Twenty-Five Views of Worthing | Interview

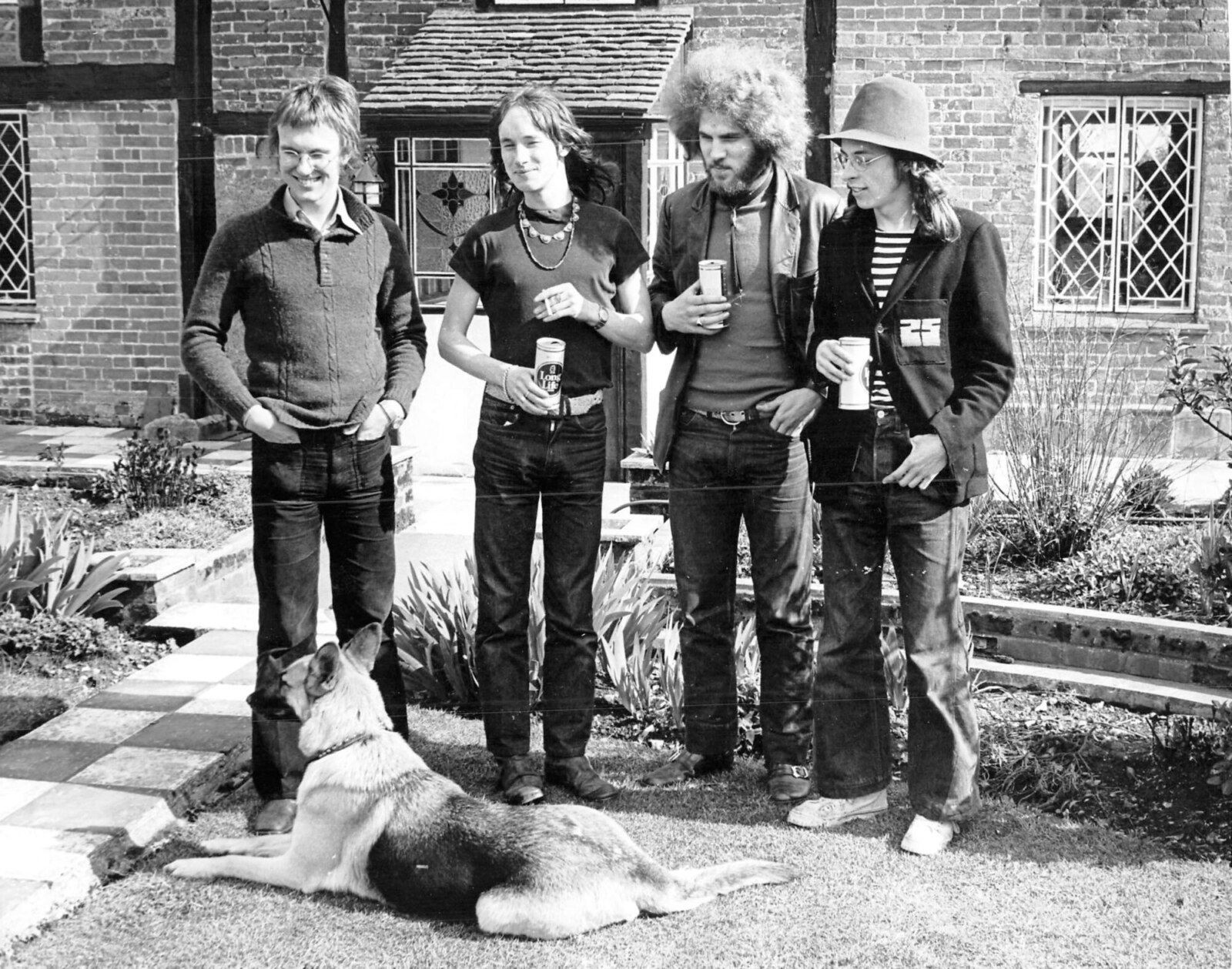

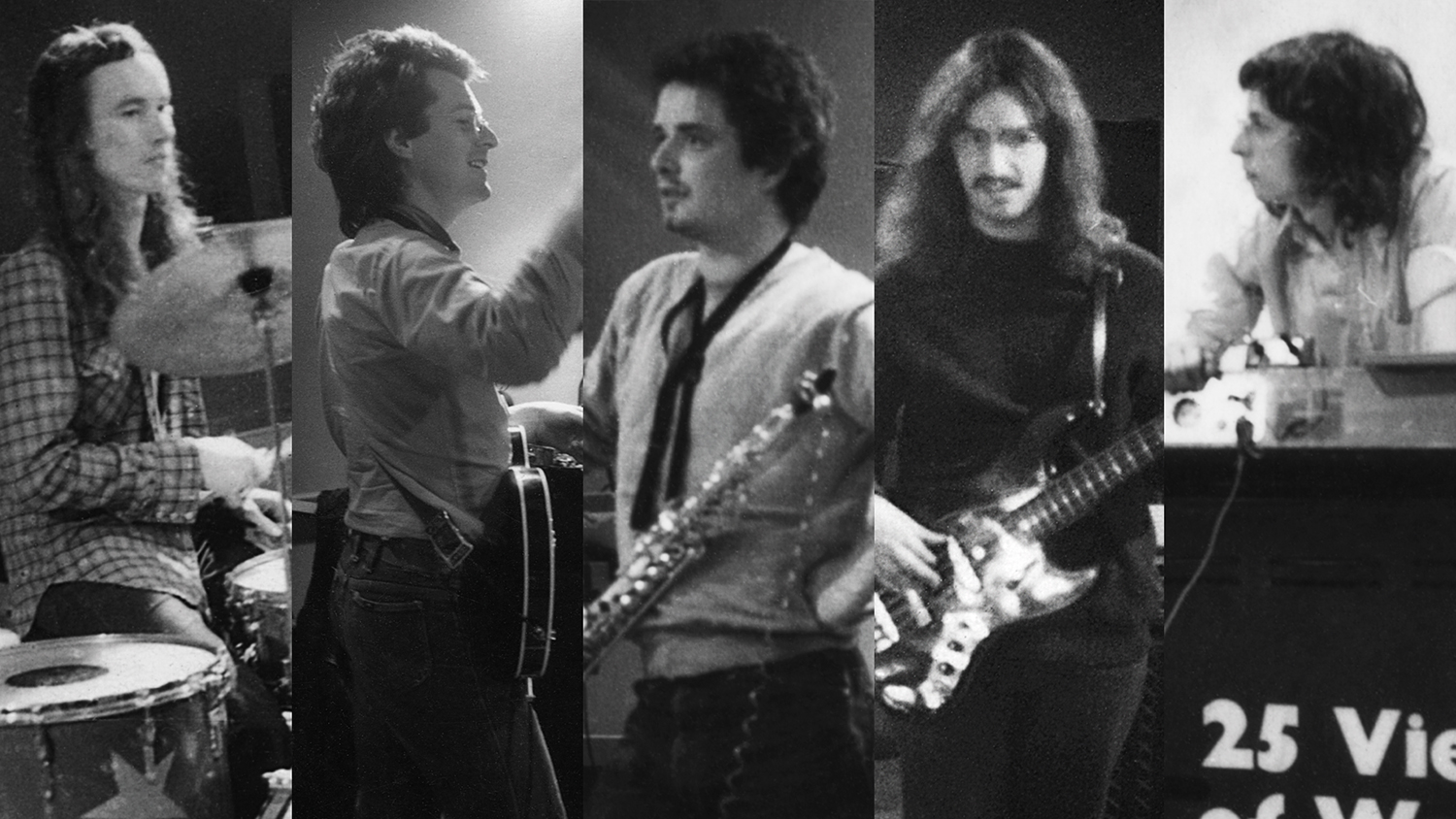

Twenty-Five Views of Worthing were formed in 1970 by Watford school friends Roger Hillier and Mark Sugden out of the ashes of their psychedelic band Primrose Path. They were signed to a management deal with Island Artists in 1972 and supported the likes of Genesis, Caravan and Mott the Hoople, although a recording contract with Island Records never transpired.

The band recorded several tracks using downtime at Island’s Basing Street Studio, which have never previously been released. Continuing with various line-ups throughout the ‘70s, the band also cut a rare independent EP in 1977. The band left behind a rich legacy of recorded material which is finally presented on a LP for the first time via Wind Waker Records.

