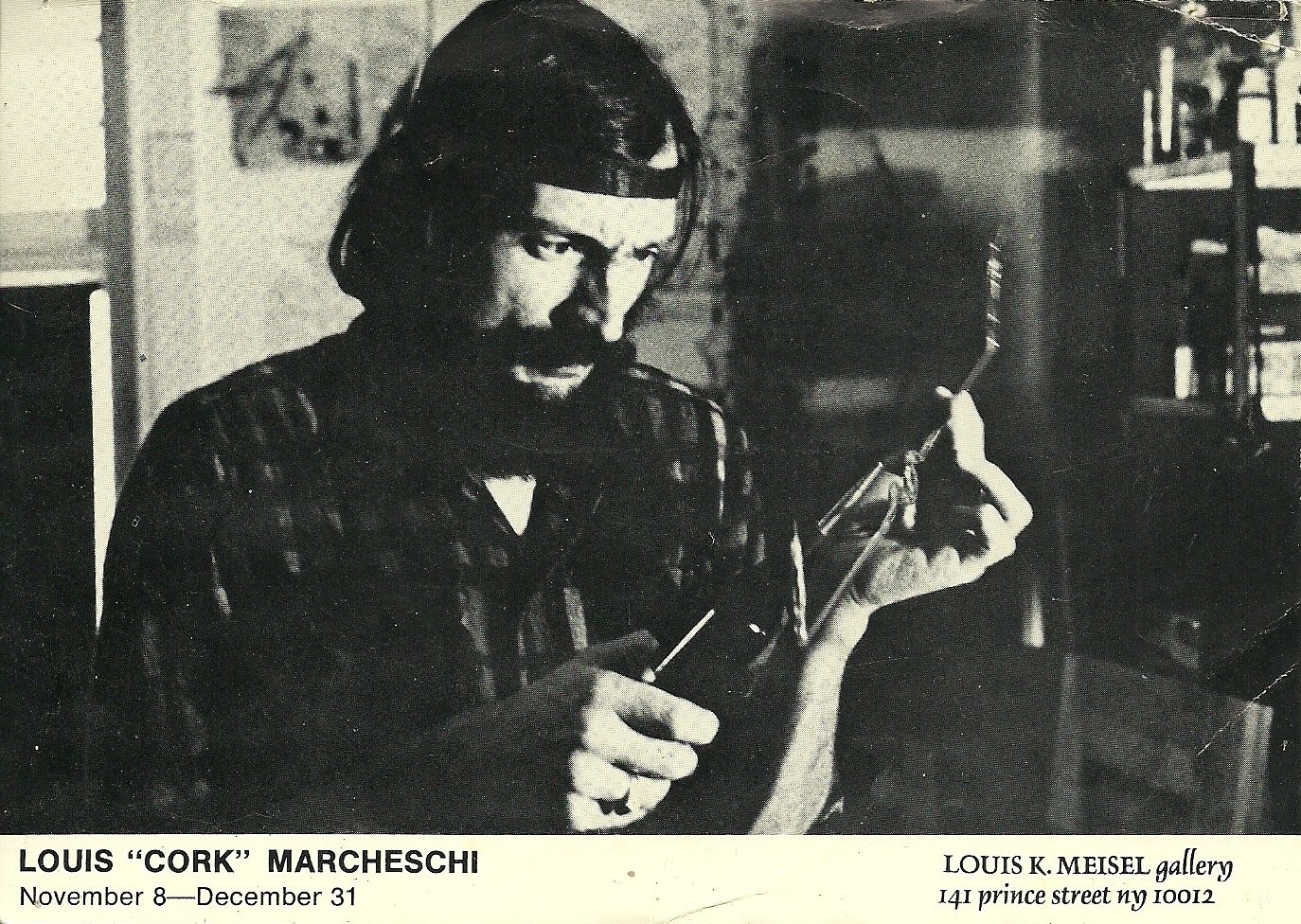

Fifty Foot Hose | Interview | The Artistic Odyssey of Cork Marcheschi

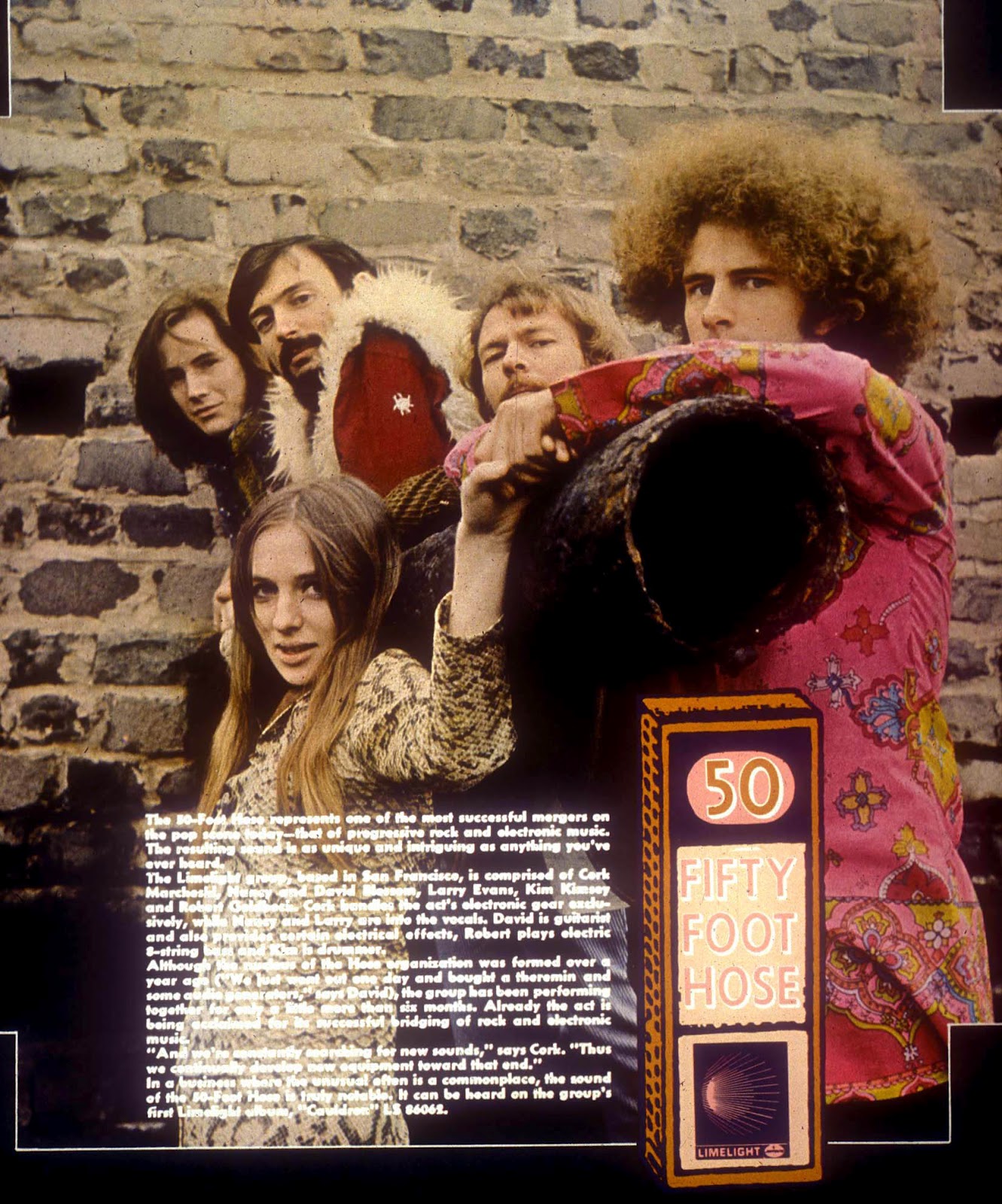

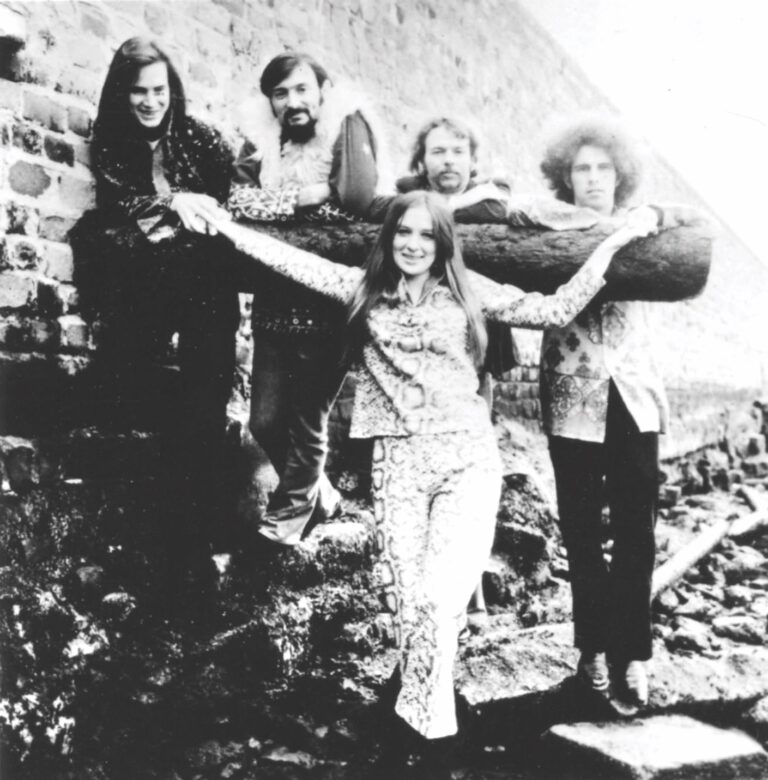

Fifty Foot Hose was an avant-garde psychedelic rock band formed in the late 1960s, known for their groundbreaking fusion of electronic music, jazz, and rock.

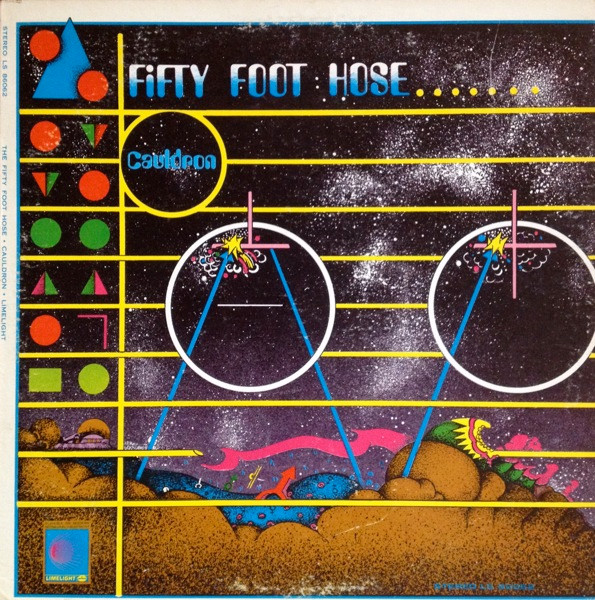

Their debut album, ‘Cauldron,’ released in 1967, remains a cult classic and a pioneering work in experimental music. Cork Marcheschi was a key member of Fifty Foot Hose, contributing as a bassist and electronic sound manipulator, shaping the band’s unique sonic landscape. His innovative use of electronic instruments and experimental techniques helped define the avant-garde sound of the band. Together, Fifty Foot Hose and Cork Marcheschi pushed the boundaries of conventional music, creating a mesmerizing and otherworldly auditory experience that continues to influence experimental musicians to this day.

“Dada has been and continues to be profoundly significant to me”

What has been your focus over the past year in terms of your artistic endeavors?

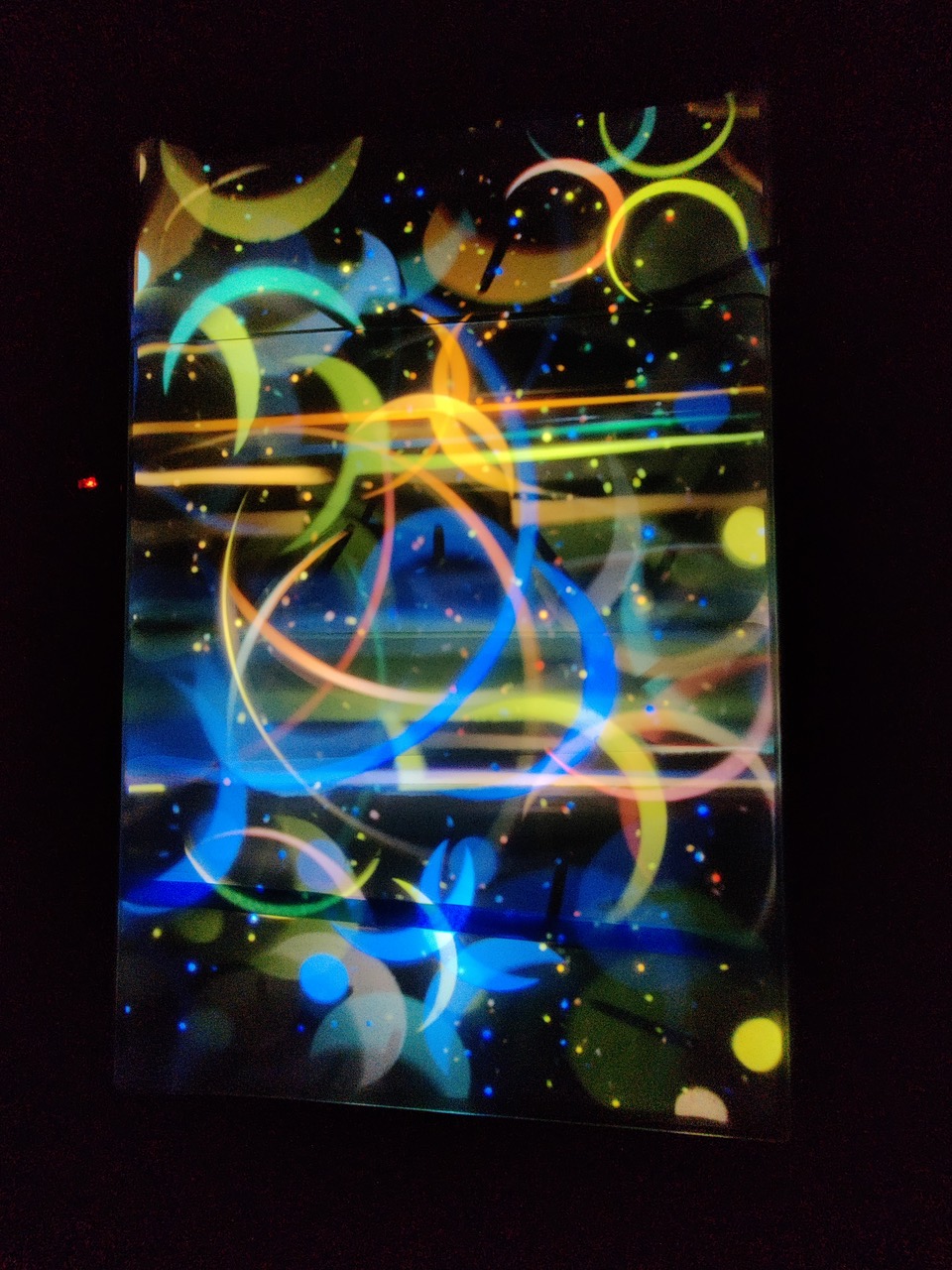

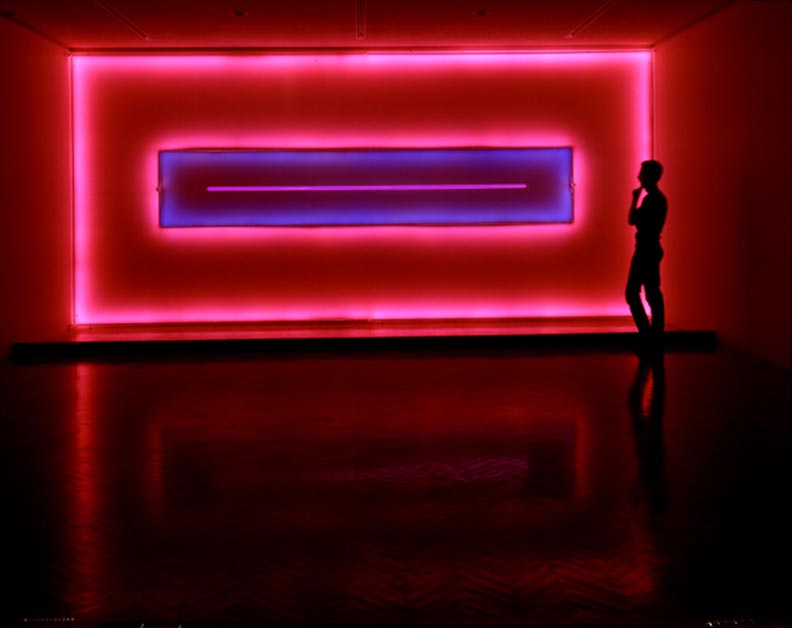

I’m currently working on a sound sculpture/performance piece, a passion of mine since 1966. For the past year, I’ve been dedicated to completing a sculpture I initially started back then.

Regarding the Fifty Foot Hose, I’m saddened to inform you that David Blossom, Kim Kimsey, and Larry Evans have all passed away. I believe Nancy is doing well; however, she relocated to the east coast after changing her name upon marriage, and I haven’t been able to locate her.

One of my two primary musical influences is Luigi Russolo, an Italian Futurist painter and musician. In 1913, he authored the manifesto of Futurist music, celebrating the emergence of the 20th century and the machine age. He revolutionized music with his invention of musical instruments called Intonorumori, or noise instruments, and his performances influenced many early avant-garde musicians. The sculpture I’m creating serves as an homage to his groundbreaking work.

How have you began crafting audio/visual pieces?

Cork Marcheschi: Back in 1966, during my time in graduate school, I focused on creating kinetic sculptures and sound sculptures. My approach has always been assembling pieces, drawing inspiration from random objects I encounter. One notable creation was a nightmare music box, blending electrical and mechanical components. Recently, I brought this old piece into my studio after 56 years and was thrilled to find it still functional. It was a poignant moment, reconnecting with my past self and recognizing the continuity in my decision-making process and logic.

Inspired by this, I began crafting smaller audio/visual pieces. Over time, I started organizing the sounds and developed a controller for playing them. I’ve since built 24 of these instruments. My influences include my experiences with Fifty Foot Hose, as well as my admiration for Edgar Varèse and Luigi Russolo, the Italian Futurist musician. Russolo’s Intonorumori instruments, described in his 1913 manifesto on futurist music, particularly resonate with me. He pioneered incorporating the sounds of the 20th century, such as electric motors and automobiles, into his compositions, marking him as the first true avant-garde musician. His mechanical and enigmatic instruments serve as the inspiration for my current work, which pays homage to Russolo.

Excitingly, I’m planning to collaborate on some musical recordings with Thollem McDonas and Nels Cline.

Could you share some details about the documentary being made about your work

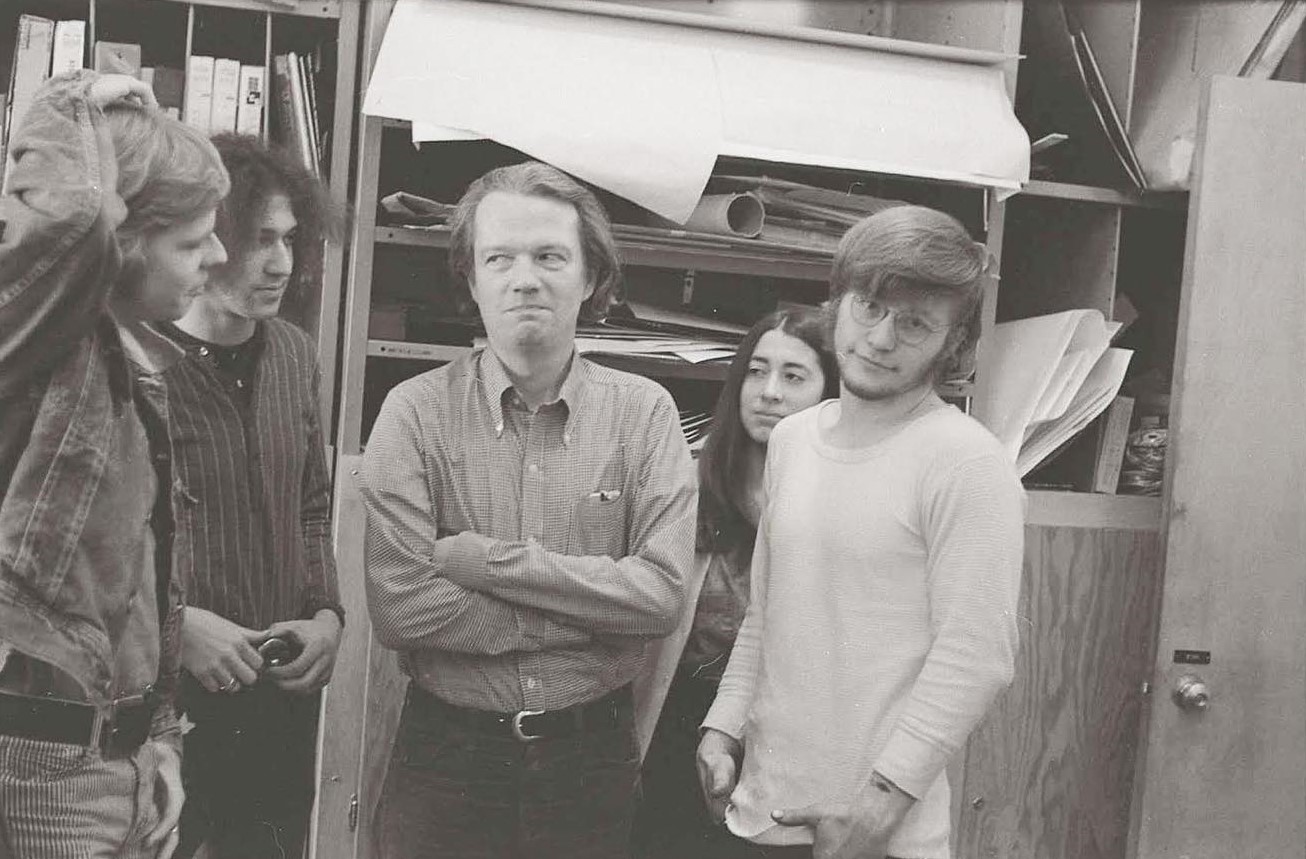

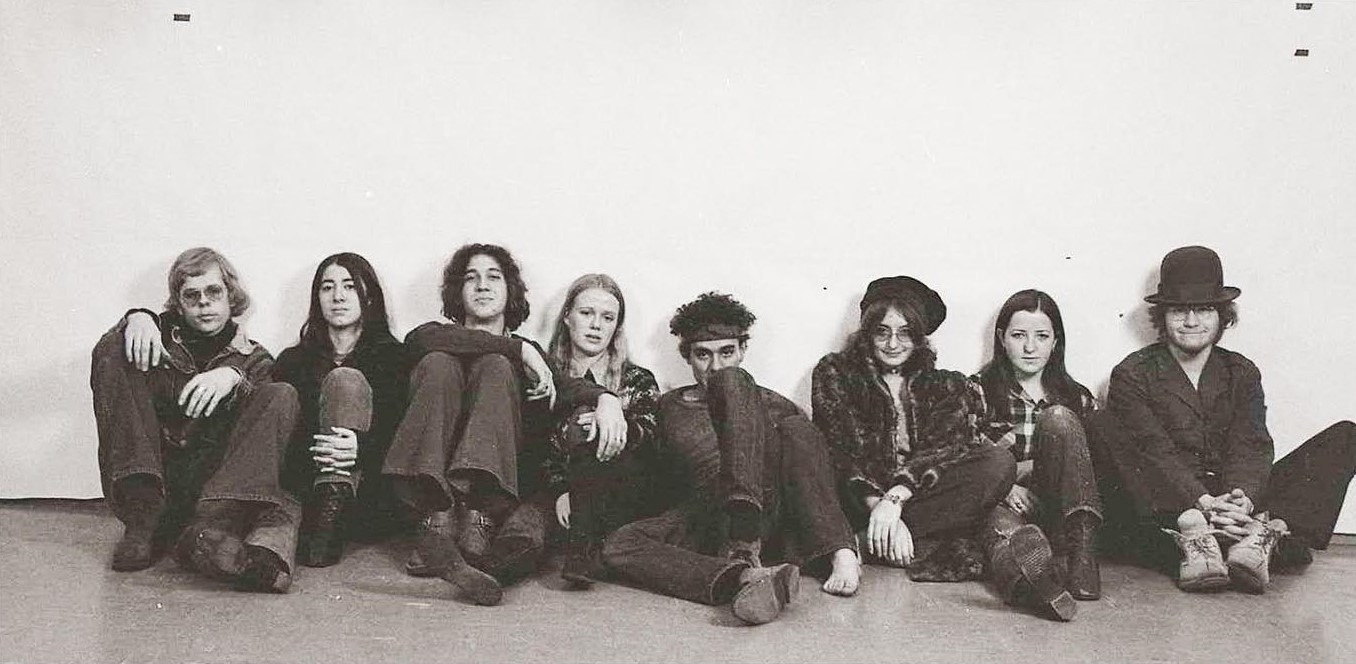

An eight-man film crew spent three days, working 12 hours each day, filming all of my new sculptural instruments and conducting a general interview with me at my home and studio. I anticipate that the resulting documentary, which will be around 15 to 20 minutes long, may be available in April. I’ll keep you updated on its release. Additionally, I’ve sent you a picture of the crew in my studio, as well as an image of my artwork featured on the cover of the book Lunacy: The 50th Anniversary of Dark Side of the Moon, which Pink Floyd is using as background art. The book also includes an interview with me.

Can you share some highlights from your experience receiving the DAAD Berlin award?

In 1978, I was honored to receive the DAAD, the Berlin award and residency. Throughout that year, my wife and I were guests of the Berlin government, residing in a wonderful apartment just off the Berlin Wall. It was a remarkable period during which I participated in five museum exhibitions, held a gallery show, and authored two catalogs. The experience was truly unforgettable.

However, the following years were marked by teaching and creating art until tragedy struck in 1982. One of my closest friends, Jim Morgan, who served as both my art dealer in Kansas City and a constant companion in my life, passed away at the age of 48 from a heart attack while riding his motorcycle. His untimely death left me devastated and profoundly depressed, leading me to halt my studio work entirely. Despite turning to sleeping pills and cognac to cope, I still struggled to find rest, averaging only three hours of sleep each night.

My other dear friend, Helga Retzer, whom I had met in Berlin in 1978 and instantly connected with, tragically died in a car accident in 1983. Losing both Jim and Helga, who shared a deep spiritual connection with me, left me adrift and without direction.

During this tumultuous time, I was awarded the National Endowment for the Arts grant in Sculpture, amounting to $25,000. I used this funding to take a hiatus from my artistic pursuits. However, I had one outstanding sculpture that needed installation, which led me to spend five days at the home of a Venture Capitalist involved in the early tech world. As I worked on the installation, we bonded over our shared passion for blues and jazz music. Intrigued by my enthusiasm for music history, he inquired about the possibility of producing a film on the contemporary state of the blues genre.

Seizing the opportunity, I proposed a budget of $250,000 for the film. He expressed interest and consulted his daughter, who had connections in the film industry. This conversation sparked the beginning of “Survivors,” which premiered at prestigious film festivals such as the Mill Valley Film Festival in California, the Berlin Film Festival, and the London Film Festival, before being distributed to theaters and released on video.

Following the success of “Survivors,” I embarked on another project titled “I am the Blues,” which allowed me to forge personal connections with many artists in the blues community.

Subsequently, I returned to creating artwork, focusing on large-scale pieces for both public and private buildings until six years ago. At that point, I felt the need to reconnect with my work on a more personal level and ceased exhibiting publicly. This decision has allowed me to delve deeper into my artistic expression and explore new avenues without the constraints of galleries or collectors.

You mentioned that you will be working with Thollem Mcdonas and Nels Cline on an upcoming project. How do you originally know them?

I’ve known Thollem for over 20 years. He introduced me to Nels, who was already familiar with Fifty Foot Hose.

What about Dada? I recently was in Cabaret Voltaire, a seminal club back then. Do you feel affiliated with Dada as well?

Dada has been and continues to be profoundly significant to me. In 1965, while attending the College of San Mateo, an English teacher introduced me to Kurt Schwitters’ W poem. He vividly described Schwitters standing on a table, holding a large drawn letter W over his head, and reciting the W 250 times, each time with a different tonal consideration. After completing the recitation, Schwitters tossed the drawn W on the ground, declaring it to be the greatest poem ever written. I instantly understood the essence of this act; it resonated with me deeply, and my entire being affirmed its brilliance.

The movements of Dada, Futurism, Suprematism, Constructivism, Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, and Fluxus are heroic chapters in art history that have continually inspired and motivated me. Before I began creating my own sculptures, I immersed myself in the rich and passionate histories of these movements from the early 20th century up to the mid-60s. During that time, I worked as a musician in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood at night, while devoting my days to school and researching art history. It was a truly wonderful period of my life.

My connection to modern history has always been deeply intertwined with my artistic journey and remains close to my heart.

Could you share your encounters and experiences working with Rick Cluchey and Samuel Beckett during your time in Berlin?

It was May of 1978 – I had received the DAAD Berlin prize, and I was living and working in Berlin for a year. It is one of the best awards an artist can receive. You are brought to Berlin, given an apartment, a studio, and a stipend. There is a network of people that help you get set up and make introductions for you. A dream situation.

A few months after arriving, I found myself in the back room of an empty Turkish storefront. It was cold, and there were 4 or 5 of us waiting for a rehearsal of “Krapp’s Last Tape.” This production was to be directed by Samuel Beckett. I was sitting on a wooden crate, eating double-fried French fries with curry ketchup. So how did I get here?

In 1965, my band was working six nights a week at Tipsy’s on Broadway. Broadway is in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood. Broadway was the last vestige of the Barbary Coast. From 1849 through the 1906 earthquake and through prohibition all the way into the early 1950s, Pacific Ave. The Barbary Coast had been the home of Shanghai-ing, Prostitution, dance halls, jazz, and every vice you might like. From 1939 to 1960, Pacific Ave. between Montgomery and Kearny was turned into the International Settlement. Bars, Dance Halls, Burlesque Houses, Restaurants, Jazz, and good times for anyone who was up for it. If you would like a little look at what the place was like, rent the film “Pal Joey” with Frank Sinatra. Many scenes were filmed on the street. The Settlement gave me my first inkling of – sex maybe? I was about ten and my family parked on Pacific. It was a Sunday afternoon, and we were walking up to Columbus Ave. to meet friends. We had parked in front of a Burlesque theater. I got out of the car and was presented with a life-size, black-and-white image of a dancer. She wore gloves, a flowered hat, high heels, and the welcoming smile and a sombrero that covered her from knee to neck. I looked at this image and thought, “there is something going on behind that hat?” I eventually learned that I was right. Working at Tipsy’s was great. Pee Wee was the mayor of North Beach. He had been on the strip longer than anyone else. Most nights, before the music started, the other club owners would gather at the Bar and talk trash, gossip, and get advice from Pee Wee on how to get club things done. Pee Wee knew how to massage goodwill. At the end of the night (2 AM), club owners and friends would show up for poker games. The waitresses would discreetly pour everybody’s drinks into coffee cups. Life was so simple and sweet. Tipsy’s was also home to the all-girl topless band. This was the idea of Vos Beretta (owner of the off Broadway). He helped mastermind “Robin and The Red Breasts.” These women were all cocktail waitresses that worked for Vos or Pee Wee. I thought it was a hair-brained idea but it was very successful. Especially when they learned to play the instruments.

One night at Tipsy’s, Pee Wee introduced us to a guy named Bud from the musician’s union. We were members of Local 6, as were all the musicians who worked on Broadway. That evening, we learned that every New Year’s Day, San Quentin prison hosted an all-day show featuring talent from the supper clubs, showrooms, nightclubs, and theaters in San Francisco. We were invited to play along with a lot of great people. We said yes on the spot. In a week, we got the details: show up at SQ by 7 AM. Then there was a whole list of things not to bring in, but we could bring two guests. Of the five guys in the band, no one wanted to drag anybody out of bed at daybreak. So I brought my mom and my girlfriend Trilby Noon. My mom wasn’t going to miss such an unusual opportunity. Aurora, my mom, was game for most anything!

We worked until 2 AM on New Year’s Eve and showed up at the prison five hours later. The prison guards went through our instrument cases, amplifiers, personal effects, and the ladies’ purses. Our IDs were checked. All of our IDs were fake. No one was 21 yet, but it was all okay. We were not left alone for a moment. The band was escorted to a backstage area, and the guests were held in a room just outside their seating area. We set up our gear behind the curtain and then hung out until showtime. The stage manager was a very interesting guy named Rick. He had a clipboard with times and acts. We had about 15 minutes before showtime. Rick and I talked. It was an easy and comfortable conversation. We talked about where he came from (Chicago), the glowing green relish in Chicago, music, and what the prison food was like. I didn’t ask, “What are you in for?” This guy could have been a friend. The ease and comfort of each other were palpable. Then it was time for the band to go on. We shook hands, and I didn’t say, “See you later.”

These New Year’s shows were filled with top-line talent: Eartha Kitt, Vince Guaraldi with Bola Sete, Buck Owens and the Buckaroos, Paul Desmond, and six hours of singers, dancers, comedians, and the most appreciative of audiences. It was our time to go on, and I said goodbye to Rick. I was very aware of not saying, “See you later,” “Let’s hang out,” or “What’s next for you.” We shook hands and looked at each other. When we finished our set, we could join our guests and see some of the show. About an hour in, Eartha Kitt came on. She was relaxed, very casually dressed in black Capri pants, a sweater, and flats. The audience really roared. She approached the front of the stage and spoke directly to the sea of captive men. What a natural entertainer. The ease of her performance made it all the more personal. She took no cheap shots and treated the crowd with awareness. After Eartha’s spot, we were escorted to the cafeteria.

A massive stone and tile room greeted us. The center of the room featured a long table adorned with carved ice swans holding caviar. The prison had a culinary school for the inmates, and they were really putting on a show. It was impressive. My mom got in line next to Eartha Kitt. What a treat for me to watch my mom and Eartha talking and laughing like old friends. They sat together at an empty table, swapping stories and enjoying each other’s company. My mom was genuine people. Trilby and I sat with Vince Guaraldi and Bola Sete. Vince’s huge hit, “Cast Your Fate to the Wind,” was still holding on to the charts. I had worked with Maxi Weiss, the founder of Fantasy Records. There were some great laughs about the Treat St. studios and the casual way things came together there. Dave Brubeck, Lenny Bruce, Cal Tjader, Creedence Clearwater – they all came out of Treat St. in the South Mission. Nothing was precious then; it was all about the music. We hung out for another hour and slowly exited with all the protocol we had entered with.

In 1970, my working musician’s life came to an end. I obtained an MFA degree and a contract to teach at the Minneapolis College of Art and Design.

Was it good fortune, naive bumbling, or just not knowing how not to do anything properly that landed me in the reopening of the Walker Art Center in ’71? I got a NYC gallery in ’73 and a Toronto gallery that introduced me to the Cologne and Düsseldorf art fairs. From that, I got a great German dealer and started a wonderful run of showing around Europe. Then, in 1977, I was awarded the DAAD Berlin Prize. This is the premier artist award! You and your family are brought to Berlin for one year. You have a nice apartment, a museum show, any introduction you can imagine will be arranged, and you get to work in a community of professional painters, sculptors, musicians, dramatists, and poets.

Donna and I arrived in Berlin on January 10th, 1978. A young man was waiting at the airport holding a sign with “MARCHESCHI” written on it, making it easy to spot. It was cold and grey, and I was feeling groggy. We were taken to Wannsee, an area of Berlin that is at least 40 minutes from the city center. This part of the city had been spared by the Allied forces. They recognized it as a great vacation area and left it untouched, with large homes and gardens lining a lake.

We were dropped off at the Literarisches Colloquium. In the summer, this was a destination for writers, hosting symposiums, retreats, and more. But in winter, it was a huge space filled with empty rooms, just the two of us. There was no food, coffee, or tea available there. However, there was a bar across the street that served some food and coffee.

This was our introduction to Berlin. I had a Japanese expat artist friend named Shinkichi Tajiri. He lived in Holland but taught at the HDK art school in Berlin. On our second day, Shinkichi picked us up and drove us to our apartment. We moved into a spacious place on #1 Mariannen Platz. From my studio window, I had an up-close view right across the wall. The neatly clipped grass between the two walls was a bit of a puzzle. The simple layout of the wall was: the West wall, tank traps, guard towers, and then a clean break for a nightmare putting green and the barbed wire, tank traps, and the East wall. There were some anti-personnel landmines. A few times over the course of my year, I heard a couple of little explosions. Apparently, a multitude of rabbits lived and ran free between the walls. Occasionally, rabbits would trip one. “GOOD MORNING EAST BERLIN!!!” We were welcomed by the Director of the DAAD, introduced to our contact person, and then introduced to our banker. We had never had a banker before, but we did now.

About six weeks later, there was a welcome party for all of the DAAD recipients. It was a very nice affair, with good food, good wine, lots of talking, and a warm ambiance. A dark-haired, slightly rumpled (in the artiste way) gentleman approached me. He asked if we had met before, and I said I didn’t think so. I asked where he was from, and he said Chicago. I told him I was from the SF Bay Area. He mentioned that he spent a lot of time in the Bay Area. I asked where, and his answer was San Quentin. It took about 10 seconds for the two of us to put it together. He was the stage manager in the big house, and I was the music. I got one of the best, most honest embraces that I ever had. Time collapsed, and we were the friends we could have been.

Rick Cluchey was there along with a company of actors. Rick had been sent to San Quentin in 1954, given a life sentence for a two-block carjacking and an armed robbery that went bad. In 1957, a traveling theater company brought “Waiting for Godot” to the prison. The play, especially the character “Lucky,” was absorbed by Rick. He got it! People in prison understood Beckett with no effort. Rick started the Drama workshop and wrote many plays, including “The Cage.” Eleven years into his sentence, Governor Pat Brown commuted Rick’s sentence for good behavior and for establishing the workshop. In 1966, Rick was released and found a new life filled with opportunities. One of those was to work as an assistant director for Samuel Beckett in Berlin. While he was there working with Beckett, he also premiered “Krapp’s Last Tape.” Beckett thought Rick’s version was the all-time best.

So, Rick and I got together. We talked about music, art, theater, Berlin, and what each of us was going to be doing. Rick was going to be directed by Sam in a production, and the company was taking one of Rick’s plays on the road. I was going to be doing five museum shows. He wanted to see my work, and I showed him images from the catalog that was going to accompany my shows. Rick looked at the images and got excited. “You do light stuff,” he said. I answered yes. Then he said, “Come work with us and Sam. Design some cool stuff for us.” And I did. It is amazing what can happen when you walk in with no expectations. My pattern of only having a handful of the puzzle pieces has served me well. My level of sophistication was very close to Judy Garland and Mickey Rooney putting on a show in their parents’ garage. If I had known the baggage, politics, drama, and petty realities of the world I occupied, I would have never had time for the art or music.

The first time I met Sam (that’s what we called him) was at a chili party at Rick’s apartment. There were about 20 people there, eating chili, sitting in the kitchen and the living room. Louis, Rick’s youngest kid (he was about 5 at the time), was Sam’s godson. Seeing Louis jump onto Sam like a big toy, the sound of Tom Waits in the background, and Rick coming over to me saying, “Man, we’re out of chili,” all made Sam an artist you could hang out with.

Sam wasn’t a hero of mine. I knew his work, and his work was constantly being referenced and still is. I listened to conversations floating around Sam’s chair. Some people tried to sound smart, using words with 14 syllables. Sam was polite and patient. Academic questions can suck the life out of most any situation. When most of the guests left and it was only the theater company hanging around, I asked Sam what he thought about his work being performed in prisons. Sam told me that the inmates understand the work because they live in it. He never charged any royalties for his shows in prisons. Instead, he requested letters and notes from inmates who had performed the work.

For me, the Beckett experience was like being in the presence of a bird of prey, an energy focused and an eye that sees the absurdities that pass for life. He was a very intense, nice guy, easy to talk to, and private. We had some good conversations about the use of light in some of his works, his time with Joan Mitchell (she loved to argue), the French Resistance, and more. He instantly understood my remarks about the cone of light versus the focal landing of the light. I brought it up because I liked his one-acts “Not I” and “PLAY.” Light played a very important part in both of these. I can’t believe I was offering Beckett suggestions on considering options for lighting. It was friendly and easy. Thinking about this 40-plus years later, I blush.

Sam directed three of his works at the Schiller Theaters. He worked with Rick and the SQ Drama Workshop actors. Other than the Schiller Theater, which was upscale, everything else seemed to be more like studio work. The strange rehearsal space behind the Turkish Imbiss, the Kunstler Haus Bethanian, and wherever things were going to be happening or wherever a space could be had for free. I am so grateful and lucky to have bumped into a once-in-a-lifetime situation that was heady and so much fun. No pretension or artifice. The art came first, everything else after. I am still friends with two members of the San Quentin Drama Workshop, John and Carroll.

That year cast a spell on all of us who worked together. The fairy dust never seems to shake itself out of our lives, certainly not mine. The last gathering where I saw Sam, I told him about my introduction to his work.

In 1963, during my senior year at Burlingame High School, the school, though public, was very well funded and had a full representation of the arts. The drama department staged Beckett’s “Happy Days,” with Anthea Lee as the featured performer. I had known Anthea since kindergarten in 1951, and by 1963, she had become a dedicated actor. What a wonderful introduction to Beckett for me.

I told Sam about the theater department at Burlingame High School and how in 1963, my childhood friend Anthea Lee provided my first experience with his work. The performance was very effective and well done. Seeing Anthea slowly disappearing into the sandbag opened my mind to performance art.

Sam paused, and then gave me a very amused smile, one that gave the Mona Lisa a run for her money. Over that year, conversations had circled around prisoner audiences and their acceptance and familiarity with work that many members of the general public found opaque. But no conversation approached a high school presentation in a California bedroom community. Anthea Lee will never know that her performance of “Happy Days” was discussed with Beckett. Thanks, Anthea, wherever you are.

“Pushing the boundaries of avant-garde music”

How did the meeting with Brian Rohan unfold, and what was his initial reaction to the band’s unconventional sound?

The following recounts a significant event that remains largely undocumented, involving the signing of the Fifty Foot Hose.

I first encountered David Blossom at a casual gig toward the end of 1966. We were set to accompany a singer at Bimbo’s 365 Club. As we awaited the vocalist, we found ourselves discussing our dissatisfaction with the current music scene.

David hailed from the folk and folk-rock tradition, possessing remarkable skill on the guitar and an extensive knowledge of music. Meanwhile, I approached music from an R&B perspective, infused with avant-garde 20th-century art and musical influences. By the end of the evening, fueled by our shared passion for music and art, we resolved to meet the next day and establish an electronic/rock band. Despite our burgeoning families and other commitments, our enthusiasm was unwavering.

We assembled a band and practiced diligently. One memorable session took place at a friend’s house in the Haight, where we played amid a backdrop of tightly packed hippies. The acoustics of the space, coupled with our fervor, resulted in a remarkable demo recording.

However, the challenge lay in finding someone willing to listen to our unconventional sound. The Fifty Foot Hose was certainly a tough sell, pushing the boundaries of avant-garde music. Yet, fueled by a fervent belief in our art and a desire to change the world—or at least sell a record or two—we pressed on.

One name repeatedly surfaced as a potential advocate: Brian Rohan. I reached out, and after some persistence, secured a meeting at his office on Franklin Street. Upon entering, I was transported into a world of rock ‘n’ roll memorabilia, reminiscent of a successful lawyer’s office with a teenage twist. Amidst Fillmore posters, rock albums, and eclectic artwork, Brian exuded a sense of camaraderie and passion for music.

Brian, a lawyer who represented activists, musicians, and the underdog, shared our vision of blending art, music, electronics, rock ‘n’ roll, and Dadaism. Despite his initial inquiry about our drug use (which we denied), he listened intently to our demo, recognizing its uniqueness.

Three weeks later, Brian arranged for a Mercury Records representative, Robin McBride, to hear us play. After an impromptu audition at my mom’s house, we were signed on the spot, with Brian expertly handling all contractual matters.

Several weeks later, Brian invited me to an event at his home, a gathering of musicians and industry figures that showcased the vibrant music scene of San Francisco. Despite our humble beginnings, the Fifty Foot Hose found itself amidst luminaries like Santana, the Grateful Dead, and the Steve Miller Band—a testament to Brian’s belief in our potential.

The highlight of the event was a presentation by representatives from BMI and ASCAP, who sought to sign the bands and their songwriters. What started as a dry presentation quickly descended into laughter, with Rock Scully’s blunt question—”WHAT ARE YA GOING TO PAY US?”—breaking the tension and leading to a fair agreement.

Looking back, this moment in San Francisco’s music history holds immense significance. Brian Rohan’s unwavering support and advocacy provided a lifeline for artists navigating an ever-changing industry landscape. His commitment to musicians and his role as a bridge between the establishment and the counterculture were instrumental in shaping the creative landscape of San Francisco.

As the years passed, the Fifty Foot Hose’s album found renewed appreciation, thanks in part to Brian’s initial support. Its enduring presence serves as a testament to his belief in our art and his enduring legacy as a champion of artists.

Thank you, Brian, for believing in us when few others did.

Could you elaborate on your encounter with Brian Rohan and how it led to an audition with Mercury Records?

David and I comprised the band. David was an inspired musician who could play like breathing. He had grown tired of folk, folk-rock, and the current music scene. Meanwhile, I had been kicked out of playing in Las Vegas with my R&B band, leaving me so depressed that I did nothing for six months.

Then, I received a call from the musicians’ union to play a casual gig in San Francisco. That’s where I first met David. We instantly liked each other and both wanted to pursue something new. I aimed to incorporate what my fine art background had exposed me to, like Luigi Russolo, Edgar Varese, John Cage, and Stockhausen. David, on the other hand, was eager to explore something entirely fresh.

As I previously mentioned, I met Brian Rohan, who arranged an audition with Mercury Records for us. Over three weeks, we managed to assemble a band. David wrote some excellent songs with an experimental core, while I crafted my own electronic instrument, and we began rehearsing.

To support ourselves financially, we returned to the clubs I had been playing in since 1962, performing regular club music. Late at night, we would test out our new material. Robin McBride was the individual who signed us. Once we entered the studio, he gave us free rein to do whatever we wanted.

We recorded basic tracks at Sierra Sound in Berkeley and then refined the record at Trident Studios, located in the basement of the Columbus Tower in North Beach. The sessions were incredibly open, with Dan Healey, our producer, offering unwavering support for David and me.

The songs were crafted in the studio, long before the advent of digital tools. It was a wonderful time, although we never had a permanent bass player. Larry Evans filled in, but he couldn’t fully grasp the band’s vision.

Unfortunately, as I may have mentioned, David, Kimsey, and Larry have all passed away.

Did you do a lot of gigs back then?

We worked in clubs, at Be-Ins, and at concerts.

What are some of the most memorable shows and what would be the craziest?

We did a show with a band called the 25th Century Ensemble, a large commune band living in the Santa Cruz Mountains. They had an instrument called the space bass, entirely made of metal with numerous strings, allowing multiple people to play it simultaneously.

The venue was in Redwood City, though I can’t recall the name of it. It was an auditorium, and the night was perfect—it was New Year’s Eve, either in 1967 or 1968. The crowd was eager for a good time and open to all the music we played. We established a connection with 500 or 600 people that night. It was an incredible human experience to feel connected to others, to share your dreams with them, and to have them understand and appreciate it. What a feeling! It was the best and craziest feeling combined.

You played with Silver Apples? Were you also familiar with The United State of America or Doug McKechnie…

We never played with the United States of America, but we did have the opportunity to work with the Mills College Tape Music Center. Don Buchla had his first synth there, and Terry Riley was recording ‘In C.’ It was a magical place.

Can you reflect on the 1994 reunion of Fifty Foot Hose?

I was asked to play a benefit show for Aquarius Music, a very good record store that supported the avant-garde. So, I asked some friends who knew me well and my music to join me. We got together in my studio and played for a couple of weeks. Jello Biafra was a fan of the Fifty Foot Hose and showed up for the show. Everything that we have done since that show is totally in the spirit of the original hose.

Tell us about some of the most important Exhibitions you had…

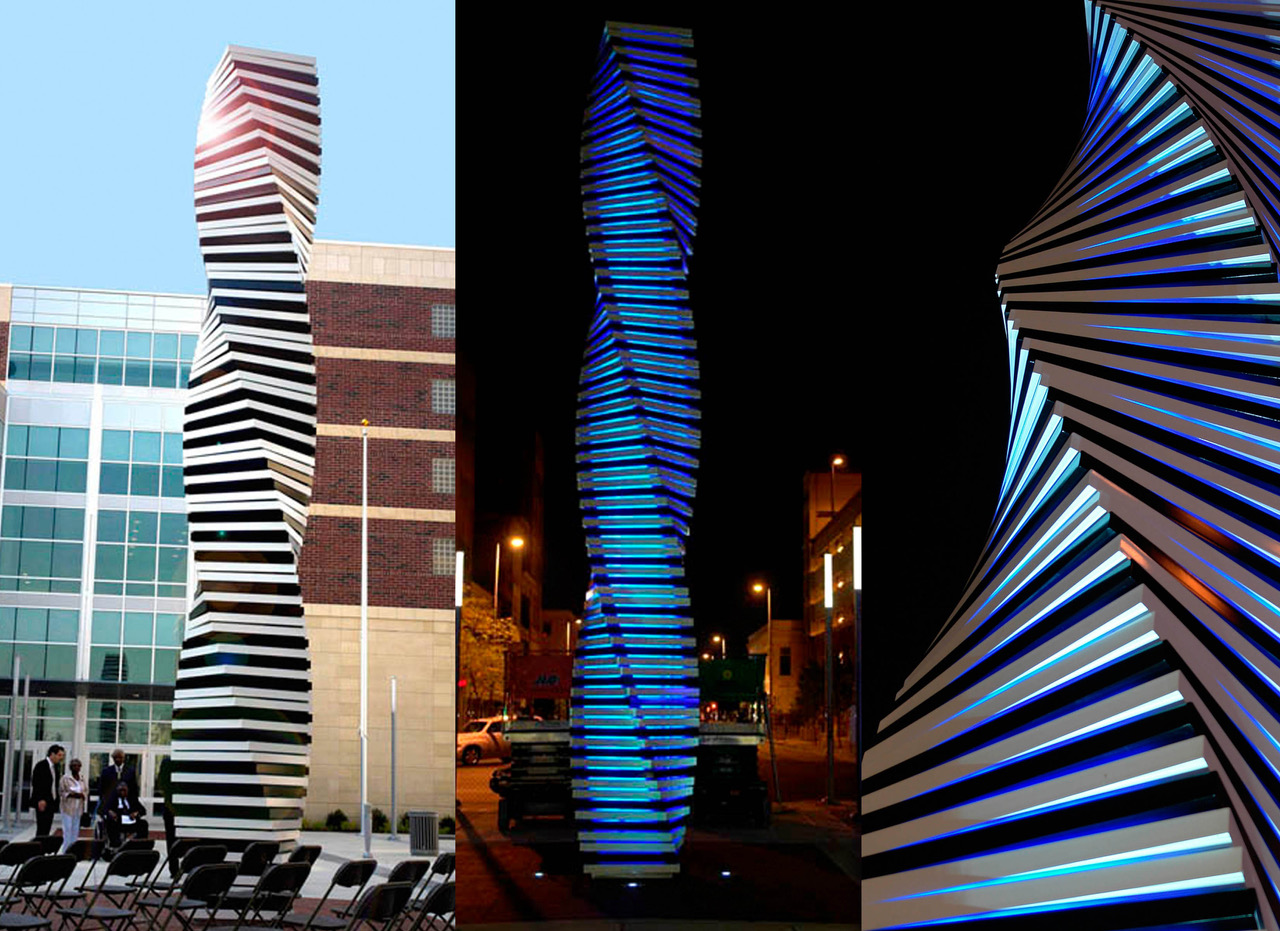

The art shows that stand out most in my memory include the opening of the Walker Art Center in 1971, the Berlin National Gallery in 1978, Gallery M in Germany from 1973 to 1989, the Folkwang Museum in Essen in 1974, the Minneapolis Art Institute in 1983, the Morgan Gallery in Kansas City with several shows from 1973 to 1983, the Meisel Gallery in NYC in 1980, the Museum of Neon Art in Los Angeles in 2007, the Art Tatum Column in Toledo, Ohio in 2013, Victoria Peak in Hong Kong in 1990, Canal City in Fukuoka, Japan in 2009, the Braunstien Gallery in San Francisco from 1989 to 2018, and many private sales to collectors.

Where does your love for Blues music originated from?

When I was 7 or 8 years old, one Sunday, I walked with my grandmother to buy eggs from a chicken coop about 8 blocks from our house. It was located next to a Pentecostal Black church. The windows were open, and an enormous, miraculous sound emanated from those windows. I froze—my scalp tingled, and my entire little boy body felt something big and amazing. I was lit up! I asked my grandmother what it was, and she said it was music. I had her bring me back several times. Eventually, we went in and were welcomed. I can still feel it. Black American music from the 1930s to the 1980s fed my heart and soul. I had the opportunity to work with Willie Dixon, Baby Do Castro, John Lee Hooker, Percy Mayfield, and many others.

And so many more. One of my best interviews was with John Hammond Senior. WOW. I still listen to blues and R&B all the time.

What was the process for the release of Survivors in 1982, a documentary on well known blues artists that continue to carry on the blues tradition. What about I am the Blues?

I wanted Willie Dixon to be part of Survivors, but he was undergoing leg surgery due to diabetes. So, I set some money aside from the Survivors budget. Six months later, Willie was ready. But the interesting part of the story is there was a steakhouse in Minneapolis where I heard they had a wonderful blues and boogie-woogie player. When I went in to see him, I recognized him from old pictures of the Big Three Trio: Willie Dixon, Baby Doo Carton, and Cool Breeze. Baby Doo was sitting at the piano playing great stuff. When he went on break, I spoke with him and sat through two more sets. I asked if he would like to try to get together with Willie again and if we could tape the reunion. He said he would call Bill (Willie) and see. I got a call back in a week with Willie’s Home Number. I called, and we set up a date to film/record “I Am The Blues” in Denver, Colorado. We were at the Performing Arts Center. We had enough time and money for one hour of rehearsal and one hour to shoot the one-hour show. It was amazing – it all worked out wonderfully. BET (Black Entertainment Network) and BBC Two bought the show.

And I can’t separate my art life from my life. I have had an amazing life, working with amazing people around the world, showing and selling my art to great collectors and museums. My mother was an opera singer who was very supportive of my love of art and music. She and my father came to see us play in the North Beach strip clubs, the Fillmore, the Be-Ins, Las Vegas – all of my bands always rehearsed at my house. I am a very lucky guy to be born an Italian immigrant and to be raised in an immigrant neighborhood. I got to see all the great blues players – Lightning Hopkins, Muddy Waters, Ray Charles in 1961, James Brown, Bobby Blue Bland, etc. And then Jimi Hendrix, The Airplane – we played with Big Brother in the College of San Mateo cafeteria. The list is too long to even think about.

Klemen Breznikar

Cork Marcheschi Official Website

Fifty Foot Hose | Interview | Cork Marcheschi