Marlon Cherry | Interview | New Album, ‘Fever Dreaming In Lo-Fi’

Marlon Cherry, a versatile multi-instrumentalist and songwriter originally from North Carolina, has been an underground figure in the New York City music scene for decades. Cherry’s latest album, ‘Fever Dreaming In Lo-Fi,’ marks his fifth solo release.

Known for his work with groups like Anti-Seen, Afro-Jersey, and The Roches, Cherry’s expansive career includes collaborations with Tony Award winners Stew & The Negro Problem, Terre Roche, and many others. His solo projects have been released by labels such as Fang, Regina, and OSR, showcasing his diverse style. ‘Fever Dreaming In Lo-Fi’ offers an eclectic mix of Dream Pop, Jazz, Experimental, World Beat, and a touch of A Cappella R&B, highlighting his broad range. Following his previous project, Cherry continues to blend genres in innovative and unexpected ways.

“A constant journey towards inner peace”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Marlon Cherry: I was born and grew up in Charlotte, North Carolina (southeast United States for those not familiar). I lived with my father and grandmother. My mother lived in NYC, and I got to visit her during school breaks, which is when I fell in love with the city that is now my home. In my early teen years, I was torn between wanting to be a basketball player and a musician. Music won out when my older cousin started a band and drafted me as the bassist, even though I didn’t really know how to play at the time. After a few months, we were actually good enough to play for local high school dances, performing funk and R&B covers from Earth, Wind & Fire, Ohio Players, Funkadelic, The O’Jays, Stylistics, Isley Brothers, etc. That’s when everything changed. Before that, my daily life was pretty bland. The neighborhood that I grew up in was modeled after the whole American Dream aesthetic depicted in television shows of the ’50s and ’60s, even though it was an all-Black neighborhood, as Charlotte was very segregated at the time. It wasn’t a ghetto, but it wasn’t upper class by any means. I would describe my family’s status as lower middle class, but we had a pretty decent house, as was typical of the neighborhood. My friends’ parents were teachers, policemen, clergy, laborers looking to better their lot, and a few business owners, most of those businesses being restaurants or barber shops. I went to school, came home, did my homework, and went out to frolic with friends in the area. Once the band became known, I suddenly became kind of popular, especially since all the other guys in the band were a bit older than me. I was 13 and still in junior high, and they were all in high school. So I was being exposed to things a little beyond my age, because they were already emulating the whole sex, drugs, and rock and roll lifestyle that everyone thought musicians were supposed to live. The band rehearsals usually ended up turning into a party scene. This did not sit well with my father. By the time I was 17, the band had broken up, and I was getting interested in other types of music, but it was a great way to get started in the world of music.

Was there a certain scene you were part of, or perhaps you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend many gigs back then?

There wasn’t any real scene at the time, or if there was, I certainly wasn’t aware of it. I had seen a ton of gigs very early on, and it was all the great Black groups of the time. I saw James Brown more times than I can count. He played Charlotte a lot. Also, my best friend’s father was a policeman who worked the shows that came to the big arena, so he got us in to see a lot of shows by all of the bands that I mentioned earlier. When I visited my mom in NYC, she would take me to shows at the Apollo Theater, which was mind-blowing. One memory that I’ll never forget was her taking me there to see Stevie Wonder in the middle of an afternoon, because at the time, the performers often did matinee shows as well. I didn’t go to my first rock show until I was 14. I’ll never forget that either. Robin Trower came to Charlotte when his ‘For Earth Below’ record came out, with Golden Earring as the opening act. They played at a place called Park Center, which was basically the gymnasium where the local college basketball team played. I vividly remember walking in and seeing all these white hippies, a few Black hippies, and the overpowering smell of weed. Everyone was having a great time. I was in heaven. Both bands were great! From then on, I went to almost every rock show that came to town. I was hooked. Unfortunately, Charlotte wasn’t a big tour stop for a lot of major rock acts at that time, which meant having to take road trips to Atlanta, Georgia, to see some shows.

If we were to step into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters, etc., would we find there?

I remember my teenage room well. I had a blacklight and a couple of blacklight posters. I was trying to be as rock and roll/hippy as possible. Posters included Hendrix, Jeff Beck, The Edgar Winter Group, Chicago, Pink Floyd, Joni Mitchell, Kiss, Bowie, and Keith Richards, as well as the album covers from the film ‘Tommy’ by The Who, Betty Davis’ ‘They Say I’m Different,’ and Funkadelic’s ‘One Nation Under a Groove.’ My family had a bit of a hard time understanding why there were so many white guys on my wall. They never gave me a hard time about it though. I spent a lot of time in that room learning bass parts to my favorite songs.

Could you share with us your journey into music and how you became involved in bands?

After my cousin’s band broke up, I met a guy named Billy James, who played drums. We hit it off as music fans, and he turned me onto a lot of great music, a lot of prog and jazz rock fusion. We started playing together and ended up forming a band that lasted only a few months, but it was a friendship that still exists to this day. Eventually, we played in another band together called Lazy Lightning, covering Grateful Dead, Rolling Stones, Neil Young, and the like, until he eventually left to go to school at Berklee. That experience got my name and reputation as a fairly good bassist exposed in a couple of music circles in Charlotte.

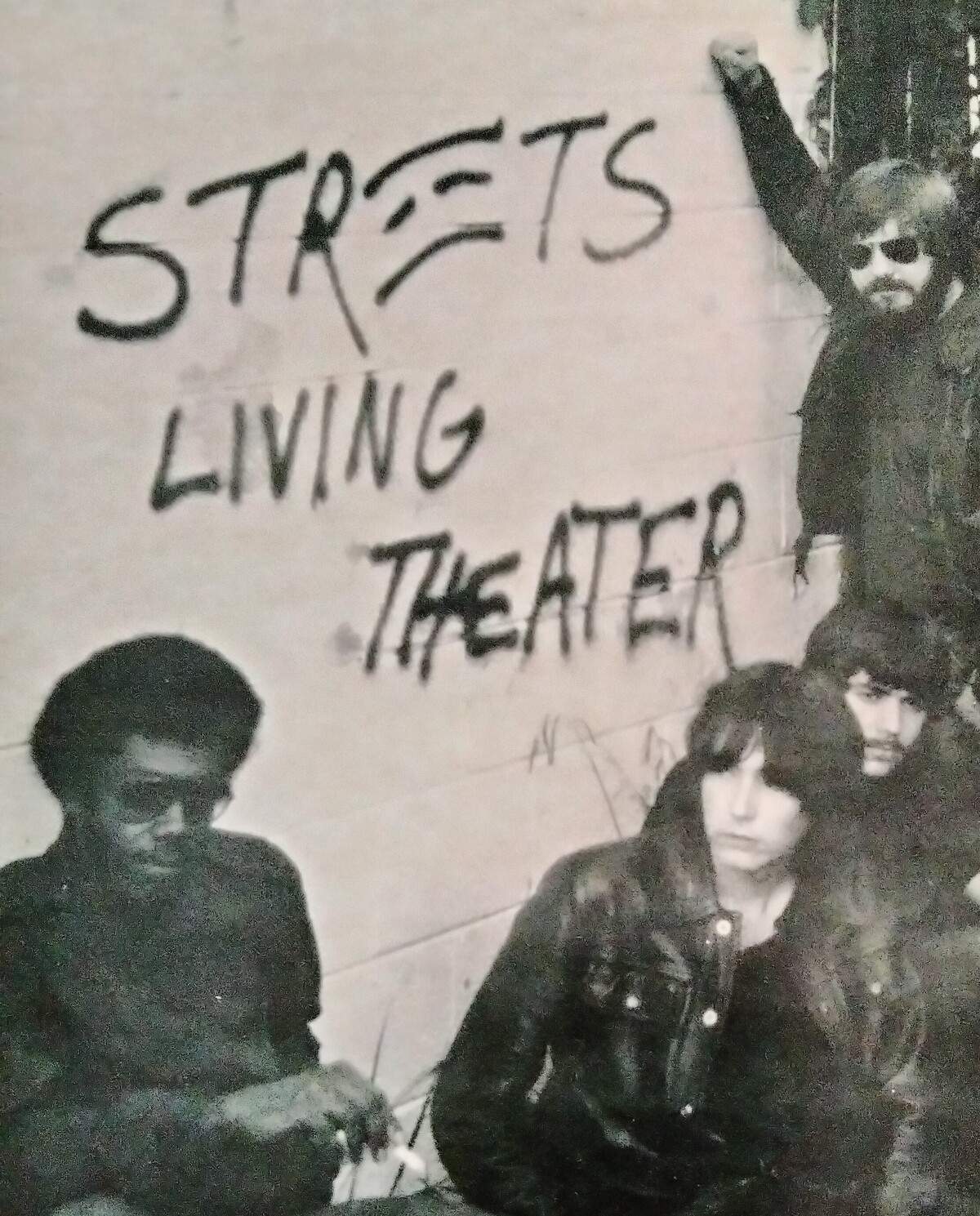

One of the first bands you played with was The Streets Living Theatre. The band released an LP via Stendec. Could you tell us about it?

The Streets Living Theatre already existed, known at the time simply as The Streets. I met them through Billy and the Lazy Lightning crowd. Their guitarist was leaving the band, and I auditioned and got the gig. Even though I was really a bassist, the music they were playing seemed easy enough for me to pick up on guitar. Aside from their original music, they were covering songs by The Doors and The Velvet Underground, which were their two main influences. It was the beginning of my experience as a guitarist, and I loved it. We developed a nice following locally and eventually regionally.

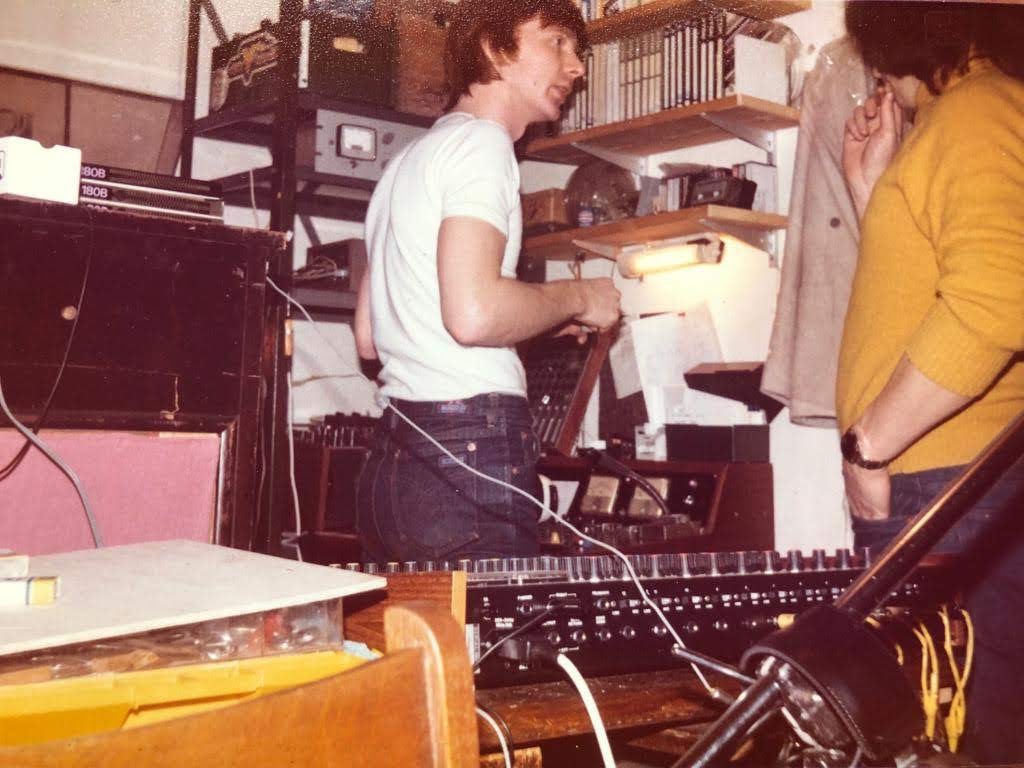

When we were ready to make a record, Mitch Easter had become the go-to guy in North Carolina for recording and producing, due to the success of his work on those early R.E.M. records. His studio was only a couple of hours’ drive away in Winston Salem, and we were lucky enough to get him to do the record. It was another mind-blowing experience. I was a big fan of his band, Let’s Active, who we got to open for a few times. Watching him in action behind a recording console was just as exciting to me as watching him play guitar. We had a blast making that record. It was done very quickly, in about two or three days, because Mitch had another band coming in right after us. He was extremely busy at that time. I’m really happy to have that be the first record that I played on. I actually played sax on one of the songs, called ‘My Baby Don’t Care.’ That was fun, but I haven’t touched a sax since then. When we sent the record to be mastered, we got a notice that Steve Walsh, the keyboardist from the band Kansas, was putting out a solo record under the name The Streets, so we changed the band name.

How did you join Antiseen, and on which of their recordings can we hear you play?

When I joined Antiseen, it was understood that it would be temporary because I was planning to move to NYC. But the move was about a year away, and they needed a bassist. I had been a fan of the band and friends with them for a while, and it seemed like it would be a fun thing to do before leaving Charlotte. I played on their ‘Royalty’ 7″ EP. A couple of those songs ended up on their ‘Honour Among Thieves’ LP, for which I’m listed as a co-producer along with Jeff Clayton. I was at the recording sessions for that one, but I don’t recall doing anything deserving of that credit. I was just there as a sort of moral support. I probably helped them most with loading gear in and out of the studio on that one.

What would be the craziest gig you did with them, and how would you describe the scene that the band was involved with?

There’s no one gig with them that stands out as being the craziest, because they were all pretty crazy. They had built up a pretty big following, and the fans just wanted to release their energy to match the band’s energy, which was very intense. It was that energy that made those shows so much fun to play. Jeff Clayton used to cut himself on stage—a bit of professional wrestling showmanship influence. I remember waking up the morning after a few gigs and seeing Jeff’s blood on my sneakers. That became normal. The punk scene in Charlotte and the surrounding areas at that time wasn’t very big, but it was that amazing energy that made it seem bigger than it actually was. Everyone was so young and excitable, and it felt like we were all getting away with something taboo in the conservative South. That seems typical of every youth generation past and since, a sort of rite of passage thing.

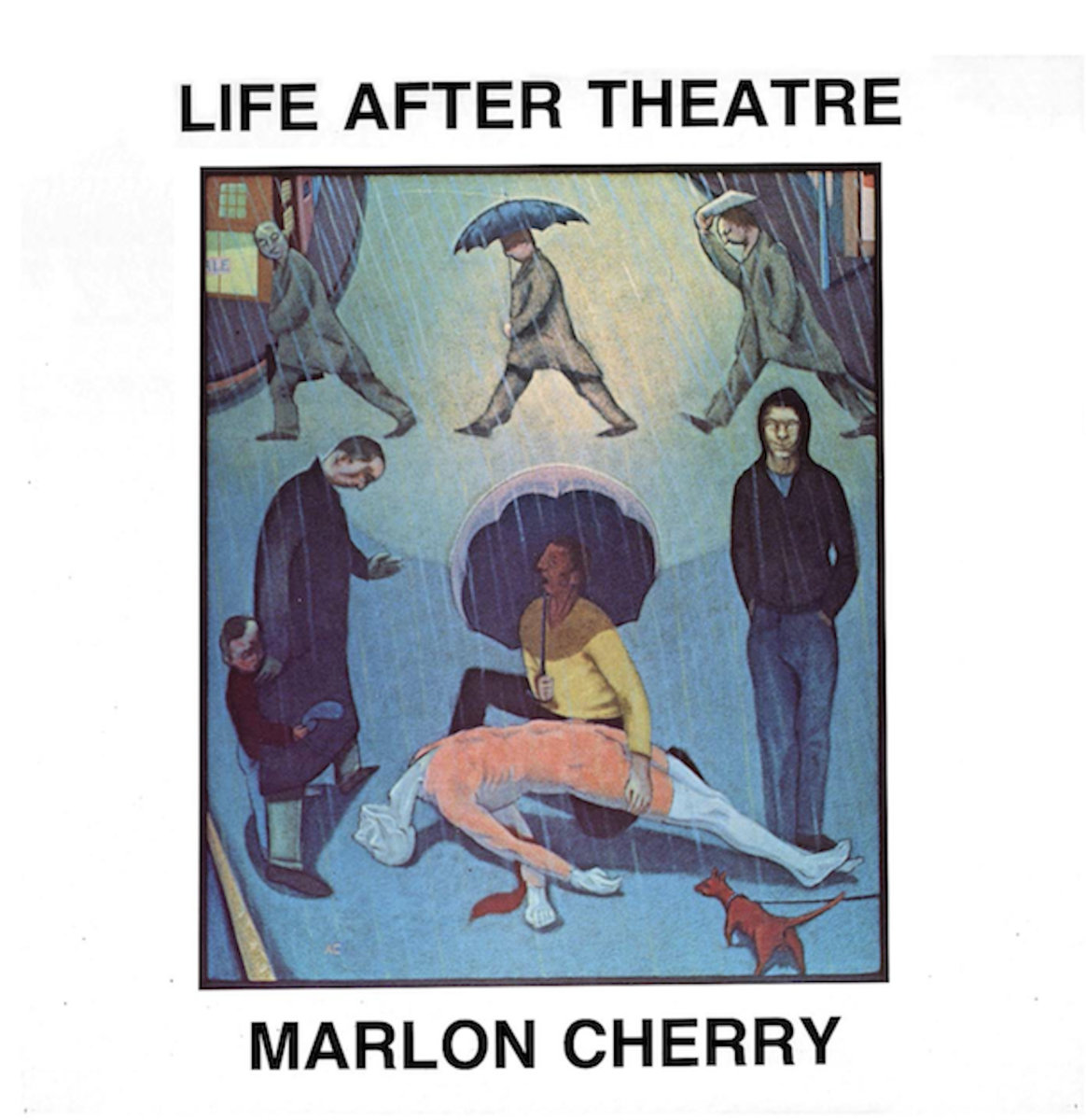

How did your self-released record, ‘Life After Theatre,’ come about?

‘Life After Theatre’ came about before I joined Antiseen. I had played in a psychedelic garage band called Life After Death right after leaving The Streets Living Theatre. We recorded a couple of cassette-only releases and a 7″ single. At the time, I felt like I wanted to stretch out into new musical territory and started feeling really restricted by the idea of being in any band situation and having to live up to some kind of musical persona, so I left that band and started developing my own material. The title is a direct reference to me leaving both of those bands in order to have my own artistic life. I was a bit surprised by all the positive responses that record received. I still get a lot of positive feedback about it. A few years ago, it was finally released on CD format along with the ‘Pete’ album. Zach Phillips, who engineered and co-produced my new record, is responsible for that.

“I was heavily influenced by guitarists Andy Summers and Robert Fripp, drummer Bill Bruford, and the textures of Brian Eno’s music.”

Would you mind sharing further insight on the writing, recording, and the concept behind ‘Life After Theatre’?

Immediately after I left ‘Life After Death,’ I had a sudden flood of ideas for songs and instrumental pieces, but there was no set concept for the ‘Life After Theatre’ record. I knew that I was going to play all the instruments and do all the vocals, so I chose the pieces that I felt most comfortable with in terms of that. That’s why it ended up being an EP rather than a full-length LP. The writing process for the record started with the music. At the time, I was heavily influenced by guitarists Andy Summers and Robert Fripp, drummer Bill Bruford, and the textures of Brian Eno’s music. I didn’t have a drum kit to work out parts on, so I established the basic grooves with the drum setting on a very cheap Casio keyboard, and then I would practice the kit playing by playing air drums over those grooves. I cracked myself up a few times doing that. There were moments when I realized how silly I must have looked, pretending I was playing an actual drum kit. The lyrics all came after the music, and in a couple of cases, the arrangements were altered to fit the lyrics. The recording process ended up being a lot easier than I expected, probably because I really knew exactly what I wanted when I went in. The recording took place at Audio Inc., a small studio run by Frank Rogers that was mostly used for recording commercial jingles. Jeff Murdock, my old bandmate from The Streets Living Theatre, did the engineering. We did all of the recording over two evenings, then went back a couple of weeks later and mixed the entire EP in one session.

What can you tell us about the cover artwork?

The artwork for the EP is a painting by my old friend, Alex Clark. I really loved his work, and once I saw that one, I felt it was a perfect fit for the title. He also did the painting that was used for the Streets Living Theatre album cover, and years later, I chose one of his pieces for my ‘Elsewhere’ CD cover. Sadly, we lost touch with each other over the years. I certainly hope he’s still alive and well.

How many copies did Regina Records press? Could you also provide more information about Regina Records? Did you play any gigs featuring your songs?

It was a totally DIY project, so I was also Regina Records. I chose that name because it’s the middle name of the woman I was married to at the time. She was extremely supportive of my endeavor, and it was my way of showing gratitude to her. The initial pressing was 1,000 copies, which I didn’t expect to run out of, but I ended up running out and did a second pressing of 500. I only have one copy for myself, as well as the test pressing, so I was really happy that Zach wanted to do the CD release a few years ago and pair it with the ‘Pete’ album, all on one CD. I didn’t put together a group to perform any of the material live. In fact, I only put a group together for a live performance of my solo work once. It was such a headache that I abandoned ship after two gigs. I’m very happy to have my solo work be studio projects and leave them at that.

The material is very diverse… Can you tell us about it?

I never gave any thought to the diversity of the material. I just knew that no one else in the area at that time was doing anything in the vein that I wanted to do for my own record. R.E.M. had started to get really big at that time, and a lot of bands were jumping on that train sound-wise, and most of the bands that weren’t doing that were doing something that was easily identifiable musically as Southern in influence. Aside from being a huge Todd Rundgren fan, I was really immersed in the current crop of Brit Pop like The Cure, Echo & The Bunnymen, Bauhaus, The Smiths, a lot of the 4AD label stuff, etc., and I was also into the 80’s version of King Crimson and listening to a lot of older jazz at the time.

What about Intensive Care?

There’s really not much to tell about the Intensive Care records that I played on. I was basically a session guy for those. It was around the time that I was making plans to move to NYC, so my mind was mostly occupied with that. I honestly don’t even remember the recording sessions. I haven’t listened to that stuff since I left Charlotte, but I do remember that when I did listen to it, I didn’t think my playing on them was good.

In 1990, you released ‘Pete’. We’d love to hear the story behind it and how you would compare it to your 1986 recording of ‘Life After Theatre’?

After living in NYC for two years and still not having found a band situation nor any artistic circle of friends that I felt comfortable in, I decided to undertake another solo project, doing the totally DIY thing again. Once I had enough material and finances, I booked studio time at Calliope in midtown Manhattan. I was working on a very low budget and I got their cheapest rates, which meant all of the sessions started at midnight and ran until 6:00 am. There were 3 recording sessions and 1 mixing session. The studio assigned Eddie EZ Reed as the engineer. He was actually more of a hip hop guy, but he did an excellent job with my stuff, and we hit it off really well. My feeling at the time was that the record would be a real goodbye to my life in North Carolina and to the South in general. When the recording was completed, I actually did shop it around to various indie labels, but nothing happened there, and I was resigned to putting it out myself. Then Adam Cohen of The Mommyheads introduced me to Chris Rael, who had started a co-op label called Fang Records, which was comprised of about 8 or 9 bands including The Mommyheads and Chris’ group, Church Of Betty. Several years later I became a part of that group. Chris agreed to let me become a part of the Fang co-op, which meant that I would still foot the bill for the record, but it would be part of packages that were sent to radio and print media that included various Fang artists. I loved the idea of that. It was very old school and felt really communal. I’ve never really compared that record to Life After Theatre except in terms of my own artistic and technical growth as a musician and songwriter. In that regard, I was very pleased to see that there had been some growth and that continues to be the criteria for me in terms of what I hope to accomplish with every next project that I do on my own and with other artists.

Mecca Bodega, Alpha Cat, Ancient Sound, Modern Dance, Zach Phillips, Lilith Outcome, and more recently Eszter Balint. We’d love to hear about these collaborations.

I joined Mecca Bodega as a guitarist in 1993, after having played on their first CD. I knew Marc Mueller from my time living in Charlotte when he was the drummer for the band, Fetchin’ Bones. (They were recently inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall Of Fame). He had moved to NYC and started the band with his brother, Paul. That’s the band that I spent the most time on the road with, playing clubs and Jam Band festivals across the US and a 6-week tour of Australia. We also did a lot of busking in the NYC subways, which led to us being seen by Jonathan Demme’s scouting team and being picked to do some music for a project that he was involved in with HBO. The project was an HBO Original film called Subway Stories, and we did the soundtrack for most of the film. The recording experience was fantastic. We got to work with various directors, including Abel Ferrara, Alison McLean, & Spike Lee (though Spike’s piece ended up being cut from the film), and Mr. Demme actually had us in the final scene of his piece. It was the publishing deal from that that gave me the opportunity to pursue music full-time. I left that band in 2000, again feeling the itch to seek artistic growth. I released my next solo project, ‘Elsewhere,’ shortly after that.

The Alpha Cat thing was another hired-for-the-session situation. I knew Elizabeth McCullough from the early Mecca Bodega period when she was dating the bass player. I really like that record. I only played bass on one song, but It was fantastic to get to play on it with the great Richard Lloyd on guitar.

Ancient Sound, Modern Dance was my next solo project. It came about from me becoming a dance class accompanist at a couple of colleges here in NYC and for the Paul Taylor School, where I played classes for 17 years until 2020 and was honored to get to know the legendary choreographer. The classes are in the Modern/Contemporary genre, so I get to do a lot of improvising, which led to me being very creative. Most of the music for that project was born of ideas that I came up with in those classes. I’m still playing for classes at Barnard College, currently in my 18th year there. As with the ‘Elsewhere’ CD, I recorded it in my apartment, using an old Roland unit that recorded directly to zip disc.

Zach Phillips asked me to be a part of his Lilith Outcome project during the time we were working on ‘Fever Dreaming In Lo-Fi.’ He’s a bit of a musical prodigy, and I honestly felt like some of his stuff was beyond my capabilities, but it was good for me to do something outside of my comfort zone and it certainly led to a bit of growth for me. I loved working with him and the crew of artists that he brought in for that. I also loved getting to sing on his How To Slip Away record. (I’ll cover Eszter Balint in one of the answers to another question below).

‘Fever Dreaming In Lo-Fi’ showcases a wide array of musical styles. Can you share some insights into your creative process when blending genres?

As far as blending musical genres, as on the ‘Fever Dreaming In Lo-Fi’ record, I stopped considering myself as a genre-based artist a long time ago and I just think of all of the various genres that I enjoy and am influenced by as just music. There was no real process in that regard when making the record, which is more akin to the ‘Elsewhere’ record, whereas with ‘Ancient Sound, Modern Dance’ I was focused solely on a world beat/experimental vibe. The two biggest influences for me, as far as genre blending goes, are Todd Rundgren and Paul Weller. Their solo output is all over the map in terms of genres, and they’ve both been really adventurous when it comes to having various genres on one record. They make it appear seamless. It makes the listening experience more like going on a journey through different worlds for me, and I really enjoy experiencing that in my creative processes.

How do you feel your music has evolved since your earlier releases, and what themes or ideas are you exploring in this latest album?

I’ve enjoyed the way my music has evolved over the years since the first couple of releases. With each new record, I’ve seen growth, both artistically and technically. Much of that has been influenced by the various artists that I’ve been fortunate to work with. I think the new record is certainly the most soulful of all of my solo output. There’s certainly the recurring theme of dreams and dreaming throughout. That wasn’t planned. Once I had all of the original material written, I noticed that the word “dream” appeared in some form in almost every song, and that was really appealing to me. I certainly wanted the record to have a dreamlike quality. I put Brian Eno’s song, ‘By This River,’ on there because it seemed to fit that idea perfectly, plus I love his music.

Can you share any memorable moments or challenges you encountered while recording or producing ‘Fever Dreaming In Lo-Fi’?

The most memorable challenges of making the record concerned health issues. On the date of the very first session, I had a severe nosebleed on my way to the session. I found myself standing in a subway station with blood coming out of me like someone had turned on a faucet. I called Zach and told him that I couldn’t make the session. I went into a local emergency care facility, and they gave me some saline solution. About half an hour later, the bleeding had completely stopped. I called Zach again to see if he was still up for doing it since we’d both prepared for it. He said yes, so I went in and we recorded ‘Sleeptalking.’ Another thing throughout all the sessions was that I was having some serious dental procedures, and my mouth was in various states of disarray from one session to the next. For some reason, I didn’t consider how that would affect my singing. That made recording the vocals very adventurous and at times extremely humorous. Then when Terre Roche came in for the session for ‘Blessings,’ she was still overcoming the effects of a bout of vertigo. I told her that we could reschedule, but she was a real trooper and wanted to go through with it. I remember Zach and me watching her and giving each other looks of awe as she played. That’s why she is credited as playing Vertigo Acoustic Guitar. All my other memories of the sessions involve just how much fun Zach and I had in the studio.

You’ve collaborated with a diverse range of artists, from Stew & The Negro Problem to Terre Roche and Syd Straw. How has working with such varied musicians influenced your own musical style and approach?

Working with a diverse range of artists has been a great learning experience. It’s fascinating to see how each artist’s creative process differs, as each one takes a different route to the same destination—achieving their desired goal. From Terre Roche, I’ve not only learned musical and creative ideas but also important life lessons accumulated over years of knowing and playing with her. These lessons have proved invaluable when working with various personalities. I also had the privilege of working with her sisters, Suzzy and Maggie. Maggie, in particular, was a true musical genius, and I still feel in awe of some of the experiences I had with her, even since her passing 7 years ago.

Working with Stew & The Negro Problem has been like attending a really fun school. Stew has utilized me as a guitarist, percussionist, and vocalist, always pushing me beyond what I perceive as my limits at the time. Embracing the challenge of being under his leadership has led to significant personal growth. Then there are artists like Eszter Balint, Syd Straw, Chris Cochrane, and Chris Rael, whose material is more within my technical comfort zone, yet I still gain valuable influence and insight from collaborating with them, contributing to my ongoing evolution as a musician. I’m currently involved in projects with both Stew and Eszter, and I’m thoroughly enjoying the experience.

I’m part of the recent Stew side project, Baba Bibi, and I’m really proud of our recent release.

Could you tell us more about your experience working on music for film, theater, and dance? How does creating music for these mediums differ from composing for your solo releases?

What I love about creating music for dance, film, and theater is that the music plays a supporting role to a visual art form. It involves a different type of collaborative effort because you’re responding to visuals and movement rather than to the sounds of other musicians playing music. The challenge of coming up with something that fits in a complementary and enhancing way is truly exciting. There’s a rich history of work by some of the all-time greats like Bernstein, Morricone, Herrmann, Copland, Mancini, and more. I have deep respect for musicians like Hans Zimmer, Terence Blanchard, Danny Elfman, Stewart Copeland, Trevor Rabin, and anyone who regularly creates for those mediums. I’ve enjoyed the opportunities I’ve had to do that work, but it’s so different from composing for myself that I don’t actively seek it out. However, I did sneak in a bit of Bernstein’s ‘New York, New York’ with the little guitar swells at the very end of the song ‘Secret City’ on the new record.

Which instruments do you primarily play, and how do you decide which ones to incorporate into a particular song or project?

My primary instruments are percussion (which contains multitudes), guitar, bass, and voice. I’ve become competent enough to play some piano/keyboards, and I’ve recently started learning banjo and baritone ukulele. The decision about which instruments to incorporate usually depends on how they complement or fit with the instrument I start the composition with. If I begin composing a piece with percussion, it leaves room for any other instruments. If I start with a melodic instrument, there may end up being no percussion on it. Lately, I’ve been trying to minimize the number of instruments vital to a given piece, seeing how full I can make it sound with the fewest instruments. I’m always tempted to add more, but not just for the sake of playing every instrument I’m competent at. Now, I think in terms of textures and dynamic ebbs and flows relating to the piece.

Collaboration seems to be a significant part of your musical journey. How do you approach collaboration, and what do you believe makes for a successful creative partnership?

Collaboration has become extremely important to me. After hitting a wall with various band situations, there was a time when I didn’t want to collaborate with anyone to avoid aggravation that made the process unenjoyable. Then, I hit a wall by myself and started to aggravate myself. Once I started playing with other people again, it was a matter of only playing with people I enjoyed as both artists and human beings. For me, a successful creative partnership involves a certain amount of give and take, a great level of trust and understanding, and an allowance for other people’s egos, strengths, and limitations, as well as a desire to create something that is bigger than the sum of our individual parts.

Are you involved in any other bands, or do you have any active side-projects going on at this point?

Aside from my current work on projects with Stew and Eszter, I’m playing bass in a project of Chris Cochrane’s. He’s one of my favorite guitarists and has been a fixture in the NYC downtown avant-garde scene for a long time, working with people like Marc Ribot, Zeena Parkins, and Brian Chase (drummer for Yeah Yeah Yeahs), among others. We’re planning to do some recording at some point this year. I’d love to work with Syd Straw again. I had a blast being in the studio with her for Eszter’s “I Hate Memory” project and for the song she contributed to the recent Eric Andersen tribute album, ‘Tribute To A Songpoet.’ She lives in Vermont though, so it’s not a situation where we can just hang out and play whenever we want.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

I love listening to music and checking out unfamiliar music, both new and old. Some recent discoveries that have wowed me over the past few months include Don Letts’ ‘Outta Sync,’ PJ Harney’s ‘I Inside The Oldyear Dying,’ John Cale’s ‘Mercy,’ John Coltrane with Eric Dolphy on ‘Evenings At The Village Gate,’ The Dream Syndicate’s ‘History Kinda Pales When It And You Are Aligned,’ Sleater-Kinney’s ‘Little Rope,’ Janelle Monae’s ‘The Age Of Pleasure,’ Life In A Blender’s ‘Ben’t by The Weather,’ Andre 3000’s flute album (which is too long to name), the soundtrack to the film ‘Maestro,’ David Sancious’ ‘Eyes Wide Open,’ Ryuichi Sakamoto’s ’12,’ Dial & DeRosa’s ‘Keep Swingin,’ Nina Simone’s ‘You’ve Got To Learn,’ and The Rolling Stones’ ‘Hackney Diamonds.’ And while I’m at it, I love Keith Richards’ new version of Lou Reed’s ‘Waiting For My Man!’

What currently occupies your life?

In general, what occupies my life is recognizing how fortunate and blessed I am to be in this city that I love, making a living doing what I love with people I love, maintaining and nurturing this situation while seeking growth in my humanity and artistry, and enjoying and being grateful for the overall beauty and wonder of life. It’s essentially a constant journey towards inner peace that allows me to produce and inject positivity into those I come into contact with and the world at large. To that end, I’d like to thank you very much for doing this interview.

Thank you for taking the time to participate. The last word is yours.

Peace, Love, & Cheers!

Klemen Breznikar

Marlon Cherry Bandcamp