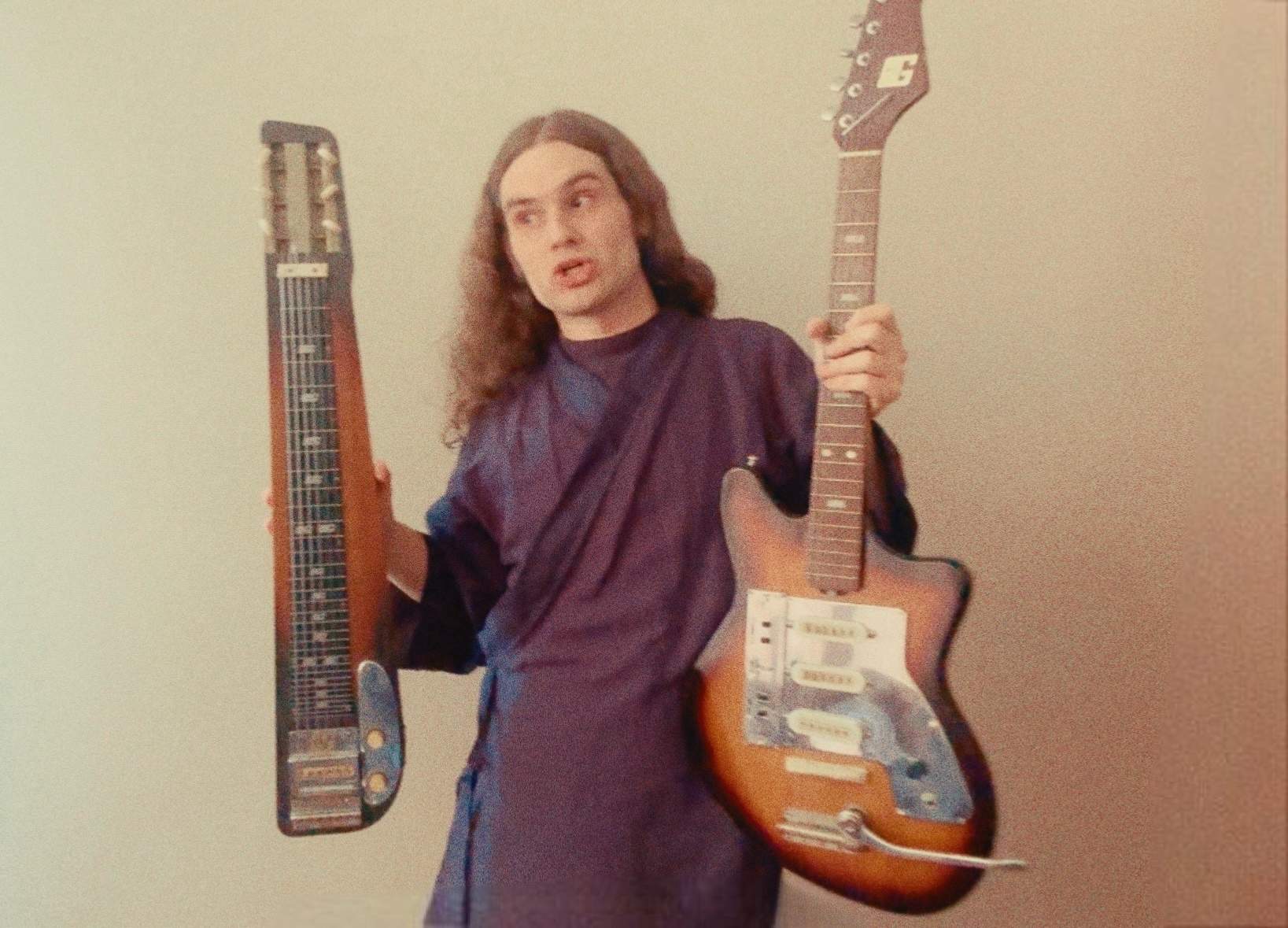

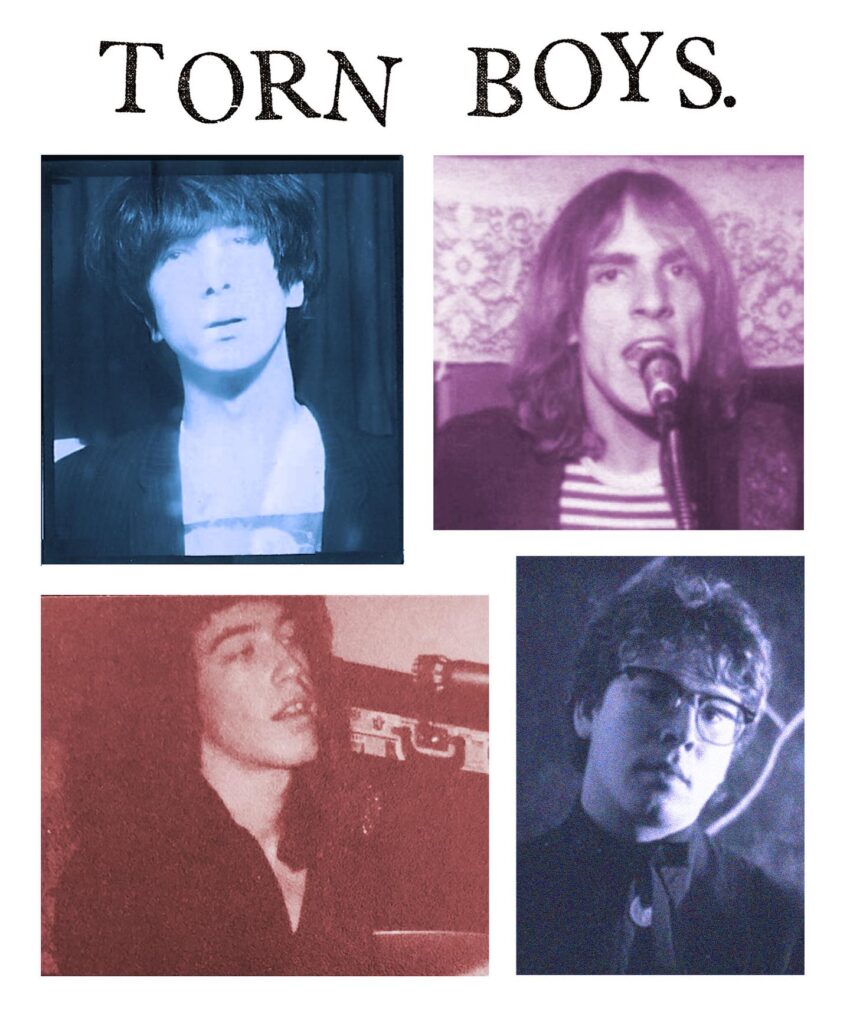

Jeffrey Clark and Kelly Foley discuss the Torn Boys

Emerging from the vaporous mists of Stockton’s music scene, ‘1983’ assembles the Torn Boys’ fleeting but feverish output—a mix of studio gems, lost singles, and curious relics.

Formed by Jeffrey Clark and Kelly Foley in late ’82, the band quickly became a cauldron of neo-psychedelic mayhem, blending dreamlike lyrics with syncopated synths and fractured guitar riffs. Their brief existence, from intimate cafes to raucous live shows, was a quest for sound and vision that slipped through the cracks like morning fog. As the band morphed and expanded, including the addition of Grant-Lee Phillips, they left behind a unique legacy—neither fully New Wave nor strictly art-punk, but a nebulous concoction of both. Now, decades later, 1983 resurrects their mythic, genre-defying essence, offering a glimpse into an elusive, audacious chapter of underground music, thanks to the ever-amazing and insightful Independent Project Records.

“Youth culture in the 1970s revolved so much around music”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Jeffrey Clark: I was born in Stockton, California, and for the first few years of my life, I grew up in a two-bedroom house on the west side of town. Chris Issac was an elementary school classmate of mine. When I was seven, we moved to a house with a big yard in a subdivision carved out of a walnut orchard. My upbringing was very stable, during an era pretty much like it’s depicted in the Mad Men television series. The world was changing rapidly, but for us, it was all on TV. I spent a lot of time with my nose in a book or immersed in listening to music. Or both. My mom, who grew up in rural Oklahoma, loved music, so by osmosis I absorbed deep, soulful stuff like Dinah Washington, Ray Charles, Kris Kristofferson, Ian & Sylvia, and King Curtis. Looking back on it, I had pretty eclectic taste for my age. At 15, I was very into Leonard Cohen as well as T. Rex. I listened intently to old Jefferson Airplane records but also to ‘Silver Dagger’ by Joan Baez and ‘Into the Void’ by Black Sabbath, etc. In a car radio at night, you could hear old doo-wop ballads played out of Tijuana. I lived inside my head a lot but also mowed the lawn on Sunday, played basketball in the driveway, and participated in similar suburban rituals.

Kelly Foley: I was born near Bakersfield, California, and we moved to Stockton when I was three years old. My mom’s side of the family was transplanted from Oklahoma, and though I was too young to appreciate it, my uncle Bill Woods is one of the founders of the Bakersfield Sound in country western music. Buck Owens and Merle Haggard played in his band. My older sisters were into The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Paul Revere and the Raiders, and The Doors, so I heard a lot of that as a little kid. I grew up in a construction business family and worked on building sites throughout my youth. My mom liked to paint, and I was always into art and drawing. Kids at school would ask me to draw. First, it was sports figures, “…draw Willie Mays”; then it would be “…draw John Lennon!” or “…draw Alice Cooper!” Jeff and I met when I was 14, through a friend who noticed our mutual interests. Namely, we both followed the Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, The Fugs, and the Firesign Theatre. So, dada-type absurd humor was a place where we connected.

What was life like in Stockton?

Kelly: Even though it’s more than seventy miles inland from San Francisco Bay, Stockton is actually a port city, with a river delta just to the west. So when I was a kid, my dad and I would wander through dockside saloons and see Russian sailors on leave from big cargo ships and trawlers. Because of the amazing soil and farmlands, you could drive out to the roadside stands in the summer and buy freshly picked fruits and vegetables. Once in a while, my parents would rent a houseboat for the whole family and be gone for a week down the Delta waterways. In my mind, it remains a beautiful pirate haven, and we adore it.

Jeffrey: At that time, Stockton was a city of about 100,000 people. It’s in the Central Valley of California, so it’s very flat, surrounded by farmland, orchards, and levees. Summers were hot and cloudless; winters were shrouded in fog. There were no real museums in Stockton and not much exposure to art or culture beyond what was on TV. There is a small university in Stockton, and when I was seventeen years old, I wandered into the Student Union to see Bergman’s Persona, which absolutely blew my mind. So you had to seek out whatever sources of light you might find here and there, and you paid attention, looking for potential peers. Stockton had great Mexican restaurants, thrift stores, and a very bleak skid row that you can get a glimpse of in the John Huston film Fat City.

Was there a certain scene you were part of, maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Jeffrey: Youth culture in the 1970s revolved so much around music, and though there wasn’t much happening in Stockton per se (well, I did catch a gig by Sandy Bull at the UOP Student Union one autumn night), we lived close enough to San Francisco to make it to concerts by major artists touring the West Coast. For a twelve-dollar ticket, you might see The Who, The Rolling Stones, Bowie, Blue Öyster Cult, Mott the Hoople, Neil Young. When I was 19, I moved to the Bay Area to attend college. The punk scene was hitting full stride at that time, and I found myself at incredible shows: Talking Heads for free in Sproul Plaza, the Sex Pistols, The Clash, X, Iggy, Devo, The Cramps, and on and on and on, along with all the Bay Area punk and post-punk bands of the day. Kelly and I saw Nico play her harmonium in candlelight at Mabuhay Garden in North Beach. That made what you might call an indelible impression.

Kelly: In Stockton, there was the Blackwater Cafe and Tower Records. The Blackwater was a cozy coffee bar/tavern that we (Torn Boys) co-opted pirate-like for our musical schemes. Any sort of art-kid scene was small but tight, so we would pack like-minded people into that little place. Passing through the Blackwater at any given time would be future members of Cake, Pavement, Chris Isaak, Groovy Ghoulies, The Authorities, Grandaddy, Black Flag, Moris Tepper, and later on, Chelsea Wolfe. Jello Biafra read poetry there, so it was that kind of necessary scene. And the Blackwater was where Jeff and I met Leslie Medford, who was performing solo material in the style of Roy Harper, Kevin Ayers, and Peter Hammill. That definitely caught our attention.

If we were to step into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters, etc., would we find there?

Kelly: The walls of my room were festooned with fold-outs and calendars from every rock music magazine: Creem, Circus, Trouser Press, etc. I listened a lot to ‘Raw Power’ (Stooges), ‘Too Much Too Soon’ by the New York Dolls, ‘Woofer in Tweeters’ Clothing’ (Sparks), Roy Harper, Joni Mitchell’s ‘Hejira,’ Sly and the Family Stone. And I was into Michael Mantler’s ‘Silence’ with Carla Bley.

Jeffrey: My bedroom was basically a little teenage shrine to some mysterious bohemian realm I aspired to and was sure was out there somewhere. I had undulating Op Art wallpaper, and on the wall above my bed was a big, black-and-white poster of Bob Dylan circa 1966 with a wild halo of hair and Ray-Ban shades. I had about three wooden crates to hold my precious vinyl LPs, one of which would always be spinning on my RCA Sears phonograph, and a collection of tattered paperbacks: Burroughs, Vonnegut, Fear and Loathing, etc. The Scaduto bio of Bob Dylan referenced some 19th-century poet called “Rimbaud,” so I tracked that down.

Were you in any bands before forming Torn Boys?

Jeffrey: While I was still at school in Berkeley, I was recruited by Kelly to be in a band in Stockton called The Mixers, which we lifted from A Clockwork Orange. We did covers of old Rolling Stones and Kinks tunes, and Nuggets-type stuff, and played in crummy downtown bars, local high schools, kegger parties—whatever. I’d never sung before, so being mostly an introvert and finding out I could do that was a bit of a revelation. For some reason, there often seemed to be a threat of violence at Mixers gigs; some hesher would get stoned on downers and try to take a swing at me while I was standing at the mic, or if a song request from the audience wasn’t met with due haste, a beer bottle or an ashtray would get flung up toward the stage—stuff like that. It kept you on your toes!

Kelly: I was in the Mixers with Jeff. We did British Invasion and American garage stuff like the Nuggets compilation by Lenny Kaye. I was also in a Pere Ubu-style collective named “CRLLL.” That band was started by some artist misfits led by Ed Dahl. They opened for the Dead Kennedys, and I was asked to join on bass. I later brought along a guy named Gary Young to drum.

Can you elaborate on the formation of Torn Boys?

Jeffrey: Kelly and I were always doing creative stuff as teenagers, basically for our own amusement, staving off boredom. We’d improvise absurdist sound collages on cassette tape or shoot these marijuana-fueled Super 8 movies. Later, when I was going to school in Berkeley, I began writing a few songs. Every so often, I’d drive down to Stockton, and Kelly and I would perform as a duo in local cafes. Just acoustic guitars; a lot of vocal harmony-type covers: ‘There She Goes Again’ by the Velvets, early Beatles songs, ‘Days’ by Television. We did ‘Mack the Knife.’ Once in a while, we’d try to work in one of these songs I was writing.

Kelly: I left CRLLL to pursue some dead-end rock bands I was singing with, but Ed (Dahl) and I also started recording in a project called DaDa 96, with our friend Duncan Atkinson, who’d just bought a synthesizer and drum machine. One night, Jeff and I were driving around in the valley, and I played him some of the DaDa 96 stuff, which he really liked. So Duncan was invited to bring his gear to our next little cafe gig, and from there, the volume cranked up and we basically morphed from an acoustic duo into the Torn Boys.

The Torn Boys were known for blending dreamy lyricism with synth rhythms and unique guitar textures. How did the individual members’ musical backgrounds and influences contribute to shaping the band’s sound?

Kelly: Jeff and I had our mutual influences and our history of collaboration, and Duncan Atkinson was actually an accomplished guitarist with a European hard rock bent, who brought his new interest in synth tones and the emerging electronic groups of the day. Speaking for myself, around that time XTC and Peter Gabriel and others were getting this strong acoustic guitar sound set against thundering drums, with compression, etc. So I was trying to place glittering chords against the churning guitar rhythms and the electronic sounds. Of course, the Big Book of Rock, 1969: ‘Velvet Underground Live’ was there for us to consult, and Jeff and I were experimenting with overlapping lyrics and near-rhyme singing.

Jeffrey: I was always attracted to language, the way a single word can emotionally charge a melody or a chord interval. I hadn’t written many songs at the time, and though it might be kind of vulgar to speak of these things out loud, along with the obvious singer/songwriter influences, I was also under the spell of certain writers: Michael McClure, Gerard Malanga, and some of the Surrealists. Also Paul Kantner… his songs like ‘Martha’ and ‘Crown of Creation’—a very underrated lyricist, in my opinion. My guitar playing was pretty primitive; lots of downstrokes on a cheap Fender Mustang, usually played through a Pig Nose amp, but it made sense with Kelly’s chiming acoustic chords. Kelly and I were already doing harmonies from our acoustic set, and then Duncan’s drum machine and synth bass gave everything a quirky, relentless drive.

For a few gigs in early 1983, a guy named Paul Ghidosi played ‘Trout Mask Replica’-style guitar with us. He’d been in CRLLL with Kelly and was kind of legendary around town for performing in a tattered clown costume or in drag as a housewife character he called “Gladys.” Paul was a lovely guy, and he loved the Torn Boys, but he had other fish to chase with his butterfly net, you might say, so that didn’t last.

We met Grant-Lee (Phillips) at an afterparty for a one-act play he’d directed. His friend Ian had heard Kelly and me spinning Torn Boys tracks a few nights before on the local college radio station. When Grant-Lee joined the Torn Boys, he played a hefty black Les Paul, and he’d somehow worked out a kind of Robert Fripp-by-way-of-Carl-Perkins hybrid sound. It sort of lifted the other elements onto a graceful sonic cloud. Grant was always the person we were supposed to play with; we just had to meet him.

“I feel like almost every Torn Boys song came about in a different way”

As one of the founding members of The Torn Boys, could you elaborate on the creative process behind crafting your original songs?

Kelly: Jeff would tend to have pieces of notebook paper with snatches of phrases and rhymes circling around. There’d be a riff or series of chords that we’d play with and attach to a structure. The melody would suggest a harmony line. Because the drum machine was relatively new to us, we were always open to something different. Duncan would show up with his latest drum pattern, and it was always exciting.

Jeffrey: I feel like almost every Torn Boys song came about in a different way. Usually, I’d meet up with Kelly first, with maybe a chord progression or a riff, sometimes just a song title, and he’d come up with musical approaches to brighten this element or cast a shadow on that one. With ‘See Through My Eyes,’ I brought in a very sparse, descending guitar line, and I had a melody and most of the lyrics, but if you listen to what Kelly does with his acoustic guitar underneath, he’s playing this strange and perfect counter-rhythm. He also adds those harmonies and vocal swoops. ‘New Drums’ started with that “angry hornet guitar” thing, just me attacking a few strings of my guitar, and Duncan laid down a drum pattern under that. It’s probably not even a song really, but more like a travelogue of a bad dream. ‘Fountain of Blood’ is a Baudelaire poem set to a krautrock rhythm. ‘Lady Luck’ wears velvet on its sleeves.

The release on Independent Project Records showcases a mix of rare studio recordings and live tracks. Can you walk us through the process of compiling and curating these materials after all these years?

Kelly: Well, first it should probably be said that during the era we were playing in the early eighties, the notion of there somehow being a Torn Boys “album” wasn’t even a pipe dream. No one did that—it just wasn’t a realistic option. The Torn Boys existed for only a brief time. During that year, year and a half, we recorded one session on an actual eight-track machine, a few on Duncan’s cassette four-track, plus a session recorded off the board of a live performance in a college radio studio. The few times we managed to record a song, it was because we wanted to hear it for ourselves or maybe to create a demo to get a gig. So, in a way, everything we did could be called “rare.”

Jeffrey: After 1984, we all went on to other phases of life and creative projects, but over the years Kelly would sometimes nudge me, like “…y’know, Jeff, that Torn Boys stuff we did back in the day is really good… hey, don’t forget about the Torn Boys.” So eventually, a decade or two into the 21st century, when Spotify and Bandcamp emerged, I dusted off my collection of cassette tapes, and Kelly and I sat down to listen to it all from the perspective of a potential collection, figure out which version of what song was the best, and so on. Leslie Medford was a major fan and happened to have a very complete collection of Torn Boys recordings, so his input was very useful in the project. Duncan dug up a few of his master tapes. To be honest, I’d forgotten some of the tracks we’d recorded. When I reconnected with Bruce Licher, I played this stuff dragged up from the eighties for him, and he thought it would be a cool thing to release through IPR.

‘May Day’ was released as a single along with a music video. What makes this song special?

Jeffrey: It’s a very early song of mine, written pretty quickly, as I recall, and the lyric is an example of my habit at the time of stealing directly from my dream journal. It’s a tension-and-release type structure, conveying a sense of longing and arrival. Do you know the song ‘She Moves Through the Fair’? ‘May Day’ is a primitive nod to that kind of feeling.

Kelly: Aside from the song being wonderful, we created an animated video for ‘May Day,’ based largely on drawings of mine, most of them culled from the era when we recorded the song. David Gresalfi directed the video, with some input from myself, Jeff, and also Ed Dahl, and we think it turned out really beautifully.

When did the band disband?

Kelly: Grant was always planning to leave Stockton for film school in Los Angeles sometime down the road, and Duncan was asked to join a synth-pop band that was going to play in Sacramento and that kind of thing. I was slated to play bass in a band in San Francisco. A friend, Leslie Medford, a Torn Boys fan, asked me to play in the Ophelias (later signed to Rough Trade US). I was set to move to the Oakland hills when my family’s business offered me a job that required me to remain in Stockton. The story of Jeff and Grant and Shiva Burlesque, and then Grant-Lee Buffalo, their solo work, etc., is for them to tell. And I do love that story!

Jeffrey: Grant-Lee had shared his plan to move to Los Angeles with his high school friend Ian. But that spring, right after we’d met those two, Ian died very tragically in an accident while on vacation with his family. It was such a sad and shocking thing. By July or so of ’83, the Torn Boys had pretty much played everywhere there was to play locally, and Duncan started doing gigs with some guys he knew in Lodi. Over the summer, Grant, Kelly, and I got to be friends and started collaborating a bit, and as September got closer, Grant asked me if I might also consider moving to Los Angeles to pursue music. Even though, as a native Northern Californian, I knew for certain I would never ever live in LA, I quickly decided I would do exactly that. Grant was a very special talent, a special person, and it seemed clear the Torn Boys couldn’t go back to what we were before he’d joined. It felt like the winds were shifting. I stayed on working in Stockton for a couple of months, saving some money, and during that interim, Kelly and I still performed locally in a pretty cool trio called the Bewlay Brothers. Then, right after Christmas of 1983, I drove my Chevy with all my stuff to LA, and Grant-Lee and I began sketching out a blueprint for what became Shiva Burlesque.

Could you share any memorable experiences from the early days of The Torn Boys, whether it be from recording sessions, live performances, or interactions with other musicians?

Kelly: We played with the band Game Theory in Davis, California. It was unfamiliar territory as we didn’t know anyone. Scott Miller, the leader of Game Theory, was fascinated with the guitar setup that Grant-Lee (Phillips) had. The whole time we played, he would stick his face into Grant’s Fender Reverb and then stare up at Grant. I barely noticed, but Grant was distracted and still talks about it!

Jeffrey: This show Kelly mentions was in the backyard of the infamous “Pirate Ship” house in Davis. That’s something you alternative music archivists out there might want to research. Grant tells me that the thing he remembers most about that gig was Scott Miller’s hair, which, to be fair, was amazing.

You were also involved in Gary Young’s Hospital after the dissolution of The Torn Boys. Tell us about it.

Kelly: I arranged the first recording date for Pavement, in addition to setting up Scott (Kannberg) and Steve (Malkmus) with Gary. That enterprise exploded across the world and eventually looped into Gary’s personality. He ended up leaving Pavement, recording back in Stockton at his home studio, and forming Hospital, which I joined along with my friend Zac Silver, who played guitar and sang backup vocals. We toured with Mercury Rev, Dirty Three, Pavement, Sonic Youth, Blonde Redhead, etc.; played Lollapalooza in 1995; and released two albums: ‘Hospital for the Chemically Insane’ and ‘Things We Do For You.’ After Hospital disbanded, I did one more big session with Gary on drums for a project called ‘Blue Boy Cometh.’ That was the last thing Gary did. I hope people get to hear it, ’cause he was on triple fire.

What else occupied your life?

Kelly: I worked for twenty years in Forensic Psychology, starting in recreational therapy through the University of the Pacific and eventually assisting in diagnostic evaluations for the criminally insane. They would be transitioning from prison to their county, and we’d house and evaluate their physical, emotional, and mental states. I retired in 2012.

Jeffrey: Post-Torn Boys, Grant-Lee and I formed Shiva Burlesque, and we released two albums, the second of which, ‘Mercury Blues,’ was recently reissued by IPR.

I also recorded a couple of solo albums, ‘Sheer Golden Hooks’ and if/is, which I’m equally proud of.

In the late ’90s, I moved from Los Angeles to Nevada City, California, and around the turn of the century, I bought and renovated a little arthouse cinema (where, by the way, Joanna Newsom played her first solo show), and out of which grew the Nevada City Film Festival, for which I served as a director. Recently, I co-produced a documentary film called Louder Than You Think about Gary Young, the original drummer of Pavement (in which Kelly plays a key role, by the way). And most importantly, I’ve been a father to my son, experienced my share of challenges and incredible life adventures, met some remarkable people, and made lasting friends.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favorite albums. Have you found something new lately that you would like to recommend to our readers?

Jeffrey: There’s so much music flowing out all the time now, all over the world, but everything is atomized into sub-genres and sub-sub-genres… I’m sure your readers could educate me. None of this is brand new, but the Black Angels out of Austin make a mighty, psychedelic roar. Mica Levi is brilliant. Tim Hecker recently released some incredible new material. Angel Olsen. Dry Cleaning made some exciting music in the past couple of years. That André 3000 flute album is a trip. One of our IPR label-mates, Alison Clancy, is someone to check out. And John Cale just released an album. Does that count as new?

Kelly: ‘Taking Tiger Mountain By Strategy’ (Brian Eno); ‘Music Has the Right to Children’ (Boards of Canada); ‘You’ (Gong); ‘A Wizard, A True Star’ (Todd Rundgren); ‘The Bells’ (Lou Reed); ‘Hissing of Summer Lawns’ (Joni Mitchell); ‘Exorcising Ghosts’ (Japan); ‘The Dreaming’ (Kate Bush); ‘English Settlement’ (XTC); ‘Blood on the Tracks’ (Bob Dylan); ‘Quadrophenia’ (The Who); ‘Lizard’ (King Crimson); ‘Spirit of Eden’ (Talk Talk).

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Kelly: As Jeff wrote in one of our Torn Boys songs: “…the tattoo of what’s yet to come, the beating of new drums.”

Klemen Breznikar

Independent Project Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube