Nick Haeffner | Interview | ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’

‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’ is a recently released compilation of instrumental tracks recorded between 2017 and 2022 which acts as an introduction to Nick Haeffner’s musical universe.

Nick’s first exposure was as a member of cult indie band Clive Pig and the Hopeful Chinamen. Subsequently he joined The Tea Set, with whom he recorded two singles and an album before releasing a highly acclaimed solo album ‘The Great Indoors’ in 1986 (Bam Caruso).

Several of the tracks on ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’ have the epic sweep of film soundtracks while others are more intimate, acoustic guitar based pieces. There is a smorgasbord of instrumentation including fuzz guitar, accordion, French horn, Chinese Erhu violin, Turkish oud, ukulele, orchestral strings, Ukrainian and Norwegian violins, mandolin, Hammond organ, electric piano, sitar, harp, synthesiser and piano. Some of these are sampled, many are played live. The music is melodic, quirky, surprising and inventive. The album has guest appearances by Andy Golding (The Wolfhounds, Dragon Welding), Finn Kidd (Tim Burgess, Hatcham Social), Mike Adcock (Clive Bell, Chris Cundy, Imaginary Dance Trio), Sylvia Hallett (Evan Parker, David Toop, Clive Bell, Lol Coxhill) and Ian Montague (Julie Felix, Linda Moylan).

It’s really nice to have you. ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’ was recently released so it’s really great to discuss it with you. The album consists of instrumental tracks recorded between 2017 and 2022. Was there a certain concept you had in mind?

Nick Haeffner: ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’ is a mini-album sampler which retails at a budget price of £3, so for the price of a cup of coffee you get an introduction to my music. The 30 minute set provides a taster of my music using previously unreleased recordings (although some of the tracks are re-recorded versions of previously released compositions). My albums are a mix of instrumental and vocal tracks but in this case I decided to focus on the instrumental side of my music as it’s what makes my music particularly distinctive. It’s also where the music is at its most adventurous and experimental.

Where was the album recorded and how much time did you spend on it? Who was the producer?

I recorded all the tracks at home and produced them myself, playing most of the instruments. Again, this gives a strong sense of my personal approach to making music. I was something of a frustrated producer when I first started out, lacking the technical knowledge to get the sounds I heard in my head. Now I find I’m more confident and really enjoy the production side of things.

The album consists of tracks that can sound epic in moments, but at the same time there are also very intimate acoustic pieces. How did you decide how to balance the album?

Contrast and variety are very important to me. I think that contrast is the basis of our interest in any artform. Pure consistency very quickly gets “samey” and boring. I grew up listening to a very wide range of music. Among the most affordable albums when I was younger were “sampler” albums put out by record labels. I found that after listening to one of these albums a few times that I liked nearly all the bands and styles of music. It’s always felt natural to me that an album should contain more than one style of music. The Beatles also based their albums on the principle of variety. The idea of variety in popular culture has a long history. People used to go to a music hall (or Vaudeville in the US) for an evening of mixed entertainment, featuring a wide range of performers and genres. These were often called variety shows. I think the Beatles actually took that tradition and modernised it for the psychedelic mindset, which is (or should be), exceptionally “open” to everything.

You were experimenting with a lot of different instruments, would you like to talk about the experimentation you did…

I have always enjoyed using a wide range of instruments. On my first album, ‘The Great Indoors,’ I used the sounds of a tuba, a trumpet, a double bass, vibes, accordion, slide guitar, string quartet and many others. This is partly connected with the above considerations but also perhaps because the singer songwriters I heard in my early teens had arrangers who would bring in different instruments to give mood and colour to the songs. The first album I owned was ‘Candles in the Rain’ by Melanie which featured double bass, a string section, accordion, organ, flute and a gospel choir. The music of the 60s and 70s that I grew up with often featured a range of orchestral instruments in addition to guitar, bass and drums. Think of all the instruments used by the Beatles on just two of their classic albums, ‘Rubber Soul’ and ‘Revolver’: the string octet on ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ the sitar on ‘Norwegian Wood,’ the French Horn on ‘For No One,’ ocarina and tape loops on ‘Yellow Submarine,’ trumpet and sax on ‘Got to Get You Into My Life,’ tabla on ‘Love You To’ – that’s just a few examples. It’s always been my ambition to make music with such a colourful palette and that’s what I do on ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’.

Of course, hiring lots of trained musicians has been out of the reach for most artists on small record labels but I was fortunate that Phil Smee of Bam Caruso paid for some session musicians for my first album and where the budget wouldn’t stretch, other instruments were added using a sampler with a keyboard, which had only just come on the market when I made that first record.

Now I have access to a vast range of sampled instruments from the library in Logic that I can play through a keyboard. I also use loops which contain very short passages of music that are pre-recorded by an orchestra, a string quartet, a wind instrument or a cello. In addition to these instruments, I can turn my hand to most keyboards, some percussion and most stringed fretted instruments. Among the stringed instruments I often use are the ukulele, banjo, nylon string guitar, 12 string guitar, mandolin and bouzouki.

The album has guest appearances that include Andy Golding (The Wolfhounds, Dragon Welding), Finn Kidd (Tim Burgess, Hatcham Social), Mike Adcock (Clive Bell, Chris Cundy, Imaginary Dance Trio), Sylvia Hallett (Evan Parker, David Toop, Clive Bell, Lol Coxhill) and Ian Montague (Julie Felix, Linda Moylan). Would you like to talk about the collaboration?

I invited my Dimple Discs label-mate Andy Golding to contribute to ‘Slouching Towards Walthamstow’ as I had a hunch he’d come up with something I wouldn’t have thought of. I was right. Andy got hold of an out of tune toy guitar and just played along with the track. I dropped his playing in and out of the track, I think it adds a totally new dimension to it.

Originally ‘Everything Begins Again,’ a track which was originally released with vocals on ‘A New Life Awaits You,’ I used a very repetitive drum machine. Brian O’Shaunessey, who helped me to mix the track put me in touch with Finn Kidd who replaced the drum machine with a much better drum track.

‘Ludwig at Clearwater’ was originally recorded for an album by accordionist Mike Adcock. Mike sent an improvised piece of accordion playing to me, Sylvia Hallett and his son, Simon Adcock. Each of us improvised over the accordion playing and the track was released by Mike on an album of improvised music called ‘The Ludwig Variations’. As an experiment, Mike took out his accordion part for a remixed version. I really liked the way that instruments appeared to float in thin air without the accordion backing. Mike gave me permission to release the new version on ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’.

Ian Montague is a local musician with whom I’ve worked quite a lot lately. He plays bass on ‘Slouching Towards Walthamstow’ because he’s better at it than I am.

How would you compare it to your previous album, ‘A New Life Awaits You’?

‘A New Life Awaits You’ is very different. ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’ is a mini compilation album with purely instrumental tracks drawn from different time periods and projects. ‘A New Life Awaits You’ is a mixture of songs and instrumentals. It was conceived as a concept album where all the tracks contribute to a sci-fi backstory about a disembodied consciousness that has survived the end of the world (brought about by a combination of nuclear war, pandemic and environmental catastrophe). This consciousness now only exists virtually and only has memories for experiences. Each of the tracks represents a memory.

‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’ has some material from that recording session. There is an earlier version of ‘Goodbye Mr Pushkin,’ which is featured on ‘A New Life’ and two tracks which I recorded for that album but didn’t use, ‘Grand Hotel Abyss’ and ‘A New Life Awaits You,’ which would have been the title track for the previous album but I felt it was too downbeat.

Would you like to talk about the early beginnings? What was the scene in your town, what kind of gigs did you see as a teenager and what kind of records did you own?

My parents moved around a lot in my childhood but my teens and early twenties were spent in St Albans, a small city just outside London which has the highest density of pubs in Britain, I believe. I spent a lot of my youth in those pubs and there were a number of places to play live, even if you were unknown.

I started playing the guitar around 1975/76 so pub rock was really big. There was a pub called The Horn of Plenty with a back room for bands to play. It was always packed to the rafters and there were some really good local bands. I first met Brian Marshall, who produced ‘The Great Indoors,’ when he was a regular at The Horn.

Were you in any bands before The Tea Set?

Yes, I was in Clive Pig and the Hopeful Chinamen.

Tell us about your involvement with Clive Pig and the Hopeful Chinamen?

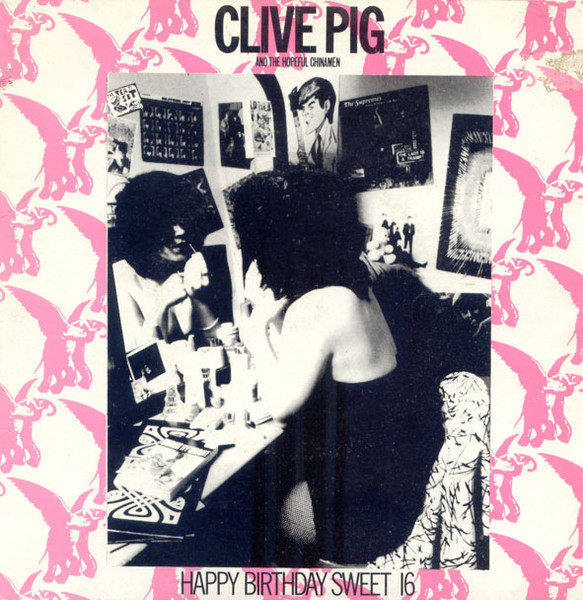

Before joining The Tea Set, I used to go to a folk club in St Albans at a pub called The Goat (I think Donovan used to play there). One evening, a guy called Clive Piggott got up and performed a set. Clive was really something else. His main influence was Jacques Brel and he had the same raw intensity and vocal power. Clive had one song, ‘Happy Birthday Sweet 16,’ that sounded like a surefire hit single, everyone told him so.

I’d been experimenting with two cassette recorders at home, working out how to multitrack myself by bouncing back and forth between the two machines. I approached Clive and offered to help him record a demo for ‘Happy Birthday Sweet 16,’ with the aim of getting it released by a new local label, Waldo Records, run by sleeve designer Phil Smee. On the final demo, I played lead guitar and a guy called Gary Hawkins played drums. We subsequently formed a band to play live called Clive Pig and the Hopeful Chinamen (you’ll have to ask Clive about that name).

In 1979, Phil released ‘Happy Birthday Sweet 16’ by Clive Pig and the Hopeful Chinamen as a 7” single in a triple gatefold sleeve. Once again, everyone who heard it thought it would be a big hit single. It wasn’t to be, however. The edgy and clever lyrics contained the words “cystitis” and “black bra,” which earned the single an outright ban on Radio One, the only station that mattered at the time. It has since become a cult indie classic.

Would you like to elaborate on the formation of The Tea Set?

Clive Pig and the Hopeful Chinamen played a few gigs and recorded a promising demo with the backing of Phil Smee who had released an EP called ‘Cups and Saucers’ by a local art school band called The Tea Set. The Tea Set evolved out of a band that included Bruce Gilbert (who went on to form Wire with other students from Watford Art College). With the departure of Duncan Stringer, The Tea Set were looking for a new guitarist. On the basis of my guitar playing with Clive (which they considered “psychedelic”), they invited me to join. I was still only 20 years old and the rest of the band were older so it was very exciting for me to be involved in something that was attracting a lot of positive attention. I was also very nervous, shy and a closeted gay man so I didn’t always find it easy to fit in but being in the band brought great opportunities and experiences.

The band released an EP and several fantastic singles, looking back now, what are some of the highlights in your opinion?

The first thing I did after joining The Tea Set was a John Peel session for BBC Radio 1. We recorded four songs in the BBC studio with a producer called Bob Sargeant. The session went really well, we were very happy with the recording which caught a lot of energy and excitement. John Peel really liked it, he played it twice but perhaps more importantly, the session was heard by Hugh Cornwell of The Stranglers who said that he wanted to produce the band.

Unfortunately, the recording session didn’t go very smoothly. Cornwell was not an experienced producer and we ran out of time and money working on the B side which meant that there was no money to record the A side. A decision was taken to release the B side (‘Keep on Running’) as the main track which didn’t work very well. However, we did get to tour the UK with The Stranglers which was very exciting.

We also toured with The Skids, another post punk band that was very successful at the time. After touring, we were given the opportunity to record for a week at a small but very well equipped studio in Hastings, which I believe was owned by Paul McCartney. We were given a producer, Steve James, and the idea was to see if we could record a whole album in a week. Unfortunately the album was never finished, even though it is probably the finest thing that the band did. The band broke up not long after that.

Nick Egan, the singer of The Tea Set, found success designing record covers for the likes of Bob Dylan and Iggy Pop. He also directed music videos for INXS, Sonic Youth, Duran Duran and Mick Jagger. Cally, the band’s drummer, went on to manage Julian Cope and the estate of Nick Drake.

“My albums are like icebergs”

I think your 1987 solo album is an overlooked psych pop masterpiece, would you like to share some further words about it? What are some of the strongest memories from recording it?

Thank you! Quite a few record collectors regard the album very highly but it remains very little known, in spite of a reissue in 2019 as a two CD box set by Hanky Panky Records. I have a lot of affection for the album and it turned out better than I could have hoped. There’s a lot to take in so I think it’s necessary to listen to the music quite a lot to get the most out of it. My albums are like icebergs, nine tenths of them are below the surface. The people who think highly of ‘The Great Indoors’ are people who haven’t stopped playing it since it came out. I don’t think one listen will reveal all that much, even though the music isn’t at all difficult to listen to. The same applies to my previous album, ‘A New Life Awaits You,’ I think people are only just getting to know it but those people are now finding some magic in it.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

Ok, here goes:

I often go back to pioneers like Charlie Christian, Sister Rosetta Tharp, Scotty Moore, Link Wray, Mick Green (The Pirates) and Hank Marvin. They are all great stylists who know when to keep it simple, something I keep reminding myself to do.

I like playing that is fiery but controlled, for instance: Robert Fripp (particularly ‘The Sailor’s Tale’), Ernie Isley, Randy California, Wilco Johnson, Prince, John Perry.

Many of my favourite guitarists are very steeped in tradition. They draw on roots music but do something very elegant with it: George Harrison, Steve Cropper, Richard Thompson, Ry Cooder, David Lindley, Marc Ribot and Bill Frisell are some of my favourites.

Acoustic guitarists: John Fahey, Joni Mitchell, John Martyn, Nick Drake. I’m not so keen on very delicate, whispy playing. I like players who get quite a full, earthy sound. The first time I heard the acoustic guitar on ‘Magic Bus’ by The Who was a revelation for me.

I’m also influenced by many songwriters including John Cale, Kevin Ayers, Nico, Judy Collins, Todd Rundgren, Joao Gilberto, Harry Nilsson, Jon Brion, Eno and Sean O’Hagan. I particularly like their feel for chord changes and arrangements.

Then again, I also like instrumental compositions and abstract soundscapes. Probably my favourite soundtrack composer is Ennio Morricone but I also like Michel Legrand, Basil Kircher, Angelo Badelamenti and Mica Levi (for ‘Under the Skin’). I’ve always liked abstract sounds. I was given a record of electronic music when I was very young which contained compositions by Ilhan Mimaroglu (Agony), Luciano Berio and John Cage. Later I discovered Wendy Carlos, Can, Holger Czukay’s ‘Movies,’ Delia Derbyshire, Laurie Spiegel, William Basinski, Arthur Russell, Pauline Oliveros, Jon Hassell, Gazelle Twin and Alison Cotton.

How did you get involved with U2, Iggy Pop, The Clash and XTC?

I think this was due to the manager of The Tea Set and Nick Egan, our singer who both worked hard to get us support slots. Nick Egan was friendly with The Clash, Nick Simenon in particular and our manager (Art Bennett) was friendly with the management company of The Stranglers, which also helped to secure good support slots.

When did you get involved in university? Tell us about your lectures…

After the initial interest in ‘The Great Indoors’ died down I had a lot of trouble coming up with a follow up album. Bam Caruso had been sold and no other record company seemed interested in financing another album. I found it difficult to write and lost focus artistically. I also needed to get a job to earn some money. I signed on for a degree course at what is now the University of East London, while working at the legendary Scala Cinema in Kings Cross and doing a bit of work as a DJ. After graduating from the course, I took an MA and a PhD at Sussex University.

I taught film studies for a while at Westminster University and the British Film Institute before taking a full time job at the Cass School of Art where I taught film, art and photography. I also managed a team of lecturers. My main area of interest was cultural history. While I was teaching I published a book about the films of Alfred Hitchcock and another book about photography of the East End of London (with Susan Andrews). I also published some journal articles about film and photography. The main problem was that the job took up so much of my time that I gave up music completely for over 30 years.

In 2017, I made the decision to quit my full time job and work on my photography. However, the university gave me a long service award which I spent on a very nice acoustic guitar and it wasn’t long before I was experimenting with multi-tracking again, this time on my laptop, firstly with GarageBand and subsequently with Logic. With more time to spare and a bit of help from my old friend Richard Norris, I started to build up a collection of recordings using Logic and at a certain point decided that they might be good enough to release as an album.

I mixed the tracks at a local studio and released the album on my own label as ‘A New Life Awaits You, vol. 1’. The album did not sell very well but I had some great feedback from people who knew ‘The Great Indoors,’ most notably from Alan Moore who was already a fan of the first album. Alan wrote me a long letter saying how much he liked ‘A New Life Awaits You’.

Through Facebook I then made contact with Brian O’Neill, another fan of ‘The Great Indoors’ who was very enthusiastic about ‘A New Life’. Brian was in the process of starting a record label called Dimple Discs with Damian O’Neill of The Undertones. Brian offered to release my next project, a re-interpretation of ‘The Point by Harry Nilsson,’ one of my earliest influences. Brian also helped me to get singers and musicians on the label to appear on the album. I’m very proud of the result which Dimple Discs will release early in 2023. In the meantime, Brian suggested I put out a collection of my instrumentals to create interest, so that’s how ‘The Electromagnetic Imaginary’ came into being. Dimple Discs will also release my next solo album which I hope will come out before the end of this year.

Are you planning to play some gigs?

I have just started playing live again in London and so far it’s going really well. I would like to get some gigs outside London, so if anyone reading this would like to offer me a gig, get in touch!

What else currently occupies your life?

Cats. Photography. Nicolai.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

Save the planet!

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Rocco Venna

Nick Haeffner Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

Dimple Discs Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube