Bob Dylan – ‘Rough and Rowdy Ways’ (2020)

Bob Dylan Releases Brilliant Songs: “Murder Most Foul,” “I Contain Multitudes,” and “False Prophet”– Ahead Of His New Album ‘Rough and Rowdy Ways’.

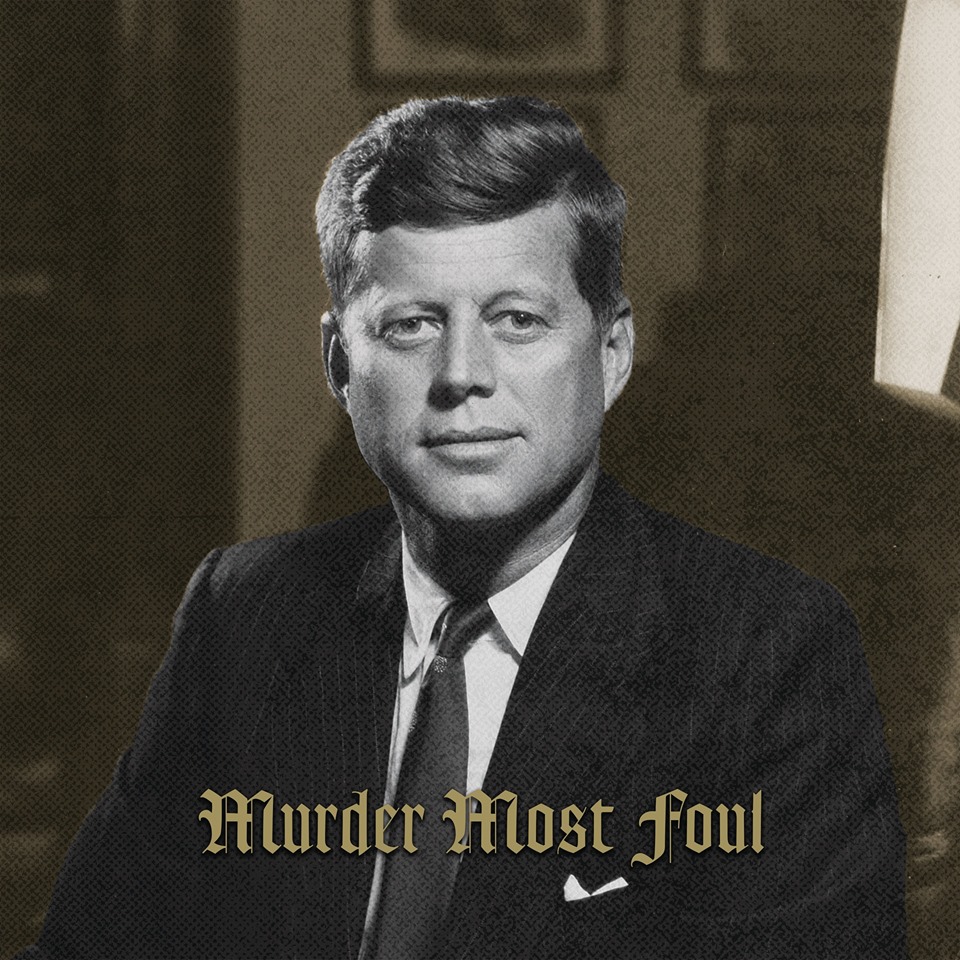

Bob Dylan, on midnight March 27, unearthed and released a previously unreleased song, “Murder Most Foul,” (taking its title from lines in William Shakespeare’s Hamlet) which is an elegy to JFK as well as a lament for an America which no longer exists. Over piano and strings, a melancholic yet wry Dylan delivers an almost seventeen-minute-long powerful stream of consciousness rap full of references to pivotal musical and cultural figures, songs, and films which defined the 20th century American experience.

The song begins with: “It was a dark day in Dallas, November ’63/A day that will live on in infamy,” addressing JFK’s assassination as a life-altering moment for the United States and for the Baby Boomer generation in particular; much as December 7, 1941 was the infamous day which their parents–The Greatest Generation–endured.

Among the many cultural touchstones referenced in Dylan’s lyrics are: The Beatles, and the impact of Liverpool’s Mersey Beat sound by bands such as Gerry and the Pacemakers on a post-JFK USA as 1964 ushered in the British Invasion (“The Beatles are comin,’ they’re gonna hold your hand/Slide down the banister, go get your coat/Ferry ‘cross the Mersey and go for the throat“); The Who (“Tommy can you hear me? I’m the Acid Queen); The Everly Brothers, and Jesse Jackson (“Wake up, little Susie, let’s go for a drive/Cross the Trinity River, let’s keep hope alive“); Larry Williams, and Patsy Cline (“You got me dizzy, Miss Lizzy, you filled me with lead/ That magic bullet of yours has gone to my head/I’m just a patsy like Patsy Cline“). Also referenced directly are the Aquarian Age, Woodstock, and Altamont–the zenith and nadir of the counterculture music festivals; the Grassy Knoll, Dealey Plaza, Elm Street (“Living in a nightmare on Elm Street“–here Dylan juxtaposes the street on which JFK was shot with Wes Craven’s famous slasher film), Parkland Hospital, and Love Field (all historically relevant Dallas, Texas locations associated with JFK’s murder); Deep Ellum, Texas–a pivotal place for the early jazz and blues music scene, Dylan has also covered the song “Deep Ellum Blues” in the past; JKF assassin and “patsy” Lee Harvey Oswald, as well as Oswald’s assassin Jack Ruby (“Play it for that strip club owner named Jack“); Vice President-become-successor-President Lyndon Baines Johnson; the Zapruder film which captured the moment of JFK’s death; blues legends Etta James and the song “I’d Rather Go Blind,” John Lee Hooker and the song “Scratch My Back,” and Guitar Slim; jazz masters Jelly Roll Morton, Bud Powell, Oscar Peterson, Stan Getz, Thelonious Monk, Art Pepper, and Charlie “Yardbird” Parker; gangsters Bugsy Siegel (perhaps due to Siegel’s Mob connection to the Las Vegas Strip, and JFK’s connection with Frank Sinatra and the Rat Pack?), and Pretty Boy Floyd (perhaps because JFK was sometimes contemptuously referred to as a “pretty boy” by his detractors? Or perhaps as an homage to Dylan’s mentor, Woody Guthrie, and his outlaw-hero folk song “Pretty Boy Floyd,” which was covered by both Joan Baez and also The Byrds on the seminal album Sweetheart of the Rodeo–which paved the way for the country rock genre); Hollywood icons Marilyn Monroe (with whom JFK allegedly had an affair), Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd (one of Lloyd’s classic silent films is called Safety Last! –this might be Dylan’s indirect way of inferring that JFK’s decision to ride in a limousine with the top down in Dallas was unsafe and cost him his life; also JFK’s father, Joseph P. Kennedy, became a Hollywood film studio mogul during the silent age of cinema); Eagles members and Texans Don Henley and Glen Frey and the song “Take It To The Limit;” Beach Boys member Carl Wilson; Allman Brothers Band member Dickey Betts and the song “Blue Sky;” Fleetwood Mac members Lindsey Buckingham and Stevie Nicks; disc jockey Wolfman Jack (who had a cameo in George Lucas’s classic film American Graffiti–which dealt with coming of age in the early rock ‘n’ roll era prior to JFK’s assassination); escape artist Harry Houdini; and convicted murderer Robert Stroud–the “Birdman of Alcatraz” (who in fact died the day before John F. Kennedy was assassinated).

Oblique and not so oblique references are also sprinkled throughout Dylan’s lyrics to this song: to First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy (“Ridin’ in the back seat next to my wife“); Robert and Ted Kennedy (“Your brothers are comin’, there’ll be hell to pay“); blues great Robert Johnson (“I’m going down to the crossroads, gonna flag a ride“); Abraham Lincoln–as a fellow US President who was assassinated (“I’m riding in a long, black, Lincoln limousine“); Martin Luther King Jr and Pope Paul VI (“Play it for the reverend, play it for the pastor“); Little Richard and his song “Send Me Some Lovin’;” Ray Charles and his song “What’d I say?;” Bert Bacharach & Hal David and the songs “What’s New, Pussycat?” and “Walk on By;” William Guy Banister–who some alleged had been a co-conspirator in the JFK assassination (“Slide down the banister“), and also alleged co-conspirator David Ferrie (“Ferry cross the Mersey“); the “Three Tramps” escorted by police through Dealey Plaza on the day of JFK’s assassination–their presence in close proximity to the crime later leading to conspiracy theories (“There’s three bums comin’ all dressed in rags“); former Texas First Lady Nellie Connally (here Dylan goes for bitter irony with the lyrics:”Don’t say Dallas don’t love you, Mr. President“–in reality, Nellie Connally said: “Mr. President, you can’t say Dallas doesn’t love you.” Those may have been the last words JFK ever heard shortly before he was assassinated); JFK’s famous “Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country” speech (“Don’t ask what your country can do for you“–again, Dylan goes for bitter irony here, the inference seeming to be that dark forces in America conspired to kill JFK); country music stars the Louvin Brothers and George Jones (“Cash on the barrelhead, money to burn“– The Louvin Brothers have a song called “Cash on the Barrelhead,” and George Jones has a song called “Money To Burn,” but Dylan’s inference might be referencing the notion of well-connected and wealthy conspirators putting a hit on JFK–or that the Kennedy connections in essence “bought” JFK the presidency with the Mafia’s “help,” as Joseph Kennedy had power, influence and “money to burn”); the racist Jim Crow laws associated with the Southern States up until the mid-’60s (“Better not show your face after the sun goes down“); Motown artists Jr. Walker & the All Stars’ song “Shotgun,” and African American author Ralph Ellison and his novel Invisible Man–alluding to the Civil Rights movement (“Shoot him while he runs, boy, shoot him if you can/See if you can shoot the invisible man”); the film Goodbye Charlie–a 60’s comedy about a womanizer who is shot and killed and whose consciousness returns in a woman’s body (“Goodbye, Charlie, goodbye, Uncle Sam” — here it is likely that Dylan is both referencing JFK’s fabled womanizing as well as referencing the Vietnam War; as the Viet Cong were called “Charlie”); the American Civil War novel and film Gone With The Wind (“Frankly, Ms. Scarlett, I don’t give a damn“–here Dylan paraphrases the classic lines which Clark Gable, as the womanizer Rhett Butler, spoke in the iconic if controversial film–the inference perhaps being that JFK’s assassination, occurring in the South during the Civil Rights era, laid bare that the issue of systemic racism, and anti-Yankee sentiment associated with the attempted succession of the South and the outbreak of the Civil War of one hundred years prior had never really been resolved; furthermore, lyrically, Dylan sets up a juxtaposition between the American Civil War and Vietnam’s Civil War with the inference that, just as the Confederate South was fighting for “a Lost Cause,” the U.S.–under President Nixon–eventually pulled out of South Vietnam in 1973, seeing it as “a Lost Cause” as well; a further irony being that a CIA-backed South Vietnamese military coup lead to the assassination of South Vietnam’s President Ngô Đình Diệm on November 2, 1963–and just twenty days later, on November 22, 1963, JFK was assassinated); the notion of “truth” in our post-truth political age (“What is the truth, and where did it go?.” Here Dylan might also be referencing the Gospel of Saint John 18:38, when Pontius Pilate says “What is truth?”–drawing a comparison between JFK’s assassination and Christ’s crucifixion); the song “Uranium Rock” by Warren Smith; Billy Joel and his song “Only The Good Die Young” –JFK was only 45 at the time of his death; the folk ballad “Tom Dooley,” popularized by The Kingston Trio; “St. James Infirmary,” popularized by Louis Armstrong, and the song “Please Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood”–bringing to mind both Nina Simone’s definitive version as well as The Animals amazing cover version; Warren Zevon and his song “Desperados Under the Eves” (Dylan references Zevon’s closing lyrics pertaining to looking away down Gower Avenue in Hollywood–which, coincidentally, Carl Wilson sang as the coda to Zevon’s song); “Tragedy” by The Fleetwoods, and “Twilight Time” by The Platters; the Bob Wills and The Texas Playboys western swing song “Take Me Back To Tulsa,” juxtaposed with the horrible Tulsa race massacre of 1921 (Take me back to Tulsa to the scene of the crime); Queen and its song “Another One Bites the Dust”–alluding to the tidal wave of political assassinations that shook America and the world throughout the Sixties; George Bennard, composer of the gospel hymn “The Old Rugged Cross,” and punk band The Dead Kennedys and its album “In God We Trust, Inc.;” the film noir Ride the Pink Horse, based on the novel of the same name by Dorothy B. Hughes; Frank Sinatra and the song “Lonesome Road;” Elvis Presley and the song “Mystery Train,” and Sun Ra–referred to as “Mr. Mystery.” There are probably more references…

Dylan concludes the lyrics to “Murder Most Foul” by invoking the titles to a cornucopia of sentimental ballads from the Great American Songbook by Erroll Garner & Johnny Burke, Burton Lane & Yip Harburg, Cole Porter, Hoagy Carmichael & Paul Francis Webster, Jimmy Van Heusen & Eddie DeLange, including: “Misty” (here also punning on the Clint Eastwood film Play Misty for Me) “That Old Devil Moon,” “Anything Goes,” “Memphis in June,” “Deep in a Dream;” as well as juxtaposing Randy Newman’s tune “Lonely at the Top” with the Dalton Trumbo-scripted film Lonely Are the Brave (which featured Kirk Douglas as a freewheeling, Korean War veteran and non-conformist ranch hand cowboy who tries to be an individualist in a world that won’t let him–JFK screened this film at the White House in 1962); Beethoven’s “Moonlight Sonata;” Clyde McPhatter & The Drifters and “Lucille;” Roosevelt Sykes and a “Driving Wheel;” Little Walter and “A Key to the Highway;” Julie London and “Cry Me a River;” the pre-Code romantic comedy film It Happened One Night, and Smiley Lewis and “One Night of Sin;” Nat King Cole and “Nature Boy;” Billy Joe Royal and “Down in the Boondocks” (written by Joe South, who also played guitar on Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde album), and Marlon Brando as Terry Malloy– the disillusioned dockworker who could have been a contender– in the classic film On the Waterfront; Shakespeare’s controversial play Merchant of Venice and the phrase “Merchants of Death,” (originally used negatively to describe industries and banks which supported and financed World War I, here the implied reference is to the Cold War-era Military-industrial complex–which President Eisenhower warned about in his farewell address); the jazz standard “Stella By Starlight” by Victor Young and Ned Washington, originally composed for the film The Uninvited, and Shakespeare’s Lady Macbeth (perhaps the implied “Out, damned spot!” reference harking back to the blood on the hands of the presumed JFK assassination conspirators); Marching Through Georgia”–a Union Civil War song by Henry Clay Work–and “Dumbarton’s Drums”–a traditional Scottish song; Leonard Cohen and “Darkness,” and The Tragedy of Julius Caesar by Shakespeare (“…and death will come when it comes“–here Dylan is comparing the assassination of JFK with the assassination of Julius Caesar…also, Marlon Brando played Julius Caesar in the film of the same name); “Love Me Or Leave Me” by Walter Donaldson and Gus Kahn; and “The Blood Stained Banner” (here it would appear that Dylan has a double reference–a lyric from a gospel song called “Soldiers of the Lord,” and also the name given to one of the flags created by the Confederacy in 1865). Finally, the song concludes with the lyrics: “Play ‘Murder Most Foul’.”

“Murder Most Foul” offers up an interesting comparison with Don McLean’s classic song “American Pie” regarding the impact of the turbulent Sixties on “a generation lost in space,” as well as Billy Joel’s “We Didn’t Start The Fire” – a list song which chronicles The Cold War period from the late 1940s-1980s, yet it is equally compelling to listen to it and then listen to other songs which have dealt–oftentimes morbidly–with the shock and outrage of JFK’s assassination; including, but not limited to, the punk rock songs “Bullet” by The Misfits, and “The Amerikan in Me” by The Avengers– as well as “Give The People What They Want” by British rock stalwarts The Kinks.

As far as Dylan’s timing on finally releasing this song, it is interesting to speculate if he sees the COVID-19 pandemic as the final nail in the coffin of the American Dream and the–largely–unfulfilled promise of JFK’s New Frontier. Despite the legend of JFK’s presidency being a Camelot of the early 1960s, it should be stated that JFK was never as proactive as he should have been when it came to advancing Civil Rights legislation. I should also note that since I began working on this article, the U.S, and, indeed, the World, has been rocked by the George Floyd protests which have resulted in a demand for proactive change against systemic racism, police defunding and accountability, and equal justice under the law for black lives, people of color, and other disenfranchised peoples; and might yet lead to such things as a Basic Universal Income being instituted for many millions of people out of work through no fault of their own due to the pandemic. In fact, it is hard not to also think of one of Dylan’s greatest songs: “Tangled Up In Blue” in this current zeitgeist, which in some ways is trying to rectify some of the issues which were never fully resolved in the Sixties–and the lyrics: “I lived with them on Montague Street/In a basement down the stairs/There was music in the cafes at night/And revolution in the air.” As well, Dylan’s masterpiece “Desolation Row” comes to mind in this epoch of mass protest and civil unrest, with it’s opening lyrics of: “They’re selling postcards of the hanging/They’re painting the passports brown/The beauty parlor is filled with sailors/The circus is in town/Here comes the blind commissioner/They’ve got him in a trance/One hand is tied to the tight-rope walker/The other is in his pants/And the riot squad, they’re restless/They need somewhere to go/As Lady and I look out tonight/ From Desolation Row.” Indeed, has the entire Western World become “Desolation Row”–or was it always so, hidden under a thin plastic veneer?

Verse three of “Murder Most Foul” brings it all back home as Dylan intones: “They mutilated his body and they took out his brain/What more could they do? They piled on the pain/But his soul was not there where it was supposed to be at/For the last fifty years they’ve been searchin’ for that/Freedom, oh freedom, freedom over me/I hate to tell you, mister, but only dead men are free.”

Bob Dylan’s second new release, which dropped on April 17, “I Contain Multitudes,” takes its title from a line in Walt Whitman’s celebrated poem “Song of Myself” from Leaves of Grass. This seems fitting, as many Dylan fans would argue that he could be considered a spiritual heir to Walt Whitman and his Transcendentalist American poetry. By contrast to “Murder Most Foul,” “I Contain Multitudes” finds Dylan in a playfully wry–perhaps even insouciant–mood. Over a melodic guitarline which at times brings to mind the one from Smokey Robinson’s classic Motown hit “The Tracks of My Tears,” Dylan lays out lyrics which–intentionally or not–make me think of the song craft of the late, great Leonard Cohen, and “Tower of Song” in particular.

“I Contain Multitudes” begins with: “Today, and tomorrow, and yesterday, too/The flowers are dyin’ like all things do,” with which Dylan seems to reference Shakespeare’s famous soliloquy from Macbeth:

“To-morrow, and to-morrow, and to-morrow,

Creeps in this petty pace from day to day,

To the last syllable of recorded time;

And all our yesterdays have lighted fools

The way to dusty death. Out, out, brief candle!

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player,

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage,

And then is heard no more. It is a tale

Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury,

Signifying nothing.”

Dylan could also be giving a nod and a wink to The Beatles and the album Yesterday and Today (there is speculation that the song “Dr. Robert,” which appears on Yesterday and Today, might be about Bob Dylan, who introduced The Beatles to marijuana.). Dylan might also be acknowledging Pete Seeger’s iconic anti-war folk song “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?”

Dylan almost definitely pays tribute to Nineteenth century Irish bard Antoine Ó Raifteirí and his poem “The Lass from Bally-na-Lee,” when in the next line he states: “Follow me close, I’m going to Bally-na-Lee.” Elsewhere, Dylan salutes Edgar Allen Poe and “The Tell-Tale Heart;” William Blake and his Songs of Innocence and of Experience; Anne Frank; Beethoven; Chopin; fellow Sixties alumni The Rollings Stones; and the fictional film adventure hero Indiana Jones.

“I Contain Multitudes” also features veiled references to some of Dylan’s early rock ‘n’ roll and rockabilly heroes. Dylan’s lyric: “Got Skeletons in the walls of people you know” appears to be a pastiche on Bo Diddley’s lyrics: “I got a brand new chimney made on top/Made out of a human skull” from “Who Do You Love?” The lyrics: “A red Cadillac and a black mustache” are actually the title of a Sun Records song sung by Warren Smith (of which Dylan himself has recorded a cover version); the lyrics: “Pink pedal-pushers, red blue jeans” pay tribute to Carl Perkins and his rockabilly song “Pink Pedal Pushers” (which was more than likely the inspiration for The Stray Cats’ “Stray Cat Strut”) and also to Gene Vincent and His Blue Caps’ rockabilly song “Red Blue Jeans and a Pony Tail.” It is important to remember that the future Bob Dylan–when he was still Robert Zimmerman– listened to early rock ‘n’ roll music as an American teenager of the late 1950s (and had a deep appreciation of the late, great Little Richard’s music in particular) and even covered rock ‘n’ roll songs while he was a high school student with his band The Golden Chords.

The lyrics: “All the pretty maids, and all the old queens/All the old queens from all my past lives” seem to source the old English nursery rhyme:

“Mary, Mary, quite contrary

How does your garden grow

Silver bells and cockle shells

Pretty maids all in a row”

The words to which are also featured in Rufus Thomas’ lyrics for “Walking the Dog”– a song The Rolling Stones covered on their debut album England’s Newest Hit Makers. However, the “pretty maids all in a row” lyric is also contained in Dylan’s song “Red River Shore,” from The Bootleg Series Vol. 8: Tell Tale Signs: Rare and Unreleased 1989-2006. With the “all the old queens” lyric, Dylan might be slyly referencing bohemian homosexual friends and acquaintances from his back pages such as Allen Ginsburg, Andy Warhol and other superstar personalities at The Factory, etc., and cleverly juxtaposing it with “all the old queens from all my past lives,” inferring significant lost loves, ex-girlfriends such as Suze Rotolo, and his ex-wives–Sara Dylan, and Carolyn Dennis.

The lyrics “I’ll sell you down the river, I’ll put a price on your head/What more can I tell you? I sleep with life and death in the same bed” hark back to Dylan’s Billy Theme 4 lyrics from the Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid soundtrack album, for Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 film (in which Dylan enjoyed a small part as a character named Alias); while the lyrics: “I rollick and I frolic with all the young dudes” are, no doubt, inspired by David Bowie’s song “All the Young Dudes”–best known via the Mott the Hoople rendition. And the lyrics: “I live on a boulevard of crime” was most likely inspired by the classic 1945 French film by Marcel Carné, Les Enfants du Paradis, which takes as a locale Boulevard du Temple–cynically referred to as the “Boulevard du Crime.” Interestingly, Baptiste, a protagonist of the film, is a mime who appears in white face makeup–and Dylan likewise wore white face makeup during his Rolling Thunder Revue days.

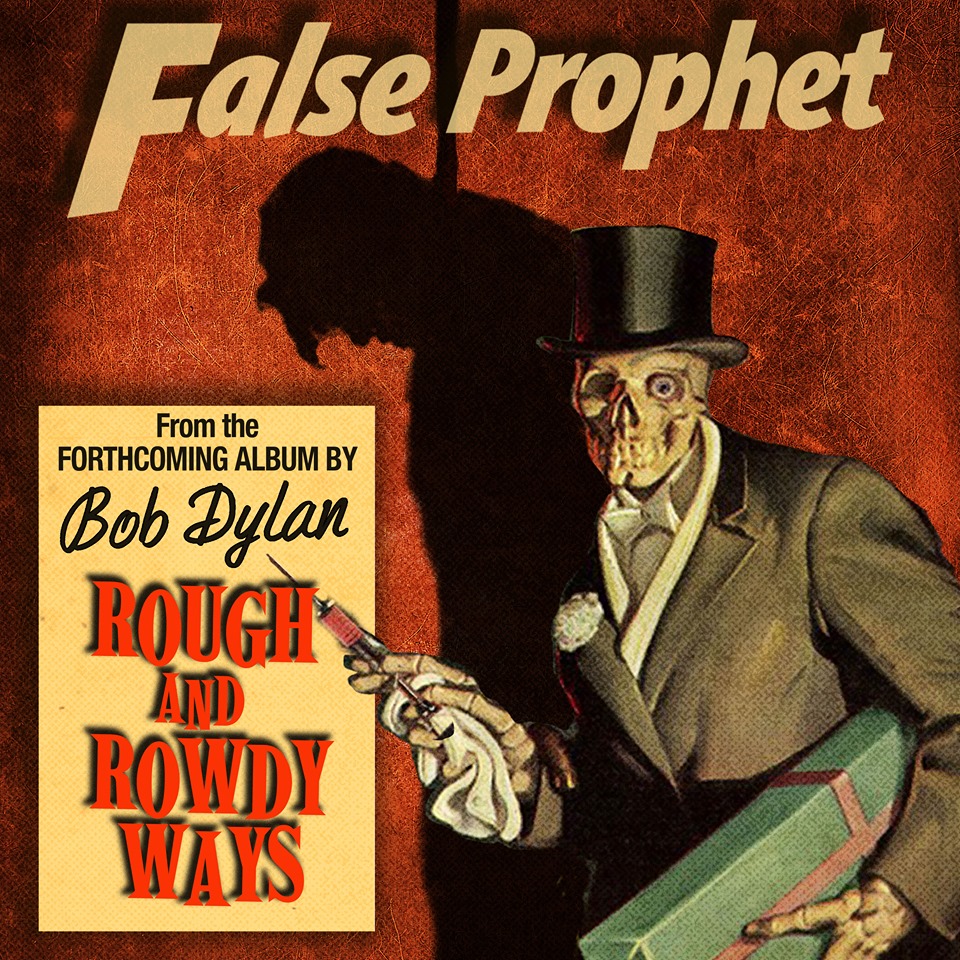

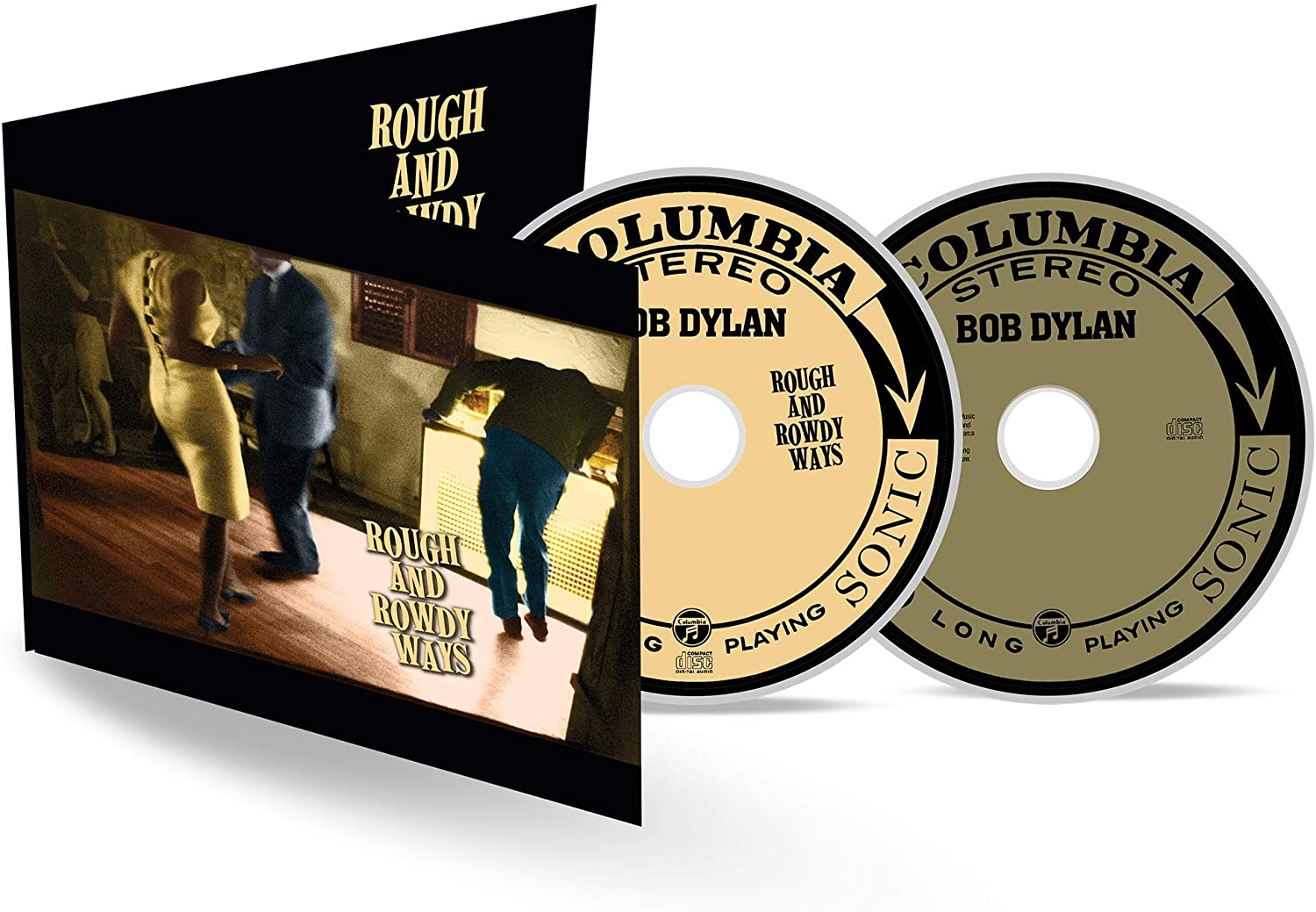

“False Prophet” is Dylan’s third song to drop in 2020–on May 8–along with the announcement of a new album slated for “Juneteenth” or Freedom Day (June 19, 2020), to be titled Rough and Rowdy Ways, which will also contain the songs “Murder Most Foul,” and “I Contain Multitudes.” “False Prophet” is a sturdy blues strutter, on which Dylan pays homage to the Ike Turner guitarline from Billy “The Kid” Emerson’s 1954 song “If Lovin’ is Believing.” The album’s other tracks are: “My Own Version of You,” “I’ve Made Up My Mind to Give Myself to You,” “Black Rider,” “Goodbye Jimmy Reed,” “Mother of Muses,” “Crossing the Rubicon,” and “Key West (Philosopher Pirate)”.

By contrast with Dylan’s last three tepid Tin Pan Alley-themed covers albums, “Murder Most Foul,” “I Contain Multitudes,” and “False Prophet” are potent reminders of what America’s greatest badass Nobel Prize awarded troubadour is still capable of when, like a phoenix arisen, he sings the body electric and his aim is truth. Not that there was ever any doubt!

– Sean Mageean

Bob Dylan Official Website

great article