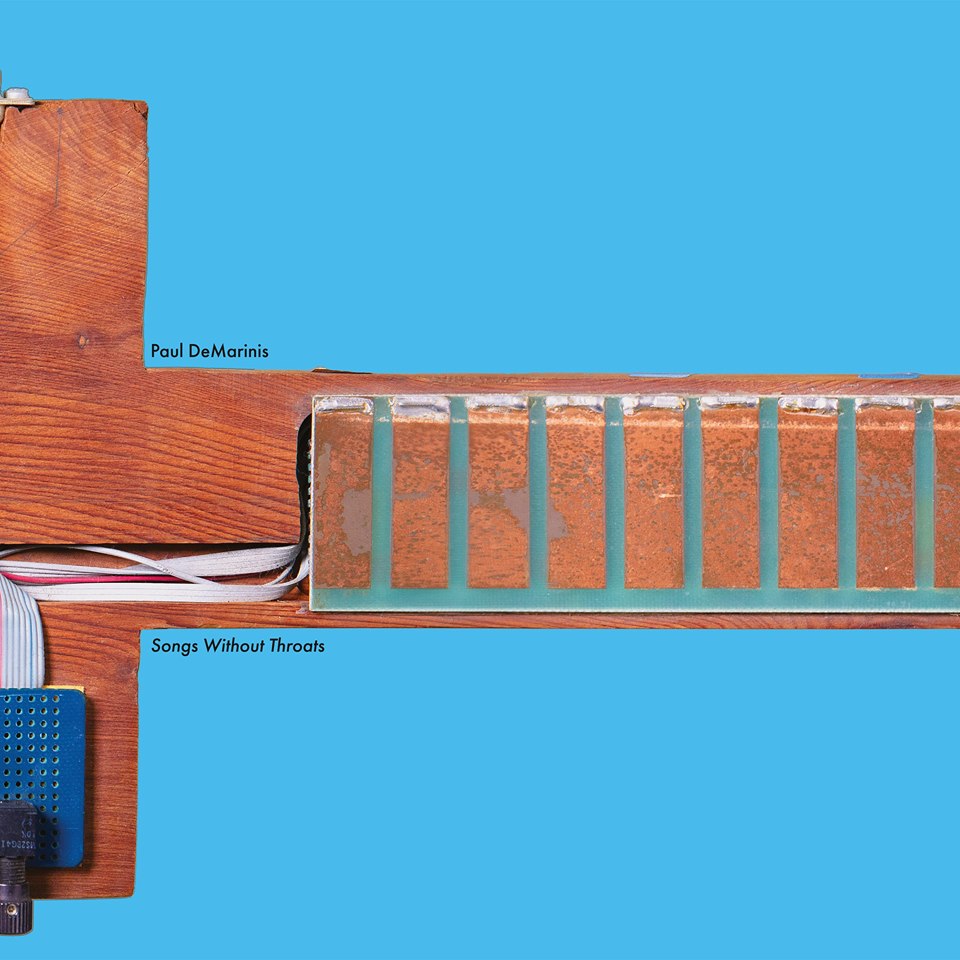

Paul DeMarinis

Together with Oren Ambarchi, American visual and sound artist Paul DeMarinis compiled 13 recordings from the late 70s until 1995 for the double LP ‘Songs Without Throats’, out on Ambarchi’s own Black Truffle label.

Why did it took you two years to put this compilation together?

Well, not really 2 years. Oren suggested we do something from my old work back in fall of 2017. It took me a while to dig stuff out from old reel-to-reel tapes, cassettes, DATs etc; then it took a while to sequence them in a plausible way, touch up the sound (few of the tracks were intended for publication in the first place) and then a while to master and also there were other projects of Oren’s ahead in the queue. So about 16 months.

Why compilation and not new material?

