Van der Graaf Generator | Judge Smith | Interview

Judge Smith is an English songwriter, author, composer and performer, and a founder member of progressive rock band Van der Graaf Generator.

Judge Smith co-founded the influential rock band Van der Graaf Generator in 1967 with singer-songwriter Peter Hammill, and since then has continued to be involved in numerous musical projects as writer, composer or performer. During the ’70s and ’80s, he wrote several stage musicals in collaboration with composer Max Hutchinson: ‘The Kibbo Kift’ was produced at the Traverse Theatre for the Edinburgh Festival of 1976 and at the Crucible Theatre, Sheffield the following year. ‘The Ascent of Wilberforce III’ was produced at the Traverse Theatre in 1981. Their musical ‘Geraldo’s Navy’ was commissioned and accepted by Michael Rudman and David Aukin of the Hampstead Theatre Club, but not staged. ‘The Ascent of Wilberforce III’ received a second production at the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith in 1982. Later the same year, the Lyric also presented ‘Mata Hari’, a music-theatre piece he co-wrote with (and which starred) singer Lene Lovich.

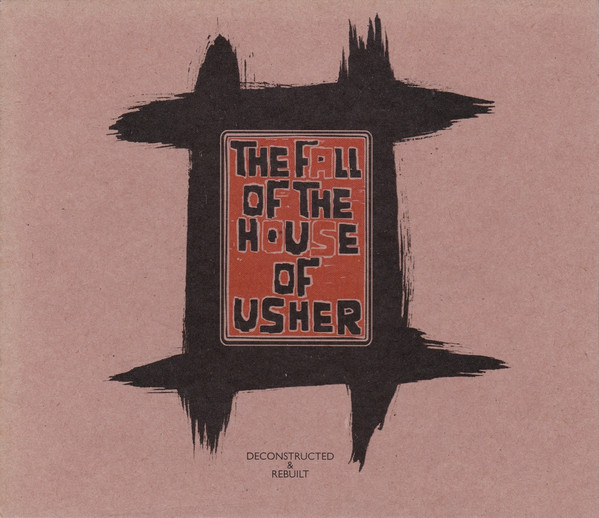

As a librettist, his works include the text for classical composer Joseph Horovitz’s oratorio ‘Samson’, premiered in a radio broadcast from the Albert Hall in 1977, short texts for works commissioned from the same composer by ‘The Kings Singers’, and the libretto for composer Michael Brand’s cantata ‘Pioneer 10’, performed at Birmingham Symphony Hall, 1992. Following a twenty-year collaboration with composer Peter Hammill, their opera ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ was finally completed, recorded and released in 1992, and in 1999, a revised and re-mastered recording was re-released on Fie! Records. More recently he wrote the lyrics and libretto for ‘Twinkle’ a large scale children’s piece by David Jackson, and contributed lyrics to another of that composer’s works for children, ‘The House That Cried’. His chamber opera ‘The Book of Hours’ was directed by Mel Smith at the Young Vic Theatre, London in 1978. His short film ‘The Brass Band’, which he wrote and directed in 1974, has won several international awards. His songs have been recorded by Peter Hammill and Lene Lovich and featured on the early ’80s TV comedy show ‘Not the Nine O’Clock News’. He has released several albums. Some of the most prominent among these are the three albums written in the “Songstory” format which he has developed as a new form of narrative rock music: ‘Curly’s Airships’ (2000), ‘The Climber’ (2009), and ‘Orfeas’ (2011). His Requiem Mass for Rock band, Choir and Brass was written and published in 1975, but was not recorded until 2016. In 2013 CFZ Press published his first book, ‘The Universe Next Door’, and a further book on spirituality and the paranormal was published in 2014.

“My best music has come to me from nowhere”

What were your first musical involvements?

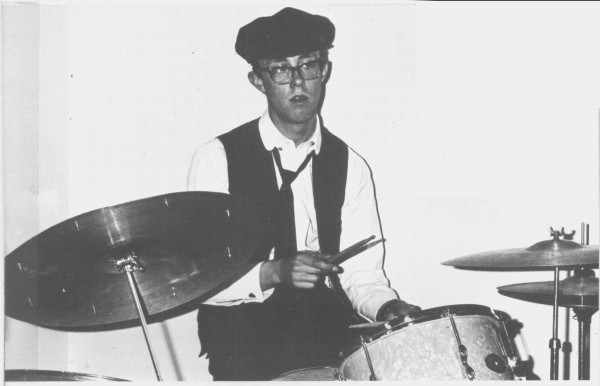

Judge Smith: At school I played drums in a pretty awful Trad jazz band called The Gut Bucket Stompers. Maxwell Hutchinson, a future collaborator, played upright bass. I also wrote a song or two for the band. ‘I’ve got the Nasty Pasty blues (they keep repeating on me…)’ comes unpleasantly to mind. Max and I also used to sing songs off the first Bob Dylan album.

Otherwise, I was an avid listener to ‘Pick of the Pops’ with Alan Freeman; a pop music consumer with no ambitions to be a pop music creator. I wanted to make films.

My father was an avid Jazz fan; mainstream modern jazz of the ’50s & ’60s and I absorbed a lot of music from him. He would take me and Max to the original Ronnie Scott’s Club in China Town and, by the time I was 16, he would give me a fiver and let me go off to Ronnie Scott’s on my own.

Who were your major influences?

When I left school, I crossed the Atlantic on a cargo boat with a friend, and we went round America by Greyhound bus. We ended up in San Francisco; so this is 1967 “the summer of love”, Height Ashbury, the whole hippy scene. I was able to see most of the great West Coast bands of the time, and realised that rock music could do extraordinary things and go off in strange directions, and was worth taking seriously as an art form.

How did you first get in touch with drums ? What in particular fascinated you to begin playing this instrument?

I only tried to be a drummer because it seemed easier than playing anything else. I have no instrumental ability whatsoever. I can’t strum a guitar, and, after half a century of using a keyboard, I still have little balls of Plasticene to show me where to put my fingers.

I was a very poor drummer indeed, and wanted to sing instead, but it took me years to learn how to do that.

“Peter Hammill and I were particularly knocked out by The Crazy World of Arthur Brown”

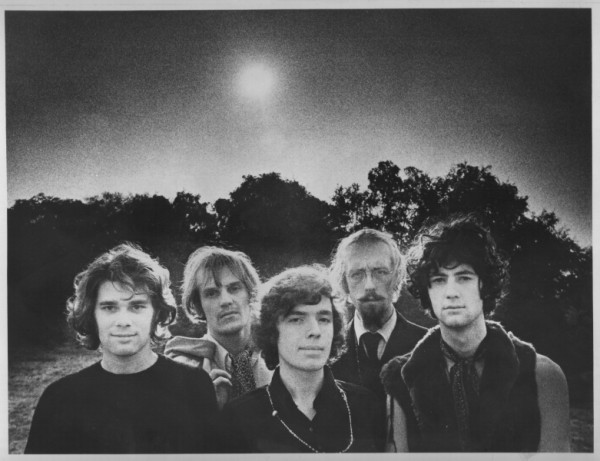

Where did you originally meet Peter Hammill? What led to formation of Van der Graaf Generator?

We were both first year students at Manchester University. A notice went up in the Student Union inviting anyone interested in forming a band to a meeting, and a large collection of wannabe rock stars turned up. Peter was strumming a guitar in a corner and singing what I thought was a wonderful song, and the song turned out to be by him, so I thought “he’s good, I could be in a band with him”. He also looked the part, which I didn’t.

We got to know each other and went to a lot of gigs. The Union put on some astonishing acts at the time, and I saw Hendrix, Cream, Pink Floyd (at another Manchester college) and Stevie Wonder. However, Peter and I were particularly knocked out by The Crazy World of Arthur Brown, and this inspired us to try and be an organ-based band, rather than a guitar, band. Unfortunately, the friend who wanted to play organ with us didn’t have an instrument, so Peter and I performed for a while as a duo, with Peter on acoustic guitar and me playing percussion, whistles et cetera and doing rather dodgy backing vocals. It worked okay because Peter’s early songs were just so good.

What sort of venues did Van der Graaf Generator play early on? Where were they located?

We both left Manchester after our first year because we had landed a record contract, but while we were still there we played various student venues, and a club in the city centre called “The Magic Village” where we played support to various combos, including Tyrannosaurus Rex and The Third Ear Band. Neither of these were very friendly; Bolan seemed to think we had copied his two-person format, while the spookily serious Third Ear Band thought we had “ruined the vibes” for them with Peter’s essentially sunny material (as I have said somewhere before, it was probably the last time anyone accused Peter Hammill of lacking seriousness.)

The club had a sort of resident drummer, Bruce Mitchell, later to play in the Durutti Column, and it was when watching his solo workouts, I think, that I realised that I was never going to be a decent drummer.

Once we came down to London, we mostly played in an audition or showcase setting, rather than actual gigs; playing, still as a duo, to record company people, and, memorably, to John Peel, who then wrote kindly about us in his Melody Maker column. I do remember we used to play in Hyde Park a bit for fun. On one occasion we were enthusiastically accosted by the Hollywood actor Lionel Stander, who wanted to be photographed with us picturesque hippies, and on another occasion, less enthusiastically, by the police, with the memorable words, “You can play that outside the Park, or inside the Nick…”

How did you decide to use the name ‘Van der Graaf Generator’?

This was one of a list of potential names for a band I had made on my journey home from the USA. I think my favourite was “Zeiss Manifold and the Shrieking Plasma”, but eventually we chose, perhaps wisely, “Van der Graaf Generator”, a miss-spelling of the real scientist’s name, by the way. Strangely, several of the other names on my list actually also became the names of real bands as well.

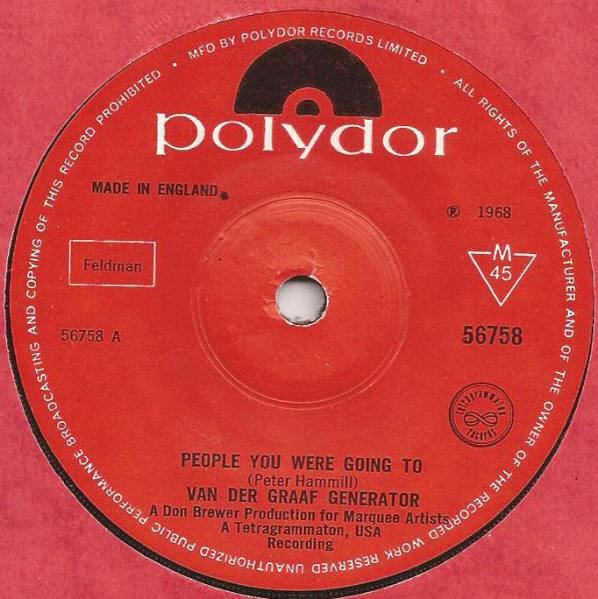

You only played on ‘People You Were Going To’ b/w ‘Firebrand’ and then left the band in 1968. What do you recall from this single and what followed?

At this point, we had recruited Hugh Banton on organ, and Guy Evans to replace me, on drums, with my enthusiastic agreement, I might say. I was relegated to weird supporting instruments and backing vox. I was quite pleased with ‘The People You Were going To’, as I had a chance to play my Slide-Saxophone, a rare and bizarre Victorian instrument that looked like a soprano sax which had been stripped naked and strapped into a sort of surgical appliance.

I was less happy with ‘Firebrand’; a great song, but I had unwisely decided to try and emulate my hero Arthur Brown on my bits of solo vocal, with decidedly dubious results. Many years later, I became friends with Arthur and was lucky enough to get some singing lessons from him, and over the years, I have learnt to sing like me, and not like anyone else. It does seem to be a somewhat unique vocal style, but I like it, and I now claim to be the best Judge Smith-style singer around.

We soon recruited Keith Ellis on Bass, and Peter began to lead the band into some astonishing new musical territories. Judge, with his Ocarinas and hand percussion, really didn’t have a place in this powerful, heavy, entity that was emerging. And, with Peter’s songwriting developing so fast, my lyric writing abilities were no longer required. So I gracefully retired from the band. Though everyone was very positive about my presence, at some point I would have been pushed.

You went on to form a jazz-rock band called Heebalob, which included saxophonist David Jackson. Tell us about it.

My school friend Maxwell Hutchinson was now an architectural student in Aberdeen and had a rock band called Cousin Mary. I went up there to guest as vocalist on a couple of gigs, and joined them on a bizarre expedition to Portsmouth for a conference of architectural students where Cousin Mary was to be the resident band. We took a gig venue with us in the form of a collapsible geodesic dome they had constructed. It was rainproof, but not soundproof, so the local constabulary were not at all pleased by our blues-rock stylings.

Maxwell and fellow architecture student, drummer Martin Pottinger, decided to join me in a new band with bass-player John Weir and, for a short time, guitarist Steve Robshaw. On Steve’s departure, his place was taken by a friend of Max’s, the saxophonist David Jackson. We wrote a set of quite complex jazz-rock strangeness, but truthfully, we weren’t really up to making a good job of it from the technical point of view. Max was a vigorous rhythm guitarist and a highly eccentric soloist on guitar, piano and sax, but only David Jackson could really cut it as a professional muso.

Our first gig was at the 1969 National Jazz and Blues Festival at Plumpton (the following year it became the Reading Festival, I believe.) It seemed to go okay and we were spotted by Giorgio Gomelsky who had managed the Rolling Stones and the Yardbirds, and had his own record company, Marmalade. He wanted to take us on and was prepared to pay us some wages while we rehearsed. He also recorded demos of our set at Polydor Studios, off Oxford Street.

We called ourselves Heebalob with the idea that the word represented the sound of the modern free jazz we all enjoyed, in the same way that Bebop represented the phrasing of the Charlie Parker-era jazz of the ‘40s. This was not a good band name!

Unfortunately, the day I went in to the Marmalade offices to pick up our first pay-cheques, I found secretaries emptying their desks and a furniture van removing everything else, since the company had just gone bust. That was pretty well the end for Heebalob.

Then you pursued a solo career, and wrote and recorded many songs. How do you usually approach songwriting? Is your material set in stone by the time you record, or is it an ever-evolving process?

I’ve had a long life as a maker of stuff, and managed to produce sixteen albums and DVDs, a play, a movie, various libretti, four musicals and a book, but I don’t work fast. When it comes to music I am slowed down by my lack of conventional musical skills. I find I can easily imagine complex music, but I have to grind away at bringing it into the physical universe. My best music has come to me from nowhere, out of the ether, and doesn’t feel as if I have written it at all, and early on I developed the discipline of recording immediately any tunes or riffs that came to me, by singing them on to short cassette tapes, of which I now have hundreds. I’m still dipping into material that might be decades old.

I didn’t really start to record my own music to a good standard until I was over 40. Until the 1990s, the technology was just too expensive for me to achieve anything better than demo tapes, but I eventually acquired a newly developed 16-track, half-inch tape recorder and an analogue mixing desk, an early digital sampler, an equally rudimentary sequencer, and all the attendant gubbins, and learnt how to use them, after a fashion. The technical process has steadily become easier and more affordable as time has gone on. The digital revolution has been very good for me.

I tend to make my recordings by playing or programming whatever I can myself, including my vocals, and then adding rough or demo versions of what I would like other instruments to be doing, and then get musician friends to replace those rough tracks with their own performances. I love what other ears and other hands can bring to a song, and I always try to stay open to different ways of looking at a bit of music that might have already become very fixed in my mind. On the other hand, I’m not exactly democratic; it’s my stuff, and ultimately it will get done my way.

From the outset, I recorded my tracks in whatever “home” studio I had put together at the time, and then would go to a professional studio that had an accomplished and creative engineer, to mix them; a procedure I use to this day. This seems to be the right compromise for me between D.I.Y. and commercial music making. Mixing is a black art, and I much prefer for someone else’s hands to be on the faders. I sit on the sofa and say it needs more cowbell.

It’s absolutely impossible to cover your discography. Would it be possible for you to choose a few collaborations that still warm your heart?

I couldn’t possibly chose any albums of mine as being favourites. It may be silly, but I’ve never had any children, and I regard my albums as somehow being my offspring. I love them all equally, I really do, with all their faults, and they all still warm my heart despite the fact that they are all very different from each other. Interestingly, I don’t believe that even the early ones have dated to any great degree. They are strange and unusual enough to be outside the established styles and sound-worlds of whatever period they appeared in.

This may all seem very arrogant and self-satisfied on my part, but I think that all Art is, to some extent, egotistical. However personally modest the artist may be, their work, simply by announcing itself as an artwork, says “Look at me! Listen to me!”. And if the artist is working out on the fringes, without a lot of popular or critical support, he or she really needs to have a very healthy dose of pride and self-esteem just to keep going.

What’s the story behind the last three albums, ‘The Solar Heresies And The Lunar Sequence’, ‘Towers Open Fire’, ‘Music From The Garden Of Fifi Chamoix’?

I’ve been interested for some time in the various ways in which speech (spoken language as opposed to sung language) can be combined with music, and I first experimented with one type of combination in ‘Orfeas’. The two long pieces that make up ‘The Solar Heresies And The Lunar Sequence’ each use different techniques of combining speech and music (although there are also a few short bits of singing in ‘The Lunar Sequence’.)

‘The Solar Heresies’ is an important achievement for me. The spoken text is a sort of metaphysical tract that came to me quite spontaneously, within the space of an hour, while I was in Udapur in Rajasthan. It was never intended to be set to music, but having composed ‘The Lunar Sequence’, I could see that a version of ‘The Lunar Sequence’ in a music and speech format would also work wonderfully well with my lunar work as a companion piece. I am lucky enough to know the brilliant Prof. Ricardo Odriozola of the Grieg Institute, the conservatoire of Bergen in Norway, who likes my music and agreed to arrange my piece for a chamber orchestra, which we recorded, there, in Norway; a wonderful experience for me. ‘The Solar Heresies’ is a serious mystical work, but I hope it sounds quite light-hearted. As I have said elsewhere, the Tragic Muse has never got much traction with me.

Over many years, I had written various texts or meditations about the full-moon and these came together to form the lyrics for ‘The Lunar Sequence’, with the addition of a verse by Ben Jonson from 1601. (The ‘Sequence’ refers to the succession of phases of the moon). Musicians on this piece include four fine artists from the Glastonbury music scene and a heavy-metal guitarist from Liverpool, while the “voice artists” include my old friend, 1980s pop star Lene Lovich, my even older friend, Nick Lucas (chums since we were 13) and the mysterious Fifi Chamoix.

‘Towers Open Fire’ was a collaboration between myself and ‘Brakeman’, an extraordinary composer and guitarist from Glastonbury. The songs are (with a couple of exceptions) my lyrics to his music, and the sound of the album is quite unique, with multi-tracked acoustic guitars in Brakeman’s highly unusual open tuning, and with only the addition of Cello and Percussion on some tracks. It’s quite unlike anything else I have ever done.

‘Music from The Garden of Fifi Chamoix’, is in fact a movie soundtrack album from a film I completed a few years ago, and released on DVD as ‘The Garden of Fifi Chamoix’, a surreal movie tracking the final year in the life of my girlfriend Fiona’s extraordinary garden before we both moved to the West Country. Recently I was reluctantly persuaded to look at my film music again, as a separate entity, but seeing it in a new light, I felt able to create, with some editing and re-mixing, what I think is a fascinating instrumental album, featuring the guitar of my old and valued collaborator, John Ellis (of The Vibrators, The Peter Gabriel Band and The Stranglers) and the Saxophones and Flutes of David Jackson, late of Van der Graaf Generator, together with the Cello of Helen Lunt.

You also wrote several stage musicals as lyricist with composer Maxwell Hutchinson. How did that come along?

This lengthy episode in my life came about because Maxwell and I wanted to write a long- form concept album. We wanted to do something very English, and having recently come out of Scientology, I was very interested in charismatic leaders and their followers, we were also both attracted to the period between the two World Wars. I eventually found the perfect subject in The Kindred of the Kibbo Kift, an anti-war breakaway movement from the Boy Scouts, founded in 1921 and led by the charismatic John Hargrave “White Fox”. I don’t have the space to go into this fascinating subject in any depth with you here, but it’s well worth researching. We had written most of this supposed concept album when we met, by chance, the theatre director Chris Parr. He was interested in hearing our songs, and then promptly suggested that we might like to turn it into a theatrical show for the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh. Max and I were both enthusiastic, the show was finished, and ‘The Kibbo Kift’ was produced in Edinburgh in 1976 and brought back for that year’s Edinburgh Festival, with another production at the Crucible the following year which was directed by Mel Smith, before he found fame as a comic actor.

I took the opportunity to recruit a band for the Crucible production who, while being paid for the show, could also rehearse my own songs, prior to me making another shot at leading a rock band. We called ourselves The Imperial Storm Band, and got as far as a residency at the Marquee Club and playing a few other gigs round London. I did quite a bit of dressing up on stage, and our show was pretty good, but the Punk revolution was carrying all in its path, and our quirky theatricality was not in favour at the time.

As a result of the modest success of ‘The Kibbo Kift’, the Traverse Theatre commissioned a second show from Max and myself. The first show was in the form of an unbroken succession of songs, but our second followed the more traditional format of acted scenes interspersed with songs. It was called ‘The Ascent of Wilberforce III’ and followed the disastrous progress of a 1927, League of Nations sponsored, expedition to the unclimbed Himalayan peak of Wilberforce III. The first twenty minutes of the show were in Esperanto; it featured a female disciple of Aleister Crowley and a singing Yeti. Nevertheless, the show was well liked and was very funny, with good songs. This production transferred to the Lyric Theatre, Hammersmith.

Max and I were also commissioned by the Michael Rudman, at that time the Artistic Director of the prestigious Hampstead Theatre Club, to write a musical for actor/musicians. We delivered ‘Geraldo’s Navy’ a musical about a dance band on a cruise ship. This was happily accepted by the Theatre, but was never produced.

Was it difficult to work on ‘The Book of Hours’?

‘The Book of Hours’ was one of the few projects of mine that I was not able to bring to a happy conclusion. Mel Smith, an established Theatre Director before he became famous as a comic actor, had directed a production of ‘The Kibbo Kift’ in 1977, and became interested in directing a new piece of mine at the Young Vic Theatre in London. I was writing a long- form piece for string quartet, vocals, bass and drums, with Michael Brand as its long- suffering string arranger, and Mel suggested that this could be performed as a semi-staged work for the theatre. The cast/musicians had to be drawn principally from the repertory company recruited by the Theatre for that season, so the string-players, with one exception were of no great ability. There was no drummer in the company, so I had to do it, which I didn’t enjoy, being a very dodgy drummer (and having to play very quietly as well) while an actor did the singing.

The subject was rather hackneyed, I have to confess; a-day-in-the-life of an unsuccessful songwriter, but it did have some good tunes and amusing lyrics.

Shortly afterwards, I was offered a couple of days’ free recording in the Marquee Studios (behind the famous club in Wardour Street). Michael hired a half-way decent string quartet, my old friend from The Imperial Storm Band, Ian Fordham played bass-guitar, and, wonder of wonders, the session drummer that Michael had booked was none other than the legendary Clem Cattini who, to date, has played on 43 Number One UK hit singles.

There was nowhere near enough time to get such a long, complex piece into very good shape in the time we had, and, because the studio time was free, we were given the services of a junior, inexperienced engineer, who had never recorded strings before. Mel Smith came by and very kindly performed, hilariously, as an offensive record executive, while a three-girl brass and vocal group called Soul Yard provided some great backing vocals.

However, we came out of it with a reasonable demo, but nothing more than that, so my answer would have to be “Yes, it was difficult to work on ‘The Book Of Hours’”.

You also collaborated with Lene Lovich.

I first met Lene in, I think, in 1971. She and her partner Les, and I, had rooms above a Greek fish-and-chips shop just off the Tottenham Court Road, right by Goodge Street Station. Our rent was £4.50 a week, which then went up to £5.00 and we were outraged. Les and Lene were art students at the Central School of Art, while I worked at the Scientology centre nearby. They have been my friends ever since. Lene is an extraordinary person, and I have a great respect for her as an artist. She has written many very fine songs. She came to music performance gradually, I think. At one point early on, she recorded some backing vocals for me in a soft, wispy tone, but I could hear that there was a huge, loud, dramatic voice in there waiting to come out. Then Lene and Les got their break, and, quite rapidly, she became a very big star following her second solo single ‘Lucky Number’ in 1978. I wrote several songs for her later on, and she recorded a few, with some success.

I went on to co-write another musical ‘Mata Hari’ with, and starring Lene Lovich, about the famous spy, produced at the Lyric, Hammersmith in 1982, which broke box-office records but was not liked by the critics. I think Lene came up with the subject, ‘Mata Hari – the famous spy’, and I wrote most of the narrative and musical linking sections of the musical, while Lene came up with her own numbers. It was potentially a very good show, but the idea was that Lene (a pop-singer, not an actress) would be supported by three male actor/singer/dancers who would “carry her through” the performance. In the event, it turned out that they couldn’t sing, or dance, or even act very well, and, and she ended up carrying them through the show! Lene is a trooper. She coped wonderfully, and the theatre was sold out, even though the reviews were, justifiably, not enthusiastic. The episode soured me on doing musical theatre for life, and I’ve never touched it since. Without the resources of the West End or Broadway, it’s just so difficult to do a musical theatre show properly. It’s not a budget art-form.

Since then Lene has sung on several of my albums, and though she is no longer a young woman, her voice still sounds seventeen, and cute. Lene is definitely a bit special.

Around 1973 you collaborated with Peter Hammill again. You began working on an opera based on the short story ‘The Fall of the House of Usher’ by Edgar Allan Poe. That must have been a massive project.

Oh yes! “Massive” is about it. As you say, Peter started working on the music in 1973, to a libretto that I had sent to him the previous year. I’d been fascinated with the idea of a musical rendering of the Poe story since I had been at school, and Peter liked the idea of working on a long-term music-theatre piece.

The way the writing proceeded was very interesting, and I would consider it an ideal sort of process, if time is not a consideration. Peter would compose music for a piece of the text, which generally would follow my lyrics for a bit and then sail off into wonderful, uncharted waters. He would send this demo to me on cassette and I would amend, or rewrite, or extend the text to fit his music, and send it back to him. As the process continued, further re-writes, edits and extensions would be made as the work slowly took form. This went on for the next eighteen years! Most years we were able to spend a week or two on the project, although there was a space of four years or so, when Van der Graaf were particularly busy, when no progress was made.

Then there was a tantalising episode around 1990, when it seemed very likely that we would have the opera staged in Barcelona as one of the art events surrounding the 1992 Olympic Games. It got very close but foundered at the last fence, a victim, apparently, of city, versus national, versus Olympic politics. I think this galvanised Peter into completing ‘Usher’ and preparing it for a CD release. Lene Lovich sang Madeline Usher, and made an excellent job of it. The Narrator, at Peter’s suggestion, became a female role, sung by Sara- Jane Morris, while The Herbalist was performed by German rock-star, Herbert Gronemeyer (a part which I confess I would have liked to have sung myself.) Peter, of course was Usher, while his friend, Montressor, the unwitting witness to all these horrific Gothic goings-on, was sung by Andy Bell of Erasure. The vocal parts were demanding, but the performances were uniformly excellent.

‘Usher’ is a pretty remarkable thing. Peter’s music, despite being written over such a long period, is all of a piece, and remains consistent in style. I may be prejudiced, but I still think the music is absolutely stunning. It was first released in 1992, but at the end of the ‘90s, in an unusual move, Peter returned to the project and re-recorded much of the music together with his own vocals and released this second version of the work, fuller in sound and more elaborately recorded, just in time for the millennium.

What’s the concept behind ‘The Universe is Made of Voices’, a book exploring the idea of “Life After Death”.

I was always interested in, what I call “spooky stuff”; psychic phenomena, the Afterlife and so on. I read quite a lot on the subject while I was quite young, including Conan Doyle’s

Spiritualist novel ‘The Land of Mist’ which I found fascinating and well up with his best writing, despite attracting violently negative criticism. Around 1994, I had the good fortune to meet some very interesting and well-informed people who were active in researching spiritualistic phenomena, and for several years I was able to participate in numerous experimental séances with different mediums. As a result of my experiences, I became, and remain, quite convinced, that the evidence for Life After Death is overwhelming.

However my book, which went through various partial publications and earlier versions, is not a collection of my strange experiences, but is supposed to be a handbook or manual to enable interested people to do their own research and reach their own conclusions on the subject, and, most importantly, to be able to do this in a safe and controlled way. There are very few subjects that are so hung about with nonsense and superstition, and I have attempted to cut through the disinformation for the benefit of those people who might be engaged by the question of whether physical death is actually the end of our individual existence. Many people will not be remotely interested in this subject, and I have no wish to change their minds. However for those who are interested, I think I may have some good and useful information for them.

What currently occupies your life? Any other future projects we should expect?

I am always busy with something, and I am currently more than half-way through a new solo album, which I am hoping to release in time for Christmas. It is called ‘Old Man In A Hurry’ and is an album of new songs. There are still other projects I would like to do if I am spared, and I doubt that I will retire until I drop.

Did I miss something?

Your questions have been good, and I have not done such a comprehensive interview for a long time, but obviously there is so much stuff that we haven’t been able to touch on. Maybe I should do another book. There are lots of grizzled old musos bashing out their memoirs, but perhaps I’m better employed in making more music.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

All I would say is, “Please check my stuff out”. All my physical albums and the book are available from my website. I send items out promptly to customers all round the world, and the website has a massive amount of material about all my various projects. Alternatively, you can go to Bandcamp to buy high-definition digital downloads or digital streaming of my music, with ample opportunities to “hear before you buy”.

Thank you, Klemen, and all at It’s Psychedelic Baby! Magazine for this opportunity to sound- off at such length.

Klemen Breznikar

Judge Smith Official Website / Facebook / Bandcamp

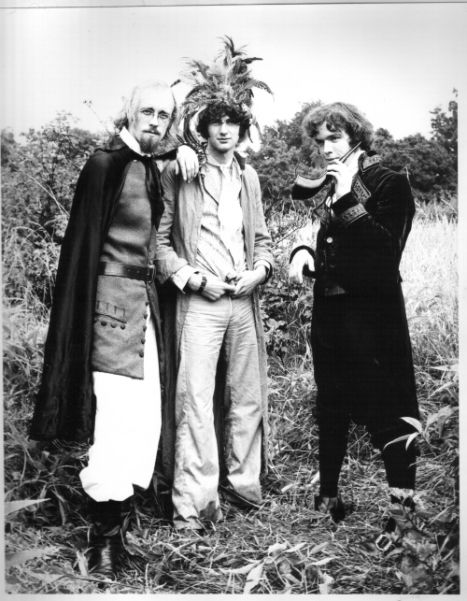

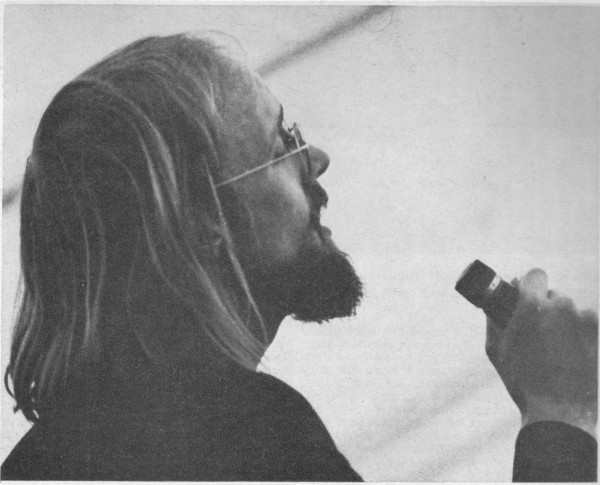

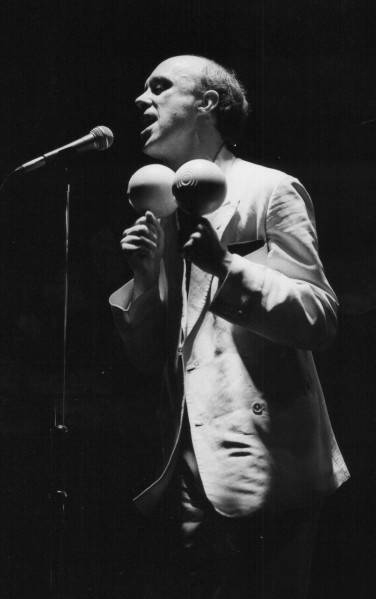

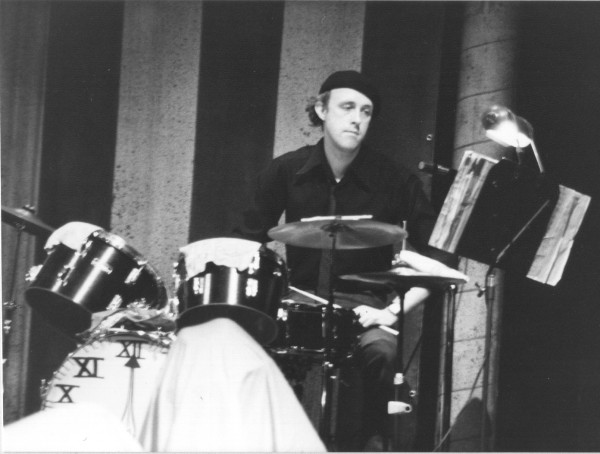

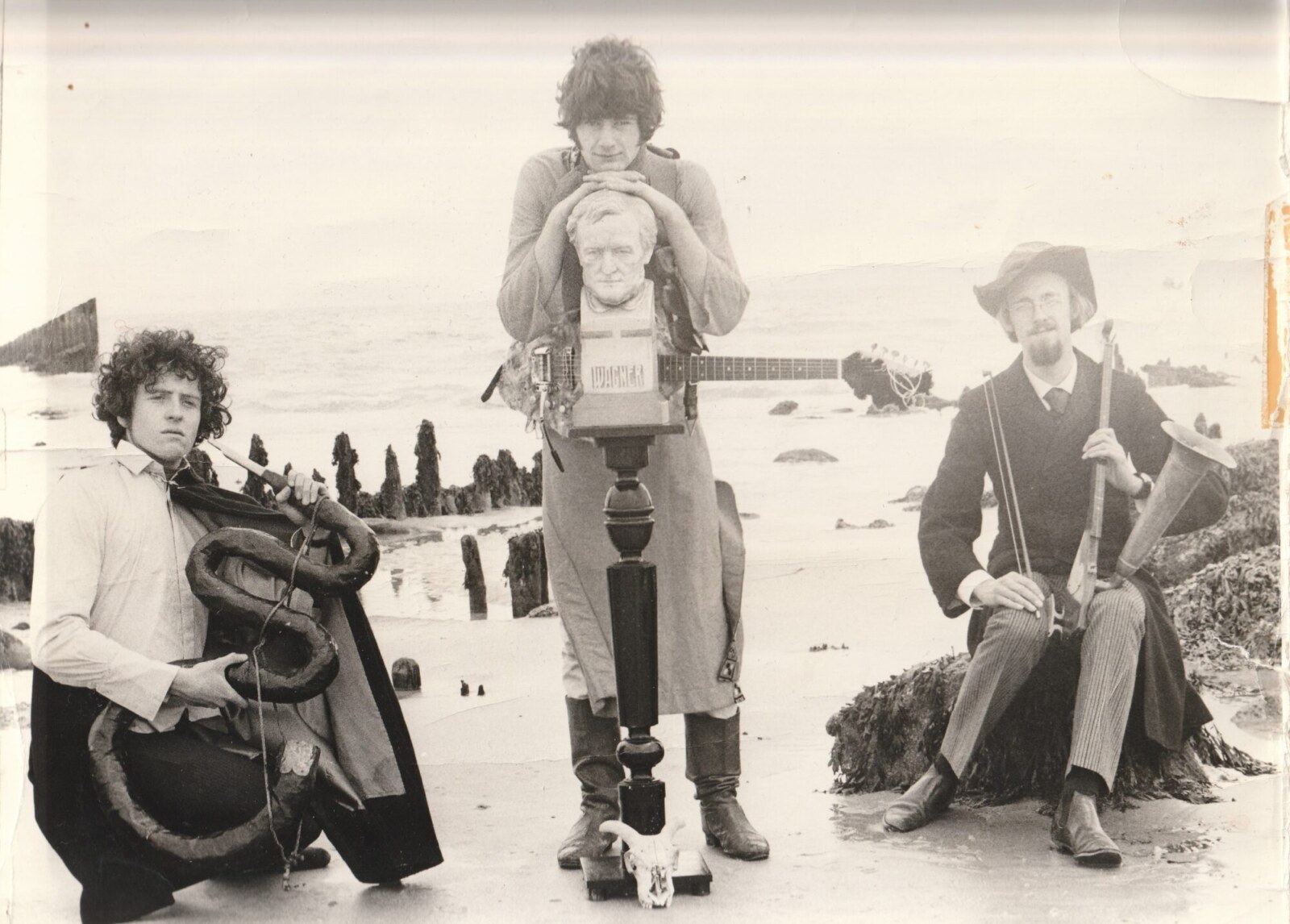

Headline photo: Van der Graaf Generator in 1968 | Photo by Gordian Troeller

Klemen, thanks for the interesting interview.

It’s just a shame that you didn’t ask about his stay in S. F. 1967. For example which bands he saw live and which oness he particularly like.

I was in California in the early 70’s. But in 1967 that was of course much more interesting. Again a shame about the omission.

Many thanks for publishing that interview – a great read – about a very talented chap!

Until the very recent covers album – I don’t think Peter Hammill ever played ANYONE else’s tunes but his own – but with the notable exception being Judge Smith songs that he’s returned to many times over the years – the stunning Four Pails, Been Alone So Long and Time for a Change spring to mind.

I can’t recommend Judge’s stuff more highly – Orfeas in particular is an absolute hoot – an enormously entertaining songstory – that dazzles you with a combination of musical genres, a strong narrative, brilliant performances from the guest musicians, and it is also very funny!