Sproton Layer | Mission of Burma | Interview

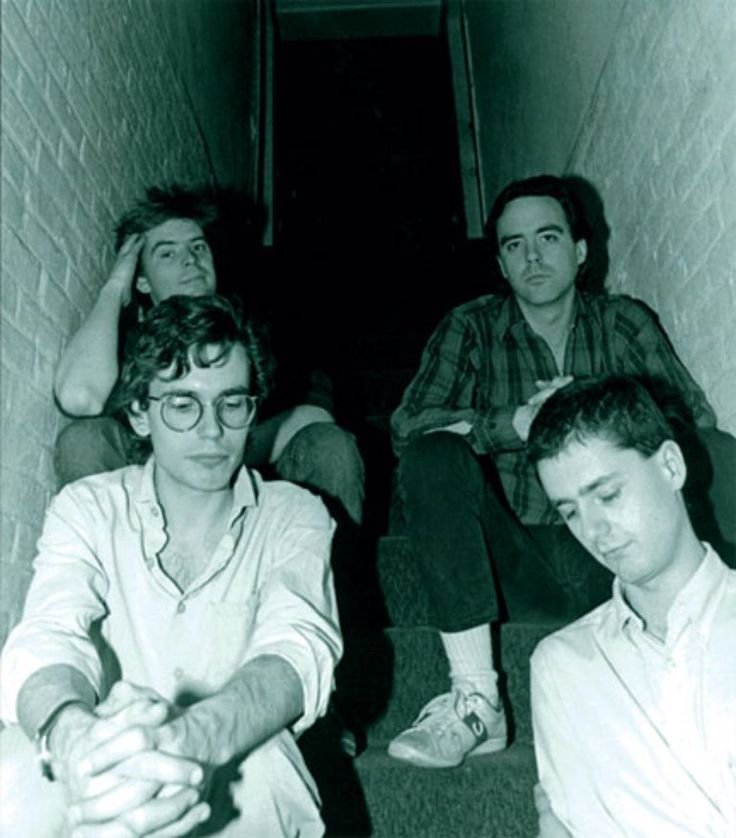

Sproton Layer was a psychedelic rock band that emerged from the vibrant musical landscape of Ann Arbor, Michigan, in the late 1960s.

Comprising the three Miller brothers—Roger, Ben, and Laurence—the group embraced the experimental spirit of the era, creating music that was both avant-garde and richly melodic. Their sound was a unique blend of fuzzed-out guitars, trippy effects, and complex arrangements, drawing inspiration from iconic bands like Pink Floyd and Soft Machine while forging a distinct identity of their own.

Formed when the Miller brothers were still in their teens, Sproton Layer quickly developed a reputation for their boundary-pushing approach to rock music. They were known for their unpredictable live performances, where they showcased their knack for intricate musical structures and genre-defying creativity. Despite their early dissolution in 1970, the band’s impact lived on, with members going on to pursue successful careers in music, most notably Roger Miller’s work with the influential post-punk band Mission of Burma.

In 2011, Sproton Layer’s legacy was celebrated with the reissue of their album ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted,’ offering a new generation a glimpse into the experimental ethos and psychedelic energy that made the band a cult favorite.

“We’d get stoned seeing the MC5 at a free concert in the afternoon”

Where and when did you grow up? Who were your major influences?

Where and when did you grow up? Who were your major influences?

Roger Miller: We grew up in Ann Arbor, Michigan. It’s a big college town, so it had a rich cultural scene. Our father played classical piano when he was younger, and he would play Mozart, Saint-Saëns, and Stravinsky records in the evening when we were going to sleep. Sometimes we’d go to classical concerts, which was a significant influence. I took piano lessons as a kid, played French horn in junior high, and soon after The Beatles hit (6th grade for me), I picked up the guitar.

Our father studied fish that live in the desert, both live ones in isolated springs and fossils, comparing the species/evolution. So we spent our summer vacations on field trips in the desert. That, combined with the great Arboretum in Ann Arbor and a local forest called Grave’s Woods, gave us a deep appreciation for nature that shaped our outlook.

When psychedelic rock emerged, and Dad heard the sounds we were making, he introduced us to the modern music series at the University of Michigan’s music school called ‘Contemporary Directions,’ which we eagerly attended. We’d get stoned while watching the MC5 at a free concert in the afternoon, then toke up again and go hear Stockhausen or Terry Riley in the evening. Not a bad deal, all things considered.

Ann Arbor’s reputation as the home of revolution, with the MC5, John Sinclair and the White Panthers, and The Stooges, made it an exhilarating place to grow up. I saw Jimi Hendrix in a tiny club where there were only about 100 people. There was a lot of energy in Ann Arbor in those days, ideal for generating new ideas.

Ben Miller: My earliest influences began with my father’s love of Classical, Romantic, and 20th-century music—Mozart, Brahms, Stravinsky. The British Invasion hit me when I was a pre-teen, and that was when I heard my “calling.” Those bands, along with The Standells and The Seeds, blurred into the psychedelic movement with bands like the 13th Floor Elevators, Jimi Hendrix, Soft Machine, Silver Apples, and Cream—too many rock bands and influences to count, really. Blues music didn’t interest me much, even though it was considered avant-garde for white folks to play back then. Nor was jazz a significant influence. My brothers and I knew nothing of free jazz or free improvisation until well after our own explorations of free-form improvisation—what we called “Space Jams.” As three brothers who were adamantly exploring New Music, we would often go to a local concert series called ‘Contemporary Directions,’ where electronic tape music and performances by notable avant-garde composers were featured, such as Stockhausen and John Cage.

Perhaps Sproton Layer’s biggest influence was Pink Floyd’s ‘The Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ and ‘A Saucerful of Secrets.’ Alice Cooper’s ‘Pretties for You,’ Ann Arbor’s SRC (first album only), early Captain Beefheart, and early Tyrannosaurus Rex were also heavy on our playlist. It was the fragmented song structure and improvisation component (“Interstellar Overdrive,” in particular) that spurred me into trying to write songs that portrayed a different world instead of the standard “boy-meets-girl” lyrics—the commercial Top 40 music of those times. Nature was also a big part of our creative inspiration. Since our parents were scientists, and we had much exposure to “the great outdoors,” the spirit of nature often found its way into our songwriting.

Laurence Miller: We grew up in a progressive college town, in a supportive family that encouraged following one’s dreams. Our dad was an esteemed Paleo-ichthyologist professor at the university, but he had originally wanted to become a concert pianist. He even won a large silver trophy as a teenager, which I remember was proudly displayed on the living room mantel for most of our childhood. Dad would take us to classical concerts and modern 20th-century performances regularly, with composers ranging from Stravinsky and Beethoven to Stockhausen and John Cage. Our sister, who also played piano well, would take us to “electronic music concerts,” where analogue magnetic tape was the medium for sound. As musical brothers, we were all very impressed and influenced by these experiences. I took piano and clarinet lessons in my youth, later teaching myself how to play the guitar and drums. Playing guitar wasn’t easy for me because I had to learn to play left-handed (upside down) on a right-handed guitar.

It was The Beatles and the British Invasion that gave us our first push, followed closely by psychedelic music from both the American and British scenes. Family summer trips out west, camping under the stars in the desert, also had a profound impact on our psyche. We were taught at an early age to respect “nature” and all living things. As for the local rock scene, my favorite bands were The MC5 and SRC. We would see them perform live at the free Sunday concerts all the time.

Before Sproton Layer, you were called Freak Trio? Was this your first band?

Roger: We were in a band called “The Sky High Purple Band” (forgive the name—we were only 15 and 13 at the time!), where we learned songs by The Kinks, 13th Floor Elevators, Love, the first Doors album, and The Mothers of Invention, among others. This was in 1967, and it was a really good educational experience. We played in a friend’s attic and a friend’s garage. When I went into high school, the band folded—what high school kid wants to be in a band with junior high school kids (my brothers were two years younger)? I then joined a blues band called “Mandrake Fields” and was in a power trio called “Factory” just before Freak Trio/Sproton Layer.

Ben: The first band I put together as a bandleader had seven guitarists. This was in 1968, when I was 14 years old. My composing ability was extremely limited, if not nonexistent, so the music was mostly in my mind. It was basically a sequence of simple rock riffs. What I could write down on paper and suggest for my friends to play didn’t translate well. After a couple of practices, we quit out of frustration.

Laurence: We had a cover band called “The Sky High Purple Band,” playing some of our favorite pop music from that time. It was a pretty darn good band, considering our age. I played tambourine and sang harmonies. I wrote an awful blues number called ‘Look Out Pretty Mama.’ That was a bit of an embarrassment, actually.

When and why did you change your name to Sproton Layer?

Roger: We did a lot of drawings while stoned and listening to music. I did a drawing while listening to the first ‘Soft Machine’ album in Spring 1969, and I looked at it later and saw the phrase “Sproton Layer” written on it. It seemed like a good name, evocative and unusual. When we added Harold Kirchen (his brother, Bill Kirchen, played guitar in Ann Arbor’s Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen), we couldn’t keep calling ourselves Freak Trio, so “Sproton Layer” was the next logical choice. That was in late fall 1969.

Here, I’d like to point out the meaning of the phrase ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted.’ In my enthusiasm for weed as the catalyst for creative powers (a charming thought at the time, but in retrospect not entirely accurate), I came up with that phrase. When a person hasn’t smoked weed, their magnetic fields are “normal,” and songs tend to follow standard chord progressions. But when someone has smoked weed, their magnetic fields get disrupted, and the chords come out in all sorts of unusual ways. This was essentially our manifesto for approaching the world of music!

Laurence: I don’t recall exactly why we changed our name to Sproton Layer. All I remember is the later meaning of the phrase, which referred (even if unofficially) to the mixture in a pipe—if more than one type of marijuana was used. That would create a “sproton layer.”

How do you remember some of the early sessions you had with your brothers?

Roger: The most important was Freak Trio Electric, March 1969, which marked the birth of the band. Our parents went out square-dancing, and for some reason, we had a tape recorder. We toked up and recorded our jams as a rock trio in the basement. We were stunned at the results! The biggest reference point was ‘Interstellar Overdrive,’ but our lack of blues-based riffs took these jams in pretty unconventional directions. The next day, we decided to form a band because this music was much more interesting than anything else any of us were doing.

Another memorable session was a week or so later when, once again, our parents went out for the night. This time, we brought all our instruments into the living room, where there was a piano. We also included a clarinet, sax, cornet, bongos, and other unconventional instruments. It was more “art-song” and referenced the Contemporary Directions concerts a bit more, less overtly “rock.” We called the session ‘At the Playgrounds of Olympus.’ We were again stunned at what we’d created out of nothing, just by playing together. It was a really dynamic time.

Ben: As brothers, we often got together and recorded not just as a rock band (Freak Trio, Sproton Layer), but also as three brothers high on weed playing outside in the woods, in one of our igloos we built in the backyard, or in the living room where our spinet piano was located. We used varied instrumentation that included not just electric guitars and parts of a drum kit, but also an alto saxophone, a cornet, a Bb clarinet, and anything else lying around that suited our fancy. I recall a jam that Roger and I did in the kitchen using just silverware and slamming cupboard doors. We felt this was not only fun, but that it was music too. It was from this profoundly creative setting that I felt free to do whatever came to mind, rather than working with confined instrumentation or within one particular genre with specific boundaries. I think because of this, I felt alien to those around me who saw music in such concise forms as blues-based rock, strict classical, or otherwise. That is partly why, as brothers, we worked together so well.

Laurence: It was incredibly euphoric. Freak Trio Electric perhaps established the beginning formation of my sense of our original music: “Forever Hopeful.” We had a crappy cassette player that we placed on the dryer at the other end of the room for that jam session. The playback afterward revealed a terribly lo-fi recording, but it successfully melded the music into one fantastic, churning bloom. There was a high-pitched ringing sound between each improvisation, which we identified at that time as “the Sound of the Ozone.” It was a concept that stuck. From there, we got together many times with a variety of traditional and unorthodox instrumentation. ‘At the Playgrounds of Olympus’ was one of my favorites. We firmly believed we were onto something very special.

Your album was recorded in 1970.

Roger: In my 12th-grade class at Pioneer High School, my friend Mark Brahce developed an interest in the band. He decided that he would record us. He had never done any recording before; he just started doing simple research. We did an initial session with him in December 1969 to get things going. By the time we recorded ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted’ (August/September 1970), he had learned a lot more. But this was an incredibly simple setup. We recorded it in our parents’ basement, hanging blankets on the clothesline for sound dampening. We only had six microphones, which we used to record the guitar, bass, trumpet, and drums. There were no EQ options at all—whatever the sounds were in the room, combined with microphone placement, was the final result. Once the instrumental tracks were recorded, we overdubbed vocals and minimal instrument overdubs in the same track. Every track was done in one take, with most vocal tracks done one right after the other. Once the vocals were laid onto the instrumental tracks via the Sound-on-Sound method, that was the mix. There was no remixing. It’s pretty amazing that it sounds as good as it does, and it’s a testament to Mark’s belief in the project and (dare I say it) the band’s focus to get these 12 songs that tight and inspired. I was 18 when this was recorded; Lar and Ben were 16, and Harold was 17.

Mark did a bit of recording with me in 1970/71, but nothing like this album. After that, he didn’t do any more recording!

As mentioned elsewhere, there was no label in mind—this was to be our calling card. But we got no interest from any bookers or labels. We had no ability to release it ourselves, of course. We were just kids!

Laurence: It was literally a basement recording. We recorded in our basement—the same room where we began, with our first spontaneous improv session: “Freak Trio Electric.”

Would you like to share some of the strongest memories from producing and recording your album?

Roger: It was all about focus, really. When we got good takes, we knew it. We were definitely on, as often happens when a band records. The collective improvisation in the second half of ‘Pretty Pictures, Now’ is just about as good as it could possibly have been.

We played croquet in the backyard for relaxation between recording sessions—that’s my biggest recollection!

Laurence: I honestly don’t have any distinct recollections.

What kind of equipment did you use?

Roger: I had a Montgomery Ward’s (Airline) bass—really bad bass, actually, but it had a unique sound. It didn’t look “typical” either. By the time we recorded ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted,’ I had an Ovation bass amp—Ovation didn’t last long in the amp business, but it had an odd ‘sinister’ look because the amp head was in the back of the amp, so all you saw was a large black, neo-leather-encased cabinet. Again, it wasn’t a great amp, but combined with the Airline bass, it produced a fairly unique tone and had an unusual look.

Ben: On ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted,’ I used a Gibson Epiphone solid-body with one pickup through an Acoustic 150 guitar amp. Acoustic was a solid-state amp, and at that time, transistor amps were viewed as a benefit over tube amps because they were cleaner. I did like the transistor crunch when the volume was jacked up, but the built-in distortion was awful, and the reverb was weak. When we were Freak Trio, I used a Kay and sometimes a Silvertone, running them through a Fender Bassman amp; a very different sound.

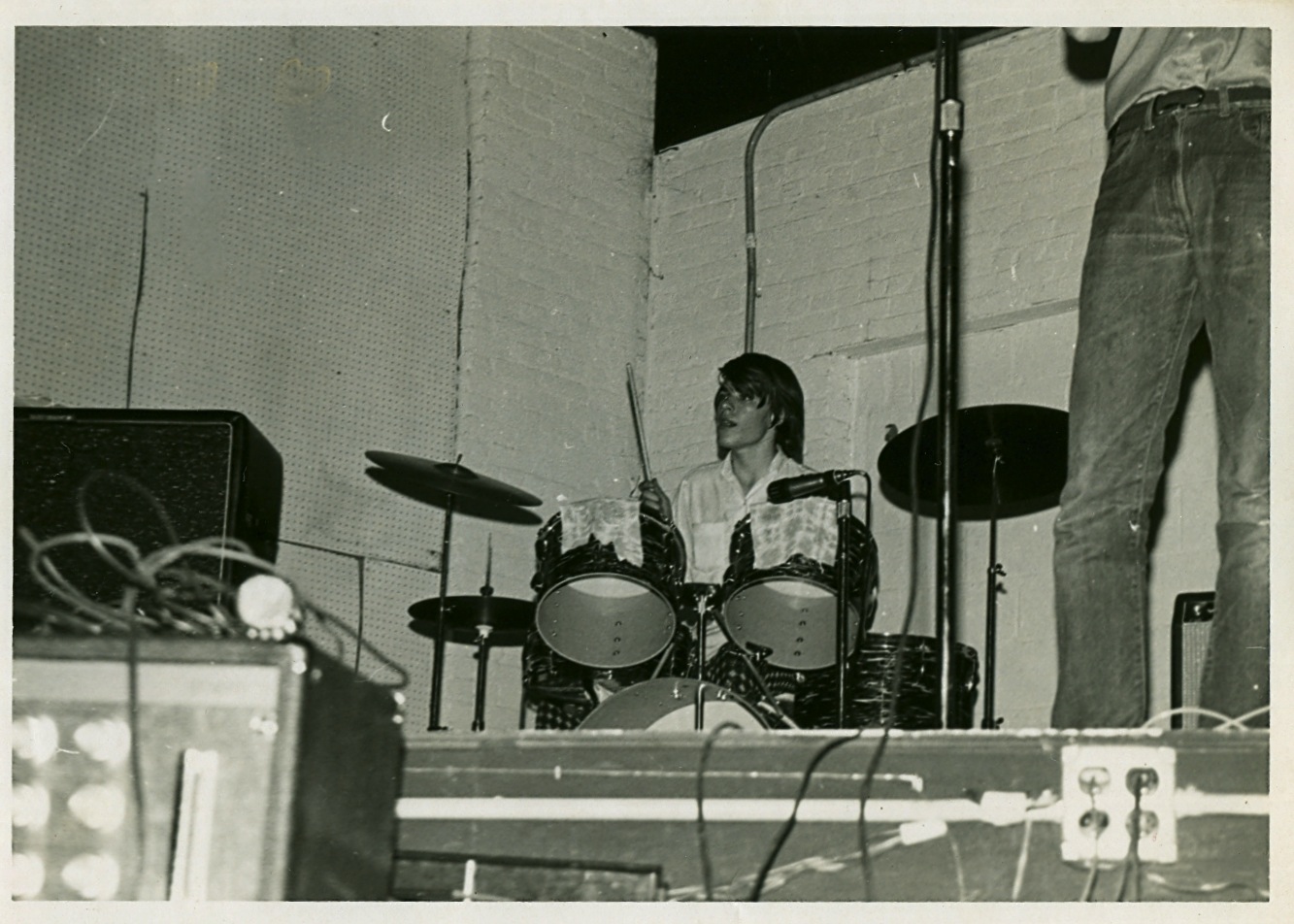

Laurence: I played a brown-swirl Yamaha drum set with double-rack toms. It was the only set we could afford. Sadly, in those days, “made in Japan” wasn’t considered a good thing, and such was the case. I draped rags over the tom-toms, taped to the edge of the heads, to create what I thought was a nice dead sound. But, when I first started in the band, I used another guy’s drum set that was set up in a right-handed formation. I, of course, didn’t know this, so I learned to play the drums as I did the guitar: on a right-handed set. This positioned my ride cymbal where the crash cymbal should have been and vice versa, with my crash cymbal where the ride cymbal should have been. Crash cymbals tend to be thin and smaller, while ride cymbals tend to be heavier and larger. Consequently, whenever I hit my crash, it truly CRASHED. It was very loud and brash. I intuitively thought of it as similar to the two cymbals commonly used in an orchestra for important accents in the music. Very dramatic. My ride cymbal, on the other hand, being smaller and thinner, didn’t take much energy to get going, and I liked the sound it produced. It reminded me of Ringo Starr’s sound—a kind of quaking “wash” effect. My foot pedal for the bass drum was a Speed King. That thing was breaking down all the time—I guess since I stomped on it so hard. My main objective as a drummer was not to play the square 4/4 backbeat, which most drummers used. Instead, I tried to create a visual effect with much of my playing, as much as propelling the music and lyrics forward. Perhaps my drumming influences could be summed up as orchestral in nature with a mix of Ginger Baker and Nick Mason.

Why wasn’t the album released in its time?

Roger: We had no label in mind—we just recorded it because Mark really liked us and wanted to do it, and we had the material. We considered it a calling card and sent it to the Rainbow Party (formerly the White Panthers) in Ann Arbor. No response—we weren’t a party/boogie band, which was what was popular by then. We also sent it to SRC’s manager—no positive reaction, which definitely hurt, as we were SRC fans. We got zero response. The times were becoming conservative, the expansive days of ’60s music were over, and we didn’t fit anywhere. Basically, after composing a pretty solid work, I was plunged into depression—I mean, how could no one care about this (remember, I was only 18)? It took until 1979 for me, 10 years after Sproton Layer began, to finally hit my stride when Mission of Burma started. In between, I did all sorts of stuff without a solid direction. But I did learn a lot about music while I stumbled around!

Your sound is pretty unique. It’s a kind of mixture of different styles.

Roger: We definitely thought of ourselves as psychedelic. Weed and acid played a big role in a lot of the songs. In some ways, we were kind of pre-prog—the term ‘prog’ had not yet come into common terminology, and our use of classical elements was organic, stemming from our own background. We definitely liked ‘Salty Dog’ by Procol Harum, and even the Ann Arbor band SRC had classical influences. ‘The Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ and the first Soft Machine album also used expanded song structures. We definitely were not a prog band, though. Much too organic and zonked out! Our youthful enthusiasm kept us from going over the top with exaggerated profundity, a hallmark of prog rock. We never played riffs to prove we were great—we only ever played them because they were what made sense to us.

Did the band tour to support the LP?

Roger: No touring, just 20 or so local shows from April 1969 to August 1970. We played a show on the University of Michigan campus with Carnal Kitchen, a free-jazz/rock band featuring Steve MacKay, who played with the Stooges. We went over pretty well there (at the ages of 17 and 15!). We played at a peace march near Detroit, but our more cerebral and complex music didn’t give the audience the “party-release” they really wanted, so it wasn’t as successful. The only club shows we played were at the Big Steel Ballroom in Ann Arbor, where the MC5 and SRC also played. Heh, I even saw the John Drake Shakedown there—he had been the lead singer for the Amboy Dukes before Ted Nugent fired him. I did some of the posters for the Big Steel Ballroom so I could get in for free, much like I did a few years earlier at the 5th Dimension (both in Ann Arbor).

In 1991, New Alliance released your album. Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

Roger: It was great that they released it, but they didn’t know how to connect with the ’60s collector types. This new release on World in Sound is much more targeted at that, so it should get more attention this time around.

‘Gift’

Roger: Immediately after Freak Trio Electric, we did a lot of drawings—basically, a massive creative outburst. I did a series of them based on the “Toke Mythology.” We 100% believed that weed was why we were doing what we were doing—an obvious fallacy in hindsight, but it certainly affected us that way at the time! The drawing referred to in this song shows the three of us bringing a gift to the Toke God, which appears from behind a stylized mountain.

‘Pretty Pictures, Now’

Roger: The main riff I came up with in the fall of 1968, but didn’t know what to do with it. Very quickly after we recorded Freak Trio Electric, the song came together and was brought into the new band. I saw the giant leaves on a tree in the Arboretum while I was tripping, and it clearly made an impression on me!

‘In the Sun’

Roger: The main riff owes a definite vibe to the first Silver Apples album, which we listened to relentlessly. I wrote it in February 1969, a month before Freak Trio Electric. I tried it out in my power trio band Factory, but they just couldn’t figure out what to do with it. Playing a straight rock beat made no sense, and it took Freak Trio, with Lar’s unusual approach to beats, to bring this song to life.

Ben: This song was one of my favorites. The verse riff is amazing.

Laurence: I always liked the bizarre guitar riff on this tune. Twisted in the correct measure. As a drummer, I tried simply to follow it.

‘Sister Regis’

Roger: Our “At the Playgrounds of Olympus” session had produced a ‘Chant for the Easter Eggs.’ We chanted “Easter Eggs” over and over, and when we came to the end of the chant (of course, we did not prepare this ahead of time—it was 100% spontaneous), that phrase had morphed into ‘Sister Regis.’ This phrase immediately achieved mythical proportions for us, and I wrote the song the next day. It was only later I realized that “Regis” means “of the King” in Latin, which I had studied a bit in high school. That Sister Regis meant “Sister Regis, sister of the Wizard King of Tokes” was an obvious development in hindsight.

Laurence: I always enjoyed playing this song. It had an awesome trumpet solo. Very relaxed, and without a doubt, the most “pop” sounding track.

‘Bush’

Roger: A light summer 1969 song, very much in the vein of Syd Barrett’s fantasy songs. Lar and I had a duo at that time, while the full Freak Trio was on hiatus. We did this one and others that each of us wrote. This was the only one of those songs that made it onto the album.

Laurence: Yes, I recall playing songs like this with Roger throughout the summer of 1969 using acoustic guitars. I can’t recall how and why that came about, but I understand now it was largely due to the fact that we didn’t have any rock equipment to continue as Freak Trio. (Roger’s friends apparently took their gear back.) I wrote a few songs then, too—like ‘The Ozone Came Alive’ and ‘On My Hill.’ Roger and I sang together very well.

‘Tidal Wave’

Roger: Like ‘Nocturnal Mission,’ this has a “warp theme” as an introduction before the main body of the song begins. One of the riffs in this section came from the Freak Trio Electric session, transcribed to fit the song. The lyrics to this one are among my favorites in Sproton Layer. There is a double-death here which is quite curious, very dream-like. The situation is that a king has died, and a solemn procession is carrying the casket down a canyon to the seashore for burial. But they cannot see that in the distance, a tidal wave is coming, which will destroy the entire mourning party as well as the dead king. The narrator sees this from his position on top of the canyon, but can’t warn them in time.

Laurence: Roger’s songwriting was expanding. The beginning of this tune runs at a frenetic pace with interesting harmonic movement, though very short. While the bulk of the song borders on being tedious, in my humble opinion, it is nonetheless powerful with a great lyric.

‘Up’

Roger: A rather straightforward, positive song. The melodic middle instrumental section really achieved a “lift-off” emotionally, especially live. It would carry us away.

Laurence: Another one of my favorites, full of hope. By the end of the song, all I’m doing is pounding out the downbeat—kick, snare, cymbal. What else was there left for me to do?

‘The Blessing of the Dawn Source’

Roger: A bit pompous, but I was not even 18 when I wrote this. Teenage angst combined with a psychedelic-induced search for greater meaning. Ben wrote the last section, the chord progression that gets more complex each round. The opening is a direct quote from Dvorak’s New World Symphony, which I always liked.

Laurence: Again, I shied away from playing traditional backbeats whenever I could. So, it was always a bit unnerving for me on this song as I broke into the typical rock groove during the guitar solo. Great song, though.

‘Nocturnal Mission’

Roger: Kind of a hypothetical acid experience, about getting off on acid, somewhat mythologized. What balances the slightly over-wrought acid ideal is the brief “chorus” just before the great guitar solo by Ben. The lyrics “I can tell you why but please don’t ask!” add a nice ironic levity to the proceedings, in my opinion! The brief introduction is also classic Sproton Layer—zero blues-based chord progressions, with riffs that are chromatic and whole-tone based. We called them “warp themes” in those days—we weren’t aware of the actual harmonic content, just that it sounded great to us.

This non-rock harmonic content is obviously influenced by the U of M Contemporary Directions concerts that we were attending.

‘Point of View’

Roger: Me trying to figure life out (I was a late bloomer). I’m fond of the structure on this one: all sorts of unexpected ins and outs, with the trumpet pretty integrated. But it all adds up and makes its point. Everything might be Real.

Ben: I enjoy the 20th-century music ethic of this piece.

Laurence: This is one of my favorites. Truly advanced songwriting.

‘New Air’

Roger: Lyrics were from two different stoned experiences, with a bit of “hope for the future” thrown in for good measure! Similar structural complexity as “Point of View” (written a couple of months apart), with a rather devastating “destruction solo” by Ben and truly superb free-form drumming by Lar in the introduction section.

Ben: I enjoy the 20th-century music ethic of this piece.

Laurence: Another favorite of mine. Remarkable.

‘The Wonderful Rise’

Roger: Another late teenage angst song. The waltz at the end is pretty weak melodically, but the sound of it could be construed as rather charming. I doubled the piano as an overdub during the vocal take. The “magic pets” were weed and the psychedelic experience.

There’s also a single with three songs.

‘A Lost Behind Words’

Roger: Written in May 1969, when the band had only been together for a couple of months. The title and lyrics were from a brief internal acid vision. I was walking with some friends and was having trouble communicating. In my mind, I saw a 3-dimensional “WORD,” sort of ‘Yellow Submarine’ style, and behind it was a shadow of a person. “I can see a human shadow there—lost behind a word.” One of the middle parts was from the early Freak Trio Electric session that started the band: I transcribed it and organized it a bit. It helps give the piece an organic flow rather than a typical “song structure.”

Ben: My favorite released song thus far. Great lyrics on severe alienation.

Laurence: A well-described psychedelic experience where thoughts and feelings rise far beyond the spoken word.

‘Space Red’

Ben: This is a song I wrote myself, where I tuned the A string down to be unison with the low E string. After the solo area, when the non-vocal verse begins again, the guitar slides up at the very end of the riff while the bass guitar slides down simultaneously. Sonically speaking, there’s a “ripping” effect. I wrote a couple of other songs for Sproton Layer with lyrics, which were rehearsed but were never quite up to snuff to record or perform.

Laurence: Great and fun piece to play. It was nice as a departure to be purely instrumental—no lyrics.

Roger: Ben’s first piece in the band. Not complex, but it’s a ripper live.

‘Jam From Outer Space’

Roger: This was a collective improvisation from December 1969. Ben and I doing the rather funny vocals at the top. This element was mostly dropped by 1970—crazy vocals influenced by early Pink Floyd’s ‘Pow R. Toc H.’ We often decided on a mood or title before an improv, which would help steer the improv.

Ben: This is an example of our “Space Jam” approach. Like free-jazz; this was free-rock. Sometimes we had specific mindsets to work from or set up paintings in front of us to get ideas, much like Romantic music would use Nature to express musical ideas, but more often, we would simply start playing and see what came up. Our general frame of mind was to produce ideas quickly and follow them without expectations and without concern for chord progressions or any of the usual techniques that most rock bands used.

Laurence: Perhaps not the best example of our free-form mayhem, but certainly a classic.

World in Sound re-released your material.

Roger: The 20-page color booklet was an amazing gift from Wolf. We could not have asked for more. The mastering job they did in Germany from the master tape I had is a vast improvement over the New Alliance release. So the answer is a resounding YES.

Ben: Very satisfied. The production value of this reissue and the mastering finesse are far superior to the original SST release. Good job, Wolf! The overall sound seems well-mixed, perhaps for the first time. Somehow, the vocals sit better in the mix, and I really dig the bass sound.

Laurence: Three words. YES AND YES.

We will be doing a second album with World in Sound. There are six or seven unreleased songs from earlier recording sessions (1969), and some defining improvisational sessions (1969 and 1971). The album is tentatively titled ‘Press Your Hand and the Whole Room Fluctuates.’ Not sure about the release date, as we have just drawn up the basic plan, but probably within a year or two. We are quite excited about it, as the material, while less polished, covers some different territory than ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted.’

Any crazy stories you would like to share?

Roger: It wasn’t super crazy or anything. Mostly, it was Lar, Ben, and I just being hyper-creative, following whatever ideas came up, and, being teenagers, a little bit confused!

Our best shows were ones where we played two sets of originals, then toked up and played a third set of free-form Space Jams/improvisations. At one of these gigs on the University of Michigan campus, we took time off and learned our song ‘Yellow Balloon’ backward! It took us about 15 minutes to work it out (while smoking a joint, I suspect). I sang the vocals in a faux backward delivery, following inversions of the melodies as closely as I could. When we got to the end of the song—in reality, the beginning of the song—we all burst into laughter! It was quite an accomplishment. We had a tape of it, but unfortunately, it got lost.

Another memorable one of those events was our third Space Jam set at the Milan Community Center. We planned the opening jam out this time. We started with a straight boogie/blues jam and gradually, hopefully imperceptibly, morphed into totally atonal Space Jam warps. I recall people being generally confused/bemused by it.

The ideal gig that we fantasized about was us opening, Captain Beefheart and His Magic Band in the middle slot (‘Strictly Personal’ era), and Pink Floyd (‘Piper’-era) as headliners. Those were the type of sounds we thought we were related to.

Ben: We were too young to have crazy band stories.

Laurence: As fairly respectable youngsters, we weren’t into the “fucking in the streets party scene.” We kept to ourselves mostly, simply getting high with our best friends. The early part of 1970 was rough for me, though. I was suffering from depression and flights of fancy and had to seek psychiatric evaluation. It was later deduced that both Roger and Ben might have also qualified for psychiatric evaluation. But yeah, outside of a couple of incredibly imaginative experiences together (employing our inner children the size of Texas), and yes, a few bad acid trips, I’d say the wildest trouble we ever got into would be setting up a croquet game in a churchyard with friends at around midnight. Cops showed up to tell us to stop. That’s about the size of it.

What happened next?

Roger: The times were getting conservative, and “partying” was taking over the “ideas” in music. We just didn’t fit. We got no interest from booking agents or people we thought would be sympathetic. Nothing whatsoever. We folded in the fall after getting no response. We got back together sporadically in 1971 as an all-instrumental band that actually produced some interesting Space Jams, but it was very haphazard, and we only played a couple of shows for friends’ events.

There was one very odd good thing that came out of the recording at that time, though. In late fall 1970, a friend of mine had been contacted by a woman who had an anthropological grant and was studying rock music. Her name was Gertrude Kurath, and she was in her 60s. My friend referred me to her, and I loaned her our tape to hear fuzz tones, wah-wahs, etc. Literally an hour after I loaned her the tape, she called up completely worked up—she was blown away by ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted.’ She had a Wenner-Gren Anthropological grant to write a book about rock and roll, but she said then and there that she wanted the book to be the complete scores for ‘WMFD.’ I was rather stunned because I’d already given up on this! She paid me $200 to type out the lyrics, notes on each song, and hand-scribe the complete score for every song. So, for quite some time, I sat and listened to the recording, writing out each guitar chord and strum, bass part, trumpet part, drum parts—snare, kick, tom-toms, high-hat, etc.—and vocals in full-score’ form. Kind of insane. I believe this may be one of the very few examples of entire rock scores having been written out.

The book came out in 1972 on the Ann Arbor Publishers imprint—I have no idea how many were printed, and neither Gertrude Kurath nor I made a single royalty from it. Ann Arbor Publishers has long since defunct. But the book did come out, with my notes and scores for every song, plus some photos and related drawings, and an introduction by Gertrude Kurath. You could even order a copy of the tape from instructions in the book—I guess a few copies were sold, but I don’t really know. So, despite the Ann Arbor hippies not giving a shit about us, this eccentric elderly woman gave us some support via an anthropological grant. A rather odd situation, I must say!

It wasn’t until I was on the New Alliance label (affiliated with SST) and I suggested that they release it (1991) that anyone other than a very, very few friends had heard the album.

Ben: Sproton Layer folded shortly after the recording of ‘With Magnetic Fields Disrupted.’ We tried to return to our original energy in 1971. Since we had sold our PA system, it was only an instrumental band without Harold on trumpet. This version of Sproton Layer played a couple of parties and fizzled out with no recordings of new material other than some space jams. I did write a few more songs in 1972 with the hope that we would reform. If by some extreme quirk Sproton Layer returns to action in 2012, I would surely include those in our 21st-century repertoire!

Laurence: I moved to live with my older brother, Gifford Miller, in Colorado for the first part of 1971. I went to high school there. I moved back that summer and soon began experimenting with drugs again, this time using LSD more frequently. The three of us did get together again for a short stint that year. Very interesting results with improvisation, but nothing very concrete came of it. That was it.

Formation of Mission of Burma followed. Your debut is among the best in the genre.

Roger: Glad you like it. I find the following comparison of Sproton Layer and Mission of Burma very interesting. A trio is the ideal ensemble (to me, anyway!) for freedom and fullness of sound, and this was the basis for both Sproton Layer and Mission of Burma. But “a little more variety” was needed—in the case of Sproton Layer, it was a trumpet that didn’t play on all the songs. In the case of Mission of Burma, it was tape loops that weren’t on all the songs. And, for my part, there are many similar directives in the songs I wrote for both bands. Unorthodox structures, lyrics that were more related to dreams or “poetic” rather than “rock and roll,” a blending of avant-garde techniques and form, etc. In many ways, the ideal/archetypal model in Sproton Layer is the same model that ended up as Mission of Burma. The primary difference is that Sproton Layer was in the psychedelic period, and Mission of Burma was in the post-punk period. At least, that’s what I think at the moment!

You are also part of Birdsongs of the Mesozoic.

Roger: Birdsongs of the Mesozoic started off as a one-off gig/band that I put together for a benefit, after Erik (Lindgren) had offered me his studio to record some of my piano pieces (the prototype of the band). I’ve always had a push-pull thing between guitar and piano (I play both), and this band vs. Burma is that manifestation at the time. Ultimately, the rhythm machine was a flaw in Mesozoic, but it helped keep the volume down, which allowed the band to continue after Burma folded. We often played rock clubs, and in that sense, we certainly broke down a lot of barriers!

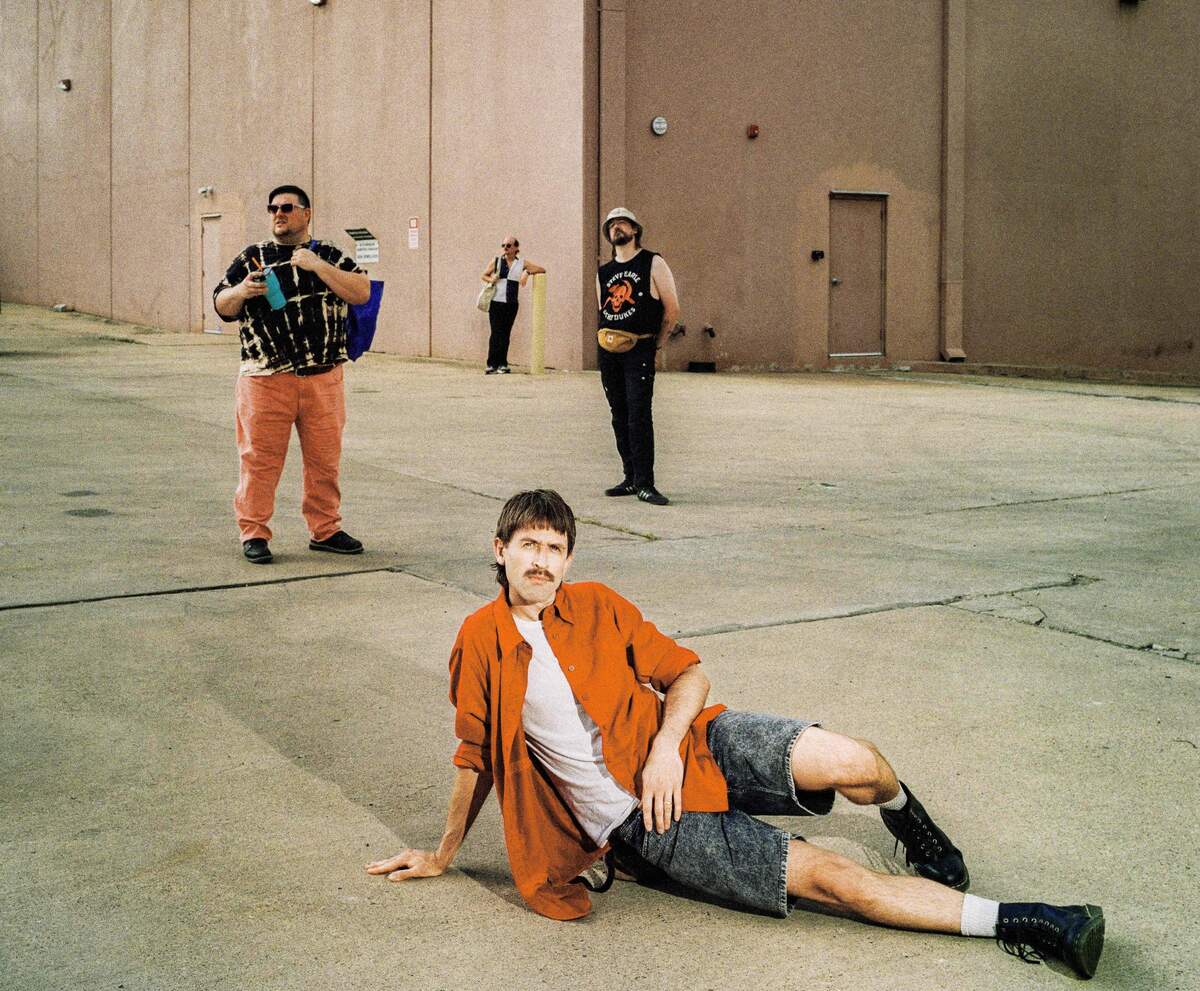

Later you were part of The Space Negros, No Man, Moving Parts, M3, Alloy Orchestra, Binary System…

Roger: M3, of course, is Lar, Ben, and I many years later! Some of it is quite interesting, but since we live in different cities and are more of a recording project than anything else, we haven’t produced anything as fully developed as Sproton Layer. However, I like both the albums we released quite a bit. The first, ‘M3:M3,’ on New Alliance (the same label as the first Sproton Layer release), is quite deconstructed but has “songs” as well as sonic experiments; the second, ‘Unearthing,’ on Sublingual Records, is extremely deconstructed—all very experimental instrumentals, with some occasional reference to rock music.

I made three records—two on Ace of Hearts, one on SST, released between 1986 and 1990—of what I called ‘Maximum Electric Piano.’ This activity started in 1983 when I got an early looping device—the Electro-Harmonix 16 Second Digital Delay (different from the current one they make). I applied it to a Yamaha Electric Baby Grand Piano that had strings. I did prepared piano and ran the piano through fuzz tones, etc., like a guitar. I played directly on the strings at times. First, I’d set up prepared piano loop grooves, then play compositions/songs over that, often changing things up considerably as I went along. Basically, I invented an instrument/ensemble. Many people are now engaged in maximizing one instrument via loops—I was actually doing this in 1983. I consider it to be one of my more interesting behaviors.

The Binary System was me on piano/prepared piano with a rather exceptional drummer, Larry Dersch. We recorded an album on SST, and two albums on Atavistic. The second album, ‘From the Epicenter,’ I really think is quite a good album. You can still buy it from them on their website. A very dynamic duo, it’s an all-instrumental blend of improvisation, rock beats, modern classical structures, and prepared piano. A bit like what I was working on in the Mesozoic, but with much less of the Terry Riley/Philip Glass minimalist thing. Because Larry’s drumming is so great, I actually feel this band accomplished its goals in a better fashion than my work in the Mesozoic.

“Psychedelic isn’t a time zone; it’s a state of mind”

What currently occupies your life?

Roger: I am still active in Mission of Burma. We will complete a new album early in 2012, and we are currently deciding between two labels. It’s pretty dynamic, we think.

I am also active in the Alloy Orchestra, a trio that accompanies silent movies live. I have been in this band for nearly 15 years, and we tour all over the U.S. and sometimes Europe, playing film festivals and theaters. Roger Ebert says, “Alloy Orchestra is the best in the world at accompanying silent film.”

I do various improvisation work, most recently with Ben in M2. He (multiphonic guitar) and I (prepared piano) recorded an album recently and are looking for a label to release it. It’s very experimental/ambient, and I think it’s one of the best-sounding records I’ve ever been involved with.

I have also picked up where I left off as a composition major at the California Institute of the Arts (1976). One of my new compositions was recently performed at the New England Conservatory (for viola, piano, percussion, and musique concrète). I am working on other compositions in this style—the second one is for two string trios, electric organ, and three percussionists. I am also working on music based on frequency analysis of creeks in California and Vermont.

Ben: I am composer and conductor for The Sensorium Saxophone Orchestra, NYC’s first full-on saxophone orchestra. We have 20+ members ranging from bass to soprano sax, with two drummers. Most of our material is fully notated using a unique method of my own based on interval sequences. We will be releasing Terry Riley’s ‘In C’ and a recording of my first symphony in 2012.

I’ve been playing solo shows since 2000 using a deconstructed multiphonic guitar. I also explore alto saxophone through various treatments in a similar vein of theoretical cacophony. Several releases of this type are out on the following labels: Living, Gulcher, Tigerasylum, Obsolete Units, and Feeding Tube.

I had a rock band in NYC with drummer Jarrod Ruby and former Phantom Tollbooth bassist Jerry Smith from 2003 to 2010. Third Border’s first (Living Records) and second release (Radial Records) had a psychedelic tinge. Our third and final release had more angst.

Laurence: Like Ben, I have continued over the years in original music bands since Sproton Layer broke up. From “unplugged” folky stuff to avant-garde classical/jazz to Noise Bands before such a term was coined. One of my favorite bands was a fringe group I called Empool—psychedelic noise improv and almost all instrumental. Empool melted into Destroy All Monsters in 1977, and the rest is history. As for my current work, I reinvented myself 12 years ago as Mister Laurence, a children’s performer. I’ve since released a handful of solo CDs and produced award-winning music videos. Two years ago, my wife came on board playing keyboards and singing. She helped expand the whole idea by bringing in an animatronic bear she built to play the drums. True entertainment for kids of all ages. We call ourselves, with tongue in cheek: The Mister Laurence Experience.

Would you like to send a message to the readers of It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine?

Roger: Psychedelic isn’t a time zone; it’s a state of mind.

Ben: Get Sproton Layer a record contract and touring agent! If I had my way, I’d drop everything I’m doing musically right now and return to what was possibly my first passion: psych-rock songwriting and Space Jams.

Laurence: Yesterday, plus tomorrow, equals today.

Klemen Breznikar

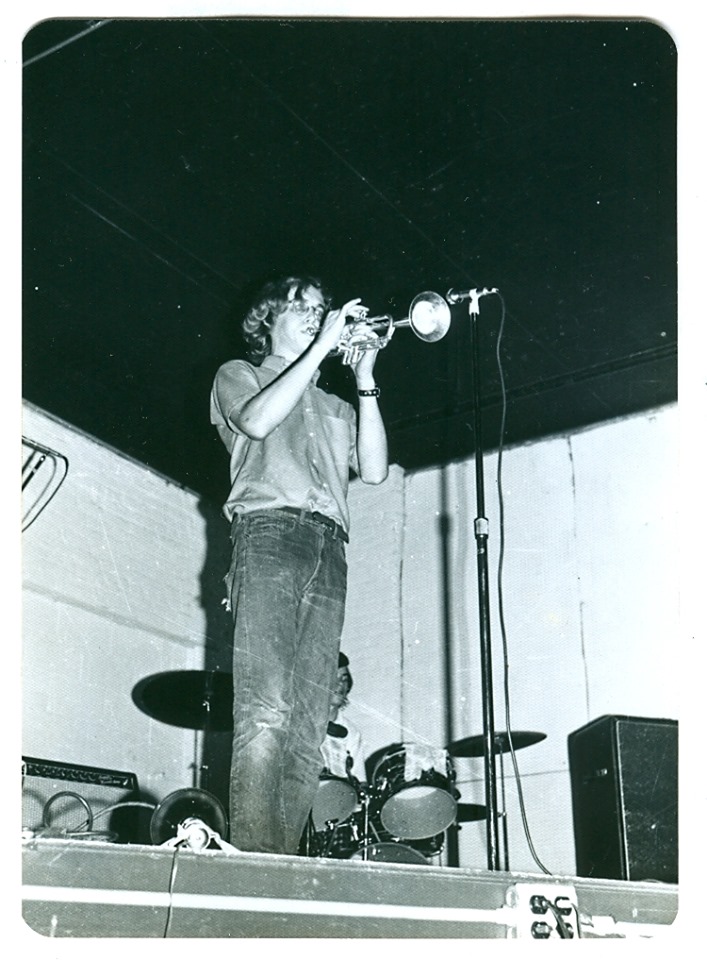

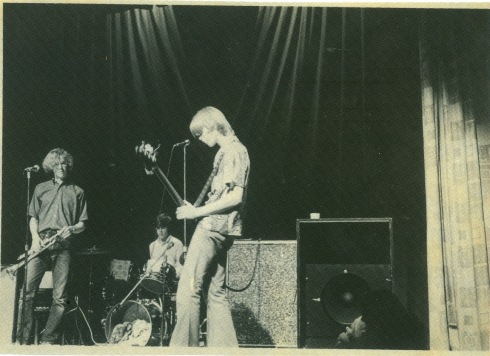

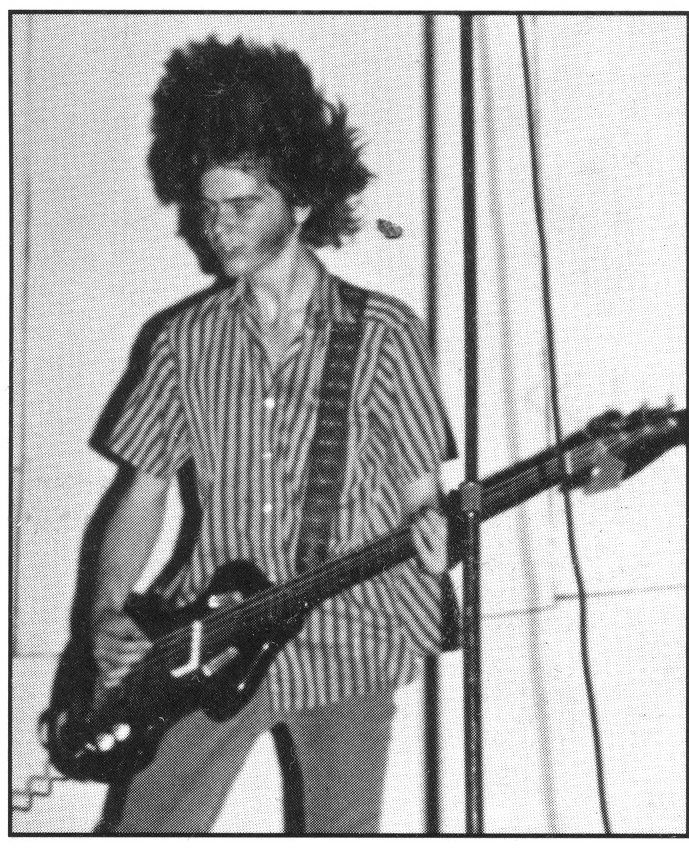

Headline photo: Sproton Layer (Lar on drums at the Big Steel Ballroom, July 1970.)

Roger Miller Official Website

Laurence Miller Official Website

Ben Miller Official Website

I have fond memories of playing with the Miller brothers in Boston during 1972-74. Larry,Ben and I were in a couple bands. (Nova Mob,Cruzonics) I have many cassettes of the group and at least one that includes Roger. They had a unique self taught system for writing out tunes and they always wreaked in originality while having a scent of various influences from around the Ann Arbor/Detroit area and of course other universes. I always enjoy their current projects as well! Glad to see this article here! Don Davis (Microscopic Septet)

I have fond memories of playing with the Miller brothers in Boston during 1972-74. Larry,Ben and I were in a couple bands. (Nova Mob,Cruzonics) I have many cassettes of the group and at least one that includes Roger. They had a unique self taught system for writing out tunes and they always wreaked in originality while having a scent of various influences from around the Ann Arbor/Detroit area and of course other universes. I always enjoy their current projects as well! Glad to see this article here! Don Davis (Microscopic Septet)

three headed dog!

most entertaining