Would you like to talk about your background? Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

Roger Hillier: I think I should start by saying that I’ll do my best but I have a very bad memory. My parents didn’t get on well at all, and my childhood memories include a lot of angry shouting and flying crockery. I found this terrifying and tried to block it out.

I was born in my parents’ house in Kingsbury, in suburban north-west London. My dad, Charles, came from Notting Hill and my mum, Winifred, was from Kensal Green. During the Second World War Charles was an engine fitter in the RAF, working on Sunderland flying boats. He was now working in the office of a nearby factory that made parts for motor vehicles, while Win stayed at home looking after the house, and me.

My parents were both amateur musicians. My mother played violin, and my father played piano, but by the time I came on the scene they both seemed to have given up. We had no musical instruments in that first house, apart from my mum’s fiddle, which I don’t think she ever played, or if she did it was very rare. As a young man, my dad played the organ in a church near to where he lived. I remember him telling me about the acoustic delay. He said that when playing an accompaniment it was important not to listen to the choir, or the music would eventually grind to a halt.

Although nobody played anything, we did listen to a lot of recorded music—possibly 78 rpm discs on a wind-up gramophone. Then my dad, who was susceptible to new gadgets (we once had a gas-powered fridge), bought a Bush radiogram. It was enormous, made of highly-polished veneered wood. Lifting the heavy lid revealed the radio with its dials and knobs on the left, and on the right was the record player.

The records we had were mostly classical—Mozart, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, Rossini, nothing too challenging. Sometimes Win listened to Kathleen Ferrier (who had recently died, at the age of 41) singing ‘What is Life’, from Gluck’s Orpheus and Eurydice, and wept. I also remember the big band leader and pianist Charlie Kunz’s piano medleys, and we had a record of the Singing Dogs. This novelty record was in a way an early example of sound sampling, a technique I became very interested in many years later. The makers of this record chopped up tapes of dogs barking and made the dogs ‘sing’ popular songs with a simple accompaniment. If that weren’t bad enough, we also had a copy of ‘Elizabethan Serenade’, by Ronald Binge. To this day I would rather listen to a cat sliding down a blackboard (no offence Ron, it’s just a matter of personal preference).

When did you begin playing music?

My first public performance was when I was about four or five years old and took place in Wembley Town Hall (I think it’s now called something else), with an orchestra of children from my school. My instrument was the triangle. I didn’t choose the triangle. I think it was given to me to play because it was the instrument that could do the least damage.

Soon after that my parents split up. My mother went to live with her sister Elsie in Watford, a town north-west of London, and my nan (my dad’s mother) came to live with us in Kingsbury. I found this confusing, and it was some time before I realised that my mother had been having an affair with a man called, appropriately enough, Dick, who lived opposite. Eventually, my parents came to some sort of agreement and, when I was six, the three of us moved into a house in Watford. An uneasy truce began which lasted for the rest of their lives. Dick also moved to Watford, and became a good friend when I grew up.

When I was about nine or ten, my auntie Elsie gave me her piano. I don’t know why she had a piano, I don’t think she played it herself, but I was really pleased. I was taught to play by a woman who lived in the next street. The first simple tunes were so simple that I found I could play them without looking at the score. This was my undoing because even now, although I understand all (or at least most of) the symbols, I can’t read music well enough to play anything more complicated than the tunes I began with all those years ago. The part of my brain that can read words doesn’t seem to talk to the part that understands musical chords, intervals, melody etc. I didn’t let it bother me because I really wanted to make music, one way or another. I now believe that only a genius can be brilliant playing by ear, and since I’m not a genius, or Thom Yorke, I’ve had to adapt as best I can.

When did you decide that you wanted to start writing and performing your own music? What brought that about for you?

I discovered rock and pop listening to Radio Luxembourg on a transistor radio under my bed covers. Then, at the local church youth club, which was the only place nearby for a teenager to hang out, I met some other lads who were interested in music. One of those lads was Phill Brown, who played drums, and knew much more about the contemporary music scene than I did. Many evenings were spent in Phill’s room at his parents’ house, where I was introduced to, among others, the Who, the Small Faces, the Graham Bond Organisation, and Spike Jones and his City Slickers. I drank all this in, and smoked Phill’s fags (sorry Phill).

Phill and I put a band together called the Centaurs. We did instrumental versions of current hits. Phill’s party piece was our version of ‘Wipe Out’ by the Surfaris—a demanding tune for an aspiring drummer. Sometimes Phill got wiped out himself, and in his frustration the sticks would fly. I remember only one gig. I had blagged the loan of a Farfisa Compact organ from a local music shop—my first encounter with a ‘proper’ electronic keyboard. We were part of an amateur variety show in a school hall, and I’m sure we were terrible, but we did get a name check in the local paper.

It was some time before I thought seriously about writing music myself—possibly this didn’t happen until the Worthings came together. I guess it was a pragmatic decision. The band needed some music, so I would try to make some.

“The horns were connected to a propane gas cylinder, and belched flames high into the air.”

Twenty-Five Views of Worthing were formed out of the ashes of Primrose Path. What kind of material did you play in Primrose Path? Any recordings?

Primrose Path was essentially a covers band, with a leaning towards the psychedelic. The line-up was Mark Sugden (who instigated the project, and whom I met at school), on vocals and trumpet, Martin Harvey on violin and vocals, me on keyboards, Phil Howard-Jones on bass, and Gordon Hale on drums.

We had varying tastes, so the set was made up of a mix of different genres. We played Velvet Underground, stuff off the first Pink Floyd album, and a cover of a cover—the Vanilla Fudge arrangement of the Supremes’ ‘You Keep Me Hangin’ On’. On one occasion we tackled the intro to Richard Strauss’s tone poem ‘Also Sprach Zarathustra’, with Mark on trumpet and me playing the (probably wrong) chords.

My first instrument with Primrose Path was an ancient valve-operated organ, but I soon replaced it with a Vox Continental, which I loved for its space-age looks as much as its sound. Around the same time someone gave me a little metal box about the size of a tobacco tin (in fact I think it was a tobacco tin) that had two knobs on top and a jack socket for connecting to an amp. The box made weird, blood-curdling sounds and I wish I still had it. This device enabled us to play a chaotic version of ‘The Garden of Earthly Delights’, from the album The United States of America.

If Primrose Path lacked musical finesse, we made up for it with enthusiasm, and visual effects. These included a light show (projectors with layered glass slides injected with coloured ink and ether, which was boiled by the heat from the lamp) and a smoke machine. Also there was Janet, who sometimes joined us on stage as our go-go dancer.

The grand finale of a Primrose Path set soon became our version of Arthur Brown’s only big hit ‘Fire’, with pyrotechnics, created by our friend Ian Brister, that I thought more terrifying and dangerous than the original. Preceded by a scary vocal incantation from Martin, Mark would appear, robed, his face painted and partially covered by a silver mask and helmet bearing a pair of horns (acquired from a slaughter house). The horns were connected to a propane gas cylinder, and belched flames high into the air. I don’t know if it frightened the audience but it scared the shit out of me.

Primrose Path made one studio recording, in 1968. By that time Phill Brown had started working as a tape-op at Olympic Studios in Barnes, which was used by many of the big names in the rock/pop music industry. Phill suggested that Primrose Path come to the studio during some down time, and record a song he had written, and we did. This was a great experience, and gave me a taste for studio recording that I have enjoyed ever since. Our rendition of Phill’s song, ‘Rainbow in the Sky’, wasn’t perfect, but it was as good as we could make it. A few days later, while Phill was mixing the track, Nicky Hopkins wandered into the control room. Phill asked Nicky if he’d like to overdub some piano, which he did. Nicky’s reputation as a session musician was second to none, so we felt honoured, and the recording was much improved. ‘Rainbow in the Sky’ may yet appear on a vinyl 45 rpm single—a record company called Spoke Records has suggested this as a project, so we’ll wait and see.

Can you elaborate the formation of Twenty-Five Views of Worthing?

Mark was the driving force as ever. He had taped some Soft Machine when they were on John Peel’s Top Gear radio program. I was captivated by the unique sound, unusual time signatures and Mike Ratledge’s organ, which was put through a fuzz box and sounded like broken bottles. When Primrose Path split up it was obvious which direction we were going in. I say we, but I suppose I mean Mark and me. The crunch came when the drummer, Gordon, decided to quit. He said the music was getting too complicated.

Towards the end of Primrose Path we had been joined for some gigs by an old mate, Paul Devonshire, on saxophone, who now became the wind section of the new band. He often played two saxes at the same time, which sounded, and looked, impressive. As well as tenor and soprano saxophone, Paul played clarinet and flute. To complete the quartet we were joined by Paul Lindsay, on bass. Paul Lindsay, as well as providing solid, dependable, but inventive bass lines, also brought other essential skills that the rest of us lacked. He was quite sensible, knew about electronics and, given the opportunity, could probably have run a piss-up in a brewery without difficulty.

It was clear that the new band was going to be more focussed than Primrose Path. We recruited two friends, Jon Walls and Mick Harrison, to be roadies—they were bloody good, and worked their arses off. We bought a battered Ford Transit. Paul L immediately bolted heavy-duty hasps and padlocks onto each door, while Paul D, who knew about mechanics, took on the task of keeping the van running. Being fresh out of art school I was all for painting the van, which was a drab grey, in bright psychedelic colours, but Paul L explained to me kindly (or more likely not) that it would attract every thief who caught sight of it.

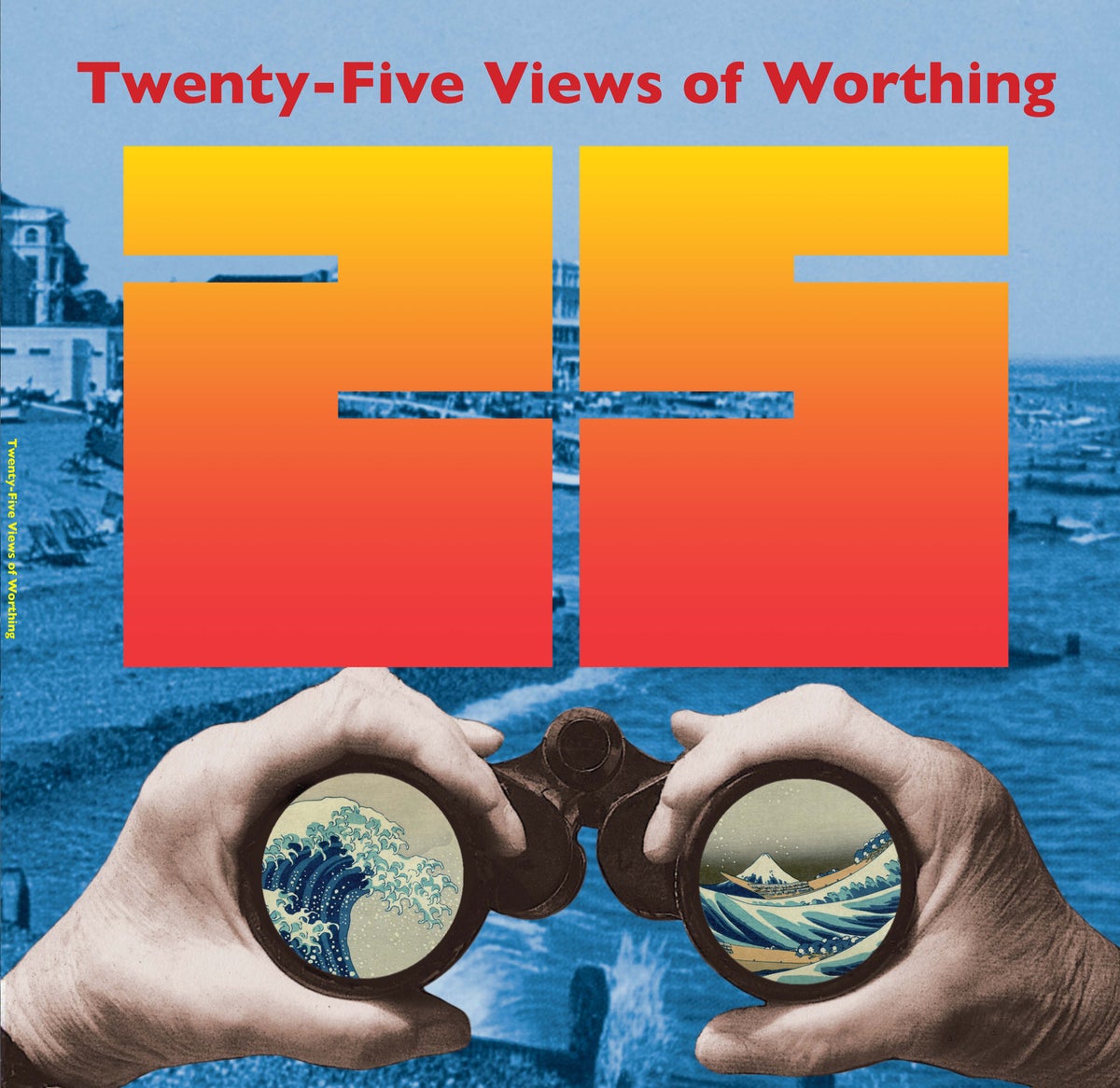

How did you decide to use the name ‘Twenty-Five Views of Worthing’?

Being interested in words I found this great fun. We talked about it at some length but nothing seemed to get everyone’s approval. I wanted a name that was a bit quirky and memorable. Prints by the Japanese artist Hokusai had become very popular in the UK, particularly the series ‘Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji’. This was the origin of the name Twenty-Five Views of Worthing. Bognor was too obvious, so I chose Worthing.

What sort of venues did you play? Would you recall some of those concerts and bands you played with?

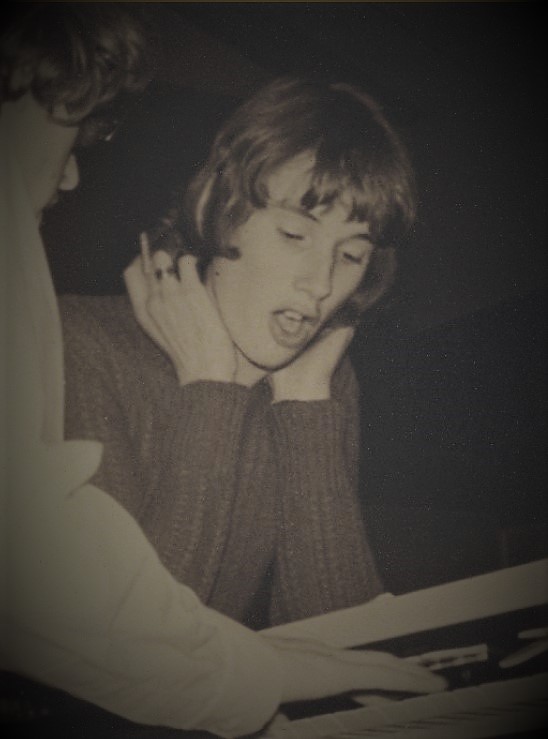

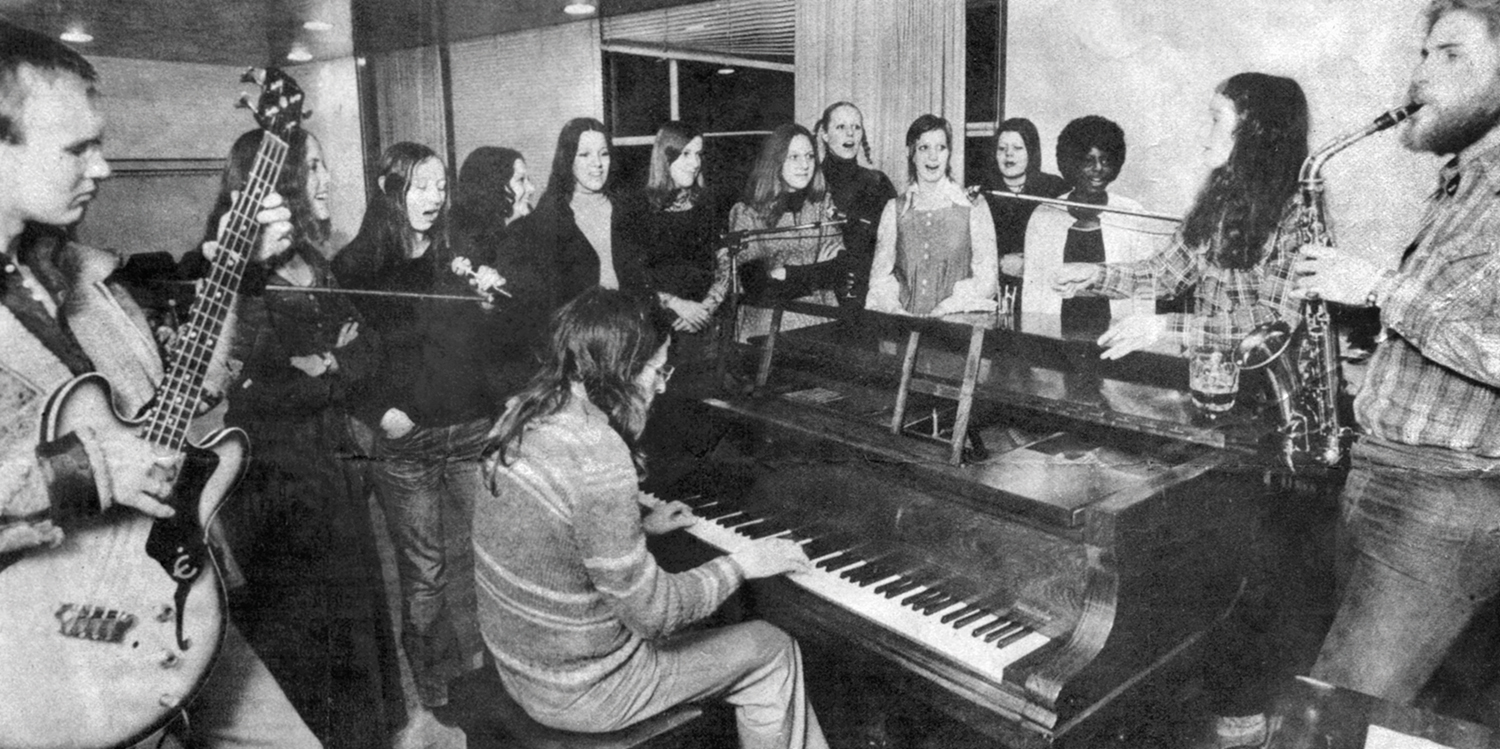

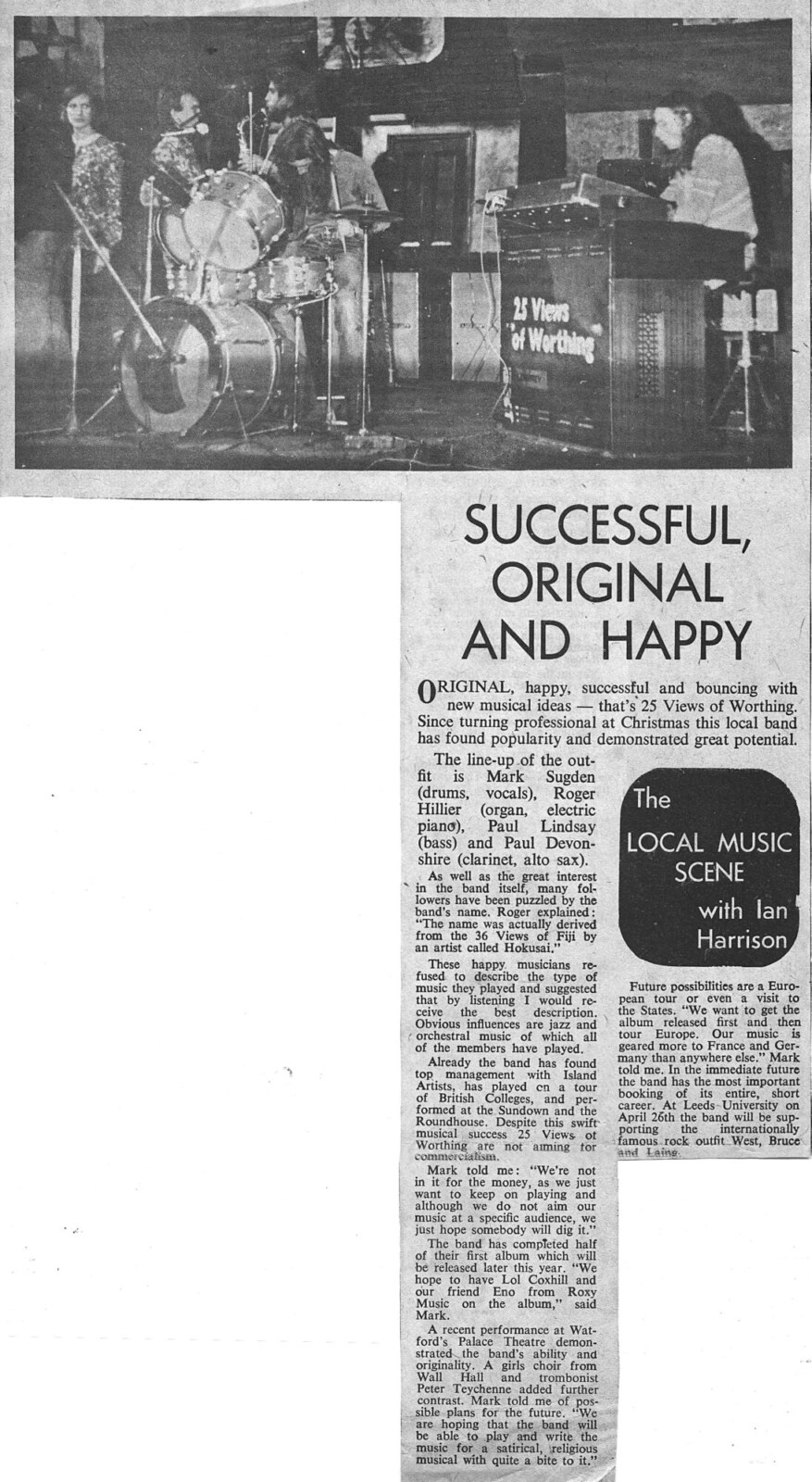

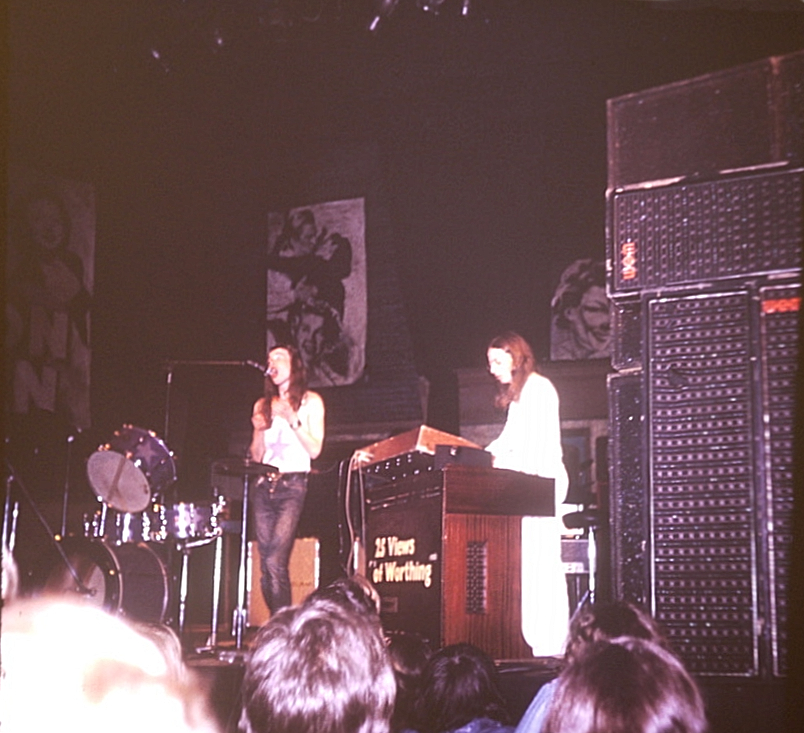

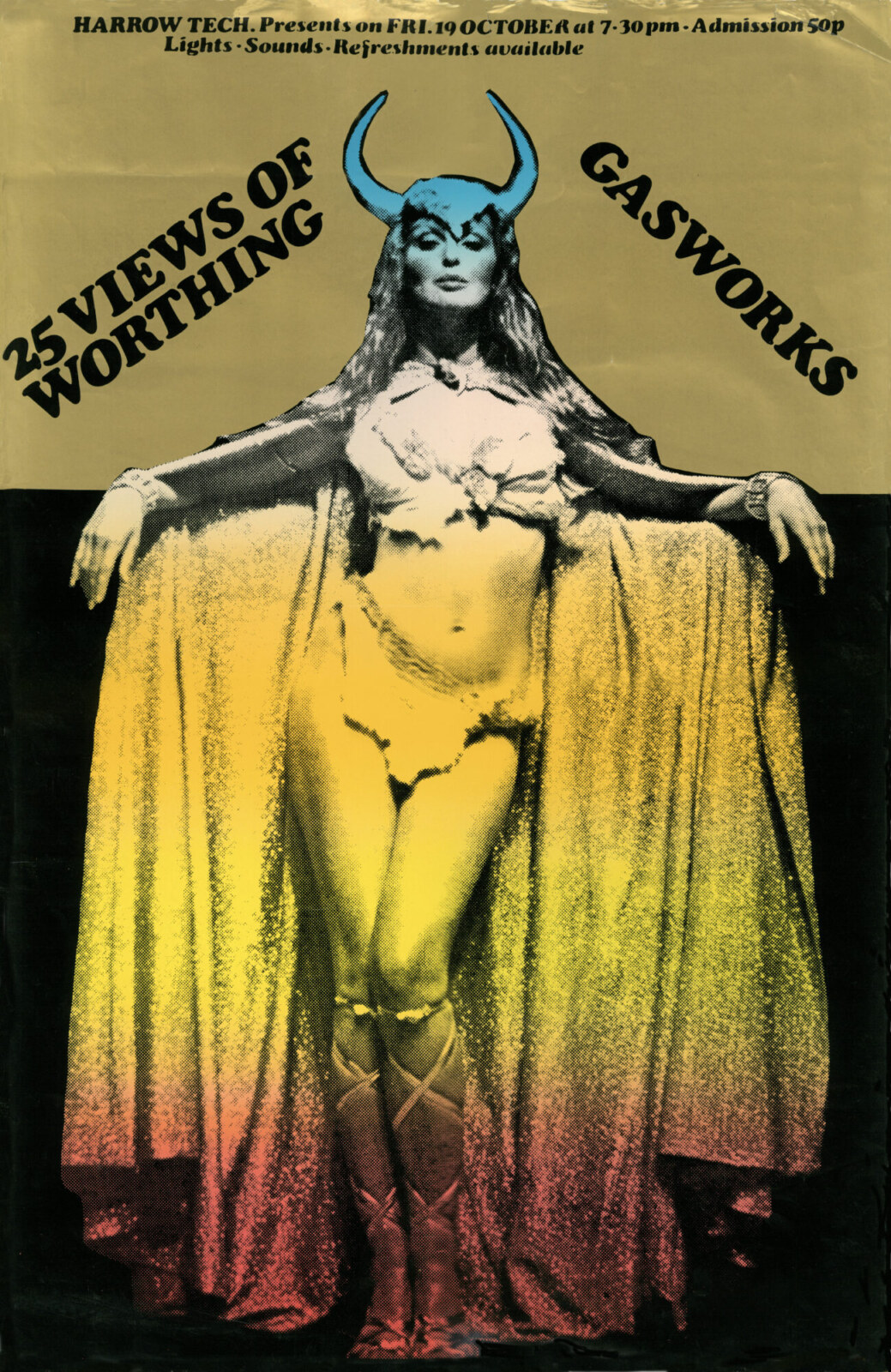

At that time, before it was mutilated by developers, planners, traffic engineers and the local council, Watford was a great place to live, particularly if you enjoyed live music. There were several music venues, from small halls like Kingham Hall, where we supported Argent, and the Trade Union Hall, where the Who appeared but we never did, to big spaces like the technical college, and the Town Hall (later renamed the Colosseum). Eventually we played Watford Palace Theatre, supporting East of Eden, and brought along the female choir who feature on the new album, as well as the trombone player Pete Teychenné, who later joined the band briefly in its transition period.

“Without doubt Soft Machine, around the time of their first two albums, was the biggest influence”

What influenced the band’s sound?

I should explain that Twenty-Five Views of Worthing had three distinct phases, with different line-ups. On the new album, we’ve called them Chapter 1 (1970—1973), Transition (1973), and Chapter 2 (1974—1977).

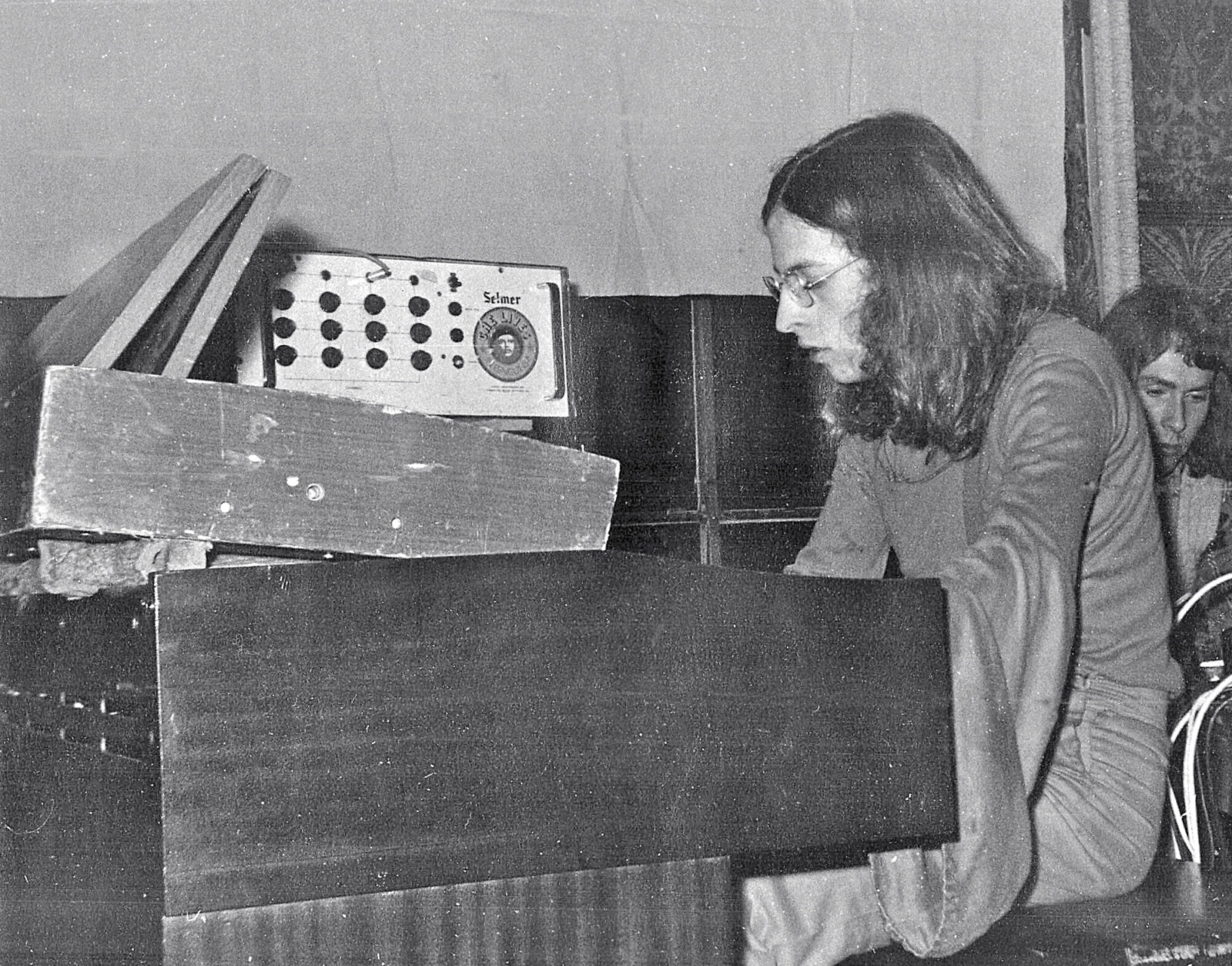

Without doubt Soft Machine, around the time of their first two albums, was the biggest influence on the sound of Chapter 1. Like Soft Machine we had no guitar, for example. However, saxophones and other wind instruments were important at every stage of the band’s development, and Paul Devonshire’s musical background brought along a strong flavour of jazz. Mark was keen that I should play the same instruments that Mike Ratledge used with Soft Machine, so I was kitted out with a Lowrey organ, and a Hohner Pianet that sat on top. Being a fan of Jimmy Smith, Graham Bond and Ian McLagan I would have preferred a Hammond, with a Leslie speaker cabinet, but I was happy enough with the Lowrey.

How did you get signed to a management deal with Island Artists in 1972?

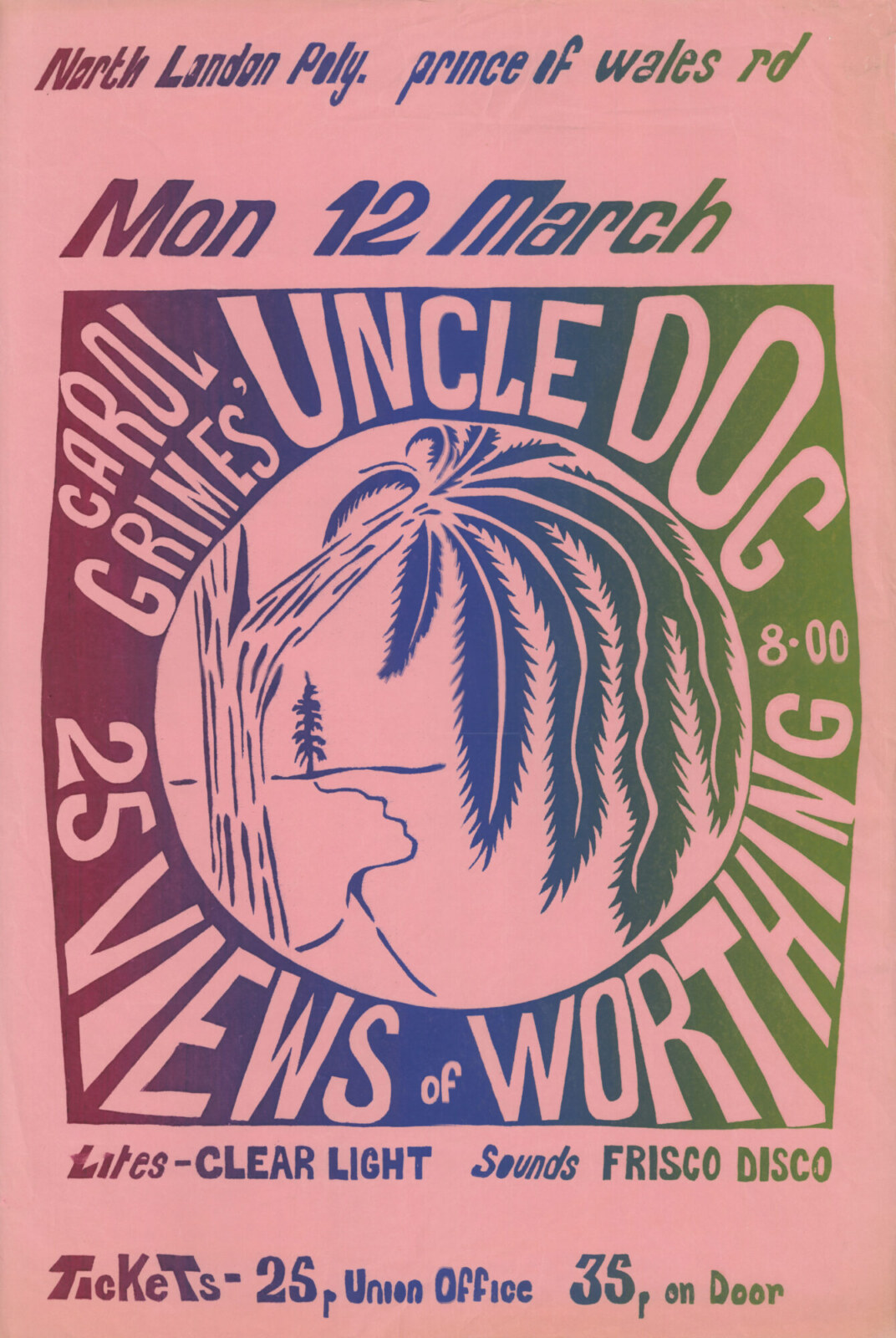

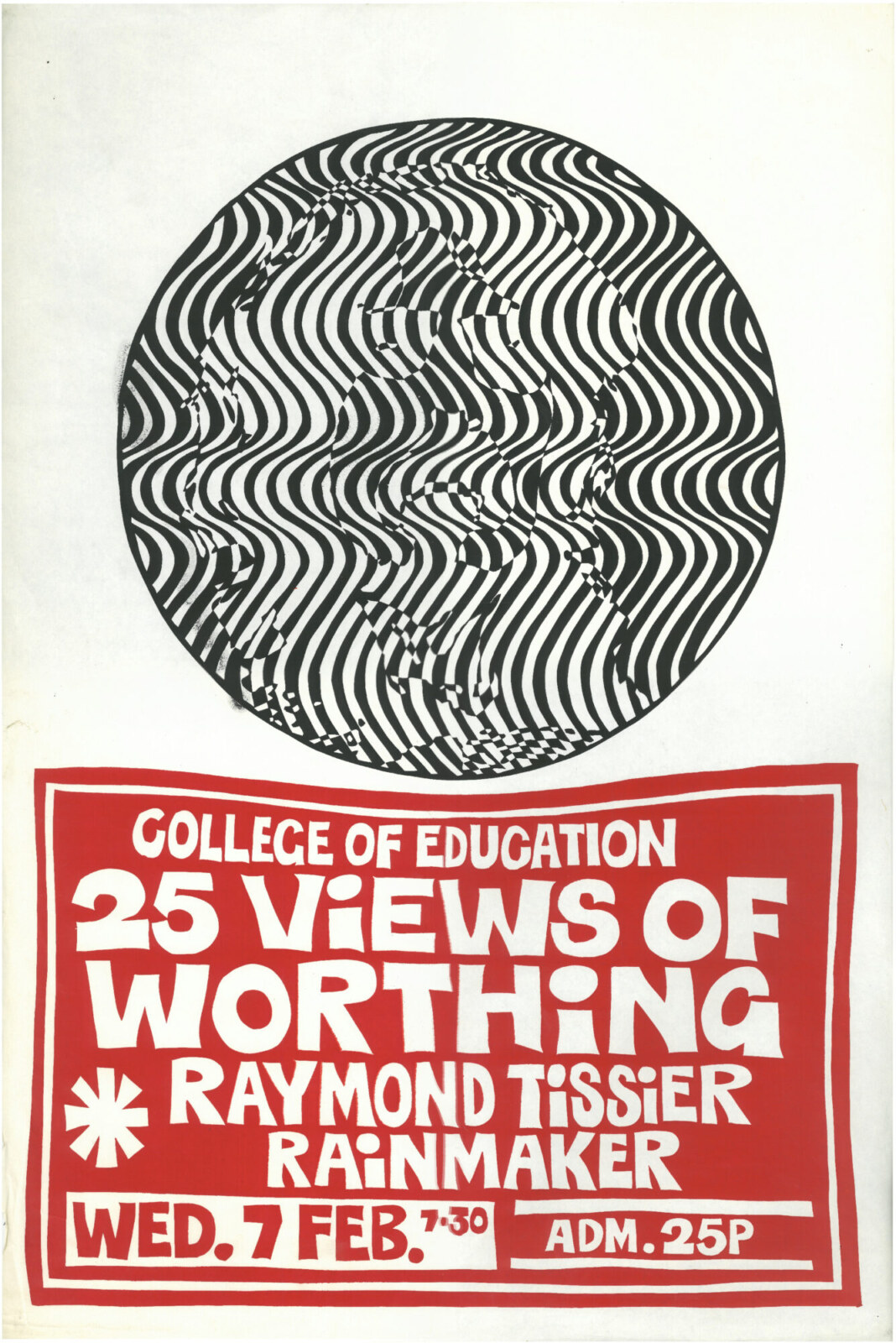

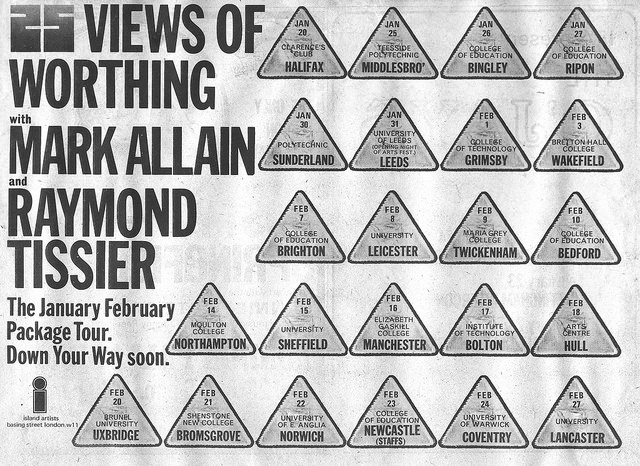

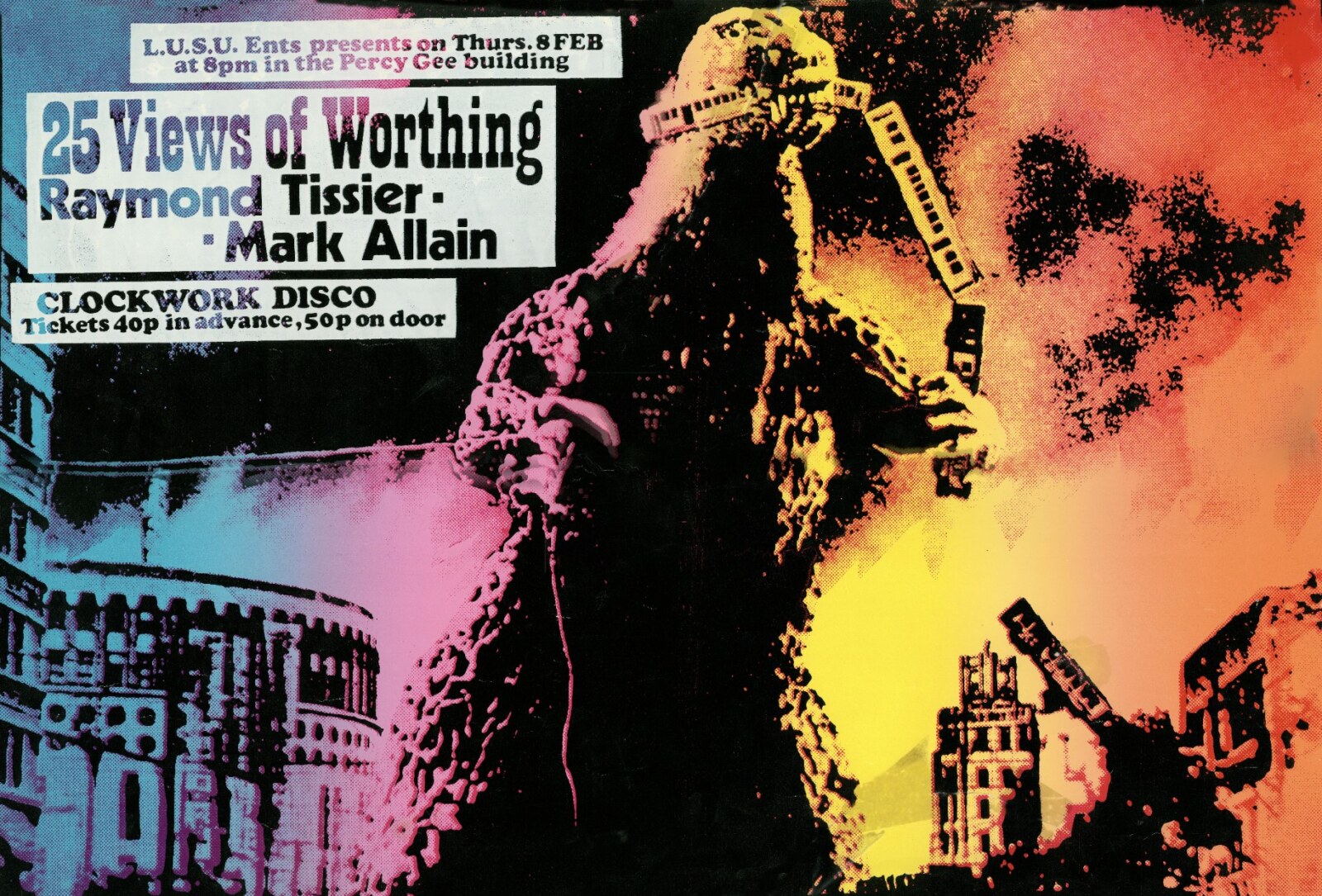

We organised a showcase gig at the Greyhound in Fulham Palace Road, and invited several record labels to come and hear us play. Island Artists was the obvious choice because we had been recording at the Island studios in Basing Street. Island Artists organised a tour of UK universities, colleges and other venues, advertised as a package of three newly-signed acts. The Worthings headlined, supported by Raymond Tissier, a solo singer/guitarist from the States, and Mark Allain and Roy Neave, a duo who also sang and played guitars.

What’s the story behind the recording? What kind of equipment did you use? Would you share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

In 1970, as Twenty-Five Views of Worthing began to take shape, I contacted Phill Brown. I hadn’t seen Phill for quite a while as he had been working in Canada. Now he was back in the UK, with a new job as an audio engineer at Island’s new studios in Basing Street, London. He had begun what turned out to be a hugely successful career recording the most well-known musicians in the business, as he describes in his autobiography ‘Are we still Rolling?’ (Tape Op Books, 2010). After our conversation Phill came to meet the band, and suggested we might record some music at Basing Street when the studio wasn’t being used by anyone else.

The Basing Street building was a converted church, with two studios equipped by Dick Swettenham, of Helios Electronics. Studio 1 was a large space occupying most of the ground floor, with a high ceiling as you’d expect in a church, and with an unusually long reverberation time for a rock studio. I think it was 1.5 seconds, which I liked a lot because, when we began to play, the space gave something back. I also liked the array of keyboards—a Steinway grand piano, Hammond, Mellotron, vibrophone and, this was a nice surprise, a small pipe organ with its pipes installed on top of the case. When played, each note had an attack that sounded as though the organ was taking a breath. In the basement was the much smaller Studio 2, which had a more conventional ‘dead’ acoustic. Both control rooms had a Helios console.

Throughout 1972/1973 we made a number of trips to Basing Street when there was some down time. Most of the tunes were recorded with the band playing together, each of us in our own screened-off space, to help Phill get a reasonably separated recording of each instrument on its own track. I think we could see one another over the screens, which was helpful for cues, etc. as there was often some improvisation going on. When we were happy with each tune, overdubs were recorded where needed.

This is where the fun started. We hired in yet more instruments, including a two-manual harpsichord and a huge gong. I thought I was in heaven, but things were about to go tits-up…

Why wasn’t the album released?

While we were busy recording what we hoped was going to be enough material for an album, there was a purge at Island and, along with a number of other acts, we were sacked. Effectively this sounded the death knell of the band as it was then, because it was no longer commercially viable.

In mid-1973 Paul Lindsay left the band and the first chapter of Twenty-Five Views of Worthing came to an end. We then recruited John Knox on bass and asked Pete Teychenné to join on trombone. Obviously this changed the overall sound of the band, and this can be heard on the album.

However, this transition phase of the band only lasted a short while. Paul Devonshire left and there was then a pause of about a year before the band reformed, with Paul Gillieron on sax, Harlan Cockburn on guitar and Malcolm Barrett on bass. Mark had met Paul G and Harlan when he was at Maidstone Art School, and they were both keen to bring new energy and ideas to the Worthings. Malcolm found us because he had heard we were looking for a bass player, and he too was welcomed to the new line-up.

This final phase is called Chapter 2 on the album, and was the version of the band that made a do-it-yourself 45 rpm EP, called 7”, in 1977.

How would you describe your sound?

I’m not sure I can—it’s hard to be objective when you’re deeply involved with something. Also, the three distinct versions of the band all sounded different. Chapter Two saw the most radical change, when Harlan joined and the band finally included a guitar. I think I’ll have to leave others to decide what it all sounded like.

What happened after the band stopped? Were you still in touch with other members? Is any member still involved with the music?

I’d built up quite a head of steam with the Worthings, and when the band came to an end there was no way I wanted to stop playing music. Working with Mark’s brother Ben, also a drummer, he and I put together two bands, one following the other. The first was called L’Age d’Or, formed around the singer/songwriter Chris Klein. This was followed by another band, which we named Interference. This time the singer/songwriter was Nick Williams, also known as Taff. Both bands had no guitarist but featured two keyboard players and a saxophonist. We worked hard, did lots of gigs, and kept the money earned to pay for studio time. We then made cassette tapes to get more gigs and, we hoped, a recording deal, but the deal never came.

At the same time, although we were no longer working together on our own project, Mark got me involved with several bands, including a pub rock outfit called JJ and the Flyers, fronted by Johnny Johnson, a charismatic singer, guitarist, and brilliant teller of jokes. One of his catch-phrases was, when introducing band members to the audience, “you can’t help liking him”, which applied to John himself, because everybody loved him.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

I loved playing to an audience, but I found touring tedious, and I was most happy in a recording studio. I can’t say I’m exactly proud of any music I’ve made, or helped to make, so I’ll just say that the music I’m most pleased with is usually what I’ve just been working on—at least until the novelty wears off.

‘Most memorable gig’ is a hard one for someone with a bad memory, but I’m going to choose the day I played on the back of a moving flat-bed lorry in Chesham carnival. It was a punk band hurriedly put together for the event, and named Pistol Day by Martin Harvey, who sang. Inevitably, vegetables and fruit were thrown at us by the crowd, and you could tell what sort of town Chesham was (and still is) because one of the band was hit by an avocado pear.

Are you excited by the recent Wind Waker Records reissue?

I’m very excited about the album release—it’s taken nearly 50 years to get there. It’s not something I was dwelling on throughout that time, but it was unfinished business—a piece of work that never came to fruition. I couldn’t have been happier when Austin Matthews from Wind Waker Records rescued the project, and I only wish Mark were here to share that joy, but at least he knew before he died in 2019 that the album was going to be released.

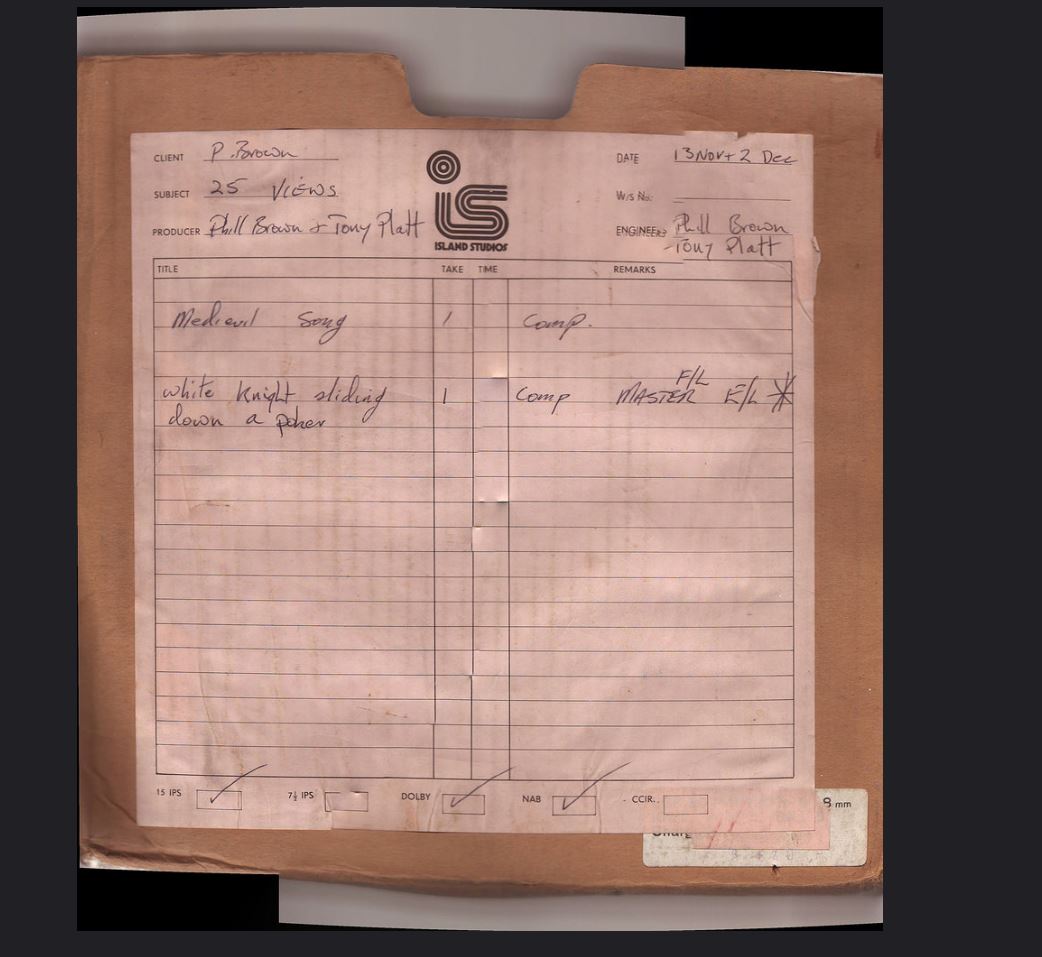

What was the creating process for it? What can you tell us about the mastering process?

Unfortunately the 16-track master tapes from Island had disappeared, but we had a very good stereo master on quarter-inch tape that Phill had rescued. We also had Phill’s recording, also on quarter-inch tape, of the only tune from the Transition phase of the Worthings, ‘In for a Quick One’.

This was recorded in a small hall at the back of the Sportsman, a pub in Croxley Green, using equipment brought along by Phill in a van, which he also used as a control room. With the 1977 recordings, there was no master tape at all, so we had to work from a mint copy of the 7” EP. All these recordings were expertly put together at Hiltongrove Mastering by David Blackman, and I’m pleased to say that Phill was there to approve the result.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thanks Klemen, and thanks very much for inviting me to let off some steam—I’ve enjoyed it.

Just a couple of things. We’ve had some very positive comments about the album, and most people have praised the graphics, so I’d like to mention my wife Caroline who, faced with a mountain of material, did such a great job on the design.

Finally, I want to say that making music has been some of the best fun I’ve had with my clothes on, particularly making music with other people. But—and this is going to sound po-faced, but I don’t care—a piece of music is a work of art and, like any work of art, it must be taken seriously. That’s when the real fun begins. Roger Hillier

Klemen Breznikar

Wind Waker Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram

Another interesting read, and an album to look out. Thanks

This is fascinating stuff. I saw both Primrose Path (originally PP to the Everlasting Bonfire) and 25 Views many times. I went to school with Mark Sugden in fact performed a puppet show with hin in about 1961!

I was in a band when I was 16 called Wrong Chemical which was named and managed by Martin Harvey. I remember Mark and Roger ( who I think played on a recording by us).It didn’t end well with Martin who was a seriously troubled soul, but I learnt a lot from that crew who introduced me to a lot of music and I have been making my living from music for most of my life. I found significant success with Asian Dub Foundation who I have been with since 1994 , made nine albums, toured the world many times and even topped the Official Uk Sales Chart at Xmas time with a track we did with comedian Stewart Lee. If any of you guys read this I would love to say hello to some of the inhabitants of Coombe Cottage like Phil Jones and Keith Clough. You can contact me at scsavale@yahoo.com. I still have the 25 views of Worthing 7″ somewhere!