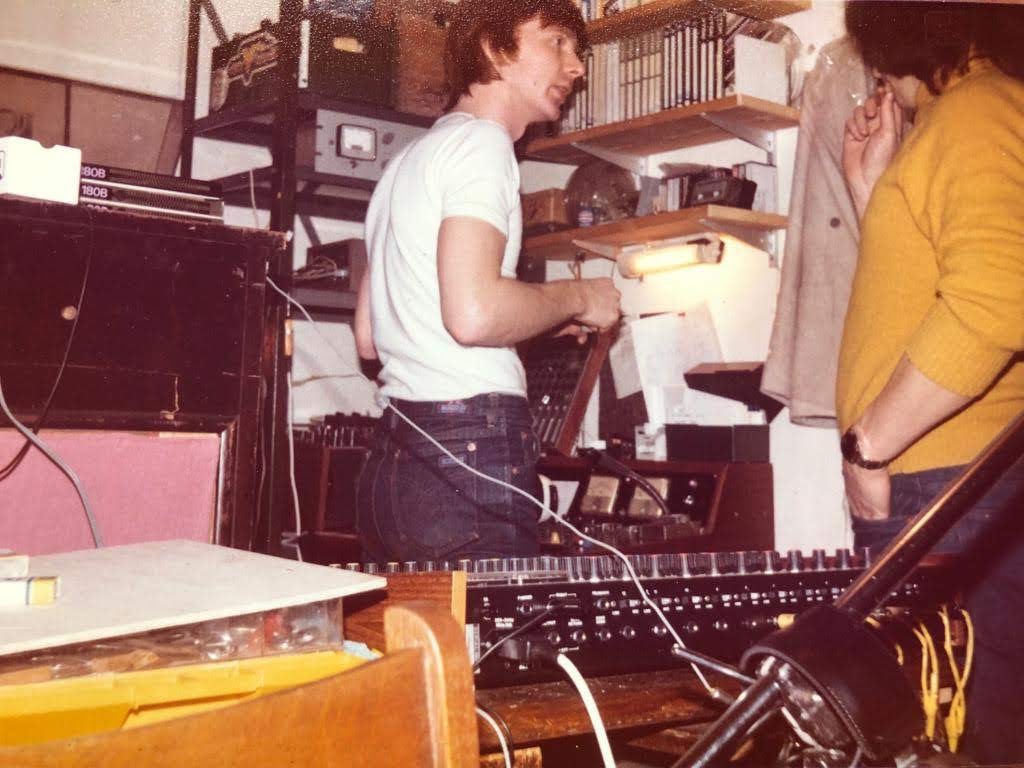

Most of my work in the last 20 years (and much of it before that) has been installation and objects for exhibitions in museums and art galleries. I don’t perform much, or make recordable audio pieces. The only material I had for an LP release was this old stuff, indeed from the days when LPs were the only form of music distribution. Some had appeared on various artist compilations in old formats.

Why did you select works from this period (late 70s – 1995)?

The long period from which these works are collected belies period as a common factor, What ties these works together is that all these pieces use synthetic speech or in the case of “…Comrade Stalin…”, heavily digitally processed speech sounds.

Why is this compilation called ‘Songs Without Throats’?

Because of the synthetic speech.

Why did you decide to built your own electronic instruments (instead of using already existing instruments)?

In most cases the equipment to do what I needed didn’t exist at the time. I had to design electronics, or hack existing sound modules or code DSP algorithms myself to get the things I wanted to hear.

Why did you use Stalin’s voice? Does this have a political context, for you? Or is it just about the voice, without its meaning?

“The Lecture of Comrade Stalin at the Extraordinary 8th Plenary Congress about the Draft Concept of the Constitution of the Soviet Union on November 25, 1936” (c) 1998 Paul DeMarinis.

During a visit to Tallinn in 1995 I found a set of twenty 10-inch 78 rpm records of a speech by Joseph Stalin in a junk store. Together with Paul Panhuysen, the set was purchased and divided between us with the agreement that we would provide each other with DAT tapes of the disks in our possession. In addition we agreed that we would create independent works based on the material and at some point in the future, make an exhibition or project together of our resulting works. I have created a number of pieces from the material including visual objects, kinetic sculptures and sound compositions. All these works carry the identical title, “The Lecture of Comrade Stalin at the Extraordinary 8th Plenary Congress about the Draft Concept of the Constitution of the Soviet Union on November 25, 1936” so there is some confusion about the exact identity, as well as the medium of, my work – perhaps my own paranoid response to a potentially monstrous presence lurking in these grooves.

Stalin was rarely recorded and even less frequently were his recorded words, even his greatest wartime speeches, released as audio documents. While myriad printed volumes of his writings survive, translated into more languages than even The Watchtower, Stalin’s voice seems to be hiding somewhere behind rather than within the bright-red bound volumes. With good reason, conjecture historians: his thick Georgian drawl, the kind of thing that would be an outright asset to an American politician, made him feel like a foreigner in the Kremlin1. As a tyrannosaurus among dictators, flourishing in the age of the great dictators – great vocal personalities, like Hitler, Mussolini, Churchill & Roosevelt who performed like brilliant stars on stage, on radio, and in film – Stalin is something of a vocal mystery-man. No one seems to remember the grain of his voice. When we listen to the arid forty2 sides of his 1936 release the reason becomes apparent: Stalin’s voice is quiet and mumbling. Short utterances are like uninhabited islands somehow lost in a sea of embarrassing pauses, now filled in by the oceanic roar of cheap Soviet bakelite.

