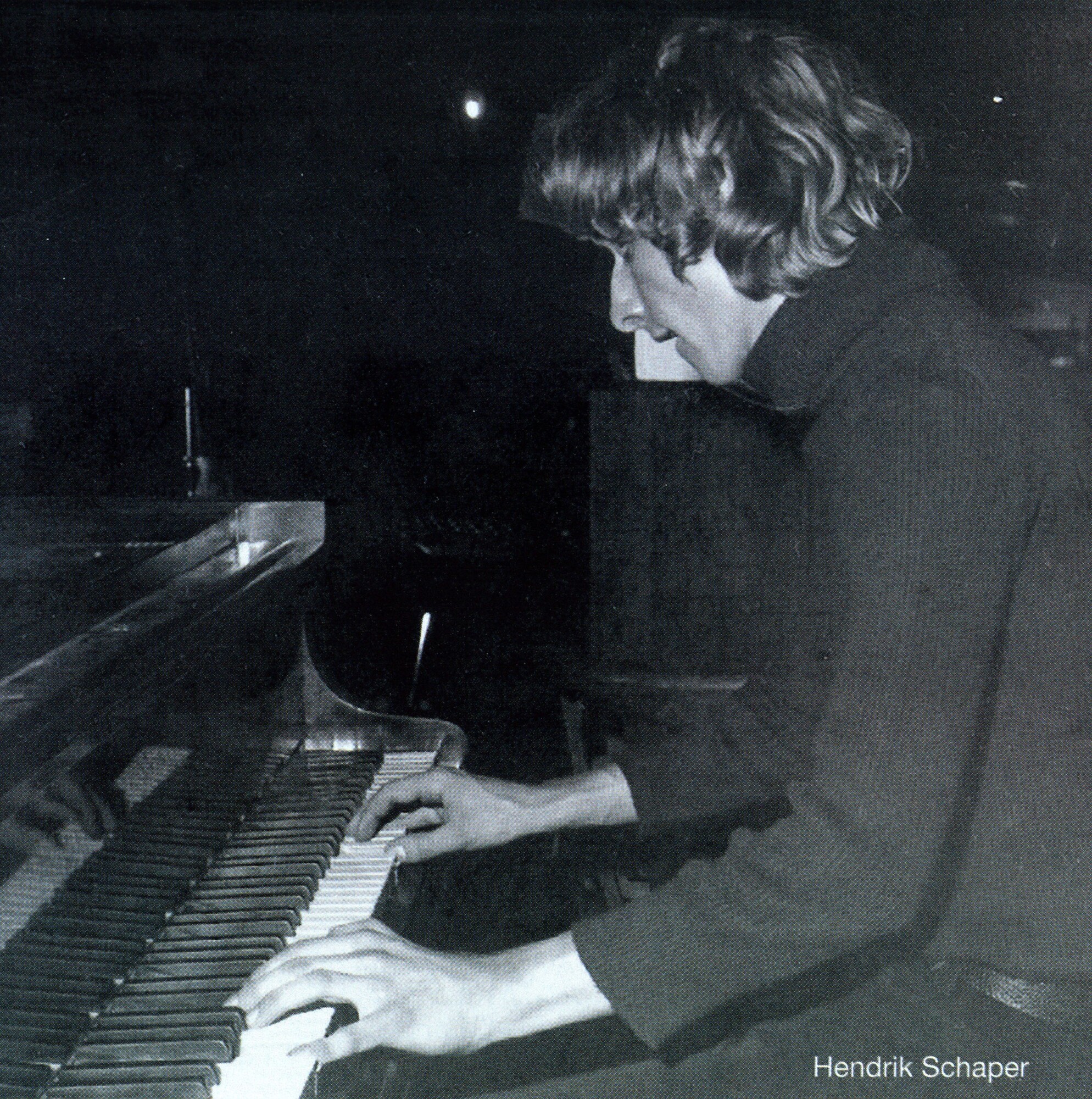

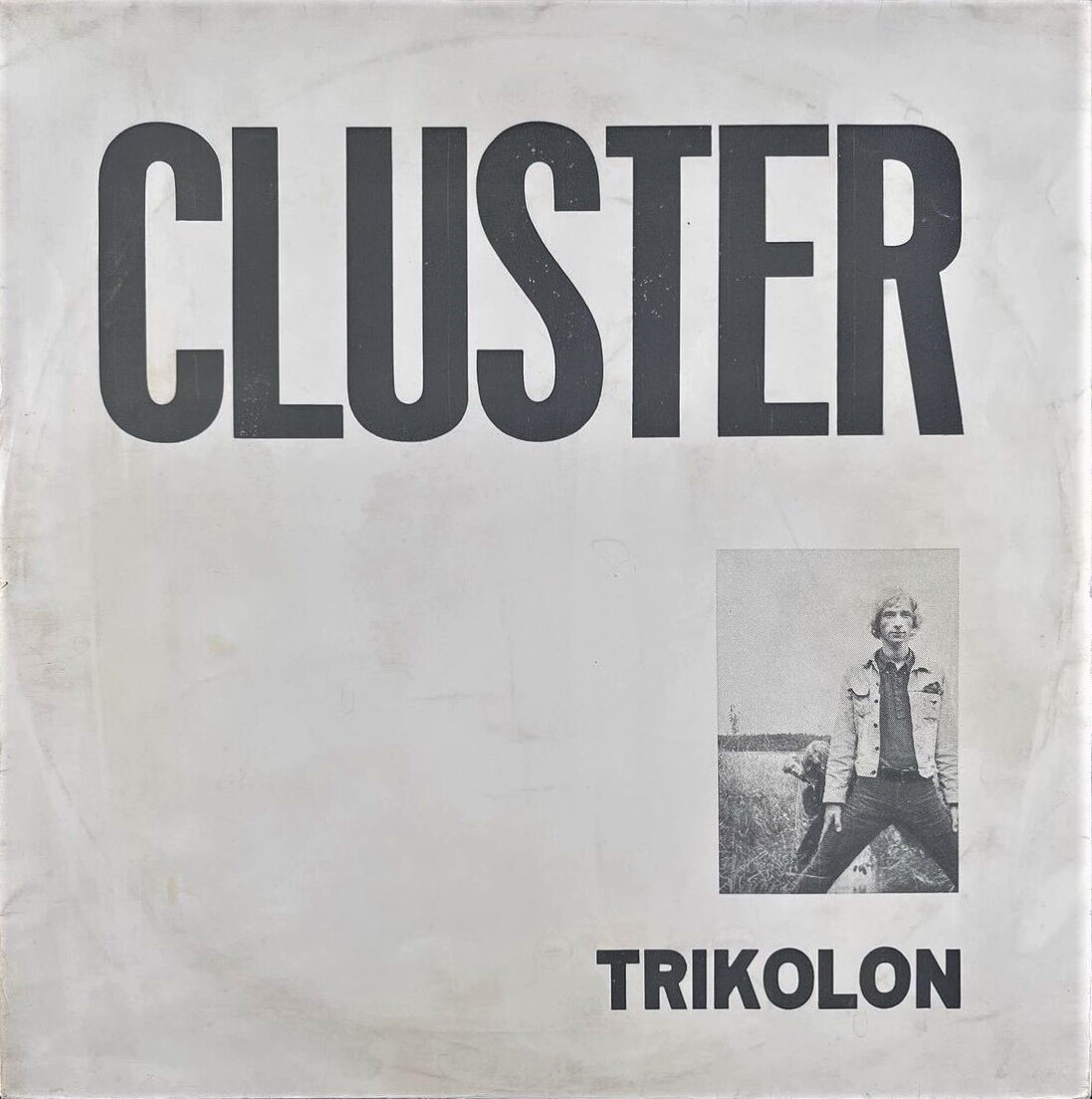

Trikolon | Interview | Hendrik Schaper | New Reissue of 1969 Album ‘Cluster’

The 1969 ‘Cluster’ by Trikolon is an underground classic of German experimental rock. The rare album gets an exciting vinyl reissue via Garden Of Delights.

