Wooden Wand’s James Toth | Interview | A Tribute to Bruce Cockburn: ‘Imaginational Anthem’

To celebrate Bruce Cockburn’s recent 79th birthday (May 27, 1945), James Toth discusses ‘Imaginational Anthem vol. XIII,’ which features a diverse constellation of artists honoring the renowned Canadian singer-songwriter and more.

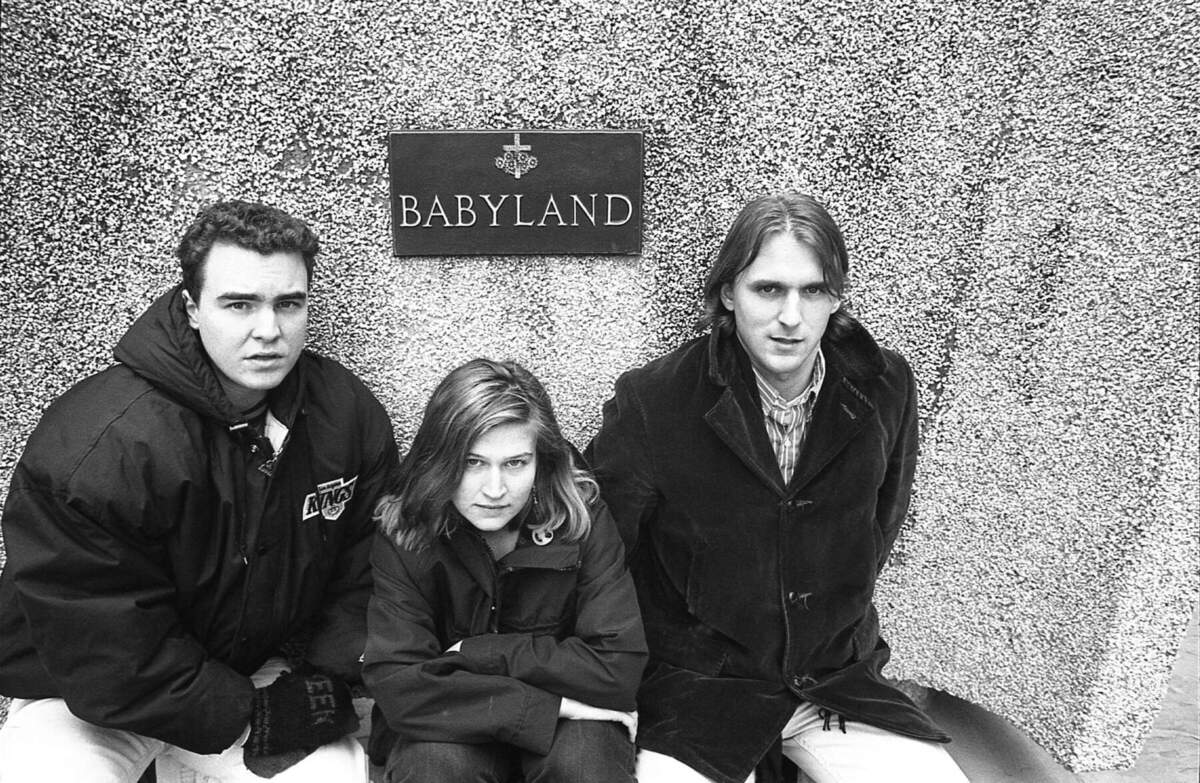

Released by Tompkins Square and curated by James Toth, known for his contributions to Wooden Wand, ‘Imaginational Anthem vol. XIII’ highlights Cockburn’s prowess as both a guitarist and songwriter. The album features a blend of instrumental and vocal tributes to Cockburn’s influential body of work.

“Bruce’s influence on my own music has been profound”

What led you to choose Bruce Cockburn as the focus for the 13th volume of ‘Imaginational Anthem’?

James Toth: The project was actually conceived by Josh Rosenthal, who runs Tompkins Square. His history with Bruce goes back decades, and I believe he even worked with Bruce and his manager, Bernie Finkelstein, professionally. Josh, a big fan himself, approached me after seeing my tweet about Bruce. Given our longstanding acquaintance and my admiration for his label, he asked if I’d like to curate the compilation.

How did you first hear about his music, and what does his music represent to you as an artist? How has Bruce Cockburn influenced your own musical journey, both as a guitarist and a songwriter?

I discuss this in detail in the album’s liner notes, but I discovered Cockburn’s music relatively late. It was sharing a bill in Canada with the band East of the Valley Blues that introduced me to his deeper catalog beyond the hits I knew as an American. The Cahill brothers, Patrick and Kevin, in that band, guided me to Cockburn’s early True North records. Upon returning from tour, I bought as many as I could find and became somewhat obsessed, as I tend to do!

As an artist, Bruce embodies integrity above all else. Like many of my favorite musicians, he eschews compromise and follows his artistic vision, regardless of trends or expectations. What I also find remarkable is his dual excellence as both an innovative writer and a proficient player, a trait he shares with icons like Prince, Willie Nelson, and Joni Mitchell. It’s a rare combination.

Bruce’s influence on my own music has been profound. For instance, inspired by his use of the mountain dulcimer on High Winds, White Sky, I purchased one myself and incorporated it into an album I released the following year.

How did you go about selecting the artists who contributed to the tribute album? Can you share any insights into the collaborative process between the featured artists, such as how they approached reimagining Cockburn’s songs?

I started with a wishlist of about 40 artists. My goal was to include as many Canadians as possible, so I began with them. I aimed high and reached out to some bigger names, leveraging mutual friends where possible. Two artists initially slated to appear had to withdraw: East of the Valley Blues had to decline due to a member’s health issue, and Doug Paisley couldn’t meet the deadline because of touring commitments.

Regarding how the artists approached their contributions, you’d have to ask them directly. I provided no specific direction or constraints, encouraging them to interpret the songs however they wished. I had complete confidence that whatever they created would be outstanding, and they did not disappoint.

What aspects of Cockburn’s music do you think resonate most with musicians, even if he hasn’t received as much attention from younger generations compared to other Canadian artists?

I believe it varies from musician to musician, which is fundamental to Bruce’s appeal. A guitarist could spend a lifetime studying Bruce’s tunings, phrasing, and guitar techniques without fully appreciating his exceptional lyrical prowess. Conversely, a lyricist might delve deeply into a song like ‘Pacing The Cage,’ a masterclass in songwriting, without fully recognizing Bruce’s supernatural guitar abilities. Beyond his musical prowess, younger artists might be inspired by Bruce’s global perspective and commitment to social change. While I’m not particularly political in my own work, I admire how Bruce has used his music for positive impact long before it became fashionable to do so.

Were there any specific Cockburn songs or albums that had a significant impact on you personally?

The album ‘High Winds, White Sky’ holds special significance because it was the first of Bruce’s early albums I sat down and really listened to. I bought about five of his records on the same day, and just happened to play that one first. It was like that scene in the Wizard of Oz when everything goes technicolor: suddenly, I got it. So, that one will always be a favorite. By now, I’ve heard all of his records as well as most of his b-sides—like many music fans, I am somewhat obsessive—and I enjoy all of his work.

“These interpretations ideally encourage listeners to seek out the original source”

Each artist brings their own interpretation to Cockburn’s songs. How do you think this diverse range of interpretations adds to the appreciation of Cockburn’s music?

I think tribute albums often function as Trojan horses. The concept itself feels very ’90s to me, but it’s a format and strategy I fully support. Before playlists and algorithms, if you were born somewhere between the mid-’70s and early ’80s, like I was, there’s a good chance you first heard The Carpenters, Dead Kennedys, or even Neil Young through a tribute album featuring your favorite bands. Essentially, these interpretations ideally encourage listeners to seek out the original source.

Were there any unexpected or particularly memorable moments that arose during the recording or production of the tribute album?

Well, not memorable in a good way. I’ve already mentioned the health issues faced by my friend Kevin of East of the Valley Blues, which, aside from being shocking and upsetting, was a particular bummer for the compilation. Kevin and his brother Patrick were the ones who initiated my Cockburn journey, and their band was among the first I wanted on the album. Fortunately, Kevin seems to be recovering well, and if we decide to do a volume 2, I’ll definitely reach out to those guys again!

As someone deeply involved in both indie and folk music scenes, how do you see Bruce Cockburn’s legacy evolving in the context of contemporary music?

It’s difficult to predict. While I’d like to envision a renaissance, I must candidly mount my soapbox here—achieving the level of renown that Bruce and his peers enjoyed in the 70s and 80s seems unlikely today. Our culture is too fragmented and atomized for future Beatlemanias. In 2024, most musicians struggle to make a living, largely due to exploitative platforms like Spotify.

That being said, I hope compilations like this one continue to introduce new listeners to the artistry of figures like Bruce.

Let’s discuss how you originally got into music. Can you tell us about your early experiences with music and how you were initially drawn to it?

Well, I actually have an entire podcast dedicated to this! It’s called The Toth Zone, exploring how music has influenced nearly every decision I’ve made, for better or worse. To quote the podcast’s tagline, it has given me a reason for living and has occasionally wrecked my life. Simply put, I can’t recall a time when music wasn’t profoundly important to me. From my earliest memories, and according to my parents’ accounts even before then, music has been the singular focus of my life. That remains true to this day. If you have no interest in music—any kind of music—I’d likely be the most boring person you could meet.

Who were some of your earliest musical influences, and how did they shape your approach to music?

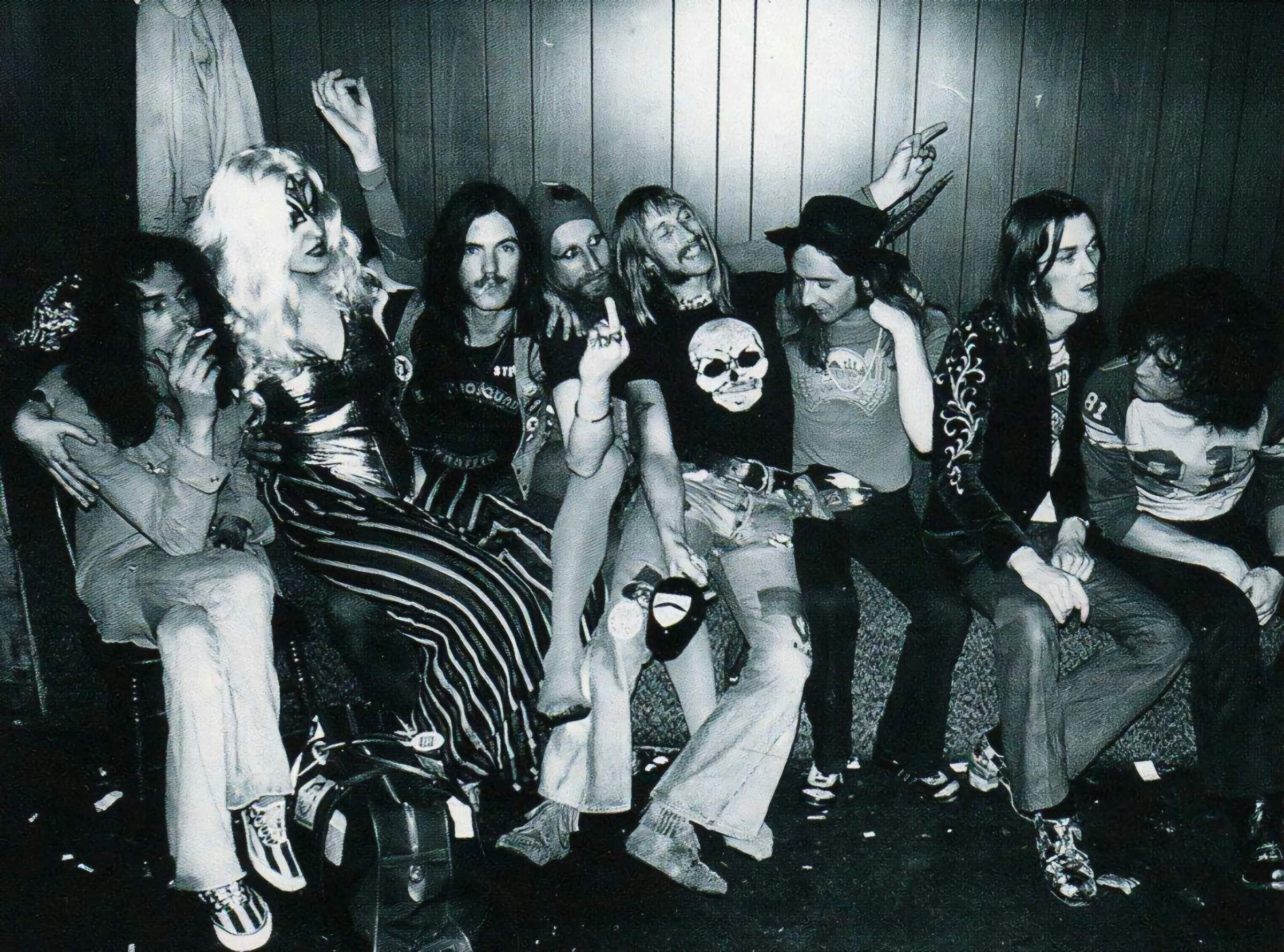

My first musical loves were heavy metal and hip-hop, both of which were omnipresent in my family and neighborhood. Growing up as an MTV kid, I absorbed everything from Skid Row to Phil Collins during my pre-teen years. However, metal and rap became the most significant influences on the music I eventually created, despite seeming unlikely to a casual listener. Rap music taught me the importance of lyrics and how to employ techniques like similes and metaphors to highlight impactful lines. Surprisingly, rap was more influential to me as a lyricist than even Bob Dylan or Leonard Cohen. Through metal, I developed a fascination with themes from the darker aspects of human experience, inspiring me to explore taboos. To clarify, my childhood was relatively happy with no significant rebellions, but I’ve always been drawn to the eerie, profane, and transgressive—I still enjoy drawing pentagrams and upside-down crosses on things. Ha!

How did your upbringing and environment influence the music you created, both in terms of style and concept?

As mentioned earlier, growing up in New York may have made me take things for granted initially. However, traveling extensively throughout the US and abroad made me appreciate how fortunate I was to have access to such diversity. Additionally, having a cousin in a popular heavy metal band showed me early on that making a career in music was possible, even from our working-class background.

If we stepped into your teenage room, what records, fanzines, posters, etc., would we find?

Between ages 10 and 12, my room would be filled with Iron Maiden, Mercyful Fate, and Celtic Frost. From 13 to 15, it would be dominated by hip-hop 12”s, as it was a golden age for rap music. By ages 16 to 17, I was deeply involved in the punk and hardcore scene, particularly with art-oriented bands like Indian Summer, Universal Order of Armageddon, and Ordination of Aaron. I left home at 17, so my teenage room was constantly evolving with new influences!

“The fundamental idea behind forming Wooden Wand was simply to reflect whatever intrigued me at the time, particularly private press psych folk records”

What inspired you to form Wooden Wand, and what was the vision behind the project when it first started?

These are challenging questions to address comprehensively, but the fundamental idea behind forming Wooden Wand was simply to reflect whatever intrigued me at the time, particularly private press psych folk records, as well as artists like Comus and Sun Ra. Since 1996, the records I’ve released have all been thinly veiled love letters to my musical fascinations. Prior to Wooden Wand, I had two bands that followed a similar ethos: attempting to convey my musical passions and obsessions while maintaining a degree of ambiguity.

How did the band’s lineup come together, and what dynamics did each member bring to the group?

I’ve never actually counted, but I estimate there have been around 50 or 60 people who have passed through Wooden Wand over the years! I thoroughly enjoy collaboration, and while I acknowledge the benefits of a stable lineup, I believe that a revolving door approach keeps things dynamic and fresh. Each person contributed uniquely, and looking back, omitting any one individual would be akin to leaving out an ingredient from a cake.

Can you walk us through the creative process within Wooden Wand, from songwriting to arranging and recording?

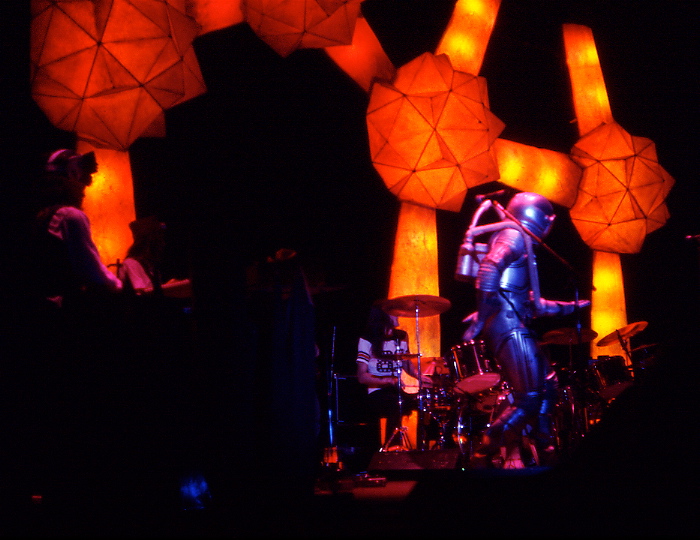

Most of the music I create is very instinctual. I typically don’t approach it with a specific plan, whether I’m crafting a collection of songs, collaborating with a drone or ambient artist, or simply experimenting for enjoyment. Sometimes, an idea, title, or opening line sparks inspiration, and I follow that trail of breadcrumbs. I’ve never struggled with putting something together, although not everything I create is necessarily meant to be shared. I don’t believe in writer’s block, or at least I feel fortunate never to have experienced it, much like boredom. Creating something has always been within my capacity and remains my favorite pursuit. This preference is also why I greatly prefer studio work to touring, although touring does have its merits too.

Wooden Wand’s music has been described as blending elements of folk, psychedelic rock, and indie. How would you characterize the evolution of the band’s sound over the years?

I think the only consistent thread is me. Primarily recognized, if recognized at all, as a songwriter, my own listening preferences and sources of inspiration are quite distant from what’s typically labeled as singer-songwriter music. Over the years, I’ve explored various musical styles, and sometimes I wish I could anonymously release albums to prevent people from imposing the baggage that comes with my history onto everything I put out. As the saying goes, you never get a second chance to make a first impression. Nevertheless, I’m grateful to have an audience, especially given the current circumstances.

Were there any specific albums or artists that inspired shifts in your musical style or experimentation with different genres?

Oh, I find inspiration anew every day! Creatively, I’m impulsive; I might overhear a compelling rockabilly record and suddenly feel the urge to acquire a hollowbody Gretsch and some pomade. Anything can become fodder for my creative process. Fortunately, I lack the proficiency on any instrument to faithfully imitate anything, so even if I set out to make a rockabilly album (which I haven’t—yet!), it would inevitably be filtered through my own idiosyncratic, untrained approach. Despite my efforts, only I would likely perceive it as a rockabilly album. Ineffectiveness can thus be advantageous!

In addition to Wooden Wand, you’ve also released music under your own name and collaborated with other artists. How does your approach to songwriting and performing differ between these projects?

Sometimes a new approach seems to call for a different moniker. Other times, it involves a specific project with particular collaborators, necessitating some form of distinction. However, it’s also enjoyable to wear many hats. Career-wise, it might have been more advantageous for me to settle on one “brand,” as many collaborators have suggested over the years, but as I mentioned, I’m restless.

For example, my band One Eleven Heavy has been together since 2017 despite the odds—none of us live within 500 miles of each other—and we’re planning to record our fourth album this summer. When preparing for an album, I focus on writing songs that best suit the band’s strengths and dynamics.

On the other hand, my DUNZA project is strictly solo, allowing me to experiment in ways I wouldn’t in a group setting. It also gives me unlimited time to concentrate, contemplate, and obsess over details that I might overlook or consider less important when working with a band.

Each Wooden Wand album seems to possess its own unique identity and narrative. How do you approach conceptualizing and structuring an album from start to finish?

Albums typically begin with selecting a small group of songs—perhaps two or three—that harmonize well and seem to fit together thematically. I don’t initially set out to write for a specific album; rather, I write songs individually until a few emerge that complement each other. Then, I’ll often try to compose several others in a similar vein to see how they integrate. Since I’m constantly writing and recording, I don’t usually think in terms of albums until there’s a collection of songs that start to form a cohesive pattern. However, I’m also not the best judge of my own work, so I frequently defer to bandmates or label representatives to help decide. I’m not a control freak and am happy to delegate.

Can you share any anecdotes or stories behind the making of a specific album that you feel encapsulate the creative spirit of Wooden Wand?

Much of our best work has come from collaborations with other people. For me, making music is about communication; it’s not about self-expression or healing. The initial part of that communication, before reaching an audience of strangers, involves collaborating with other artists and the serendipitous outcomes that arise from creative minds working together on a project.

For instance, when I recorded demos for the album ‘Blood Oaths of the New Blues,’ released in 2012, I sent them to the band I had worked with on the previous album—this is my usual practice. Months later, when we gathered in the studio, the drummer Brad Davis mentioned he had brought a harmonium along on a whim. That sparked a conversation about albums we admired that featured harmonium, such as Nico’s and Hermann Nitsch’s works. The album was already heavily influenced by Coil (as evidenced by the song named after Jhonn Balance, a personal hero of mine), and the harmonium unexpectedly became the missing element; it became the cohesive sound that runs through much of the album. This wasn’t planned; the record might have been very different—and perhaps less successful—had Brad not brought that harmonium that day. Ultimately, the harmonium became the key that unlocked what the album was meant to be all along.

Looking back on your career with Wooden Wand, what do you consider to be the band’s most significant recordings? Are there any albums that hold special significance for you personally? If so, what makes them stand out?

My two favorite Wooden Wand records are ‘Blood Oaths of the New Blues’ and ‘Clipper Ship.’ The former, as mentioned, took on a life of its own and became something greater than I initially anticipated. ‘Clipper Ship,’ on the other hand, felt like the culmination of everything I believed I could achieve and closest to my vision for the record from start to finish. That’s why I’ve decided it will likely be the last record under that name. However, I’ve cherished every album I’ve released and hold fond memories attached to each of them.

Tell us about James & The Giants…

That project began when I rekindled my friendship with Slim Moon of Kill Rock Stars, whom I had recorded for back in 2006 and who briefly managed me. We discussed releasing something and went through a few demos. I had the idea for Jarvis Taveniereto produce, since Jarvis is one of my oldest friends and collaborators, and a guy whose ears I trust. We recorded that album over an extended period, which isn’t my favorite way to work but was necessary due to our very busy and conflicting schedules, as well as the pandemic. I was very pleased with how it turned out, and I hope we can do another one.

“Everything in my life revolves around music”

What else currently occupies your life?

Everything in my life revolves around music. Most of my close friends are musicians, label owners, or record store owners. My wife is an English professor who publishes in sound studies, occasionally runs a record label, and releases music under the name amelia courthouse; we met backstage many years ago at a Wooden Wand show she was promoting. I have no hobbies. I do enjoy reading and watching films, but probably not any more voraciously than your average college-educated Gen X person.

I’m finishing up my first book, which covers many of the themes of the podcast. If all goes as planned, it will be published sometime in 2025. I also publish a zine called Head Voice with my friends Ben Chasny and Donovan Quinn, focusing broadly on unorthodox recording techniques. In between all of this, I occasionally do paid writing or copyediting work, mostly music-related.

At any given time of day, I am either writing, recording, reading about, listening to, talking about, or buying music. I never outgrew the obsession that many of us have in our formative years. I still get giddy walking into a record store. As Frank Zappa said: music is the best!

Let’s end this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you discovered anything new lately that you’d like to recommend to our readers?

Favorite albums and recent discoveries fall into two different categories for me. It may sound strange, but I rarely listen to my all-time favorite albums. Firstly, they’re all imprinted on my brain forever, and I can recall most of them in my head any time I want to hear them! Secondly, I don’t want to risk spoiling or diminishing their specialness. For me to sit down and choose to play a record like ‘Metal Box,’ ‘On The Beach,’ ‘Hejira,’ ‘Blood on the Tracks,’ ‘Disintegration,’ or ‘Wee Tam’ would have to be a special event.

As for recent discoveries: I’m really enjoying the latest album on ECM by Matthieu Bordenave, ‘The Blue Land’; I’m an ECM enthusiast and probably one of a handful of Americans who thinks the label has been releasing some of its best work over the past two decades. I’ve also been diving into the catalog of Frozen Border, a label that sadly seems to be defunct now, which deals in a very austere, brutalist, Sandwell District-inspired techno that I really like. The new Sleepytime Gorilla Museum album is awesome. I consider Autechre’s ‘NTS Sessions 1-4’ to be a pinnacle of human artistic achievement, and perhaps my favorite release of the decade. I’m also currently immersed in Jemeel Moondoc, especially the 3xCD ‘Muntu Recordings’ set on the No Business label out of Lithuania. Of course, I always find myself returning to Zappa, Peter Laughner, Coil, Sonny Rollins, Wet Tuna, Wire, Basic Channel, Stones, Dead, Funkadelic, Ornette, Wu-Tang, Arthur Russell, Keith Hudson, and anything from the Wackies label, as well as King Crimson.

Thank you. The last word is yours.

Thank you for the interest and support, and I hope everyone enjoys the compilation!

Klemen Breznikar

James Toth Instagram / Bandcamp

Tompkins Square Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / SoundCloud / Twitter / YouTube / Bandcamp