Tim Hodgkinson | Interview | “I want to be in the world that’s going by”

Tim Hodgkinson, born in 1949, is a distinguished English musician whose work spans performance, composition, and improvisation. As a co-founder of the avant-garde rock band Henry Cow in 1968, he significantly influenced the progressive music scene.

His versatility in playing multiple instruments and his collaborations with various artists highlight his broad impact on both contemporary classical and free improvisation music genres. Hodgkinson’s contributions extend to academia, where he engages in teaching and lecturing on music theory and practice.

In the following interview conducted in October 2023, Tim Hodgkinson reflects on his upbringing, characterized by isolation and introspection, which fostered a deep affinity with animals and later sparked his interest in Marxism and music. Influenced by the works of influential figures such as John Coltrane and Messiaen, Hodgkinson’s musical trajectory was shaped. His exploration of diverse musical traditions, ranging from Central Asian music to spectralism, informs his compositions and collaborations. Hodgkinson maintains a balance between creative pursuits and introspective contemplation, engaging in ongoing projects and performances while reflecting on memory and identity. His eclectic taste in music, spanning from avant-garde to classical, underscores his enduring commitment to artistic innovation.

“Our generation of friends were feeling as if every day was a new discovery”

Tim Hodgkinson: If you want the dope on my ancestry, you can find it in Ben Piekut’s book. Let’s say I grew up in a loving family, but I was quite isolated in childhood because my sister and brother were both a lot older and were into different scenes already, plus we tended to live out in the country, not in any village or town. I remember having a strange feeling about the furniture in the house, the ashtrays and candlesticks and stuff: it just didn’t seem right, I mean in the formal quarters that my parents frequented. I think it was a feeling that there was some kind of separation from reality. This was before I had any experience of class differences; maybe I was a kind of innate socialist. Anyway, I became quite an introverted child capable of occupying myself for days by building strange contraptions. I also liked tree houses and making tunnels under bushy corners of the garden and beyond. My fantasy life at this time was mainly concerned with animals. I was deeply impressed by such books as Tarka the Otter, written by Henry Williamson, who I discovered years later had been a fascist, brown-shirt style. In fact, the whole story of Tarka is a kind of terrible inevitable procession towards the last scene in which he is hunted to death. I am still to this day trying to figure out what connection (if any) my animal obsessions then have with my adult interest in animals that began when I realized that Marxism had failed to recognize the complexity of matter in general and of organic life in particular. These days I am mindful of birds and animals whenever I see and hear them.

In any case, my home life—in many ways ideal—had a kind of stultifying habituality to it that one day was shattered by the experience of hearing the LP of Coltrane’s ‘Africa Brass.’ At this moment, I realised that there was another world that was more real because more intense, and I wanted that world very badly although I could hardly connect this feeling to any practical project of becoming a musician. By now I was at boarding school, which was a welcome opportunity to at last meet my peer group. We had compulsory chapel every morning, and one day I shuffled in with my usual cynical and dejectedly atheistic shrug, to be met by sounds that seemed to be coming from outer space: it was Messiaen being played on the school chapel organ. This was another crack in the wall. Both of these moments were eruptive openings in the bounds of normality. At around the same time, I had my first mystical experience. I had taken up long-distance running as a way of avoiding team sports, which I hated because I was always worried about letting down my own team, and one afternoon I ran up a long rising valley and as I came out on the top, the universe flooded into me and me into it. This was before I got my hands on any drugs.

At this time at school, we were digging the Beat poets, hearing Charlie Mingus, climbing out of the buildings at night to go and read poetry and drink vodka in a disused railway hut. I was ordering every new Coltrane release on Impulse Records by mail from a shop in London. When a new one arrived, we drew the curtains and lay on the floor to listen to it. Our generation of friends were feeling as if every day was a new discovery that barged in on us and changed everything. It was like a huge cornucopia of experience flooding in. I also had a band briefly at this point. I think we played one gig in the school music room. It was some kind of free jazz; our pianist didn’t like to stop between the numbers, he just kept going, and we showered the audience with torn-up paper.

Then I left school and went to India to search for the truth. This involved smoking a great deal of hashish. I didn’t find it. Coming back to the brutal cold light of England was hard, and I immediately started at Cambridge University where once again I felt very isolated, at least for the first few weeks. Then I started to notice a couple of other fellows had long hair. And one night, some young ladies came round, ostensibly on a fund-raising mission, and things started to loosen up. Me and my future wife joined an experimental theatre group where we both acted as lunatics in a production of Marat/Sade. I must have started playing the saxophone again—I’d hardly touched an instrument in India—and when I ran into this guitarist called Fred Frith, he thought I was quite a serious musician because I’d forgotten to take my sax strap off. Luckily for me, for some unknown reason, he invited me to join a group he was thinking of putting together. But the first thing we did was to play music for a radical dance piece based on the idea of the atomic bomb at Hiroshima, and this was pure free improvisation on sax and violin: neither of us had ever done anything quite like that, and it was triggered by this situation of improvising around an idea or feeling.

Did I know I wanted to become a musician at that point? I’m not so sure. I knew music was very important for me; I had no idea yet of the kind of concentrated hard work that being a musician—well, in fact being anything—might require. I was typical of the students of that time, enjoying the lazy self-indulgent opportunity of a few years of being paid for (university was free in those days), reading a few books, and not having to earn a living. It was only some time after Henry Cow had got started, when we had played a particularly bad gig, traveling home in the van with a friend of the band who told us in detail about how awful we had been, that we realised together that if we were going to do this thing, we were going to have to do it like we really meant it. But for a couple of years, I still felt undecided. I was into the music and I was into social anthropology. One thing that finally tilted me towards doing the music was, when I got my degree, my tutor said that I should take an academic job because a university was a good place from which to watch the world go by, and I thought, no, I want to be in the world that’s going by. As a result, I quickly discovered that I was in this music group that was eating my life, and I had very little time for anything else. Perhaps I did think that I was now a musician. But at the same time, there were a lot of things that, at least in principle, I didn’t like about the professional attitude of musicians. I didn’t like the emphasis on proficiency and equipment as against ideas and intentions, and I didn’t like belonging to a social field that imposed its own particular rules, sanctions, and rewards. (Hoorah for Pierre Bourdieu!) So let’s say I was a Henry Cow more than a musician as such. The worst kind of musicians as far as I could see were the orchestral players, who had their salaries and worked strictly to rule and read their parts effortlessly, never thought about music, and hated to play anything out of the ordinary. But even the jazz players seemed to share a defensive kind of sense of humour that pissed me off.

“I was using ritual structures inside my compositions as a kind of implicit layer that would give the music a secret organizing principle”

And there was another thing, which was that I was very interested in composing, and I kind of discovered I could do something in that direction, and it seemed almost like it was the opposite direction to being a good musician, and that created all kinds of trouble. That was the first split, that was when I first felt a tension in my creative life that took me, well, decades to resolve, no, not resolve, but to accept and to find a way to work with, in fact. So, as I feel about it today, I’m a person who has a profound respect, and even a kind of envy, for someone who can put their entire being down the cylinder of a clarinet or into the gesture of hitting a drum, but I am not that person. Of course, it’s also true that these people are just great performers who create the illusion that that’s what they are doing. And it’s also true that I’ve probably gotten better at doing that myself, and I’m thinking here that, in a round-about way, social anthropology led me back towards music from a different angle. From the start, social anthropology underwrote the idea that music is (secretly and potentially) more of a total art than it seems. In most cultures, the arts are not so divided and specialized as in “Western” culture. So I was using ritual structures inside my compositions as a kind of implicit layer that would give the music a secret organizing principle. Obviously, I had to think about how this sat with a progressive view of history, and no doubt I never resolved the problem, but this is something that I’ve never altogether stopped doing. On the other hand, social anthropology itself was undergoing huge changes. There was the new idea that what might be meaningful in a culture might be something to do with what its members say to each other, rather than a set of answers to an authorial question that the ethnographer had carefully brought with them from the world of academia. So written ethnography becomes potentially polyphonic, a record of actual social life. Instead of the attempted administration of a marginal zone, it becomes a field of energy with implications for our understanding of democracy as well as for artistic practice. In my music, its presence grew from a structural use of ritual forms to an artistic deployment of multiple worlds, and, within them, multiple voices.

But there was another soc anth connection to be discovered, which happened much later when I started going to Siberia from 1990 onwards. And this was first to do with performance and then also with composition. Ken Hyder and I had been meeting up and playing together regularly; we were neighbours in London and shared an interest in both socialism and improvisation. One night we were talking about how some players seemed to play great every time and was there some trick to it, and I remembered the shamans from my soc anth days. So we both read books on shamanism and wondered if a shaman’s preparation to enter an altered state could work for a musician looking to get into the maximum improvisational state of mind—if such a state of mind existed. A little later, I ran into Boris Podkosov at a festival in Moscow where I was playing (temporarily) with the Kalahari Surfers, and he invited me to his festival in Khabarovsk, a Siberian city which is, relatively speaking, not far from Japan. So I said right, let’s do it with Ken, and Ken said right, let’s talk to the British Council, and soon we were setting off for a tour of Siberia under the logo “In Search of the Soviet Shamans.”

Of course, at that time, we imagined that this was something that could only happen once in a person’s lifetime. But in fact, we would return many times. What was fascinating about Siberia? Well, you can call me a soggy romantic, but there were moments and places in Siberia that really struck me deep. I mean that they seemed to become immediately central to my existence—places that I had never seen before (the view southwards towards Samagaltai from the top of the pass on the road down from Kyzyl in Tuva) which nevertheless seemed to be places that I had always known and were in some unfathomable way my planetary home. And then there were other moments, such as when the shaman Yeremi pulled a red-hot knife across his tongue right in front of us with a great hiss of escaping steam and ran his fingers up and down our bodies to clean out any badness: years of therapy delivered in ten dramatic seconds!

Working with Tuvan musicians such as Gendos Chamzyryn, and others in southern Siberia, listening and thinking about, and trying to understand, this whole tradition of Central Asian music that begins from the idea of the unity and continuity of sound rather than the relations between separated notes, prepared me for my encounter with spectralism as a compositional approach. Back in London, I’d borrowed a pile of CDs from Chris Cutler, thinking that I should make more of an effort to get to grips with contemporary electro-acoustic music: it all sounded overly smooth and polished to me, lacking in energy, emotion, or a close relation to life, but one CD at the bottom of the pile stuck out like a sore thumb, and, in particular, a violent and distorted piece called ‘Pierres Sacrées’ by Iancu Dumitrescu. Through Ed Baxter and the London Musicians’ Collective, we were able to invite him to London with his musicians. They drove from Bucharest in two cars to play one concert at the Purcell Room. I interviewed Iancu and his wife Annamaria Avram the next day and a big friendship began that led both to me playing bass clarinet in their ensemble and to their ensemble performing some of my own pieces. In the longer term, I think the most useful thing from meeting Iancu wasn’t spectralism as such, but the application of phenomenology to music. As a composer, from the very beginning I was always concerned with the ideas underlying Western art music. But also from the beginning, unlike most schooled contemporary composers, I fully grasped and adhered to the fact of recording—unsurprising because my most formative musical experiences were in a rock band. This, for me, already brings music into far closer contact with the immediacy of the world, by which I mean the quality of our experience of the world around us in all its informal, contradictory, and surprising aspects. Phenomenology in terms of music is the awareness of the exact way in which sounds appear: do they arrive suddenly or do they emerge from behind other sounds? How do they die away, or do they disappear behind something else? So this is like applying to music the way that we listen to sounds in the non-musical world. And when we go for a walk in the woods, we hear the songs of the birds of different kinds and the sound of the wind in the trees and perhaps a distant motorway and a cow mooing in the background, and none of this is synchronized but it sounds natural and perfect. So this began to be the way that I put my music together, perhaps first in K-Space which was the trio that Ken and Gendos and I formed around 1996, but also and increasingly in my compositions. One of the more radical K-Space projects was a CD called ‘Infinity’ that uses software to recompose itself each time it is played. In this way, we hoped to reflect both on this new musical approach and on the journeys of the Siberian shamans whose rituals can never guarantee that the spirits will behave in a predictable way.

I’m not going into factual details about Henry Cow or the Work, as all this information is already out there for anyone who cares to find it. Furthermore, I’ve forgotten most of it, and it seems to belong to a different world in which I no longer recognize myself. I think my memory works in phases. For example, when we were first assembling the Henry Cow boxed set, I started listening to the material and I thought, “Ah, some of this stands the test of time.” And around the same period, we were doing intensive interviews with Ben Piekut for his book on the Cow. So that was a period when Henry Cow was—after a gap of decades—again taking up some of my mental space. Another example was a few months ago when I got an email from a school friend I hadn’t spoken to in over fifty years, which led to me going through a box of old letters and recalling some of the events and atmospheres of that time in my life. I had apparently led some friends in chanting Indian mantras on a beach in Devon in the winter of 1967, but of this itself I had (and still have) absolutely no memory.

Generally, I’m most concerned with what I’m doing in the present. One of the things I’m doing is attempting to write a second book, which is intended to be non-academic, although I doubt that I’m capable of writing something that’s an easy read. I don’t yet know if this is going to work; I have to go a bit further with it to find out. My soc anth interests are still alive and kicking, and I recently contributed a book review of Nastassja Martin’s (very impressive) writings to the Shaman Journal in Budapest. Then I’ve been revising a long composition (40 minutes) that I wrote in the Covid period. My intentions are, as usual these days, to elicit different kinds of listening either simultaneously or successively. The piece starts as an elegant and intricate piece of contemporary music full of motifs and intervals, and degenerates into something more spectral and intense. At the midpoint, there should be some kind of special event, possibly a short, very short, film, and then the second half begins quietly and ritually, and the music takes us through three different quite extreme sound-worlds, realized with computer-prepared sounds, and identified as the Rain, the Desert, and the Volcano. Apart from this, I am also mixing some studio sessions of my improvising trio Torba with Gandolfo Pagano and Fabrizio Spera, recorded in Sicily. Then I have to learn a clarinet part for a piece by Thanos Chrysakis that is difficult for me because it’s mostly extremely high register, which involves a lot of lip pressure and I’m getting old. I am also preparing to conduct my own piece ‘Kryptoplégma’ at the same concert. It’s quite a wild piece for trumpet and clarinets (including contrabass) and double basses and electric guitars.

Then I want to arrange some concerts in 2024 for Konk Pack, my trio with Thomas Lehn and Roger Turner, as we have reached our 25th birthday as a trio and we’ve decided to celebrate that event permanently from now on. There is also the Henry Cow improvising project. We have the two concerts in Czechia that you know about, and one further concert in Barcelona with Annemarie Roelofs in January, and after that, I don’t know. My next concert is probably with Atsuko Kamura at Club Integral in London. She plays keyboards and electronics and has a very distinctive voice and seems to draw her pitching from traditional Japanese musics. I am also thinking about setting some Haiku for her to sing. Today I attended a rehearsal with the group UT, who are a long-time favorite of mine: their songs are always delivered with absolute commitment and they are like emotional diamonds. We played in Salford recently to a very young audience and I’m glad to say that no one knew or cared who I was.

What would I recommend people to listen to? I’m very proud of the CD that I produced last year of pieces by Annamaria Avram and Iancu Dumitrescu performed at the Sacrum & Profanum Festival in Krakow by the Hyperion Ensemble. These are very varied pieces and the last piece by Iancu is really extraordinary. The CD is ‘Sacrum et Profanum,’ Avram & Dumitrescu, MN2201, available in all good record shops and from ReR Megacorp. Music that I’ve found exciting and interesting lately has included Joe Harriet’s early freeform albums made around 1960, and comparable with Ornette’s work. Also, Yuja Wang performing the well-known piano concertos by Rachmaninov, Prokofiev, etc.—a kind of music that I had never previously listened to but which is given a special uplift by this extraordinary player whose entries and exits are always incomparable. What else: a CD called ‘Six Hands at an Open Door’ by the Langham Research Centre with John Butcher. (I heard this trio live augmented by Sharon Gal on vocals recently and it was a highly memorable gig.)

Klemen Breznikar

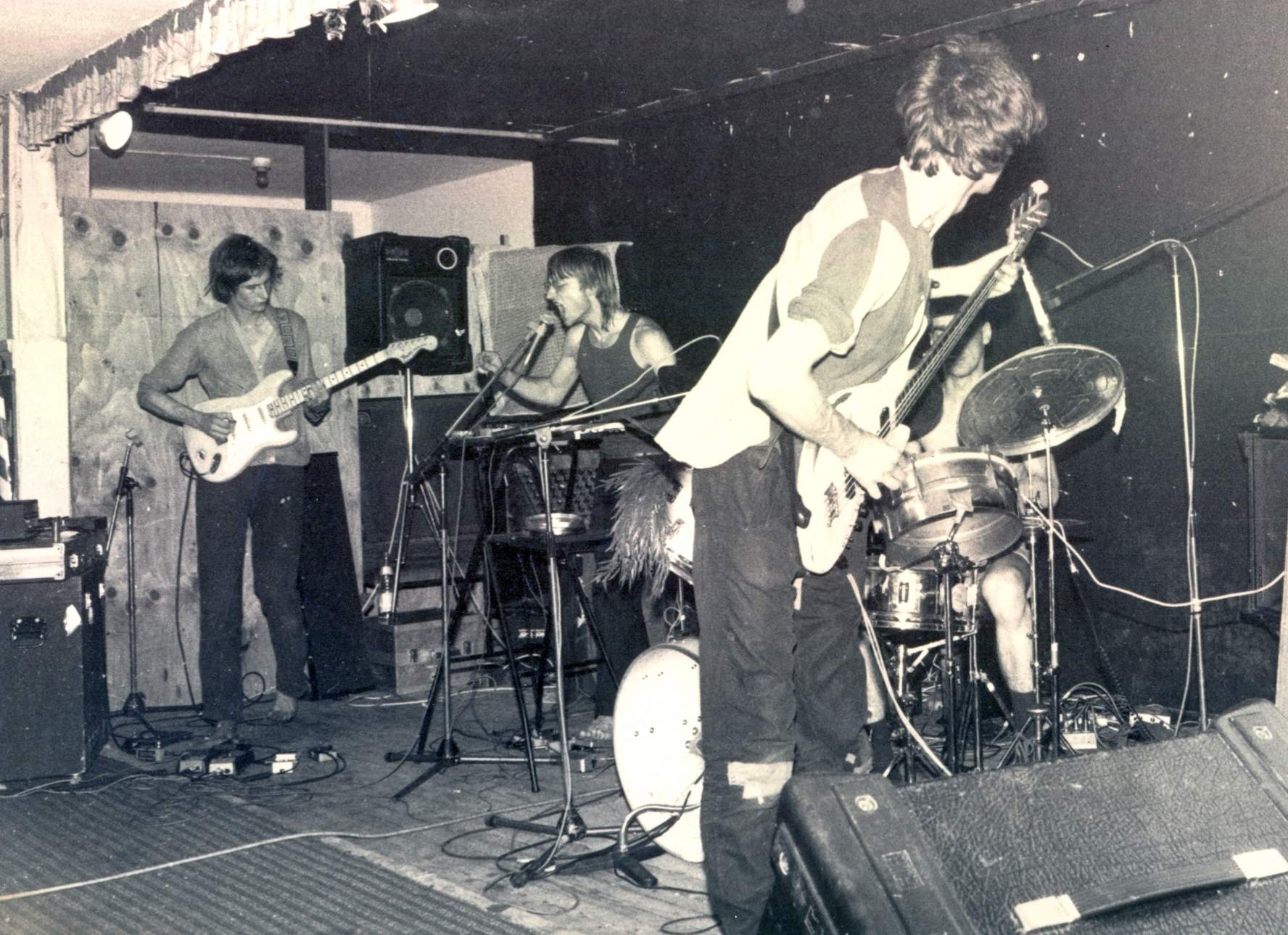

Headline photo: Henry Cow, Walmer Road (1970’s)

Tim Hodgkinson Official Website / Bandcamp

Ken Hyder | Talisker | Interview

Fred Frith interview about Henry Cow & beyond

Chris Cutler interview about Henry Cow, Art Bears, Cassiber…