Raven | Interview | Unveiling Raven: The Resurgence of a Decades-Long Mystery

Raven is a band whose legacy has remained veiled in mystery for decades. Blending hard rock with acoustic ballads, Raven recorded an unreleased album in 1973, now brought to light thanks to the Bright Carvings Records.

This recording serves as a relic from a bygone era, providing insight into Raven’s world of sonic experimentation. With the release of this previously unheard material, Raven’s music emerges anew, captivating audiences with its raw energy and timeless, inventive guitar work. Comprising entirely original compositions, it’s a delight for aficionados of the Dandelion Label, obscure Decca, Harvest, and Deram albums, among others.

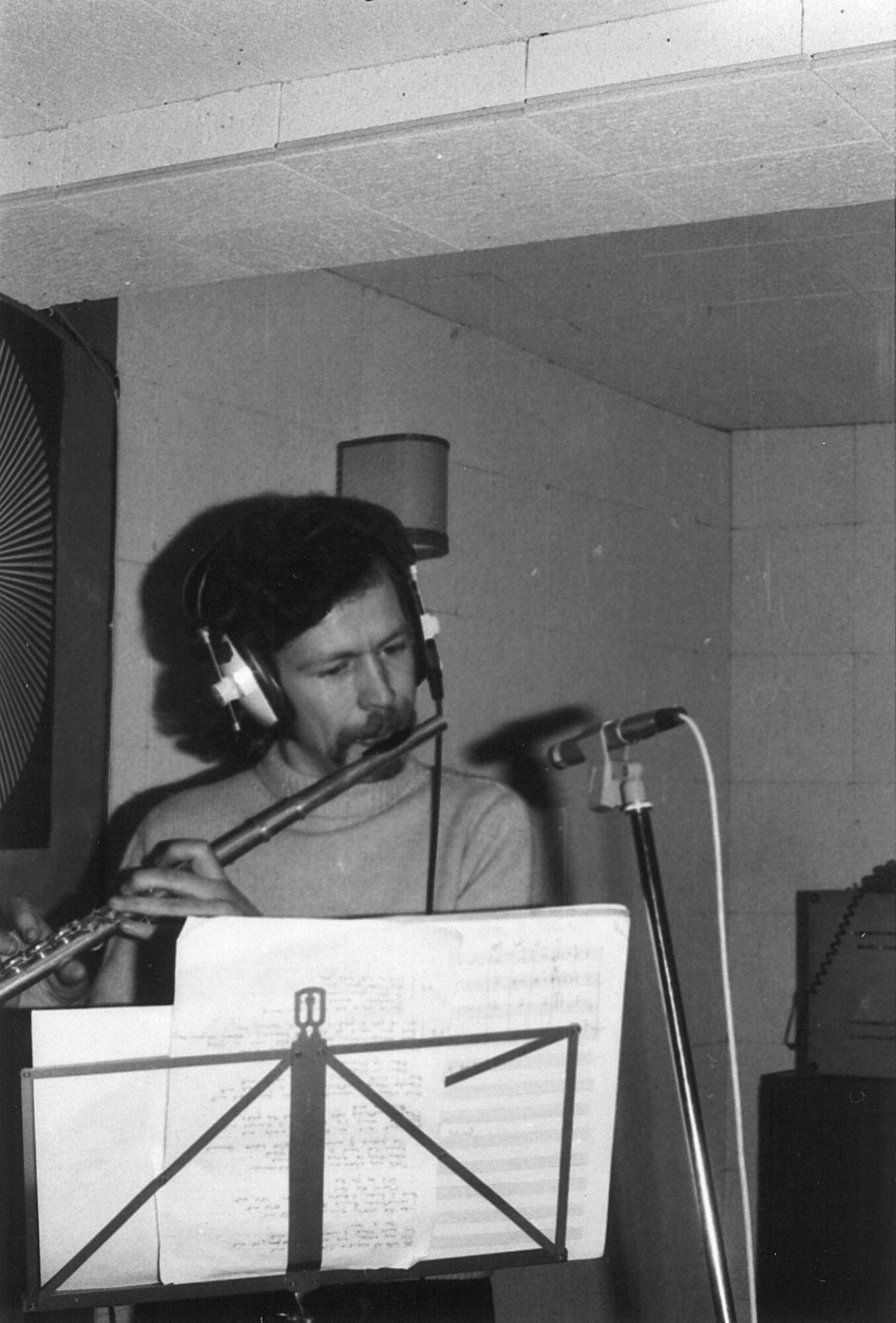

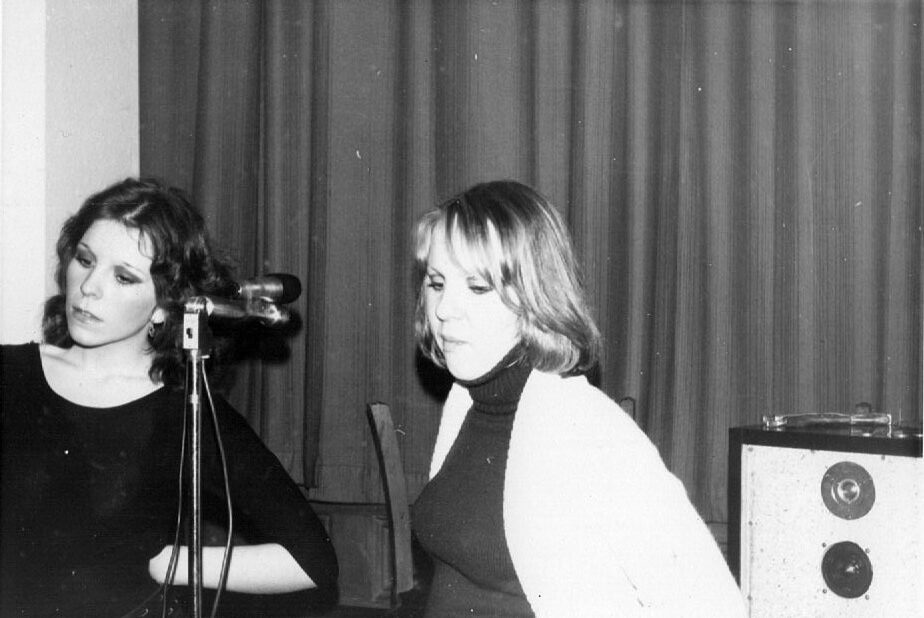

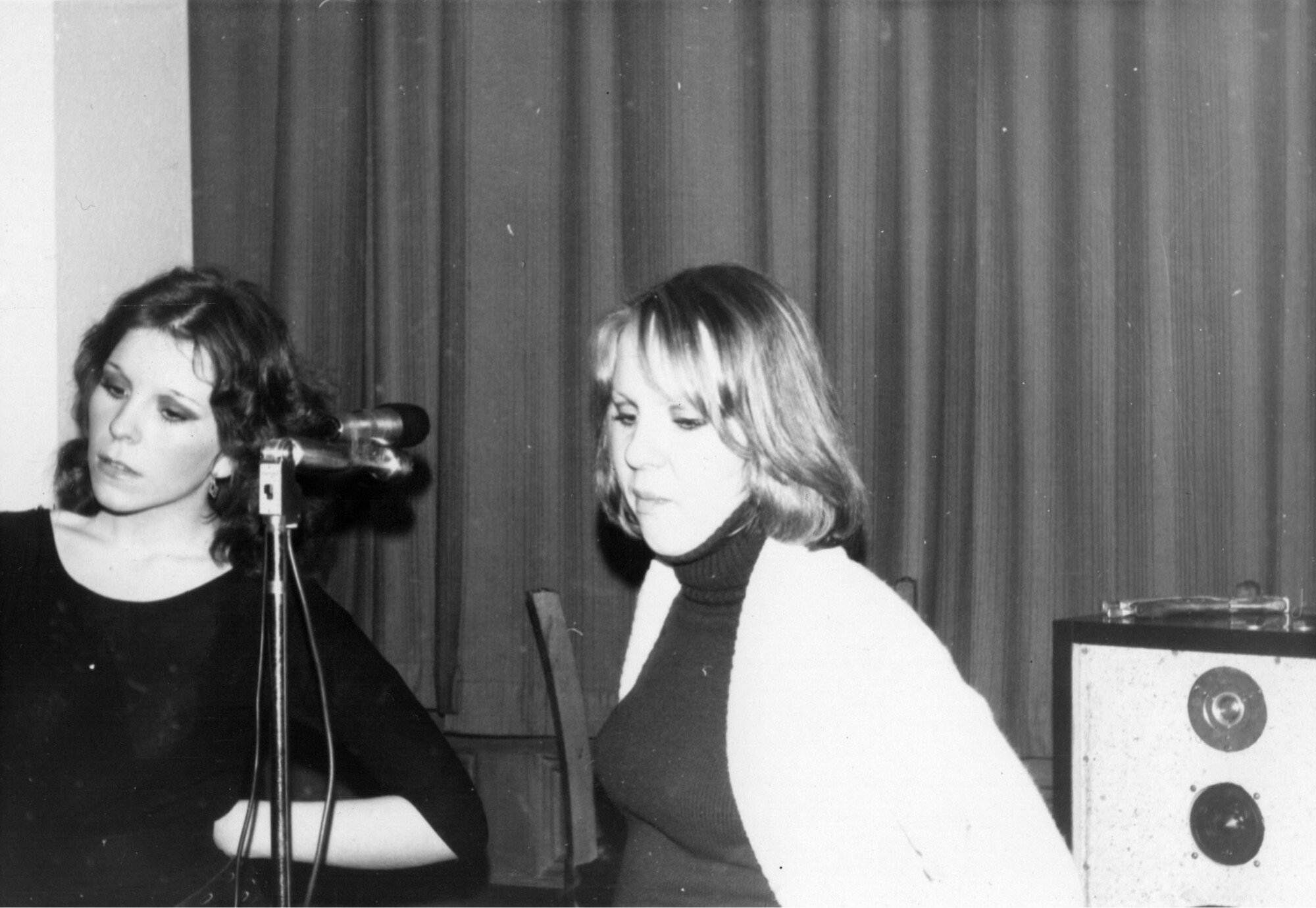

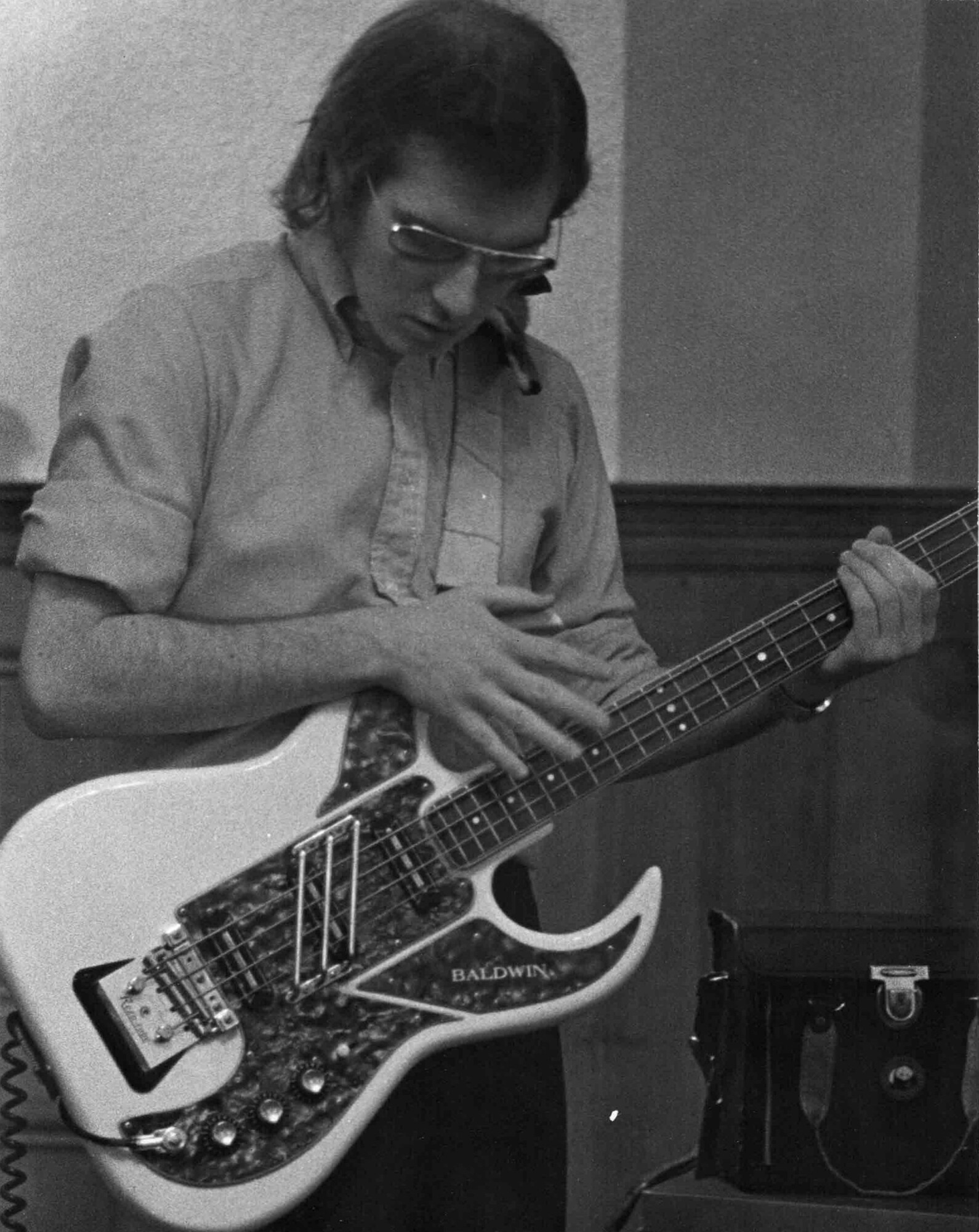

The band consisted of Barry Ruffell (guitar, lead vocals, piano, brass), Andy Franks (guitar, backing vocals), Frank Holland (guest lead guitar), Ozzie Garvey (drums), Roger Cloake (bass guitar, backing vocals), Malcolm Perry (flute), with backing vocals by Diane Hudson and Vanessa. The engineer was Dave Ruffell.

“A combination of folk music and west-coast rock bands”

Would you like to tell us where you were born and what could you say about your upbringing?

Barry Ruffell: I was one of the post-war “baby-boom” generation, born in Brighton, UK, in 1948. My earliest memories are of the family (parents, older brother, and myself) living in part of a big old Manor house in Lancing, owned by the local Council at that time, and where my father was the resident caretaker. It was almost like a village community – the pre-school nursery was in the same building, friends and relatives lived nearby, and the primary school was just across the park – in which my early childhood went on in a safe, familiar, and supportive environment (despite the inevitable sibling rivalry with the older brother).

What did your parents do and when did you first get interested in music?

In 1948, my father ended 23 years’ service in the Navy, and a series of occupations followed – caretaker at first, employee in a railway carriage works, painter, decorator, and shopfitter, and, with my mother for a period in the 1960s, running a small café and cake shop.

My mother had met and married my father during the war when she had been a Wren (in the WRNS – Women’s Navy). She was mostly a homemaker but worked as a part-time school dinner lady for a while and later had jobs in shops.

I was interested in music since before I can remember – mostly through my dad’s collection of 78 rpm records. Nat King Cole, Ella Fitzgerald, Nellie Lutcher, Fats Waller, and a few classical piano pieces… I remember precisely the excitement I felt, aged about 6, when my mother asked if I wanted piano lessons – an offer I leapt at. My teacher, a Miss Winifred Doggett, was an elderly unmarried lady in Lancing, who took me reasonably successfully through the elementary stage but who, regrettably, was not one to inspire the enthusiasm of a child, so the piano tuition dropped away by the time I was 10 or 11.

Do you recall a certain profound moment when you knew you wanted to become a musician for the rest of your life?

There was no specific epiphany – more an aspect of life that I grew into, since music had been present since the beginning. It was always part of the narrative that music was encouraged but not to be regarded as a reliable career. The background to this was that my mother’s father had been a professional violinist, after coming out of a military band in the early 20th century. He had played in theatre orchestras – which were thrown out of work in the late ‘20s when “talkies” became popular, and thereafter found it very hard to make a living, eventually going to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) to work, where he died, separated from his family, in 1944. This had colored my mother’s understanding of the perils of an insecure livelihood, and I was actively discouraged from contemplating a professional musical training – even if I had had the aptitude to qualify for it

What were some of the very first high school bands you were part of?

I attended a boarding school with a Naval tradition from the age of 11, where there was a marching band playing for parades and similar events. It was there that I began learning brass instruments and went on to play trombone (both valve and slide), euphonium, and cornet.

In my later school years, I became enamored with traditional jazz, blues, and folk music. These were the years of the “trad revival” (with artists like Chris Barber, Acker Bilk, Kenny Ball, among others), and of course, the LPs of Joan Baez and Bob Dylan’s ‘Freewheelin’ in 1963. In my final year there, a few of us put together a would-be jazz band – The Rev. B Ruffell and his Righteous Congregation. (I borrowed a dog-collar from the school chaplain for stage attire). I also played mandolin in a folk ensemble, performing mostly popular Americana material as I recall.

After school, I attended Sussex University (1966 – 69), which had an active Folk Club. This was the height of the folk revival in the UK, and folk clubs were abundant, providing a platform for performances by some remarkable and influential musicians. The Watersons, The Incredible String Band, Sandy Denny, The Young Tradition… a host of top players and singers visited Sussex, and the experience cemented my lasting engagement with the folk scene. It was there that a few of us regulars at the club produced an LP titled ‘Brothers and Sisters are Watching You,’ and I contributed to ‘Horsemusic’ – a professional recording by my friend and concertina player, Lea Nicholson.

It was in the summer of 1968 when I had my first paid gig – playing on Saturday nights in a Worthing pub. The fee was 30/-. (£1.50p in today’s money). My partner was John Mitchell (on bass), who later played tenor saxophone on the Terraplane LP.

Where did you first meet future members of Raven?

After university, and a year or so working in Liverpool, I returned to Sussex and began to connect with a group of local players – primarily through the ‘Worthing Workshop’. This was essentially a fairly disorganized gathering of young people arranging band gigs, poetry readings, and various other ‘happenings’. We chose to call it an Arts Lab, which was somewhat pretentious, but harmless enough and very enjoyable. It was the post-60s tail end of what felt like a liberated and creative era. Through this network, I met Andy Franks, Roger Cloake, and later, Ozzie Garvey.

Tell us about your involvement with Terraplane.

Terraplane was the name of a blues band that performed at Worthing Workshop gigs. It had fluctuating membership, including at one point the excellent singer and harmonica player, Gerry (later Leo) Sayer. Initially, I wasn’t involved, but I joined a temporarily reformed lineup convened by Nigel Tannahill, guitarist and original member, to seize an opportunity to record some material in a new, very simple studio created by my brother, Dave, on Hayling Island. The result was the material – all recorded in mono over the course of a single day – that was pressed into a 99-issue LP, recently reissued on the specialist Bright Carvings label. The band did not continue in that lineup, and I don’t recall us ever performing any live gigs, but the recording session was enjoyable: an eclectic mix of material and influences, very much “of its time.”

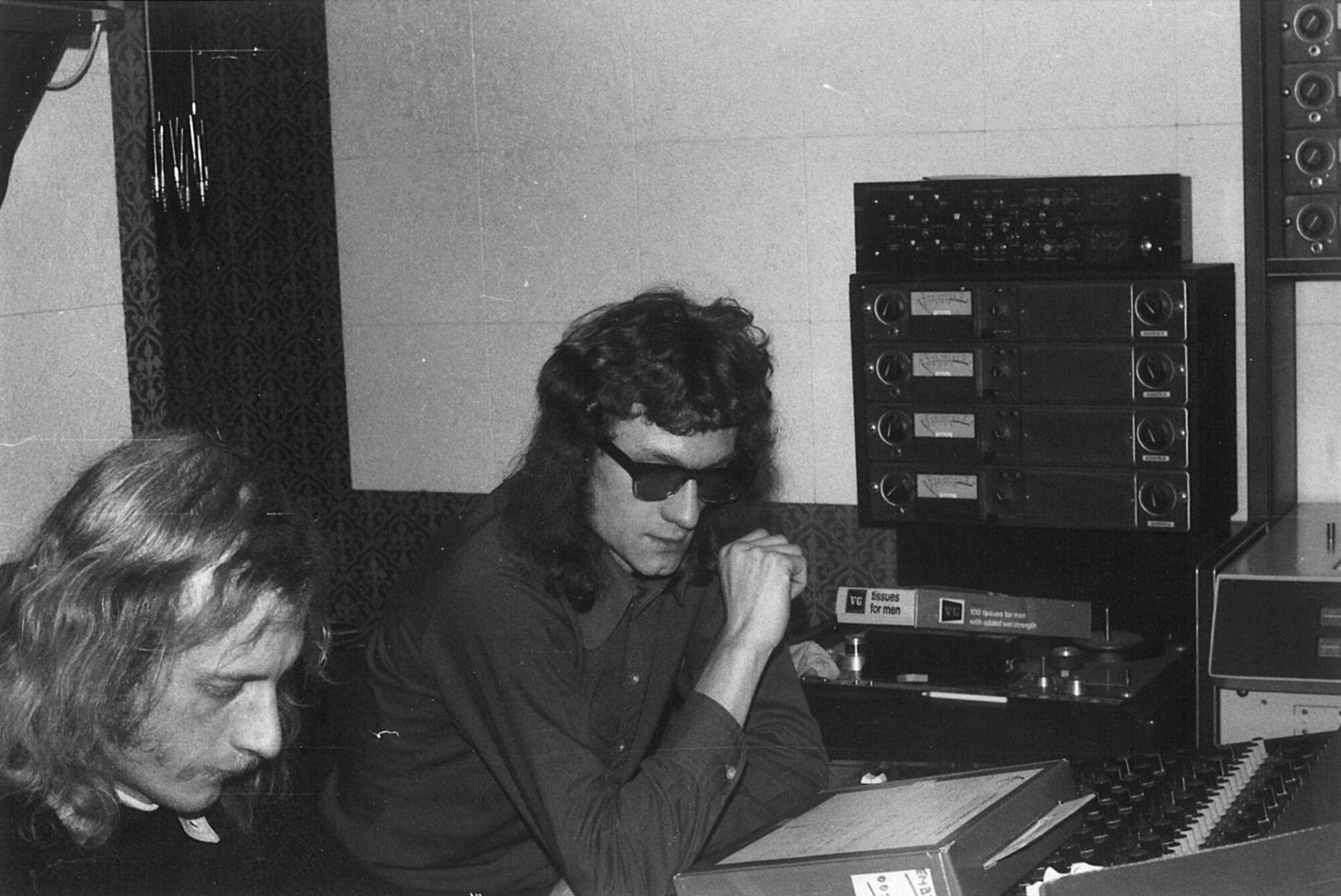

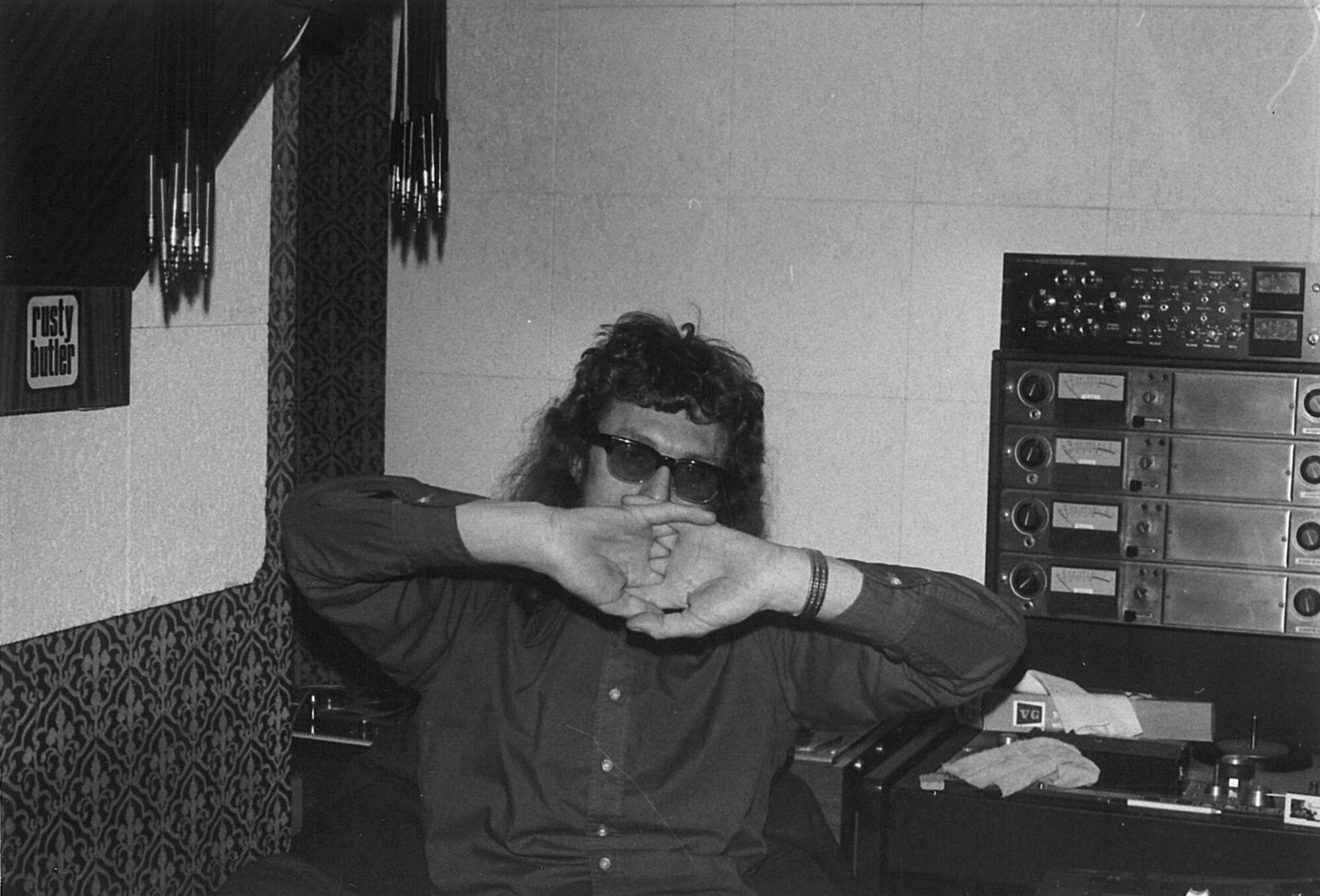

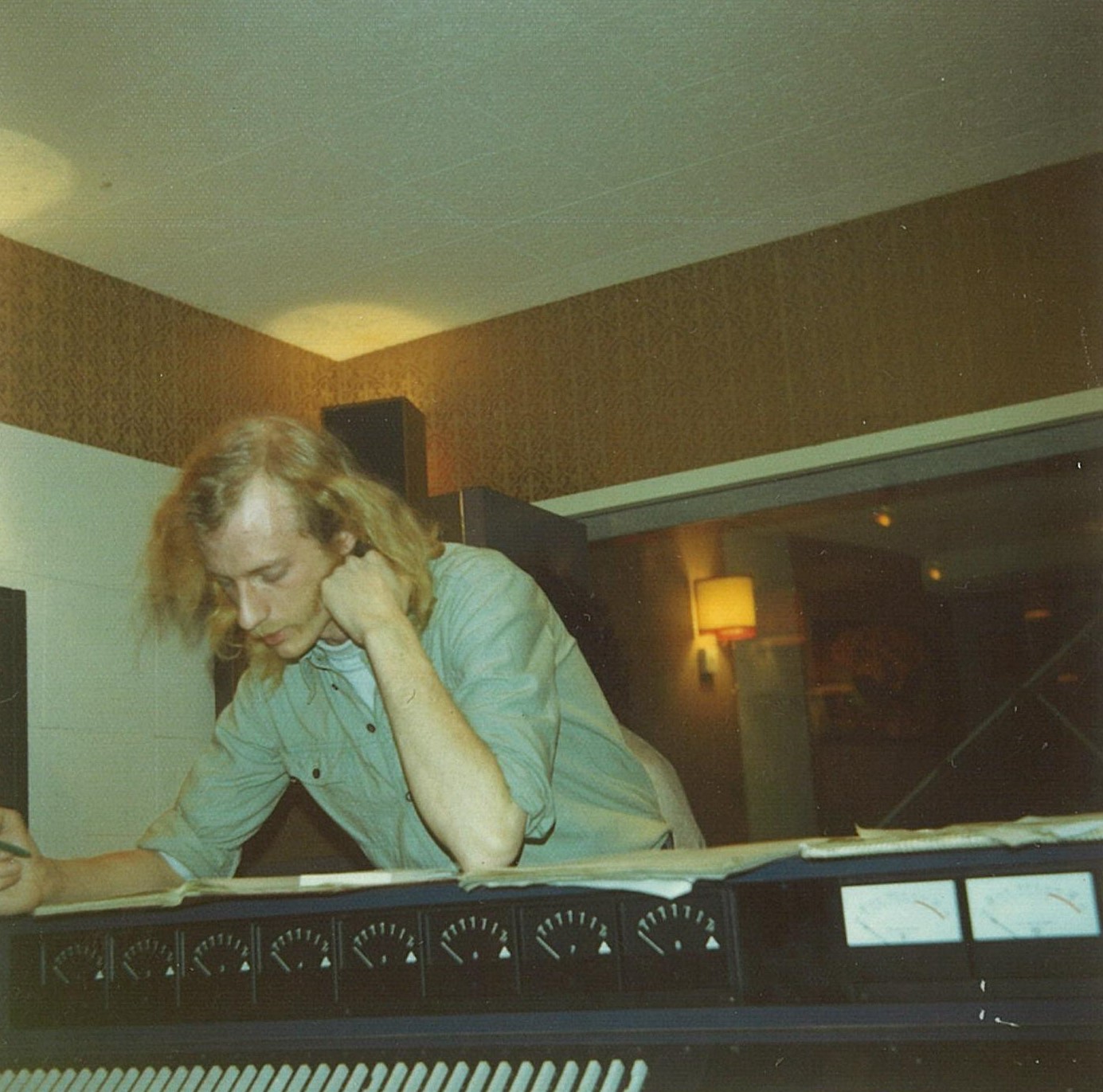

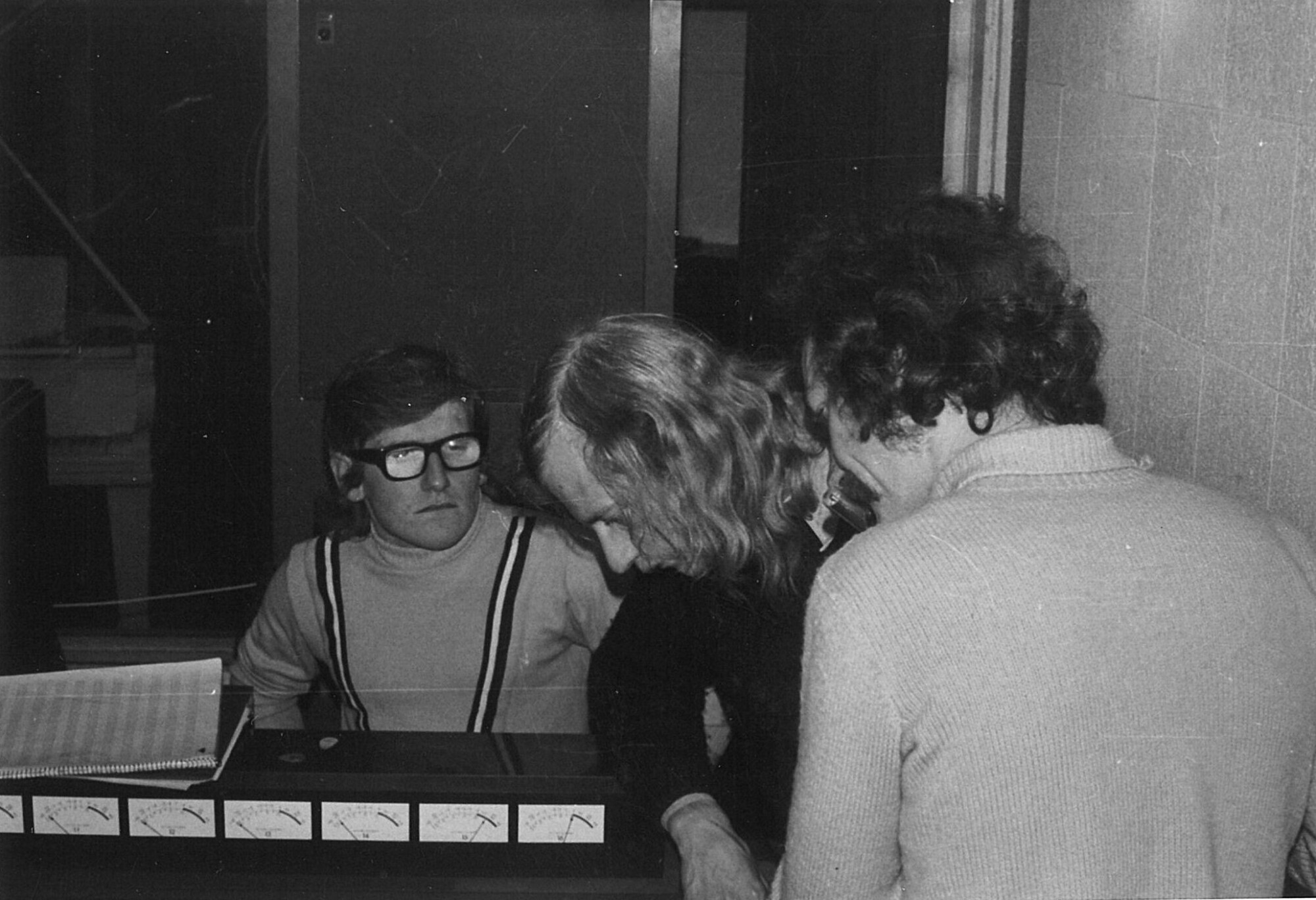

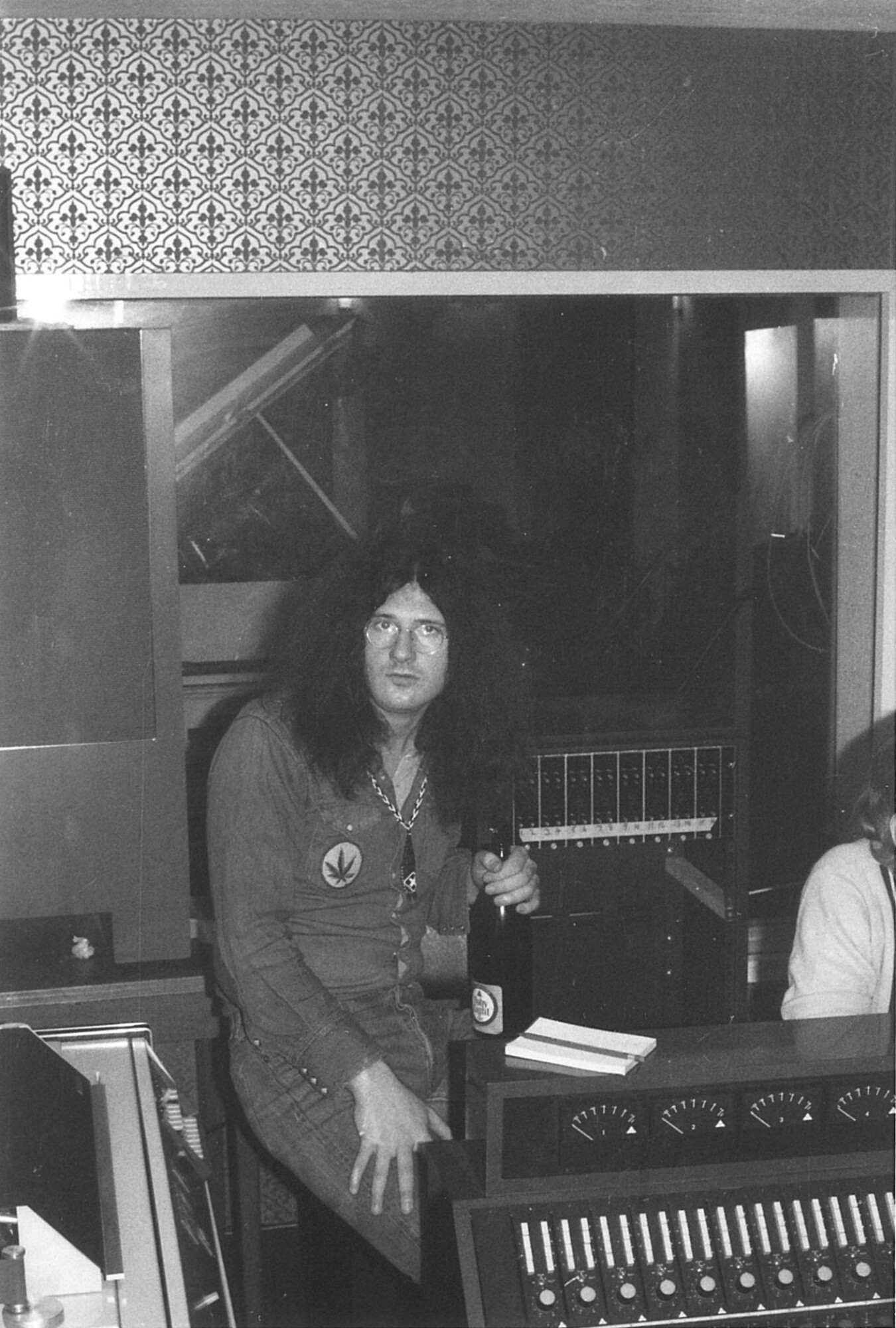

Tell us about your brother and his studio…

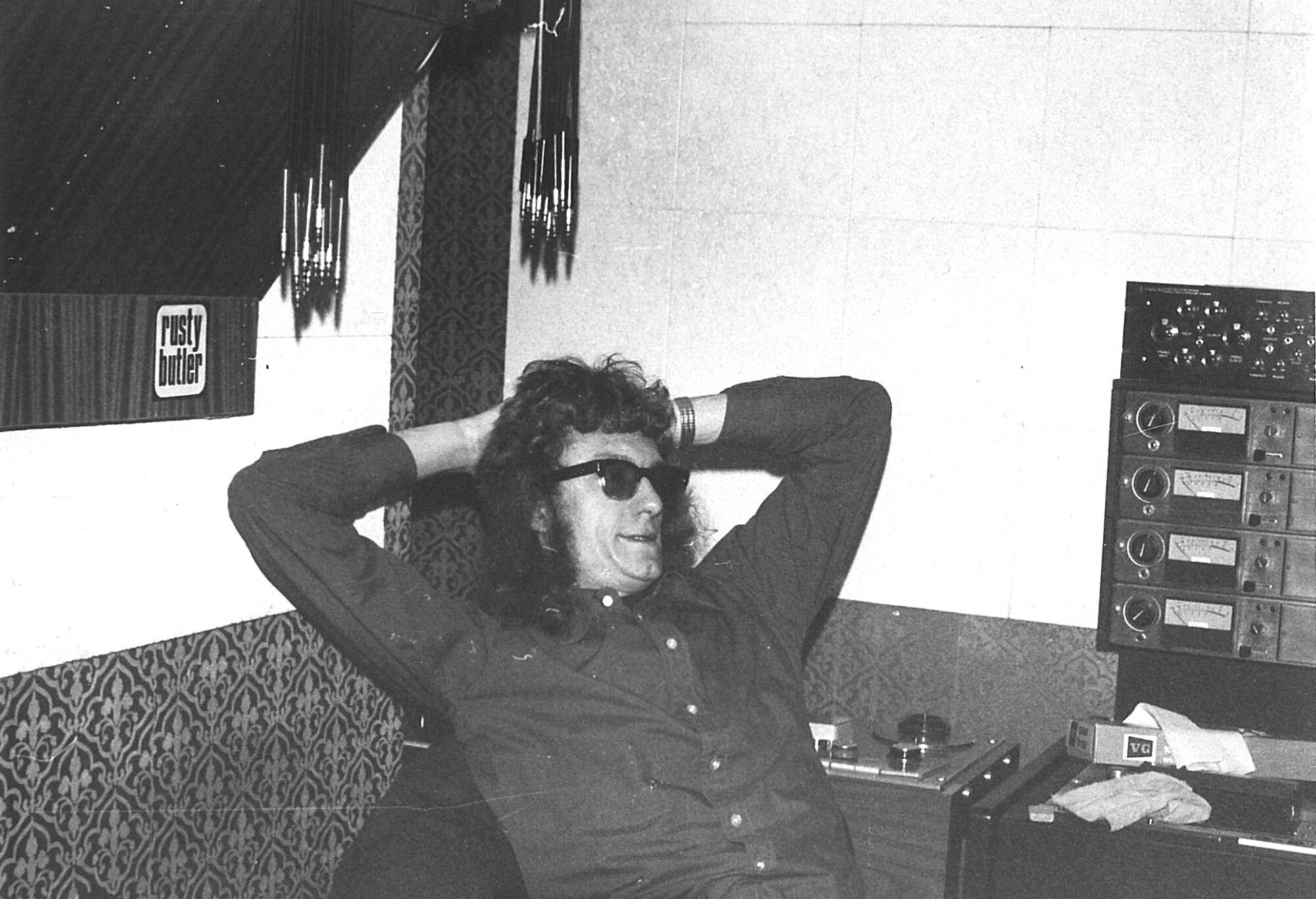

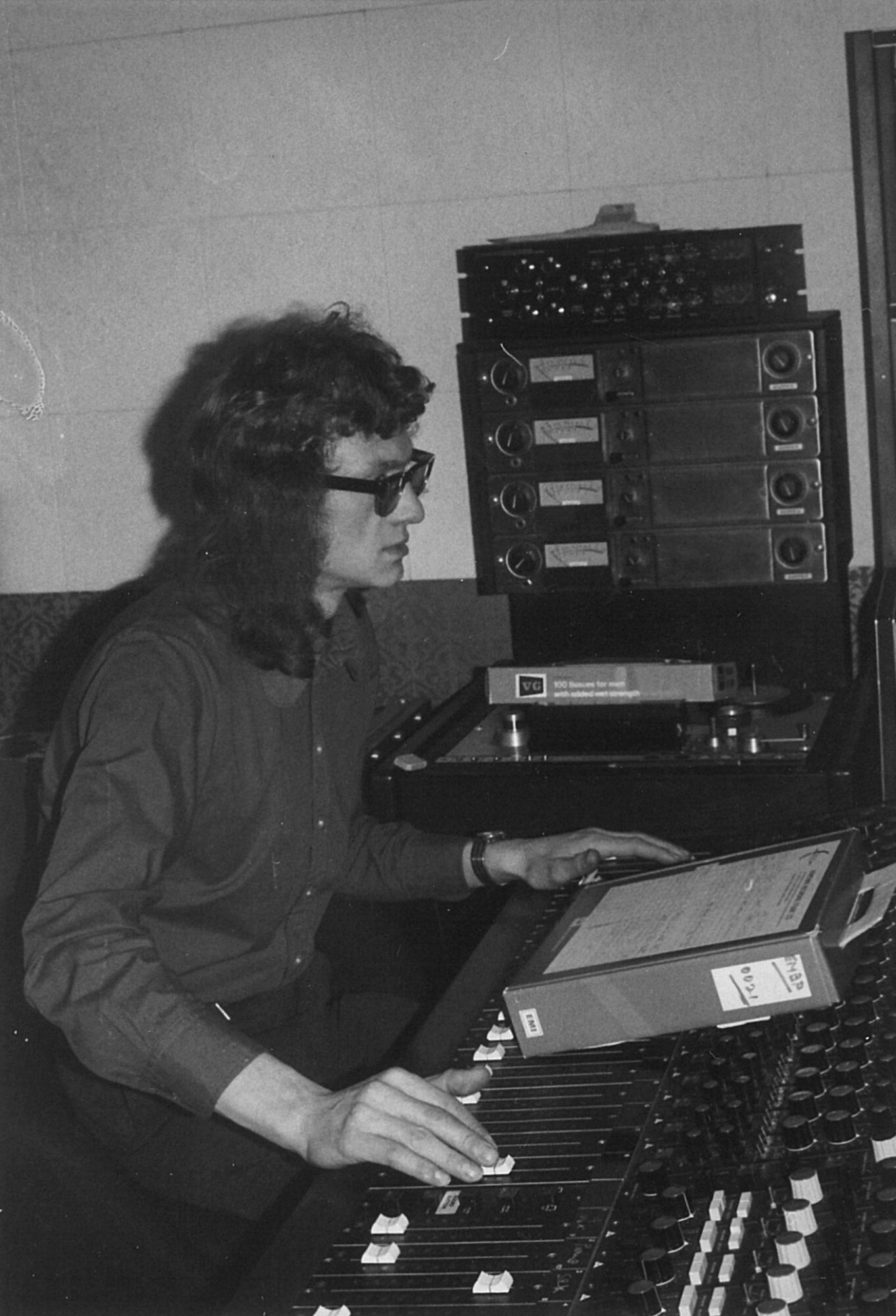

Dave, my brother, had a lasting interest in hi-fi. In later years, he ran a dealership specializing in high-end audio equipment. While operating a camera shop in Hayling Island, he embarked on his first venture into the world of recording studios. He converted an annex, lining it with egg-boxes to dampen unwanted echoes. This studio featured a two-track tape recorder and a fairly simple desk. However, it provided him with the valuable experience he needed to envision a more ambitious project.

During this time, most of the recordings he worked on were commissions for school choir performances.

How would you describe the music scene back where you lived?

In the late 1960s and early ’70s, the music scene where I lived was vibrant and easily accessible. Local bands were forming and finding venues to perform was not a challenge. Additionally, the folk music scene thrived, especially in nearby Brighton, with some excellent clubs catering to enthusiasts.

A local impresario organized events at the Assembly Rooms, our local concert hall. This venue hosted high-profile acts such as Deep Purple, Arthur Brown, The Who, and Fleetwood Mac (with Peter Green!), among others. Furthermore, nearby towns with larger venues provided additional opportunities to experience live music. Notably, I had the chance to see Frank Zappa and the Mothers, who remain my top band of all time. (I still hold dear the first twenty-five or so albums of Frank’s).

What led to the formation of Raven? What’s the story behind the band name, and who were the band members? Did the band go through any lineup changes?

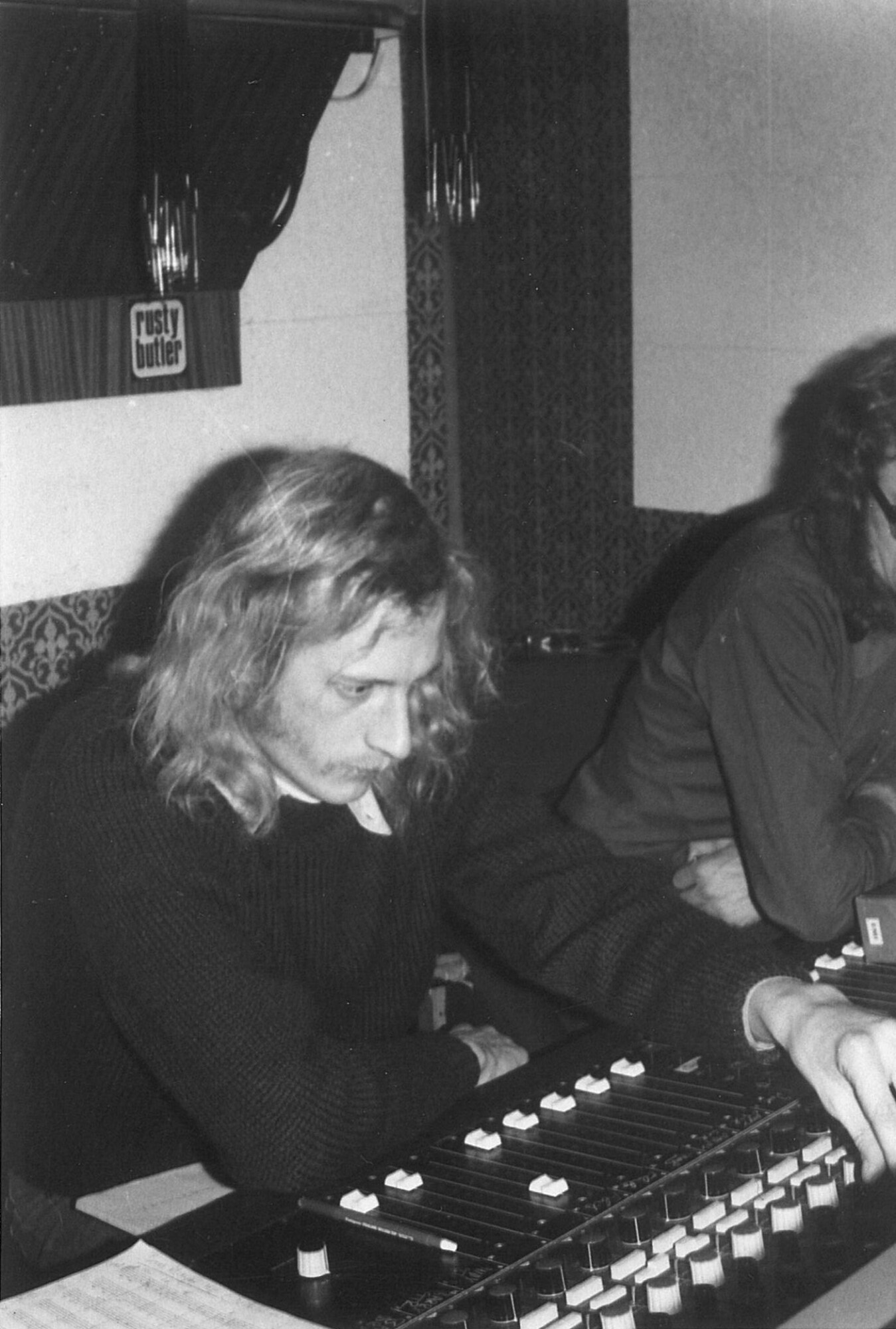

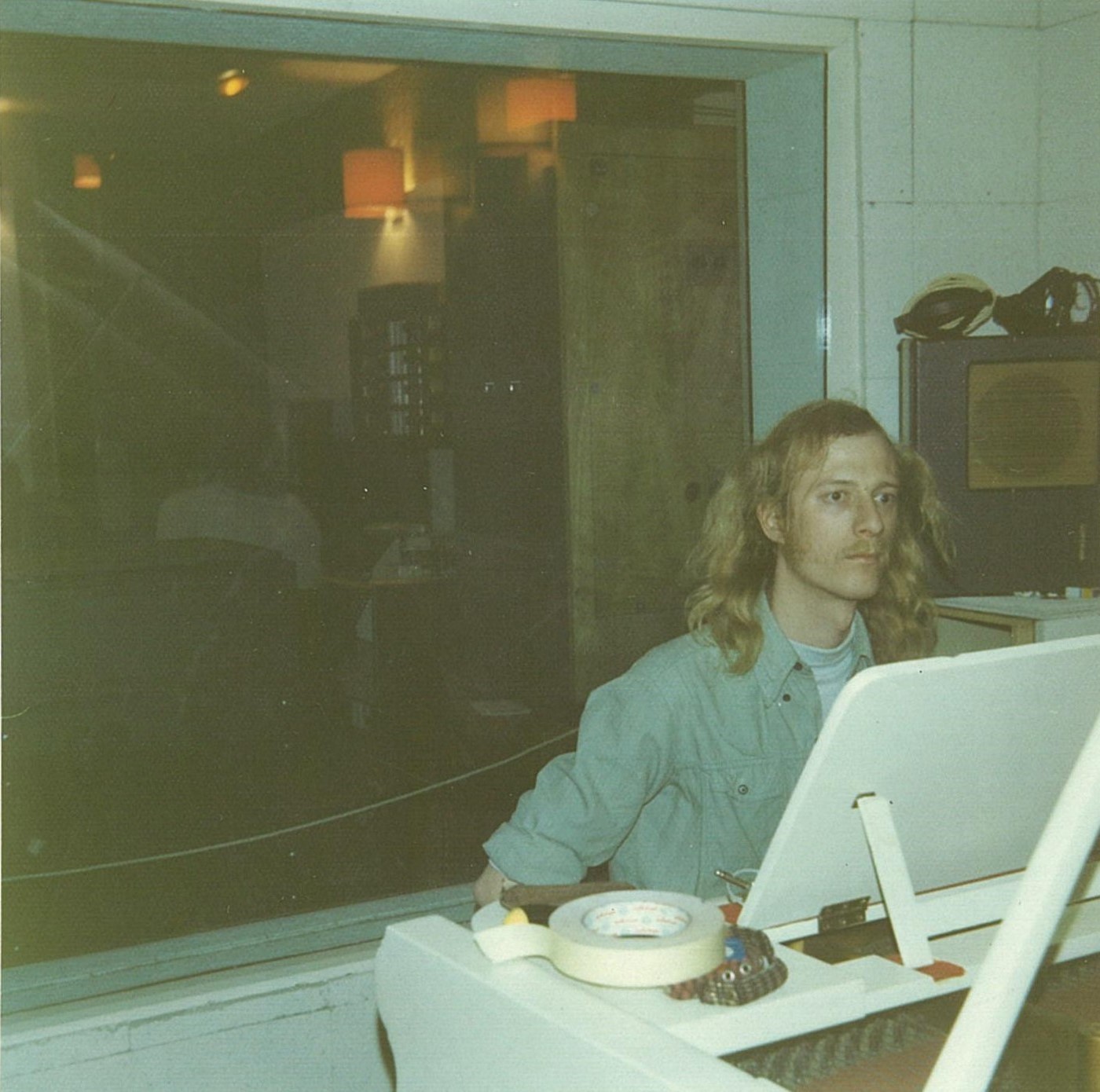

Throughout this time, I had been writing songs without really knowing what to do with them, but in 1973, my brother had developed his recording business and set up Saturn Sound studio in Worthing. With a 16-track facility, he needed a second pair of hands, and I went to work with him as a “tape-op” (i.e. tape machine operator for the 16-track recorder) (or, more grandly, “Assistant Recording Engineer”). Among the duties associated with the recording commissions for visiting bands, there was time to put down some of my own material. This was the opportunity to draw on the circle of players I knew to put a band together for the purpose. I had played for a while in a pub trio with Andy Franks (guitar) and Roger Cloake (bass), and knew Ozzie Garvey, a redoubtable drummer who had moved down south from Yorkshire. We recruited two backing singers, Vanessa (surname never known), and Diane Hudson – an art college student and daughter of a work colleague of Andy’s. We were given the run of a disused back room of a nearby pub to set up and rehearse, and meticulously prepared the material, the overdubs, the order of recording, etc. so we could use the available studio time most effectively. The on-site production decisions were mostly Dave’s, but we knew pretty well exactly what we planned to play.

How the name came about was down to whimsy. It sounded neat, and the album title (‘Traitors’ Gate’) was arrived at just because of the Tower of London association. Nothing more significant than that.

The band played a couple of local gigs, but as other demands came along, people left and the lineup had to change. Unlike a band playing covers, this meant a great deal of rehearsing in order to bring new members up to speed on totally unfamiliar material. This was demanding and tricky to arrange, and since we were doing more rehearsing than gigging, the band’s days were numbered – especially as we had tried to hawk the recording around a few people in the music business but had had no takers.

Bright Carvings issued your recordings from the 70s. How did Jon find out about those recordings? When in particular did you record it?

I don’t know how Jon found out about the first one (Terraplane) – though word of this LP had got around, as I had previously been contacted by a couple of people who wanted to buy copies when I still had some spares. I was put in touch with him through Nigel Tannahill, who I think was the first person from the band that Jon contacted. I was reluctant to have it re-issued at first because I didn’t think the material or the recording was very good, but after a couple of conversations with Jon, he persuaded me that it was the sort of recording that was of interest to collectors.

Subsequent conversations with Jon led on to his considering some other recordings of mine for re-issue: in particular, the Raven tapes and, possibly, some of the tracks from ‘Brothers and Sisters are Watching You’ (1968) by the University Of Sussex Folk Club, and maybe ‘Different Circles’ (1980) – the first LP by Uncle John’s Band – an outfit Andy, Roger, and I formed with others after Raven.

Was your album released on acetate?

No, it existed only on reel-to-reel tape and subsequent cassette and digital copies. I don’t know what happened to my brother’s stereo master mix. Ironically, for a long time, I kept the original raw recordings on 2-inch tape reels, but after years in my attic, I thought they would never be played again, so I sold them on eBay to someone with a 16-track studio who could wipe them and re-use the (expensive) tape. Of course, I wish I still had them to use for a modern remix for the Bright Carvings re-issue. But…

Please share your recollections of the sessions. What were the influences and inspirations for the songs recorded?

The sessions were carefully prepared in hours of rehearsal, so we knew in detail what we wanted to lay down, and in what order, when we were in the studio – so the actual recording process was very concentrated and quite intense. There was definitely an excitement about working that way and, despite some frustrations at times, I found it extremely enjoyable.

The songs had been written at different times over a period of three or four years. It’s difficult to pin down specific influences, but I suppose the background was a combination of folk music and west-coast rock bands. I can’t say whether that shows through to other listeners in the way this LP comes across. They were quite different from each other in mood, style, and content, and so didn’t form a coherent body of work. I think this may have been one of (possibly many) reasons why our attempts to interest record companies didn’t come to anything: it’s probably difficult to see who such an album would appeal to for commercial purposes.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

Listening back to it after all this time, I can pick out certain themes: ‘Equal Opportunity Scene,’ for example, clearly reflected my cynicism about political rhetoric in the face of obvious social deprivation. (I had been a student of Sociology and, subsequently, a Social Worker). I think ‘After The Inquest’ and ‘What If The Streets’ were attempts to indicate a view about the futility – to me at least – of holding on to religious beliefs in the current age. A couple of them – ‘Song For An Acquaintance’ and ‘Different Circles’ – are more personal reflections on loss in one form or another. Others, such as ‘Hazy Days’ and ‘Song For Little Girls,’ are not meant to suggest anything of any depth, but are attempts to play with words, themes, and fun musical ideas. ‘Down On The Table’ is fairly tasteless, and (dare I confess) ‘Guerrilla Lady’ was suggested by reading about Leila Khaled, a revolutionary activist of the time who seemed extremely attractive and quite dangerous. As a song, it’s a bit repetitive, but it did give Ozzie an opportunity for some quite dramatic drumming. Also, an early example of Dave attempting to achieve a phasing effect on vocals using a tape varispeed controller.

What happened after you were done? Did you send any tapes to radio stations or bigger labels? Did you get any airplay?

We didn’t try to get airplay, but with the help of an associate of Dave’s, Andy Cowan-Martin, who was on the fringes of the music business, we visited a handful of record company representatives and managed to get them to listen to the material. As with most local bands, there were no takers, so that was an end to any commercial aspirations. But we weren’t too disappointed: we all had day jobs and weren’t depending on the recording for anything more than the fun of completing the project.

How much gigging did you do? What are some bands you shared stages with?

Not a lot of gigging: I remember a couple that we did as stand-alone acts (i.e., not as a support band) that went pretty well – at a local high school, and at the local Art College – but changes in the lineup and the difficulty of doing enough rehearsing with new members to maintain the band meant that the input of time, effort, and expense wasn’t really sustainable.

How long did Raven remain active?

From memory, less than a year after the recording project. By the middle of 1974, we had decided not to try to fill vacant slots in the lineup but to discontinue. Anyway, another opportunity for a simpler way of life had come up.

“The satisfaction of completing the finished article as intended”

What followed for you later on? What about other members?

A friend told us that his local pub landlord was up for having some music in the bar on Sunday night: this was the Spotted Cow in Angmering Village, just outside Worthing. Andy, Roger, and I got the gig and went back to trio format, playing for modest (but regular) money and free beer. The repertoire was a familiar mixture of Americana, blues, gospel, and folk material. Other players would come and sit in, and as time went on two of them became fixtures, so by late 1976 we cohered as a five-piece, playing every Sunday night and on other odd occasions as invited. At one point someone wanted to book us for a function and asked what we were called: as we had just played Grateful Dead’s ‘Uncle John’s Band’, we seized on the name and stuck with it.

That outfit proved to be a lot more successful and locally popular, lasting with a few changes of personnel until 1999 – with a very full diary, and the opportunity to make several recordings. One of these was pressed into a 99-copy vinyl LP, ‘Different Circles,’ while the later ones were sold locally on cassette.

Of the Raven members that we know about . . . Ozzie went on to play with punk band, The Depressions. Roger moved on to play bass for another local band, which is still going, Big Yellow Taxi (Uncle John’s band’s main rivals in the area), and Diane continued her Art College studies and has become a successful artist and sculptor.

After Uncle John’s Band ended, Andy went on to play with another local trio, The Rising Sons, and a ceili outfit, The Village Band’. Regrettably, he died after a long illness in 2010. For myself, since UJB I’ve been playing with a multi-instrumental folk band called The Rude Mechanicals (www.rudemex.co.uk).

Is there any unreleased material? Maybe songs you did live but never recorded? Or some material you did with other projects later on?

There were three items from the Raven tapes that haven’t found their way onto the Bright Carvings re-issue. One, called ‘Oh, Darling!’, was a shamefully weak attempt at a maudlin doo-wop track, which didn’t deserve another airing anyway. There was one called ‘Mister Green’ (actually Dave’s favorite of all of them), the words of which were written by a friend of mine in the Liverpool days, Malcolm Forster. Finally, ‘All The Friends’ – a whimsical reflection of mine on the passage of time, which I was actually sad to lose from this collection, as it involved what I thought was a rather satisfying arrangement for the brass section. But there you go: can’t have everything.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band?

The best thing for me about Raven was the effort we all put into it in rehearsal as an ensemble, and the satisfaction of completing the finished article as intended.

If asked to revisit any of the songs in the hope of them being found worth repeating, I’d opt for ‘After The Inquest’ and ‘Different Circles’ in the slightly reworked version we used for the first UJB album.

Klemen Breznikar

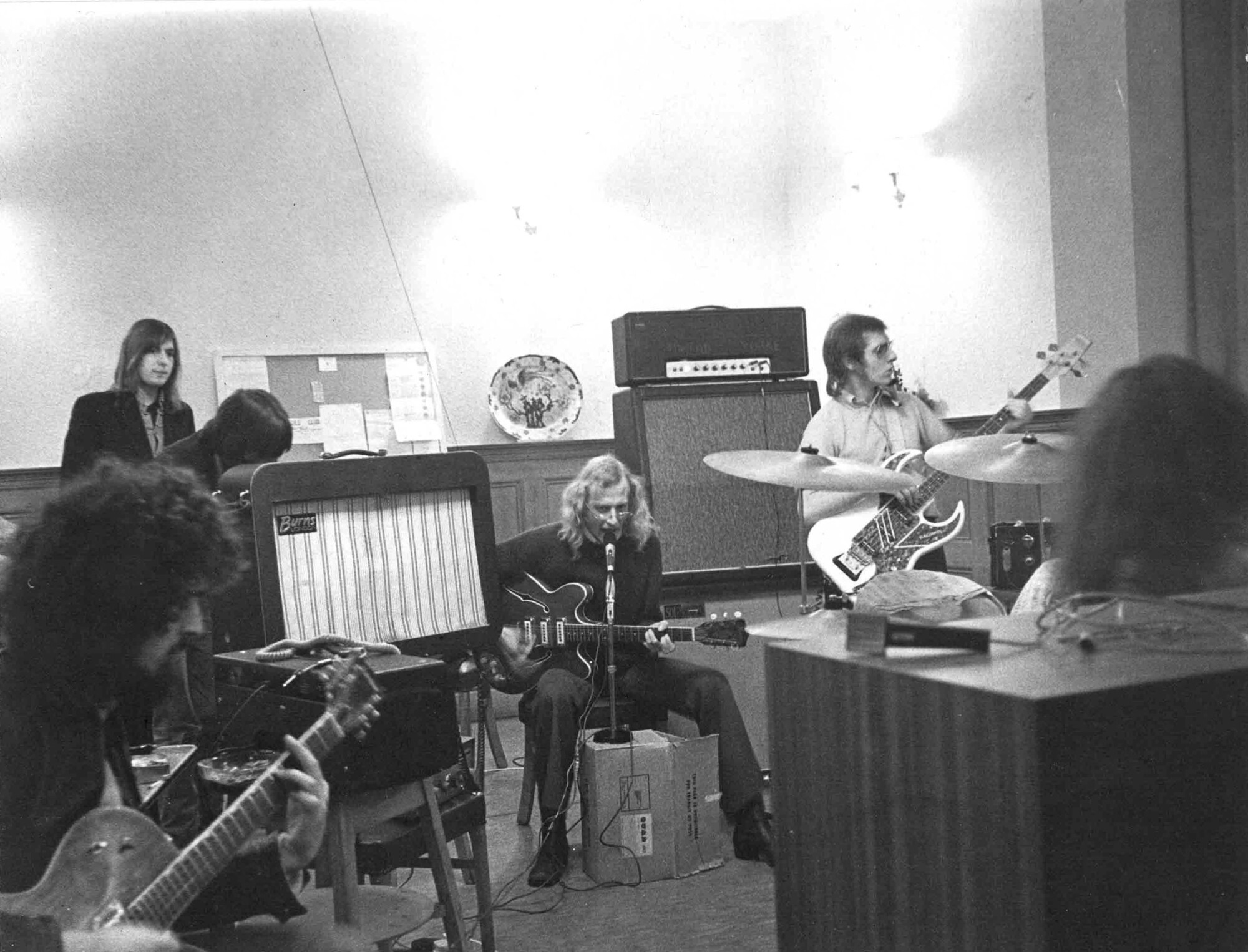

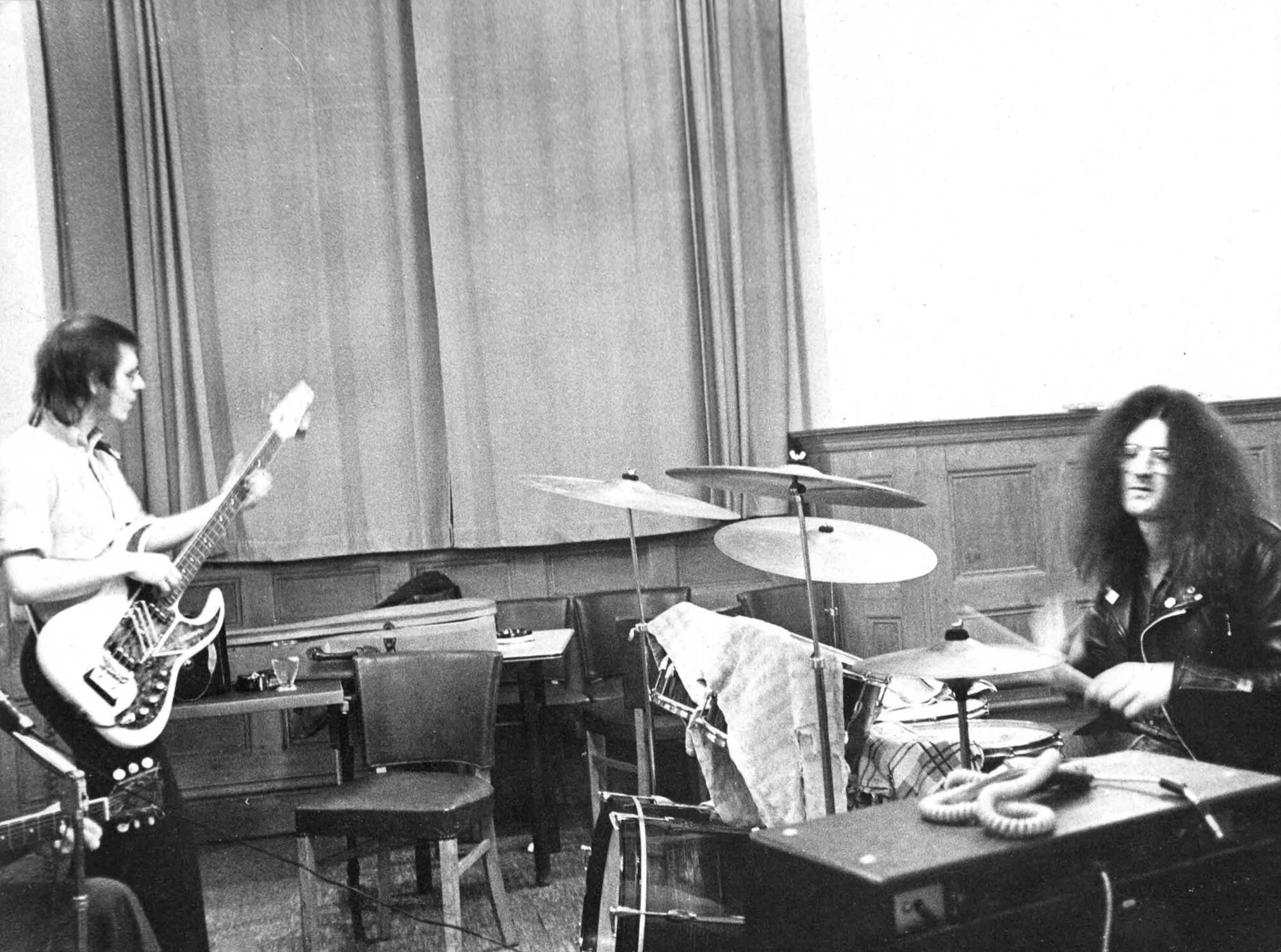

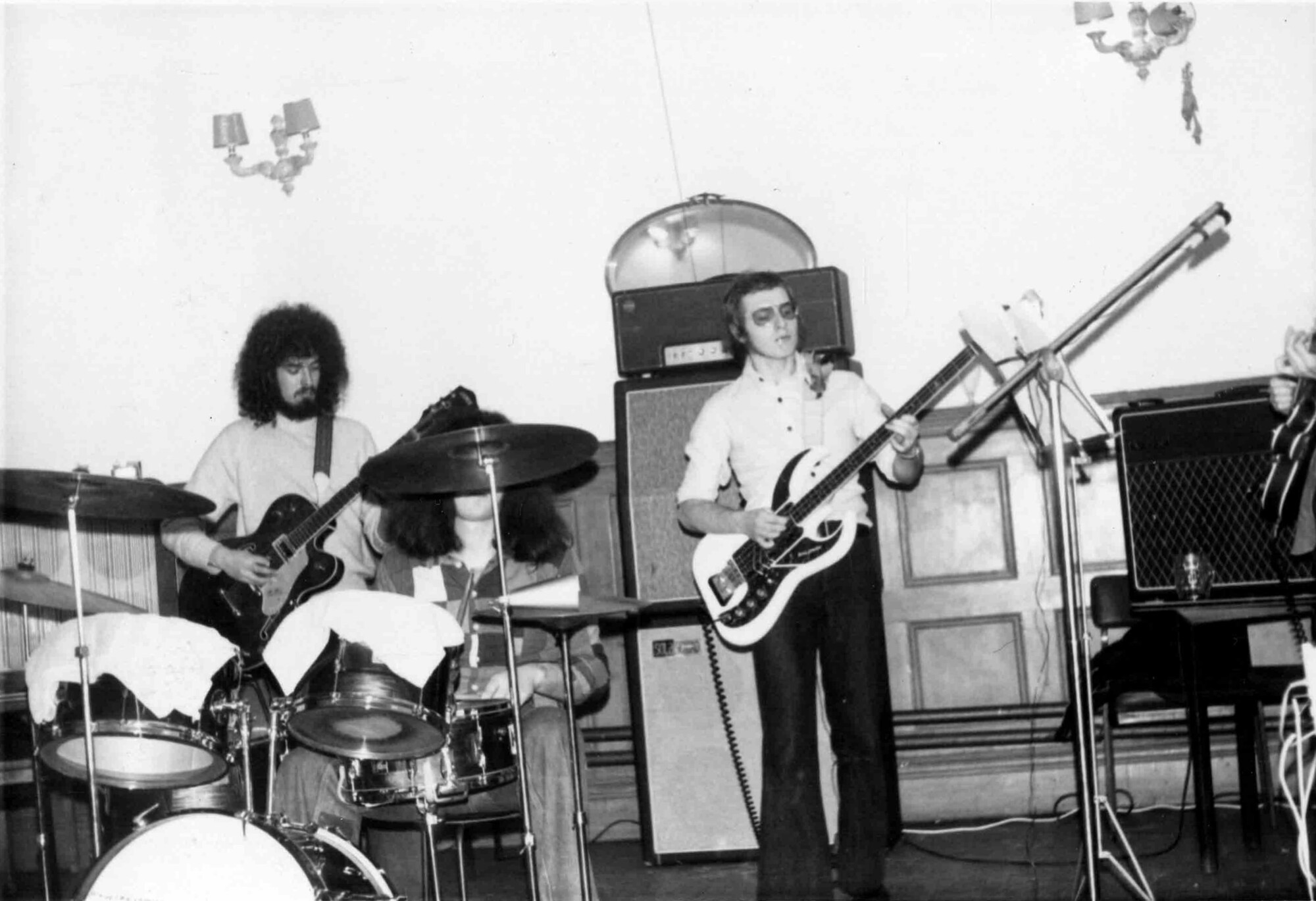

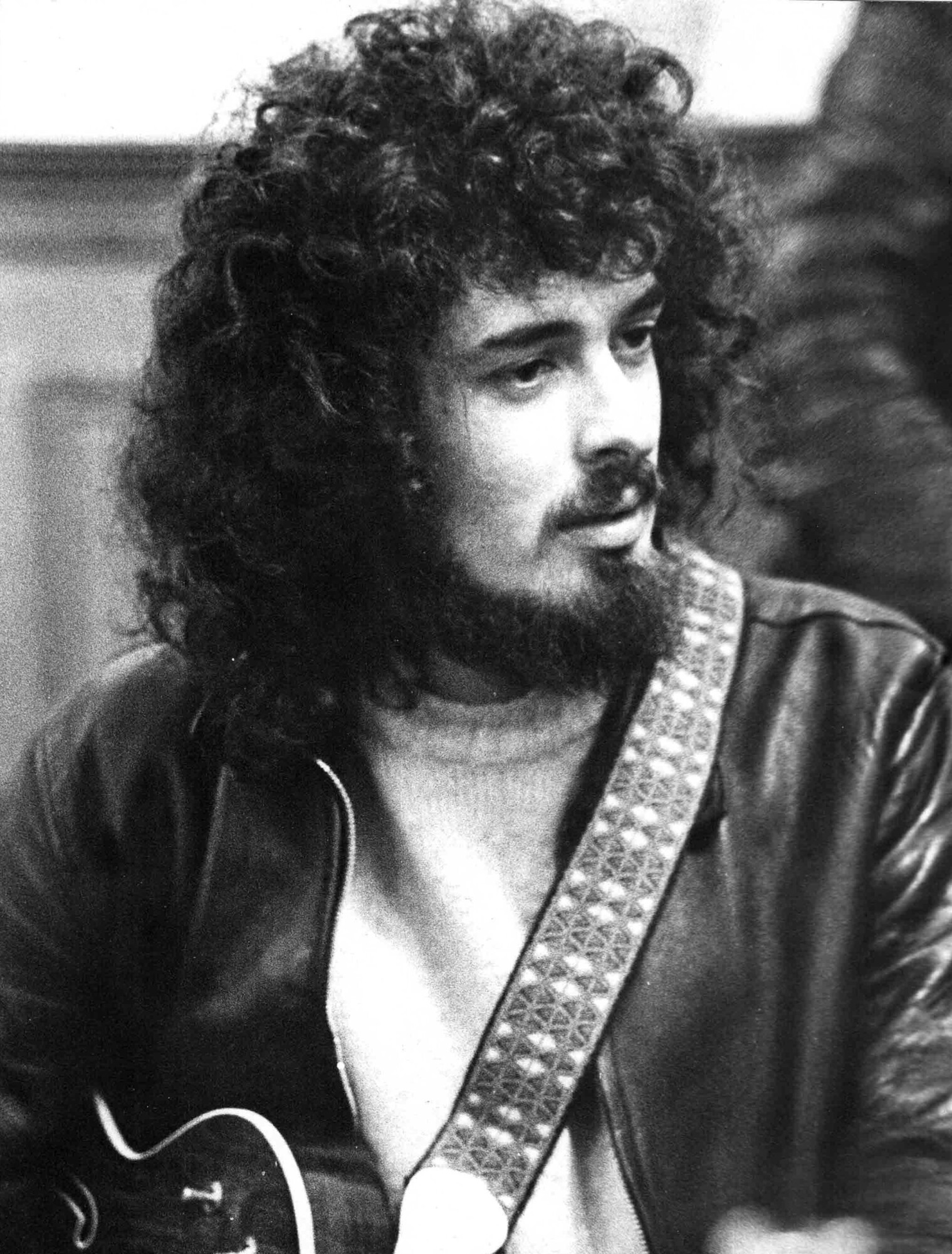

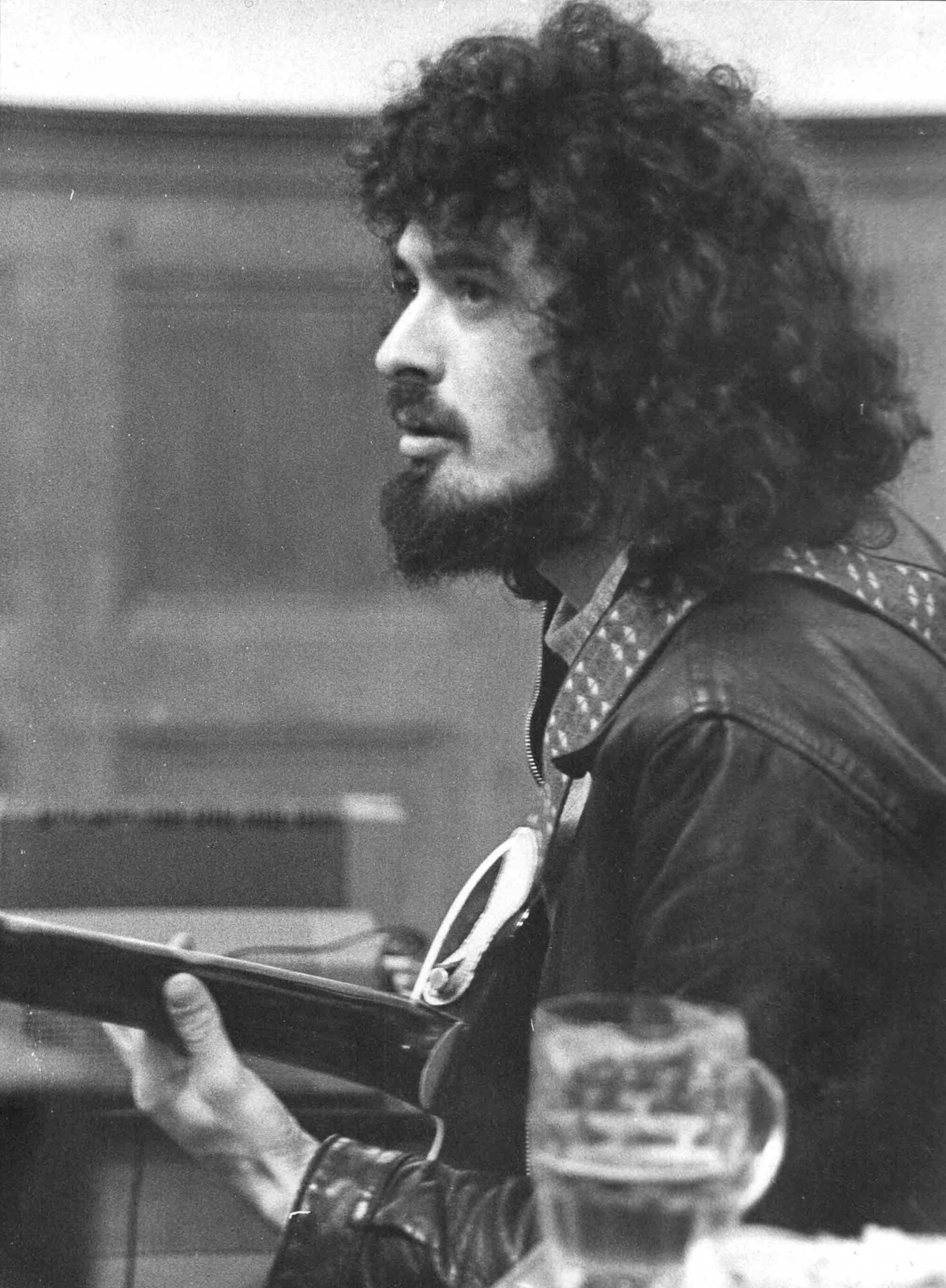

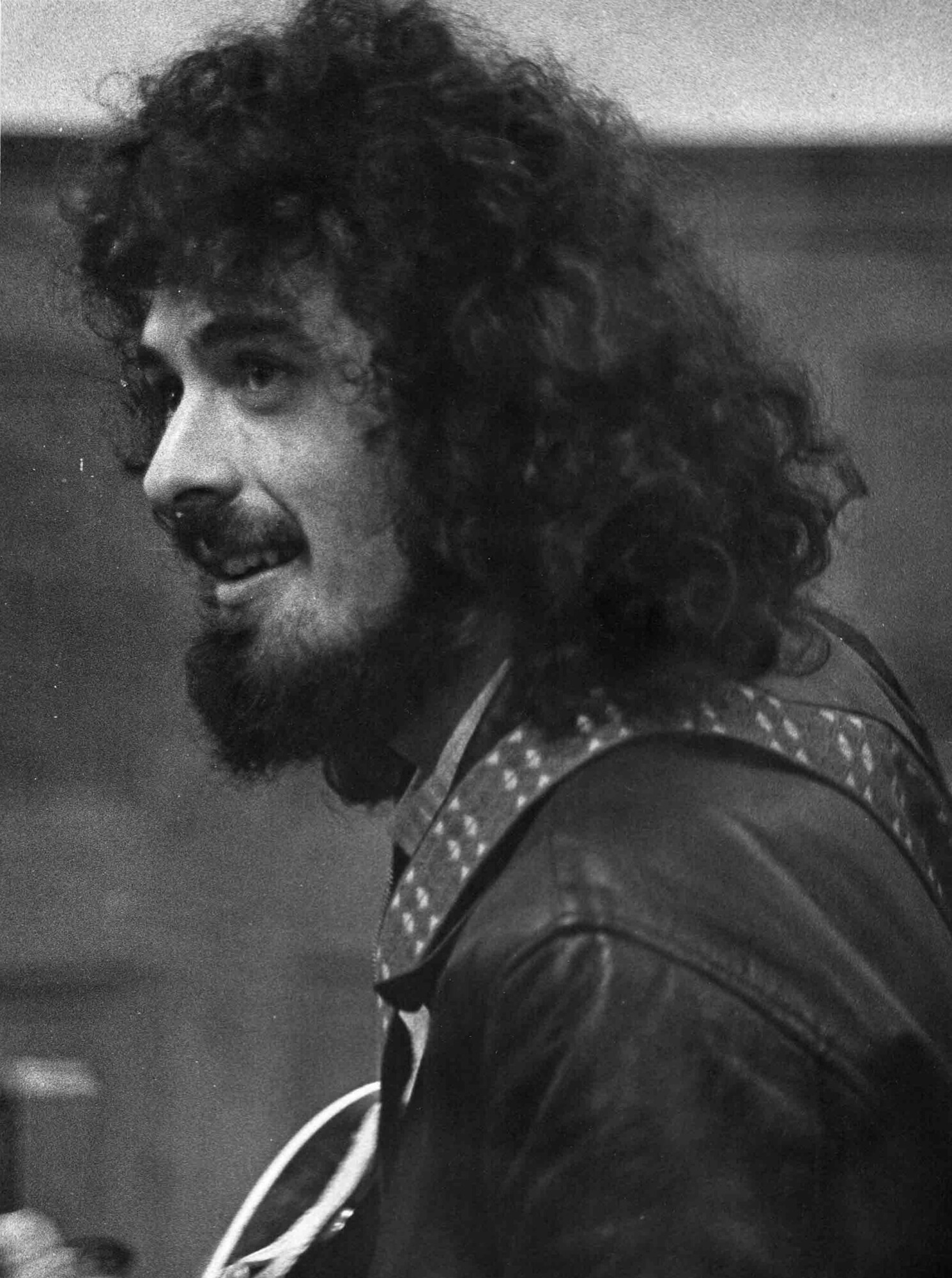

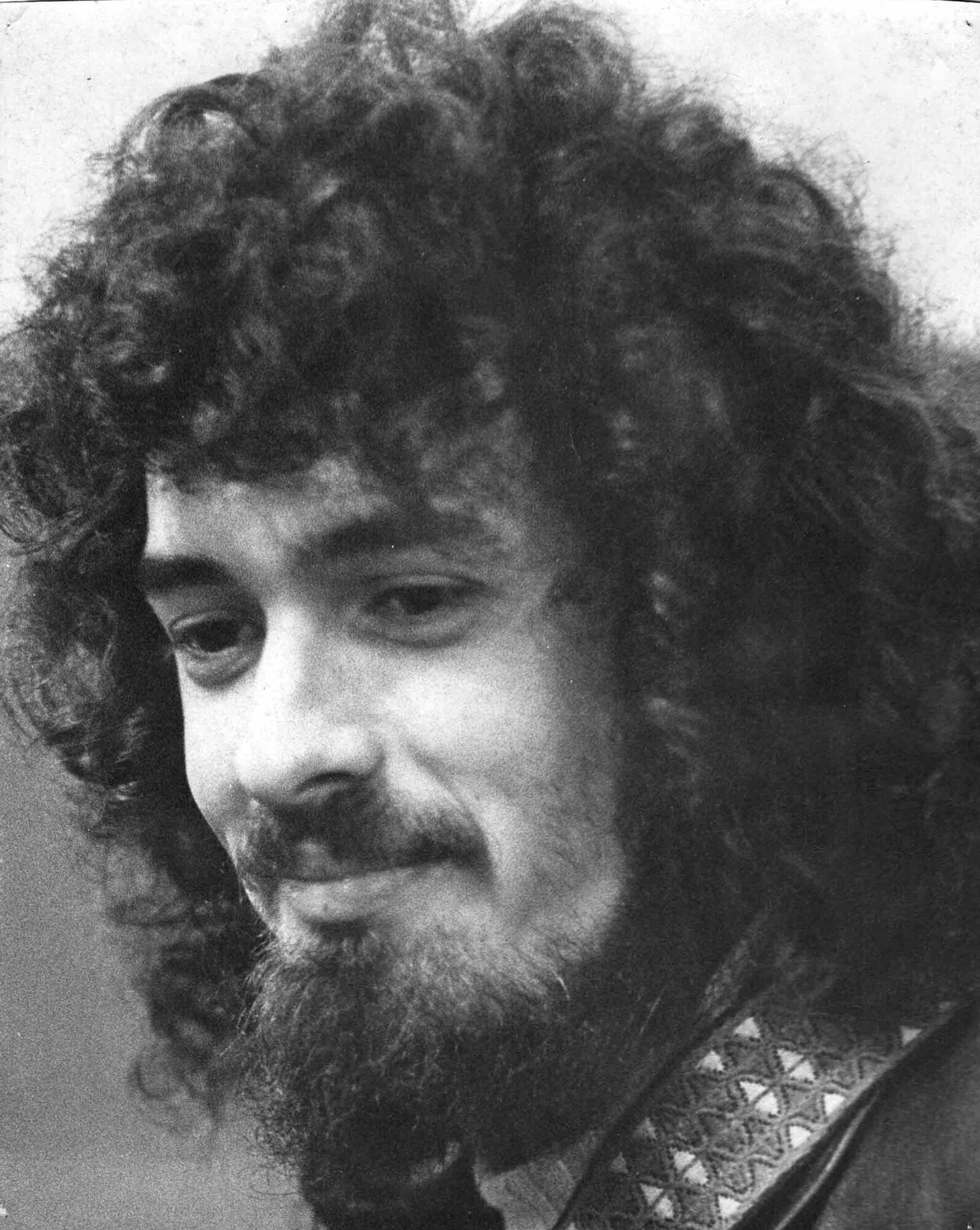

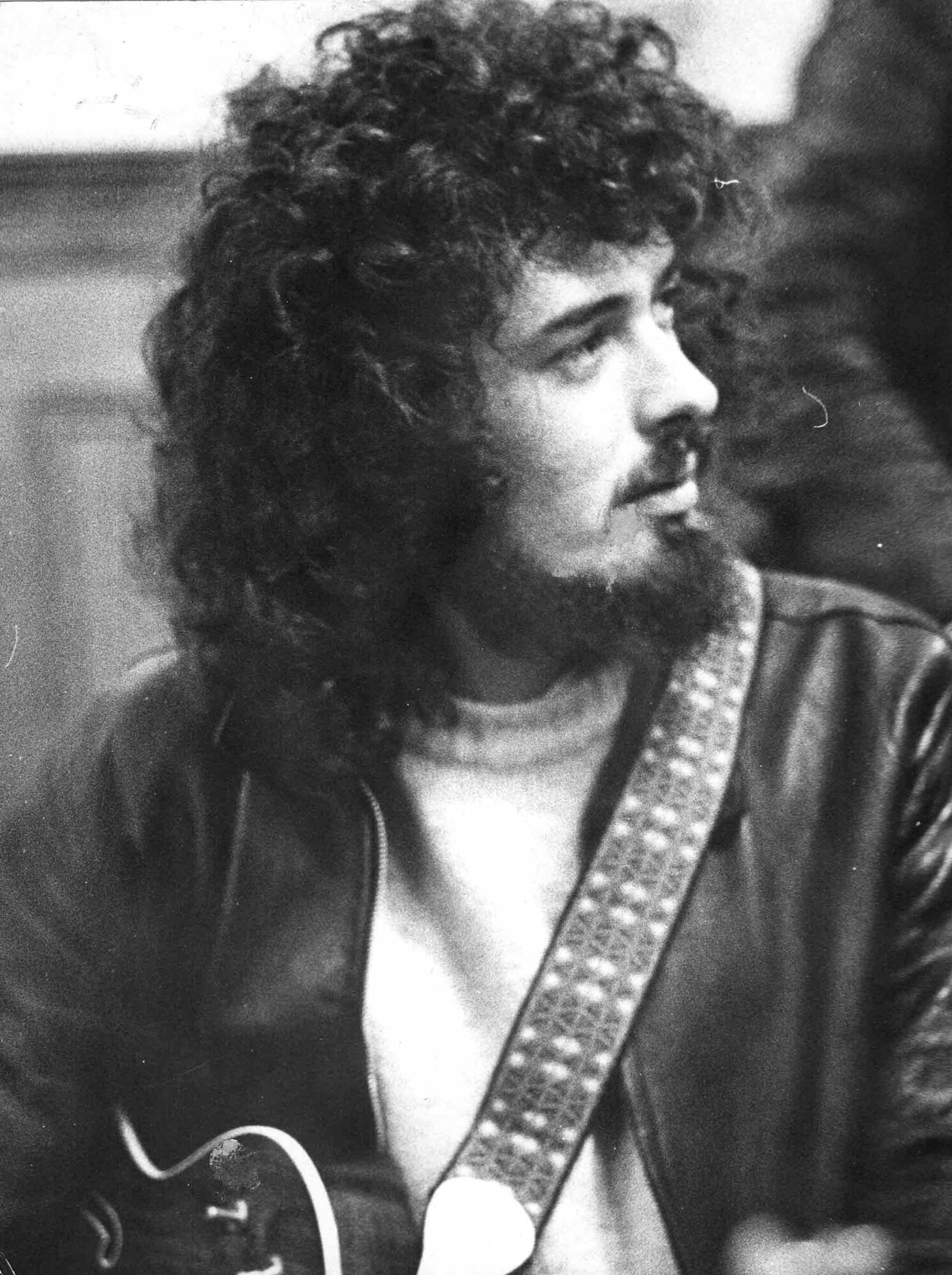

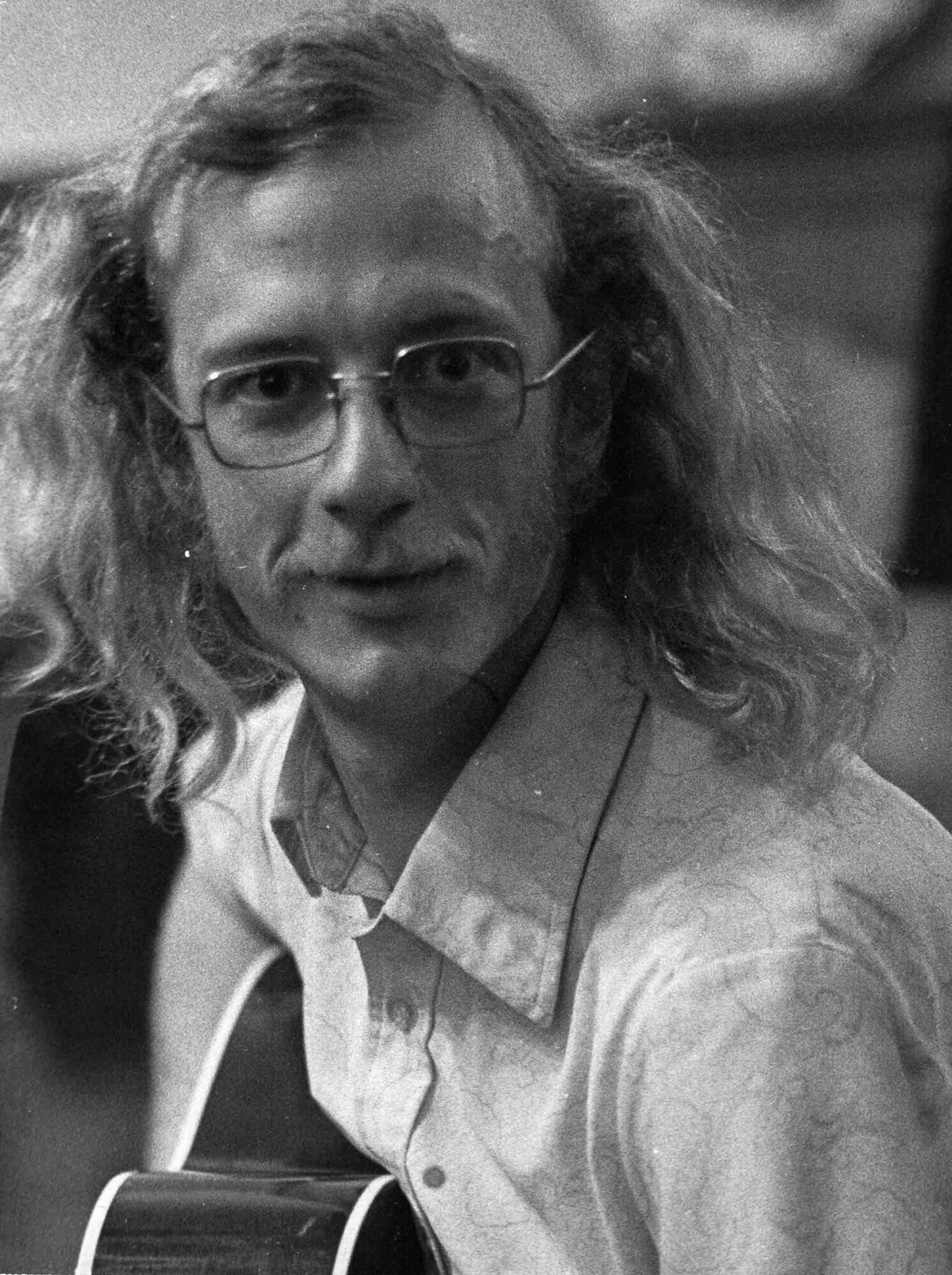

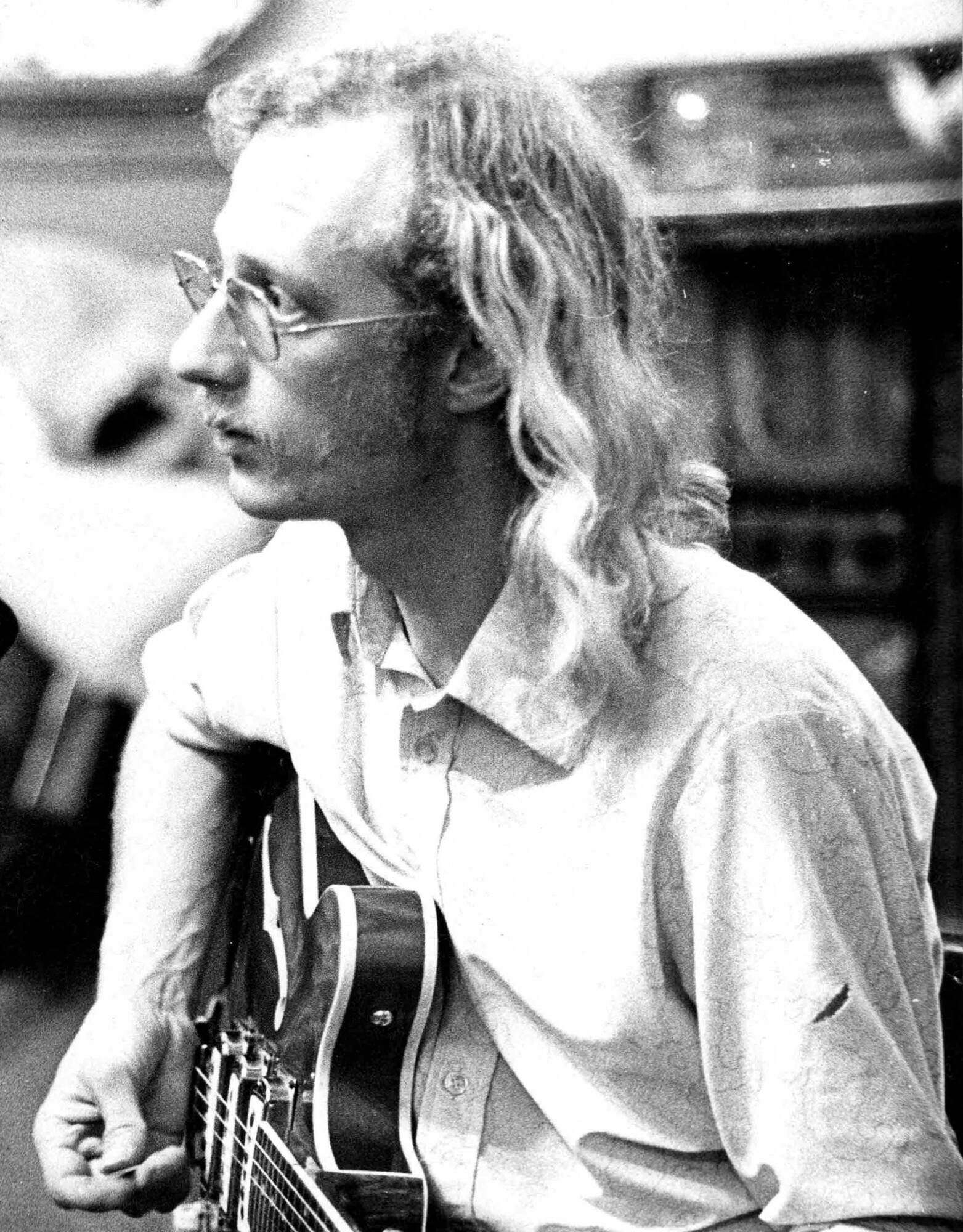

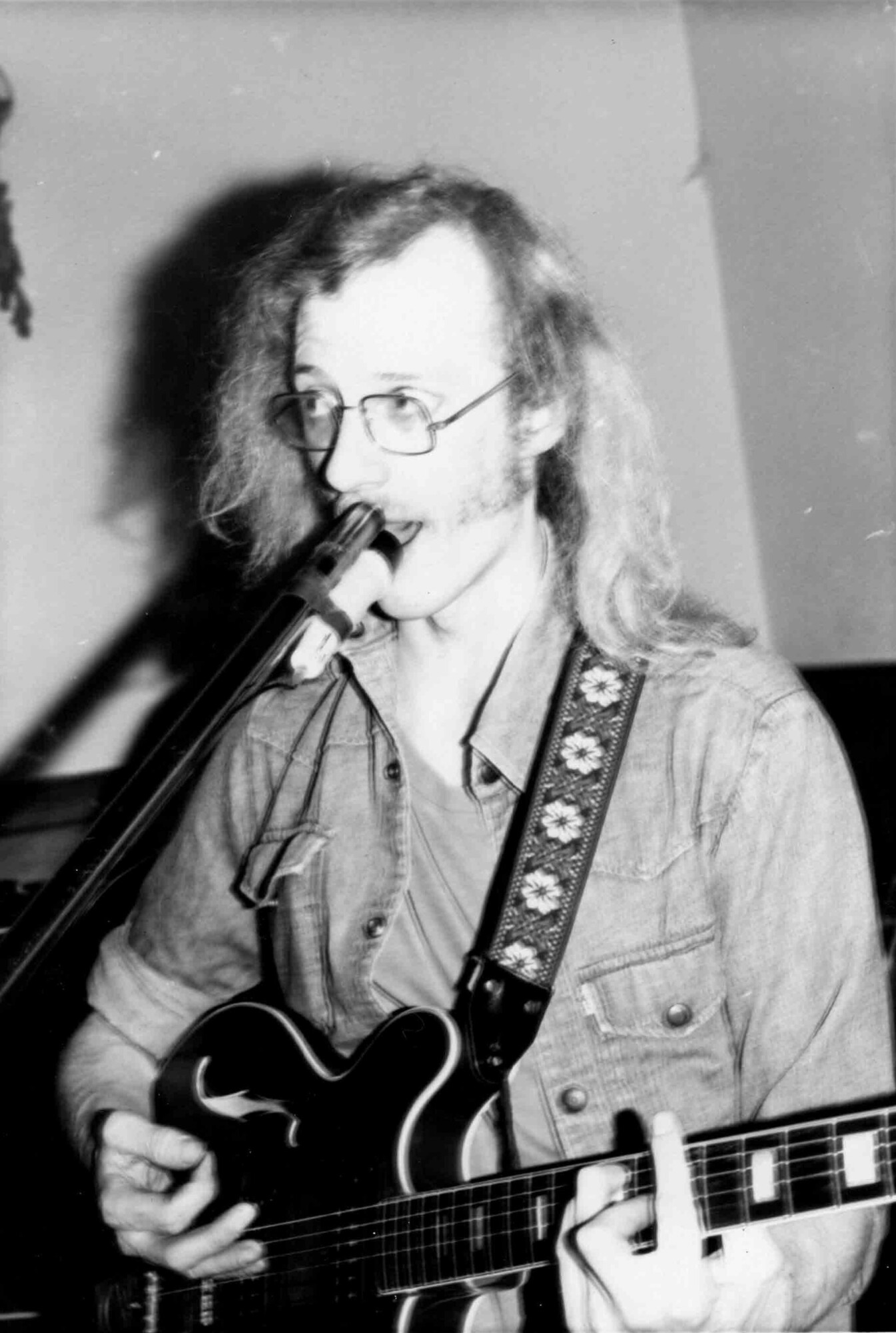

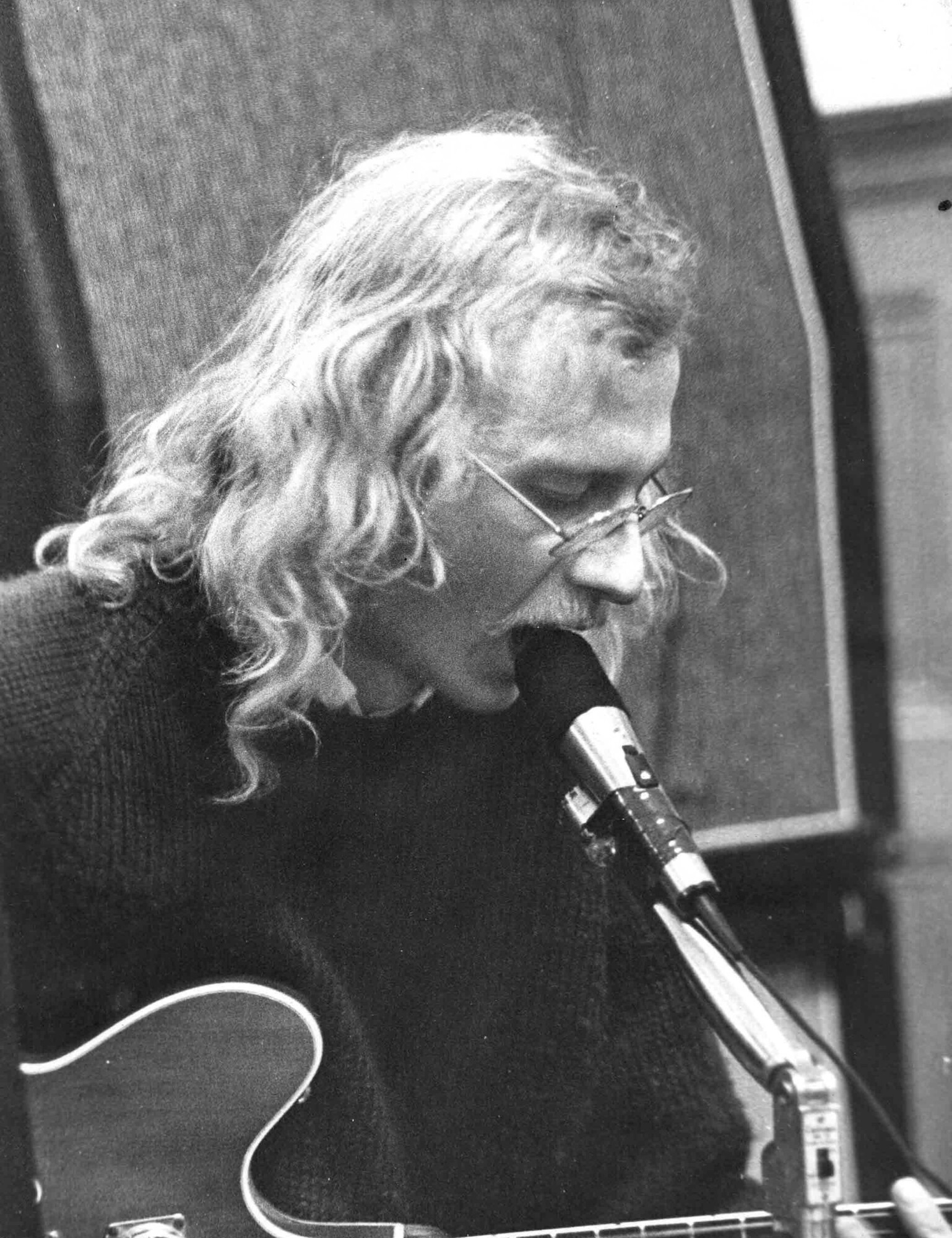

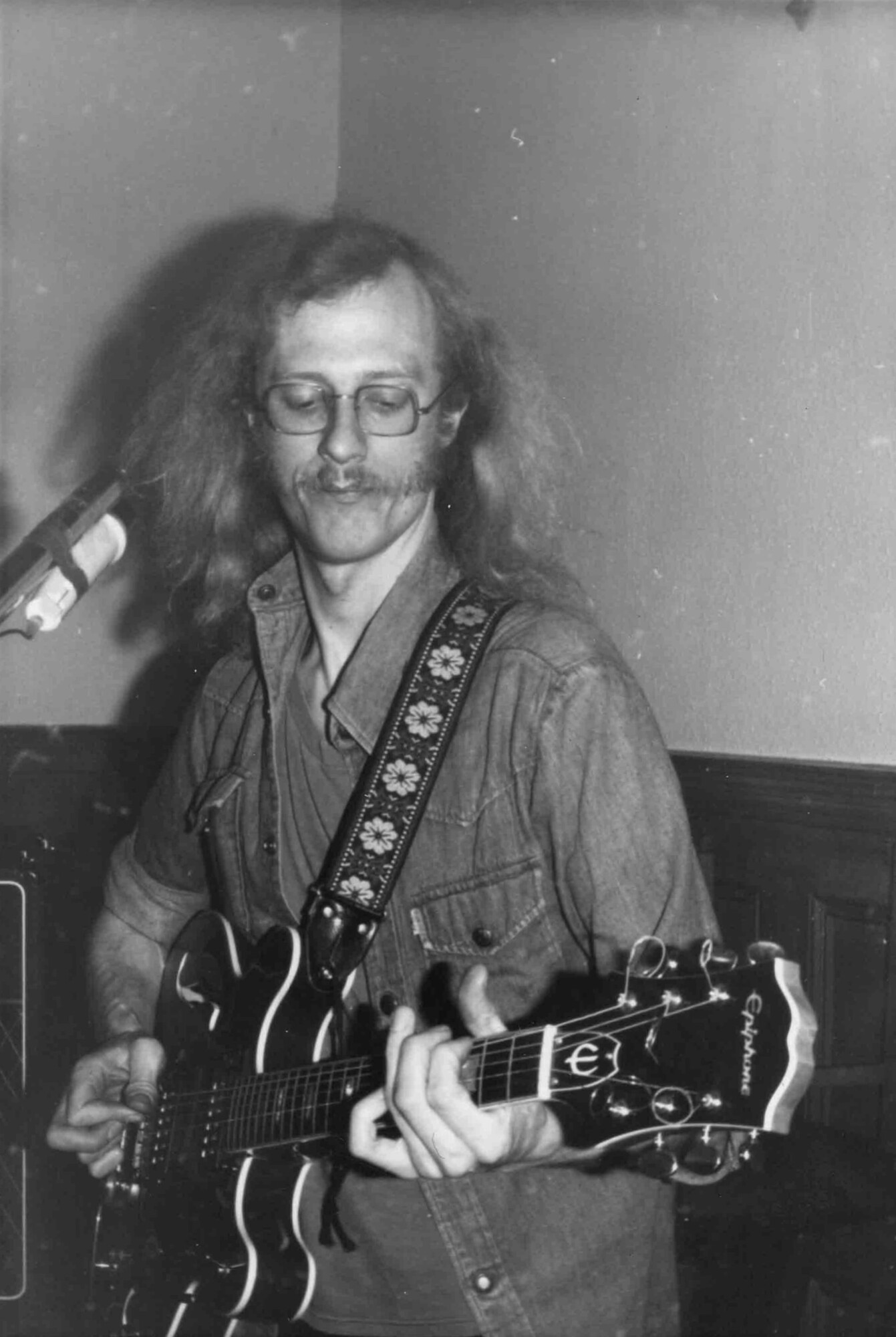

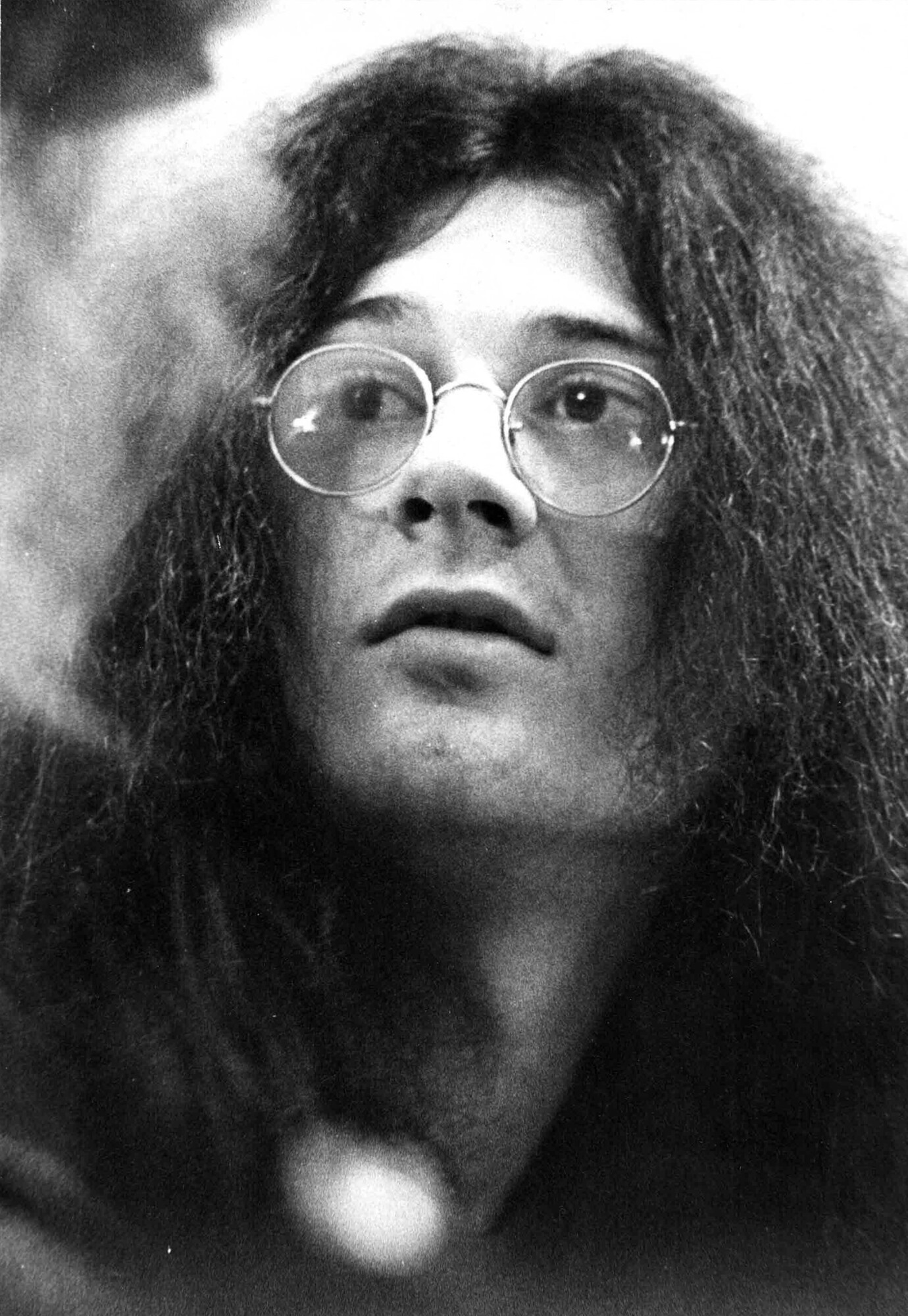

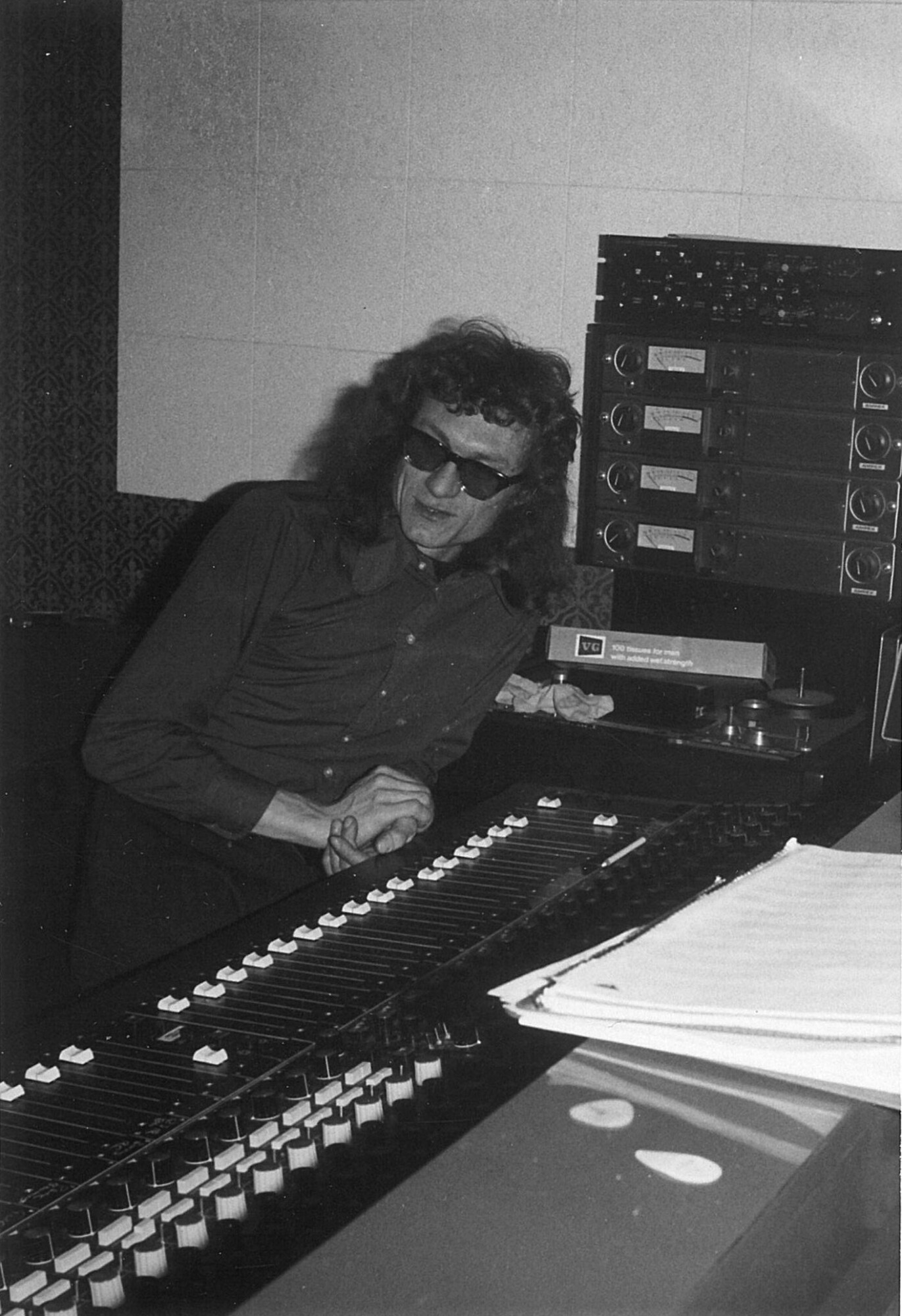

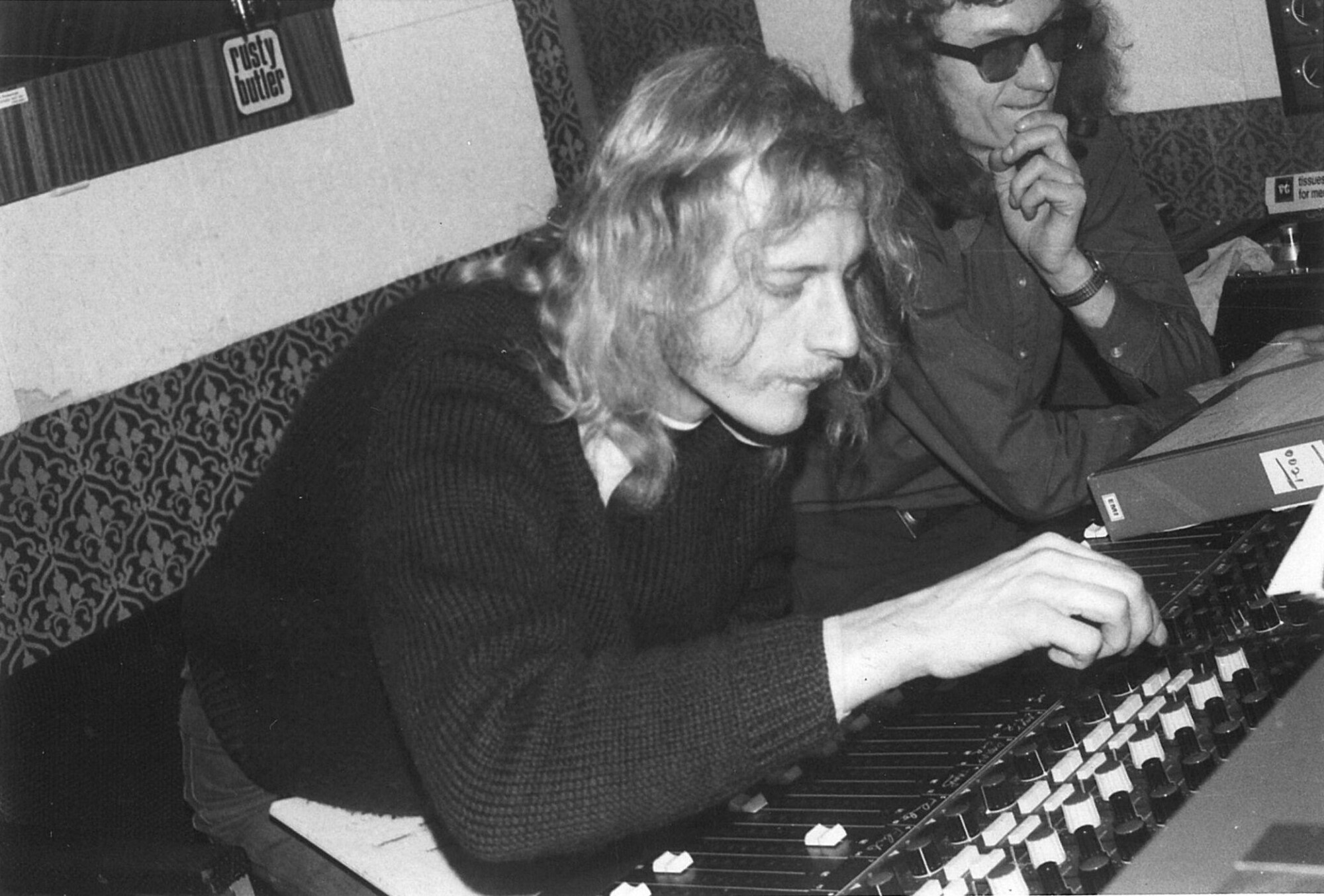

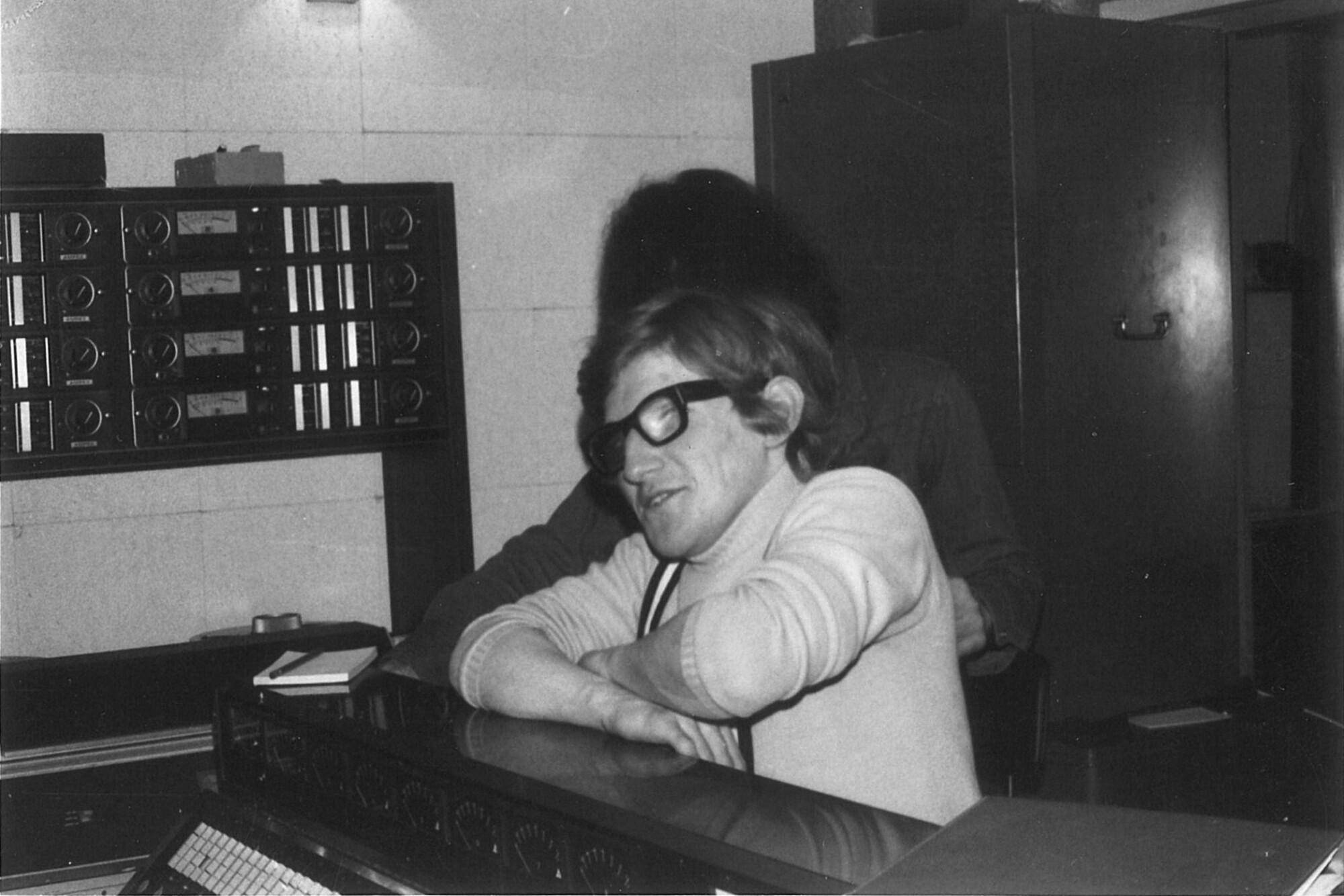

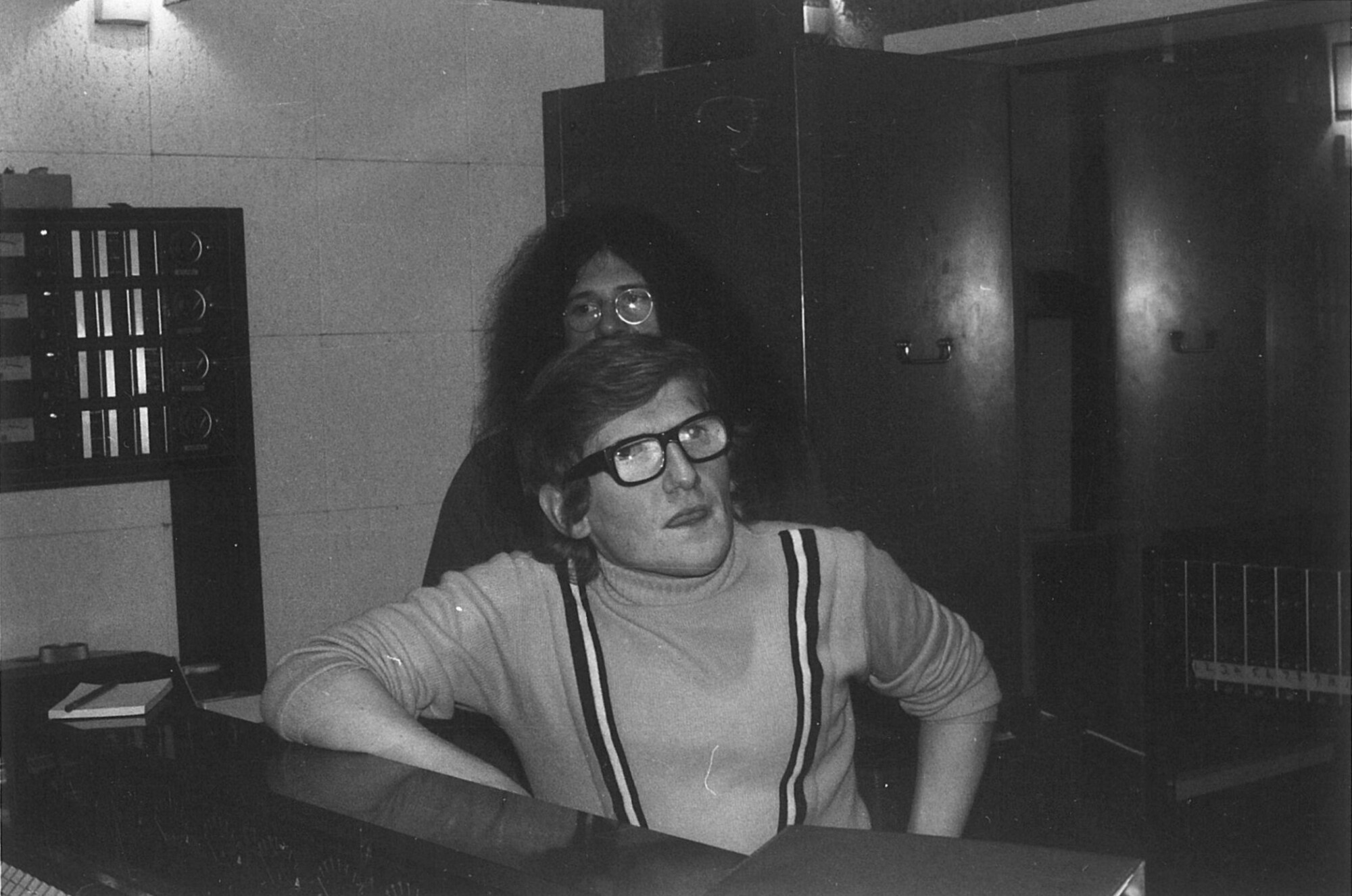

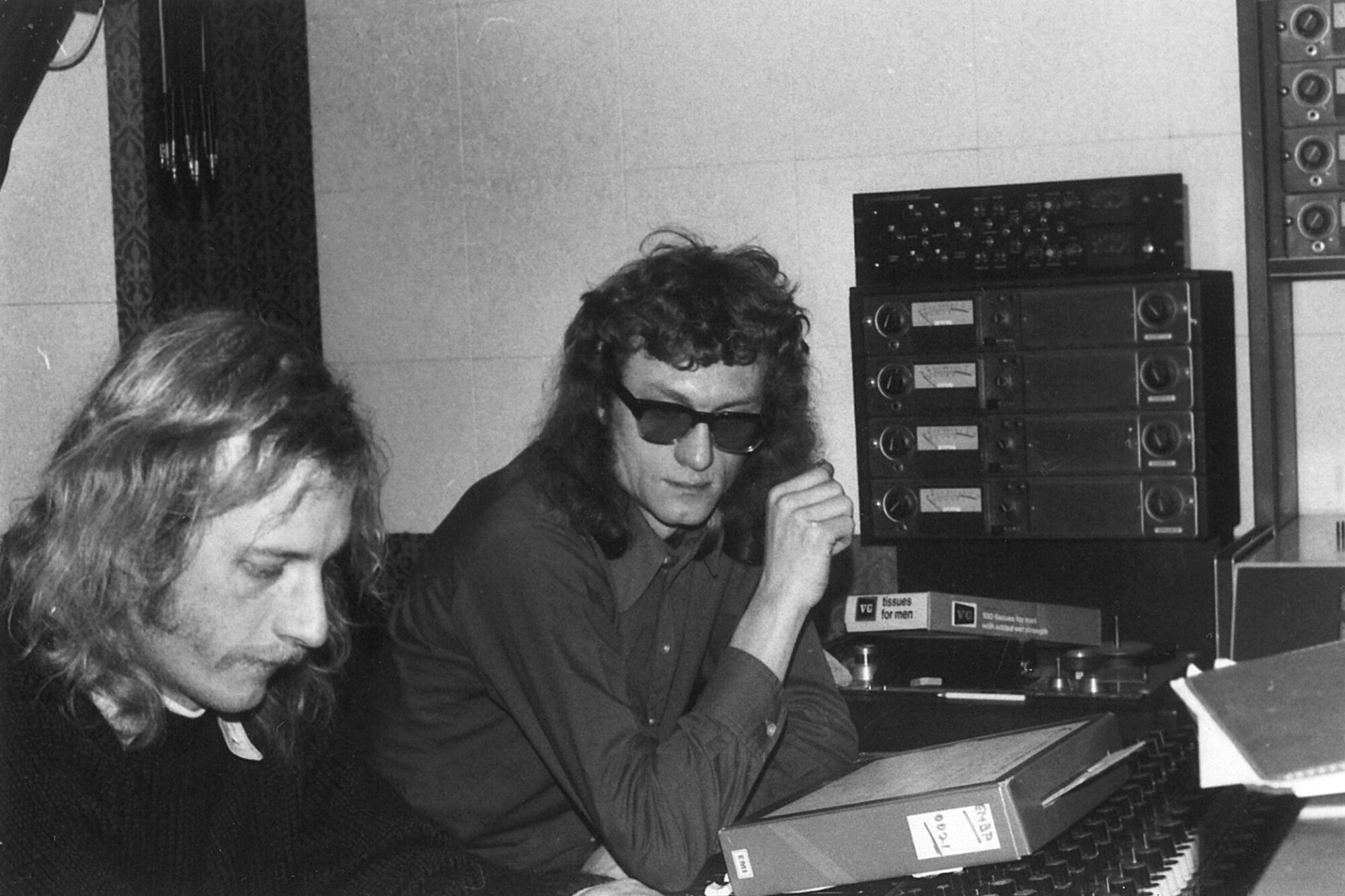

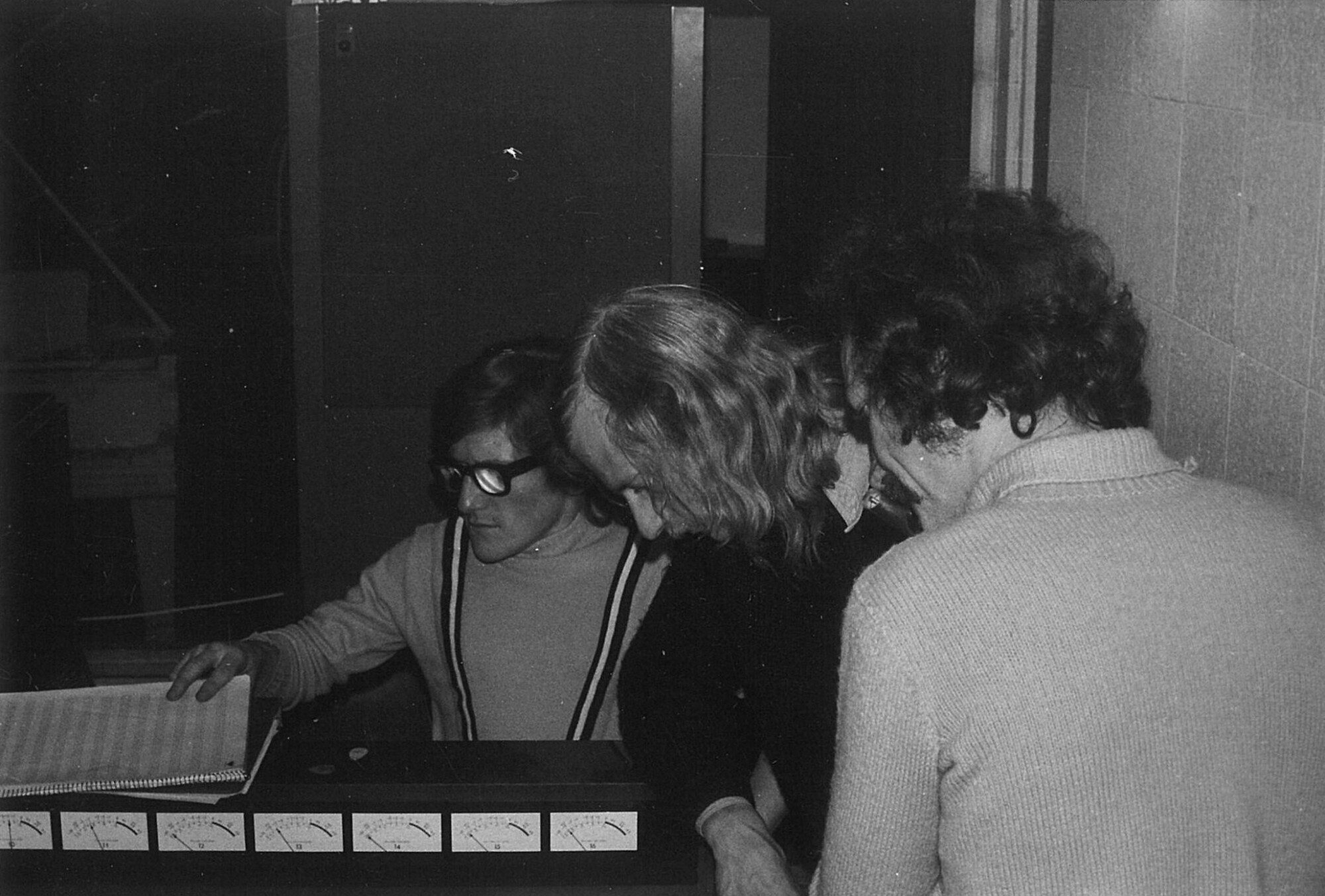

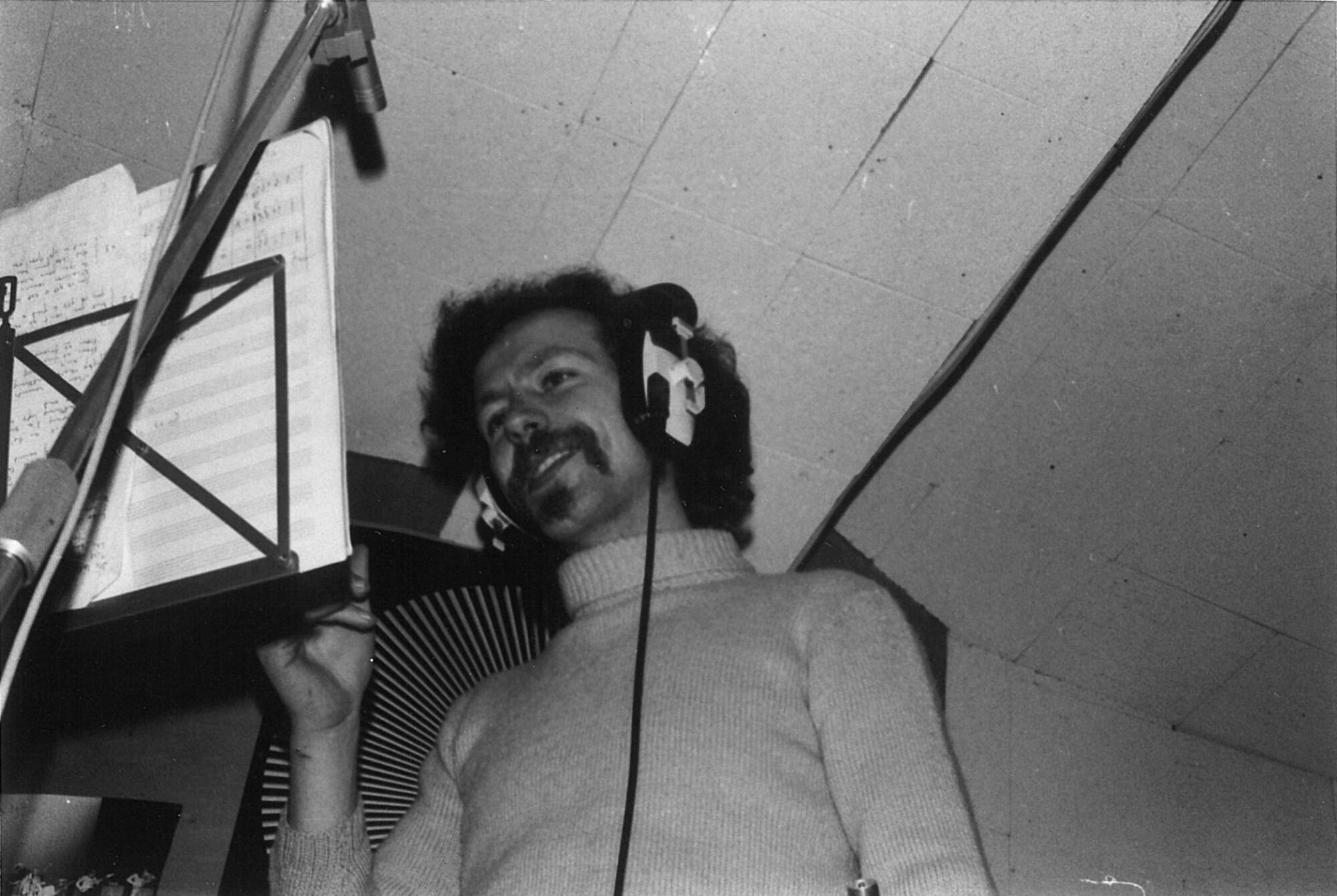

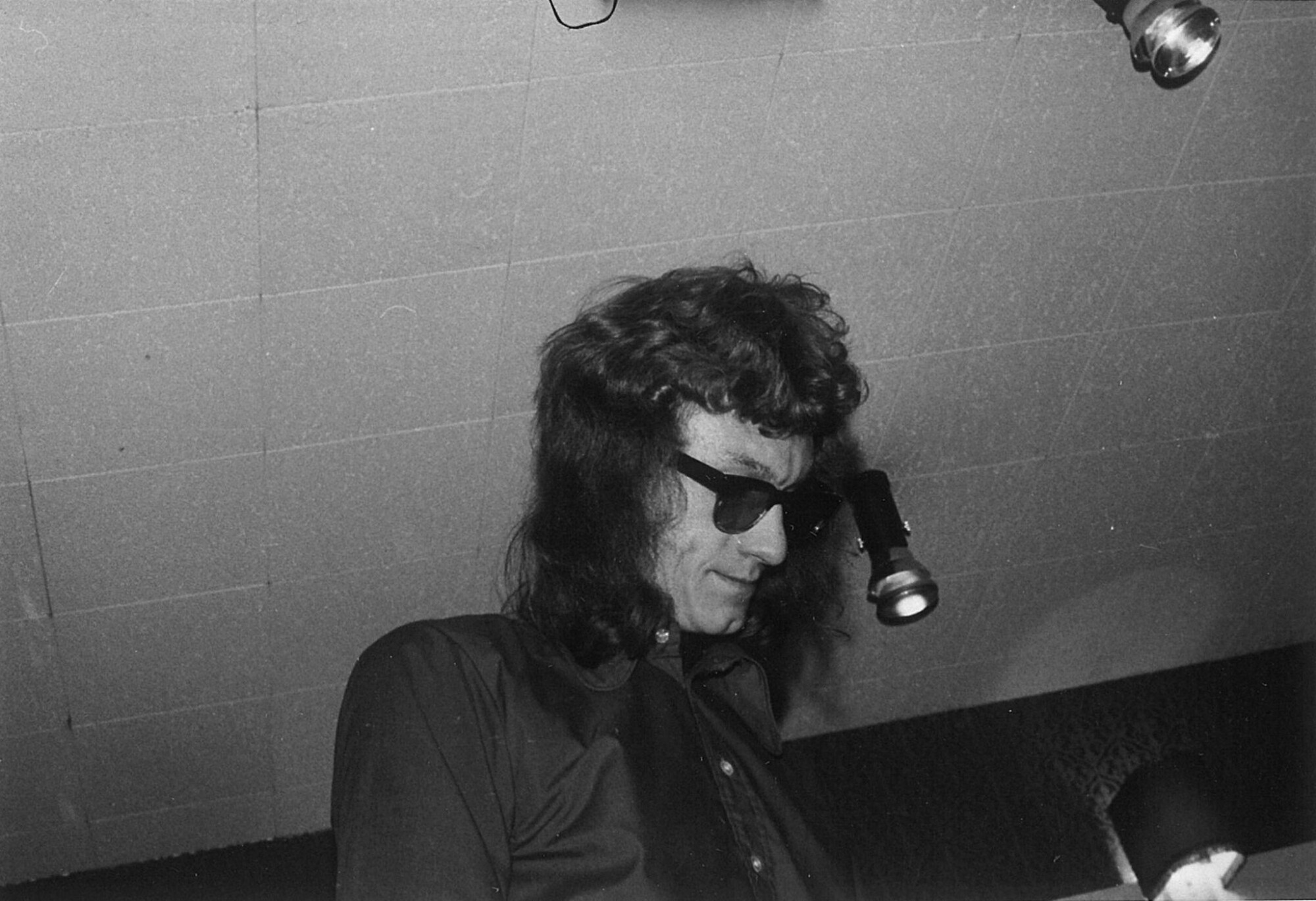

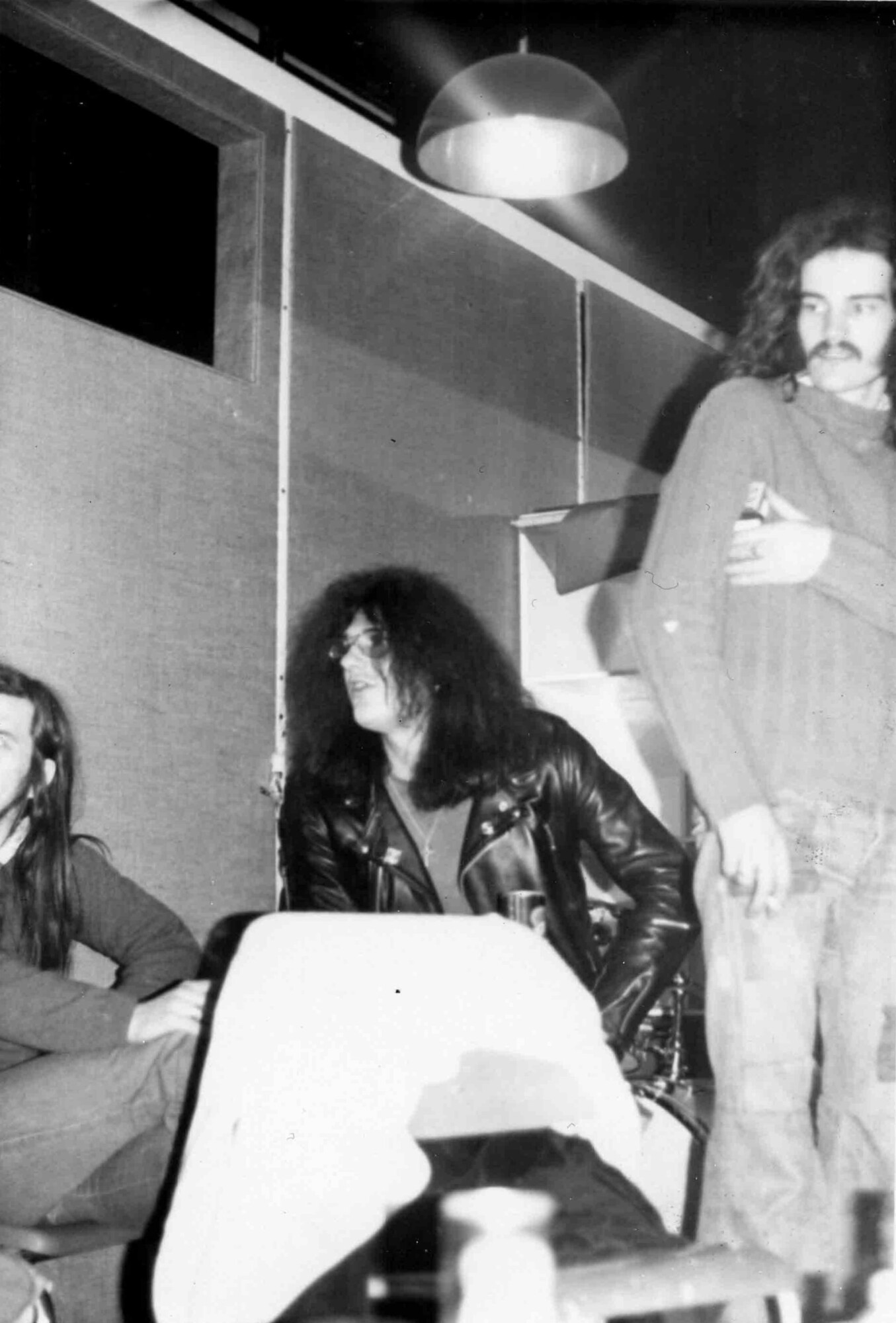

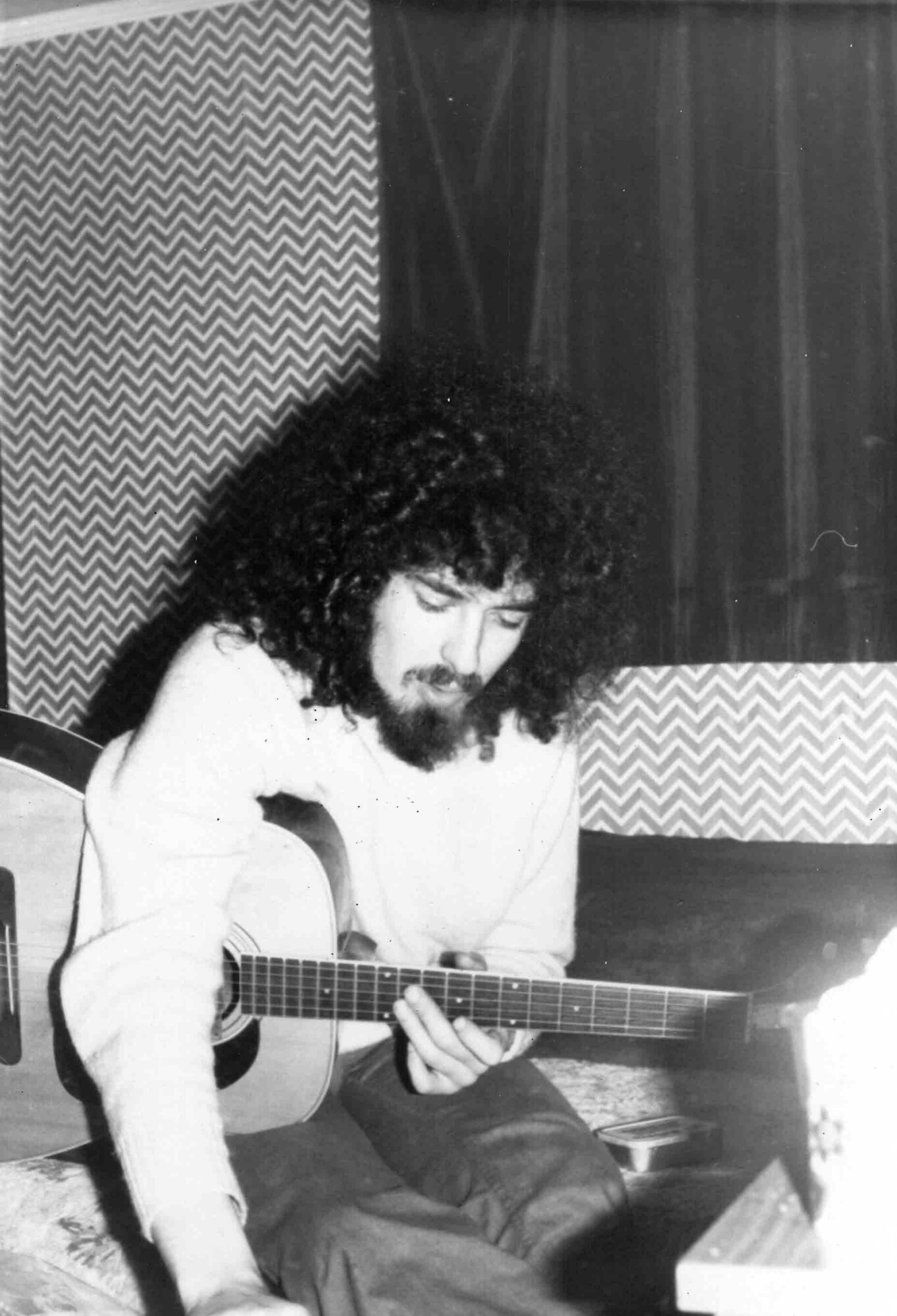

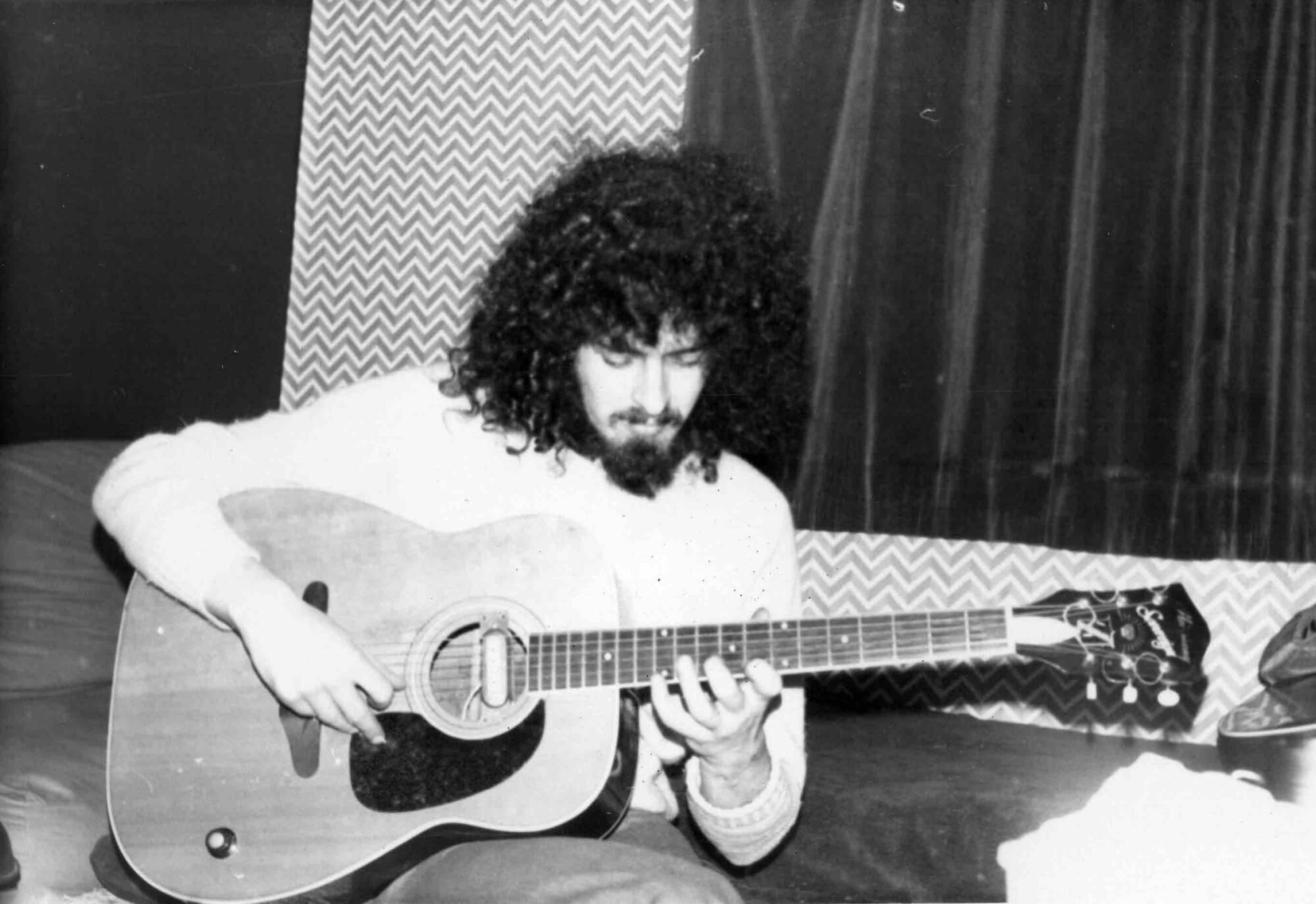

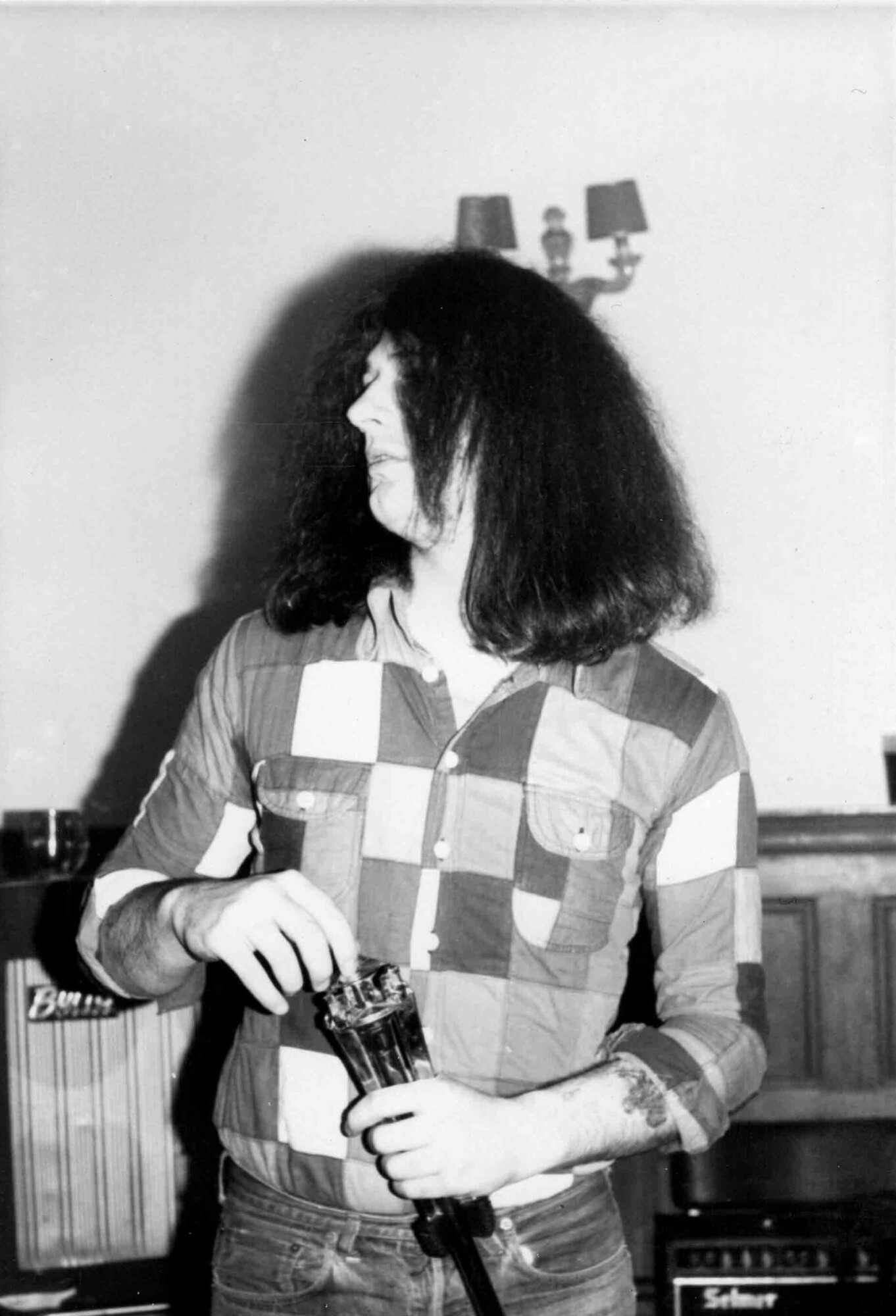

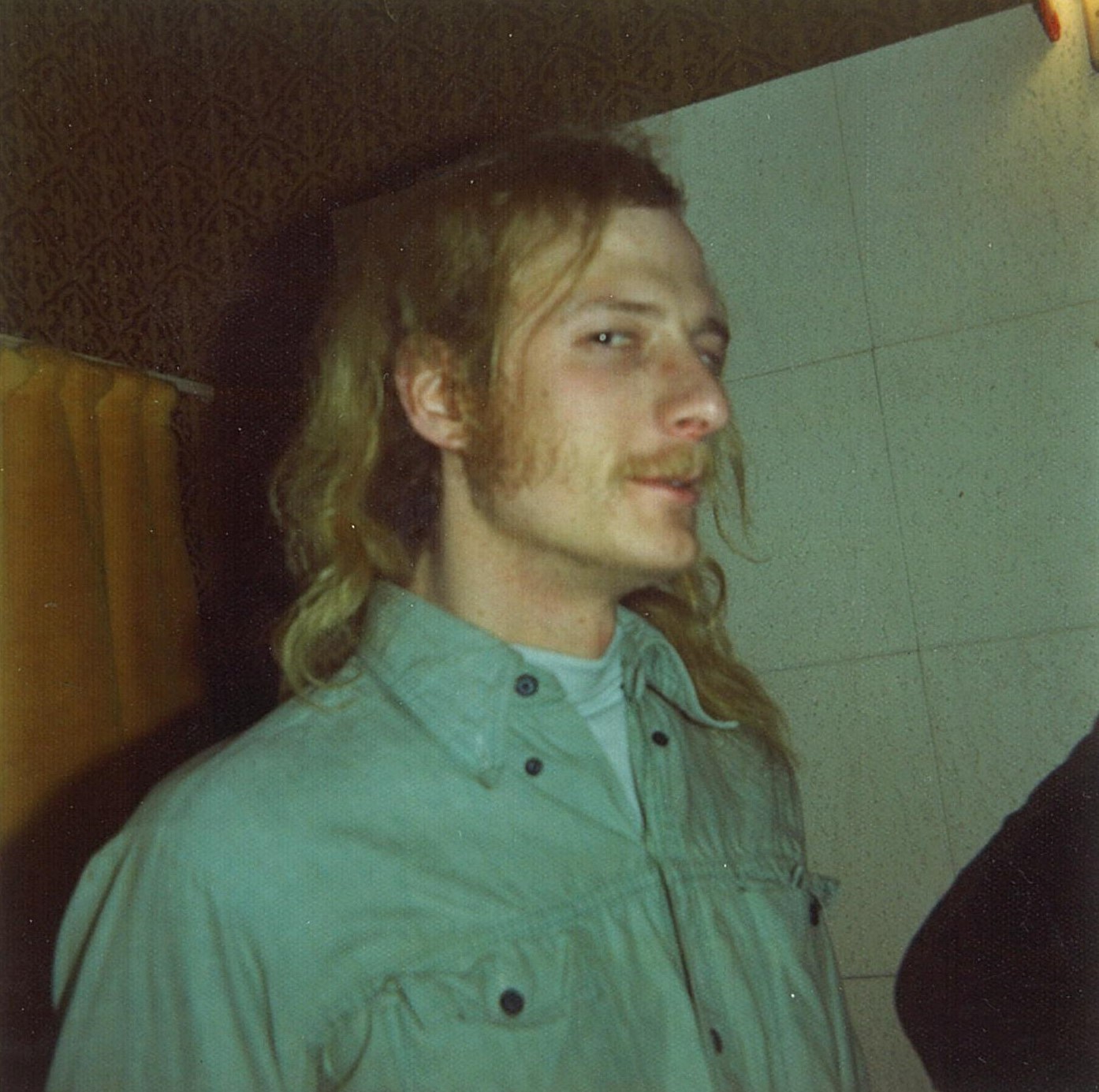

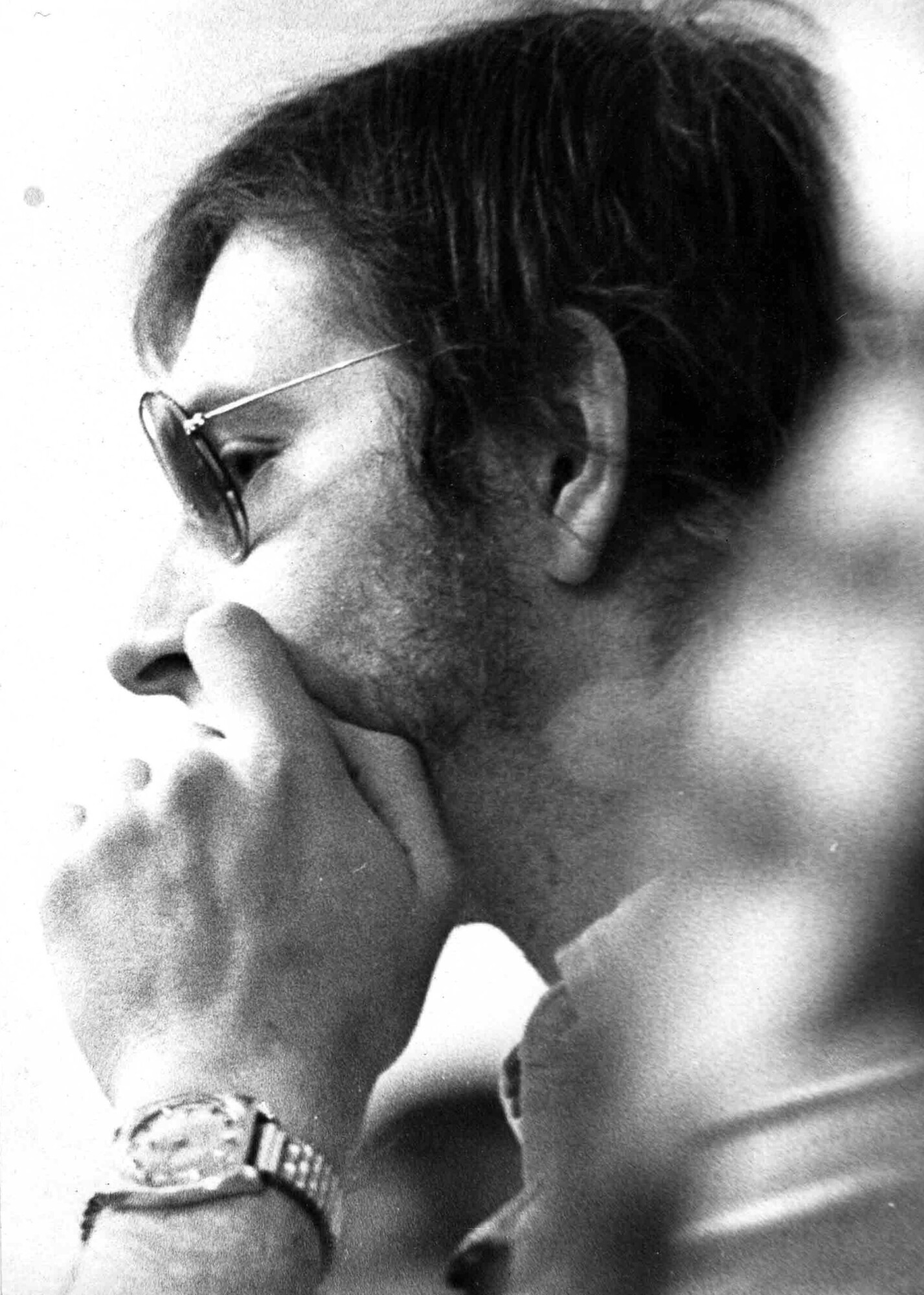

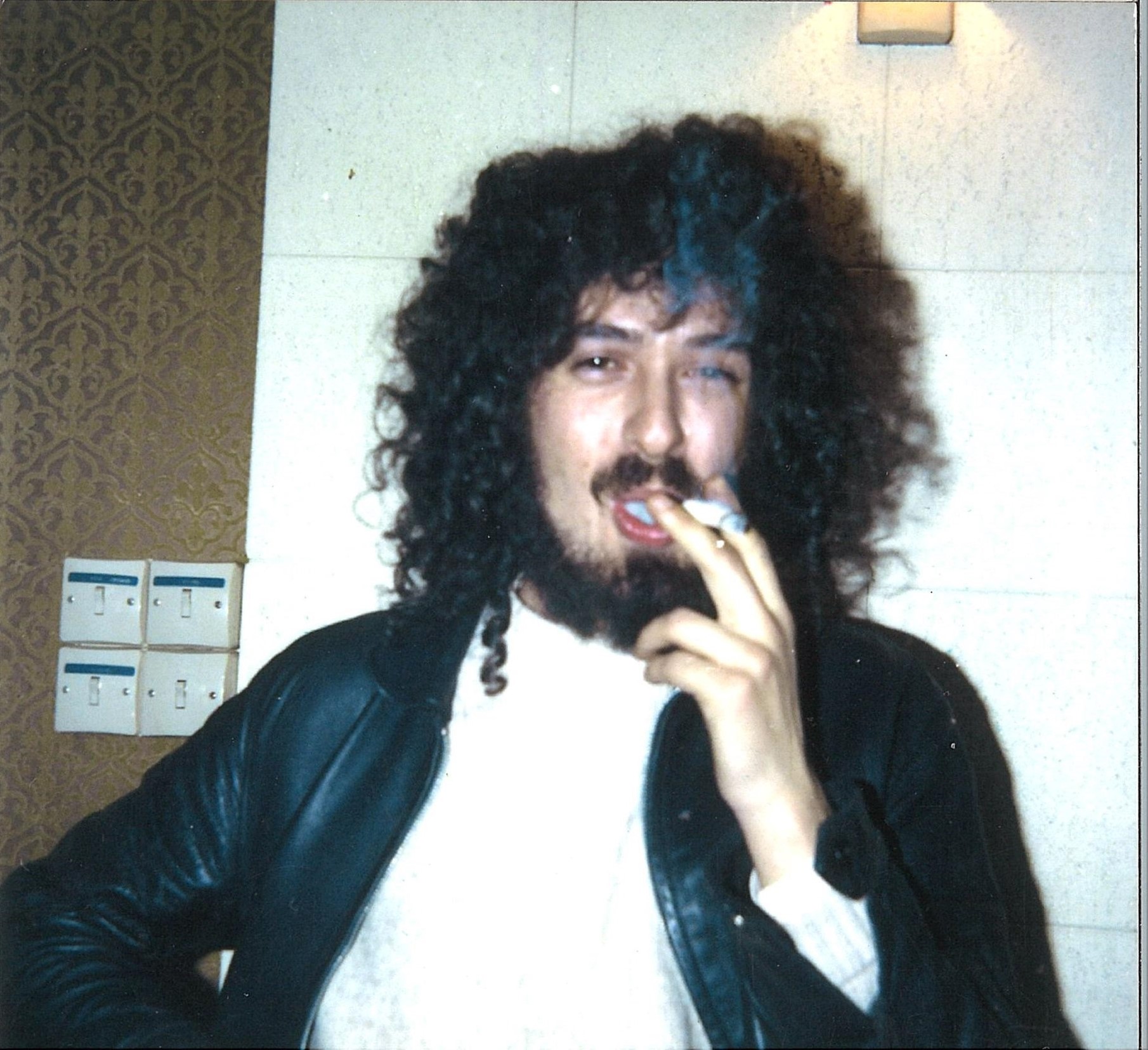

Headline photo: Raven rehearsing

Bright Carvings Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / YouTube

Terraplane | Interview | “A genuine underground”