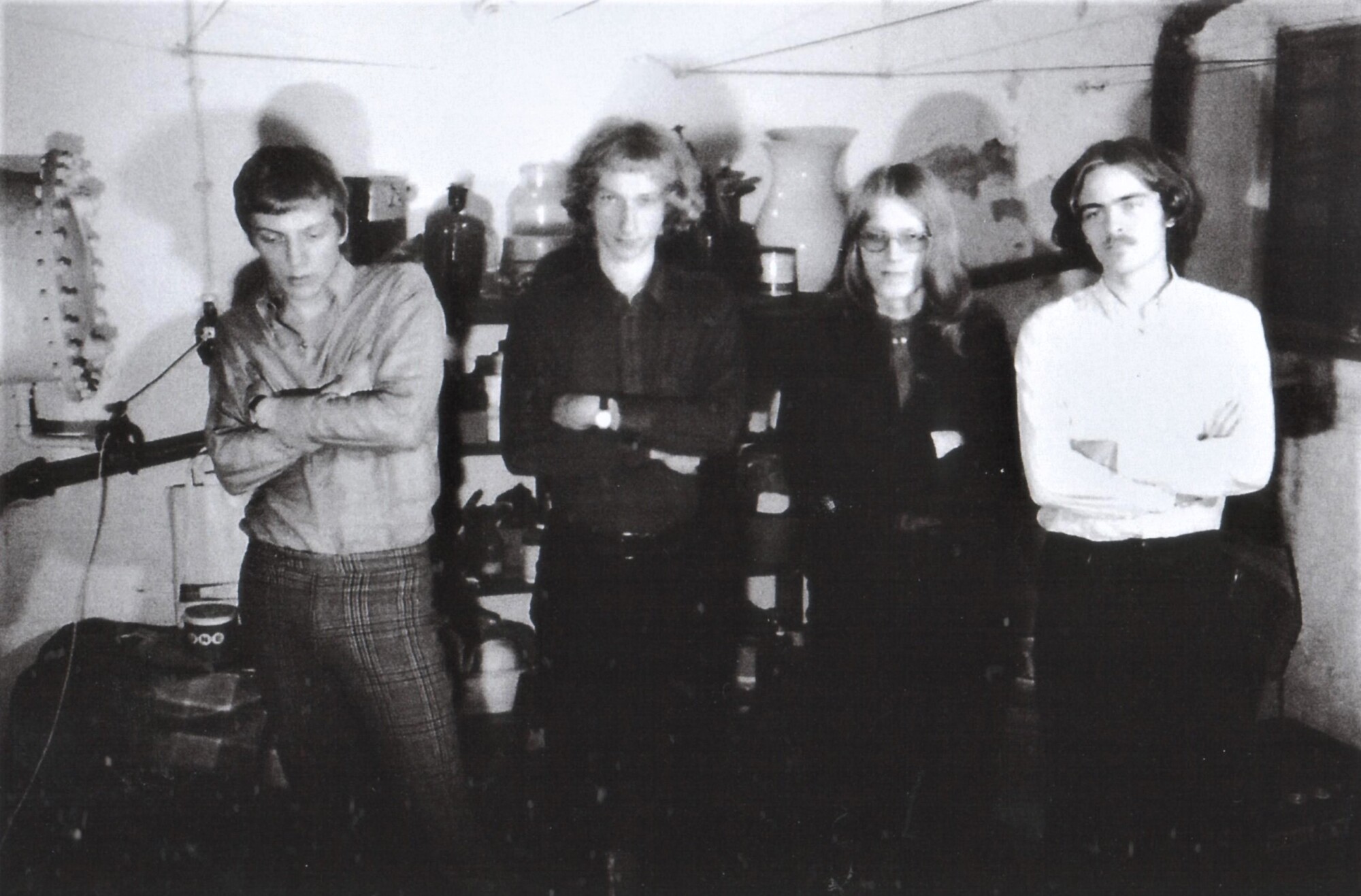

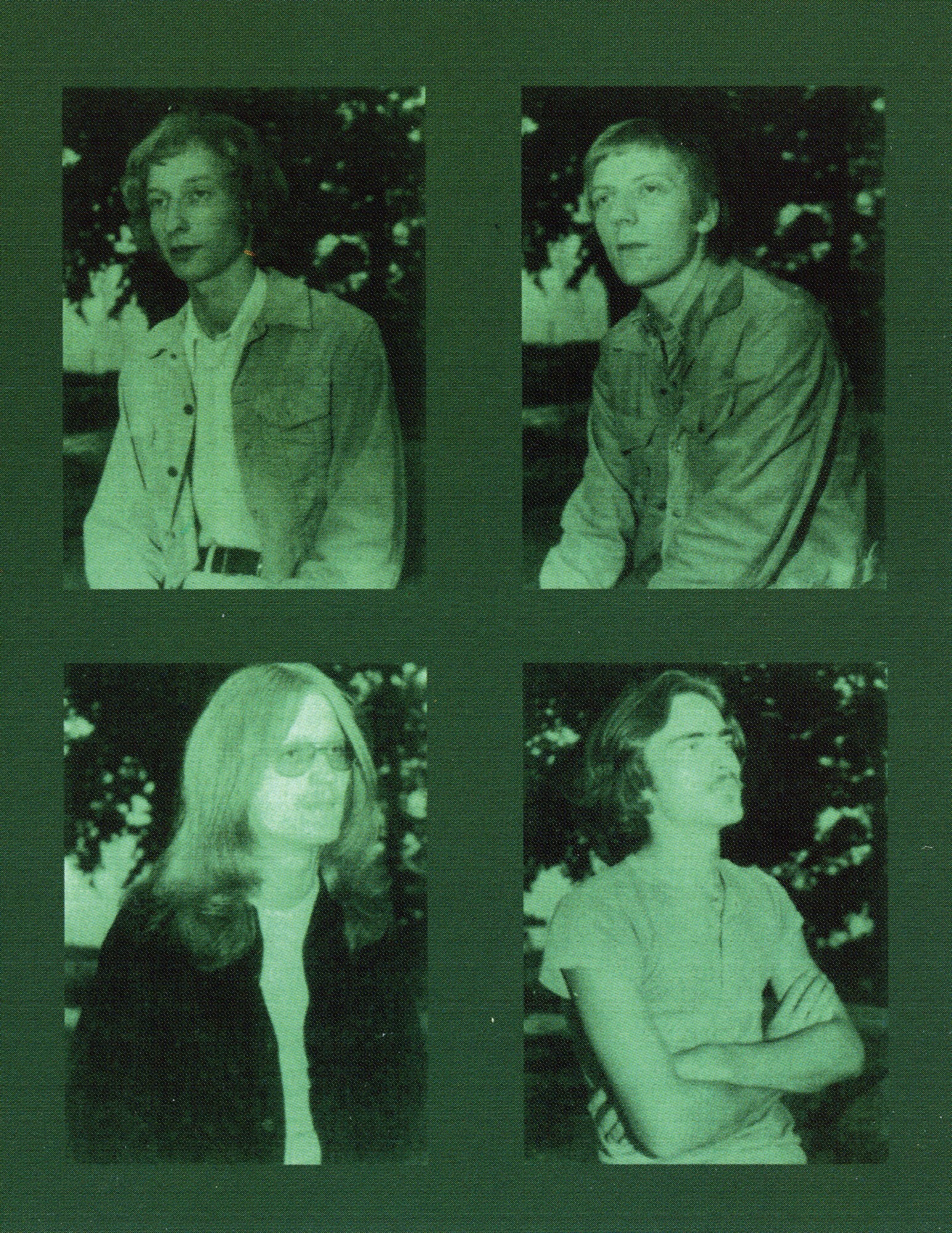

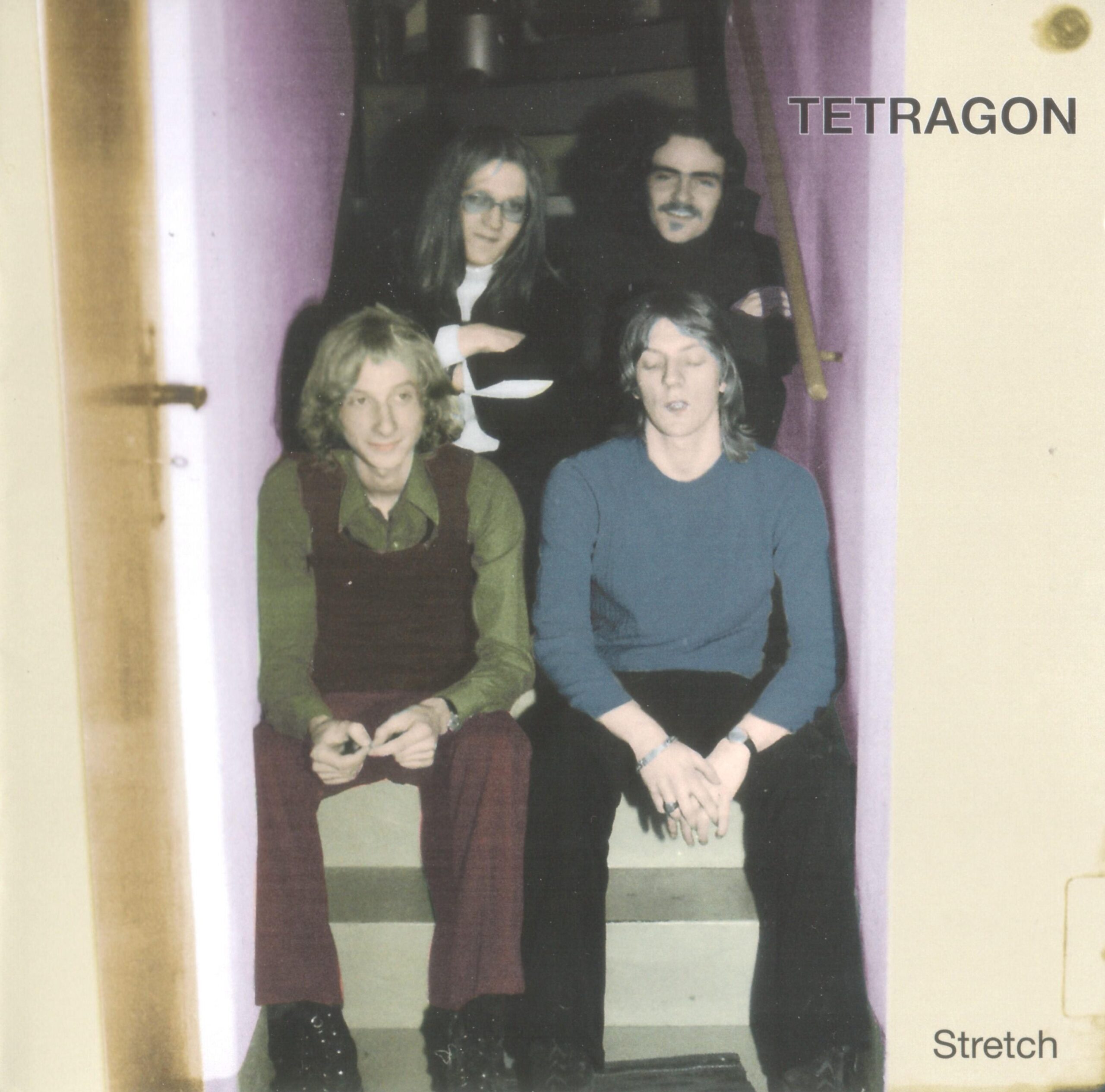

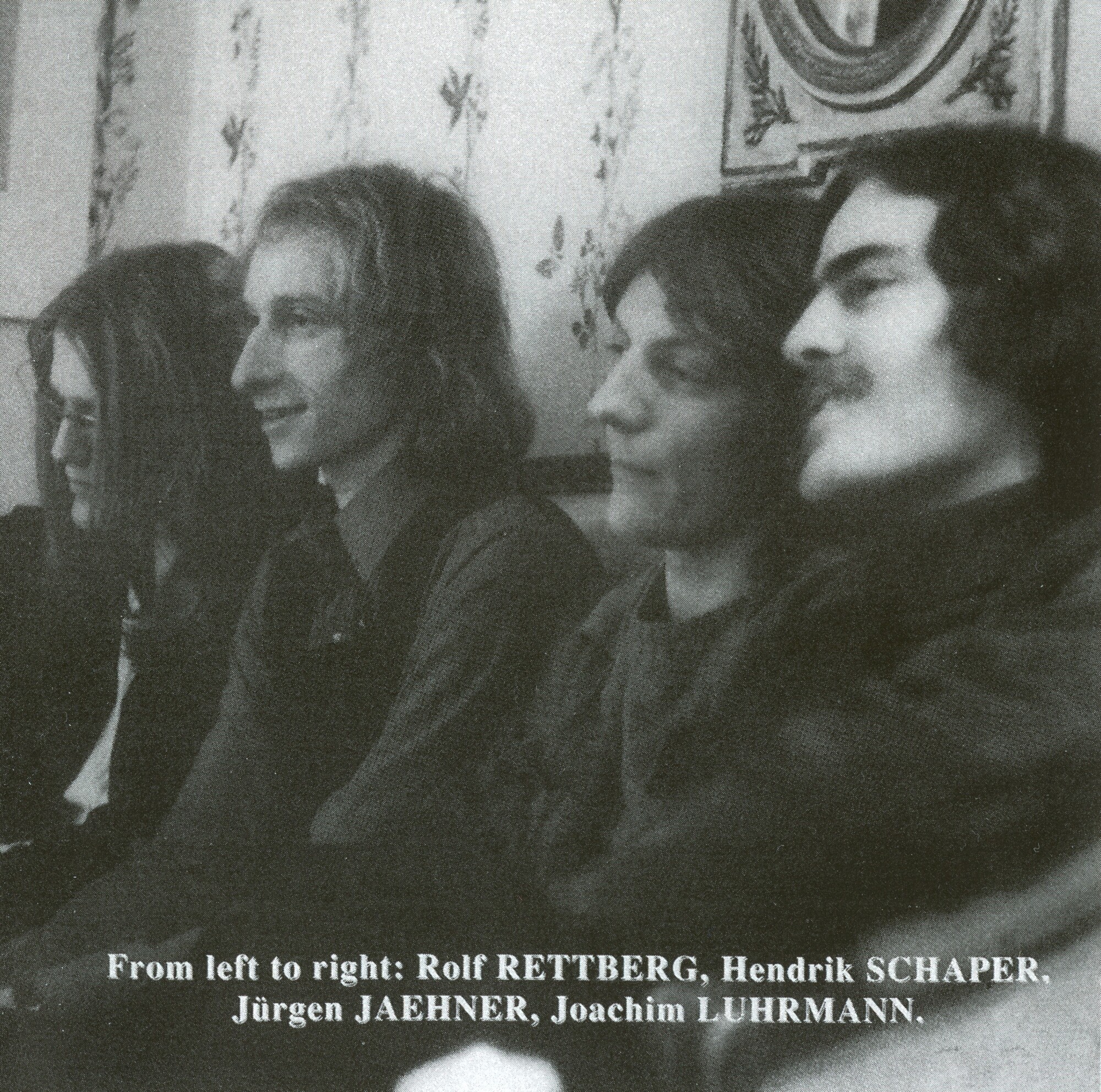

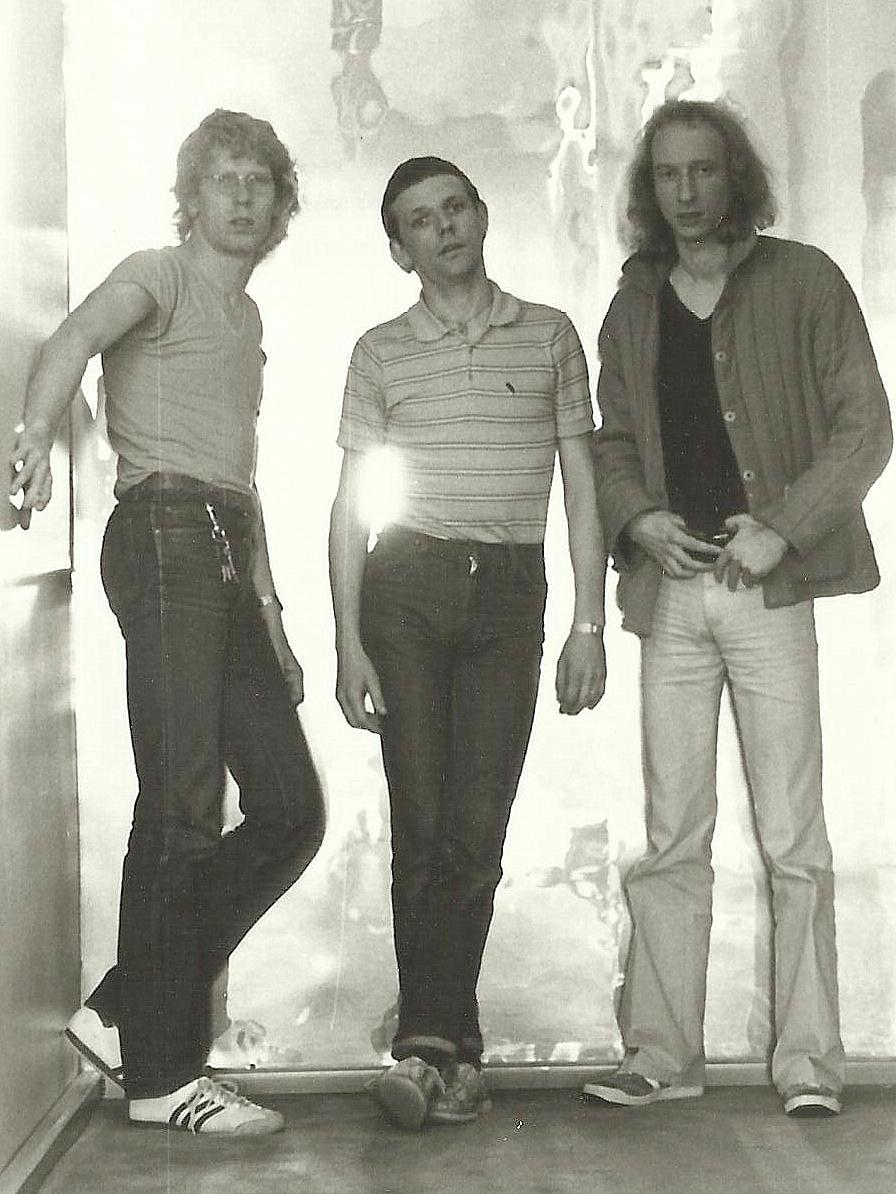

Trikolon was a very gifted trio from Osnabrück consisting of Hendrik Schaper, Ralf Schmieding and Rolf Rettberg. The roots of Trikolon go back to a band called Blues Ltd. formed circa 1966. Keyboardist Hendrik Schaper later also fronted Tetragon. The original LP ‘Cluster’ was released in 1969 in a run of 150 copies. Garden Of Delights issued a fantastic vinyl version with a 16-page booklet. Limited to 1000 numbered copies.

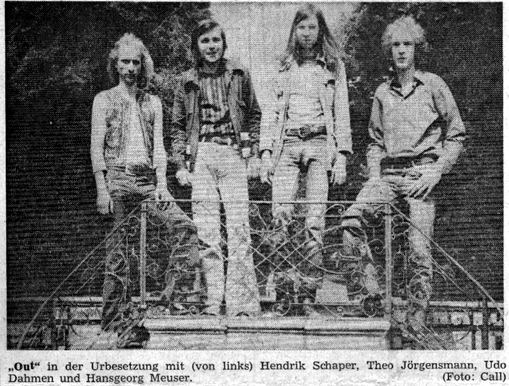

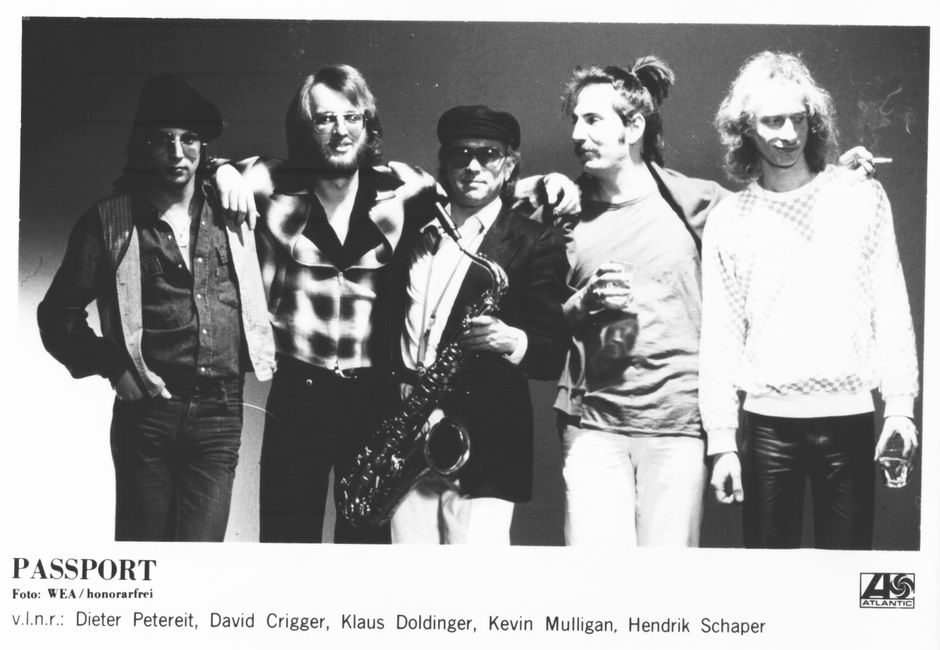

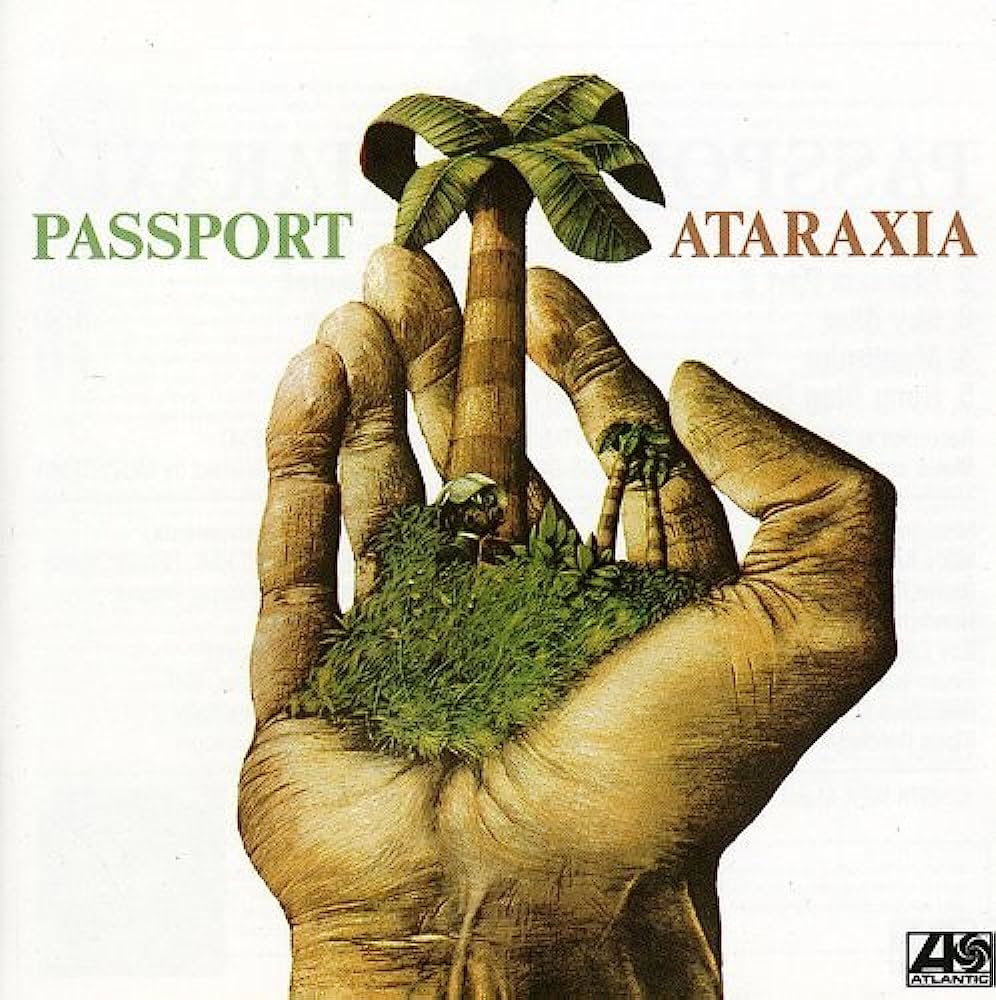

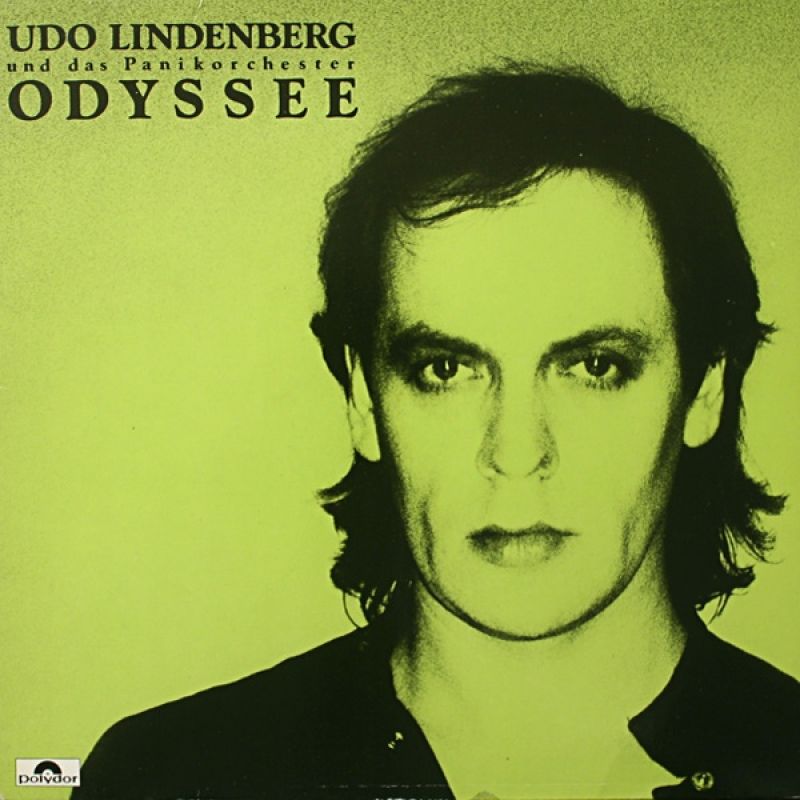

Hendrik Schaper began a career with the groups Blues Ltd., Trikolon and Tetragon. The first group he worked with nationally was the group “Out” in 1974-1975. The clarinetist Theo Jörgensmann, Micki Meuser bass (musician, producer of Ina Deter, Ideal, Die Ärzte) and Udo Dahmen drums (Kraan, Eberhard Schoener, Popakademie Baden-Württemberg) played in this band. He then started his national career with Klaus Doldinger’s Passport, in which he took part from 1977 to 1981. After producing his own album, ‘One or Zero,’ with Bertram Engel, drums, and Eddie McGrogan, vocals, which was released as “Lost Album” on Sireena Records, he worked with Heinz-Rudolf Kunze from 1980 to 1982 and from 1981 with Udo Lindenberg and his Panikorchester. He composed the music for almost 30 songs for Udo Lindenberg, as sole or co-author.

“Everywhere the music was opening up to more eclecticism, experimentation and colour”

One of the things that often gets mentioned when I asked bands about their early influences is a mention of Radio Luxembourg, were you listening to it while growing up?

Hendrik Schaper: Radio Luxembourg? Definitely! The German radio stations offered only a glimpse of what was actually happening in the middle of the 60s. So we youngsters had only two choices. The “BFBS”, British Forces Broadcasting Service, which was located near Frankfurt and gave us the British Charts every Sunday. That was a very important hour for us, also for taping the songs. The other choice was Radio Luxembourg, “the station of the stars,” as how they announced themselves. They played all the important music, but it was a challenge for us, because they were on AM (not FM), meaning prone to erratic reception, especially during the daytime. It was better at night, although still dependable of weather conditions. In good days it sounded quite ok, in bad days, you got phasing, dropouts et cetera, but we were still keeping our ears to the loudspeaker of our old radio, because who could resist listening to the new single ‘Gimme Some Lovin” by The Spencer Davis Group?

You were part of one of the very early experimental rock bands coming from Germany. Would you like to tell us what influenced Blues Ltd. to form? Where did you meet the other members?

Actually Blues Ltd. were not really an experimental band. The early influences came from the American blues singers themselves plus the young bands in Britain who also were influenced by blues. The more experimental style came after this band with the founding of Trikolon.

I’m guessing Osnabrück didn’t have much of a scene going on in the late 60s? Were there any clubs where you hangout with like-minded people?

At that time Osnabrück was not even a university city yet, so except for beat bands playing for dance, nothing was really happening. We were lucky to have the “Westend-Club,” a former sex-club in cellar rooms of a backyard of a bicycle workshop. This was self-maintained by students of an engineering school and not commercial. That is where Blues Ltd. had their quite wild performances, apart from a few other opportunities around town. Among the students and high-school students visitors were also soldiers of the British Army, since there were many of them stationed in Osnabrück at that time as a consequence of Second World War.

Are there any recordings of you playing in the Blues Ltd.?

There may exist some private recordings of the early Blues Ltd., but no official ones. Even I did not check my old tapes for any yet.

What would repertoire consist of at the time? Where did you play? What bands did you share stages with and what kind of instruments/gear did you have?

The repertoire consisted of blues and “city blues” songs by Ray Charles, John Lee Hooker, Muddy Waters, Slim Harpo et cetera. Often we got them actually “second hand” from records by the British groups like The Animals, The Yardbirds, The Pretty Things, The Spencer Davis Group et cetera.

The instruments at that time consisted of what was available for us money-wise. The line-up was bass, drums, guitar, and I played a piano whenever there was one, and a so-called combo organ. I started with a “Lipp” model (German), then a Yamaha with one manual followed, then a Lowrey organ with 2 manuals did the job for Trikolon later.

What led to the formation of Trikolon, which moved away from just blues influences towards more experimental, jazz-oriented tracks?

Trikolon was founded by the feeling of a need to expand musically. We were influenced by the blooming musical development of the British music scene (The Nice, King Crimson et cetera) and by the American jazz scene (Miles Davis, John Coltrane). Everywhere the music was opening up to more eclecticism, experimentation and colour, it was an exciting time.

“There was absolutely no “post-production” whatsoever”

What were the circumstances around the release of ‘Cluster,’ which was privately released in a limited edition of 150, if I’m not mistaken? Who decided to record the gig and what did the post-production in those days look like?

The recording of ‘Cluster’ was more or less spontaneously proposed by my brother Michael (born two years before me). The gig was a concert scheduled for a Saturday night at the “House Of The Youth,” a city-maintained small hall in Osnabrück. A young guy who was interested in electronics, Reiner Tylle, was asked if he would fancy to record the event. He did with a 2-track recorder. There was absolutely no “post-production” whatsoever. We brought the tape to a record manufacturing company “Pallas” in the nearby town of Diepholz. They probably had the main level adjusted for the pressing, and that was it. Meanwhile the sleeves and labels were printed at an Osnabrück-based company and I remember us gluing them together. With the “product” ready under our arm, we went to the three existing record shops in town and asked them politely to take them into commission, which they did. By the way, the “design” of the cover was done by my brother and a friend of my brother, Ingo Petzke. The name ‘Cluster’ was proposed by Ingo, who thought it was a good idea to use my occasional hits of the keyboard with the whole flat hands as a clue.

How do you feel that you managed to record some of the earliest underground rock albums in Germany as a very young man?

My bandmates and me did not have any thoughts about being among the first to make an early underground record. I think we did not even see the whole picture – we simply burned for the music and followed the proposal of my brother Michael to make the record. We were kind of “local matadors” and probably wanted to support that image with an own recording.

When you changed your name to Tetragon, was it basically the same band with its core members with additional or more musicians?

When we invited the wonderful guitarist Jürgen Jaehner to join the band, the name had to change, because a Trikolon is a unity of three, so it was logical to change to Tetragon, which is a unit of four. In my high school I was learning the ancient language of Greek, so I did not have to look up that new name.

What are some of the strongest memories from recording and producing ‘Nature’? Was there a certain concept based around mother nature?

The memories of recording ‘Nature’ circle around two days recording on 2-track tape in a barn in a decentral part of Osnabrück. It was Pentecost Fest and two days of holidays. We all played in the room like playing live to tape. The atmosphere was basically relaxed and joyful, but concentrated, of course. The barn belonged to an uncle of the drummer Joachim Luhrmann. We did not have to pay for being there the two days. I wrote the title ‘Nature’ because even as a young guy I was aware of how much satisfaction and recreation a walk through the woods and meadows around Osnabrück would bring to one’s body and soul. So I liked to express this kind of feeling with some words of mine. Back then I haven’t had good English knowledge. The sleeve design by Jürgen Osieka was supporting that idea and in addition tried to warn of the destruction of the natural environment by industrial and other discharges that would harm life.

Did you have any new audio gear around the time?

As a musician, no matter in which state of development, you always look for instruments to further your musical expression. Therefore you are always interested in which instruments were used on your favourite recordings, and you also watch other musicians in concert and, in addition, read attentively advertisings in music magazines et cetera. So, depending on the amount of money we had, we bought new gear if possible. The guitarist in Tetragon purchased a Gibson Les Paul one day, the drummer a Premier set, and I was proud of my Hammond L-100, which I even customized a bit – amplifying the attack noise and percussion sounds. For the album ‘Nature,’ I used a Hohner Clavinet D, the Hammond L-100 in conjunction with an electronic device by the company “Schaller,” which they branded “Rotosound,” to simulate a “Leslie” effect. It was at least affordable for me at that time and was sounding halfway to the direction of a Leslie. Later, for example, I was happy to buy a real Leslie speaker cabinet (a German brand though) for my Hammond organ, and a Fender Rhodes 88 electric piano, which I customised removing the rubbers from the wooden hammers in order to get a harder attack. These two new items were used for the practise room of the self-recorded album +’Agape,’ which was our last and, in my opinion best album we did.

Of course, for the album ‘Nature,’ I used a grand piano as well, which I will explain next, when I will go through all the numbers on the album separately.

Please share your insight on the albums’ tracks?

‘Fuge’ is, of course based around Johann Sebastian Bach’s Fugue in D Minor. We were influenced by bands like The Nice and Egg from Britain, or Ekseption from Holland, who all took excerpts from classical pieces and arranged them to their liking. That is basically what we did, adding vamps ourselves for solos and improvisations. The piece is quite long, but we recorded it from beginning to end in one piece without any stops or cuts.

‘Jokus’ is just the noise of one of those “laughing sacks” that were sold around the time. They had a battery and a mini loudspeaker and made this ridiculous noise, which we enhanced by a lot of spring-reverb.

‘Irgendwas’ is the German word for “anything,” and it meant for us: “Let’s do anything without bass and drums,” meaning Jürgen Jaehner and me playing electric and acoustic guitars, and acoustic piano and organ, respectively. This piece is cut together from two kinds of recording conditions. For the grand piano part, we asked the boss of the House Of The Youth, if we were allowed to use the one located in the dance and concert hall, which is, by the way, exactly the one I used for the live concert on the Tetragon album. For a part of the piano track, we processed the sound through a wah wah pedal right during the recording. The parts with electric guitar and organ were already recorded during the two days in the barn. The main theme of the piece (at the beginning, and at the end) is quite a complicated affair rhythmically, but through influences by other “progressive” groups and even “East Meets West” projects, we simply felt that it was fun to do that.

‘A Short Story’ is influenced and in parts derived from the West Side Story Medley by the Buddy Rich Big Band, which we all adored. Again, we added and switched own parts, so what came out in the end was a kind of jazzy “Short Story,” told after the West Side Story.

‘Nature’ has musically an influence by the style of Wes Montgomery. That “easy feeling” of the verses turns to different bits of style during the course of the song, up to an adaptation of a snippet of a Bartok folk dance, before the ‘Nature’-theme again concludes the piece. A friend of mine, Dirk Scheer, and me found the words for the theme to underline the recreational power of nature. I think the Clavinet D keyboard, which I play at the same time as the organ, is fitting in quite well for the overall sound here.

The CD bonus track ‘Doors In Between’ is a live recording from a later concert date around Osnabrück. It was conceived only after the recordings of the album ‘Nature’. The rocking groove is kept for most of the piece, and it was a nice springboard for the improvisations of guitar and organ. The quiet part in between features the sound of a Wurlitzer electric piano, which I purchased in Hamburg during the studio recordings of the album ‘Stretch’. The title is derived from Aldous Huxley’s book The Doors Of Perception.

The band played for quite some time, recording much more material. Would you like to share some further words about the ‘Stretch’ (2009) and ‘Agape’ (2012), which was released much later and sadly not back then.

‘Stretch’ was an album recorded in a real studio, the Windrose-Studios in Hamburg in the wintertime. The day we drove there in our cars from Osnabrück on the autobahn, we had heavy snow storms keeping us very slow. But the recordings started the next morning anyway. The recording was supervised by Rainer Goltermann, who was the manager of the German band Frumpy. After he had heard us on a gig supporting Frumpy, he proposed an album for the Philips label. After the album was in the can, we did not hear from him for quite a while. Checking further, we learned that the Philips label at that time was obviously not interested to release the record. A little later we also learned that the label was finished anyway. Our friend Peter Kretschmann much later somehow got hold of the tapes, and Garden Of Delights were interested in releasing them.

The recordings sound a little subdued to me, the reason may have been that a recording situation like that with the time-pressure was a first for us. Anyway, it was a good experience for all of us. By the way, 20 years later, I was working and co-producing for Udo Lindenberg in exactly the same studios for some years, by now they were named Chameleon-Studios.

‘Agape’ was a complete different story. We heard and read about the German producer Conny Plank and wanted to record a demo-tape for him. We did that in the small rehearsal room in my parent’s house with a 2-track recorder and our best instruments we had yet. We turned the volume up quite loud, but, maybe because of the small room, there was no reverb or other disturbing noise, so a little wonder worked for us to get quite a good amateur recording. It is our last recording, and we had developed a bit of musical experience and some compositions by then. At least for my taste, these recordings are our most advanced and energetic ones. Conny Plank’s answer was declining. By hindsight, we could understand that, because he was working in a bit of a different musical sphere. But Tetragon kind of disappeared from the picture after that, although we stayed friends.

What are some of the most important players that influenced your own style and what in particular did they employ in their playing that you liked?

The range of players who influenced me in those days was quite big, no matter if guitar, trumpet, flute, whatever. But if you like to know more specific about my instruments, for the organ I can definitely mention Jimmy Smith, Brian Auger, Keith Emerson and Steve Winwood. Jimmy Smith’s hot and bluesy style and his licks were irresistible. Just listen to ‘The Cat’ by him. Brian Auger played hot like no other. I first copied especially his pentatonic runs, which are hot and versatile in different modes. Just listen to his ‘Red Beans And Rice’ from the album ‘Definitely What’ by Brian Auger and the Trinity. Keith Emerson hit me when I first saw him with The “Nice” at the National Jazz & Blues Festival in Sunbury on Thames in 1969. The band, still a 4-piece, played ‘America,’ and Emerson’s versatility and energy was immediately obvious. Also, his heavy use of quart chords, which I heard already on John Coltrane’s record ‘Ole,’ impressed me a lot.

Just listen to ‘For Example’ on the album ‘Nice’. Stevie Winwood’s genius was obvious right from his beginnings in The Spencer Davis Group, when he was just 17 years old. He is one of the “coolest” keyboard players in rock. For early examples just listen to ‘On The Green Light’ and ‘Nobody Knows You When You’re Down And Out’ on the Spencer Davis Groups album ‘Autumn ’66’.

Tell us how did you, Theo Jörgensmann (clarinet), Micki Meuser (bass) and Udo Dahmen (drums) come about to play in a very interesting project called Out (1974-75). Did you record anything? Did you do any shows? What kind of material did you play?

All the four early members of Out, met actually at a jazz-workshop in the middle of the seventies near the city of Remscheid. This workshop was held every year in summertime for a month at the Akademie für musische Bildung und Medienerziehung. You could apply for the course by writing to them about your musical preferences and education and development. If you were accepted, you paid a small fee for the workshop (it was supported by the state of Northrhine-Westfalia). The good thing about these workshops was that the teachers were all first rate German jazz musicians. In the daytime there were classes, and in the evening you could meet and play with whomever you liked. So that’s how Out met and hit it off immediately with energy. So we went on and rehearsed sometimes in Gladbeck, Aachen or in Osnabrück, about once a week. Everybody had a car, so the distances were not really a problem. We played some compositions by H.G. Meuser, the bass player, and by me, and by Theo Jörgensmann, mostly as starting points for very energetic, electric improvisations. Theo’s clarinet was electrified (amplified and going through effects, and I used my very first synthesizer, Moog Sonic Six). And yes, we played in a lot of jazz clubs all over Germany, and after the Quartet was reduced to a trio, since Theo was very busy going solo, we had recordings for Radio Stations NDR and WDR, two of the few big stations who ran regular jazz broadcasts. I remember we also played in Cologne open air in front of the dome. Anyway, before we thought about a real recording, Klaus Doldinger contacted us because he was looking for a new line-up of his well established jazz-rock group Passport. After meeting him and playing music in his studio in the Alps, he put the new line-up together and asked me to join.

What led you to join Passport and what do you recall from working on ‘Ataraxia,’ ‘Garden Of Eden,’ ‘Oceanliner,’ ‘Blue Tattoo’?

With the new line-up of Passport in 1978 rehearsals took place in Klaus Doldinger’s studio which was a detached extra house on the grounds of his residency in the idyllic village of Icking in the pre-Alps, south of Munich. With three Latin and three European musicians in the band, it was an exciting and interesting start for the upcoming concerts and albums. I played the Fender electric piano, my Minimoog, and an RMI Organ. Klaus Doldinger had picked a band which was quite capable of rehearsing and recording quickly, which is a good thing for freshness and spontaneity of the material and the solo improvisations. That is why it always stayed interesting and fun to rehearse and record the albums ‘Ataraxia,’ ‘Garden Of Eden,’ ‘Oceanliner’, and ‘Blue Tattoo,’ and, of course the live-double album ‘Lifelike’ which was recorded at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 1980.

Our performance on that evening was sandwiched right between Van Morrison and B.B. King, and was an exciting experience. Another great experience with Passport was the concert tour across the U.S.A. in 1979, starting at the famous Bottom Line Club in New York City, crossing clubs and concert halls of the whole country, landing in L.A. to play the Roxy Club. The tour lasted about one month all in all. Most of the money I had earned there went into a new instrument, the ARP Quadra, which I purchased in the West L.A. Music-Shop and brought home afterwards.

Tell me about your collaboration with Heinz Rudolf Kunze?

In 1980, I still lived in my hometown of Osnabrück. So was Heinz-Rudolf Kunze. I don’t remember meeting him up to that time, but he had just landed a record contract with Warner-Electra-Atlantic and was about to record an album. So he tried to put a band together of musicians from Osnabrück. The drummer was, by the way, Joachim Luhrmann from Tetragon. He asked me to join, and the band rehearsed and prepared for his first album. Since Klaus Voormann, the great illustrator and bass player, was producer for WEA at that time and had a huge success with the release of ‘Da Da Da’ by Trio, he was convinced to play bass on the record and came to rehearse with us. The album was recorded in Hamburg, and during the mixdown sessions Klaus had the opinion that his bass parts sounded a bit too muffled, and he did not want to overdub, so a bass player from Osnabrück did the overdubs. Anyway, I did some albums and tours with Heinz-Rudolf, until I was approached by Udo Lindenberg to join the Panikorchester after I moved to Hamburg.

Did you get in touch with Udo Lindenberg through Passport as he was their drummer early on?

Udo Lindenberg had been the drummer in Passport, but in an earlier time and line-up. So the connection to him did not happen through Doldinger, but through Bertram Engel, the drummer of Udo’s band. He lived only 50 km from Osnabrück, namely in Münster, and once we met by chance and talked. That was in 1980 still during my time with Passport, and he was delighted to meet somebody from that band and proposed a jam session. That took place in my parent’s house, and was exciting for all musicians participating. Since around that time Udo Lindenberg was looking for some keyboard player who would play the synthesizers, and Bertram proposed me. I remember Udo standing backstage right behind me once during a concert with Passport in Hamburg and checking me out. After the encore he asked me directly to join his Panikorchester. The lone fact that Bertram was a great drummer would have lured me into the band, but there were other attractive reasons, among them the other musicians in the band, and the fact that Udo is simply such a great artist.

As being such a big part of Udo Lindenberg, what are some of your favourite memories? You composed around 30 songs for him.

The first album I recorded with and for Udo Lindenberg was ‘Odyssee’ in 1982. My album ‘One Or Zero’ was recorded at that time, but not released. But since Udo had heard it and liked the composition of ‘Small Town Man’s Romance,’ he asked me if we could record it for ‘Odyssee’. I agreed and he, naturally, wrote German lyrics for the song, which evolved into ‘Kleiner Junge’. So that was the beginning of a mutual respect – for my compositions from his side, and his lyrics, from my side. And this collaboration continued for decades to come. The method of working together was not necessarily a formula – it could also happen that he had a lyrical concept for a song and asked me if I had an idea to put them into music, and vice versa. Still nowadays, when we do ‘Goodbye Sailor,’ for example, I think we both get a bit sentimental during the performance of our common creation. A great feeling.

Since you ask me about favorite memories, it is not easy to pick only a few from a time span of 40 years, but I definitely keep all our concert trips even outside of Germany well in my mind. With Udo we’ve been to Moscow, Warsaw, Beijing, Shanghai, Vienna, and so on. And for Germany – in the last decade the concerts were mostly stadiums, for example we played the Olympic Stadium in Berlin with an audience of 70.000 people in 2019, and also big-capacity halls all over the country. Also the trips with The Rockliners, five up to now, were very special. A whole cruise ship with around 3000 Udo-fans on board, leaving from Hamburg to Spain and back in one week, where we gave a concert in the theater (capacity circa 800) every night during the trip.

Would you like to talk about your solo album, ‘One or Zero,’ you did with Bertram Engel (drums), and Eddie McGrogan (vocals)? (Released as ‘Lost Album’ 2014 on Sireena Records)

As I said before, the album ‘One Or Zero’ was recorded in 1981. It happened in the garage of my parent’s house with only me putting all the instruments on an 8-track machine. And in a professional studio in Hamburg for overdubbing the drums by Bertram and, finally, the vocals by Eddie. The project was supposed to be released shortly after the recording. The problem was the trend among record companies in Germany at the time. The “Neue Deutsche Welle” was the new thing, and it was understood that this sparse new style had vocals in German language only. Well, the musical style of ‘One Or Zero’ would have likely fit into their mould, but the vocals were in English, which was always my preferred one for rock and pop music.

So, no deal at that time! Then, even 33 years later everybody who was listening to the recording was quite excited about it. It came to my mind that by sleeping in the drawer nobody would be able to appreciate the record except my personal friends. I asked Walter of Garden of Delights, who had already re-released Trikolon and Tetragon, if he had a proposal for a publication. He recommended Tom Redeker of Sireena Records, who immediately agreed to release the album. The year was 2014. The album was born out of a certain time and preferences of styles in 1981, but even nowadays it is appreciated by listeners for power, groove, diversity and colour.

What’s your connection to the groups The Rattles, Elephant, Falckenstein?

Siegfried Loch, long-time producer of Klaus Doldinger, called me up one day in 1990 and asked if I would like to do musical arrangements for the German group The Rattles. They were planning a kind of a reunion album after their leader and singer Achim Reichel had gone solo for some years. My task was to write arrangements for a brass section, and coproducing the recordings in the Peer Studios in Hamburg. The album was named ‘Painted Warrior’.

Elephant was a group in Hamburg, and one of their founding members, Detlef Petersen, got more and more into scoring music for films, so they needed a replacement on keyboards. I recorded one album with them in 1985, called ‘Just Tonight,’ and played many gigs with them mainly in the north of Germany.

Falckenstein was a band located in Osnabrück with a German folklore style and a variety of string instruments. Joachim Luhrmann was their drummer, and he eventually asked me to help out for some keyboard parts for record album of theirs.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time playing in all those bands? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

Let me pick 3 highlights out of all the concerts I participated in:

The jazz festival in Montreux had an enormous reputation among international musicians and groups. Who does not own at least one recording of “…live in Montreux” by one of his favourites? On the evening before our show we had a drink in the cellar club of the Casino, the concert hall. And there many of the stars participating in the festival were hanging out: Stanley Clarke, Simon Phillips, Van Morrison, B.B. King and so on. So for Passport, the excitement grew till the next evening, and I think that resolved into an energetic set of our performance.

In 1985, Udo and the Paikorchester were invited to the World Festival Of The Youth in Moscow. Many friends, mostly artists like writers, actors, and also family members were accompanying us for this very special trip. Gorbachev had opened the country with his “glasnost,” and the city was well prepared for the event. The main concert happened in the main open-air stadium in Moscow, and over there the very famous singer Alla Pugatchova joined us during our concert to sing Udo’s song ‘Wozu sind Kriege da?’ with him and us. On that occasion she invited us to her home for the next day. During our two week-stay we also played concerts in other venues in Moscow.

Our concert trip to China in 2004 was definitely an exciting and eventful journey. Udo’s latest project Atlantic Affairs, which was not only a concert, but also a complete story told and acted onstage. This project was performed twp times in Beijing as well as Shanghai in huge theatres. Joining us onstage was also the Chinese political singer Cui Jian, who was known for having created songs to protest the massacre on Tiananmen Square in 1989. In our free time everybody roamed the cities driven by curiosity for this part of the world where nobody of us Europeans had been before.

Is there any unreleased material you would like to see released?

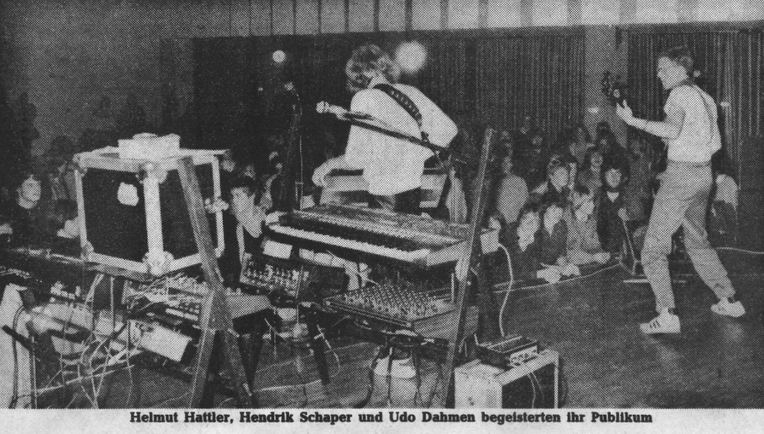

There are quite a lot of live-tapes and cassettes, directly from the mixing board from nearly all the bands I played in. By the way including from a tour I did with the bass player Hellmut Hattler (from the group Kraan) and the drummer Udo Dahmen (earlier with Out, later also with Kraan). The project was named Hattler-Schaper-Dahmen and did a tour through Germany in 1981, if memory serves me well. But all these recordings may have their highlights and energy, but would probably be of not that much interest for, let’s call it “the public”. A DVD of Passport’s Montreux performance would be a nice release, though in parts it is on YouTube since quite some time anyway. So basically – no, I don’t feel a special urge for early material to be released.

How did Die Chillies come about?

The Chillies came about because I greeted some of the so called “chillout” music at that time as a relaxed, creative, quite open and eclectic style of modern music. Only the element of improvisation was a bit too reduced in the music that I heard, and so I talked about another approach to that style to my friend Günter Haas, an experienced guitarist. We founded a project called The Chillies, a line-up of bass, percussion, guitar and keyboards. Our album of the same name was recorded live in the living room of the percussionist Conny Sommer within three days. Three female guests were also invited to sing and play on certain songs. A bit of editing, but not much, and mixing was done within another three days, and the album was ready. A deal with a record company was not intended, though we would have liked a bit more spreading through the internet at that time.

What about Cinemascope?

Some years later, only Günter Haas and me decided to change the project into Cinemascope, with basically him and me doing the framework, and then invite all kinds of good musicians from all kinds of styles to play, sing, and improvise over the music. That happened in my living room in Hamburg, and it worked wonderfully in a relaxed and creative way. Hence the name “Cinemascope,” because that was the brand name of a technique of a wider screen in cinemas in my youth. For example, we had musicians as diverse as my old musician friend Theo Jörgensmann joining on clarinet, a friend of mine from Kolkata, India, Rohan Dasgupta on sitar, and an acquaintance of mine, Ciao Lu, a Chinese opera singer from Beijing, singing.

What currently occupies your life?

Fritz Rau, the great German impresario and music lover, who did so much for the music scene, also internationally, once said to me while I was doing an album with Udo Lindenberg in a Hamburg studio: “You know, music is not only food to live, it is actually food to survive!” And I couldn’t agree more, since I know, at least for me, it is valid.” So, even if there is no tour with the Panikorchester this year, I get my musical food every day through playing the piano. That keeps me in demand, stimulated, and going without collecting rust mentally and physically. Even when I’m travelling privately, I carry a foldable 88-key keyboard with me. There is always something to learn, discover, develop, compose and practise and go forward. I am blessed to be able to do that in the present, and hopefully, in the future.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you, Klemen. Your perceptive questions gave me the opportunity of reminiscing about my past and development, and as a result I enjoyed working on this interview for you.

Headline photo: Trikolon live | Ralf Schmieding, Rolf Rettberg, Hendrik Schaper

Hendrik Schaper Official Website

Garden Of Delights Official Website