‘Ocean’, A Lost Recording Of The Family Of Apostolic | John Townley | Interview

John Townley was a member of the folk-rock group The Magicians. After The Magicians, Townley built the first 12-track recording studio in New York, Apostolic Studios, which opened in 1967 and which was often used by Frank Zappa.

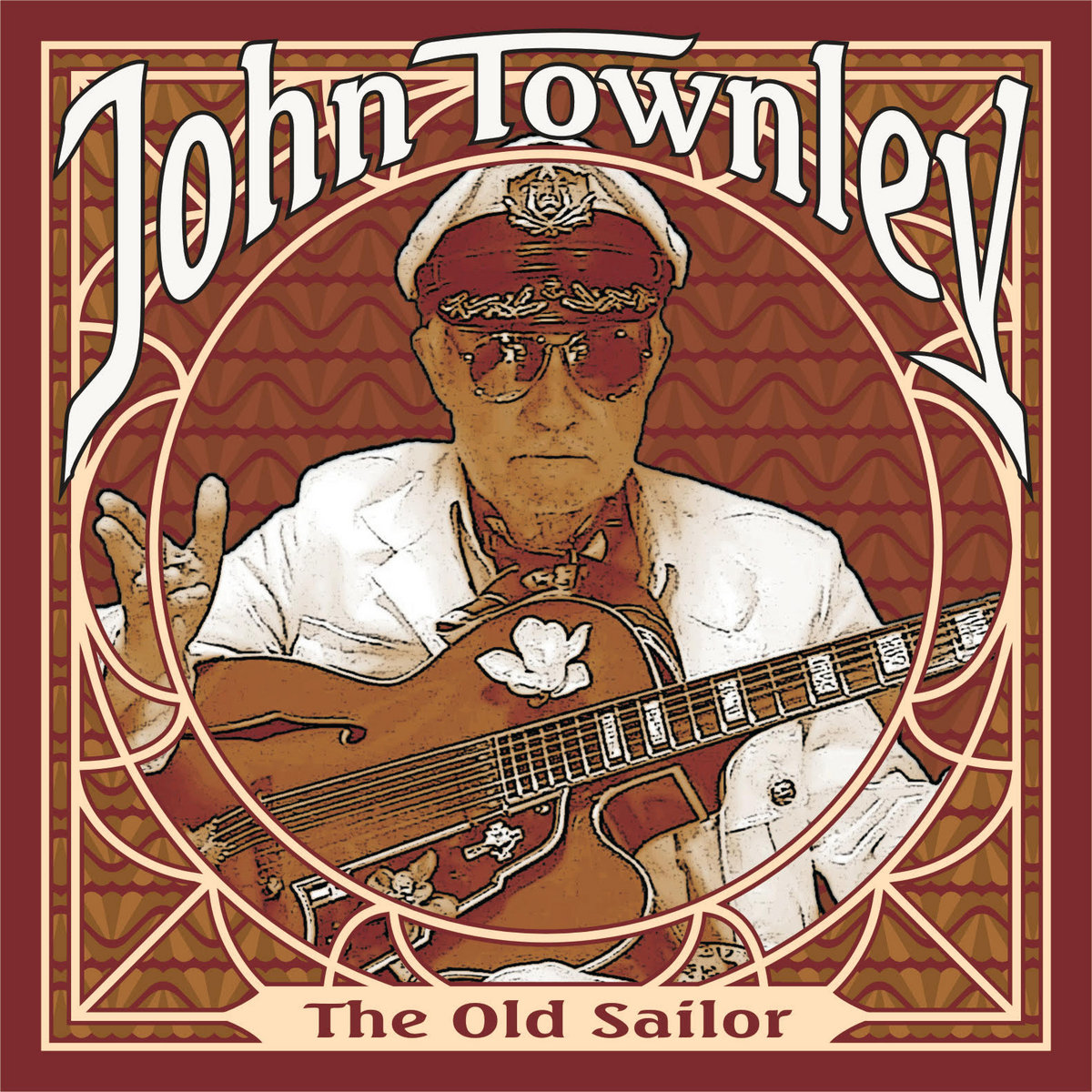

A naval historian, he is the founding president of the Confederate Naval Historical Society. He performs maritime music professionally and has recorded several albums in that genre. He has been part of several sea shanty bands, including the X-Seamen and The Press Gang. He is also a professional astrologer, has published eight books on the subject, and was a former president of the renowned Astrologers’ Guild of America. The material recorded in 1969 under the name of Ocean is a long lost psychedelic folk-rock gem!

“Everything goes back to the Rev. Gary Davis”

Lollipoppe Shoppe surprised me with the announcement of a lost recording by a group from the 60s named Ocean. Your album was recorded in 1969, but sadly remained unreleased until now. How did the label find you? I’m sure it was a bit unexpected?

John Townley: I had the album posted on my site AstroCoctail.com in the music section for years, and they just stumbled upon it, unexpected to say the least. It was the beginning of a wonderful relationship, part of that spin into a “new normality” that COVID-19 brought upon us all.

“We started playing mostly old-time tunes at very high volume”

Your first band was called The Psychedelic Rangers. It was a duo with David Blue and in 1965 you formed an all-electric folk-band.

To rearrange that. David and I were both doing solos in the “basket-houses” (where you passed the basket for contributions) and got together for a few months as a duet (I accompanied and harmonized on his songs). It was a meager living, and sometimes when there were only one or two in the audience, David would eat fire (a la a circus performer) to get some interest, until the fire department stopped it. After that, the next time I ran into him, he suggested that everybody was going electric (after Bob Dylan did), why didn’t I? So, I bought John Sebastian’s 1958 Les Paul (for $90, can you believe?) and that’s when I met Jay (who had just put a pickup on his fiddle) and Lyn, and together with gypsy Wayne (don’t recall his last name) on electrified paint can (small version of washtub bass) we started playing mostly old-time tunes at very high volume and natural Fender-amp distortion. That was the Psychedelic Rangers. Kind of Holy Modal Rounders (Steve Weber was my roommate) on steroids and electrified, before even they tried it. Curiously, unbeknownst to any of us then, another band was taking the same name at exactly the same time (spring-summer ’65) formed in LA, which later evolved to become The Doors. Seriality in action…would have made perfect sense to Paul Kammerer or later Rupert Sheldrake…

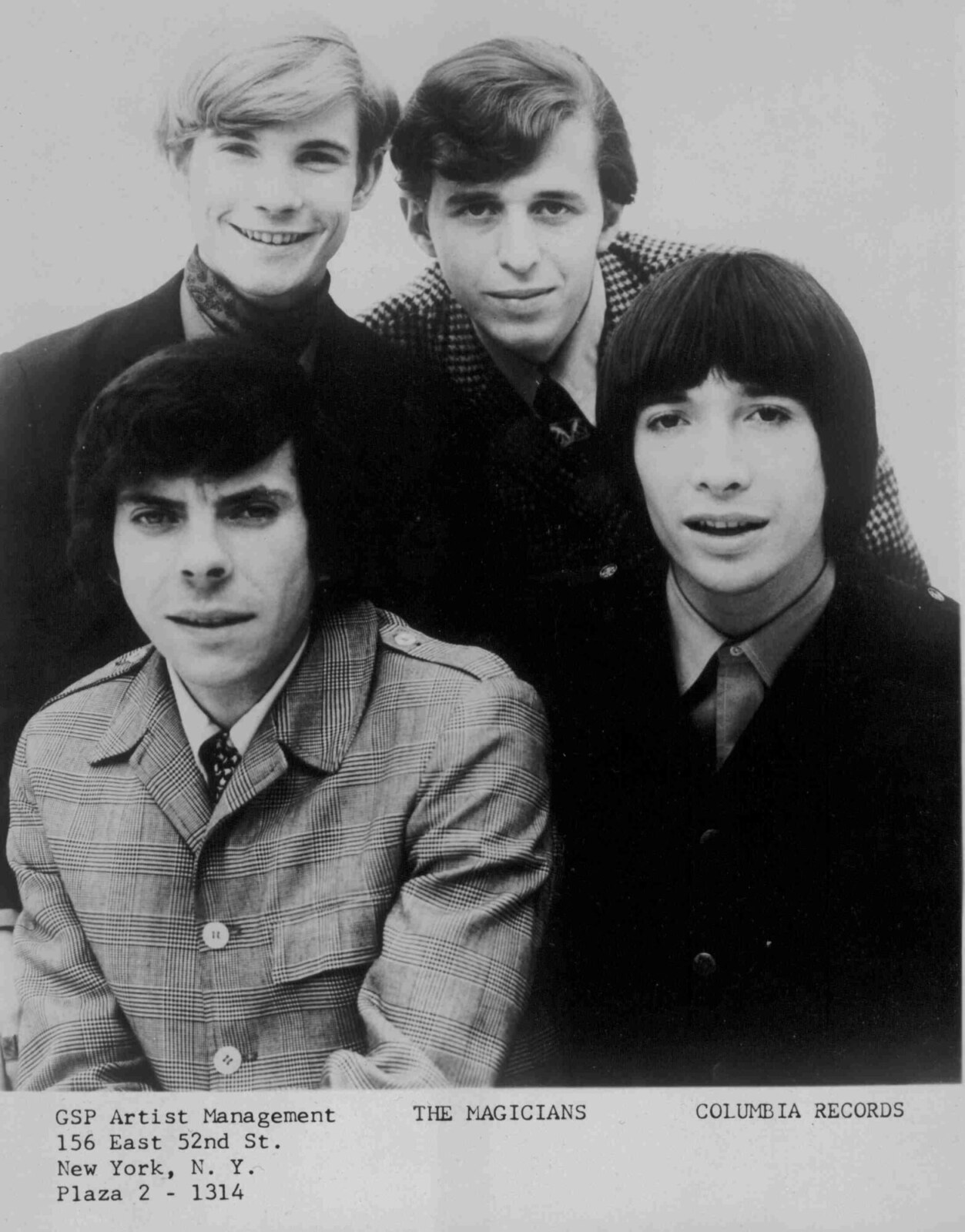

Then you joined The Magicians. You played guitar and managed to release four singles with Columbia Records. How did you get signed to a major label?

I was walking down MacDougal St. while still playing with Jay and Lyn and ran into another friend and denizen of the area, guitarist Allen “Jake” Jacobs. He said a group with an already-recorded single on Columbia had just lost two members and were looking for two guitarists to fill in, complete a B-side, would I like to come along and have a try at it? I did (there was no other competition) and we just fell into The Magicians, just the two of us doing the B-side (Blind Willie Johnson’s ‘The Rain Don’t Fall On Me No More’) which had been my signature (so far) acoustic solo tune. We were booked into the Night Owl (the group was managed by Koppelman and Rubin, who had signed The Lovin’ Spoonful ahead of us) and we subsequently went on to tour, record three more songs, and I played on several more after the group broke up in August ’66.

Was there a plan to release an album with The Magicians?

There was, and we went into the studio and just recorded live a lot of what we were doing on stage. Only years later was it all put into a retrospective by Sundazed.

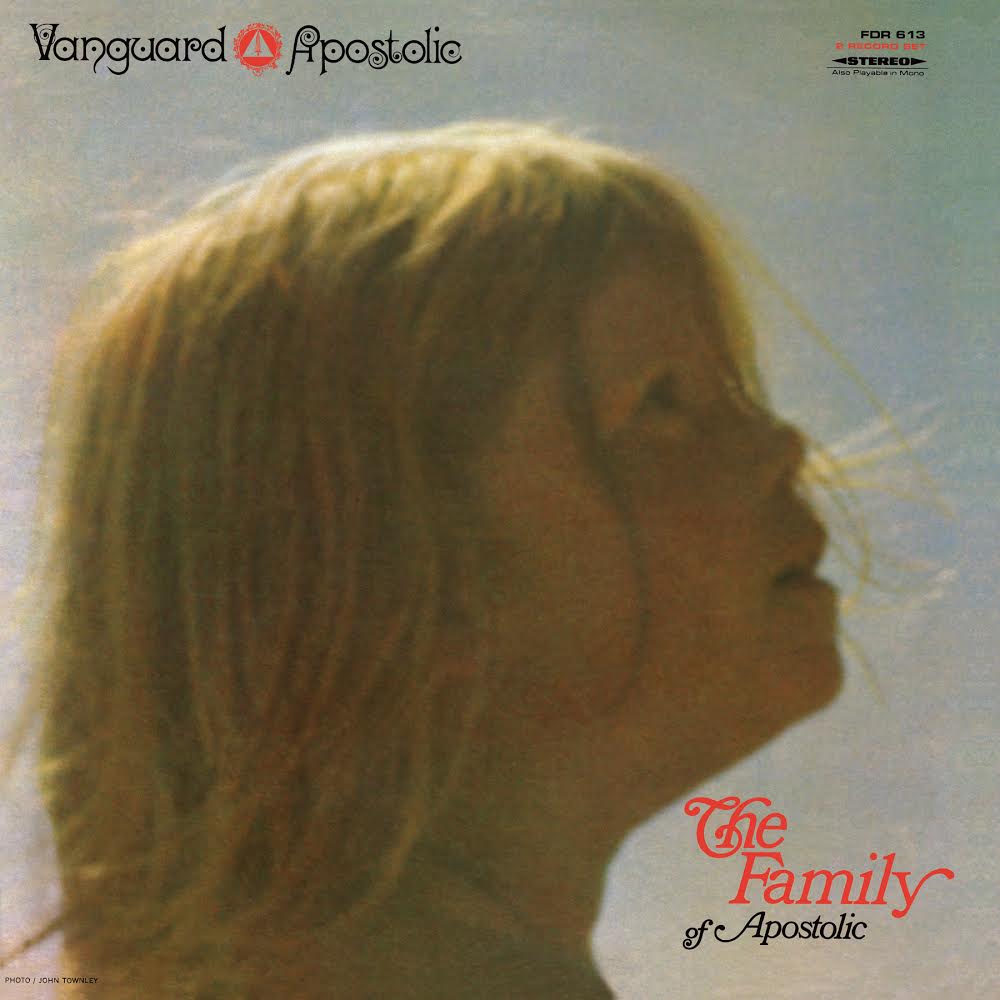

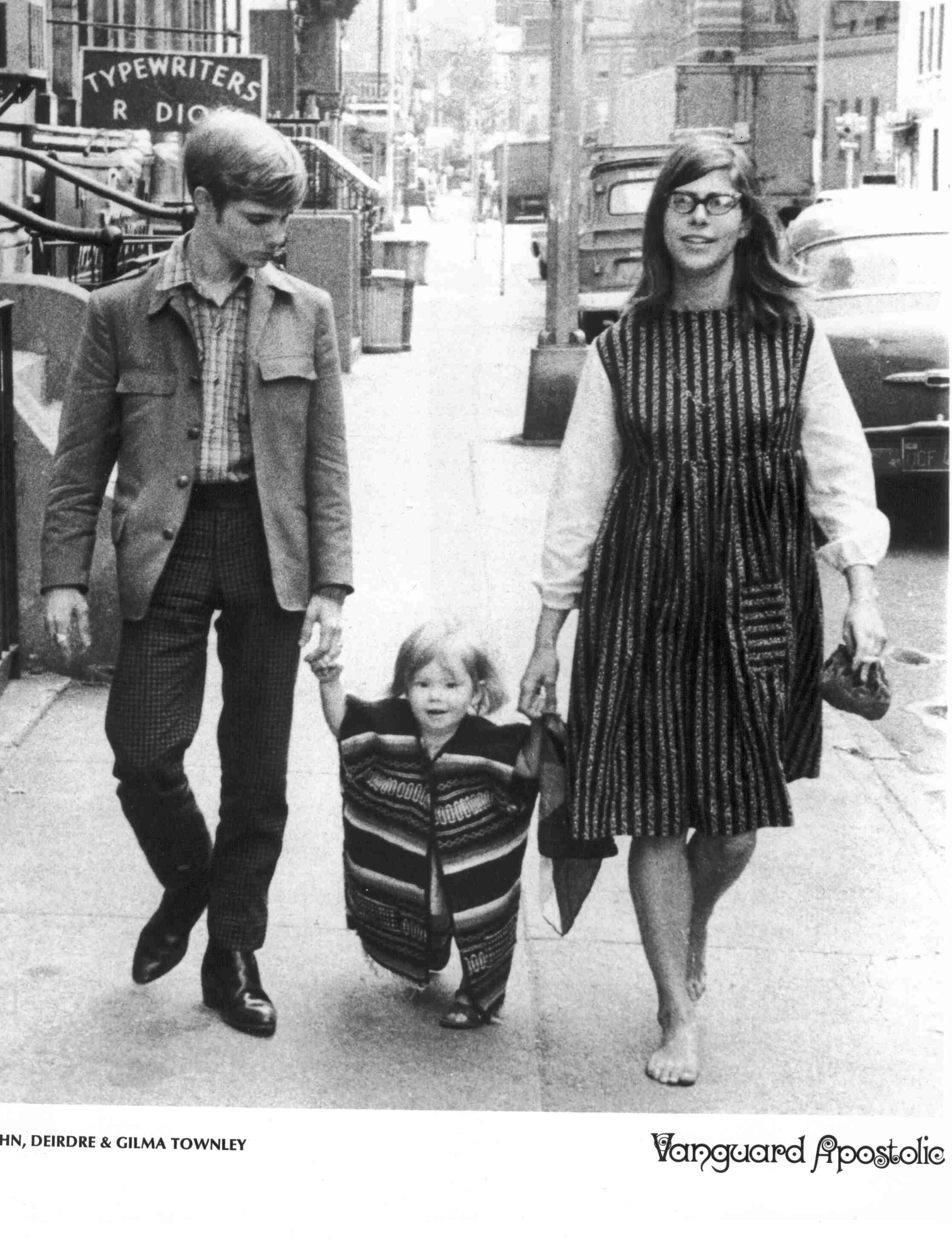

How did you meet Gilly? You married and played together in ‘The Family Of Apostolic’.

We met in Washington, DC, where I was playing at a folk club called The Open Way, in the summer of ’63 (found myself in the middle of the March for Jobs and Freedom there). She moved back up to New York with me, and it evolved from there, with various adventures there, to the West Coast, and back. Actually, we had separated by the time Apostolic was founded, but shared a daughter (Deirdre, the family album cover girl), and continued to compose, sing, and record together for the album, and to physically build the studio.

What can you recall from that wonderful double album?

A lot. But you could put it all together symbolically in the recording of ‘The Old Grey House’, because it symbolized the intended “extended family” nature of the whole Apostolic effort. It was written by Bob Berkowitz, for whom she had left our marriage, but then left him, after which we became friends – so there we were, an unlikely trio performing a song about their breakup (she on vocals, he on keyboard, me on drums). Following, superb sax player Travis Jenkins put on an wonderful instrumental overdub.

There were still spaces left in the mix, so newly-appointed engineer Randy Rand (whose wife Phoebe Stone did most of the studio’s elaborate artwork) took up the del-ruba (we had an orchestra full of multicultural instruments on supply) and did an amazing counterpoint to the sax solo. Doubly amazing because he didn’t really know the instrument, just picked it up and did it. That kind of mix-and-match, try-anything synergy of music and the heart were very much the calling card of Apostolic, how it was conceived, and how it was, in fact, delivered.

That album was released on Vanguard Apostolic, a short-lived record label produced from a collaboration between Vanguard Records and you.

We were looking for a distribution deal for our own productions, and I had run across Maynard Solomon at Vanguard before. Essentially, there were only two folk record companies that took the recording part seriously – Vanguard and Elektra – and I knew Vanguard better, so approached Maynard Solomon, and we struck a deal where we’d have a label name but they’d do physical production, pressing, and distribution of the LPs themselves. Basically, we would hand them a final master, artwork ready to reproduce, and take it from there.

Having come from larger-label experience, I didn’t trust their ability to get airplay the way Columbia could, so I formed my own promo network from the bottom up, headed by Magicians fan-club members across the U.S. who plastered posters up in high-school hallways and even bathrooms, badgered local DJs, generally screamed for attention, and the Cleveland division actually got ‘Witchi-Tai-To’ to break into the top ten there, then on to the rest of the country. Vanguard never did get a hit single on their own until Joan Baez had an off-her-album fluke with ‘The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down’ in 1971 (and they had had her in their stable since 1960).

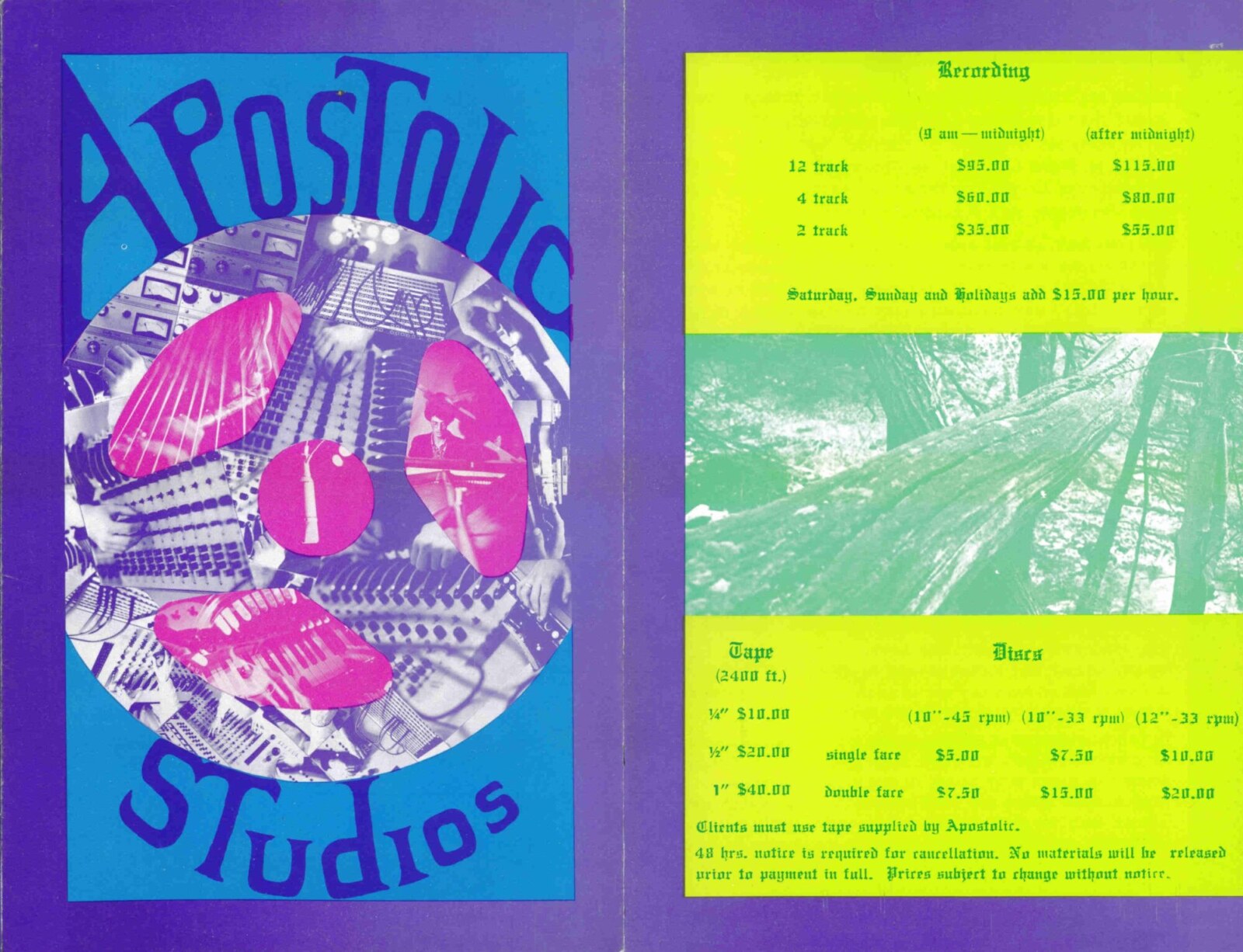

What can you tell us about the formation of your own Apostolic Studios?

It came from the Magicians recording with Roy Halley at Columbia. Terrific engineer, very restricting studio. It was uptown in the music biz area (all the musicians lived downtown in the Village), it was brightly-lit with walls of dirty white pegboard, it was a union shop so you couldn’t touch the board yourself. Even Roy couldn’t touch the recording machines, each had a separate union engineer in charge…so if you had a tape echo going on on a two-track (conveniently in another room!), a take would start with Roy saying “Take one”, followed by “Take one, rolling!” in the next room, then “Take one, rolling” on the eight-track in the same room, and then you knew you could start playing, It was like being on a submarine-movie torpedo launching …and, of course, you had only eight tracks, big for the time but clearly not big enough. The release of the eight-track breakdown of ‘Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band’ shows how clever you have to be to manage with only eight. And, their cue system demanded you hear the engineer’s mix only, there was no adjustable performers’ cue system.

Clearly I would be happier downtown, with a nice ambience (where you could choose your drug of choice and lighting for it), a bigger multitrack, and no producer or engineering restrictions. Someplace where you could sit down and compose with the studio as an instrument, rather than just record your live act and add a little to it. The only person who had ever come close to that concept, but only on a personal and limited basis, was Les Paul, and no one had expanded on it.

It was the first 12-track recording studio in New York. How did you get the idea to create a new studio? Was it difficult to gather all the necessary equipment?

I came into a small inheritance from a great aunt when I turned twenty-one (August ’66) and had these ideas brewing, so I quit the Magicians and launched into trying to make it happen. I knew I didn’t have enough money, but after a set of visions really set me straight about everything in life (see here — yes, this was psychedelic music, but not the rambling West Coast version, more like The Holy Modal Rounders, whom Wikipedia now credits as the beginners of the style). I just went ahead and trusted in fate.

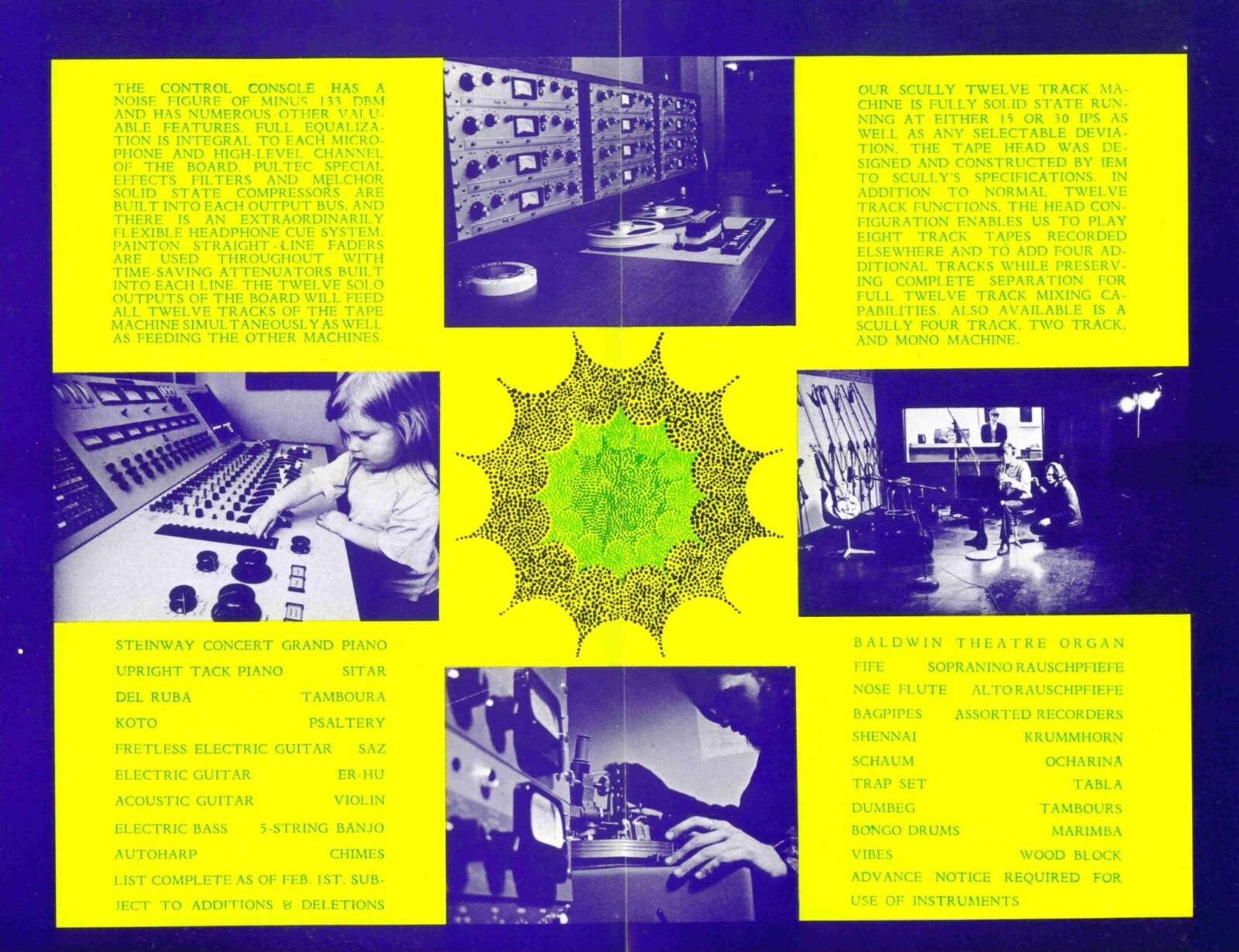

I got a reference from audiophile-writer Ivan Berger (a friend of friend Ana Perez who was then harboring her then-unknown cousin of Jose Feliciano in her Lower East Side apartment) for board-builder Lou Lindauer who became general advisor on the whole operation. It was me and my friends, whoever wanted to help, none of whom knew anything about building, wiring, but were eager learners – from Lou we learned carpentry, wiring, plumbing, all the nuts and bolts of construction, one mistake at a time. Approaching Scully early on, it was clear I couldn’t afford a 2” 16-track machine, so I had to go with 12-track on 1”. That turned out highly fortuitous, as 2” tape was very expensive, people were reluctant to go there even when it became a standard, but 1” was cheaper, and if you had an 8-track master that you wanted to do more with, you could actually add four more tracks, because of the way our heads were aligned. That was much of our initial business.

So, Lou built the board (D&L Processing, his company), we had Scully special-built 12-track and 2-track. The board had fancy UK Painton faders (all anyone else had was big black knobs). Importantly, it had a separate performers’ cue system, so you could hear the mix you needed to do a good overdub. In addition to a plate reverb, we had a six-story stairwell live reverb set up (like Columbia and others). And, it was downtown on 10th St at the border of the East and West Village, and it was stage-lit so you could have any mood you wanted, whatever your chemical of choice. Speakers were sets of KLH-6s (which we regularly blew out, small home-made repros of Bose, and later two Altec-Lansing VOTT speakers. Melchor compressors, can’t think what else.

Though laughed at by the regular music biz for its location, complexity, and non-standard appearance it succeeded quickly. Indeed, the brother of a Playboy bunny friend from Magicians days came in and saw it, and months later went out and replicated it (same board, same Scully 12) just a few blocks away, called it The Record Plant. Following that, Jimi Hendrix opened a multitrack on 8th St., and it had evolved into a standard setup. It was my dream, and almost any studio I use to this day is a grandchild of its unique innovations, now taken for granted.

Since I didn’t have enough money, I lucked into some partners who did, and who then found more, until at the end we were filing to go public with the operation (which then included Pacific High Studios in San Francisco, another source of tales). But the quick recession of the early ‘70s put an end to everything, and that was that. A dream brought to reality, and now inherited by everyone, public domain.

For a whole article on the studio hardware and history, see here.

You collaborated with some really well known musicians such as Frank Zappa, The Grateful Dead, Sonny Sharrock, Larry Coryell, The Fugs and many others. What was the scene back then in New York and what do you recall from working with mentioned musicians?

Well, most of them recorded at Apostolic, but that doesn’t mean I worked with them musically. Certainly Frank and the Mothers were friends/acquaintances and were in and out every day. We produced Larry (he harmonized the song, and was the group’s guitarist on ‘Witchi-Tai-To’), I even managed him briefly, a brilliant guitarist with a beautiful but difficult wife), and of course Steve Weber (of the Fugs, later The Holy Modal Rounders) was my off-and-on roommate for years. There were so many astonishingly-bright lights all wandering about and playing with each other that were just hanging around the studio (like Buzzy Feiten – came in one day on acid and started playing spontaneous and blistering rock lead figures in graduating tone rows! Well, he did go to Mannes…) .

But there were so many currents of music and culture all mixing and matching selectively, some you knew, others you just passed on the street. I was repeatedly mistaken for Andy Warhol, but only knew his people and scene (just down the street) second-hand through underground filmmakers.

Steve Weber recently passed.

I was sorry to see him go…he was not well for years, squirreled away in the Virginia countryside…spoke to him once on the phone from here, first thing he did was ask me for some Vicodin (actually for pain, in this instance) but I could not supply it. The Rounders were an integral part of my life…even to the extent that before they formed, the one act my parents and I (still in school) saw when we visited the Village was Stampfel doing a solo act with banjo. The very same banjo (Paramount C style) I later found in a pawn shop (Peter had sold it) and recorded on the Family album, and Rev. Davis recorded on it, too. Steve lived with me part-time in my second place in the Village (St. Marks Place) and then later had my basement (a two-story railroad flat) on 10th St. during the studio days. He and his wife Lark (a North Shore Long Islander) and Gilly and me spent a lot of time together. I remember tuning in the late night show on WBAI and finding Rev. Davis was on, so Steve and I raced up to the radio studio to join him.

What was the usual process in the studio?

Depended on who you were. Clients we didn’t know came in and booked time like a regular studio, recorded and paid, and left. Those who were friends or friends of friends would just come in when a spot was open and put something down, see what developed. It’s how we discovered the artists we produced, and just how we lived from day to day. Very non-linear.

Your wife has performed on works of Frank Zappa during the period she was at Apostolic Studios.

That was an accident of the moment. She happened to be in the entry room with close friend Becky Wentworth (also from the original ’63 DC crowd) and Frank just pulled her in, along with engineer John Kilgore and some Mothers, stuck them into the grand piano with the pedal down, and let them improvise. Everyone had a good laugh at it, but now it appears to be legendary history of some sort…

What’s the story behind ‘Ocean’ recordings?

It was intended to be a performance-ready version of The Apostolic Family, composed of Jay, and Lyn, Peter, and me (all on the original album plus drummer Jim Willis, but it really turned into a Jay-and-Lyn album as he was writing prolifically and they were a duet live. With a compelling voice like hers, and brilliant fiddling like his, what else could you do but feature both? So, it became Ocean instead of another Apostolic Family, but various needs to travel separately for other things, including Jay having a paying offer to perform with Cat Mother and The All Night Newsboys, and shifting personal issues caused it to disassemble. And because Apostolic itself was on the way to disassembling, the final masters got scooped up it its last days, but fortunately I had kept a mono reference copy, to appear decades forty years later on AstroCocktail, now on Lollipoppe.

The album was recorded in the summer of 1969.

It was a chaotic summer. My next wife-to-be Christine (Magicians fan who led Cleveland promo of ‘Witchi-Tai-To’) arrived, with a pistol-waving father in hot pursuit. When Ocean just finished the album, she went off with some of them to the Woodstock. I, at the same time, was stuck in Vera Cruz, Mexico to get a better solar return (why and wherefore here), for ten days because there were no flights out. In the meantime, half of Ocean had tripped out to Canada, where they bought a car on my American Express card, and subsequently came back and broke up.

What can you tell us about the mastering process?

It was mastered by John Kilgore (of the Zappa session!), who has garnered two Grammies since leaving Apostolic, and not messed-with to update the sound (although some suggested it). It was treated like an historical recording, and just brought up to clear reproduction levels for CD and LP.

Why wasn’t the album released?

No one buying…recession was starting to happen, styles were changing, and the record biz was in flux. Vanguard wasn’t eager to do new releases, though a deal had been struck with Atlantic for more Coryell-related releases, to which they didn’t live up (promised promo, didn’t do it, so the record failed, and they picked up the artist after), also helping to doom the over-indebted studio.

Was there a certain concept behind the album?

None. Just do what we all thought sounded nice. Not sure who came up with the title, nothing maritime related…

“Crazy, electrified old-timey”

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded?

Some are specific, like the little talk-over ragtime piece, which was literally variations on a Rev. Gary Davis guitar piece, which he gave various names to including ‘Slow Drag’ and ‘Stovepipe Rag’.

Others were more culturally inspired, like ‘Rampe’, which I thought Jay had learned from his Turkish family background, but later learned he actually got from Peter. We had been doing things with Middle-Eastern and Pakistani (‘Dholak Gheet’) influences already, and this was just another, in 9/8 – though curiously not the style of 9/8 as is normally done in the Levant, more like a directly-to-rock approach to the tempo like Brubeck did with similar odd-tempo pieces in jazz. Over there, it’s a fairly relaxed feel and you don’t even notice the time signature, where here it’s crazy and manic and jumps the beat. I’ve since written an English-lyric version with both verse and chorus (Ocean did only the chorus), equally as breathless, hopefully on my next effort.

‘Reuben’s Train’ hearkened back to the way we did ‘Fiddler-a-Dram’ on the ‘Family’ album, which was literally how the Psychedelic Rangers did it. Crazy, electrified old-timey. I can’t tell you how influential the Rounders were on us all…sadly, when they expanded and went electric (mostly at Stampfel’s instigation) they lost the centered feel and just dissolved. Their original balance was Steve’s anchored rhythms and strangified lyrics holding down Peter’s off-key madness. They were a stoner’s dream to watch, as they could pause suddenly in a song, and then come down on some precise but totally-unexpected beat that would completely blow you away. You thought you were on a random flight, then suddenly pulled back into the beat by the seat of your pants, quite amazing.

Did the group play any gigs?

No, never that I recall, things changed so quickly after we finished recording. I did put together an actual post-Apostolic band with David and Genie Ames (also on the ‘Family’ album) that did gigs, even got a nice NY Times review right after Ocean drained away. We never did an album, no studio left to do it in…

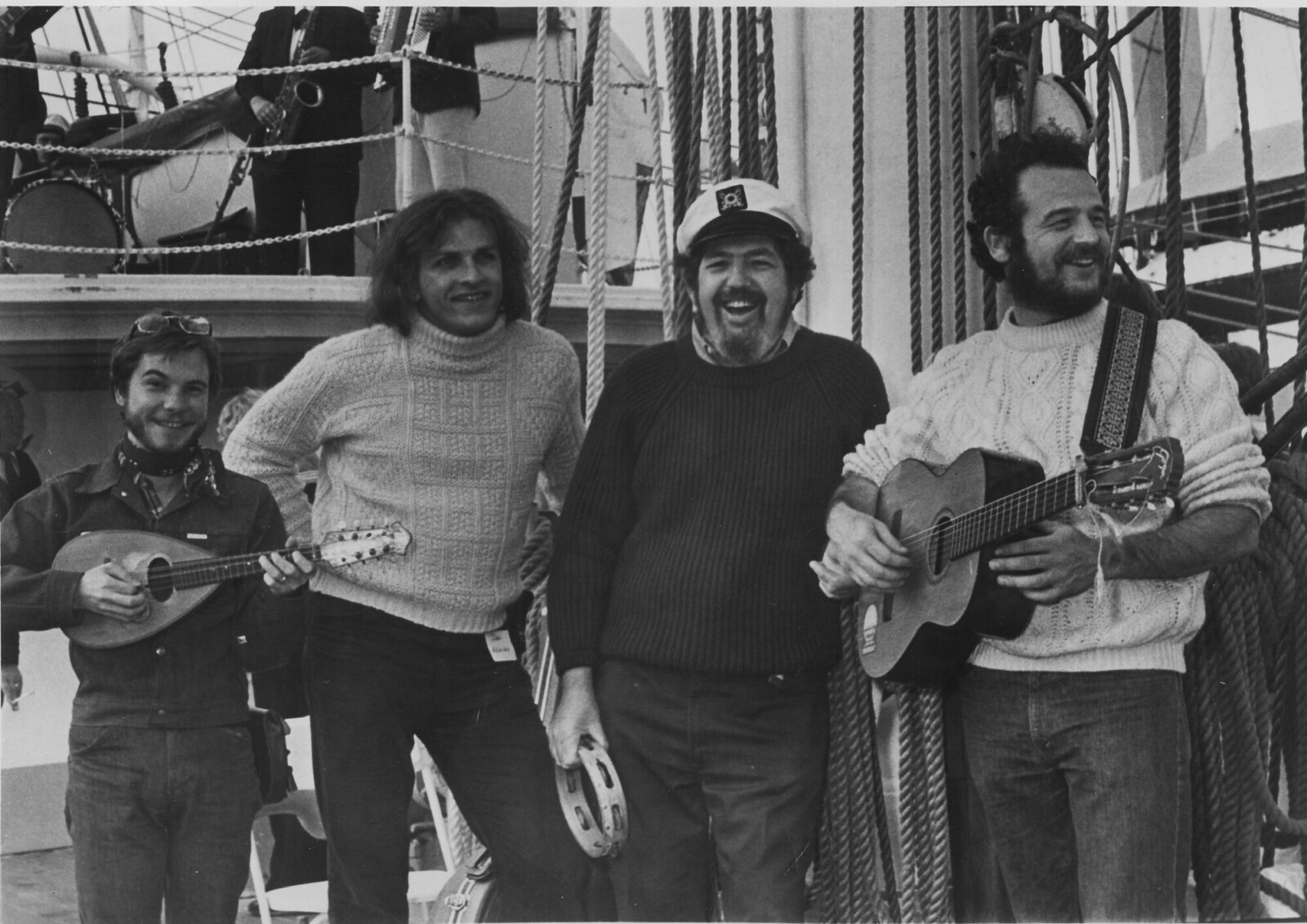

What about The X-Seamen’s Institute?

After falling out of the pop music business (including post-Apostolic gigs as salaried songwriter for MCA, CBS, and Buddha) I went to work as an editor (first at sex-crime tabloid The Inside News by publisher Bob Harrison, of Confidential fame, then Sexology Today, a more legit medical/psychological monthly). Too many funny tales there to get into here, but for something musical to do I happened on to regular sea music sings at South Street Seaport being led by Bernie Klay and Frank Woerner.

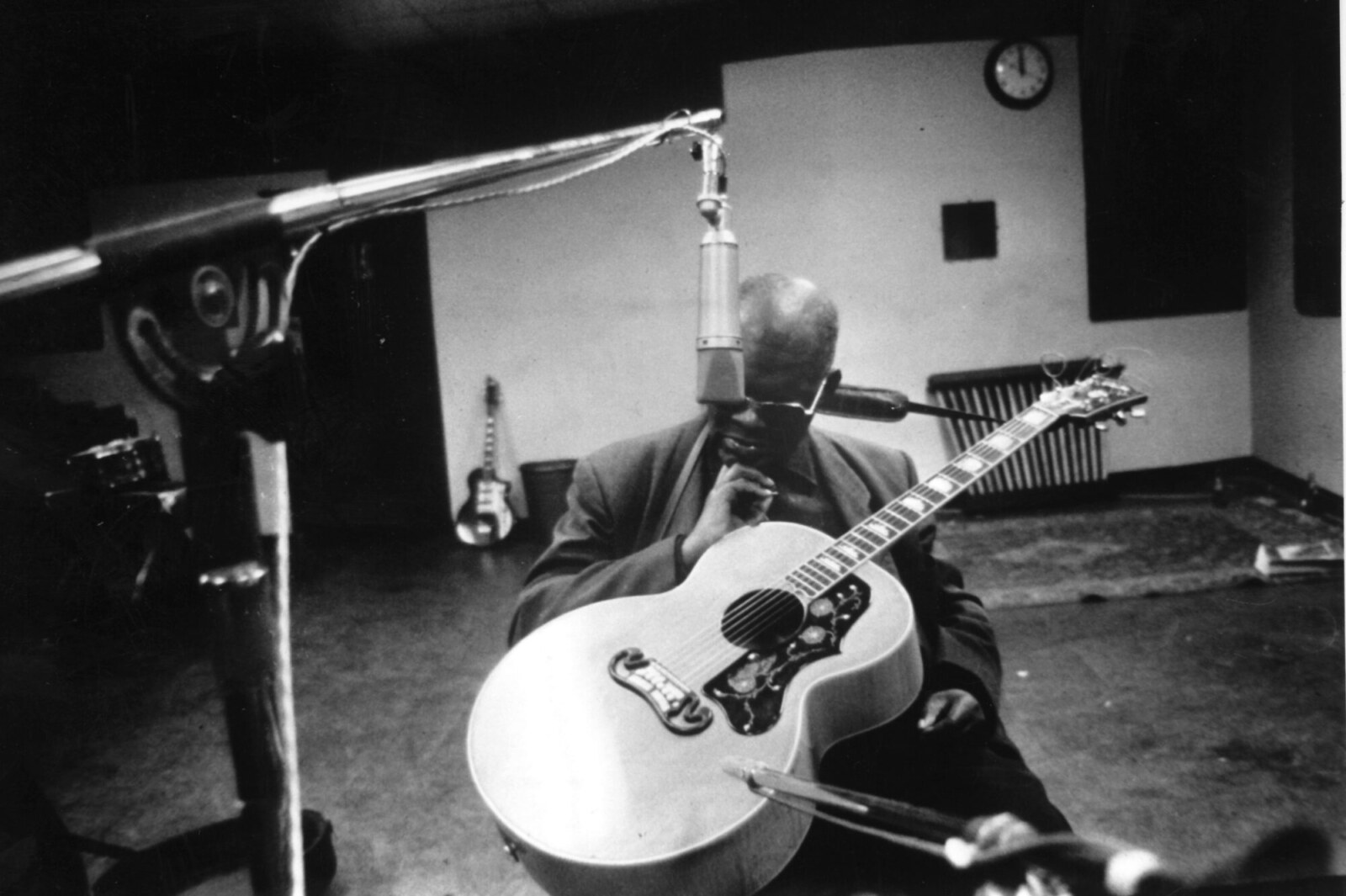

They were inspired and inspiring, but also rather off-beat and off-key, so I and another solid player Dan Aguiar joined with them and together we became The X Seamen’s Institute (named after the Seaman’s Institute nearby). The band had a large following at weekly concerts for ten years, because everyone participated and had a rousing good time. But a live recording always turned out too raw to accept, so I took them into a four-track studio with another engineer from Apostolic (David Baker) and made a recording that “sounded” live but wasn’t, with selective overdubs and editing, like I did with Rev. Gary Davis’s ‘Apostolic’ album.

Amazingly, the Smithsonian Institute picked up those recordings long after and I still get modest royalties today, expect more with the Tik-Tok shanty craze going on…

That became sort of a folk recording protocol, and the X did three albums that way for Folkways, and I produced two tall ship festival albums with multiple artists for Folkways as well (Sea Songs Seattle and Newport Tall Ships Shanty Festival). Also two albums of The Starboard List and another of the Celtic group Flying Cloud for Adelphi. If there was anything I contributed in Apostolic fashion in the sea-folk realm was to studio-ize folk music recordings to smooth and enlarge them, something which had been previously anathema in folk circles.

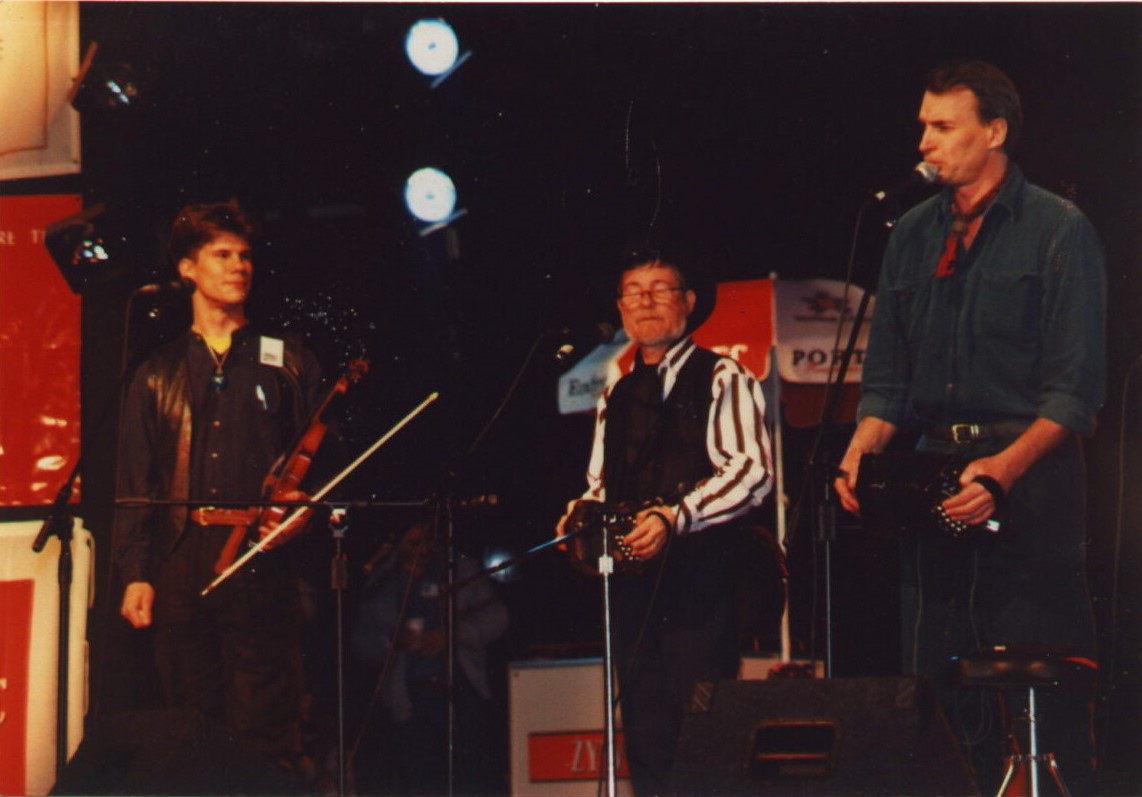

And, in the mid-‘70s, also got together with Jay and Lyn again for two National Geographic albums (‘Songs of ’76’ and ‘Songs of the Civil War’). In the same vein, I accompanied Oscar Brand on his recording for the Bicentennial, and dissatisfied with his historical selections (mostly political, as if that’s really what people were mostly singing in the late 18th Century) decided to research my own, which turned into ‘The Top Hits of 1776’ for Adelphi, with Jay again on the fiddle.

Mainly, in that decade, I returned to folk music, began specializing in maritime, adding pop music derived recording to the mix.

In 1991 you released ‘Sailor!’ and ‘A Chesapeake Sailor’s Companion’ followed in 2000. You currently have a brand new album out, ‘The Old Sailor’. Would you like to present it to our readers?

Actually, ‘Chesapeake’ was recorded in the mid-‘80s for The Mariners’ Museum by Adelphi, as I was by then living and working (for that museum) in Virginia, so wanted to do an historical LP for them, and the CD version came in 2000. The Press Gang, comprised of various Virginia-based friends and Cleveland-born wife Christine, even including Charles O’Hegarty at one point, were performing around the U.S. and Europe through most of that period.

‘Sailor!’ was done in a several-day lark in Liverpool, on one of my first post-Press Gang solo tours of Poland and the UK. In twenty-four hours of recording time, sang and played the whole thing myself, the logical result of Apostolic’s heritage. Just as it was Bing Crosby who discovered the microphone was a vocal instrument in itself, not just a recording device, so Apostolic introduced the same role for the studio, with Zappa very much in the forefront of developing the concept. Now it’s just assumed that you can sit down in the studio and create everything from the very stuff of that environment itself.

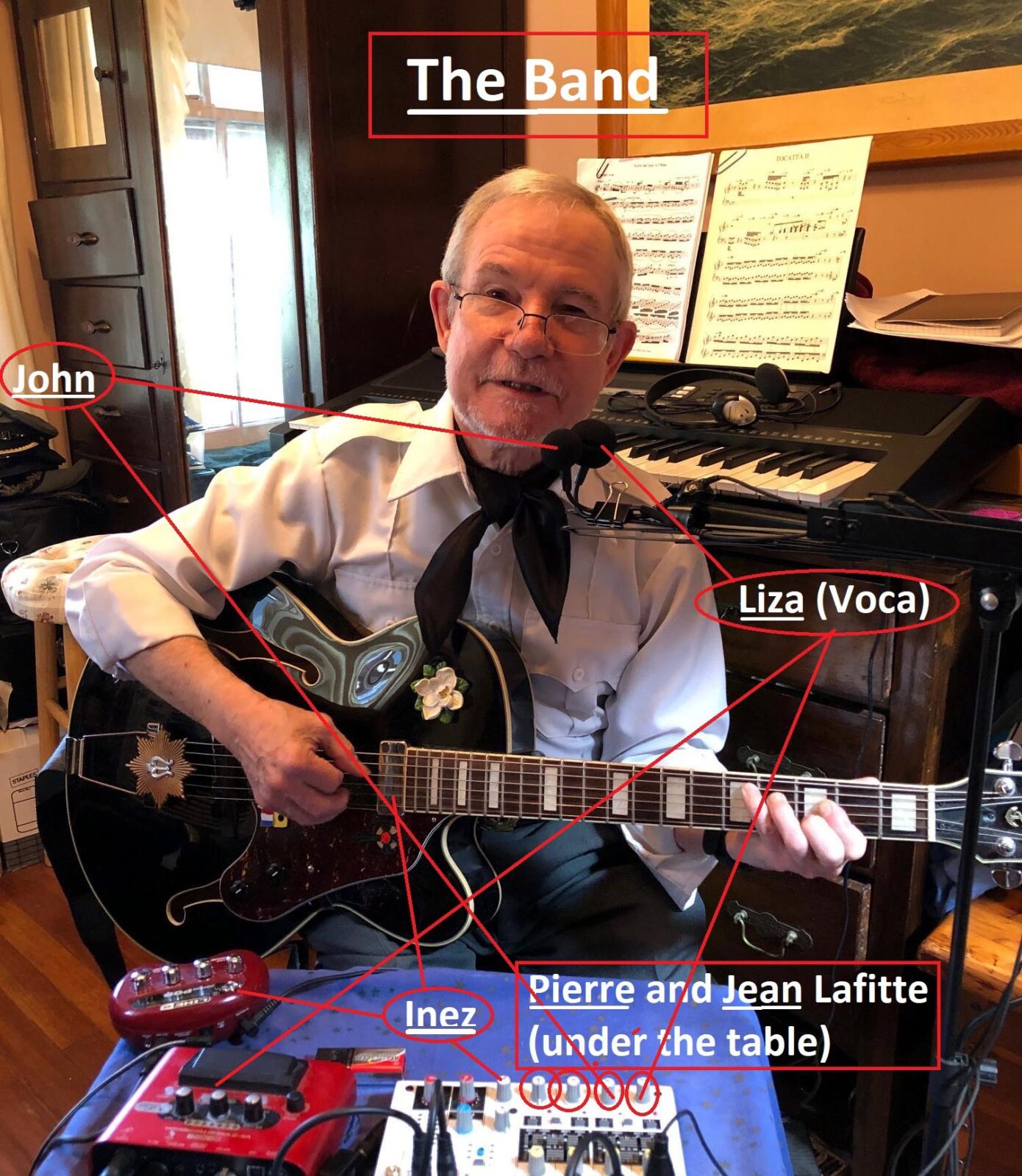

‘The Old Sailor’ (actually only two maritime songs there) was the result of the ending of another hiatus from public music after returning to the New York area. In 2015 a local DJ on Long Island who was building a home studio became interested in my music (mostly the East Coast blues stuff) and together he experimented with his new equipment and I with my music and newly-acquired metal clarinet and produced twenty-odd tracks, from which Lollipoppe chose the album, and subsequently John Kilgore remixed.

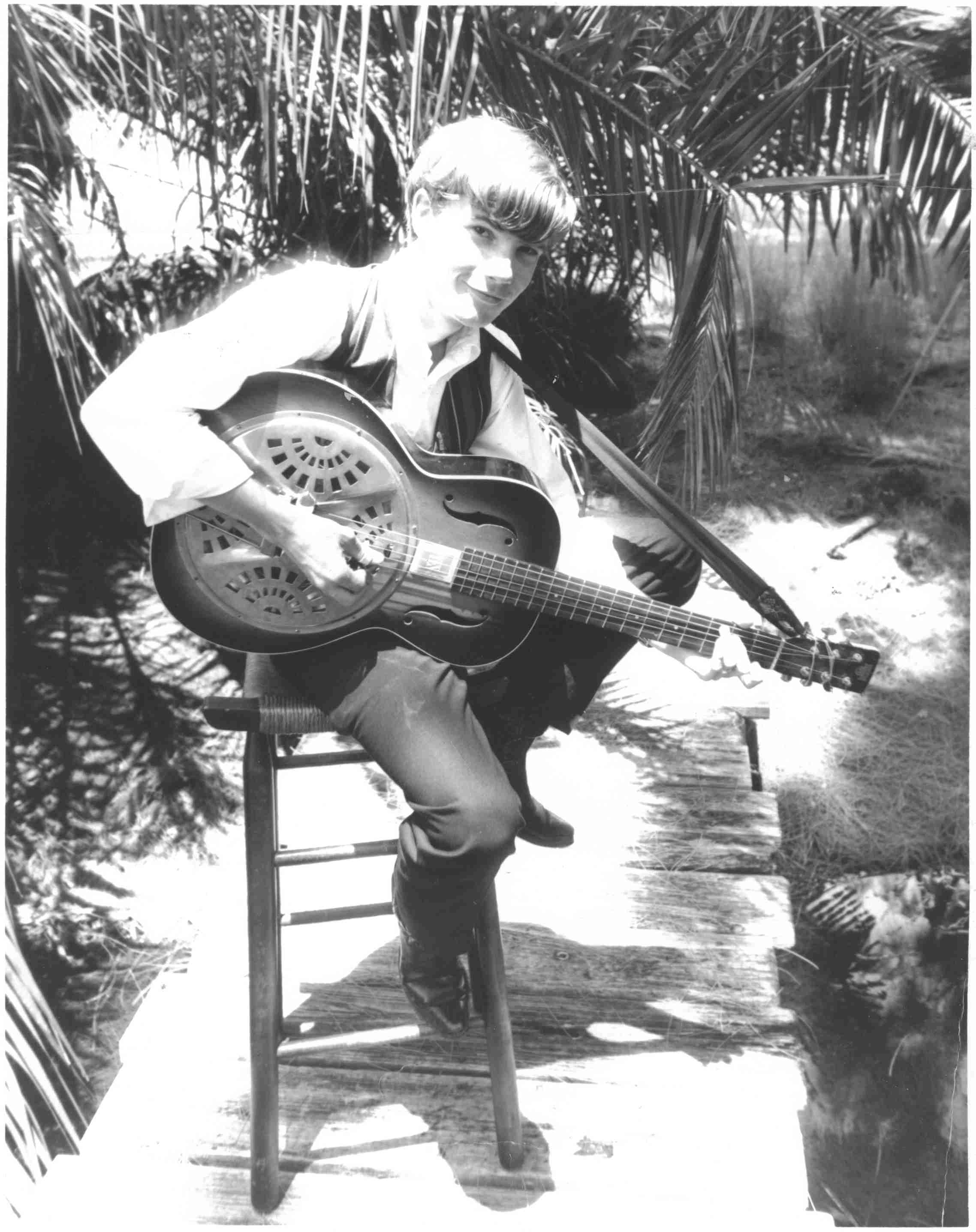

You studied guitar with Rev. Gary Davis in the early 1960’s and played in coffee houses in New York City, meeting almost everyone you could imagine in that scene. Do you agree that the latest album is a culmination of the past experiences?

Certainly it’s a major step along the way, combining the multiple musical aspects of a non-linear life. There’s more to come, as the technique of playing and singing with foot drums to give a solid live track was just born toward the end of the ‘Old Sailor’ sessions, and it’s what I do entirely now, but with electric foot drums and a harmonizer, a combination that frees up both guitar and vocals to expand into a full band sound. Rough live version here from last spring here.

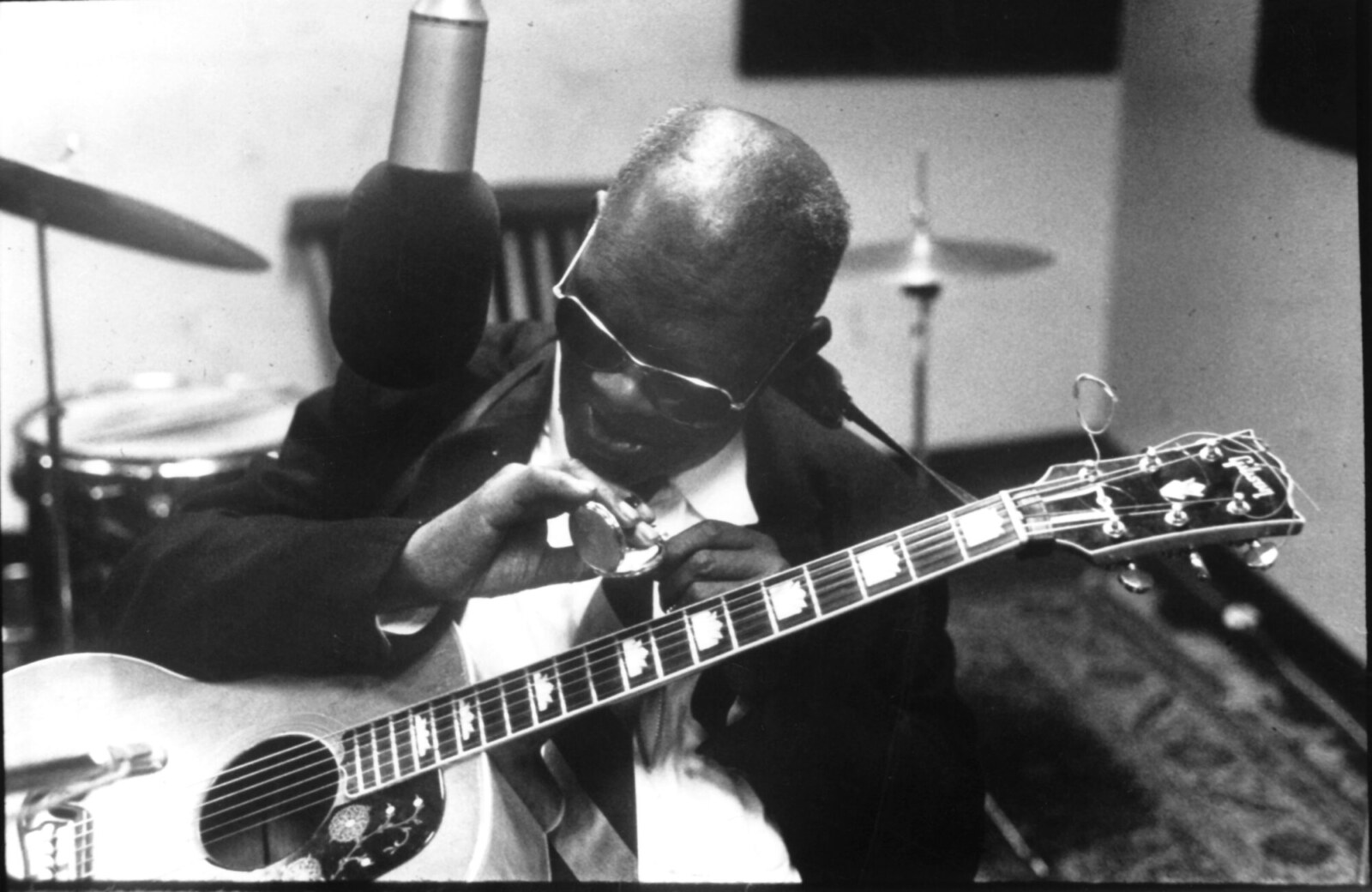

How was to study with Rev. Gary Davis?

Everything goes back to the Rev. Gary Davis, for whom I left college after only a semester to go to New York to learn from him. There has never been a guitarist who so successfully strove to make the guitar sound like a whole band behind a full-blast vocal, something that takes extraordinary virtuosity and originality to achieve. My most charged memories are of taking the subway to the Bronx, where he and his wife lived in a ramshackle building in the back yard of an old tenement.

Nothing was warmer, more inviting, and more musically amazing than sitting next to him and trying to learn how he did it all. Indeed, in my lowest, impoverished basket-house days, he even hired me to be his driver to various gigs around the NE and to run daily errands for his wife Sister Annie (like going from butcher to butcher to pick out all the elements of a head cheese she was making). He only took cat naps, so I got so little sleep I nearly wrecked his 1957 white Ford Fairlane (close call), but every moment felt like history in the making, utterly compelling.

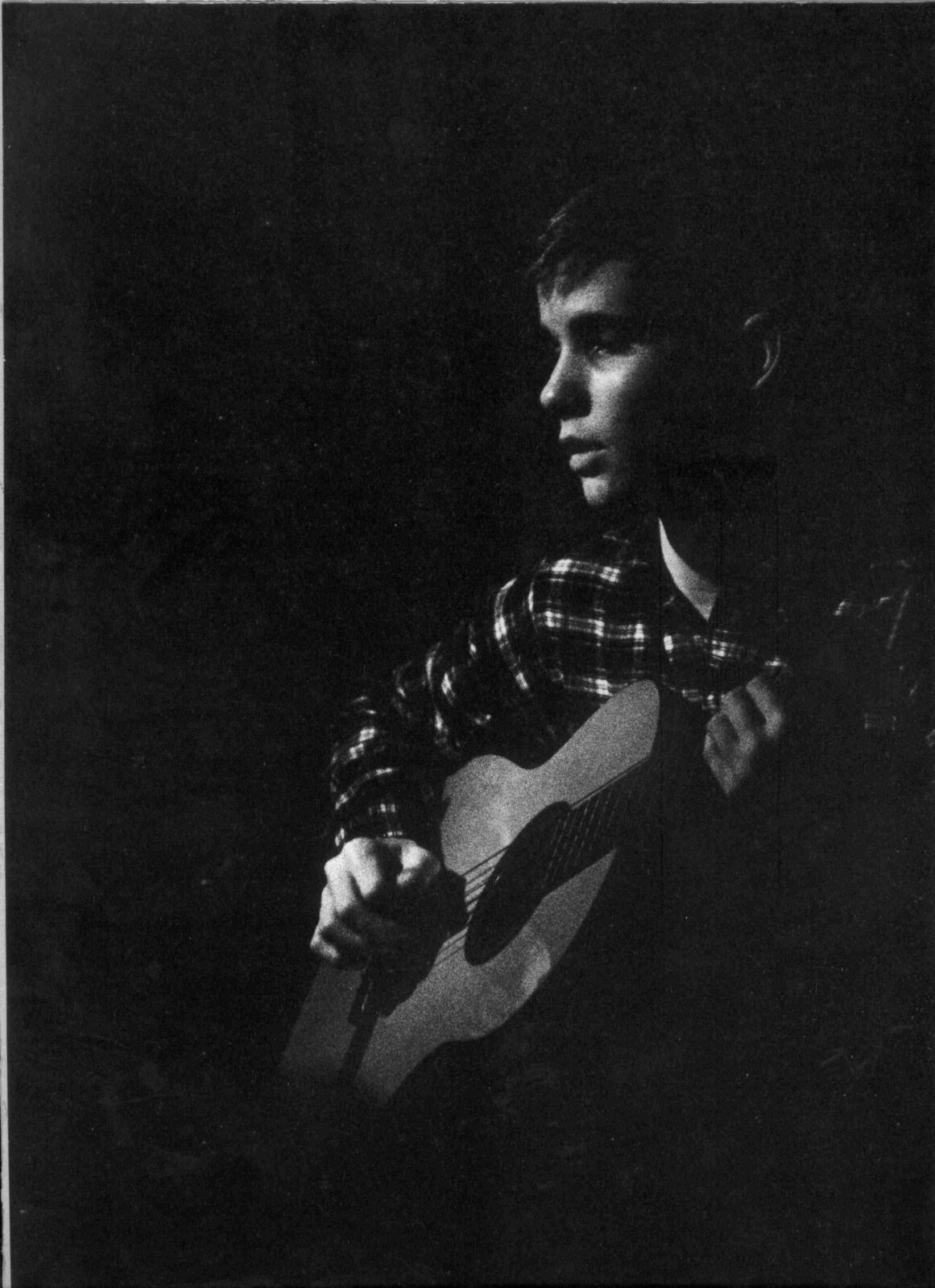

What are some names you met back then playing in New York? Do you remember a story that still warms your heart?

There are many, as there were so many warm-hearted people around back then, before pop music really got its grip on folk music. Playing guitar-banjo duets with Peter Torkelson (later Tork of The Monkees), the sweetest guy you’d ever meet. Or a reunion with him in his mid-Monkees house in Beverly Hills, when I walked out of the shower and there was David Crosby (Hi, Johnny!) whom I had known from my teen days in Coconut Grove where my family’s house was at the center of the folk music revival (Phil Ochs, at whose spare NY wedding I was best man and Gilly the one bridesmaid, did his demos on my dad’s Sony tape recorder). Had another fun encounter trading stuff with David when he came through Boston (where the Magicians were rehearsing) with the Byrds, but too many chemicals involved in that to go further…

And Jack Elliot, a big influence and major folk star at the time, later to turn up as rigger on the tall ship Elissa, for whom I was on a mission on my very first lesson with Rev. Davis. He had a particular piece by Davis he wanted me to learn and teach him. Well, I dutifully learned it, then when I got back to my Sullivan St. apartment shared with Peter La Farge, I totally forgot it! I was panicked, about to let down two of my idols! Fortunately, it came back to me the next morning, and Jack was performing it at The Gaslight later that week.

And three whole months of playing third act at The Playhouse Café on MacDougal and 4th St., second act the Holy Modal Rounders, first act Fred Neil and Vince Martin (just up from Coconut Grove). Just watching the other two was like heaven…and every night I’d get paid to do it.

Just playing with the Magicians brought the opportunity to meet (and be second act to) some of the biggest idols and influences, like the Everly Brothers, two of the calmest and friendliest of the greats I ever came across. And Mary Wells, who assured me she was all Taurus, long before I discovered astrology.

Probably the most humorously jovial incident was with Davis himself. When driving him about, one of my tasks was to prevent him from procuring a pistol, which he was always trying to do. A blind man with a gun, can you imagine? But he had a long and rough career as a street singer, so he was always armed in some fashion. When he finished his ‘Apostolic’ album, he took me to the back bathroom to get paid $500 cash for the sessions…I jokingly said, “Gary, in such secrecy, what’s to prevent me from robbing you?” “Oh, you wouldn’t do that”, he said as I felt a slight prick under my chin. It was his stiletto literally touching my throat. We both had a good laugh, but the point was made…

What was Phil Ochs like?

Phil, like so many folkies in the early ’60s, came to Coconut Grove for the extensive folk scene there, sort of Greenwich Village South (there were seven working folk coffee-houses there at one point — that childlike photo of me by Life photographer Flip Schulke was in the first one), and my parents were the welcoming old folks there, so they all came to our house to chat, record, everything but smoke dope (that was kept quiet until after I left home, so as not to offend them, and protect me). So, Phil wound up recording his song demos on my dad’s Sony reel-to-reel and used them to get a record deal in NY. Later in NY, he and Alice needed to get married quick (pregnancy) and Gilly and I (who had earlier married in LA City Hall in similar circumstances) were the two witnesses they scooped up for their marriage at NY City Hall. And of course, as folk broke up into pop, protest songs became no longer the rage, families broke up, everything changed. That was the death of Phil, sadly, though some of us remained in touch once into the pop scene (like Crosby, Tork), but by the ’70s everyone had dispersed, though many remained in folk or on the edges of it — Pat Sky, Buffy Sainte-Marie, Jack Elliot, Dave Van Ronk, Tom Rush, more) — some stayed in music, others diversified. I was never so surprised as to run into Jack and Pattie living in a small RV and being the rigger on the tall ship Elissa in Galveston, while still going on to earn multiple Grammys for his music. Another non-linear life of adventure, for sure.

Is there any unreleased material?

One already mixed that didn’t get used, and a handful of others, but they mostly have noticeable mistakes on them, expect I could do them better now.

What are some of the highlights from being a sound engineer?

Well, I wouldn’t call myself a proper engineer, more of a developer, but one of them is to learn not to spill Coke onto the board, it’s hell to take it apart and clean every switch…

Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

In maritime, not the usual shanties but the several Charles Dibdin songs on both ‘Top Hits’ and ‘Chesapeake’. He was probably England’s greatest pop songwriter, next to Paul McCartney, and he was totally forgotten. When researching for ‘Top Hits’, among the popular songsters of the day, his were the ones that always stood out, both musically and lyrically.

In my own songs, ‘Another Lifetime’ is the most personal, and another, ‘Home Is Where The Heart Is’, the title theme song for an underground NY film in which Jessica Lange played her first-ever role. The Apostolic Family recorded it live for the track, but it’s yet to be recorded properly.

As for gigs, there are many odd memories. Having to play under the table (to avoid beer bottles crossing over in the air), at a Coast Guard gig with the Apostolic Family. Or leading two million people in song (with the Press Gang) along both sides of the Mersey River as the 1984 tall ships paraded past. In Poland, where sea shanties and electric shanty bands have long been a pop phenomenon, being lifted on the multiple arms of a mosh pit and carried onto the stage. Who ever though folk music would come to that? But now, who knows, it’s suddenly The Year of the Shanty…

You’re also a professional astrologer and you published eight books on the subject.

It came into focus as everyone at Apostolic was searching for the mysterious, mystic, and generally ineffable, which was such a characteristic of the ‘60s. I ran across a leading astrologer, Al H. Morrison, who by chance needed a new office/apartment, and Apostolic had some extra space on its sixth floor rental loft, so we made a deal that he could have it in return for doing the charts of all our clients. I studied with him, and later another major astrologer, Charles Jayne, and just as Apostolic sank, I found myself afloat in another profession, my first book introducing a technique (the composite chart) that most astrologers use to this day. My main emphasis has been on establishing a physical basis for astrology (something almost no astrologer even cares about), and how that may also be bound together by seriality, which itself was proposed by biologist Paul Kammerer in 1919, about whom I’ve written a book, and am looking for backing for a film. Lots more on my website.

Are still in touch with any of the mentioned musicians?

Some, at a distance, as nobody lives around here, all dispersed. Jay and Lyn, for sure, and John Kilgore (he does live near, in Brooklyn Heights). A bunce of shanty folks on Facebook, but haven’t personally seen them in an age. That’s really about it. Long Island is a desert for me, not for lack of musicians, but for lack of interesting ones, especially generalists like myself who mix and match and blend. Everybody’s got a niche (Celtic, blues, “roots”, old-timey, bluegrass, lots more) but not adventurous between them as folks used to be. I had hoped the Internet would be the great diversifier, tearing down walls with new sounds, but it has mostly been the opposite, isolationist, at least in America. Not so much so in Europe, reasons for me to go there…

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

I guess I would just have to recommend pursuing a non-serial life, to go where the muse (be it Urania, Polyhymnia, or any of the others) beckons, joyfully and fearlessly. To quote Yogi Berra, when you come to a fork in the road, take it… John Townley

Klemen Breznikar

John Townley Official Website

Lollipoppe Shoppe Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp