Chuck Kirkpatrick | Interview | “I engineered Clapton’s ‘Layla’ album”

Chuck Kirkpatrick, an esteemed musician, engineer, and producer, has carved out a remarkable career spanning several decades, leaving an indelible mark on the music industry.

He initially gained recognition as a guitarist and vocalist with the band Game, celebrated for their albums such as ‘Game’ and ‘Long Hot Summer’. Chuck’s engineering expertise extends beyond his band’s discography, with significant contributions to various artists’ albums. His legacy also includes his pivotal role as a studio engineer at Criteria Studios in Miami, where he worked on iconic albums for renowned artists like Eric Clapton, Aretha Franklin, and The Allman Brothers Band. Chuck’s diverse skill set and unwavering passion for music have left an indelible mark on both the studio scene and the broader landscape of popular music.

“Game’s reputation was primarily built on live performances”

Looking back, you had a truly remarkable music career. Would it be possible to pinpoint a certain period you enjoyed the most? Was it the early start of playing with bands or later on?

Chuck Kirkpatrick: Over a span of nearly 65 years, it’s challenging to pinpoint any single most enjoyable period. There were many enjoyable moments, but they were accompanied by negative experiences that, thankfully, have mostly faded from memory. One of the most exciting periods occurred in the mid-eighties. During this time, I toured with Firefall and simultaneously made appearances on the TV show Star Search with a band called Windstar. When in town, I also relished participating in numerous recording sessions as a singer and guitarist and performing at local gigs on the weekends. However, this vibrant period abruptly ended in August of 1986 when I was shot during an attempted robbery. Hospitalized for three weeks, I was effectively sidelined for months afterward. With unwavering support from family and friends, along with extensive physical therapy, I eventually managed to resume my busy schedule.

In 2014, I joined a highly successful Eagles tribute band, touring the country and playing concert venues as well as cruise ships. I was making four to five times the amount of money that I was used to making in nightclubs. Sadly, personal differences and internal problems led to my departure from that band. Shortly thereafter, I joined a successful Fleetwood Mac tribute band, only for the bandleader to disappear, leaving the rest of us owed money. I attempted to start another Fleetwood Mac tribute band, but after just one performance, the group disbanded.

One of the earliest bands that recorded material was called The Aerovons. What initiated you guys to start playing? Was there a certain moment in your life when you knew you wanted to become a musician?

I started playing guitar in 1957. The first band I joined was in 1959 called Bobby Naylor and The Saints. We played around 8 gigs over the course of a year or so. After that, I joined a group called The Eldoradoes, which lasted a little over a year, probably playing less than 5 gigs—hard to remember now. In 1962, I joined The Impalas, and that band lasted a little over two years. All of this was before The Beatles. While still in high school, playing in bands was something I assumed I’d have to give up when I started college. Back then, the best a local band could hope for was to land a steady job in a bar or nightclub. That changed in early February 1964 when The Beatles appeared on the Ed Sullivan show, galvanizing the world forever. The bass player in The Impalas and I went to see A Hard Day’s Night together. When we left the theater after that movie, we were both in shock, hardly speaking a word nearly all the way home. That was the defining moment for me and millions of other musicians, most of whom would not be professional musicians today. Of course, my parents had their plans for me to become an electrical engineer with a college degree and a real future, not one in the music business.

I have been very fortunate to have remained in this business my entire life, surviving because I was able to work during the day in jobs connected to music and perform at night. Since 1966, I have been a recording engineer and producer. I worked at Criteria Studios from 1966 to 1972, and again from 1979 to 1982. From 1989 to 1994, I worked at a jingle production company. Subsequently, I operated my own production business from 1995 to 2005. Following that, I worked for a major ad agency production house from 2005 to 2015. To this day, I continue to produce jingles and provide voiceovers for radio spots from my home studio.

In late 1964, I departed from The Impalas and joined “The Aerovons,” a band with the most mispronounced, misspelled, and misunderstood name imaginable! Initially, we followed the trend of many local bands at the time, striving to imitate The Beatles. We even had custom-made “Chesterfield” suits and performed about 90% of our shows with Beatles songs. However, everything changed overnight when we decided to transition into a Beach Boys tribute band. Out went the suits, replaced by white pants and striped shirts! We quickly gained popularity locally and secured the coveted position of house band for a large teen dance club in Fort Lauderdale named Winterhurst. Interestingly, Winterhurst had previously been an ice skating rink, which failed once the novelty wore off. Despite the owners’ efforts to make their new venture successful, it eventually closed due to financial issues. Months later, the club reopened under new management as “Code 1” and successfully hosted national acts such as The Beach Boys, Sonny and Cher, The Who, and The Association. The Aerovons disbanded at the end of the summer in 1965 when our bass player, Dennis Williams, left to attend Notre Dame.

How did Proctor Amusement Co. come about?

After The Aerovons disbanded, I joined an already well-known and popular local group called Gas Company. They were a quartet, performing at numerous local teen dances and showcasing considerable talent. However, they aimed to enhance their vocal harmony capabilities.

Aware of my reputation for vocal arranging and knowledge of harmony, Gas Company invited me to join as a fifth member. Together, we secured a singles record deal with a local label and entered the studio to record a song that eventually made it onto the Billboard Hot 100 list. However, we encountered a problem with the name. Another band in the U.S. already held exclusive legal rights to it. Consequently, we changed our name to Proctor Amusement Company. Under this new name, our band flourished throughout Florida, establishing ourselves as unrivaled vocal harmony performers. We covered songs by the likes of the Association, Beach Boys, Four Seasons, and even the Four Freshmen. Our popularity soared, especially among high school prom organizers, drawn to our matching suits and clean-cut appearance. Our vocal capabilities were further enhanced when we welcomed a sixth member as our front-man and lead singer.

It must have been great to have your brother behind the drums?

To this day, I maintain that my brother is the greatest drummer I have ever played with. Sadly, we live on opposite coasts and have not regularly played together in over 40 years. However, we have reunited for special occasions, most recently for a 50-year reunion of our band Game. Scott has an extensive resume, having toured and recorded with numerous artists including Firefall, the Byrds, Jaco Pastorius, Coco Montoya, and Aerosmith, among others.

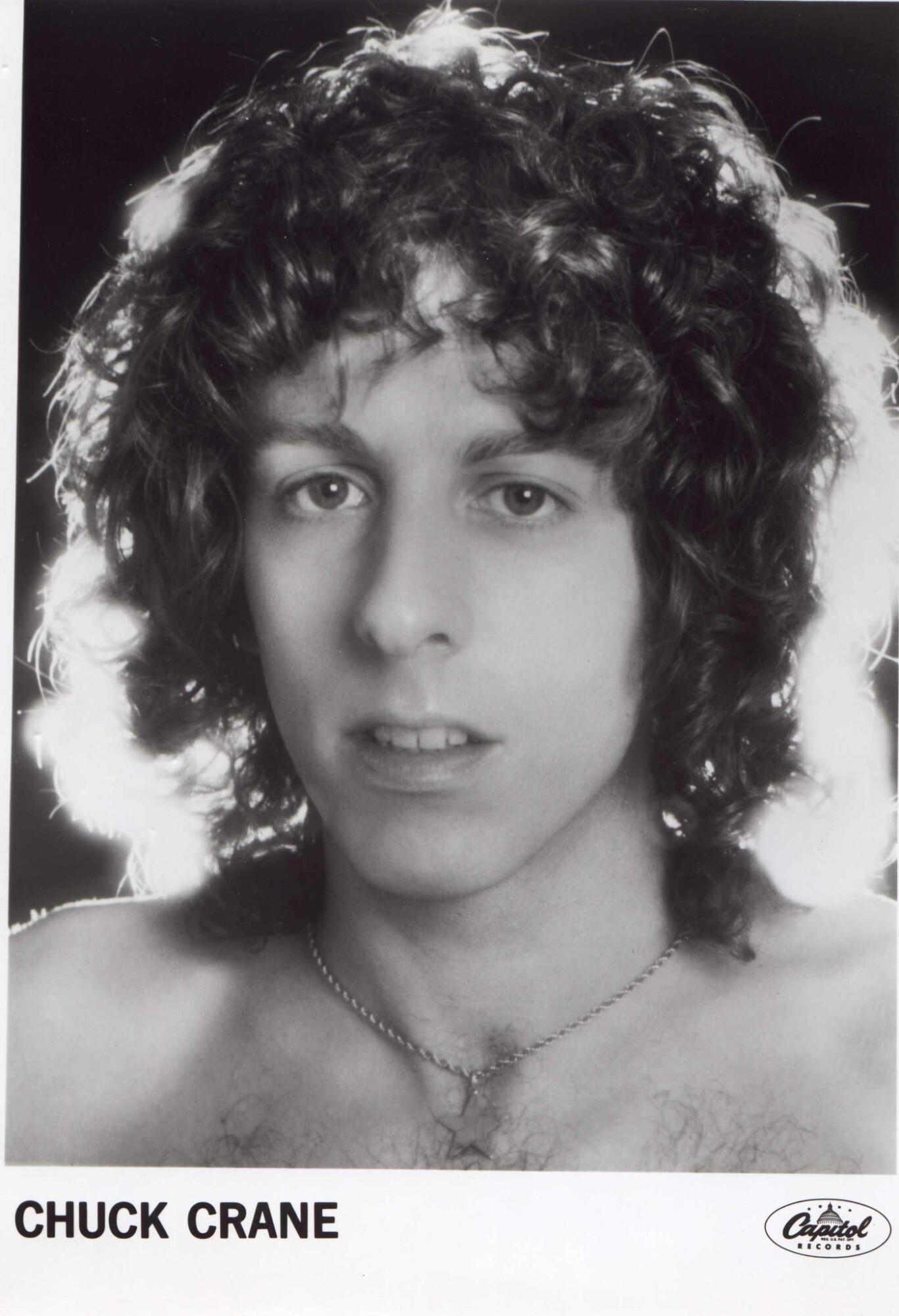

Scott also contributed drums to my 1978 Capitol album, ‘Crane,’ and has continued to collaborate on many of my recordings since then. Thanks to modern technology, Scott is able to record drums in his own studio located 3000 miles away! Additionally, he has written and produced four solo albums, which are regularly aired on internet “Trop-Rock” stations.

“Our song list now featured Hendrix, Clapton, and a range of harder rock songs”

Would love it if you could tell us about some venues you played? What bands did you share stages with and what eventually led you to change the name to Game?

While Proctor Amusement Company was enjoying success and continuous bookings primarily as a cover band, we began to develop our own style and write our own songs. We were incredibly fortunate to have Criteria Studios as our playground and classroom, thanks to my employment there and having keys to the place. When we weren’t rehearsing in our warehouse in Fort Lauderdale, we were either playing or recording in the studio during its available time slots. Gradually, we started to establish a true identity as a band, yet we never felt entirely confident until one afternoon at Criteria Studios while rehearsing a new original song. As we began to jam, an electrifying energy swept through all of us, igniting a spark of inspiration. It’s difficult to articulate that feeling, but the energy between us surged, and we practically exploded within that studio space. When the song finally concluded, we were left speechless. In that moment, we realized our potential and understood what we were truly capable of.

When the fall prom season arrived and the bookings poured in, we resumed our regular shows. However, we had grown weary of performing for unresponsive and often inebriated high-schoolers. After a particularly disheartening night at a prom, where drunken attendees were vomiting on the dance floor and paying little attention to our performance, we reached a breaking point. Back in our hotel room, we made a firm decision to reinvent ourselves as a genuine band with our own identity and original material. Our first order of business was a name change; we became “Game.” However, our new stage appearance didn’t sit well with the adults who booked us for proms. Gone were the coats and ties, replaced by mismatched tie-dyed T-shirts and bell-bottom jeans. Our repertoire underwent a significant transformation as well. While we still excelled at harmonies, our song list now featured Hendrix, Clapton, and a range of harder rock songs. We played with increased volume, energy, and at times even insulted unresponsive audiences.

As for the transition from “Proctor Amusement Company” to “Game,” as mentioned earlier, it stemmed from our desire to shed associations with a band perceived as lightweight and pop-oriented. We aimed to adopt a more progressive and rock-oriented identity.

During our time as P.A.C., we performed at various teen clubs and dances along both the east and west coasts of Florida. As Game’s reputation and popularity soared, we secured opening act slots for renowned artists such as B.B. King, Poco, Ike & Tina Turner, Van Morrison, Janis Joplin, The Allman Brothers, Ten Years After, Rare Earth, and the New York Rock and Roll Ensemble, among others. Our performances took us to major concert venues including the Sportatorium, Miami Jai-Alai, Marine Stadium, and Roberts Sports Arena in Sarasota. Eventually, we headlined our own shows across Florida. Notably, we performed six shows in Sarasota within a year, during which our song ‘Fat Mama’ held the number one spot on the charts for two weeks.

What were the circumstances of signing with Faithful Virtue Records to record your debut album in 1969?

Well, this could be a long one! As I’d previously mentioned, we were constantly recording and rehearsing at Criteria Studio and writing our own stuff. We had worked for about 6 months on an album which I refer to as the “Experimental” album. The songs were quite varied in style; some fairly hard-rocking and others very light harmony-based ones. I basically produced and engineered the entire thing and I really thought we had something. When it was finished, our then-manager took the finished album to New York to shop it for a record deal which I was convinced we would get easily. After nearly a week of pounding on record company doors, our manager called me at the studio to tell me that everyone had “passed” on the album. I was in total shock. I got up off the couch where I’d been sitting, went straight for the front door, stiff-arming it open with a bang, and began walking up 149th street crying my eyes out. My boss and owner of the studio, Mack Emerson – God bless him – came after me in his car. He’d been witness to the work I had put into that album and happened to be in the lobby where I was when the fateful call came. “Get in the car,” he yelled to me as I continued to walk. “Come on, let’s go to lunch and talk about it…..”. Mack was like a second father to me and I owe my career to him. Mack was also a former musician and well understood the nature and disappointments that are all part of this business. Mack managed to calm me down, praising my work and encouraging me to keep trying.

When our manager returned to Florida, he brought along what would eventually lead to us getting a record deal: six songs in demo form by songwriters Bonner and Gordon, two guys who had a track record as hit songwriters. Faithful Virtue was one label our manager had visited and played our stuff. They were tremendously impressed with the production but felt that the songs weren’t strong enough. “Let’s see what your band can do with these…”, the Bonner and Gordon demos. When we first listened to them, we thought the songs were absolute crap, only because the demos were so bare-bones, basic recordings. Our manager encouraged us to produce these songs as we would our own. Our pent-up frustration and anger at being turned down made us take the attitude, “We’ll show THEM!,” and we dove into recording all six of these songs in a stunning fashion that got us immediately signed by Faithful Virtue. We took six crappy sounding demos and made masterpieces of them, three of which were released as singles: ‘When Love Begins to Look Like You,’ ‘Julie,’ and ‘Goodbye Surprise’. They even released one of my songs that had been on the experimental album called ‘My Kind of Morning,’ a very Carpenters/5th Dimension-like pop song. None of the singles broke the charts, but the production convinced the label that we were capable of making a good record.

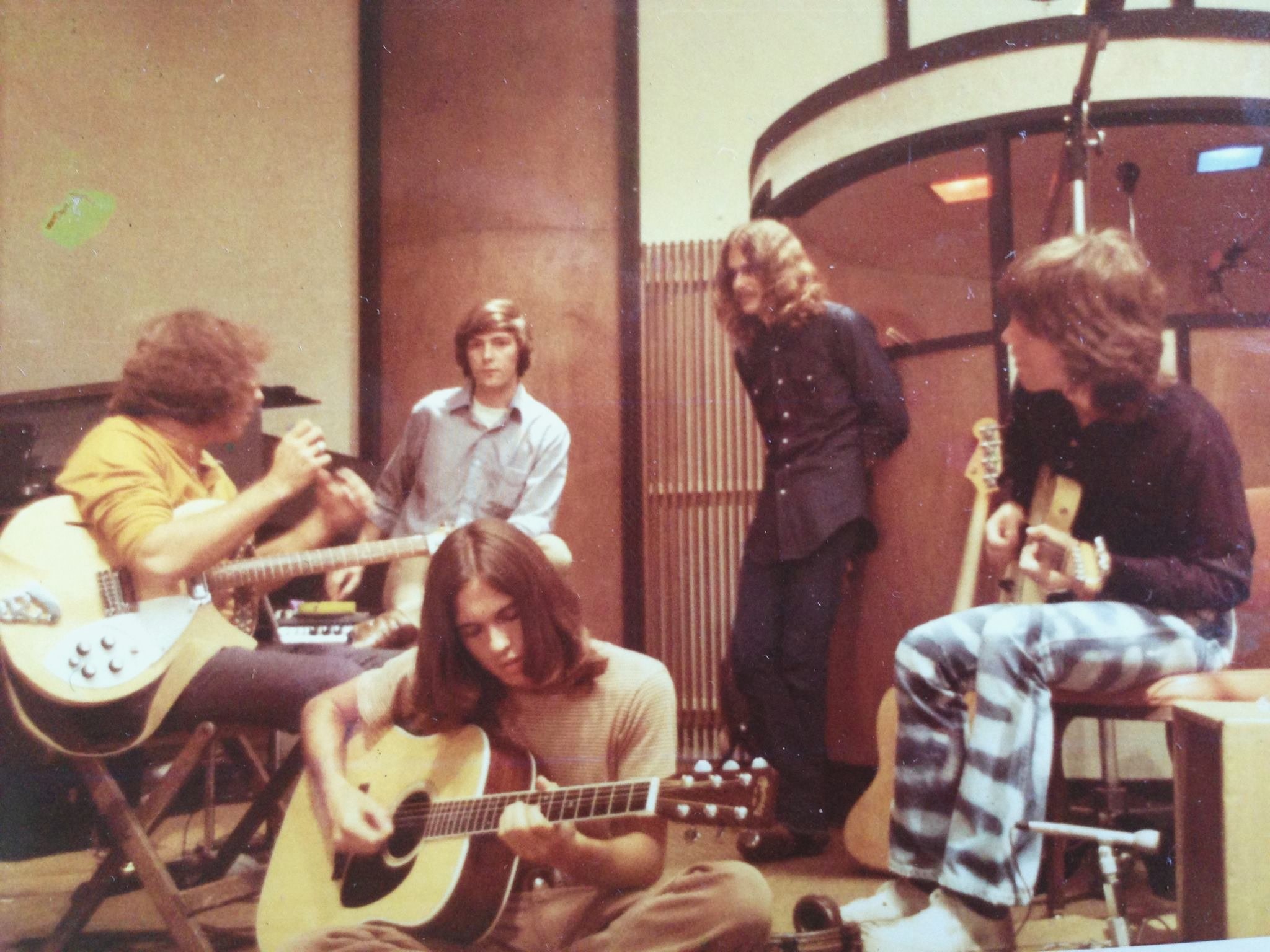

We began recording our first album for the label in early 1970. It was simply titled “Game” with a Pieter Bruegel painting as the cover art.

Tell us about the studio and your gear?

At the time, Criteria had only a one-inch 8-track tape machine. We were using a 3M tape machine, the same type famously dubbed ‘Jaws’ by Fleetwood Mac when it “munched” one of their master tapes during the recording of their first album with Lindsey and Stevie. Our 3M machine also took a bite of one of our tapes. While the design of the machine’s transport was revolutionary, it still had some “bugs.” We primarily recorded in Criteria’s Studio A, the “big room” (40 x 80 feet), using a custom-built Jeep Harned 16-input, 4-channel console that I had modified to 8 channels using a simple design. We recorded our tracks mostly “live” – all of us playing together in the room. Overdubs were minimal, limited to solos and “repairs.” Vocals, of course, were overdubbed, including the lush background harmonies we had become known for. In those days, there was no automation of recording consoles, so every adjustment during mixing had to be made manually and repeated each time the song was played through. This involved moving 8 different volume controls, or “faders,” sometimes simultaneously, which was nearly impossible for a single engineer. We mixed with each band member assigned to a fader and a cue list instructing when to move and by how much.

What was the songwriting process like in the Game? What do you recall from the session you had in the studio?

Eddie Keating and Les Luhring wrote about 75% of the first album material. If I remember correctly, they both came in with finished or partially finished lyrics and would play the song for the rest of us on their respective instruments. We would then start constructing a good rhythm track. George Terry, Scott, and I contributed a bit more to the ‘Long Hot Summer’ album. There were a couple of occasions, one in particular, where we would jam on a riff or chord progression, and then write lyrics to it afterwards. ‘Exit’ on our first album is an example. I started playing a rhythm guitar part and the rest of the guys fell in around me. Eddie took the track home and wrote lyrics to it.

The album itself sounds like it would be made five years later. What was the overall vision you had when album making?

I can’t really say we had any kind of vision. We just wanted to make a good record. Our first album was, for a young rock band, pretty progressive. You can hear the jazz influences all over the place; strange time signatures, tempo changes, and chord voicings beyond the usual triad structure….that, and our harmonies. Vocally, there’s never been a band around these parts that equaled what we did to this day.

There was a definite cohesiveness to the first album that was somewhat lacking on ‘Long Hot Summer,’ probably because of the variety and different styles of writing we had as individuals, and the fact that each writer had more of a preconceived idea of how the end result should be on his particular song. Not that there weren’t some great songs on ‘Long Hot Summer’. Writing-wise, I believe it was a far better album but it just didn’t have the same conceptual feel as the first.

Did you do a lot of shows after the album was released? Did you get any press and airplay?

I would say that the breakthrough for us was the song ‘Fat Mama’ receiving significant airplay and reaching #1 in Sarasota. Oddly enough, the single only sold 17 copies there! Game’s reputation was primarily built on live performances. Securing any kind of airplay was challenging for a local band back then, and it was crucial for generating sales. Our significant break came when the prominent local rock stations began playing ‘Sunshine 79,’ written by Scott. I believe that the inclusion of Miami in the song’s storyline endeared it to the stations, and the subsequent airplay generated a lot of interest in the band. We started opening shows for well-known acts, and there were occasions when we performed so well and with such intensity that the headliners struggled to follow us! As a result, we received considerable local press coverage after some of these shows.

‘Long Hot Summer’ was followed on Evolution Records, but your brother left before recording the album, if I’m not mistaken. Tell us about the recording of your second and sadly last album for the Game.

No, Scott participated fully in the ‘Long Hot Summer’ album and contributed probably the most-played song on it, ‘Sunshine 79’.

However, as I mentioned previously, the cohesiveness of the music was not the same, and there were personal matters affecting each of us individually, which started to impact the band. Scott remained with us for nearly a year after the album was made.

But the band kept on going until 1976?

Well, not exactly. The very last version of Game lasted well into 1979 with two Southern California members, Gilbert Gallegos – drums, and Mark Weisz – keyboards.

Scott left the band sometime around the end of 1971. It was a devastating blow to all of us because we had played with him for so many years. He and Les played little league baseball together, had their first band together, and grew up together. Scott was hands-down the best drummer in South Florida, and losing him very nearly destroyed the band. We had made plans to move to Los Angeles to try to get a record deal. We had gotten as big as we ever would in South Florida, but we simply were out of the mainstream of the record business. Scott was adamant about not leaving Florida but didn’t want to hold us back. He knew we would never go without him, and for our sake and our future, decided to leave the band. It took us several weeks to get past the initial blow of losing him, but we wanted to stay together and began auditioning drummers. Several drummers came in to play with us and knew the band was going places, but none of them were even close to Scott. We did finally find a guy named David Robinson whom we had seen playing at a local club and were quite impressed with him.

David moved to California with us, but left after a year. He was replaced by Steven Haller, the former drummer for Bo Donaldson & The Heywoods, but he only lasted a few months. Next was Dennis Fridkin, who had been with a group called “People” that had a national hit record, ‘I Love You’. Dennis stayed with us for about two years and was replaced by Phil Jones of Crabby Appleton, who had a hit record, ‘Go Back’. Phil, I might add, was the drummer on Tom Petty’s ‘Full Moon Fever’ solo album. Phil stayed with us for about a year. David Robinson returned from Florida and rejoined the band in 1976 for about a year. Both Eddie and Les became involved with other projects, and I was writing in preparation for my solo album with Capitol Records, which came out in 1978. When the album flopped, I rejoined Eddie and Les with the two new aforementioned players.

Tell us about your solo album you began working on. It was titled ‘Crane’.

After Game’s disastrous showcase performance at the Troubadour – and that’s a whole separate story – the band’s manager decided to part ways with us as a group and focus on me as a solo artist. We rented an apartment together in Santa Monica, and I began writing while my manager made appointments with record companies to showcase my work. I had one song, ‘Oh Dancer,’ which I had written back in the early ’70s, and Game had been performing it live to very receptive audiences for a couple of years.

Clive Davis of Arista Records offered me a singles deal for that song alone, but we held out for an album and long-term career prospects. Warner Brothers showed enough interest to give me $1000 to change one line in the song, but ultimately decided to pass. Ben Edmonds, a talent scout for Capitol Records, became a friend of ours, and he played a significant role in getting me in the door there. After weeks of negotiations between our lawyer and Capitol, I signed a five-year, five-album contract.

Needless to say, I was elated. Every musician’s dream and ultimate goal is to record and be distributed by a major record label, and mine had come true. I reflect on a time in my younger band days when I thought it would be cool to make a record company logo and put it in the window of my car – like I was a real recording artist! The logo I happened to choose was that of Capitol Records!

I began recording in March of 1977 at Brother Studio in Santa Monica. Brother was owned at the time by Beach Boys Dennis and Carl Wilson, and that studio just happened to be 8 blocks from where I was living at the time. Being a huge Beach Boys fan for years, I naturally wanted to record there. I flew my brother from Florida to play drums on the sessions, and I used Eddie from Game on bass guitar. We tracked four songs at Brother and five more at a studio in downtown Hollywood. I did all the guitar work, playing basic rhythm during the tracking, and then overdubbing sometimes as many as 10 additional guitar tracks.

I brought Les from Game in to help with the background vocals. The entire recording took about 5 months with some breaks in between. I began mixing in the fall of ’77 at the downtown Hollywood studio, but the sound was so bad that I scrapped all the mixes and decided to start over at Capitol’s own in-house studio. I’m very glad I did that, even at my own expense – all recording costs are charged back to the artists – because the sonic difference was well worth it.

The album was released in January of 1978 but failed to gain traction due to lack of promotion on Capitol’s part. Five months later, I received the “dear John” letter from Capitol stating that I would be dropped from the label with no renewal options.

“I engineered for Delaney & Bonnie, Allman Brothers, Petula Clark, Black Oak Arkansas, Eddie Harris, Wilson Pickett, Sam the Sham, Taj Mahal, Jesse Ed Davis, and most notably, Eric Clapton’s ‘Layla’ album”

Would be fantastic to hear about your recording engineer career. When did it first start and what are some of the first recordings you did?

When I graduated from college with an A.S. degree in electronics technology, I was hired almost immediately by a local electronics firm but never made it to my first day’s work there. During my college days, I had made a trip to Criteria Studios in Miami to gather information to write my thesis. I was in awe of all the recording equipment, and I knew then what I really wanted to be; a recording engineer. Even before I graduated, I sent an application to the owner, but I figured it was way too much of a long shot to even think about. A few days before graduation, I sent yet another letter to Criteria as a follow-up but expected no response, but a day or so before I was to begin the tech job, the call came in from Criteria. I was hired!

My position only lasted a few weeks because there simply wasn’t enough work for me to do. The owner, Mac, decided I would be more valuable working up in Fort Lauderdale at a place where his new recording console was being custom built by a fellow named “Jeep.” I worked there for nearly a year, helping to wire the new console, which was an invaluable experience in learning its real workings. One day, I got a call from Mack at Jeep’s place, saying he needed me back down at the studio because one of his chief engineers had just quit. That was my big break. Almost immediately, I was sitting behind the big console, learning as I went and conducting actual sessions as a senior engineer. One of the first big sessions I did was James Brown’s ‘Give It Up Or Turn It A-Loose’.

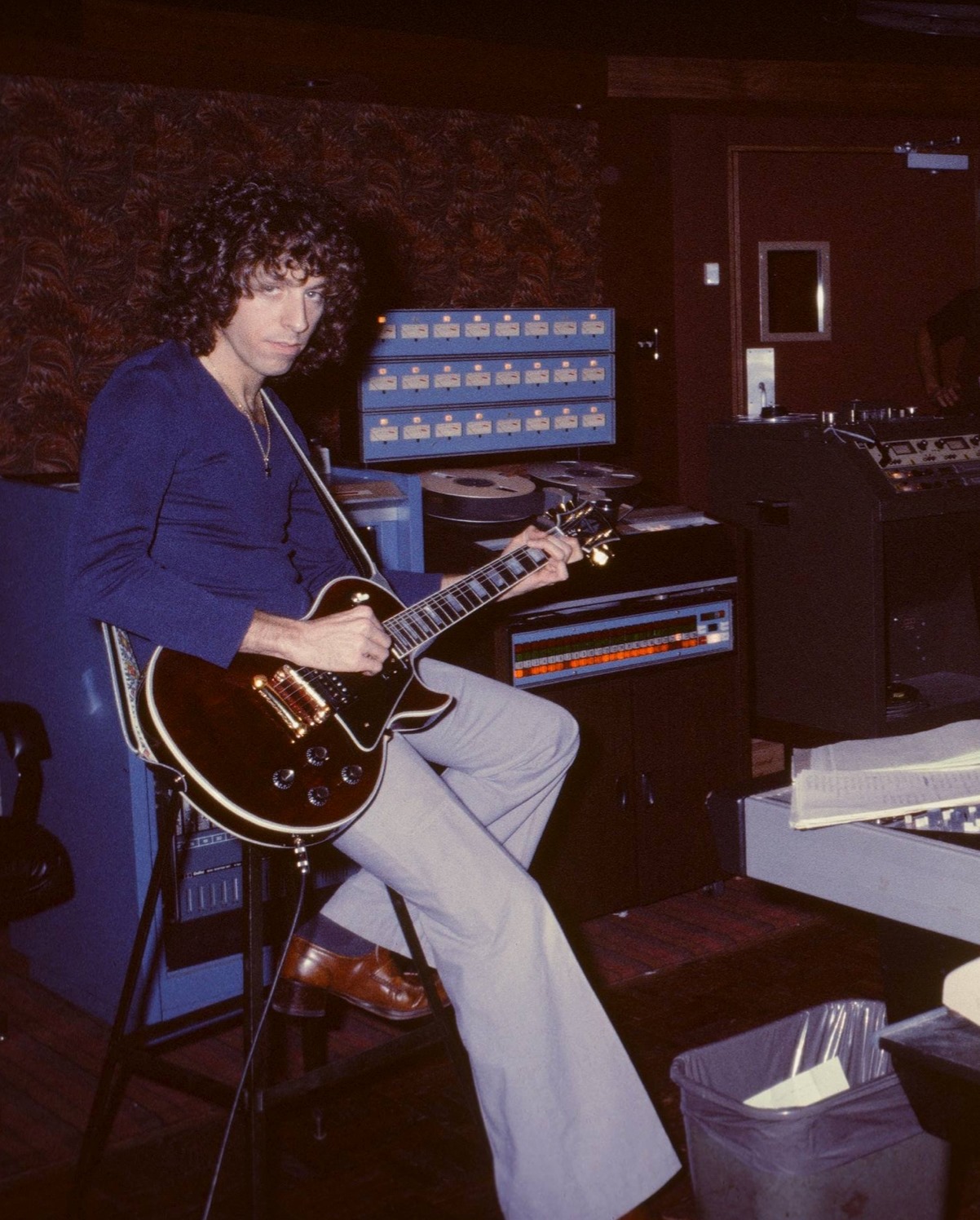

The first couple of years back at Criteria, business was mostly local stuff – jingles, local bands, and singers – and there were maybe two or three sessions a week tops. All that changed when Atlantic Records moved in and brought almost their entire roster of artists to record there. I got my first gold record for engineering Brook Benton’s ‘Rainy Night In Georgia’. My next was for Aretha Franklin’s ‘Don’t Play That Song’. Over the next two years, I engineered for Delaney & Bonnie, Allman Brothers, Petula Clark, Black Oak Arkansas, Eddie Harris, Wilson Pickett, Sam the Sham, Taj Mahal, Jesse Ed Davis, and most notably, Eric Clapton’s ‘Layla’ album. The studio was going 24 hours a day, with me pulling 18-hour days, doing two to three sessions a day, all while I was rehearsing and playing with Game!

Probably my most exciting session was when I was hired to record the group “America” over at Abbey Road Studios in London. I was the engineer on four songs from their album ‘View From The Ground,’ which included the hit single ‘You Can Do Magic’ on which I also sang backup! Working in the exact same studio where The Beatles had recorded everything was a life-changing experience for me.

What makes a good engineer?

This will be very simple and very short: ears. George Martin’s book is entitled “All You Need Is Ears.” Enough said. A good working knowledge of console design and signal flow is important, as well as some electronics background. But at the end of the day, all the technical education in the world won’t make a good recording if the engineer cannot hear properly or discern what a good balance is.

When did you begin working as a session singer and guitarist…

One of the huge advantages I had as a studio employee was being “in the right place at the right time” when a client suddenly decided that their recording needed an additional or different guitar or bass part. I always kept a guitar at the studio just to noodle around on during downtime, so I was ready to play when the occasion arose. When Atlantic Records moved into Criteria, I became much busier working with Tom Dowd on many sessions. Tom knew of Game and he knew I could sing and play, so he used me on several sessions with Eric Clapton, Eddie Money, and Arthur Conley. What really opened the door for me as a session singer was The Beach Boys medley I produced in 1981, which was featured nationwide on the TV show “PM Magazine.” My ability to single-handedly arrange and track multiple vocal harmony parts got me on several records, including those by Harry Chapin, Tom Chapin, America, the Bus Boys, and Jesse Ed Davis, to name a few. In 1983, I teamed up with Johnne Sambataro, lead singer for Firefall at the time, and he and I became Miami’s first-call session singers. We worked with Barry Gibb, Peter Frampton, Eric Clapton, Henry Paul, Dion, Gang of Four, and Air Supply. I’ve also done guitar and vocal work for Brian Wilson, Juice Newton, The Bee Gees, Coco Montoya, Dion, Leslie West, Michael Bolton (“Blackjack”), and Duffy Jackson, among others.

In the early 90s, studio work began to taper off. By that time, I was already working full-time as a jingle writer, producer, and announcer for a local advertising sales company.

You managed to work with artists such as the Bee Gees, Peter Frampton and Brian Wilson. What are some of the pleasant memories from working with those musicians?

One thing I’ve learned from my years of experience around musicians and artists is that the most truly talented ones are often the nicest. The Bee Gees were probably the nicest people I ever worked with. Their collective talent speaks for itself, but what truly stood out was their humility—never forgetting their roots and the journey it took to reach their level of success. Eric Clapton and Peter Frampton were also genuine gentlemen. On the other hand, there are artists whose lesser talents are often overshadowed by an overbearing presence driven by insecurity. Some of those sessions were a real challenge and generally unpleasant.

I had idolized Brian Wilson ever since I began listening to Beach Boys music in 1964. I devoured everything he said, did, or wrote. Actually getting to record with him—twice in one year—was a dream come true! Once again, it was a “right-place-right-time” situation. As I mentioned previously, I had chosen to record the “Crane” album at Brother Studios in Santa Monica, owned by The Beach Boys. Living only 8 blocks from the studio at that time, it seemed like the ideal place to record. And, of course, in the back of my mind was the thought that I might actually run into them. Sure enough, I received the call one day from the studio manager asking if I could come over right away to play guitar for Brian Wilson. Needless to say, I was there, set up, and ready to play within 15 minutes of that call. Knowing Brian’s history, I expected him to come shuffling into the studio in his bewildered manner. Instead, he sprinted across the studio, shook my hand, said, “Hi, I’m Brian Wilson,” sat down, wrote a simple little chart, and we started recording… just me on guitar, Dennis Wilson on drums, Brian on piano, and some strange fellow on acoustic guitar. The session lasted all of ten minutes—just one take—and then Brian was gone. Six months later, I received another call. This time it was James Guercio on bass, Billy Hinsche and I on guitars, and Dennis on drums. After we finished recording, Brian brought out the infamous “Fire” tapes and played them for all of us. Burins even gave me a cassette of two of his original song demos from home.

How did you get in touch with Firefall, which you became a member of from 1983 to 1987?

Firefall began losing original members one by one until the last remaining member in 1980 was lead guitarist Jock Bartley. By a previous agreement among the original band members, whoever left the band would forfeit any rights to the name and trademark. Jock became the sole owner of the name Firefall, but he had no band to tour with, so he called upon producers Ron and Howard Albert to help him find replacements. My brother and I, along with my good friend Johnne Sambataro, had done a lot of session work at Criteria with the Albert brothers, and they suggested that Jock try us out. Jock flew down to Florida to audition us, but ironically, I had been assigned to do a session with the band America over at Abbey Road Studios in London at the same time. So, I missed Jock’s audition and my chance to be in the group.

Johnne Sambataro, however, did become the new lead singer, and he and Jock decided to go ahead and begin recording the next album using studio musicians. When I returned from England to my regular job at Criteria, I was assigned to the assistant engineer position with the Albert brothers, working on the ‘Break of Dawn’ album. During the course of the recording, I was asked to add a keyboard or a vocal or guitar part, essentially playing the role of a studio musician, but not an official band member – at least not yet. Through my participation in the recording, Jock eventually realized my value as a potential band member.

“Making an album takes a lot out of you”

More solo albums followed and I would love it if you could discuss them.

More than 30 years passed after the making of my first Capitol Records solo album, ‘Crane,’ before I began a second one. With my brother Scott’s encouragement, production skills, drumming, and financial assistance, I completed my album titled ‘Keep On Walking’ in 2013. It was a collection of songs I had written between 1979 and the early 2000s. Some of the earlier written songs were recorded at Criteria, and the rest were done in my home studio.

I began working on my third album, ‘HHK III,’ in late 2015 and it was released on my 70th birthday in 2016. The bulk of the material on that album was written in the mid-2000s but there were a couple of songs I had written more than 50 years ago that were re-recorded and included.

After finishing ‘HHK III,’ I was pretty sure it would be my last, as I had exhausted most of my song catalog and didn’t feel like writing any more. Making an album takes a lot out of you.

At the end of 2018, I parted ways with a tribute band I had been a member of for the last five years, which had taken me all over the western hemisphere touring and performing on cruise ships. Being away from home a great deal of the time, I was unable to do much in the way of writing or recording. With more time to myself at home, I began going through my old catalog of music beds, looking for anything that might inspire me to write some lyrics and finish them as complete songs. Once again, there were two or three songs from decades ago that I managed to repair and re-record successfully.

During the course of making this fourth album, entitled simply ‘CK4,’ the pandemic struck the world, crippling the entertainment business and the bulk of my performing income. I was also dealing with my wife’s rapid health decline from liver failure. I managed to finish the album shortly before she died in the summer of 2020.

Needless to say, my life then changed forever. I dealt with my grief the best I could, busying myself with making improvements to my home. With most performing venues shut down due to Covid and no place to perform, I lost interest in music for a while.

When the Covid restrictions eased and performing venues began reopening, I played in a couple of Fleetwood Mac tribute bands for a while and returned to a regular performing engagement at a nearby club where I had been playing for the past several years.

In the summer of 2022, I experienced something of an emotional nature that led to the writing and completion of my fifth album, ‘V – Never Say Goodbye,’ by the end of that year. Failed romances and heartbreaks usually make for some pretty good writing, and I finished six songs in five months – all of which were about someone whom I cared deeply for but could not have.

Traditionally, I have been basically a Pop music artist, but on this album, I ventured into two different styles of music that I had never attempted before – blues and “grunge” rock. My emotions were at a peak, and I believe I delivered the vocal performance of my life on ‘This Love’ – most definitely a blues song. There are even a couple of songs on this album that might be considered “country.” With only eight original songs, which I didn’t feel were quite enough for a proper package, I included a couple of cover tunes: ‘America’ by Simon & Garfunkel and Neil Diamond’s ‘Solitary Man’.

I should mention that I have over two albums’ worth of cover songs that I have recorded in the last 20 years, but I have not released them due to the necessity of obtaining permission and dealing with clearance rights and royalties. Many of these can be heard on my SoundCloud page.

What currently occupies your life?

At age 77, I’m basically semi-retired. I don’t have to work, as I’m living off Social Security and two other union pensions from the American Federation of Musicians and the American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. Currently, I’m playing bass with a local band 10 or 12 times a month in local restaurants and nightclubs. Although I’ve mainly been a guitarist most of my life, like many others, I’ve “dabbled” with the bass guitar on and off since about 1963. I thoroughly enjoy the instrument and what it adds to the overall sound of a band. I’ve played bass on a few other artists’ recordings, and I play it on all my own stuff. I became the regular bass player for the band I’m in now about two years ago, and I think I’ve improved a bit.

The other love of my life is my miniature Schnauzer, “Julie,” my constant companion and support. I still do some radio production and jingles for a few people. Recently, I wrote and produced the new jingle for the Fayette County, Pennsylvania transportation department right from my home studio.

Another passion of mine is flying and aviation. I earned a private pilot’s license in 1975 and an instrument rating in 1983. I had about 550 hours of total time until a bad accident in 1986. I hadn’t flown since then until very recently when a good friend of mine, also a musician and pilot, invited me to fly a Honda Jet to the Bahamas.

I’m also an avid motorcyclist and enjoy daily rides on my new bike.

“There is actually quite a bit of unreleased Game material”

Is there any unreleased material by Game or any related projects?

There is actually quite a bit of unreleased Game material. Much of it is in “demo” form. There are also hours of live recordings spanning from 1968 to 1978. A great deal of unreleased stuff was done in our California studio from 1972 – 1975. A few things sound good enough to be released, which is pretty amazing given the minimal amount of equipment we had at the time. A lot of the live stuff is cover tunes, so releasing any of that would introduce licensing/clearance/publishing issues.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

That’s a tough one… mostly because after 50 years, the memory just doesn’t retain as much. Every single minute I spent in Game was great. We all got along extremely well. Our musical tastes, for the most part, were all the same. Vocal harmony-wise, we were untouchable. No other South Florida band has yet to equal what we did vocally. And aside from the harmonies, everyone in the group was a very capable lead vocalist. I’m very proud of all the songs we recorded. A lot of work went into producing each and every one. We were so fortunate to have ‘grown up’ in a major recording studio that afforded us the chance to really hear what we were doing – what worked and what didn’t as far as making a good record. We had some incredible concerts, locally and all over the state. And we were the opening act for The Allman Brothers, B.B. King, Van Morrison, Edgar Winter, Johnny Winter, Ten Years After, Ike and Tina Turner, Janis Joplin, Rare Earth, to name a few.

But the most memorable performance of all for me would have to be our reunion last summer. For years, we had talked about it, but because of personal commitments and the geographical separation – two of us being Californians – it took years to coordinate. After over 50 years of not playing together, Game came together for one night here in South Florida and played to a standing-room-only crowd of die-hard fans and friends, some of whom drove very long distances just to see this one-time event. We had two very quick rehearsals a few days before the concert, just to reacquaint ourselves with the material. I’d have to say it was one of the highlights of my life, and the band was absolutely incredible.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

I’ve been one very lucky man and musician in this lifetime. I’ve gotten breaks few ever get. I worked very, very hard at my career, and I’m proud of my accomplishments. Getting signed to a major label as a solo performer is something I still find hard to believe, short-lived as it was. No other musician friend of mine ever got that far, though Lord knows some of them should have with their talents. This business is risky. There are many shysters in it looking to take advantage of the talent who are rightfully so involved in their art that they miss the warning signs. It happened to me and will happen to almost every musician at one time or another. My favorite writer, Hunter S. Thompson, once said, “The music business is a cruel and shallow money trench, a long plastic hallway where thieves and pimps run free, and good men die like dogs. There’s also a negative side.”

I was so fortunate to have spent the better part of my career in the 60s and 70s. The business as I knew it then is long gone. I honestly don’t know how the young talent of today will survive given what’s become of the “record business.” There are no more records or tapes or CDs. Tangible media is gone. Everything is via download or streaming, and music has become “sonic wallpaper.” With their ever-present earbuds in place, people work, play, exercise, eat, even sleep to music. But they no longer really just listen. I remember the days when a new album came out and we would all gather at someone’s place to listen. With great anticipation, the shrink wrap would be removed, and this twelve-inch piece of black shiny vinyl would carefully be placed on a turntable. The needle would drop, and we would all be “transported” into another world for the next 30-40 minutes… no interruptions, no cell phones, just quiet, reverent listening.

When radio disappears, when the internet goes down, when there are no more MP3s, streaming, or downloads, all music as we now know it will be gone—except for that which is performed live. It will be akin to the situation in the 17th century when concerts were significant events—the only time anyone ever got to hear any music at all—and the music was played by real live musicians. The musicians who will survive in the future will be the ones who can take the stage with nothing but their instrument and/or voice and perform live with no gimmicks or effects—just genuine talent.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Game recording at at Criteria studio B (1970)

Chuck Kirkpatrick Facebook / SoundCloud

Love this musician.