His Name Is Alive | Interview | New 6xLP Boxset

Warren Defever’s iconic project, His Name Is Alive, receives the royal treatment with ‘How Ghosts Affect Relationships: 1990-1993,’ a lavish 6xLP box set that resurrects the band’s haunting early albums for a new generation of listeners, thanks to 4AD.

This limited-edition box set is more than a nostalgic trip; it’s a deep dive into the shadowy, dreamy corners of ‘Livonia,’ ‘Home Is In Your Head,’ and ‘Mouth By Mouth,’ newly remastered by Defever himself at Third Man Mastering.

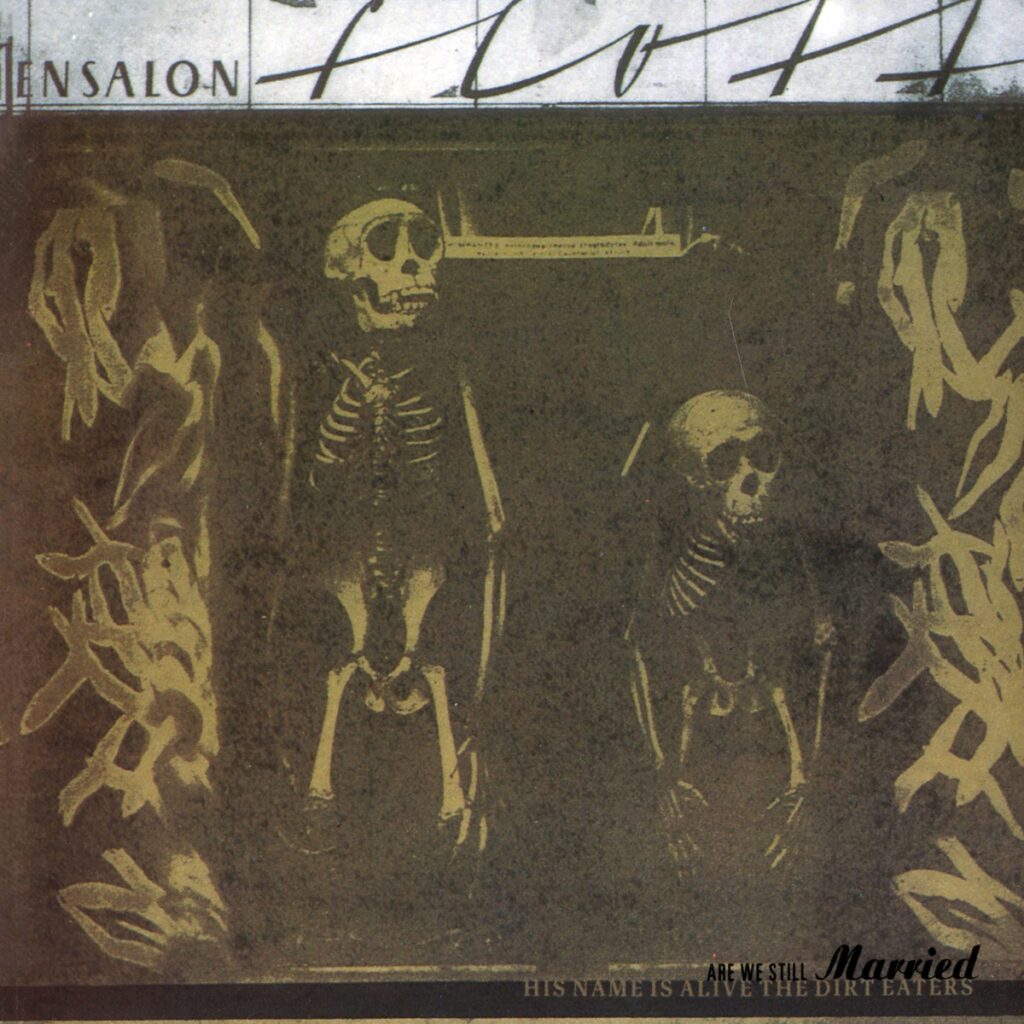

Fans will find more than just the classics in this release—the box set includes three extra LPs of rare and unreleased material, featuring hidden gems from ‘The Dirt Eaters’ EP that never made it to the stage. With Defever’s meticulous remastering process, listeners can expect a preservation of the original spirit of these tracks.

From the deep intimacy of home-recorded ambient guitar solos to live performances that capture the energy of the band’s early days, ‘How Ghosts Affect Relationships’ preserves the original versions on streaming platforms. This allows fans to explore both the untouched magic of the original recordings and the enhanced clarity of the remasters.

With a limited number of these box sets available, ‘How Ghosts Affect Relationships’ promises to be a treasure for both old and new fans, preserving the delicate, otherworldly sound that captivated listeners three decades ago.

“I was a curious child exploring all the options”

When you first recorded ‘Livonia,’ did you have any sense that you were crafting something timeless, or were you more focused on capturing the spirit of the moment? How does it feel to revisit those early recordings with the benefit of hindsight?

Warren Defever: I was a kid. I hadn’t met anyone who wrote songs. Although I started performing when I was five, there was never any discussion about the creation of songs; I had no idea where they came from. It was a secretive process shrouded in mystery. To this day, I still haven’t figured it out. I recorded almost entirely alone and unsupervised for years. Timelessness or capturing the spirit of the moment were not considered, although my process was pretty much just recording myself improvising. The songs on ‘Livonia’ are usually not only the first take but the first time I ever played the song. It would have been unimaginable to fathom back then that anybody would still be listening to those recordings thirty years later or that new generations of listeners would ever find that music. Honestly, at the time of the recording, it was unfathomable to me that they would ever get released or that anyone would ever hear them. They were private. I liked timelessness as a concept, but I recognized that my musical education—playing country, western, polkas, and waltzes with my grandfather—did not relate much to what was going on in the world, except for the old people. And believe me, when they heard the opening strains of ‘The Beer Barrel Polka’ or ‘Roll Out the Barrel,’ they could not resist the desire to get up out of those chairs and do the half step, which is similar to a waltz but faster since it has one less beat (waltzes are in three-quarters time, and a polka is in 2/4). Going back to those tapes has been a very unusual experience because there have been enough decades in between for me to only remember vague feelings about the music and not the specifics of the moment. Keep in mind, I lived with my parents at the time of the first three albums—’Livonia,’ ‘Home Is In Your Head,’ and ‘Mouth By Mouth’—so my recordings were often interrupted by my mom doing the laundry or picking out what shirt I should wear to school or for a photo shoot. My dad would only occasionally interrupt when I woke him up from playing too loud, and then he would refer to it as noise. I was just a kid.

4AD’s aesthetic is often described as ethereal and otherworldly, yet your work has always stood out as being even more fragmented and enigmatic. What was it like to have your sound molded and reshaped by Ivo Watts-Russell and John Fryer? Did you ever feel like they were seeing something in your music that even you hadn’t recognized yet?

When I started sending tapes to Ivo, it hadn’t occurred to me that our songs were shorter than normal songs, or that they didn’t have a chorus, or that the verse only had four or six lines. Only after we agreed to make it into an album, and I was typing up the lyrics, did I realize they didn’t take up very much space on the page compared to a normal album and that he was using elements of each song multiple times over the course of the record so that it would reach a 30-minute minimum requirement for it to be legally considered an album. I didn’t consider them fragments because each piece made up an important part of the whole picture. It was a different way of looking at or grouping time. Two or three songs might take up the space a normal song would take up, but they flowed together like separated movements of a ballet, or similar to when your crazy neighbor—who you’re pretty sure has a serious drug problem—stays up for two or three days at a time and then sleeps for four days straight. It’s fine; everyone can do their own thing. We weren’t necessarily doing it on purpose, but it worked out. At the time, I really didn’t have the proper technology to make a finished mix that could be made into an album. It was cassette-to-cassette technology, so Ivo and John Fryer were able to create not only amazing mixes, but also, someone had to—and it wasn’t gonna be in my basement. I cried when I heard the finished album; it was sort of like what I was doing except now it was really good. I’m so glad that happened. I had been sending Ivo non-stop variations of mixes, and he made a thing that was literally all the best parts combined, isolated, flipped, or stretched out. I don’t think they realized how depressingly limited my home setup was, so they were able to unhesitatingly weave their alchemical web at Blackwing Studio in London. Gold, pure gold. It wasn’t gold when I was doing it; it was rough and broken, and then they poured liquid gold all over it and made it beautiful. They put in “more love hours than can ever be repaid,” as the old saying goes, and so I am forever in their debt.

You’ve always seemed to approach recording as an experimental process, almost like a form of alchemy. Can you walk us through how that philosophy evolved between ‘Livonia’ and ‘Mouth By Mouth’? Did your understanding of your own creative process change significantly during that period?

It’s not a well-thought-out experiment, and there’s no standard procedures, hypothesis, or planned demonstration or determination. In the early times, recording and writing were a combined, simultaneous process, so whatever felt good or sounded good was kept, and the rest was discarded. Also, I didn’t seem to learn anything about what worked and what didn’t. It was very random. I was a curious child exploring all the options, pushing all the buttons at the same time, and going on many adventures. By the time we did ‘Mouth By Mouth,’ we had an accountant, a booking agent, a mailing list, and an American distribution deal with Warner Brothers Records. It was a very different time. When I first started, they didn’t even make sunglasses for kids yet—children would just walk around in the summer staring directly at the sun with no UV protection, or worse, they would wear the comically large sunglasses intended for their parents. By the time we were working on ‘Mouth By Mouth,’ Lollapalooza was a thing, and Siouxsie and The Banshees were sharing a stage with Ice T. In those three years, the world had aged a lot. My creative process in that time grew exponentially. I now had two drum sets, a couple of drum machines, and a sampler. ‘Mouth By Mouth’ has like five different singers on it. It was crazy.

‘Home Is In Your Head’ is like a sonic scrapbook, with moments of serenity juxtaposed against bursts of noise and chaos. Was this reflective of your life at the time, or were you deliberately trying to create a listening experience that felt unstable and unpredictable?

It’s hard for me to judge how much the music reflects my own life, but songs with ‘Schizophrenia’ or ‘Mescaline’ in the title often point listeners in a certain direction.

‘The Dirt Eaters’ EP leans heavily into folk while still embracing your avant-pop roots. It also features some pretty audacious sampling choices. What drew you to the dialogue from Hollywood films, and how did it inform the EP’s overall tone and atmosphere?

Sampling was still uncharted territory at the time, and it was unclear what our reach was going to be, so I didn’t hesitate to take quotes from Jack Nicholson or create entire songs out of Prince samples. In the back of my mind, I’m still waiting for a phone call from their lawyer. The words are always important to me, so whether the source is William Butler Yeats (‘I Dreamed That One Had Died’) or Stevie Wonder (‘When You Dream of Things You Can’t Understand’), I will take them and combine them or mix it up a little. There’s a line somewhere between copying, stealing, and a loving tribute—that line becomes more unclear as I get older. More contributors meant each individual person contributed less, but there was an increase in what I call the “everything vibe” where nothing was off limits, there were no guardrails, and I didn’t know where to stop. I wanted to include everything and everyone. I had a lot of energy.

How much did Livonia, Michigan influence the sound and mood of these early albums? Do you think the environment you grew up in left an indelible mark on your music?

Livonia as a city is a cultural void. It exists only in between other places. It’s not quite a negative, but it’s definitely not a positive. John Sinclair, MC5 manager, White Panthers, etc., famously said, “I’d rather go back to jail than go to Livonia.” It’s six by six square miles; all the streets are neatly laid out in a grid. It has no diagonal streets. The streets have names like Five Mile Road, Six Mile Road, and Seven Mile Road. It’s the exact inverse of Detroit. The city of Livonia does not contain a downtown; the city hall is flanked only by a library, a dry cleaners, and Bates Hamburgers, which is not even open 24 hours. It’s like driving by a place where there used to be something important and pointing out the spot to the other person in the car, except there was never anything there to begin with. Bored teenagers have nothing to do there except break into their neighbors’ houses when they are on vacation in Florida and steal their TVs. I avoided a life of petty crime by turning inward, putting on headphones, and recording everything through an echo pedal.

When you set out to remaster these albums at Third Man Mastering, what was your approach? Were you aiming to preserve the original spirit of the recordings, or did you find yourself wanting to tweak or enhance certain elements now that you had more advanced tools at your disposal?

For about six years now, I’ve had the tremendous luck and pleasure to work in a mastering studio in Detroit that is owned and designed by Jack White. It’s outfitted with incredible rare vintage tube and transformer-based gear, as well as all the latest modern digital contraptions. Everyone over there is weirdly nice to me, and I try very hard not to ruin it. My previous job experience was working in a cornfield in the summers in Canada. What I’ve found over the years is that each project has its own unique set of circumstances, and each record is really different. There is not one approach or process that works for everything. It’s important to understand the goals or intentions of each artist or producer and help them sonically complete their mission. I’ve worked on a wide variety of albums over the last few years, and a lot of the knowledge that I’ve accumulated was really tested when working on my own recordings from thirty years ago. There are tools now that really didn’t exist back then, but we’re not talking about “do weird things” tools—more like “zoom in on that one thing that was previously impervious to zooming.” One of the nice things about working with 4AD on this is that they keep the old versions available on streaming, so it’s not an either/or choice—you can have both, you can have it all. I approached these records with the idea that there weren’t any major problems that needed correcting, and a complete overhaul or makeover was not required. I mostly cleaned up minor things, reduced but not totally removed weird random clicks and pops or tape hiss that became a distraction and pulled the listener’s attention out of the music. British specs have always been slightly different than the US, so I did lean a little more American in a few areas, but nothing more than a dB here and there. My tweaks are subtle, nuanced, and in keeping with the original spirit. I really hope everyone enjoys going back to these albums; after not listening to them myself for decades, they are quite special.

Your work has often been described as a “sonic jigsaw puzzle.” Do you view your music in that way—as pieces that may or may not fit together, forming a bigger, sometimes ambiguous picture? How do you approach sequencing an album to maintain that fragmented yet cohesive feel?

I’m not looking to start anything here, but I would like to think that the pieces all fit together pretty well, and maybe it’s just not obvious the first time—give it one more go. Sometimes you didn’t like kimchi the first time you tried it, but then it kinda grew on you. Or like when you snuck into your parents’ liquor cabinet and drank all the tequila—that was probably an unpleasant experience, but now that you’re a little older, it’s fine, it’s like really, really nice special water.

As far as sequencing goes, I do have some thoughts on that—don’t worry too much conceptually about the sequence. Listeners will decide for themselves which songs mean what to them; you can’t second-guess the listeners. What you can do is figure out which ending flows nicely into the next song’s beginning, and as long as that goes well, everyone will fall asleep and it’ll be great. Don’t do the jarring transitions and no sneak attacks. Put on the album really quietly with the speaker next to your bed, and get it so it’s just around the same level as sounds from the street, and see if anything jumps out.

With the short tour planned in celebration of this box set, how do you approach performing these early songs live now compared to when they were first written and recorded? Has your relationship with the material changed over the years?

I still play all the old songs all the time myself on guitar, bass, or piano. They’re not hard to play, and they mean a lot to me. I’ll never not play them. Once you add the audience, the rest of the band, a contract with a promoter, and then the audience is staring at you the whole time, not saying anything—that can get a little distracting. So the challenge is how to stay focused on the part that’s important to you and not turn it into Project Merch Table.

The bonus LPs in this box set include rare and unreleased tracks. Can you give us a glimpse into what listeners can expect from these tracks? Are there any particular songs that you’re especially excited for people to hear?

A few years ago, we released a series of albums of early home recordings that pre-date the ‘Livonia’ album on the Disciples label: ‘All The Mirrors In The House,’ ‘Return To Never,’ and ‘Hope Is A Candle.’ Some of the bonus tracks on the new box set reveal that I never really stopped doing low-key ambient-ish guitar solos at home when no one was around. I’m glad for the opportunity to sort of put that in context. Also, there are some live tracks from around ‘Livonia’ and ‘Home Is In Your Head’ where we play the songs just as they were recorded, and it’s weird how accurate they are. We didn’t really tour much back then—just a few shows around Detroit, New York City, and Chicago. There are also some bonus tracks from around the time of ‘Mouth By Mouth’ of our other band called The Dirt Eaters that were only available on a cassette demo, and I think people will freak out when they hear those.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately you would like to recommend to our readers?

Embarrassingly, lately I’ve been working on a mixtape called John Lemmon, which is mostly made up of John Lennon songs from the Beatles, like ‘Baby, You’re A Rich Man’ and solo tracks, and a couple of Nilsson songs. More importantly, here’s a couple of new bands (and one old band) I randomly found on Bandcamp that I strongly recommend to the people:

Cryogeyser (LA), Gimu (Brazil), Warrington-Runcorn New Town Development Plan (UK), Un Programme (Sweden), Brenoritvrezorkre (France), t — e — u — (UK), Diamond Day (Canada), Sophiyah E (Detroit)…

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thank you, xoxo war

Klemen Breznikar

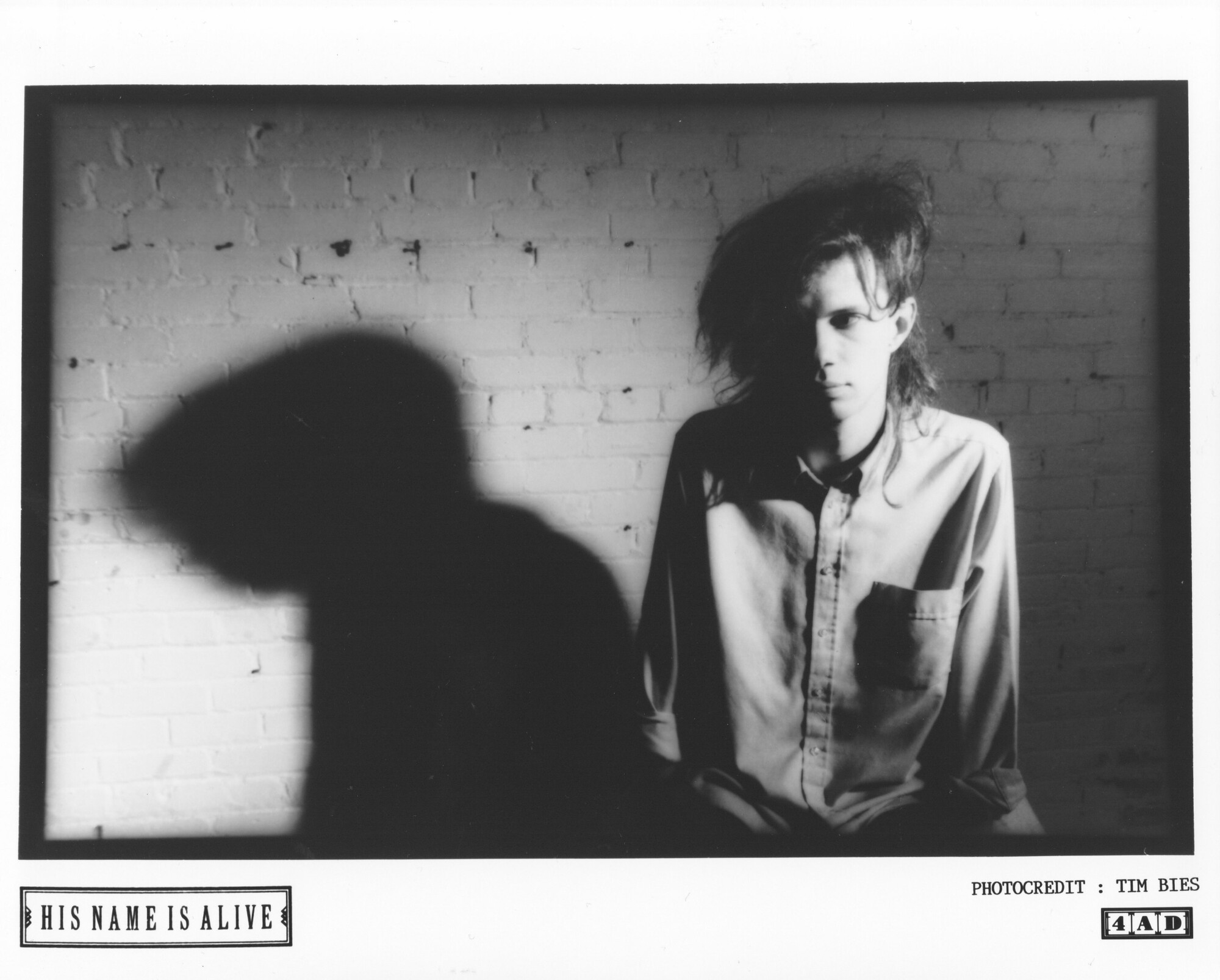

Headline photo: Tim Bies

His Name Is Alive Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp

4AD Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube