Morgan Fisher | Interview | Beyond the Keys: Journeying from Mott the Hoople to British Lions and Beyond

Morgan Fisher is a true keyboard wizard with a wild spirit that’s been bubbling over for more than 55 years.

As a very accomplished English keyboardist and composer, he might be best known for his time with Mott the Hoople in the early ’70s. He began his musical journey with the group Love Affair, achieving success with the classic hit ‘Everlasting Love’ before forming the progressive rock band Morgan, joining Mott the Hoople and beginning with British Lions. Later on Fisher moved to Japan, where he has been exploring ambient music and visual artistry. In recent years, he has developed a captivating form of Light Art that reflects his creative vision, all while remaining an active figure in the music scene.

Now working from his studio in Tokyo, he likes to collaborate with different artists around the globe. With influences like Keith Emerson and Ray Charles flowing through him, he always like to experiment. Now, he’s digging into the vaults to remix and revive his past performances, while also gearing up for an epic 50th-anniversary DVD of ‘Mott in America.’

“Melodies come from nowhere, but you have to know how to invite them”

Are you excited about the recent British Lions 2-CD expanded reissue out via Think Like A Key Music of your hard rock album from 1978? Listening to those tracks today, what are some memories that run through your mind?

Morgan Fisher: Yes, of course, I am because that’s a band I thought never got as far as we should have, for various reasons. One was management not being quite as clever as they should have been, and two was that we came out around the same time as punk rock.

In England especially, the media was focused on punk rock and implied that musicians like us—who were actually only about five years older than the punks—were kind of old-fashioned. This is what the media does all the time. They want something new; they want the future of rock, and anything old is quickly ignored.

So we were overlooked in England. We thought we could have done better in America, where punk rock wasn’t as overwhelming, and classic rock was still appreciated. But we didn’t get enough promotion there, so it just didn’t work out as it should have.

I think the songs are excellent. There’s not a song I don’t like. And, of course, we had an amazing singer and songwriter in John Fiddler. The whole experience was musically enjoyable, and the concerts were great—nearly always.

They were really well received, but just not by enough people. If there’s one thing I feel when I listen back to the songs, it’s a certain tension. Partly from John, as he—and we—were kind of desperate to make it. That can be a good thing, but sometimes it adds too much tension or even aggression to some of the songs. When you listen to John Fiddler’s songs before and after British Lions—in Medicine Head—they’re much more relaxed, warming, even healing, like what he’s doing now. So in a way, we all tried really hard then, but maybe lost some of the feeling in the music because we were trying too hard.

But I don’t regret any of it, and I still enjoy the music. I’m very grateful there’s a chance for others to listen to it now.

How did you originally meet other members of British Lions, and what do you think was the overall vision for the band?

Well, after Mott the Hoople, we got a new singer and guitarist, Nigel Benjamin and Ray Major, and made two albums that also didn’t go as well as we’d hoped. We decided to continue as a band without the singer, who didn’t quite fit what we were doing.

I already knew John Fiddler and was a big fan of Medicine Head. In fact, during Mott’s winding down, I had some time off, and John asked me to join the last tour of Medicine Head, which he was also wrapping up but had already scheduled across Britain. So I played with him for that.

I got to play with John for maybe a dozen shows and really enjoyed it. Once Mott decided to look for a new singer, it just seemed obvious. John was winding down Medicine Head, and Mott was losing our original singer and looking for someone new. So I proposed the idea to John, and he said he’d think about it. The rest of the guys in Mott were very excited about it.

I remember going to John’s house, where he was supposed to give me his decision. All the guys in the band were eagerly waiting for the news. When John said he wanted to do it, I called the others, and everyone was thrilled. John came up with new songs incredibly quickly and took over from Overend Watts as the main songwriter, since Overend had written many songs for Mott after Ian left.

John wanted to sing his own songs, and I understood that, so he quickly became the main songwriter, and musically, it took off very smoothly.

Did you do a lot of shows? What are some of the most memorable with British Lions?

So I looked at the list, and there were about 110 shows, though we scheduled over 140 with a lot of cancellations for various reasons. Anyway, the first thing we did was a tour with Status Quo, since we had the same manager. He thought it would be good for us to open for Status Quo on their tour, and it went very well as we had similar rock styles.

Then we went on another English tour with AC/DC, who were still fairly new but already successful, and they had Bon Scott as their original singer. That tour also went well. After that, we did a long tour in America with Blue Öyster Cult, a slightly different kind of band, but it gave us good exposure.

In between, we did plenty of our own concerts, mainly in England, and we became a very tight live band. I don’t remember any specific standout concerts, but one of the last we did was at the Old Waldorf Club in San Francisco, where we played two nights. That was a lot of fun—pretty wild. The singer from Blue Öyster Cult even came to see us, which was nice.

After that, we only had two more shows before the band ended. We did two concerts in Los Angeles at a rather depressing little club, which I didn’t enjoy much. By that point, the band was over. I think RSO Records in America decided not to release our second album, and the English label made the same choice. We had a second album that we liked, but they didn’t want to release it, so that was sadly the end of the story.

How did you first get interested in the keyboard, and how would you describe the music scene in the early ’60s?

Well, actually, I think I was about six when I first touched a piano at my grandma’s house. It was very old and out of tune, but it felt magical just reaching up and banging on the keys. I couldn’t play yet, but I was fascinated by the sound. After that, when I was about seven or eight, my parents had a guitar. I don’t know why they bought it; nobody else played it. It was a very cheap old acoustic guitar, but I managed to pick it up and make a few phrases on it. I enjoyed that, but I didn’t go very far with it. It was more of a bit of fun than a passion. But then, luckily, my mother bought a piano—she was a bit of an amateur classical pianist—and we got a nice, tuned piano at home. So, I started playing a lot, from about the age of eight, mostly light classical music and similar things. I began reading a little bit on my own. At ten, I told my mom I wanted piano lessons, so we found a teacher nearby, an older lady but a nice teacher. I had just a half-hour lesson once a week, but it was enough to inspire me. I learned to read music, play scales, and train my ear, which was very important later in life.

Around that time, I asked my teacher if there were any other pieces I could play, as I was getting a bit bored with some light Bach pieces written for his daughter. They were nice, but I thought the melodies were a bit trite. She introduced me to a course of study written by composer Béla Bartók. His pieces were amazing and unlike traditional Western music. They weren’t just in major or minor keys but used strange harmonies and rhythms like 5/4 and 7/4. This fascinated me. By twelve, I was already on a sort of path toward progressive rock. I started listening to modern classical composers like Stravinsky, Debussy, and my favorite, Satie. I never aspired to be a classical pianist or anything. I didn’t want to take it that far, and I wasn’t very good at practicing all the time as classical musicians need to.

So, naturally, I started listening to pop music. My first rock and roll record was when I was seven—it was by an English singer called Adam Faith, who I saw on television and was fascinated by. Then, at thirteen, the Beatles came along, and I was the right age to be entranced by them. I liked the first two singles, but it was their third single, She Loves You, that really hit me hard. It came storming out of my radio, and I was blown away. I thought, This is what I want to do musically. So, I stopped piano lessons, listened to pop music on the radio, and got weekend jobs to earn money to buy records. I trained myself by ear, putting the record player on top of the piano and listening, playing, and learning until I got the songs. This was excellent training, and I recommend it for any young student. I did this for four or five hours a day, and I’m amazed my parents didn’t tell me to shut up!

By fifteen, I was getting interested in girls, fashion, and the mod lifestyle, as opposed to being a rocker. My parents were teachers, so I naturally leaned toward the more stylish, middle-class mod fashion. Mods were all about soul music, which I adored, especially Tamla Motown and Stax Records. I bought lots of soul records and learned many classic songs from artists like Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and James Brown. At sixteen, a nearby friend mentioned he was joining a new band and asked if I’d like to join. That friend was Steve Ellis, a very good soul singer. I think he was only fifteen at the time, and we joined this band that was being put together by a drummer’s father. It was called The Soul Survivors.

At sixteen, when you began playing organ for The Soul Survivors, what was your repertoire?

Yes, it was mostly soul covers—Stax Records and Tamla Motown, with maybe a bit of blues and Van Morrison. Pretty traditional stuff for those days, but cool nonetheless. At that time, I started watching Jimi Hendrix, who was playing in London pubs before he even got a record out. He just blew my mind, though I never thought I could play like that; I was just amazed by him. But our band stuck to a basic soul repertoire, which was easy to learn but required the right feel, and we had a strong singer. We were a five-piece band, and they bought me my first organ, a Vox Continental, the same type used by The Animals and also by The Doors. It was a classic, stylish design, with the keys in reverse colors and a bright red body. I was thrilled to have it.

Did you make any recordings with The Soul Survivors?

Yes, we made one record in 1967 when I was seventeen. We got a deal with Decca Records. Through Decca’s A&R, we were asked to record a Rolling Stones song, ‘She Smiled Sweetly.’ We didn’t choose it—they did. It was a nice song, though not hit material, but we did as we were told and recorded it in the same studio the Stones used for their first album, Regent Sound on Tin Pan Alley in London. That was exciting, even though the studio was basic. The single sold nearly nothing, but we were out there in the public marketplace.

What led to the name change?

We had to change our name because there was already a band in America called The Soul Survivors, known for their big hit, ‘Expressway to Your Heart,’ which was also popular in England. They heard about us and told us we couldn’t use the name. Since they were bigger than us, we agreed to change it. I can’t remember who came up with it, but I remember the name came from a romantic TV series on BBC called The Love Affair, and we all thought it sounded simple and memorable. So, we became The Love Affair.

You took a short break to finish your final year at Hendon County Grammar School.

So, yeah. We had just released that one single, and then I decided I wanted to become a professional musician and leave school. I was 17 and already had a pretty good education. The problem was, my parents were both teachers. When I asked them if I could leave school to become a full-time musician, they said, “No, you really should finish the last nine months to complete high school and get your final exams, so you’ll have the option to go to university.”

Reluctantly, I agreed, told the band I had to leave to finish high school. They were sad but supportive. It’s one of my regrets, not standing up for myself, because while I was away, the band’s next record, ‘Everlasting Love,’ became a number one hit. To say I was gutted isn’t an exaggeration.

So there I was, just wondering what to do. There had never been an agreement for me to rejoin the band after high school, but nine months later, I wrote them a letter to say I was done with school and available. And here’s the miracle—they wrote back and said, “Well, actually, Morgan, we’re not really getting along with the guy we replaced you with, so why don’t you come back and join the band again?” Within a week, I was in rock-star clothes and appearing on TV. It happened that quickly.

By that time, the band had two hits—’Everlasting Love’ and ‘Rainbow Valley’—and we were up and running, touring everywhere. I think one of the first tours we did was in the UK with Scott Walker, who headlined. We were second on the bill, along with other acts, including the amazing Terry Reid, who stood out to me every night. It was an incredible time.

Could you share some memories of recording your debut album with Love Affair? How do you remember the songs and studio time?

Having a number-one hit opened a lot of doors. We were on TV constantly, touring Europe, doing German TV shows, and giving interviews. It was exciting for a young kid. We were starting to write some of our own songs while keeping a bit of the soul style, so when I rejoined, they were halfway through making the album, which was thrilling for me since I loved being in the studio.

This time, it was a better studio—CBS Columbia Studios in London. It was 8-track, which was amazing then. I started overdubbing keyboards, using everything available—Mellotron, harpsichord, vibraphone. On the road, I just had a Hammond organ. We’d upgraded from a Vox Continental to a proper Hammond, which sounded incredible. Studio time was a lot of fun, and we quickly finished the album, ‘Everlasting Love Affair,’ which sold reasonably well.

Our singles, though, were mostly picked by the record company. They’d find soul-pop songs that fit our style, and only Steve Ellis, our singer, actually performed on the singles—the rest was done by session musicians. It was a common practice at the time. Even bands like The Kinks had session musicians like Jimmy Page. It was a trade-off because the record company controlled more back then, unlike indie bands today. But on the albums, we could play our own music and be more original, which was satisfying.

What was it like to get back and record ‘New Day’?

The second album, ‘New Day’, came a bit later, after four or five singles. We were listening to progressive rock—Hendrix, Cream, Spooky Tooth, Pink Floyd—and wanted to move in that direction. The singles were selling less, so we thought, “Why not go progressive rock?” We even changed our name from Love Affair to LA, aiming for a new identity. But it was a mistake. Progressive fans weren’t interested in a former pop band, and the pop fans didn’t care for progressive rock. It basically ended the band.

By that time, Steve Ellis had left for a solo career, and we got a new singer, but it wasn’t the same. So we decided to call it quits. I thought, “If I can’t go into progressive rock with Love Affair, I’ll do it with my own band.” Our manager agreed, and we formed Morgan, with Maurice Bacon on drums, since he loved progressive rock too. We found a bassist, Bob Sapsed, and auditioned singers until we met Tim Staffell, who was great.

Morgan was my chance to create a more keyboard-focused band. I was inspired by The Nice and Keith Emerson and wanted a band with no guitar, just keyboards, bass, and drums, plus a singer. We signed with RCA in Italy since the UK market was flooded with progressive bands. Italy was big on progressive rock, and recording there was perfect—the RCA studio had some of the best equipment, including rare keyboards used for film scores. We made the most of it and recorded our album, which sounded great, but it didn’t sell much. They gave us a chance to make a second album, but it was never released. By then, I decided to stop the band. We did play quite a few concerts, though.

Tell us about your project. Did you do a lot of shows at Morgan?

Well, quite a lot, yeah. We did about 20 shows at the famous Marquee Club in London. The manager liked us and gave us a residency there where we played every week for a while.

That was really good practice. I mean, it’s a great club, and you get a good audience coming in. Tim Staffell came to my Morgan band after he left Smile, a band which had Brian May on guitar (and Roger Taylor on drums). Brian May used to come often.

I’d see his tall figure standing in the audience, and I think he picked up some ideas for Queen from those gigs. In fact, Love Affair had already played the Marquee about 20 times, so we had a very good relationship with that club.

Of course, it’s a classic venue now, where nearly all the major bands started or started to gain fame. I began going there when I was 16; I even saw David Bowie there when he was just 19. So, the Marquee Club was a big influence. We played all around the country, and occasionally abroad—though not often. We were a hardworking band, but eventually, we all felt down about the record company not releasing the second album.

At that point, I thought, “I don’t know what we can do from here.” Musically, I’d done my best. I was satisfied with that; I’d done some really interesting pieces and worked hard. It was tiring, really, since I was a lead player and composed nearly all the music. I could use a break, so this would be early 1973. By 23, I was already feeling a bit jaded. I’d had five very hardworking years in the music business with some success, and I started to wonder, “Is this the end of my career?”

So, I got a day job driving a delivery van for what we call an “off-license”—a liquor store. I delivered alcohol around my area. It was a simple job, and the customers were always happy to see me. But while I was doing that, I kept an eye on the back pages of Melody Maker for other bands, just in case something came up that I’d want to join. I didn’t really have the energy to make another new band of my own—I needed a break—but I wanted to play something. And then, interestingly, I saw a listing for the Third Ear Band, who were very underground at the time. They’d never had a keyboard player before—they actually wanted a synthesizer player, which was something I was into doing.

So, I played drones and strange noises for them. They’d recently done the soundtrack for Macbeth by Polanski, so they were popular in the underground at least. But something came along very quickly after that, so I only did a couple of shows and radio shows with them.

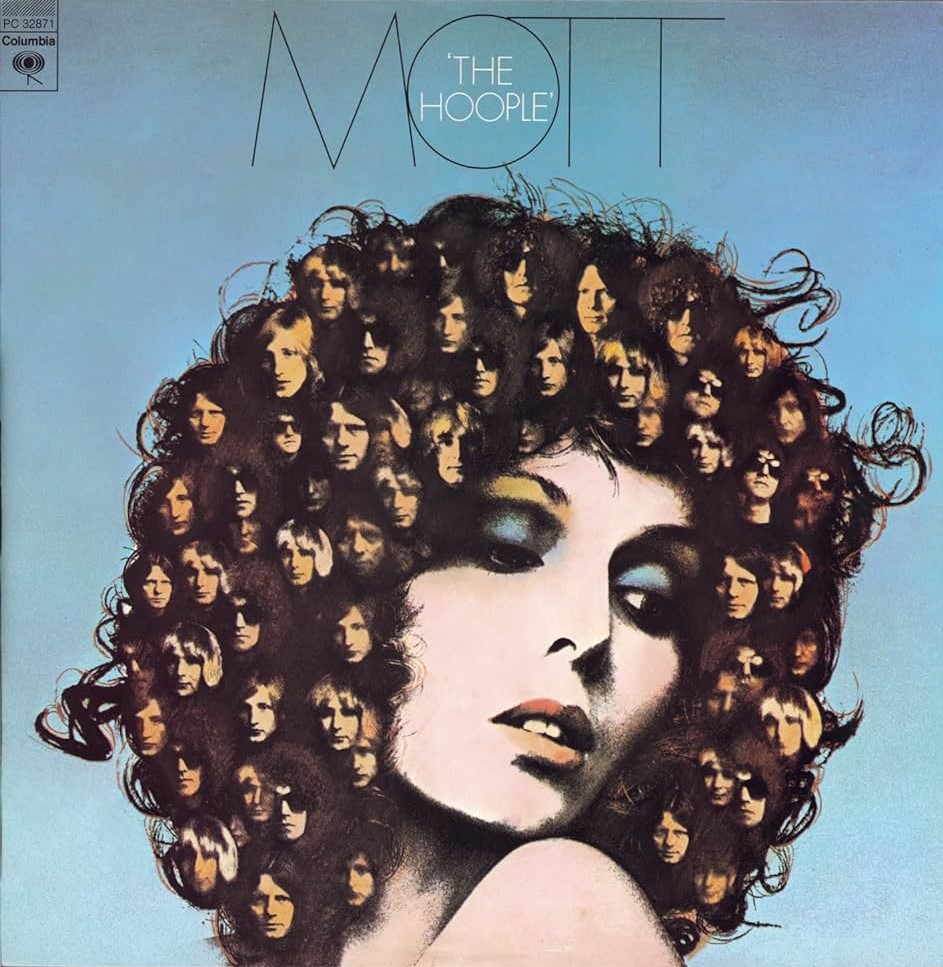

So what led you to join Mott the Hoople?

Suddenly, I saw another ad in Melody Maker: “British big name band needs keyboard player for upcoming American tour.” They never said who they were in these ads if they were famous, because it would attract too many fans and hangers-on to the audition. I called them up, they said to come down, and it turned out to be Mott the Hoople. I passed the audition and got the job, mostly because I was intrigued about going to America. I’d been all over Europe, but never America, and I really wanted to go there.

So, I joined them. I wasn’t really a Mott the Hoople fan; I think I’d seen them once, but I was heavily into progressive rock at the time. I thought of them as a good basic rock band, but I never bought any of their records. However, I really liked them as people. At the audition, we hit it off right away. In fact, the guitarist, Mick Ralphs, invited me to share a flat with him. That was a good way to join the band and get to know them. They were great players, and the more I played with them, the more I realized how good they were—not in a progressive rock way, but in a soulful way. The lyrics were heartfelt, Ian Hunter was a great songwriter, and the rhythms and riffs were solid. I’d say it was the best rhythm section I ever played with. The bassist and drummer were powerful and tight, and I really enjoyed playing with them.

