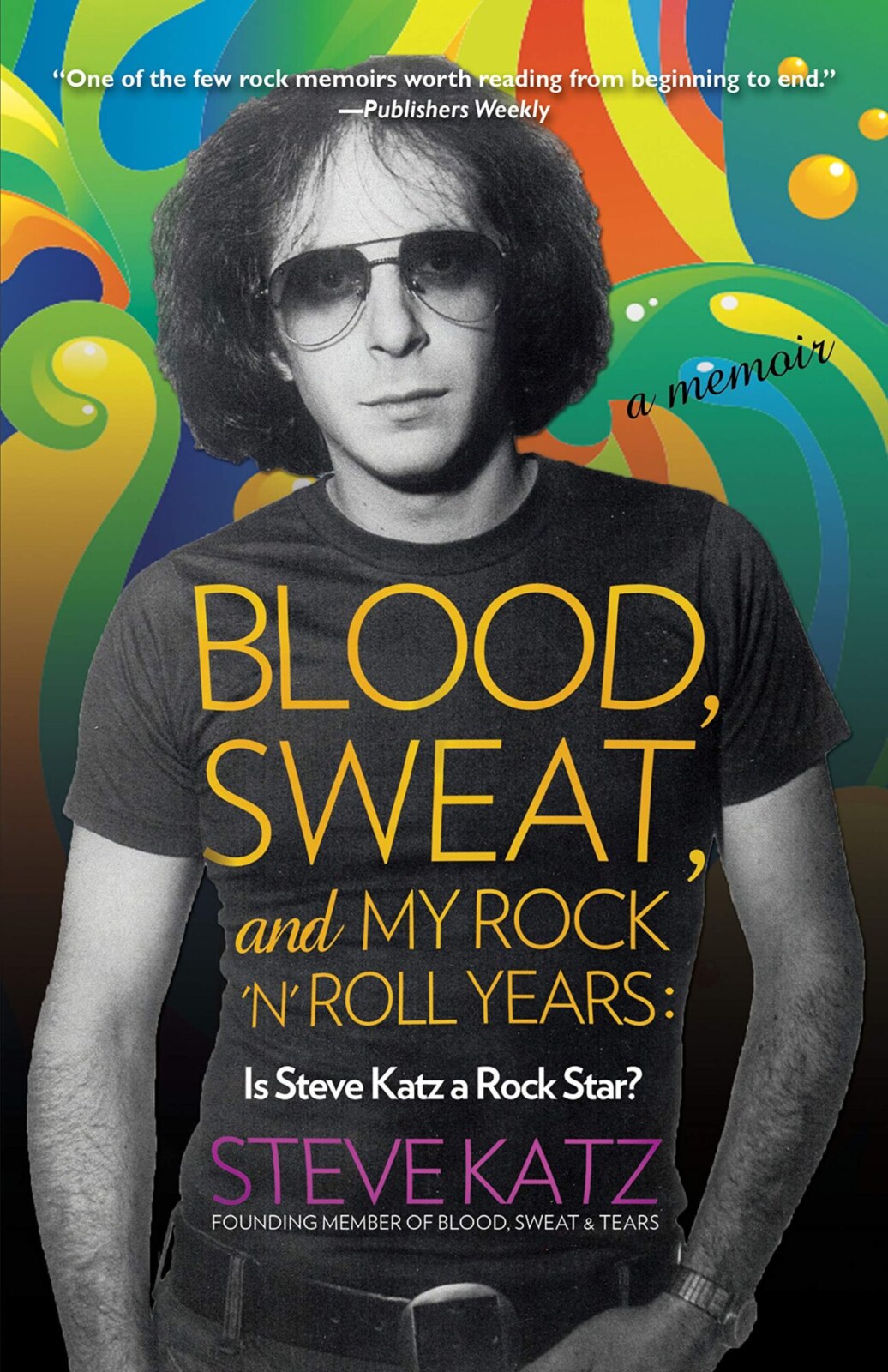

After the break-up of the jug band, Stefan and I took a trip to Berkeley and LA. When we returned, I went back to school and taught acoustic guitar at Fretted Instruments in Greenwich Village on the weekends. This was the autumn of 1965. The Villagewas making the transition from Beatnik old Italian neighborhood to the counter-culture. Bob Dylan played The Newport Folk Festival with electric instruments and most of my “folkie” friends went uptown to buy electric guitars. One of those friends was Danny Kalb who had started an electric blues band. He needed a rhythm guitarist and so he came up to Fretted Instruments and asked if I’d be interested. I said I never played electric guitar and… (you can read much more in “Blood, Sweat, and My Rock ‘n’ Roll Years: Is Steve Katz a Rock Star?“).

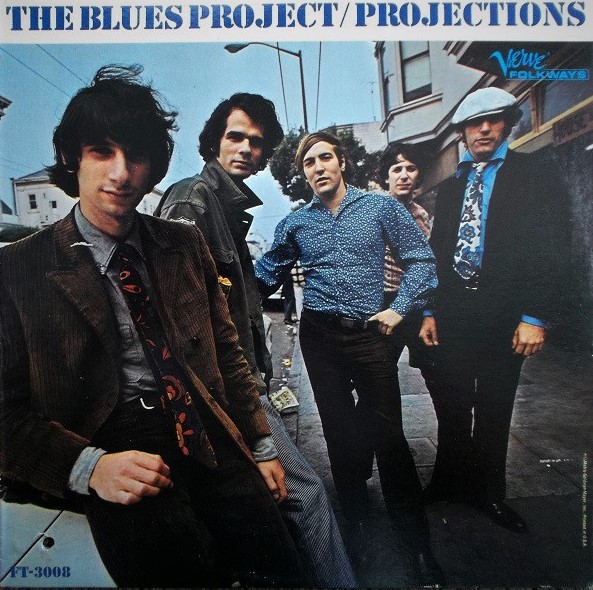

What are some of the strongest memories from recording Projections?

1) We had 5 minutes left to our session, but our producer, Tom Wilson, wouldn’t let me redo a vocal on my song – Eric Burdon was waiting outside for his session and Tom didn’t want to hold him up. 2) Danny’s string loosened in middle of “Two Trains Running”. Did we get to do it again? Of course not. You can hear it on the album. 3) Our LA sessions were produced by Billy James and Jack Nietzsche. When I came to the studio one day, our manager was sitting in the producer’s chair and Jack was sitting on his own attache case. Needless to say, the manager didn’t last very long after that.

Would you share your insight on “Steve’s Song”? What’s the story about it?

“Steve’s Song” was original titled “September 5”, but, thanks to our idiot manager and the people in the art department at MGM, they didn’t have the correct title so they just changed it themselves. The first time I saw this in the credits, it was too late to change it back to my original title. It was the first song I had ever written.

“The Cafe Au Go Go gigs were, of course, amazing.”

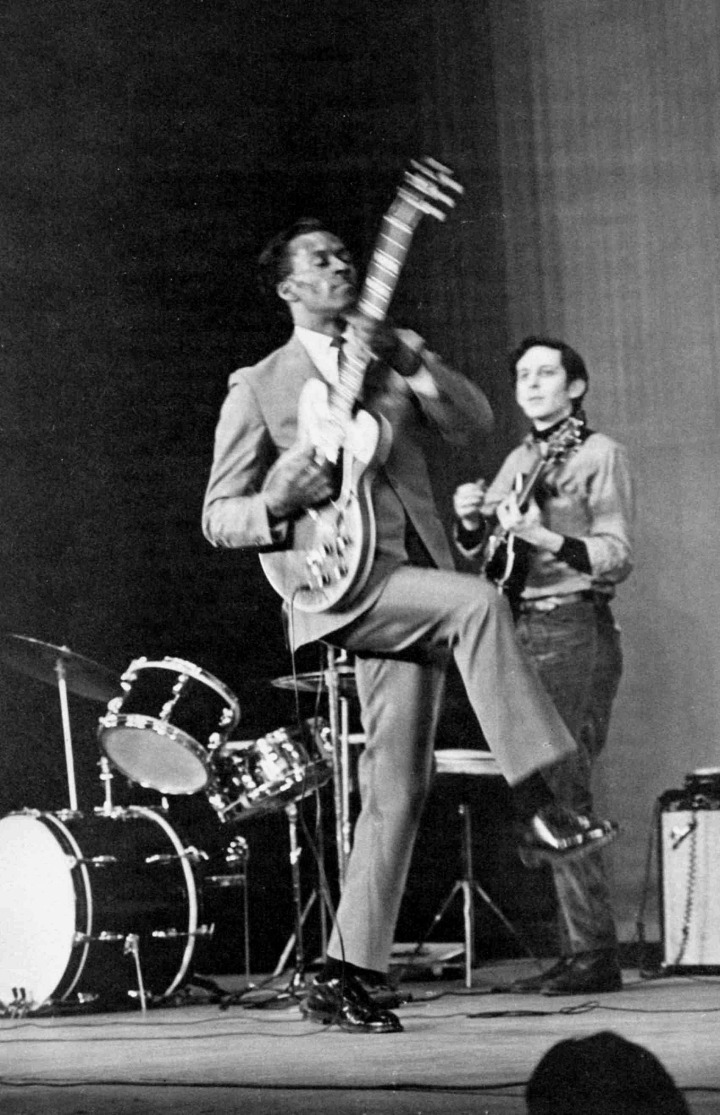

You probably had the most fun with The Blues Project playing live as house band at the Cafe Au Go Go. What was the highlight of your time in the band? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

The Cafe Au Go Go gigs were, of course, amazing. The jams were incredible. Some of the biggest names in Rock at the time participated – From B.B. King to The Grateful Dead, it was non-stop fun. And the funny thing, in retrospect, the Cafe Au Go Go didn’t serve liquor. But the audiences always went crazy. For a while, next door at The Garrick Theater, Frank Zappa and The Mothers had a long run. In between our shows I would run next door and catch the Zappa show. Just astounding. Speaking of which, one of the most memorable gigs of the many memorable gigs was with The Mothers and Canned Heat at the Fillmore in San Francisco. I came down with pneumonia but still played one of the nights. At the end of our set, I had to be carried off the stage.

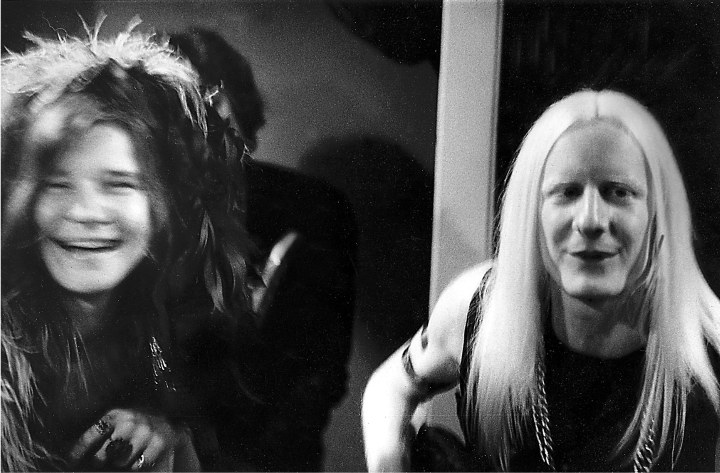

Your last major gig was Monterey Pop Festival. You can’t beat that, can you?

No, you can’t. I shook hands with Otis Redding, stood on the side of the stage when Janis Joplin sang “Ball and Chain”, and had dinner with Jimi Hendrix. OK, it was at the hot dog stand backstage, but how many people can say they shared a bag of potato chips with Jimi Hendrix? The only bad thing was that our keyboard player’s organ and vocal mic weren’t working.

What can you tell us about the formation of Blood, Sweat & Tears? What’s the story behind Child is Father to the Man album release?

Al Kooper left the Blues Project just before we were booked at Monterey. Things were falling apart by then within the band and so I was trying to figure out what I was going to do when I got a call from Al who wanted to start his career over in London. Problem was, Al didn’t really have the funds to get over to England, so we decided to start a band. Al always had this concept of having a horn band, so we hired a 4 piece horn section who just happened to be some of the best players in New York. It sounded so good that the guys in the horn section wanted to be part of the band instead of getting a salary. So we said “fine, you can starve like the rest of us”. We rehearsed at The Cafe Au Go Go and played our first gig there, opening for Moby Grape. Elektra Records wanted to sign us for what today would be a paltry fee, but Columbia Records said they would match the offer and throw in some Fender amps. We went with Columbia and did our first album, Child is Father to the Man in two weeks.

“I could earn royalties from unrequited love affairs.”

What was the writing and arranging process like?

I started writing when I was in the Blues Project. I loved to experiment with open tunings and so my first song, “Steve’s Song” was written in G-tuning. My best songs were written when women walked out on me. It became a tradition and continued when I realized that I could earn royalties from unrequited love affairs. The arrangements were pretty much a group thing in the Blues Project. In BS&T, Fred Lipsius, Dick Halligan, and Al, did most of the arranging. I did “Meagan’s Gypsy Eyes” with Freddy, which sort of came out like the theme from The Dating Game.

You were part of all the major Blood, Sweat & Tears releases. What was it like to be part of the band and how did the band evolve album after album?

The first band was fun. We never expected hit records and never got any. The second album changed all that. As soon as we had our first hit we were confronted by a barrage of lawyers, accountants, managers, etc. It was mainly corporate. We toured our asses off and hardly received any compensation for our work on the road. Thank God for royalties. The Blues Project was different. It was like a brotherhood – we both hated and loved each other. BS&T didn’t feel like that. We were too beleaguered by the music business. It was more fun when we were paying dues. As each album was released, the band was going in a jazz direction that I didn’t feel comfortable with, so after six years and with an offer to produce Lou Reed, I decided to leave BS&T and get back to rock’n roll.

“I played the entire set thinking that I was upside down.”

Where and when was your most memorable gig?

It was in Las Vegas, at the Convention Center. Our opening act was a band from Berkeley called The Joy of Cooking. I knew a couple of the women in the band and went to their dressing room to say hello before we went on. I was sitting with the band when someone passed around a joint. After taking a couple of hits, the drummer said to me “Do you know what you’re smoking?”. I told him that I assumed it was just grass and since I was going on stage in ten minutes, please tell me if it wasn’t. He said I just smoked some TCP. And so I played the entire set thinking that I was upside down. You can’t get much more memorable than that.

How did you first get in touch with the production process?

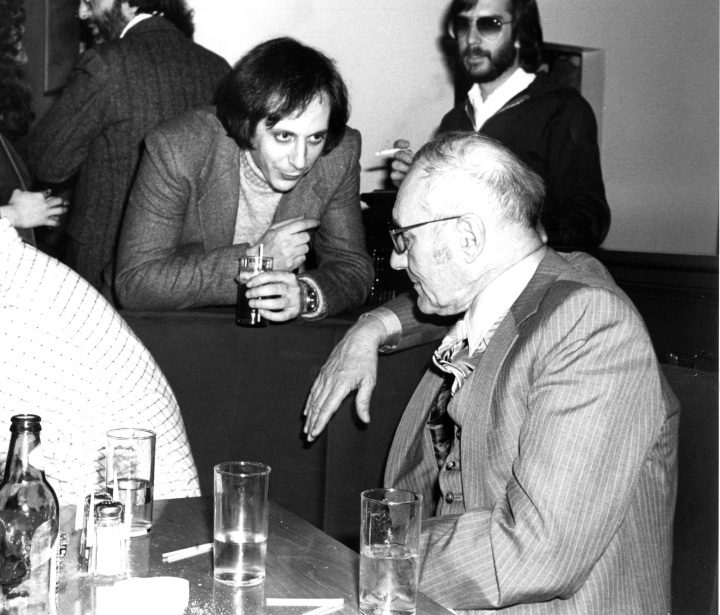

Of course you always learn as a musician in the studio, but I really learned when I worked with Lou Reed on Rock’n Roll Animal. As a producer, you have to work with budgets and make both the artist and the record company happy. You have to deal with a lot of egos and learn the technical aspects as well. It took a couple of years for me to feel comfortable as a producer. You had to be a psychiatrist, arranger, accountant, techie, etc. It’s a huge job.

One of your first well known records you produced is Rock & Roll Animal and Sally Can’t Dance for Lou Reed. How did that come about?

Rock & Roll Animal was my first project after leaving BS&T. Lou was rehearsing in the same space we were and he and I became friendly. He had just come off of Berlin, a gorgeous album that was a commercial failure. Lou asked my advice as to what he should do next and I said that if I were him I’d get a great rock band together and re-do some Velvet Underground songs and do it soon, probably as a live album. So he asked me to produce it. Sally Can’t Dance was a lot harder to do. Lou’s drug intake was taking its toll and making it very difficult to work with him. On top of that, my house burned to the ground just before mixing.

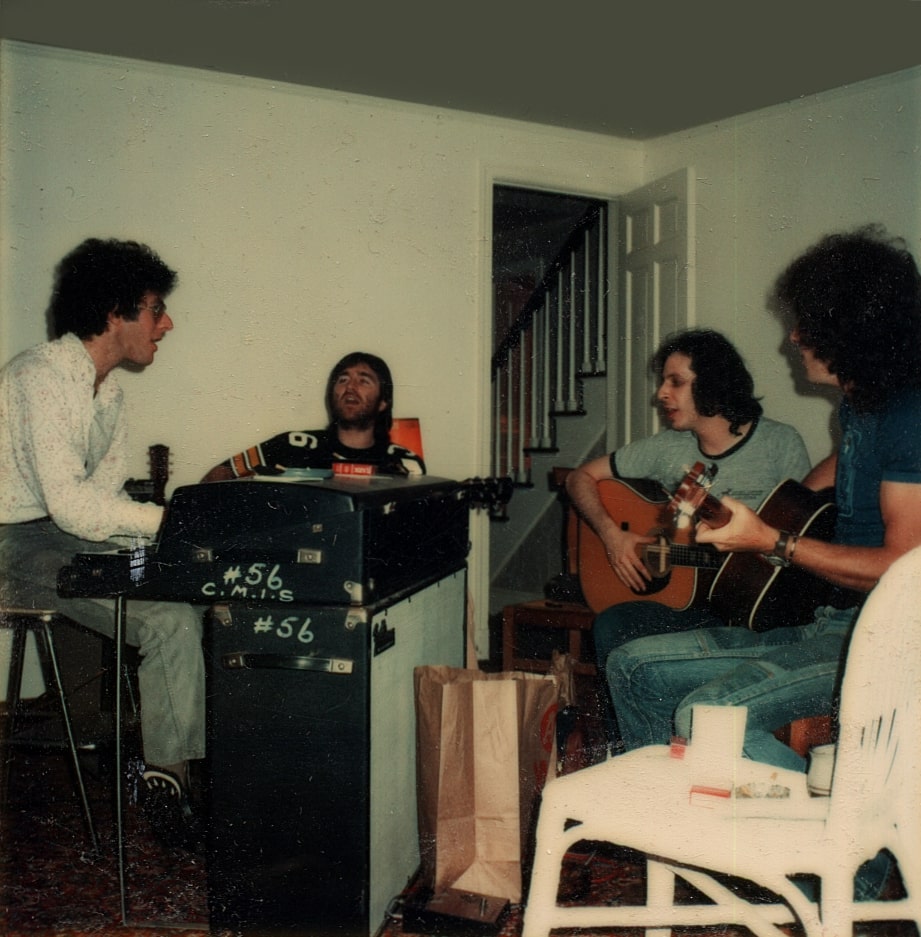

What about American Flyer? You were joined by Eric Kaz, Craig Fuller from Pure Prairie League, and Doug Yule from The Velvet Underground. The first of your two albums were produced by George Martin. How was to work with producer George Martin? You were probably curious how the production will sound like?

George was brilliant and one of the nicest people I’ve ever known. He brought his Tannoy monitors from England to Indigo Studios in Malibu CA for our sessions. I learned a lot from working with George, especially little tricks he used with the Beatles, how he approached a rhythm section, and how he was able to interpret our songs. You can hear George’s touches all over the album, especially in his arranging for orchestra and background vocals. Working with George Martin will always be one of the fondest memories of my life.

In the late seventies you became East Coast Director of A&R and later Vice President of Mercury Records. What are some of the strongest memories from being VP at Mercury?

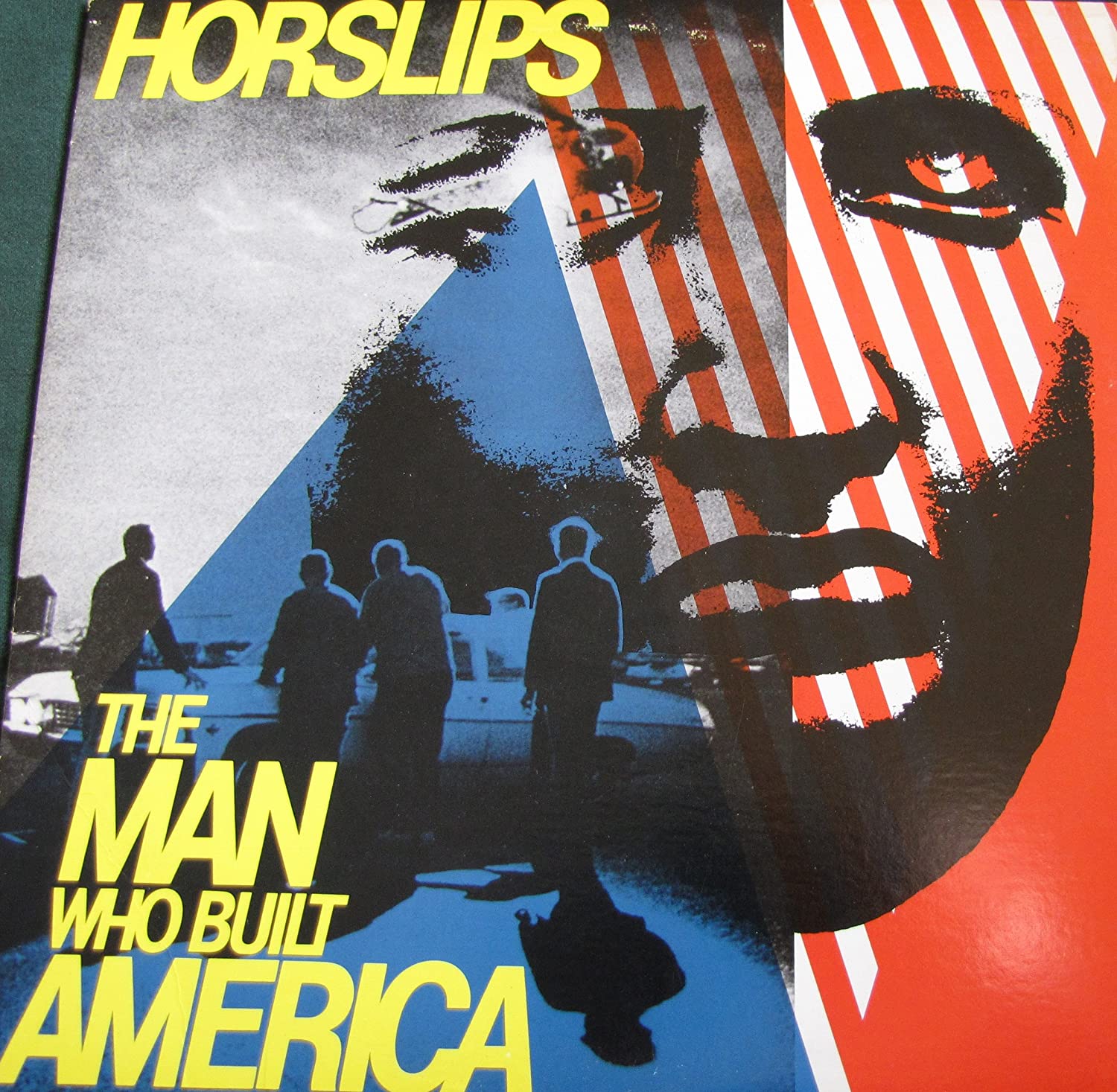

That I was able to pay alimony, for one thing. I didn’t like the job, except for my expense account. I never had a secretary before and didn’t know exactly what she was supposed to do, so on my first day on the job, I sent her home to walk my dogs. I didn’t like being in the position of judging other people’s music. And I didn’t like being at Mercury Records where I might as well have been selling shoes. I was there during the disco days and had to listen to some awful bands live and some even worse demos. When I had to see a group at a club downtown once, I had my secretary call to get my tickets comped. The club refused, and so I threatened that I would never come down there again and no acts would ever be signed out of their club. The gave in. I went down to see the band and as I walked up to the entrance, I saw a sign that said “Rock for Peace Night – Admission $2”. I said to myself, “What the hell am I doing?”, signed Horslips and wound up in the studio and away from my office as much as I could.

Around this time your love for Ireland came from the music of Horslips.

I loved working with Horslips. We did three albums together. And I loved spending all that time in Ireland. The band turned me on to some great Irish traditional music – music that I had never heard before, and I added it to my list of first loves along with blues, bluegrass, and old timey music. There was a tradition and history in Irish music that I had never known about before. Horslips were carrying on that tradition in a unique and powerful way. They also gave me a new perspective on modern independent rock at the time. I was thrilled to be out of my office and hanging with musicians again. The first album we did was The Man Who Built America which should have done better than it did in the States. I was very disappointed that the record company wasn’t able to do a better job with it.

What were the circumstances behind managing Green Linnet Records?

After leaving Mercury and with my newfound love of Celtic folk music, I was introduced to Wendy Newton who owned Green Linnett Records. Wendy was looking for a general manager and the Green Linnett office was not that far from my house. It worked out well and I learned so much about being with a small independent record company – record promotion, distribution, artist relations – it was a whole other kind work than what I was used to.

How did you meet your future wife Alison Palmer, a well known ceramic artist…

Alison was a friend of some friends who were helping me move my out of house. We met at a diner nearby. I went to see her work at her studio and fell in love with it and with her. I think I even stalked her for a while. I can’t imagine being in quarantine with anyone else in this world other than my wife.

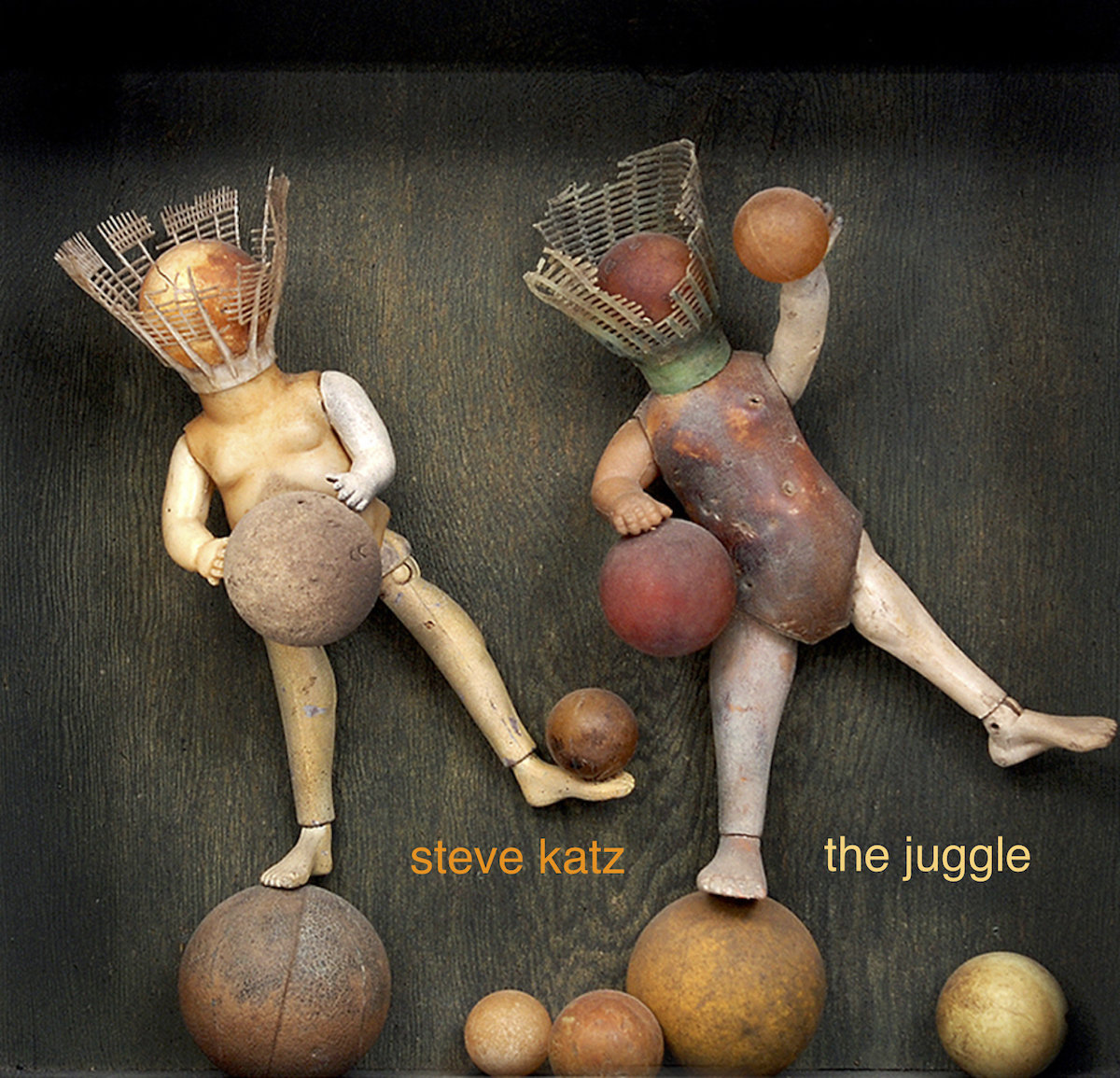

Can you share some further details how your latest album The Juggle was recorded?

I never did my own solo album, although I had come close at various times in my career. Recently, I decided to do an acoustic retrospective and to do it Bob Dylan style, in as few takes as possible. Friends of mine have a studio not far from me and they asked me to do a live show there. We decided to record the show, since we were there in the studio anyway. We used about five tracks from the live recording and I added more in the weeks that followed. I also added a couple of extras – one being a late night recording of Lou Reed’s “Sweet Jane” done in Toronto in 1974 – me singing and Lou on acoustic guitar. I felt, as it was one of the best vocals I had ever done on one of the greatest songs ever written, that it should be put out there, so I put it on The Juggle.

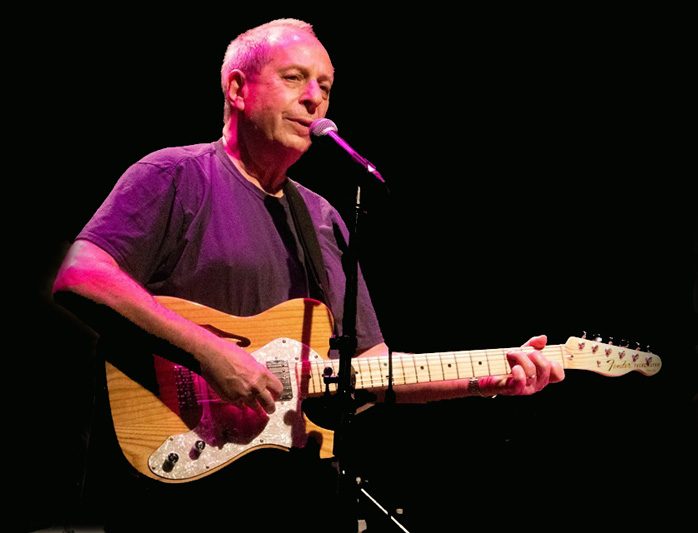

What currently occupies your life?

Alison and I have a pottery business. We do workshops at our studio and Alison, with her own work, gets invited to high end shows like the Smithsonian Craft Show. I do solo concerts and book talks. All this has come to a halt with the pandemic. Shows and workshops have been cancelled.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

People always ask me this. It’s so hard to give an honest answer. Let’s just say that my favorite albums are the ones I am listening to at any given time and that I love at the moment. Steve Katz

– Klemen Breznikar

Steve Katz Official Website

All photo materials are copyrighted by their respective copyright owners, and are subject to use for INFORMATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY!