Asmus Tietchens | Interview | “Absolute Music”

Asmus Tietchens is a German composer of avant-garde music who has pursued “absolute music” through an almost mathematical process of rigid formal exercises.

Tietchens also records under the monikers Hematic Sunsets and Club of Rome. He became interested in experimental music and musique concrète as a child, and began recording sound experiments in 1965 with electronic musical instruments, synthesizers and tape loops. In the 1970s he met producer Okko Bekker, and the two formed a decades-long partnership. Peter Baumann of Tangerine Dream heard a recording of Tietchens’ music and offered to produce an album; the result was ‘Nachtstücke (Expressions Et Perspectives Sonores Intemporelles)’. In 1984 he recorded ‘Formen Letzer Hausmusik’ for Nurse With Wound’s label United Dairies. On this release he began moving toward more abstract sound collages. He has taught acoustics in Hamburg since 1990. Tietchens specializes in irregular patterns of sonic abstractions that are suspended in gray drones to create cold textural voids from external references. His music is often inspired by and refers to the texts of the philosopher Emil Cioran.

“Why should I intrude my thoughts on any other human being?”

Where and when did you grow up? Was music a big part of your family life?

Asmus Tietchens: I grew up in Hamburg. None of my relatives were interested in making music. In a way, I educated myself about music by listening to the respective night programs on the radio. Around 1955 – 1958 I got my first information about electronic music and musique concréte. Strange to say but the young boy (8 – 10 years old) was deeply fascinated. My parents were shocked.

“I was interested in cutting tapes of all sorts into tiny snippets and afterwards putting the snippets together randomly”

What were your first musical involvements?

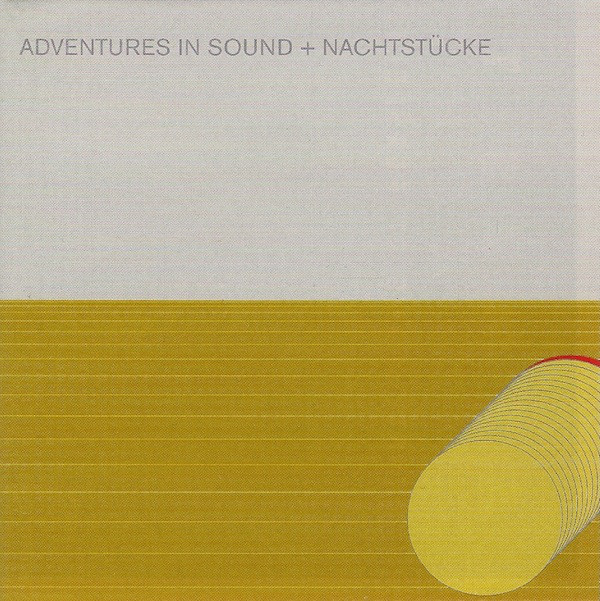

That was 1964, when I decided not to learn an instrument e.g. guitar or keyboard. Much more I was interested in cutting tapes of all sorts into tiny snippets and afterwards putting the snippets together randomly. Of course that all happened in an absolutely amateurish way. Far and wide no professional equipment. But I deeply enjoyed to de-construct the Beatles and the Stones with this method. My first “serious” piece of tape music (‚’A Quarter to Ten’) has been recorded in 1965. You can hear it on the CD ‘Adventures In Sound + Nachtstücke’ released 2003 by the German label Die Stadt. It is without any electronics, just a tape collage.

“Absolute Music means that it contains no message except an esthetic one”

Your work is associated with “Absolute Music”. Would you like to talk a bit about your background and influences?

“Absolute Music” means that it contains no message except an esthetic one. “Absolute Music” is not connected with any political, spiritual, ideological or educational intention. The listener is totally free for his own impressions, feelings, possible pictures and thoughts when listening to “Absolute Music”. To me that is total freedom of perception. I am no teacher, no philosopher, no scientist – why should I intrude my thoughts on any other human being? I always try to let the music speak for itself. That should be enough.

What’s most appealing about Karlheinz Stockhausen’s early electronic work to you?

Before Stockhausen recorded his ‘Studie 1 + 2’ and ‘Gesang der Jünglinge’ composers like Herbert Eimert and Karel Goeyvaerts already have created electronic music based on the theories of Werner Meyer-Eppler who underlined basics of cybernetics and information theory. Anyway, the most fascinating of that very early non-instrumental electronic music – no Theremin, no Ondes Martenot, no Trautonium – was on the one hand the use of sine waves (which do not occur in nature) and the tape cutting technique, and on the other hand – almost more important – the atonal approach. Strange enough ‘Gesang der Jünglinge (im Feuerofen)’ is based on words taken from the Book Daniel of the Old Testament. In the early 1950s the your composers in Cologne were still under the spell of World War 2 and thus tried to create a music far beyond all traditional methods, a music without pathos and dangerous narratives. They tried to create an objective music.

“Each piece has its own rules”

Would you mind telling us about the concept of irregular patterns of sonic abstractions in your music?

There is no concept in my music. Much more each piece (or a series of similar pieces) has its own rules which depend on the respective sound material. Facing this you can imagine that I quite often change the rules regarding durations, volumes and treatments.

“Cioran’s skepticism really helped and still helps me to understand what happens on our planet”

Where did Emil Cioran come into the picture? How did you first get interested in his work?

In 1968 when I get by chance Cioran’s ‘Lehre vom Zerfall’ (released 1953). Among others this book mercilessly get rid of all political, philosophical and spiritual systems and theories without creating another philosophy. In 1968 ‘Lehre vom Zerfall’ was Cioran’s one and only book which was translated in German language, except ‘Geschichte und Utopie’ (1965). All his other essays should follow not before the 70s. Cioran’s skepticism really helped and still helps me to understand what happens on our planet.

You were making first experiments already in 1965 with electronic musical instruments, synthesizers and tape loops.

My very first steps into experimental music were without electronics. From 1965 – 1971 I used e.g. electric guitar, piano, self recorded noises from different sources. But my most important “instrument” was the semi-professional tape machine Revox A77. Cut ups, loops, multi layered recordings (not multi track!) and speed variations were possible. So I would describe my music in that period as tape music, not really electronic music. In 1971 I got for the first time access to a Minimoog, a 4-track tape machine and a more advanced studio periphery. From that on I decided to make electronic music. The studio grew up quite quickly: 8-track tape machine and end of the 70s a 16-track machine with a proper mixing desk and a lot of up to date devices.

How did you meet producer Okko Bekker? Would you describe your relationship with him?

Okko and me were school mates and already met in 1963. We had a lot of common musical interests and soon started collaborations with our tape recorders and instruments. Opposite to me Okko soon became a professional musician and composer. He earned a lot of money and continuously built up the Audiplex Studios. Being buddies he always allowed me (and still allows) to work in his studio. Since 1979 he is my producer. Though our musical approaches meanwhile differ totally we are still best friends.

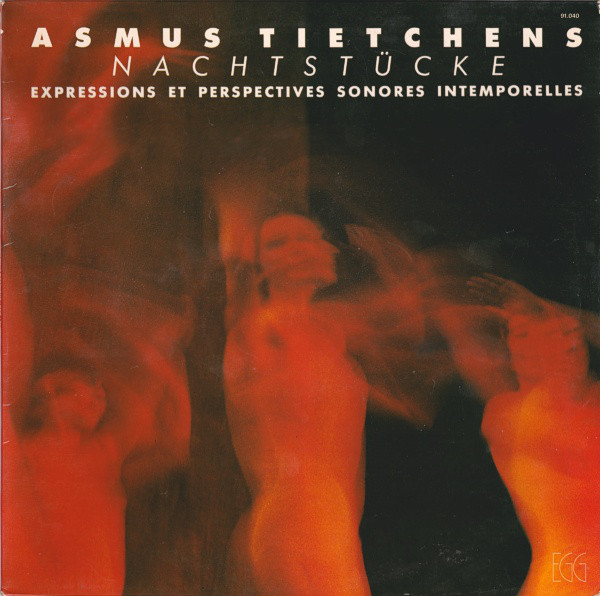

How did Peter Baumann (Tangerine Dream) hear your recordings which eventually led to your debut album, ‘Nachtstücke’?

When Cluster 1978 recorded ‘Großes Wasser’ in Baumann’s Paragon Studio it happened between two recording sessions that Roedelius played a cassette with my music to Moebius. By chance Baumann came along and asked who is that musician. To make the story short: Two days later I came to Berlin to sign the contract for ‘Nachtstücke’ which hasn’t been released until 1980. The album contains pieces I’ve recorded in 1976 – 1978. I used the Moog Sonic Six and an Otari 8-track machine for that series. ‘Nachtstücke’ was the peak of quite romantic and mostly too long synth pieces without drum machine. The album was extremely unsuccessful because it was no “Kraut”, but even if it were Kraut – the Kraut movement was over in 1978. And the album was absolutely not New Wave, Neue Deutsche Welle or Industrial. So when the album got released it already was an anachronism. R.I.P.

You appeared on ‘One’ by Cluster & Eno. How did that come along?

Sky Records let all their LPs cut in Hamburg. And for this reason once Cluster came with the tapes of ‘Cluster + Eno’ to Hamburg but they had recorded only 32 minutes and the next day they had an appointment at the cutting studio. 32 minutes are not enough for a proper album. So we recorded ‘One’ all night long with Okko and me as guest musicians. Of course without Eno.

You were also part of a one-off supergroup project featuring Dieter Moebius from Cluster, engineer Conny Plank, Kraan musicians: Johannes Pappert and Helmut Hattler, and Okko Bekker. What’s the story behind making ‘Liliental’?

1976 Möbius invited me to a collaboration album to be recorded at Conny Plank’s studio. He gave us seven days of his studio capacity. In the moment we arrived at Conny’s studio Kraan – who had just finished the recordings for their next album – departed. But before they really departed we had some coffees and cigarettes. And due to a spontaneous decision Hattler and Pappert were invited to our collaboration. Both musicians joined us for all seven days. ‘Liliental’ was a project with open end. We did not have any concept or compositions – nothing. The pieces were improvised to be followed by post-production treatments months later.

Several very interesting releases followed, ‘Biotop’, ‘In die Nacht’, ‘Musik an der Grenze’, ‘Musik im Schatten’, ‘Spät – Europa’, ‘Litia’, ‘Musik Unter Tage’.

Soon after the “romantic” pieces which you can hear on ‘Nachtstücke’ I began in 1979 to experiment with Moog Sonic Six and the drum machine Roland CR78. The duration of the pieces should not exceed three minutes. The pseudo-pop direction of my four Sky albums interested me approximal three years. Finally (‘Litia’) I even purchased the MFB 512 which was one of the first digital rhythm machines. Anyway, already 1982 my interest in this kind of pseudo-pop decreased totally. But I had to fulfill a contract with Sky Records for two more albums. So having no alternative I recorded ‘In die Nacht’ and ‘Litia’. But all along I was much more interested in “Industrial Music”. Of course Sky Records was not ready to release such noisy stuff. Dammned hippies, haha. So I let the cassette labels Yorkhouse Records (UK) and Aeon (USA) release my more abstract music parallel to the Sky releases. These four cassettes stylistically picked up the thread of what I began in the late 60s and very early 70s.

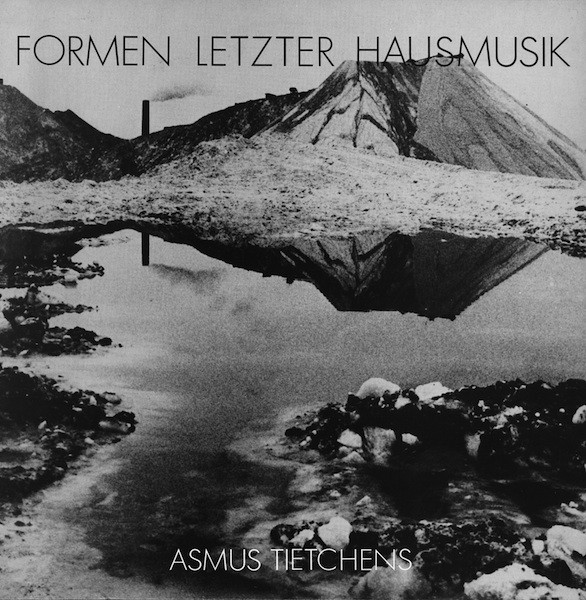

Your approach changed quite a bit on ‘Formen letzter Hausmusik’. What’s the story about this unique album?

To me this album is one of the most important releases because it is the missing link between my musical past of the early 70s and my musical future, only interrupted for three years by the Sky period. More than half of the pieces on ‘Formen letzter Hausmusik’ has been recorded between 1970 – 1974. And it is important because it clearly shows the beginning of my further musical and esthetic development. Here once again thanks to Steven Stapleton for having released ‘Formen letzter Hausmusik’ on United Dairies.

You began moving toward more abstract sound collages.

As I already said above: I lost interest in all that electronic stuff connoted with Kraut, although Kraftwerk, Can, Neu! and Cluster remain as heroes. But my own musical targets tend into a more abstract direction, hopefully far away from fashionable trends.

What about the Club of Rome or Hematic Sunsets? How would you classify these in your discography?

The moniker “Club of Rome” was no more than a test to see whether the respective music also sells without my name. I never used it again although ADN immediately sold all copies of the cassette. The Hematic Sunsets (anagram of my name) is a project to satisfy my secret (?) passion for cheesy lounge music. In a way it stands in the tradition of the Sky albums but without their strange seriousness. ‘Aroma Club 1 – 4’ have all the same sound source: A cheap Yamaha home organ. Only the 5th one (‘Aroma Club Adieu’, released a month ago) is a mixture of Yamaha, old analog synths and other sources. This is definitely the final album of the Hematic Sunsets. Mission accomplished.

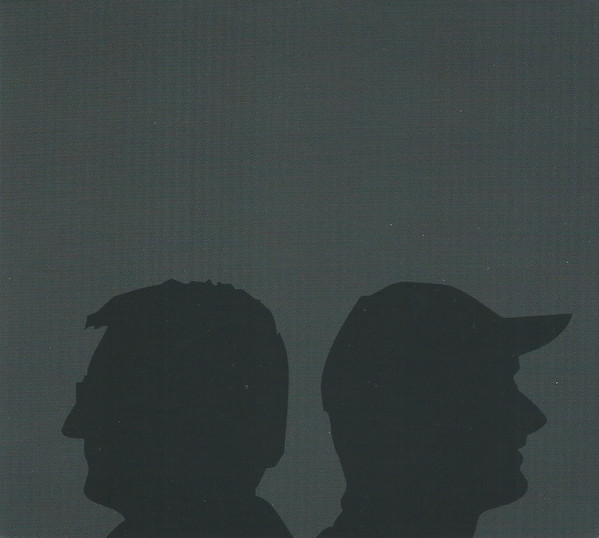

How was to collaborate with Moebius in 2012?

When we departed from Plank’s studio after the session for ‘Liliental’ Moebius suggested to record an album with just him and me. We both agreed. For thousands of reasons it took 35 years to redeem this appointment. In the meantime we’ve met very often and have discussed the collaboration again and again. Finally we decided not to meet in a studio but to exchange files created in our respective studios. Before we’ve finished the recordings Bureau B already showed interest to release the album. As far as I know it was Moebius’ last collaboration before he passed away in 2015.

Then there’s the Kontakt der Jünglinge project with Thomas Köner.

1988 the Dutch CEM Studio (Arnhem) invited me to conduct a weeklong workshop. Funny enough the very young Thomas Köner was the one and only student. Never heard about him before. He has not released any CD yet. Anyway, for me and obviously for him, too, it was a very inspiring week at the CEM studio. In the late 90s Thomas suggested live appearances. Meanwhile he has released important albums and so it was no problem to get gigs. Some of them are documented on the four KdJ releases. Only our fifth release ‘Makrophonie 1’ is a studio album. The concerts are always a mixture of Thomas’ deep isolationism and my more minimalistic approach. The name “Kontakt der Jünglinge” is a combination of Stockhausen’s famous pieces ‘Kontakte’ and ‘Gesang der Jünglinge’. Here and then people suspected we could be a gay group: Jüngling = young man, Kontakt = contact. Just as funny as wrong.

Last year you collaborated with Frans de Waard on ‘Oordeel‘.

Frans and I are good friends since the late 80s and we agree with a lot of esthetic and musical subjects. Frans has released two Tietchens LPs on the Korm Plastics ambient series and a cassette on Korm Plastics. But never collaborated. 2018 Frans performed in Hamburg and we asked: “Why the hell we have not recorded a joint album, yet?”. After that evening in Hamburg we started as quickly as possible to record ‘Oordeel’.

Your latest release is with Dirk Serries. What’s the story behind ‘Air’?

Dirk delivered extreme minimalistic basic material which he has created with wind instruments. Thus the title ‘Air’. This collaboration differed totally from the ones we did during his Vidna Obmana period. The latter one is an example for electronic maximalism, and ‘Air’ is the opposite – a study in minimalism.

It’s absolutely impossible to cover your discography. Would it be possible for you to choose a few collaborations that still warm your heart?

No. You see, all collaborations I do with all my soul. There are no preferences. Even in retrospective.

What currently occupies your life?

Not so much, Corona… but the recordings for a new album. Hamburg also is in lockdown and luckily I can barricade myself in the studio.

How are you coping with the current pandemic and what are your predictions for the future?

My magic mirror is dull.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

60s: Pink Floyd ‘A Saucerful of Secrets’, White Noise ‘Electric Storm in Hell’

70s: Cluster ‘Sowiesoso’, Residents ‘Duck Stab/Buster & Glen’

80s: Dome ‘1’, Organum ‘In Extremis’

90s: Oval ‘Systemisch’, Richard Chartier ‘Direct, Incidental, Consequential’

00s: Ryoji Ikeda ‘Time And Space’, Autopoieses ‘La Vie A Noir’

10s: The Telescopes ‘As Light Return’, Ström ‘untitled’

Recent: Francois Buffet ‘Le Songe Du Retour’, Alva Noto ‘Xerrox 4’

Caution!!! The above mentioned albums are no more than peaks of icebergs among a lot of other favourites.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

Thank you for having interviewed me.

Klemen Breznikar

Asmus Tietchens Official Website / Facebook / Twitter / Bandcamp

Headline photo: Asmus Tietchens in the studio in 1980 listening to the master of ‘Biotop’.