Red Krayola | Interview | Mayo Thompson

Mayo Thompson is an American musician and visual artist best known as the leader of the avant rock band Red Krayola that formed in Houston, Texas in 1966.

The band was part of the 1960s Texas psychedelic music scene and were signed to independent record label International Artists. Red Krayola was a project filled with experimental approaches often employing noise and free improvisation.

Drag City Records recently issued the latest book written by Mayo Thompson. After Math is the sequel to Thompson’s 2018 novella Art, Mystery. After Math retails what becomes of the cast of characters introduced in Art, Mystery, joint and severally pursuing an erotic Rinascimento statuette attributed to Antonio Pollaiuolo, a pursuit that lands them in court. On the way, their collective and singular fates are unfolded and accounted for, the consequences of the truth of matters for them are brought to bear and a kind of rough justice is seen to have been done, as is appropriate in rough trade.

“We aspired to make original stuff”

It’s really wonderful to have you. How have you been in the last two or three years? It seems that the world is changing at a faster rate than before? Were you affected by these changes?

Mayo Thompson: Kind of you. I’m getting by, thanks for asking, and for your interest. Are things changing faster? I don’t know. The pandemic was a game changer. I didn’t make a dollar from January 2020 until the other night. I mask up, depending.

Have you found the isolation creatively challenging or freeing?

I find practically everything challenging every day no matter what I’m up to, alone or with others. Freeing? No.

Would love to hear what is your most recent project?

Rewriting the music to a song Art & Language and I started work on in 2014—‘Born in Flames II’.

Let’s go back in time and discuss your very early years. What was it like to grow up in Houston?

I’m no good at stuff like that. Leave it at that, as I grew up, I wanted out eventually, and, eventually, left.

Do you recall a moment when you knew you wanted to become involved with music and art?

No. I sort of fell in? Both were around. My mother taught English and art in high school, and had an ear for music. She had records by all sorts—classical to contemporary. She could sing but never pursued it. Her older sister trained for opera. Sadly though, she died young. Mother’s friends were all sort too—artistic and musical people, some horsey people, a couple of cowboys, some athletes. I drew more than I painted as a kid. In military school I had piano lessons and played the bugle. I started to get serious about music around 1963 and was playing for money by 1966. I’ve been formally professionally involved in visual art since The Red C(K)payola was in the 2014 Biennial at the Whitney Museum of American Art.

You already had a band at the end of the 50s, would love it if you could tell me about it. What kind of material did you play?

“Band” is a stretch. I’ve mentioned it in the past because that’s what we were thinking—maybe this will answer part of your question about what made me want to get involved in music. A schoolmate and I jammed once when we found ourselves alone in the music building—at that military school I mentioned? He played trumpet, broke it up, thumping a drum and shouting. I pounded C major on the piano. We were listening to black rock ‘n’ roll records. ‘Work With Me Annie’ was my favorite.

You were studying at University of St. Thomas? What was the scene like back then in Texas for a young musician?

There was plenty to hear—live, on the radio, walking down the street—black, white, blues, jazz, r ‘n’ b, rock ‘n’ roll, classical, country, folk. And there were opportunities. I started singing three songs at La Maison, a folk joint until ’66, when beat music took over, after the British Invasion, and bands played.

How did you originally meet Frederick Barthelme? Did you have a certain vision from the beginning of what Red Krayola should sound like?

A million dollars worth of nothing quite like anything you ever heard before. Joking. We had no vision. We just started. When I first asked him about a band, he wasn’t interested. He was an artist—ideas out of painting, performance. We met in 1963. I met his brother, Steven, first. He said we should meet. One day I found a note from him under a windshield wiper on my car saying we should meet, so we did, and got on. We aspired to make original stuff, though we did do some covers for a while, but were working on stuff of our own from the start.

It would be a fascinating insight, if you would discuss what your creating process is like? The lyrics consist of free floating patterns without any direct narrative, while the music is really difficult to describe, but if one one word comes to my mind is “unique.” How do you feel about improvisation? Do you feel it’s a big part of who you are?

I’m no good at accounting for my way of working. Broadly, sometimes I have an idea of some music, sometimes words, sometimes they come together. I freely associate in both and, occasionally, do narrative. Improvisation I appreciate as a mode for itself, and for the role it can play when different minds meet looking for related conclusions.

“My sonic world isn’t unique—all sonic worlds are. Mine is singular.”

One of the things I really love in your work is that you don’t really care what critics think and I think that leads you to your very own sonic world.

Please. I care. I ask for it. I aim to interest, and leave pleasing, to fortune. I learn from it. My sonic world isn’t unique—all sonic worlds are. Mine is singular.

Texas had its own thing going on in the 60s with 13th Floor Elevators and Vulcan Gas Company in Austin, did you ever consider yourself to be part of that scene early on as it seems you were rejecting being listed as part of the counterculture that was going on?

We were in Houston. We never played Austin. As for counter-culture—the idea never appealed. In dialectic I think negations have to be negated too.

I once read that you enjoy Legendary Stardust Cowboy, Joe Fahey and the early work by Country Joe & the Fish, what are some other “out there” music you enjoyed at the time? Ornette Coleman, Albert Ayler, and do you feel it influenced you to a certain degree?

“Out there” music—nice. If you please, I’m no good at favorite’s lists—though something the Lege [Legendary Stardust Cowboy] said remains a favorite thought. When asked for a comment on something philosophical by a journalist I’ll call “John” for the sake of the story, he said, “You know, John … life confirms Hegel.” As for influences, I owe lots of people plenty, among them, those you mention.

What can you tell us about some of the early audio gear, effects and instruments you had in the band and when did the band get together to begin playing? What are some of the clubs you played?

I’m not much on tech. Electric I play either a Fender Stratocaster or Telecaster, or Gibson ES-175 through a Fender Twin-Reverb with JBL speakers. For effects I use the reverb and tremolo functions built into the amp. I don’t use pedals. Acoustic I play a Gibson L7, or one of three Spanish guitars—two flamenco, one classical. Clubs? The Crayola played Love, Catacombs, The Vault, Love Street Light Circus and Feelgood Machine. A later band—The Rocking Blue Diamonds—played The Old Quarter, and Rocky Hill’s Club.

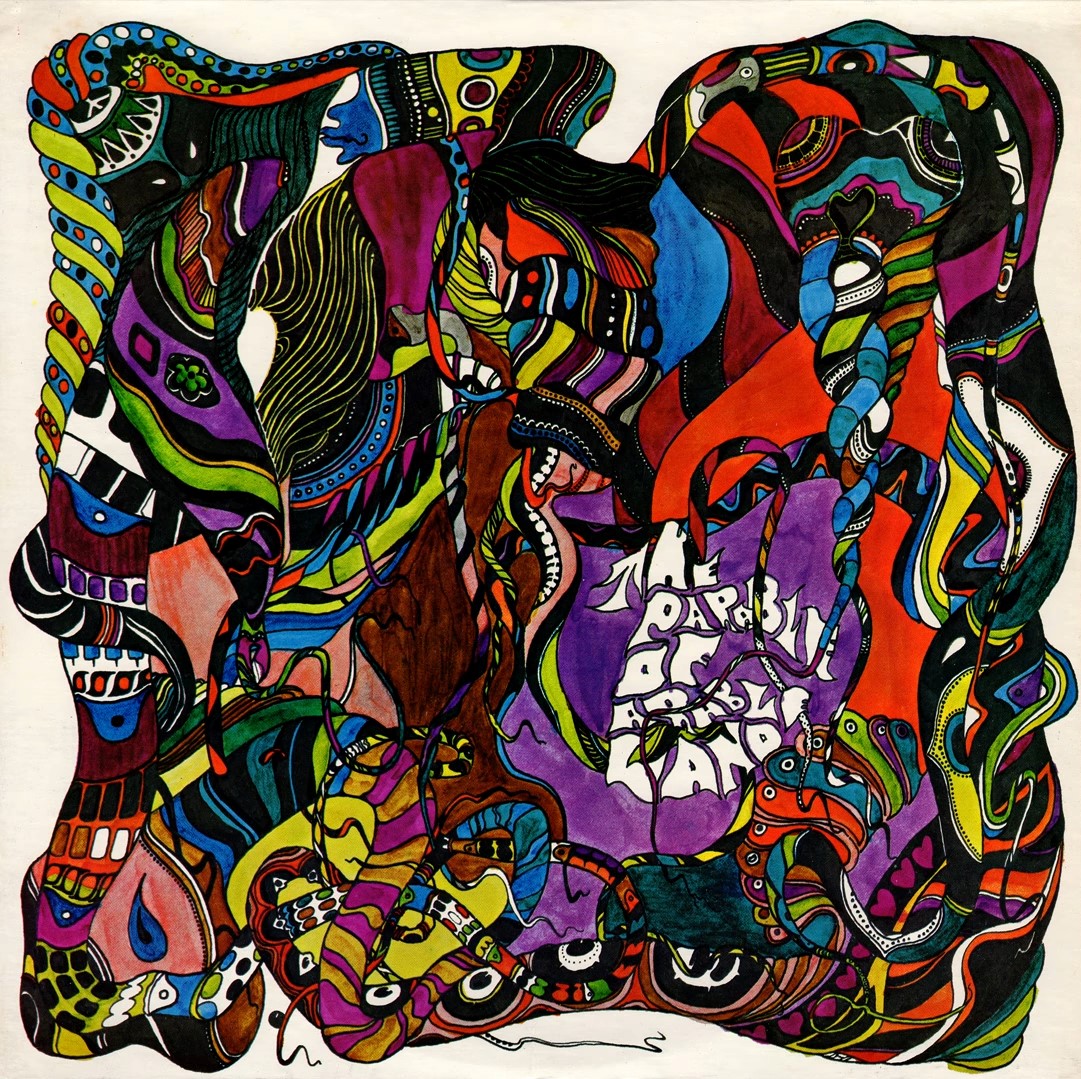

I would love it if you could elaborate how you got signed to International Artists and what are some of the main ideas behind ‘The Parable of Arable Land’? Do you see it as a conceptual art?

International Artists signed us after our first producer, Lelan Rogers, heard us play in a mall as part of a battle of the bands staged by a local top-40 radio station. The idea is what you hear—the facts— freakout—song—freakout—song et cetera. It’s an historical record of what we were doing, incorporating what was going on while we were doing it. It represents our inquiry into what all it is possible to take for music. As for conceptual, the concepts involved are artful but, no, I don’t see it as conceptual art.

You were friends with another experimental group by the name of the United States of America. Was that in California? What led you there and would love to hear a few words about Joe Byrd and Dorothy Moskowitz.

After the Crayola died the first time—after playing the ’67 Berkeley Folk Festival—I went back to California. I lived in Venice and was jamming with two players I knew from Texas, a drummer and another guitar picker. We shared rehearsal space there with the United States of America. Joe Byrd and I found what to talk about. His reputation—the Cage connection, his politics, his way of thinking and living—we got on fine. There was respect, I think—he told me he would have asked me to join if I could sightread—alas I can’t. He knew well what the Crayola had done—what it represented in the scheme of things. He asked me to bring a guitar to help him test some amplifiers they were thinking of getting. I handled the PA for them when they played an early gig at Los Angeles City College. Along with Joe I was friendly with Dorothy—super voice— Mike Agnello, Craig Woodson… bloody hell—I can’t recall the other two—bass and violin. Sorry. Joe’s songs were aces. I was at their first show in a club—the Magic Mushroom, in the Valley. They were about to make their first LP with CBS when I last saw them—with Moby Grape’s producer. Can’t remember his name either. Oh well. It was fun knowing them.

What were the circumstances surrounding your second album ‘Coconut Hotel,’ which the label decided to drop due to “lack of commercial potential”. The album was released in 1995 and it’s a fascinating collage of abstract ideas. Listening today, what are some memories that run through your mind hearing it again?

The label didn’t decide anything. That music got us invited to the festival in Berkeley. It was the penultimate step before making sounds that raised the question: is that music? The label never really heard it. Lelan Rogers—our producer on the ‘The Parable of Arable Land’—and Billy Jo Dillard, one of the lawyers who owned the label, sat on the grass out in front of the studio while we recorded. It’s our riposte, in a way, to what everyone else was doing. From the start we thought of putting paid to everything. Ideas were consumed in the making. We were making gestures after which there would be nothing left to do but quit, or repeat—go thematic—idiomatic—rehash—play kitsch and or camp it up—provide plentitude—all nice of course—entertainment. We understood that people like music. We, too, of course. ‘Coconut Hotel’ was recorded at Walt Andrus’ studio—where we made ‘The Parable of Arable Land’. We worked on it with him and with Frank Davis, dear people. We recorded stereo, everything live, no overdubs. We had some plans and improvised on them. We knew it was likely unlike anything else going on. A bit mad-science perhaps, but in a good way I think, not meant unfriendly. It’s finally out on Drag City Records.

Roky Erickson played on your first album. He plays keyboard on ‘Hurricane’ and harmonica on ‘Transparent Radiation’. How did that come about? And speaking of ‘Hurricane Fighter Plane,’ I can’t get that track from my mind since I first heard it many years ago. What’s the backstory to it?

Roky Erickson was Lelan Rogers’ idea—turned out nice. He was a gifted instrumentalist and a powerhouse singer. Lelan brought him to the studio one night—him and Tommy Hall, The 13th Floor Elevators jug player. Roky listened and understood right off. He overdubbed his parts in no time. Steve knew him and the other Elevators from working as John Ike’s drum roady. Rick and I had never met him or any of them. I think he had fun. He wrote me a letter later—addressed to “Juno”—for the label to give me—they told me about it but never delivered it. I don’t know why not. Maybe it had something to do with the Elevators being in trouble with the law. As for ‘Hurricane’ I hope you don’t mind terribly having it stuck up there? Steve and I put together the music one night but never had proper lyrics until we got in the studio. The idea had been to list the names of aircraft—Hurricane Fighter Plane, Sikorsky helicopter; Goodyear Blimp, MIG 17; Sabre Jet, Piper Cub, like that—on and on. It didn’t work. I improvised what you hear live, on the fly. The ‘War Sucks’ lyrics had never been properly sorted either. I improvised them as well —after Lelan suggested dropping the original chord progression—a kind of standard repeating ascending rocky sort of thing, he said to play what he called “that jungle thing.” “That jungle thing” was a jam in E that owed something to raga. It was a descendent of what we called “free pieces”—where we’d play whatever in no key in particular.

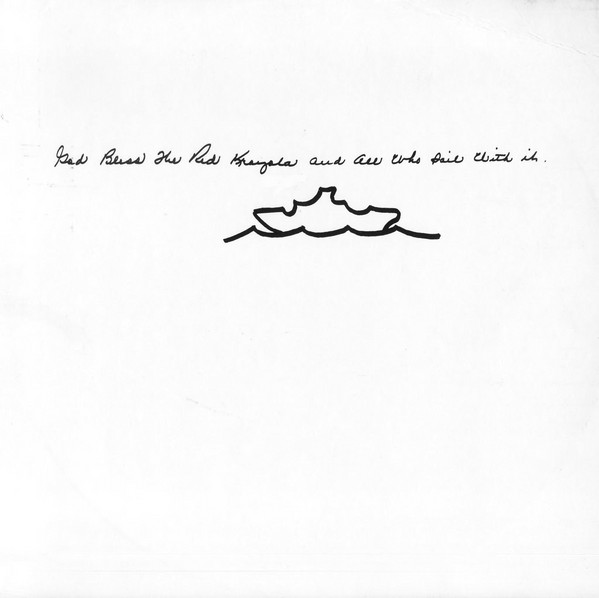

What about ‘God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It’? Tell us about its creation. Did International Artists ask you to make another one after dropping ‘Coconut Hotel’? How did you feel at the time?

The band was dead but ‘The Parable Of Arable Land’ LP made money. Lelan Rogers told me it’s an evergreen—meaning it will always make money. That it had done business got the label thinking it would be nice to have a follow-up. We parted company with them after Berkeley. I was living in Venice, in that place I mentioned sharing part of with Joe Byrd and his band. The things I was working on weren’t looking like coming together anyway. So, when they got in touch I thought, why not, and went back to Houston. I got in touch with Steve Cunningham —Rick [Barthelme] had moved to New York. By then Lelan had been fired and the label had acquired a studio—where Sir Douglas Quintet recorded ‘She’s About A Mover’. We worked there with Jim Duff engineering—producing ourselves. The label gave us a free hand. Some of the stuff was written, some made up in the studio. We developed songs and “pieces” in a variety of forms. There was no pressure from the label. It’s a set of singular pieces meant to be heard as a kind of whole. When it came out we got a call from a DJ at the radio station that had run the battle of the bands I mentioned. He wanted us to do things for him to use, funny slugs to break up his show. We declined—stupidly. It didn’t do business, though the label liked it. It is a funny enough record.

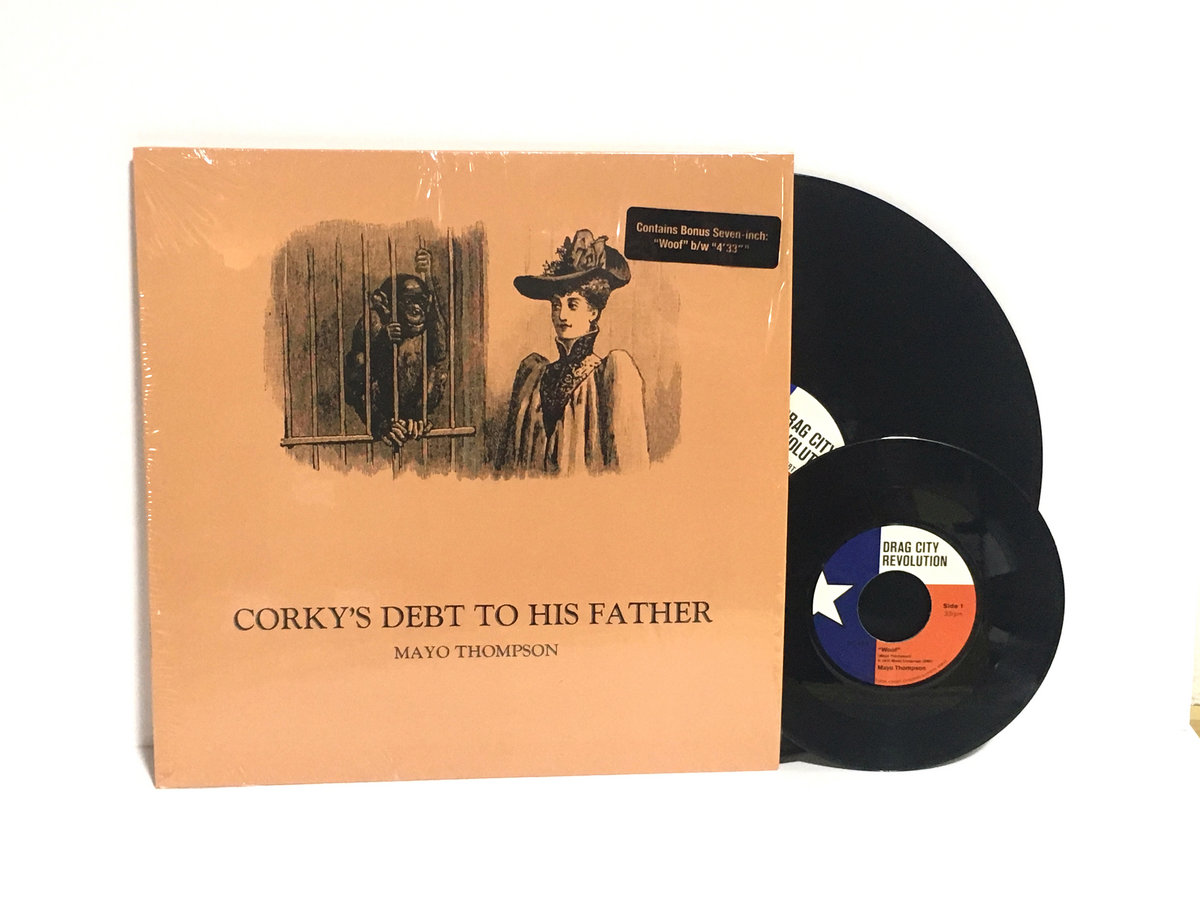

What led you to start working on your solo album, ‘Corky’s Debt To His Father’? The lyrics seem to be more intimate, more personal if you like. Who all was part of the record?

For who wrote, who produced, who played, please consult the credits. Personal—yes. It’s a solo album—unlike in the Crayola, where “I” is tropic. On ‘Corky’s Debt To His Father’ “I” is not meant indexically. After ‘God Bless The Red Krayola And All Who Sail With It’ tanked I left the label again, having decided to try my hand without a band. Again Frank Davis and Walt Andrus figure, and Roger “Rock” Romano, one of Houston’s most accomplished and versatile players. Rock and I knew each other from college. He was working at Walt’s. He, Frank and I drafted players from different bands—all dab hands. We took our time —working not every day. It gave us time to think. It took three months. Walt had started a label—Texas Revolution—and ‘Corky’s Debt To His Father’ was to be the first product.

Walt’s partners hated it. That wasn’t an uncommon reaction. A friend living in a commune told me how he would get stuff thrown at him if he tried to put it on. As Joe Dugan said, “Mayo’s voice is an acquired taste.” Only some hundreds were pressed. Some sold via mail orders. No release. It sat on the shelf until Dave Barker released it in England in the ‘80s. Drag City has released it here. These days The Corky Band and I perform the songs occasionally. Appreciation has appreciated over time.

Tell us about your involvement in art and politics in the 70s and what led you to go to England? Would love it if you could elaborate on your involvement with Art & Language.

Phew. This will take a bit. I moved from Houston to New York in ’71. On the music front I got to know Philip Glass a bit and some of the players in his ensemble. I reconnected with Manos Hadjidakis—the composer of ‘Never on Sunday,’ among other things. I had gotten to know him in ’69. He was a fan of ‘God Bless The Red Krayola And All Who Sail With It’. He had ideas about working with him on a rock musical. When he heard ‘Corky’s Debt To His Father,’ he proposed that he and I make a record together in Greece. I wrote a set of new songs and in the summer of ’73 traveled to Athens. The social atmosphere was edgy, unpleasantly charged—the Colonels junta had seized power. They were trying to get Manos to be culture minister. He somehow managed to avoid being compromised—he was friendly with Caramanlis, who became Prime Minister when the Junta fell. I don’t know. In any case, he was busy, flying back and forth to Beirut, where he was directing a festival, so, ever tired. He also had a health issue that further slowed things down. I sat there for a month and some, waiting, playing tourist, doing nothing effectively. He introduced me to his mother. I saw the flat he got in exchange for the rights to his famous tune, and the Oscar he won for it. Finally, it looked like we were never going to get to it. I gave up and started home. On the way, I stopped in Paris where I met Bob Rauschenberg—the very artist I had intended to write about in university, working toward a degree in Art History I never finished. He was in town for a show of his Untitled Press works at Ileana Sonnabend’s gallery, and another exhibition kicking off the Paris season for which Mrs. Sonnabend was responsible. I wound up working for him when we got back to New York. That lasted until sometime in ’75 when we fell out over politics. We were in Mestre—a suburb of Venice on terra firma—talking to some city officials—the mayor, a Communist, and the town planner, a Socialist. A misunderstanding arose over risk for him as an artist v risk for a truck driver. I sided with the truck driver. I was working with A&L UK by that time. In ’72 Michael Baldwin and Philip Pilkington from A&L UK traveled to New York for a meeting with the A&L NY group. I had met them then. A&L UK were unhappy about what they regarded as career-driven blurting on the part of some players in NY. NY generally were unhappy, and sensitive, feeling the UK were telling them what not to do. They had started publishing a journal—The Fox—as a vehicle in part to counter to Art-Language, the journal UK had been publishing since ’69, and in which they could be quite critical of NY in a field at a time where authorship, and authenticity, and exactly who-did-what-first counted heavily. By ’76 the UK/NY conflict was still on, and at an impasse. The UK was looking for a way to break the ice. The NY group were effectively in disarray—factions fighting over practically everything. Through scheming I shall skip over the nuances of here, around that time I got involved in NY too, and got to know Mel Ramsden and Ian Burn, whom I had met at parties before but never talked with. They were the core of A&L in New York—before it became A&L NY—party to the A&L conversation started in the late ‘60s. We started working together. Music played a role. We made the 9 Gross & Conspicuous Errors video with harangues by Mel, attacking self-image, language management, public-relations life—implicitly, others in A&L NY. Artists were thought the worst of all political allies. Factional conflicts intensified. Before long they came to a head, following a series of meetings where what was referred to as the ‘lumpenheadache’ was aired. The upshot was that factionalism and opportunism in A&L NY was sorted. The solution was an idea of Mel’s—provisions. Among those who accepted them it was agreed that all work under the A&L rubric would be struggled over, and presented as by (Provisional) Art & Language —A&L (P). A coalition formed. The UK joined in. Trans-Atlantic peace broke out. Those who couldn’t accept the provisions effectively became a kind of rump and soon went their separate ways. If you’re interested, there’s a film by Zoran Popovich—Struggle in New York—for which (P) made ‘and now for something completely different’—a segment that reflects what was going on, and what we were thinking. Soon after that (P) published an Art-Language journal that appropriated The Fox—NY’s counter publication, and Mel and his family moved back to the UK. I soon followed. The mild irony is that when I got there I fell out with Michael over something we have since settled, happily. We continue working together to this day. One last bit about politics as such—when the Vietnam War ended members of activist groups in New York such the Artworkers Coalition and others called for a group to form to promote changes in institutions that excluded women and minority artists—

Artists Meeting for Cultural Change. Some of us involved in A&L NY took part. One action was picketing the Whitney Museum of American Art on the day of the opening of that year’s Biennial. As we marched, some people nobody knew showed up and joined in. They let it be known that they were starting a new organization—the Anti-imperialist Cultural Union—and scouting for anybody interested in struggle along those lines. It was an idea of Amiri and Mina Baraka’s, an offshoot of their main deal, the Congress of African Peoples, by then a Marxist-Leninist organization, working towards forming a party following Mao. In general I shared the political aims, but their devotion to Mao Zedong, thought felt like religion. I couldn’t commit to it, or share their conviction that Mao was the only right-thinking thinker in the game. I still thought highly of Lenin, and being a war baby, still had some time for Stalin, which lasted until I realized what sort of monster he was. I also found Trotsky interesting but—per “The Mistakes of Trotsky”— found him a sad figure, never knowing when to say, “when,” finally getting liquidated.

“Punk made sense to me, and it was a life-saver”

How did you enjoy the punk scene that was happening at the end of the 70s? It was kinda a natural reaction to the events happening at the time, wasn’t it?

Punk made sense to me, and it was a life-saver. Some people in England knew ‘The Parable Of Arable Land’ LP. We were able to work.

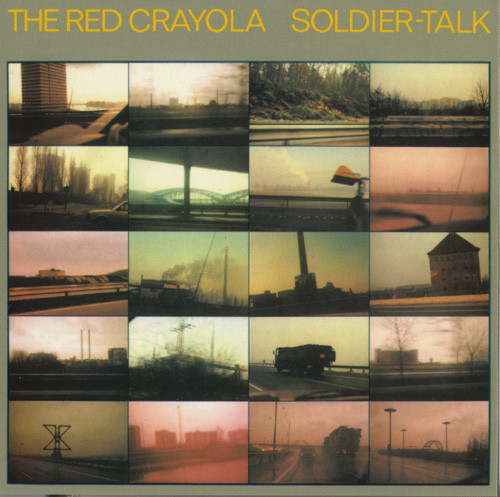

How did you enjoy working with Rough Trade Records and what eventually triggered the restart of the project which resulted in ‘Soldier-Talk’?

‘Soldier-Talk’ was made for Radar Records— Andrew Lauder’s label. I heard he had acquired the rights to the International Artists catalog and contacted him. The timing was ideal. We made a deal. Radar re-released ‘The Parable Of Arable Land’ and ‘God Bless the Red Krayola and All Who Sail With It,’ and he put us in the studio. We made a single ‘Wives in Orbit’/‘Yik-Yak’, and finally ‘Soldier-Talk’ for him. Geoff Travis co-produced. We toured it, in the UK and in Europe, with Scritti Politti opening. It did some business, and was licensed in Canada and France. Unfortunately, it didn’t do enough business in the UK. We parted with Radar and moved the act to Rough Trade, taking our last recording with us—‘Microchips and Fish’. It became the first Rough Trade 12”. Working there was fun.

I recently interviewed Gina Birch of The Raincoats, which you worked with as well. Was it fun?

I think of Gina Birch as my soul-sister. The Raincoats are a fairytale in a supermarket—o’clock, o’clock.

In a recent interview with Pere Ubu’s David Thomas, he said “My ambition for Pere Ubu was to be discovered in a used record bin in 30 years”. How did you enjoy being a member of the band? You brought a series of new ideas and techniques to the band.

There were aspects of playing in that band that were cool. I knew them before joining. In the early days with Radar Records, Jesse Chamberlain and I opened for them in England and in Europe, and they all played on one or the other track on ‘Soldier-Talk’. I think they thought the Crayola made interesting music. When they invited me to join I was thrilled—they operated at a much higher level than I’d ever managed, had a great manager—Cliff Bernstein—and were busy. We recorded two LPs and a single for Rough Trade. None of them did great business unfortunately. We fell out making the second one—’Song of the Bailing Man’.

How did ‘Ludwig’s Law’ come about?

In ’87 I moved to Germany where I reorganized the band yet again and tried to get a deal, all to no avail. We did some recording at Conny Plank’s studio. ‘Ludwig’s Law’ happened because Conny and Dieter Moebius had been making a record a year together for ten years and wanted something fresh for a new one. All their earlier ones were instrumental. They asked me to write lyrics and sing. I joined in but when I thought of singing, I had no lyric ideas. Luckily, hanging about in the art scene I had met Albert Oehlen and Werner Buettner. They had written a book I found hilarious fun—Angst vor Nice. I gave up thinking about singing and instead read from their book—in the spirit of “An Harangue” on Corrected Slogans. Conny and Moebius’ label hated it. They wound up ditching the vocals. The version with me reading was finally put out by Drag City Records. It’s funny, I think. I recommend reading the book though, if you can find a copy. It may not be easy but would be worth it.

Drag City issued Art, Mystery and After Math books, how did you first get interested in writing and in comparison to music, what’s your creative process like?

Process? Quite similar to writing music— starting somewhere—trying to take it somewhere —further—beyond—getting back—reading and rereading—reworking—ruthless editing—having fun with language. I’ve written since high school. It has always been just something I do. Nowadays, I am fortunate in having an understanding association with Drag City Books, who happily find some of what I scribble amusing. We’ll see if anybody else does.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

As ever, for a chance to chat like this, and just so—thank you, and best wishes.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Mayo Thompson (circa 1980) | Courtesy of Drag City

Drag City Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / SoundCloud