The occasion of this speech was of particular significance, given on the eve of the ratification of the Soviet Constitution – in his day referred to lovingly as the “Stalin Constitution.” The speech of November 25, 1936, amid the show trials and purges, represented something of an imperial coronation standing, as it does, midway between Kirov’s assassination and Bukharin’s last plea. Within this speech Stalin declared that the Soviet Union had now passed from the state of socialism into communism. If this news reached Highgate Cemetery in London, it is certain that much in-grave rotation resulted. This hardly Marxian pronouncement was, in effect, a call to total agrarian collectivization and a rationalization for the wholesale liquidation of the kulak class and persecution of the intelligensia. This speech was broadcast throughout the Soviet Union and heard by everyone. It announced Stalin’s brutal hegemony after years of bloody purges, his triumph as the defining force of Soviet communism. The full recording was released as a boxed set so that frequent re-broadcast and listening could indoctrinate the masses in the new cult of personality that was to endure until Stalin’s death in 1953.

The Lecture of Comrade Stalin at the Extraordinary 8th Plenary Congress about the Draft Concept of the Constitution of the Soviet Union on November 25, 1936 uses a variety of sound materials alongside and in combination with Stalin’s own voice. Other voices from the spirit realm herald the openings and closing of doors in the various sections of the work. Birds and birdlike whistles, deriving both from the Kaluli spirit world and from formant-glides extracted from Stalin’s own voice, serve to convey his presence at a safer, more abstracted distance. Musical ghosts also abound both in the form of thematic quotations and as “morphed” samples. These are combined with and replicated within Stalin’s voice by a variety of digital analysis/resynthesis techniques. In most cases karmically if not historically wed to Stalin’s voice, they derive from musical sources associated with the dictator.

If Stalin’s voice, like Lina Lamont’s, was a weak point in his stardom, voice was also central to Stalin’s inner identity. As a young seminarian in the Orthodox church, Joseph Djugashvili was known for his fine singing voice. On the closer listening that computer analysis affords, melodic movements are heard within the short mumbled phrases that are perhaps ghosts of the Georgian liturgical music he once sang. Echoes of the earnest young seminarian, singing with avowed devotion, are heard in the earlier parts of the work.

Stalin’s renown as a music critic stems from his review, in Pravda under an assumed name, of Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera, Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District in 1936. The opera’s plot concerns a murder spree by a bored bourgeois housewife, Ekaterina, and her lover Sergei. Anecdote has it that Stalin’s abrupt departure from the opera mid-performance was due to his moral indignation at certain “erotic” trombone glissandi that accompany Sergei’s penile detumescence. Other readings of this decisive departure are possible, though. The victims of the lover’s crimes are small landowners and the blood on Ekaterina’s hands smells a lot like that on Stalin’s after the mass exterminations in the Ukraine in 1932. The Pravda article nearly cost Shostakovich his life, and made him especially vulnerable to official criticism for the rest of his career. Strains from his musical penance, the 5th Symphony, composed immediately after his fall from grace, also find their way into these grooves. Elvis too, the inheritor of the WWII dictatorial-oratory-become ballad, involves himself insidiously throughout the work. As a Hollywood version of Sergei, he mingles climactically with Ekaterina’s ecstasies and stands in as Stalin’s radiophonic double.

Of course we might wonder about Stalin’s private tastes in music. An intriguing mention is made by Yugoslav envoy Milovan Djilas in Conversations with Stalin. He describes a very tense late night meeting that took place at Stalin’s dacha on the eve of Tito’s split with the USSR early in 1948.

“…before we began to disperse, Stalin turned on a huge automatic record player. He even tried to dance, in the style of his homeland. One could see that he was not without a sense of rhythm…

Then Stalin turned on a record on which the coloratura warbling of a singer was accompanied by the yowling and barking of dogs. He laughed with an exaggerated, immoderate mirth, but on detecting incomprehension and displeasure on my face, he explained, almost as though to excuse himself, “Well, still it’s clever, devilishly clever.”3

An automatic record player? This was perhaps the large RCA console given to Stalin by Harry Truman, but the record described would seem totally contrary to the ruling Soviet musical tastes. Indeed, could such a record have been produced and disseminated in the late 1940’s in the USSR? Perhaps, like the phonograph, it was an import. And the import that leaps to mind on reading Djilas’ description would be “Il Barkio” recorded by Spike Jones and His City Slickers in 1947. A soprano, accompanied by piano, starts singing a credible version of Arditi’s “Il Bacio,” only to be first interrupted by, and then willingly accompanied by, the City Slickers howling and barking like a pack of dogs. This notion of Stalin-the-Spike-Jones-fan is unprovable but tantalizing. No doubt, he’d heard Donald Duck sing Spike’s greatest hit, “In Der Fuehrer’s Face.”

“Who collects the royalties for Mein Kampf?”

The first presentation of this work was in 1996 as part of a week of performances with Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s “Events” at the Joyce theater in New York. In advance of the series I had described the “morphs” between samples of Stalin and Lady MacMtsenk to the Village Voice’s dance critic. On the afternoon before the second “Events” performance, the company director approached me, saying “we have a problem…” It had occurred to me that the soviet-realist strains that survived the onslaught of Lemur and SoundHack might sound a tad too retro for Merce, but this wasn’t the case. Rather, Shostakovich’s ghost, in the form of a New York lawyer who looks out for his estate, wanted royalties paid for the use of the samples. For a moment I felt relieved that it wasn’t Stalin’s ghost, with a gun to the back of my head. Later it occurred to me that maybe Stalin, tyrant of the century, murderer of millions, doesn’t have a lawyer looking out for his interests – or does he? For that matter, who collects the royalties for Mein Kampf?

The six minute and sixty-six second piece presented here is a combination of various fragments from an hour long work of the same title. The speech and other sonic materials were analyzed, combined and resynthesized by a variety of digital audio tools including SoundHack, Lemur and MSP.

(c) 1998 Paul DeMarinis

1 “Death to the Russians!” was, claimed Stalin’s Politburo crony Anastas Mikoyan, the brooding Georgian’s customary toast during the late Forties. Witnesses for the Defence – Testimonies concerning Shostakovich’s attitudes to the Soviet regime by Ian MacDonald

2 At 3 minutes a side, 40 sides is still a whopping 2 hours long.

3 Conversations with Stalin by Milovan Djilas, Harcourt Brace & World, New York

Does humor play a role in your work?

To some degree, but the whole point of jokes is to crack open the unconscious. What then pours out is usually not very funny at all.

What’s the role of melody in your work? Does melody make your work more accessible?

Many of the melodies in these pieces derive from computer analysis of the natural prosodic contours of spoken language: from the liner notes of Music as a Second Language (1990)

“God is perhaps not so much a region beyond knowledge as something prior to the sentences we speak.”

– Michel Foucault

Hidden beneath speech’s words and music’s melodies I hear the singing of a voice more ancient than language. Brain’s secret convulsions making muscles articulate, shaking the world with a song now lost to us except perhaps in laughter, giving birth at last to a duality of sound and meaning. Now we can write or read, compose or listen, speak and converse even about our words themselves. No longer are we aware that as we speak our voices rise and fall, following the deeper contours of speech melodies that prefigure our sense and our meanings. Even our music ceased long ago to sing these melodies, following instead the steady course of harmonic progression. Still, as we read a text, we must reconstruct the melodies of the writer to grasp the meaning. Still, we code our feelings in the melody of our speech. And still, as our leaders talk, hearing not the words but the music, we sing our quiet selves into a sleep of understanding. The whistles of the birds in our nose, the creaking door which closes a phrase, the measured pause which precedes a two-beat putdown – all these underlie the choice and order of our words. These are the ghosts in grammar’s basement.

In many of my recent songs for synthesized voice I have treated speech melodies as musical material. By a process of computer analysis and re-synthesis I extract the melodic line of spoken language, involve it in a variety of compositional transformations, and apply the result to digital musical instruments. Along the way, the original voice becomes more or less disembodied, but retains much of the original spirit and meaning. With the computer analysis model I can alter voicing – changing the speech into drones or whispers, articulation rate – speeding or slowing the speech independent of pitch, as well as a variety of other effects, many of which sound unfamiliar but agree with the kinematics of the vocal tract. As I compose, I listen and I think. I choose vocal sources which interest me, particularly the voices of evangelists, hypnotists and salesmen because of their great confidence and enthusiasm. © 1990 Paul DeMarinis

Is there a reference to pop music in your work?

No – I have zero personal knowledge or connection to popular music or pop culture. Any figures that suggest popular culture are probably either playful allusions or parodies.

– Joeri Bruyninckx

Paul DeMarinis Official Website

Paul DeMarinis Bandcamp