It was an amazing experience, though in the end it was only a couple of years out of my life. It shines like a beacon in the panorama of my long career—an unforgettable experience, a real peak. It was incredible to see and learn about America, traveling with a successful band. They’d already had All the Young Dudes, so we’d play for 5,000 to 10,000 people most nights, with amazing opening bands. My first gig with them was in Chicago, with Joe Walsh and Barnstorm as the opening act. Joe Walsh was at his peak, and he totally blew me away. He did several other gigs with us, and I became a huge fan of his.

The second night was completely different but equally amazing; the opening band was the New York Dolls. This was 1973, three years before punk, and they were already doing punk rock. They were passionate, wild, and looked incredible. We did 11 shows with them, and I watched them every single night. From there on, we toured with fascinating bands, some big names, and it was a wild and wonderful time. Sometimes we’d do three-month tours all over America, which was incredibly hard work, but we were young and successful. We enjoyed all the things rock stars do at that level. Oddly enough, there were very few drugs in the band. I never got into drugs myself, though I did get seriously into drinking. It never affected my playing—just left me with continuous hangovers. And, of course, there were lots of girls, which was fantastic for a British boy. American girls were a lot of fun, I have to say.

Then there was the music. I did one album with them called ‘The Hoople,’ which we recorded at Air Studios, George Martin’s studio. They gave me free rein to play what I wanted, and I came up with some interesting ideas, things they hadn’t done before, like using a synthesizer. They were very open to that, which helped me learn how to play real rock and roll. Before that, I’d been playing soul and progressive rock. This was real rock—music to make people get up and dance, with good lyrics and arrangements. It was a total pleasure. The album was made easily and quickly.

We also made a live album, half of which was recorded on Broadway. We were the first rock band to play on Broadway. The other half was recorded at the Hammersmith Odeon in London. Toward the end of my time with Mott the Hoople, we did a tour of England with a young band called Queen, who opened for us. We did about 20 shows in England and 20 in America, so we got to know them pretty well. We never thought of them as rivals or a threat; they were different enough that our fans could enjoy them as much as us. Queen took off pretty fast from there, and they’ve been good to us. Brian May, in particular, is a staunch Mott the Hoople fan and occasionally plays with us. Four years ago, we did a reunion tour, and Brian joined us in London. That was another great experience.

And how did the second Morgan album come about?

Well, like I said, the first album sold reasonably well, so RCA Italy decided to give us a chance at a second album and offered me the chance to do a solo album too. It was a lot of work since we were recording the second album and my solo album simultaneously in Rome. But I think we got a bit too avant-garde for their taste, so they passed on both the band and solo albums.

Then, in 1978, Cherry Red Records, a new young label, asked if I had any unreleased work. I mentioned the unreleased second British Lions album, and Cherry Red released it as their first album. They’ve done well and are still around—one of the longest-running indie labels. They did a good job, sold a decent amount, and asked me to do more solo work with them.

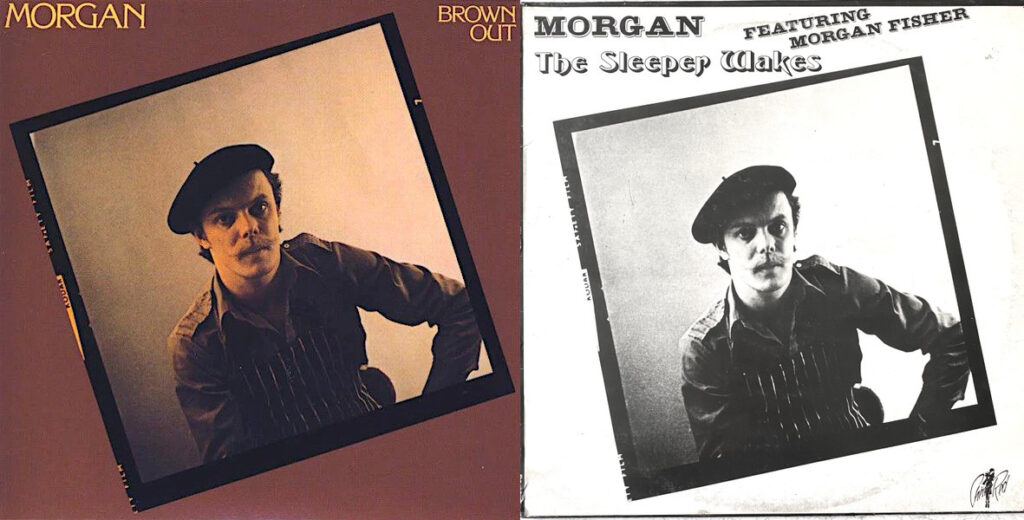

The second Morgan album was initially called “Brown Out,” which was a bit of a joke on our part, but it was picked up by an American label called Passport and released in ’76, three years after we recorded it. Later, it was reissued under its proper title, ‘The Sleeper Wakes,’ after one of the songs. I’m very proud of those two Morgan albums. My solo album, ‘Ivories,’ also came out years later and has been reissued a few times. It’s all available now, of course, online as well.

“I think I just absorbed it all, like a child learns language—by immersion, by osmosis”

Tell us about your solo career, which I guess started with the release of ‘Centuri Maya Nexus.’

Well, it didn’t really start with ‘Centuri Maya Nexus.’ That was just a one-off project. I think it was in 1972, for an avant-garde event at the Institute of Contemporary Art. They decided to make it into a single record, which is incredibly rare now. I used mostly synthesizers and remixes of outtakes from the Morgan band recordings. But, really, my solo career didn’t start until the end of British Lions.

When British Lions finally went down and punk was happening, I really enjoyed the energy of punk. I got to know some of the bands like The Clash and The Damned, and I used to go to punk clubs at least once a week to see what was going on. I just loved the atmosphere, and it encouraged me to go into more of a DIY mode instead of working the way I had for the past 10 or 11 years—with big record companies, big budgets, big studios, all of that.

Seeing the punk bands, I realized you didn’t need all that. You could do it yourself, like homemade. Luckily, at that time, home recording equipment was just good enough to make an album in your bedroom. It was still about having the right kind of tape recorder, mixer, speakers, etc., but they were just about becoming affordable. So, I bought a 4-track recording system and set it up in a small apartment in Notting Hill Gate. I was very focused on it.

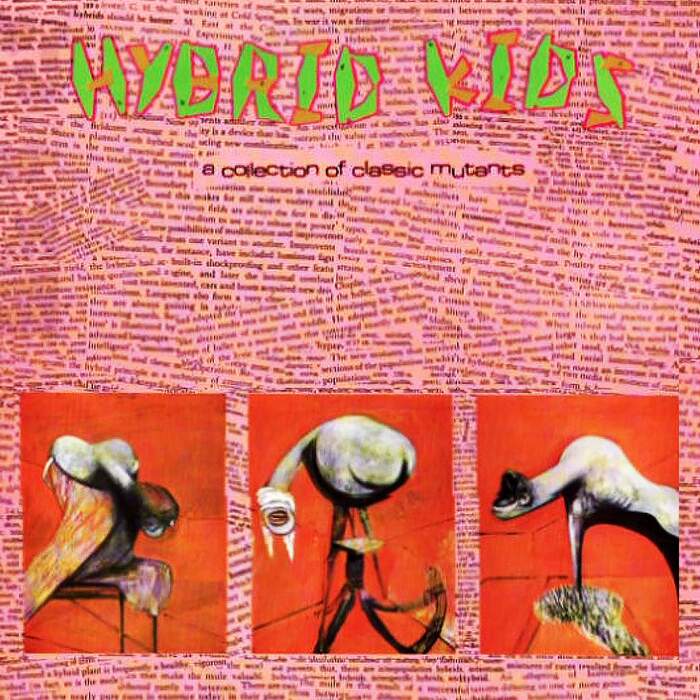

I’d been in a house before, but I decided I didn’t need a house—just one small room where I could record and sleep in the same place, and get down to doing the things I wanted. I decided not to look for another band or a record company or manager, but to go it completely alone, and I came up with some pretty mad ideas. It was almost like my creativity had been capped for years and now just exploded into a bizarre selection of ideas. The first one was an album called ‘Hybrid Kids,’ where I did strange cover versions of songs I liked, often in a style diametrically opposed to the original.

For example, I turned ‘MacArthur Park,’ a big ballad, into a ska-beat song in the style of 2 Tone Records. Just for fun and to experiment musically. I played multiple instruments—guitar, bass, and vocals. I didn’t have a drum machine and didn’t much like the sound of them, so I used drum recordings from friends’ albums, cutting them up into loops and arranging them to fit my ideas. This was all done in my little flat in Notting Hill, and it was very exciting.

In other words, I was the musician, arranger, engineer, and even designer for the album cover. Cherry Red Records, who had released the second British Lions album, were interested in what I was doing and offered to release it. It was a small, friendly label, nothing like the big companies like CBS or RCA, and I felt good about that. Somehow, the albums paid for themselves, as there were almost no recording costs. In fact, on one album, I listed the total budget as £25, just the cost of the tape—and that was true.

The feeling of going into a room, making something all on my own, then coming out and saying, “Listen to this. This is my own work,” was amazing, like a painter or poet working solo. I thought, well, musicians can do it now too. That realization really energized me creatively. I went on to make two Hybrid Kids albums. They’re pretty bizarre, and a lot of the tracks are on YouTube. My discography has accurate descriptions of each album, so I won’t go into all of them here, but it’s worth checking out.

I also got into some odd collaborations. I worked with Neil Innes, who wrote music for The Rutles and The Bonzo Dog Doo-Dah Band, and another eccentric, John Otway—definitely worth looking up. I got into more eccentric music that suited me perfectly.

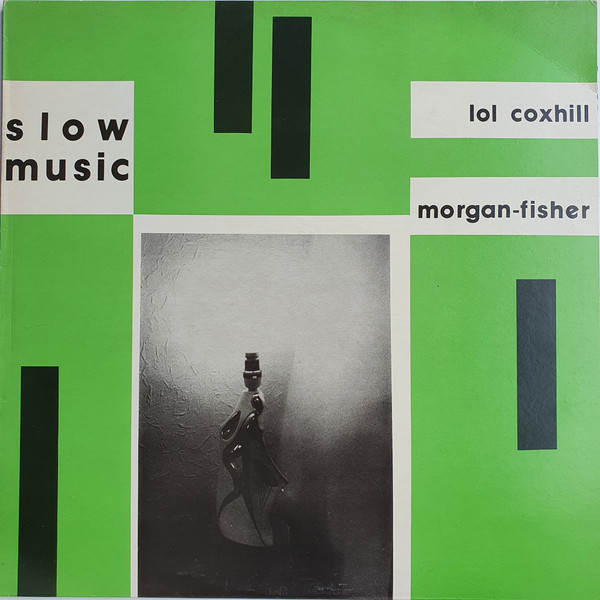

Then I made my first ambient album, ‘Slow Music,’ in 1980, which I’m still proud of. It wasn’t a synthesizer album or anything like that. I recorded the playing of a wonderful free-jazz sax player named Lol Coxhill, then edited, looped, and experimented with it. A bit like Brian Eno’s Discreet Music, where he recorded and looped Robert Wyatt’s piano. I spent about two weeks straight working on tape loops and mixing, and it was very satisfying. Cherry Red released it, and from there we had a great relationship—they basically said they’d release whatever I wanted, without big advances or pressure.

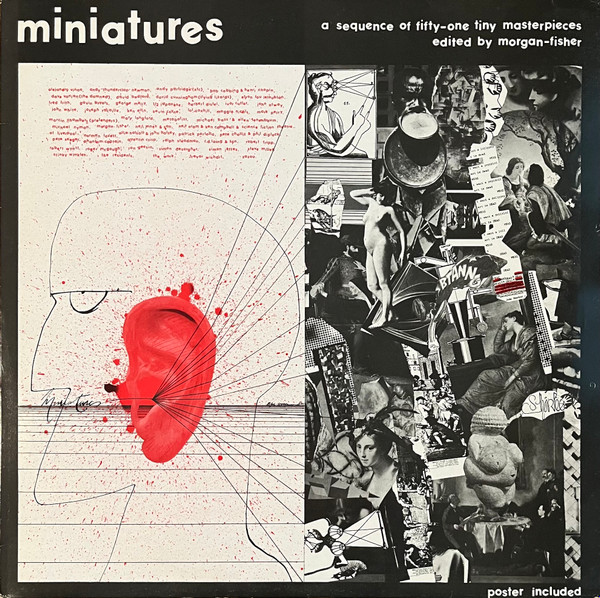

After doing three albums alone, I wanted to collaborate with other musicians. I made a long list, but it got to about 50 names. I realized I couldn’t choose just one and thought it would be nice to have everyone on a record. But I had no money, a tiny studio, and it was even hard to fit one other person in there. Then I thought, why not ask each person to make a one-minute piece of music? With 50 minutes of music, I’d have a full LP.

So, I started this project, which I called Miniatures. I was very hands-on, sending blank tapes to people and asking them to put something on. For those without home studios, I’d bring my portable recorder to their homes. I recorded with people like Robert Wyatt, Ivor Cutler, and Quentin Crisp. It took about a year and was tremendous fun meeting all these people. Some, like Robert Fripp and the drummer from The Pretenders, could record their own tracks.

The project wasn’t limited to avant-garde music; it was a cross-section of styles—poetry, humor, pop songs, and experimental pieces. The inspiration for it was Pete Seeger’s ‘Goofing-Off Suite,’ where he played classical pieces on a solo banjo. I even closed the album with his version of Beethoven’s ‘9th Symphony,’ which added a great touch. Miniatures was released in 1980, was well-received, and became a bit of a classic. People still talk about it, and it’s had many reissues. Some others have tried copying the idea, but they tend to stick to avant-garde music, which makes their versions feel underground. Mine had that eclectic mix.

In 2000, I made ‘Volume 2,’ 20 years after the first, and included 60 artists since CD format allowed more space. By then, it was more international, with artists from Russia, China, and Brazil. In 2020, people asked about doing a ‘Volume 3,’ but it’s a huge amount of work, and I decided I wasn’t ready to commit. However, I gave my blessing for others to do it. They called it Miniatures 2020 and put out a double CD with 124 tracks—a massive undertaking. I’m glad I passed on that one!

So there are now three Miniatures albums. I suppose the next one would be due in 2040, but I don’t think I’ll be around by then. If I am, I might just have to do it to celebrate still being here!

What’s it like to work with Tom Guerra?

Well, a complete pleasure, of course. Tom is one of many artists with whom I’ve done remote sessions. In other words, they send me a song that they’re recording via email, and I add some keyboards here in my home studio in Tokyo, then send it back. It’s a very easy and convenient way of working, especially since the pandemic—more and more people have embraced it. I like it because I don’t have to go anywhere, and I have all my keyboards here, so everything I need is right at my fingertips. That’s the beauty of computers, and I’d definitely like to do more of this kind of work. Please put the word out—I’m definitely available at any time for all kinds of music that need keyboards. And Tom writes great songs. He plays great guitar, so it’s very easy for me. He’s definitely somewhat in the style of Mott the Hoople, which feels familiar to me.

We actually have met because I’ve been to New York a couple of times, where he lives. We’ve still not actually played together physically, but he came to see me give a talk about Mott the Hoople in New York, and we hung out a bit then. I’ve played on three or four of his albums by now. The songs are good; they’re very emotional. I’d say there’s an influence from Ian Hunter, but Tom has his own style. The other musicians on his tracks are all very good, some of them quite well-known. It’s just a pleasure, and he gives me, again, carte blanche. I like it if people have some ideas so I can get a sense of the approach they’re after. I might play something, send it to them, and then we discuss it, and I might tweak it a bit. But it usually goes fairly quickly. I’m getting great comments from everyone I’ve worked with this way, and I’m definitely looking forward to doing a lot more of these remote sessions.

What currently occupies your life?

Well, remote sessions are certainly part of it. I also have a 55-year career now, with a lot of recordings and archive material I’ve stored up, some of which I’m remixing. For example, I played 100 solo concerts at a club called Super Deluxe starting in 2003 through 2013. It was a monthly gig where I completely improvised. By that time, I’d acquired a lot of unusual vintage keyboards, and I’d take different ones to each show and just start improvising. Something always happens, and it’s a very satisfying way to make music. When I say improvisation, I don’t mean random chaos like some free jazz. I mean starting from silence and maybe playing one note to see where it leads.

Doing it so often, I’ve realized this is basically the key to composing—melodies come from nowhere, but you have to know how to invite them. So when I do this process, it’s like composing in slow motion. A melody appears, and I use a looper to layer and repeat, adding more elements as I go. The process sometimes evolves into long, 45-minute improvisations. I’ve recorded all of them—I call the series ‘Morgan’s Organ.’ I’ve edited some and put them up on Bandcamp, and that takes up quite a bit of my time.

I’m also working on a ‘Mott in America’ DVD. I shot some footage when I toured with Mott on an 8mm camera, and I made a DVD of it for the 2009 Mott reunion tour. I wasn’t part of that tour because it was only the original five members, but I went to see them play, which was a great pleasure. Lots of old friends came from all over the world. Now I’m working on a 50th-anniversary edition of the DVD. There’s amazing software available now that can enhance old 8mm footage to make it look almost like modern video. I’m adding new music, narration, and some extras. It’s time-consuming, but I hope to finish it before the end of the year, as this is the 50th anniversary.

Who are some important players who influenced you?

Keith Emerson was one, as I’ve mentioned. He did more with Hammond organ than perhaps anyone else, not just with his classical-style speed but in making it produce different sounds. He did things like bending notes by switching the organ off and on quickly to make the pitch dip and rise, and creating thunderous sounds by shaking it to affect the spring reverb inside. He used synthesizers melodically rather than just weirdly, which I loved.

But any musician who has a broad view is influenced by everything they hear. I can name names I got into early on when I was just a teenager, sitting at home and thinking, “There are things here I can take.” People like Ray Charles, Jimmy Smith, Booker T., George Shearing, Dave Brubeck, Alan Price from the Animals, and Rod Argent of the Zombies—they were so far ahead of me, and I learned a lot from them. What I liked was that they could be experimental yet still melodic. They didn’t dive into elitist, avant-garde realms where only a few people could understand. The Beatles were like that too—they could do bizarre things like ‘Tomorrow Never Knows,’ and yet it wasn’t too far out for the public to enjoy.

Mott the Hoople was also like that, and I wish we’d stayed together because we were moving into new areas with The Hoople. I thought we could’ve gone even further, especially when Mick Ronson joined us. He was incredibly creative, and his two solo albums are amazing. We only made one single together—Saturday Gigs, which I’m very proud of.

Beyond that, people like Walter Carlos, Pink Floyd—they showed endless ways of using keyboards. All of it comes out at different times. I think any young musician should absorb everything, all types of music. When I was a teenager, I’d lie in bed for hours with headphones on, putting on record after record. I’d go to the library and check out all kinds of records, from Stockhausen to the Animals, and just listen. Nothing beats that. I never studied music formally; I didn’t go to music college. I think I just absorbed it all, like a child learns language—by immersion, by osmosis. To me, that’s the best way to learn music or any creative thing, or even another language.

I learned Japanese by being here. I’ve hardly picked up a book on it. I had a few lessons, but I gave them up. I just don’t like forcing things into my head. That’s how schools worked back then—forcing in information you’d forget immediately. I think you learn best by being like a child. Picasso said it: Remain childlike, but not childish. Immerse yourself, let things soak in.

Klemen Breznikar

Morgan Fisher Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube