Journey Through Alpha Centauri: Unveiling the Mysteries of a Forgotten Band

Alpha Centauri’s sole release, ‘Alpha Centaury’ is a staple private pressing, well-known among French prog collectors, and of equal gravitas to Skryvania and Rialzu.

However, up until now, no information existed about the band, as they didn’t seek publicity during their short-lived existence, while disbanding shortly after their album’s release. On the occasion of the resurrection of this gem by PQR-Disques plusqueréel, Hubert Laot offers ample light to the mysterious constellation of Alpha Centauri.

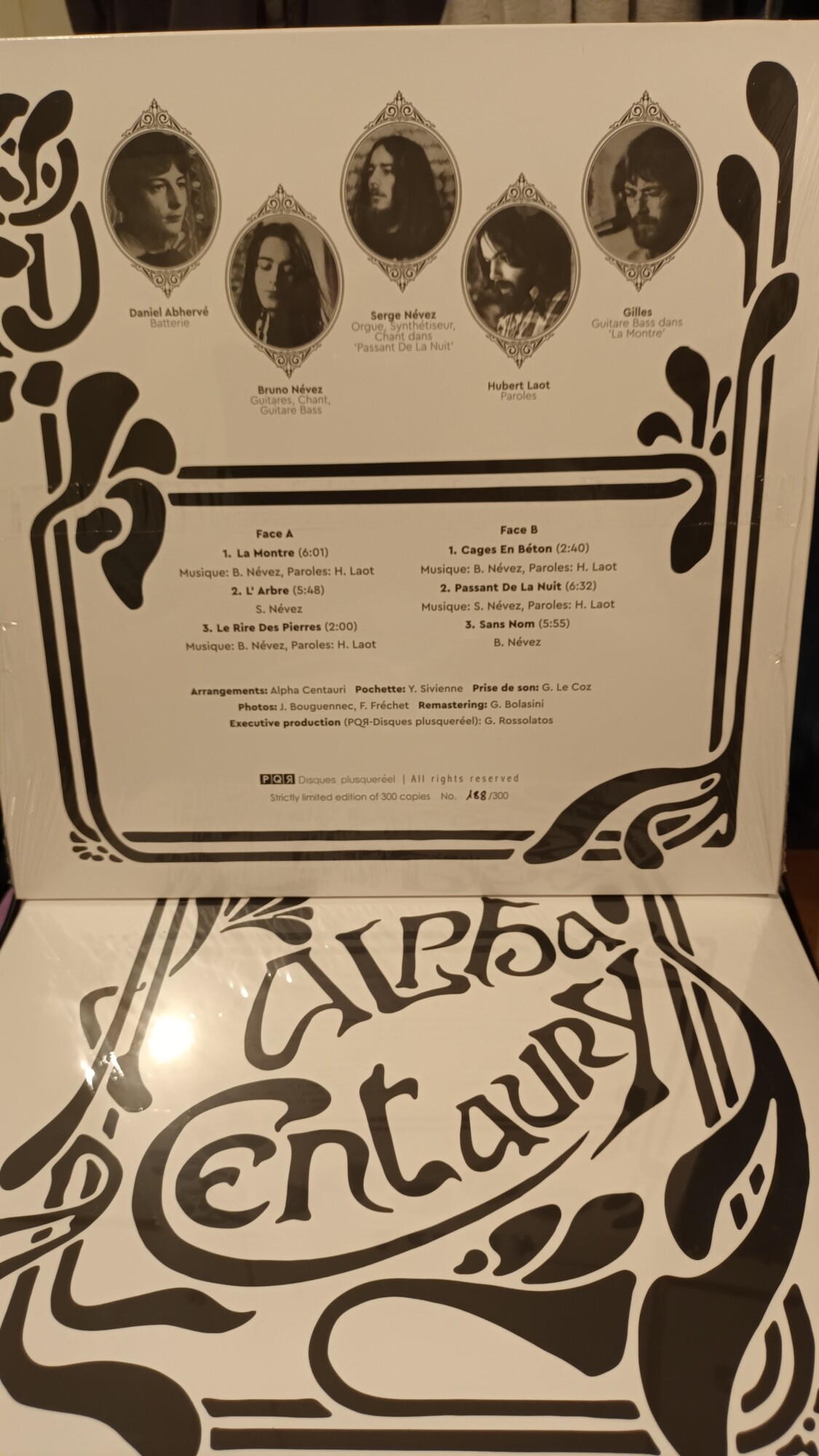

Alpha Centaury is available in a strictly limited reissue of 300 hand-numbered copies (150 on black and 150 on marble vinyl), remastered by Gustavo Bolasini, with a redesigned back cover and a 2-page insert including the band’s proper biography.

“A record recorded in the urgency of an inevitable dislocation”

Who were the original members of Alpha Centauri, how did you meet, and when and where was the band officially formed?

Hubert Laot: Alpha Centauri was born from a meeting between Bruno Névez and me at the end of the year 1974. However, the name Alpha Centauri already existed. Bruno and his brother Serge had indeed registered the name earlier. But this first version of Alpha Centauri was an orchestra that played covers at balls and weddings to make a little money. When I met him, Bruno was 16 years old, he was a high school student. I was 20, and I had just decided to give up my engineering studies, which hardly inspired me, to devote myself to a career as a singer-songwriter. A first tour made during the summer of 1973 convinced me to change my path. That day, Bruno and I talked about music, and he asked me to listen to a piece that he was writing to set to music a poem by Victor Hugo. I simply asked him whether he would prefer an original text rather than a classic of French poetry. The next day, I wrote “Cages en Béton,” the first song that appeared on the album less than two years later. The band was formed shortly thereafter: Bruno Névez (guitar, voice, 16 years old), Serge Névez (keyboard, voice, 17 years old), Daniel Abhervé (drums, 17 years old), and myself, Hubert Laot (guitar, voice, 20 years old). The life of the group was ephemeral: less than two years. If the three stars of the Alpha Centauri star system are still burning, our Alpha Centauri will have only been a shooting star. Because the outcome was inevitable. The youngest members of the group were graduating from high school in the spring of 1976, and our paths were about to become separated. Bruno Névez was going, for example, to enroll in a musicology course at the University of Western Brittany. For my part, it was at this time that I left the band and resumed my solo career for a regional tour that would last throughout the summer of 1976. However, the links were not broken because the following October I performed on a regional tour as the opening act for the singer Georges Chelon. Bruno accompanied me there on the guitar. I think there was a desire by Bruno to keep track of what we had done together. This resulted in the Alpha Centaury album, recorded in a short time due to various constraints.

“Many of us read science fiction”

What was the inspiration behind the name of the Alpha Centauri group?

As I said, the choice of this name belongs to one or the other of the Névez brothers (or presumably to both). They always told me that it was a symbol: Alpha Centauri being the closest star to our sun. Both the closest but also so far away. A symbol of the relativity of things in a way. In fact, since that time, I realized that Alpha Centauri was a three-star system and that Alpha Centauri C, which is called Proxima Centauri, should, according to their logic, have given the group its name. But it didn’t really matter. The period was favorable to these kinds of names. Man had walked on the Moon in 1969. Many of us read science fiction. For my part, the astro-physicist-writer Isaac Asimov particularly fascinated me. Finally, in the bar of our small Breton town of Landerneau where we met every evening, the singer Gerard Manset was looping on the jukebox. Gerard Manset had released in 1970 an LP that became a cult: “La Mort D’Orion,” an album ranked by Rolling Stone magazine as the 56th best French rock album. A tribute record to a constellation.

Why was the vowel I replaced by Y in the album title? Was this decision influenced by the previous release in 1971 of Tangerine Dream’s album of the same title? It seems that the name was fashionable in the 70s, since there is also a Canadian prog band of the same name who released an album in 1977 and a French free jazz band called Alpha du Centaure who released their album in 1979.

I think that it is quite stupidly an involuntary shell of the graphic designer. Maybe Yannick Sivienne, the graphic designer, had listened to Tangerine Dream? I’m afraid he had never listened to our music. In any case, I think that given the urgency in which the record was apparently realized, it should not have seemed possible to ask a volunteer to start the cover design anew. And then, after all, why wouldn’t the Alpha Centauri band have called their album Alpha Centaury? Moreover, when Bruno couldn’t find a title for an instrumental piece, he called it ‘Nameless’.

How long did it take you to compose your album? Give us more details about the recording sessions of the album: where, when, and any event/incident worthy of mention during the recordings.

The album is the result of a choice among the titles that we took about a year and a half to compose, rehearse, and sometimes – but rarely – play on stage. It is likely that the album was made in a few takes. None of us had money and therefore could not afford to linger in the studio. For the same reasons, the disc was recorded in the studio closest to the city where we lived, a few kilometers away. It seems to me that at the time it was the only studio in the region.

Please elaborate on the main themes of the song lyrics. What were the main sources of inspiration?

There are two ways of composition in this album: the lyrics that I put on music pre-written by Bruno (Cages en Béton, La montre) and the music that Bruno and Serge put on texts that I wrote (Le rire des pierres, Passant de la nuit). Cages en Béton is an environmentalist song, written at a time when I probably didn’t even know the word ecology. It speaks against excessive concretization. A fight that I continue until today from within several associations. The time was that of the return to the earth. The year after the record, I lived in a farm house and I cultivated a small vegetable garden. Le rire des pierresis a cry of sadness and anger. A lot of young people in our area were killing themselves in car accidents. They were often intoxicated and engaged in suicidal driving behaviors. One of our friends had died a few days after getting her driver’s license.

Passant de la nuit is a dreamlike text. I was very interested in Dadaists and surrealists and like them, practiced automatic writing from time to time. The song is very visual. A few years later, I would probably have made a painting of it.

Finally, La montrespeaks of the passage of time, not in a linear way as rationality would have it, but as an emotional experience, with its unexpected changes of tempo. Bruno’s music with its rhythmic breaks is perfectly in tune with the text.The song is about the “counted hours”. This is the last song I wrote for the record and, subconsciously, we probably knew that the hours that the band had left to live were numbered.

Please elaborate on the main themes of the song lyrics. What were the main sources of inspiration?

There are two ways of composition in this album: the lyrics that I put on music pre-written by Bruno (‘Cages en Béton,’ ‘La montre’) and the music that Bruno and Serge put on texts that I wrote (‘Le rire des pierres,’ ‘Passant de la nuit’). ‘Cages en Béton’ is an environmentalist song, written at a time when I probably didn’t even know the word ecology. It speaks against excessive concretization, a fight that I continue until today within several associations. The time was that of the return to the earth. The year after the record, I lived in a farmhouse and I cultivated a small vegetable garden. ‘Le rire des pierres’ is a cry of sadness and anger. Many young people in our area were killing themselves in car accidents. They were often intoxicated and engaged in suicidal driving behaviors. One of our friends had died a few days after getting her driver’s license.

‘Passant de la nuit’ is a dreamlike text. I was very interested in Dadaists and surrealists and like them, practiced automatic writing from time to time. The song is very visual. A few years later, I would probably have made a painting of it.

Finally, ‘La montre’ speaks of the passage of time, not in a linear way as rationality would have it, but as an emotional experience, with its unexpected changes of tempo. Bruno’s music with its rhythmic breaks is perfectly in tune with the text. The song is about the “counted hours.” This is the last song I wrote for the record, and subconsciously, we probably knew that the hours that the band had left to live were numbered.

Your album was released in 1976, during the heyday of French progressive rock. What is the reason why it was released independently? Did you circulate demos to majors or labels specializing in progressive rock before making the decision to proceed with a private pressing?

The answer to this question is contained in my previous answers: an ephemeral band, a record recorded in the urgency of an inevitable dislocation. But also, a total lack of means and an almost complete lack of knowledge about how the music industry works. At the end of adolescence, in the depths of our native Brittany, no one had told us about majors or labels. And if this had been the case, they would have seemed to us as distant as the Alpha Centauri star system. To use a reference cited above, in 1976, Gerard Manset was 31 years old, Bruno was 18. We weren’t playing in the big leagues yet.

There is practically no information about the band in the contemporary French music press, even though your album became an important collector’s item over the years. Did you intentionally refrain from publicity or was there not enough interest from the press?

The record was recorded for the sole purpose of leaving a testament of our creations, but in very few copies and without any professional communication or distribution. After its release, the group disappeared. No one was there to defend this vinyl anymore. We all had embarked on other pursuits already. In reality, this album was a kind of bottle thrown into the sea with the message: “remember that we existed”. Fortunately, the bottle was found on other shores, often far away, and from time to time the disc has been reborn, reissued, sometimes broadcast on the net too. ‘Reborn’ was also the title of one of the last songs I wrote with Bruno.

“To be reborn a new day from an eternal childhood

Childhood has confessions that are not yours

You see the past again, you see the path again

And childhood is no more, but the absence is so beautiful.

Is this a lifelong dream that you hold in your hands?”

Too bad it’s not on the album.

Very little is known about the band’s live performances. Did you play live? If so, in which venues and which other bands were on the same bill?

There were very few live performances. There are many reasons for this. The main activity of the other musicians was studying in high school, aiming at graduating before considering higher studies. I was actually the only “professional” in the group. A professional who, I admit, had a hard time making a living. None of us had a driver’s license, hence the impossibility of playing at distant venues. We depended on the few friends who had a vehicle. As a result, the few concerts we gave took place in small venues in the nearby region with a limited audience. We didn’t even bother to inform the journalists. The owners of concert cafes or the managers of the youth centers who welcomed us were content with word of mouth or a few posters. We were really a very localized amateur group. Hence a surprise on my part about the interest that this record of teenagers still arouses today.

What other contemporary bands can you name as partners/friends of the band?

We mainly socialized with local groups. I remember one of them called successively: Trium Thanatos, Exodus, and Midnight 13. I don’t know if they changed musicians as often as their name, but our drummer Daniel Abhervé also played with them occasionally.

What did the band members do after disbanding? Can you give us a brief description of each member’s career after Alpha Centauri (including yourself)?

I will only be able to provide information, possibly incomplete, about Bruno. However, his significant career as a musician, arranger, composer, and instrumentalist, recognized by his peers and specialized journalists, will assist me. As for Daniel Abhervé, as mentioned, he continued to play with various bands in the region, but without this evolving into a full-fledged professional activity. A friend encountered him a few years ago working as a waiter in a restaurant. Daniel passed away in 2020. Serge Névez disappeared. Although I was in touch with him on social networks about ten years ago, he no longer communicates through this medium. Some refer to him as a “hermit” withdrawn from the world.

Now, let’s discuss Bruno. In 1976, after the record and the tour during which he accompanied me, Bruno Névez studied musicology in Brest, where he was particularly noticed by his harmony teacher. Upon completing his studies, he gained recognition as an arranger for some singers in the region, as well as a jazz musician. He performed alongside renowned musicians such as Eric Barret (saxophone) and Richard del Fra (double bass), but primarily with his close friends: Jacques Pellen, Gildas Boclé, Didier Squiban, Patrick Péron, Peter Gritz, and Jacky “Blet” Thomas, with whom he formed various band configurations. Journalists in the 90s praised his originality, technique, and hailed him as a significant figure in international jazz. However, Bruno never seriously considered moving away from his native region. When asked by journalists why, he didn’t have a definitive answer.

His career came to an end a few years ago. Stricken with a brain tumor, Bruno became hemiplegic. Despite this, he had a custom-made guitar that allowed him to express himself with his left hand only. Sadly, he passed away on February 15, 2024.

As for me, after 1976, I continued my singing career, often performing solo on stage with my guitar, sometimes accompanied by a few musicians. My artistic activities diversified: I worked as a comedian, radio host, and press cartoonist. In the mid-80s, I worked in a theater and participated in the creation of several festivals, including jazz, street theater, and cinema. In 1988, I joined the Ministry of Culture, where I directed the training department of the Louvre Museum for 12 years. Additionally, I chaired the staff association of the establishment, allowing me to pursue cultural programming activities.

In 2000, I took over the management of the new performance hall of the National Museum of Asian Arts – Guimet, a magnificent 300-seat theater where I invited thousands of artists from Asia over 17 years: musicians, dancers, actors, and more. The program included a mix of arts from the oldest traditions, especially improvised music, along with the most innovative contemporary experiences. An important part was devoted to the process of inter-community fusion. For my last three years at the Ministry, I joined the Orsay and Orangerie museums, where I continued my programming activities.

Since retiring in 2020, I have continued my freelance career, leveraging my Asian networks.

The underground of one era often becomes the mainstream of another. Nowadays, with numerous waves of prog and psychedelic music following the golden age of the 60s and 70s, how would you position your first recordings?

I must admit, it’s challenging for me to answer this question. My influences were more literary than musical, and the singers who inspired me at the time included Claude Nougaro (on the jazz side) and Leo Ferré (on the classical side), among many others. On the other hand, I know that Bruno and Serge regularly listened to bands like Genesis, Pink Floyd, and Ange. However, we all diverged into different musical directions. Bruno delved into jazz, while I explored Asian music, especially classical and contemporary improvised music, although I didn’t actively practice them. It doesn’t seem that the other musicians have produced anything resembling what is called prog today. In fact, we weren’t even aware of belonging to a particular musical genre. What perhaps makes this record unique is the unexpected complementarity of individuals who didn’t come together under any specific banner, didn’t necessarily share the same influences, but managed to collaborate. It was the chance of an encounter. We were labeled much later.

George Rossolatos

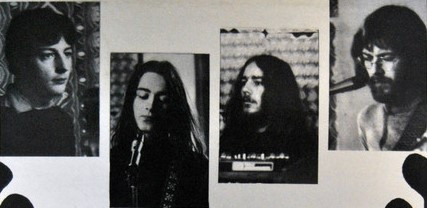

Headline photo: Bruno Névez and Hubert Laot of Alpha Centauri

PQR-Disques plusqueréel Official Website / Facebook / Shop / Bandcamp / YouTube

Thank you so much for this kind dedication; the name “Alpha centauri” was suggested by Marc Nevez, our oldest brother.