Haydn Larson: Exploring the Avant-Garde with The Familiar Ugly and Red Krayola

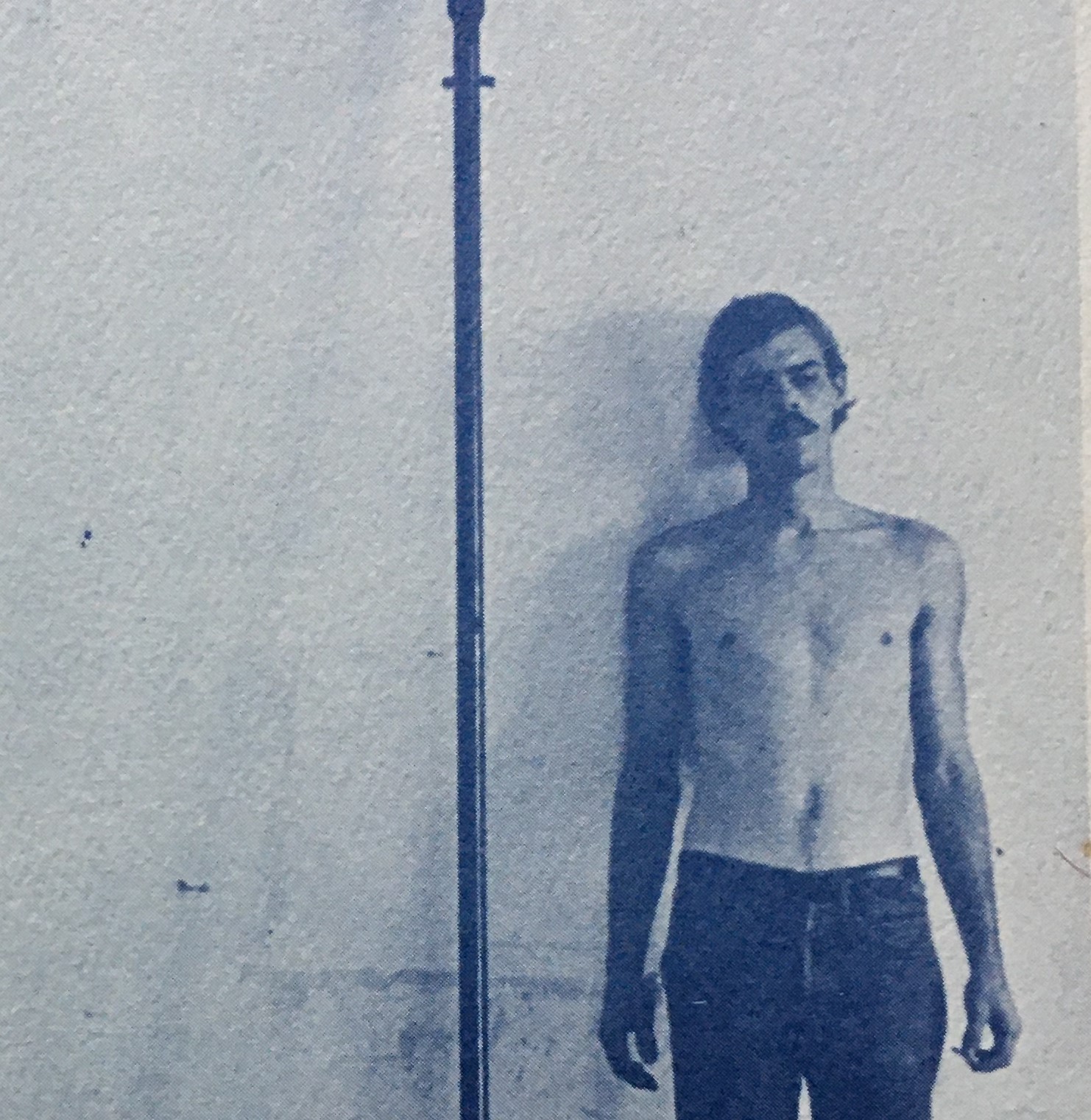

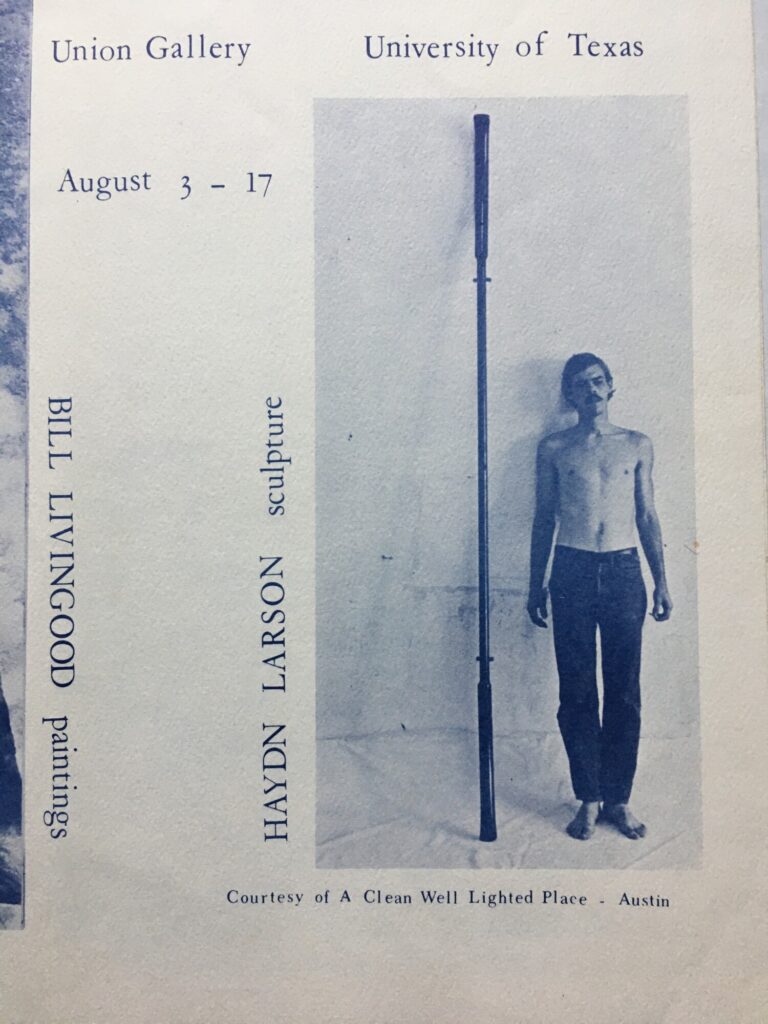

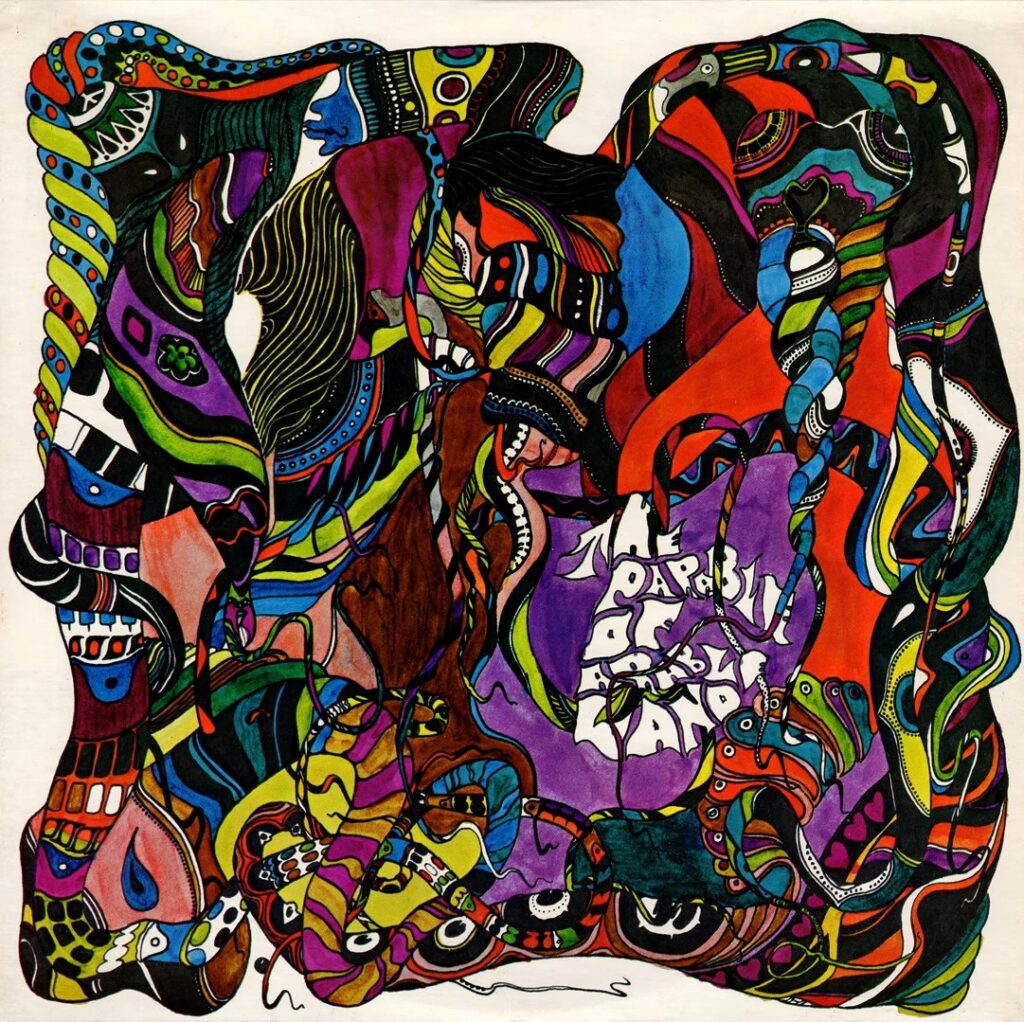

Haydn Larson is a lifelong artist deeply rooted in the countercultural explosion of the ’60s and ’70s. As a member of the influential group The Familiar Ugly, he collaborated with the avant-garde band Red Krayola, contributing to their groundbreaking album that challenged the status quo of artistic expression.

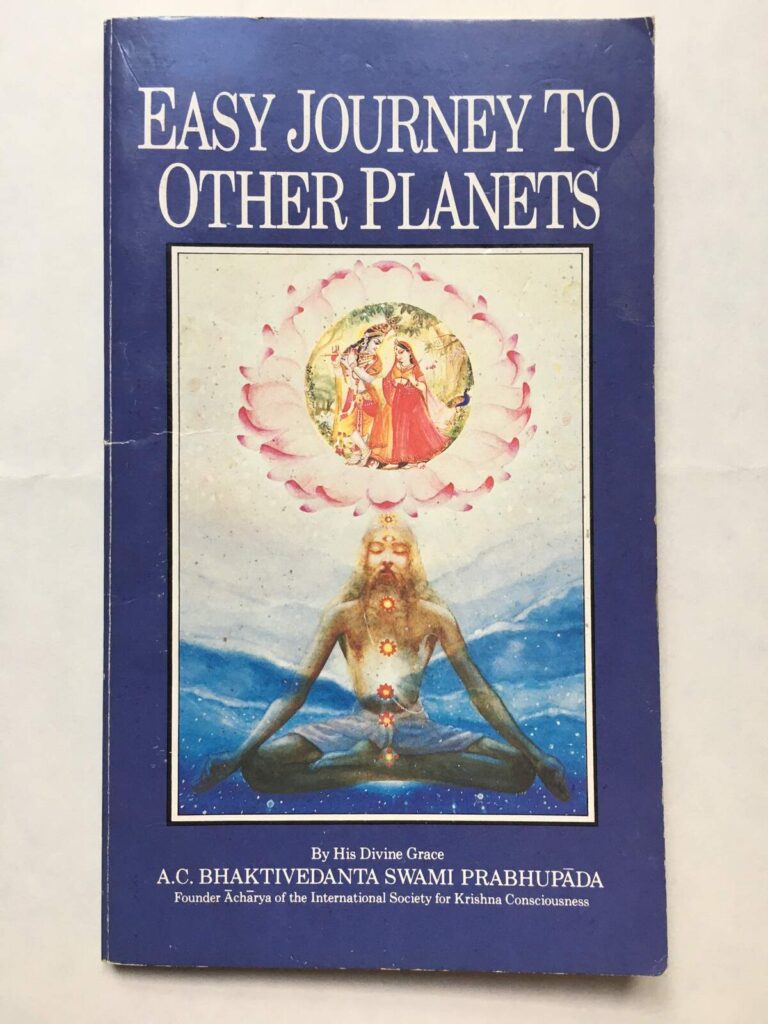

After his early musical endeavors, Haydn embarked on a transformative journey to India, where he studied sculpture and eventually established multimedia museums dedicated to spiritual texts like the Bhagavad Gita. Today, he juggles various artistic pursuits, from sculpting deities to writing poetry and zines, all while sharing a studio with a talented artisan who crafts electric basses. With a fierce commitment to his art, Haydn continues to inspire those around him, including his two creative daughters who are following in his footsteps.

“Early on, I developed an interest in art and music.”

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Haydn Larson: I was born and raised in Houston, Texas—born in ’46. I grew up in a pretty typical, lily-white suburb. Early on, I developed an interest in art and music. My early influences in music were, of course, the Beatles and the Stones. There was a radio station in Houston back then—an FM station that usually played only classical music. But at night, they had this group of DJs who would play rock and roll albums back-to-back with no commercials. It was commercial-free radio, and that really opened my mind. I heard a lot of music that I hadn’t been exposed to before. And with artists like Bob Dylan and The Beatles moving away from “teeny bop” to more serious subject matter, I realized that music could cover a lot of ground and be so many things.

I graduated high school and went on to college at the museum school in Houston, which was an unaccredited art school. I also took classes at the University of St. Thomas, which was nearby. St. Thomas was a Catholic school, taught by priests, but it was overseen by Dominique De Menil. She and her husband made a fortune selling oil equipment in Texas, but she was also a prominent art collector and supporter of modern art. This little liberal arts school became her way of introducing art, music, film, and all things modern into the students’ lives. It was great to be part of that environment.

Daily life…well, I went to religious schools—Episcopal schools—up until the seventh grade. Then I switched to public school, which was eye-opening. I got to meet all kinds of people, different types of students. I started taking art classes, joined the band, and studied drums. I was in a marching band. My dad took me to a movie about Gene Krupa once, and that really left a mark on me. After that, I wanted to be a drummer.

I also loved art—the Impressionists and Abstract Expressionists especially. My mom taught at the museum school, which was part of the Houston Museum of Fine Arts, so while she was teaching, I was free to roam around the museum. I got to know the guards there, and they introduced me to all kinds of artwork. Later on, I even worked for the museum for a time. Those experiences really fueled my interest in art. Aside from rock and roll and girls, there wasn’t much else I was interested in back then.

So how did your love for music really start?

It all started with Gene Krupa. And then, a friend introduced me to Bob Dylan’s first album. Of course, the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show was a big deal too, like it was for everyone. I was lucky because my friends were also into music. They collected records, and we’d share albums with each other.

Tell us about some of the early projects you were part of that eventually led to The Familiar Ugly…

As I wrapped up my high school days, I got the chance to visit some pretty iconic places—La Maison and another spot called The Cellar, I think. They had live music, and it was a real eye-opener. I got to see bands like the 13th Floor Elevators and many others that were just starting to make waves in Houston, Texas. A bit before that, I’d go to these folky coffee houses around town, where I’d listen to folk singers—most trying to channel Bob Dylan, but some of them were actually good.

“I remember we went to see Frank Zappa, which was unforgettable”

All of this was in Houston?

Yes, in Houston. Eventually, all of this led me to the University of St. Thomas. I also spent a summer in Maine at a place called Skowhegan. I received a scholarship, which took me up to New York first. A young lady there showed me around the city—I’d never left Texas before that—so she took me to all the museums. I remember we went to see Frank Zappa, which was unforgettable. Afterward, I went on to Maine, where I spent an incredible summer with some of the best young artists of the time. The school would bring up prominent artists from New York to spend a week with us, each taking turns. It was all so immersive. Merce Cunningham even came with John Cage—that was fascinating.

By the time I returned to Texas, the first thing I wanted to do was leave home, and the second was to move to Austin. I was set on going to New York, but I’d have been drafted if I did, so Austin was my second choice. I decided to study art at the University of Texas.

So you weren’t tempted to join Red Carillo?

No, that wasn’t exactly high on my list!

Tell us about some of the early projects you were part of that eventually led to The Familiar Ugly. How was The Familiar Ugly born?

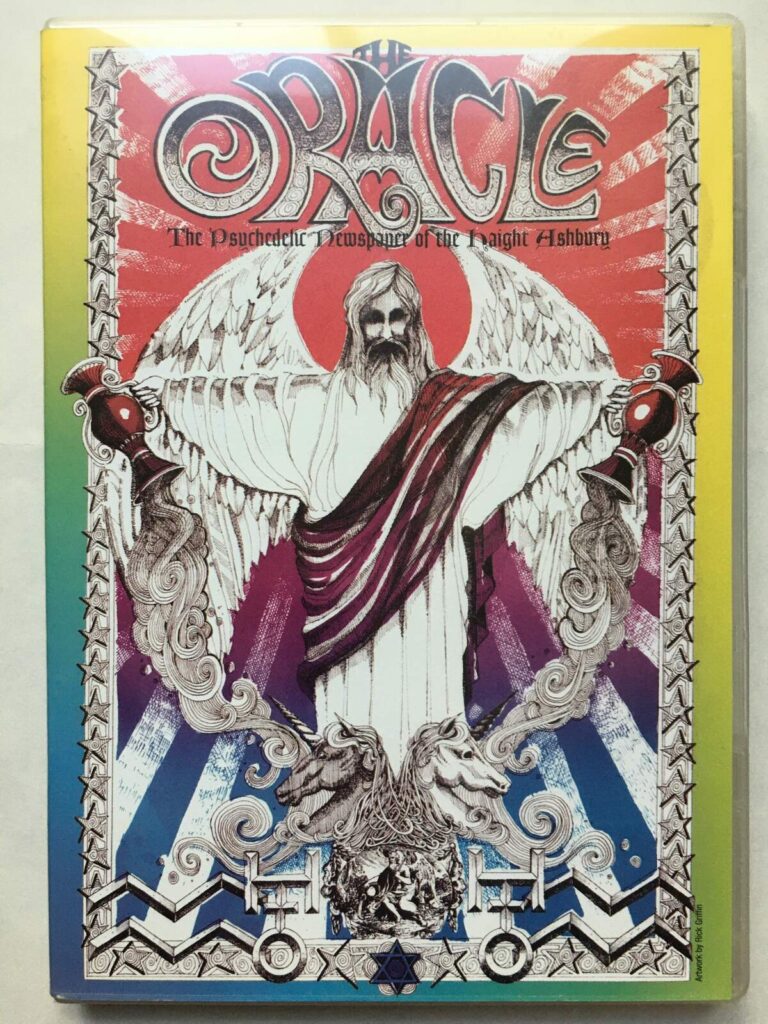

Well, as I mentioned, Dominique de Menil had this huge influence on us. She was constantly feeding us incredible information. We had Andy Warhol come in for a lecture—although he just sat there silently while a young woman spoke on his behalf. That was his thing at the time. Claes Oldenburg, a famous pop artist, also came through. She brought in various artists, and we had foreign film nights every week and our own underground newspapers. The students were so creative—everyone could write poetry, put on plays, publish underground papers, and so on. We even got to visit the homes of multimillionaires in Houston and Dallas, seeing their incredible art collections up close. It was a real privilege.

So, “we”—you mean the students? Were they the future members of The Familiar Ugly?

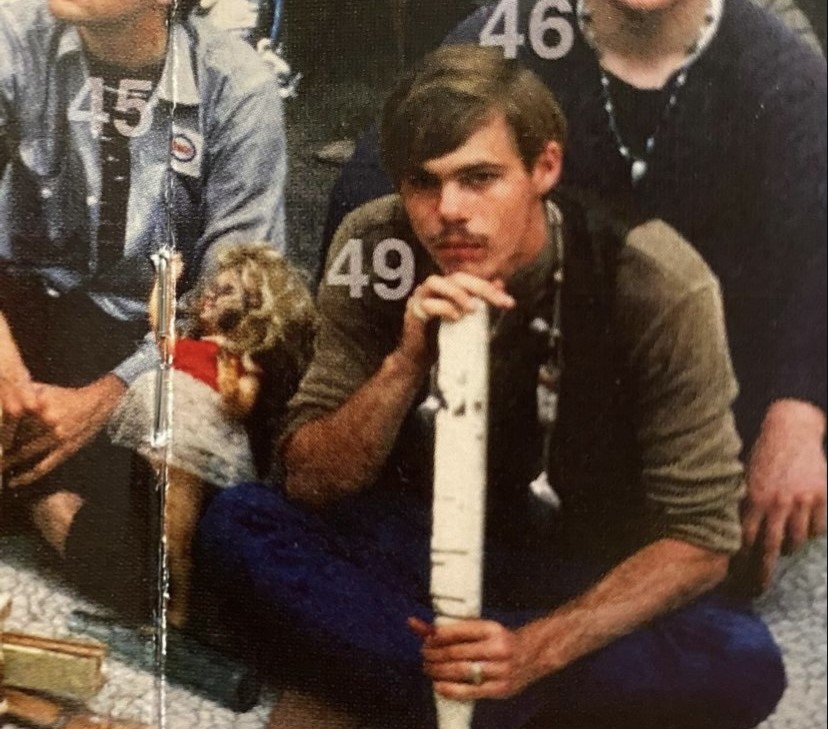

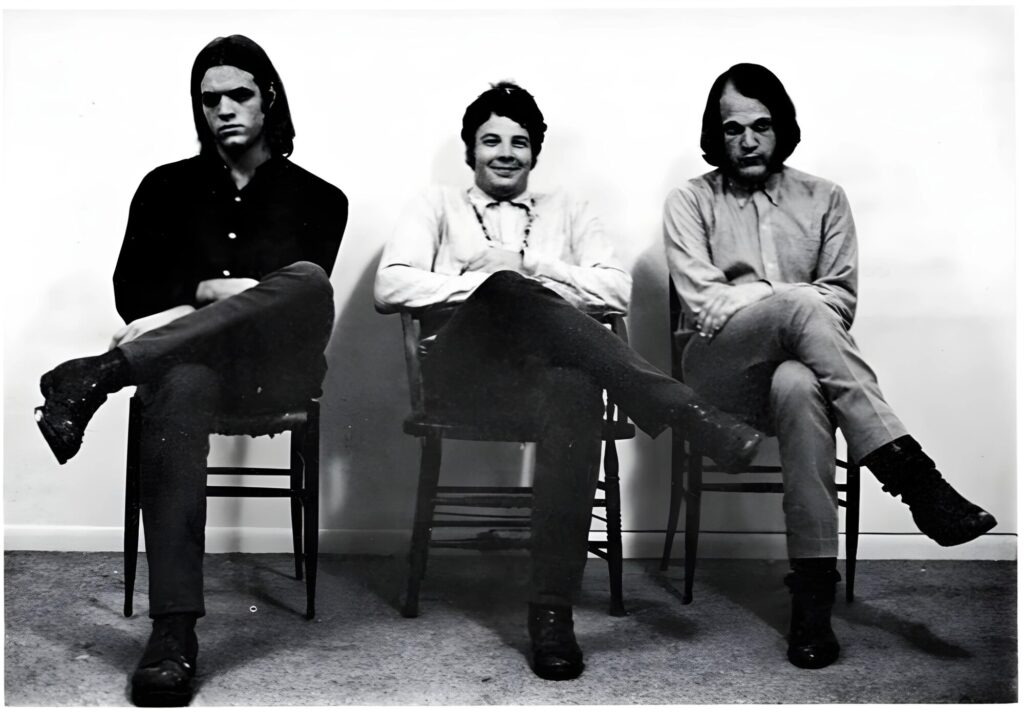

Yeah, that’s right. It was the students, and eventually, Steve Cunningham, Frederick Barthelme, and Mayo Thompson—those would be the future members of The Familiar Ugly. Having those doors open to us really shaped my idea of art. This was the mid-sixties, so there was just so much creative energy, amazing music, theater, and film. It was a perfect time to be immersed in all of that.

Do you feel like The Familiar Ugly just naturally grew out of that atmosphere?

It did, yeah. It was organic. It may have been Mayo or maybe Steve or Rick who had the initial idea, but I think they were looking for people who could balance the structure of their music with this spontaneous “wall of noise.” That’s where we came in.

Did you have any prior projects, musical or otherwise, that led to this? Or was this your first music experience?

This was pretty much my first foray into music, aside from sitting around and singing the occasional Kumbaya or singing in the church choir. But The Familiar Ugly—that was my introduction to this kind of experimental music world.

It sounds like the group was more of an impromptu ensemble for that one recording session. Did you rehearse before it?

No, no rehearsals. I knew most of the people there—at least in passing. A lot of them went to the University of St. Thomas; others were artists or, you know, beatnik or hippie types.

“Chaotic, spontaneous, and collaborative”

So why do you think they asked you?

I don’t know if they asked me directly. I think I just heard through the grapevine that there’d be a recording session at this studio at a certain time, and it was like, “Bring an instrument, and we’ll just wing it.” We made it up as we went along, which was fine with me. I think Mayo had this idea of creating a more interactive experience—something between the audience and the group that would be chaotic, spontaneous, and collaborative.

In the evolution of The Familiar Ugly alongside The Red Krayola’s musical journey, the concept of “Free Form Freak-Out” seems to encapsulate a unique form of musical expression and collaboration. Could you delve into the dynamics of how this concept shaped the creative process within the group? Specifically, how did the spontaneous inclusion of additional members, from a diverse array of backgrounds, influence the sonic landscape and overall experience for both performers and audience members? Additionally, considering Mayo Thompson’s perspective on the formation of The Familiar Ugly and the origin of “Free Form Freak-Out,” could you elaborate on how this phenomenon transcended traditional notions of form and structure within music, offering a space for unrepeated experiences and embracing the essence of “noise” as an integral part of the musical narrative?

That’s a real five-part question right there.

[laughs] Yeah.

Well, I think you could take it back to… what’s his name? Now I forget any names.

Rick? Steve?

No, no, not them. Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

John Cage?

John Cage was— I mean, I don’t know much about that part of the history of music, but, in the public eye, John Cage was like the first person to depend on or build around a kind of spontaneous sound landscape. And so, these fellows at The Red Krayola were, I’m sure, very aware of him.

It seems like you were.

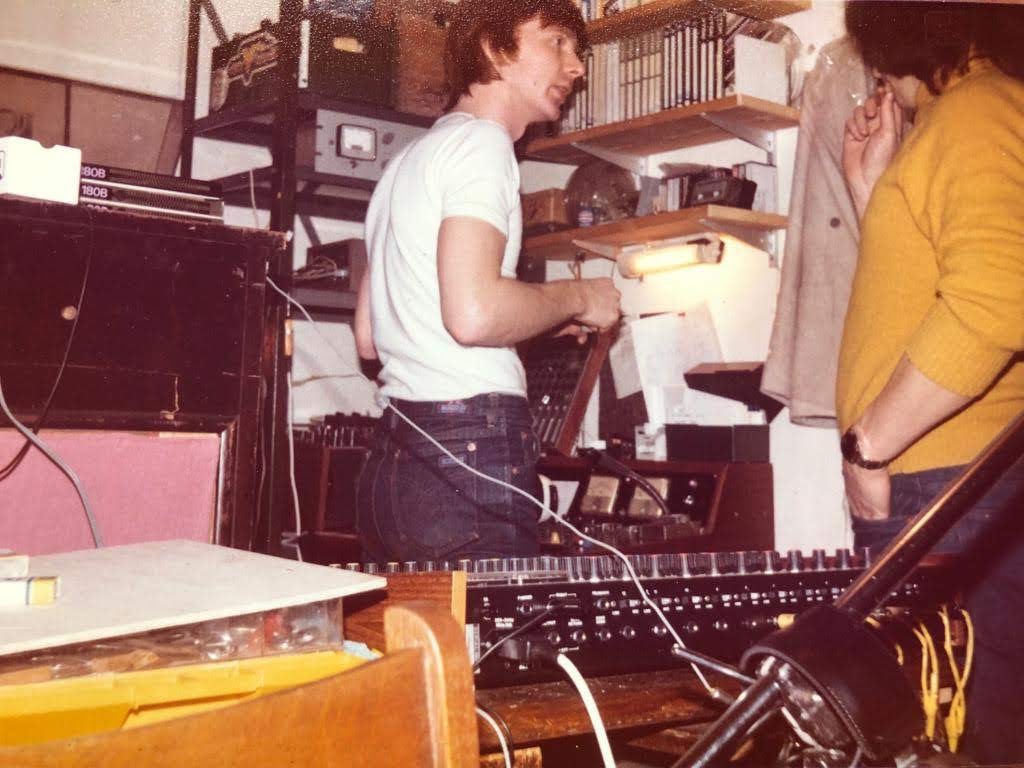

Yeah. I was, too— oh, we all were. And it was an interesting balance, I felt, to have this structure of a band, a three-piece band, and then this spontaneous noise factor. To kind of bounce those two back and forth created, kind of, an interesting tension. And I would imagine that, you know, it sort of let everybody in on the fact that we could all make music of our own devices. And so it kind of opened that door, I think.

I’m sure because of the time this album landed, there was nothing else like it. The fact that The Red Krayola did it first really kind of put them on the map. Now, you know, there was kind of some crazy stuff going on in The 13th Floor Elevators, but this was a few steps further down the road than that. Jazz had a history of freeform interaction, but this was rock and roll. So it was making a shift from a generally very structured musical collaboration to something that was… you didn’t quite know what it was gonna be, you didn’t quite know how it was gonna end up.

In a sense, it was in keeping with abstract expressionism or, some just sort of Zen spontaneous paintings. You’re trying to get around the structure of your mind into a field of just spontaneous activity. I think it went right along with the drugs that were being imbibed at that time and sort of the freeform spirit that was very much alive and well in the mid-sixties.

The inclusion of additional members, sometimes reaching up to 50 people on stage, is quite remarkable. Could you elaborate on how this fluidity in membership affected the group’s dynamics and creative output? How did it influence the improvisational nature of the performances?

I mean, I guess you kind of explained it. I can’t really say too much more about that simply because I was only involved in one performance. And that happened to be the one that landed on the album.

It’s a good performance to be involved with.

It was a very good performance. Glad to— honored to be there.

“We were just being mic’d and then set free”

Mayo Thompson described The Familiar Ugly as an organization that accompanied or enveloped the music of The Red Krayola, with membership numbers being undirected and open-ended. How did this fluid structure impact the collaborative process within the group? Did it present any challenges or opportunities for artistic exploration?

I can only answer for myself, and we were not— at least in that particular, at that studio at that time— we did not have a musical background. It wasn’t an overlay of music made by The Red Krayola. We were just being mic’d and then set free. I mean, there was a mood, I think, to express our inner angst or inner feelings. But, I think that everybody was very— there was no one person overwhelming the rest of us. It was a very interesting chorus of sounds, like a fabric without one piece sticking out any more than the rest of the fabric.

Well, I mean, you know, towards the end there was a Harley Davidson, right?

[laughs] Right, that was a little louder than some of the others.

But the rest of you were… thoughtful?

Right, I think most of us were. Just wanting to make a thoughtful sound, you might say, that would go along with or maybe counterbalance the aggression of the three-piece band.

That kind of answers the next question because it’s about how the group navigated the sense of freedom while maintaining coherence and intentionality— balancing experimentation while maintaining that connection with the audience.

Yeah, well…

But there was no audience.

Right.

But it sounds like the “Free Form Freak-Out” was almost treated as a separate entity entirely. It wasn’t like you guys were jamming with the band during the recording session. Had you heard their music before that?

Yeah.

Okay, so you’re familiar with their music and their vibe.

Mhmm.

Mayo Thompson mentioned in an interview that “Free Form Freak-Out” was coined as an advertising slogan, but he embraced it as a historical descriptor. How do you interpret the significance of this term within the context of The Familiar Ugly’s performances? How did it reflect the group’s philosophy and approach to music-making?

Boy, I have no idea what their philosophy was.

Yeah. It seems like you’ve kinda answered that already.

Yeah, well… yeah, right. I mean, the whole… the yang, right?

Exactly. Like, kinda getting out of your own mind and…

Right, right. Along with that.

Can you share any memorable experiences or performances with The Familiar Ugly that particularly stand out to you? How do you believe these moments exemplified the essence of the group and their collaborative spirit?

Well, it was a collaboration of at least the people I knew to some extent—a group that had stepped away from the mainstream in all other aspects of their lives. This was kind of the topping on the cake, or a vocal or sound reflection of their pushing away the status quo. The people I knew who were there—many of them were artists in their own right, mostly visual artists, and they were not buying the common slogans we were brought up with. They were questioning. I mean, at that time, you know, we had civil rights, we had the draft in Vietnam, JFK had just been shot a couple of years before… So there was a lot of questioning, from top to bottom, too—from art to diet to lifestyle. Just everything you could think of was being reevaluated. And this was a chance for a group of outsiders to express that feeling.

That’s beautiful.

In what ways do you think The Familiar Ugly’s contributions to The Red Krayola’s performances influenced their legacy?

Yeah. No, I think it did. I mean, it was a popular album, and I think the music itself traveled to both coasts and let it be known that there was, you know, another coast.

And that widened the purview of what could be and should be artistic expression. In that way, I think it was very successful.

Well, plus, it seems like it traveled beyond the coast. I mean, I heard about it from Pete Kember in Sonic Boom—that was in England.

Yeah, yeah. So it did have an impact, and I think a good one. Like any art, any creative expression is built on the expressions of the past, in most cases. This allowed a lot of people coming into music and the arts to look at that and say, “Whoa, this is possible. This can be done.” Hopefully, it spawned noise and other genres—and I’m sure it also helped spawn punk. Definitely. There are threads that lead back to the Red Krayola that are still prevalent today.

What followed for you? Were you still musically active?

I was definitely an avid music appreciator. I went to Austin after that. There was a place there called the Vulcan Gas Company that brought in musical acts from all over. I got to know some of the people there, especially Jim Franklin, an illustrator who created all their advertising.

At the Vulcan Gas Company?

Yes, at the Vulcan Gas Company. Austin was another pivotal place—a lot of young people from other parts of Texas and the South escaped there to experience the creative atmosphere. It definitely influenced and helped me. I went on to create sculpture and drawings, and it just expanded my vision of what could be.

It kind of opened me up personally to the idea that there were a lot of people questioning things on this level of existence. But for me, it opened doors to even bigger questions: What’s next? What am I here for? What’s the purpose of life?

Sure.

Those were questions I kept asking, asking more and more people. Eventually, it helped me join a yoga community, go to India, study sculpture there, come back, and put together two multimedia museums that illustrated books like the Bhagavad Gita and the Srimad Bhagavatam.

Where can we find those museums?

One is in LA, and one is in Detroit. That experience set my life on a path that wouldn’t have existed without those years in that crucible of creativity at the museum school, at Rice University nearby, and at Saint Thomas. All the people we connected with there were in a small area. I could walk to any of these places—they weren’t far apart. Everyone lived in that area, rents were cheap, and we all got to know each other. It was a very sweet place to plant seeds and grow your vines of creativity, you know?

Is there any unreleased material you are part of?

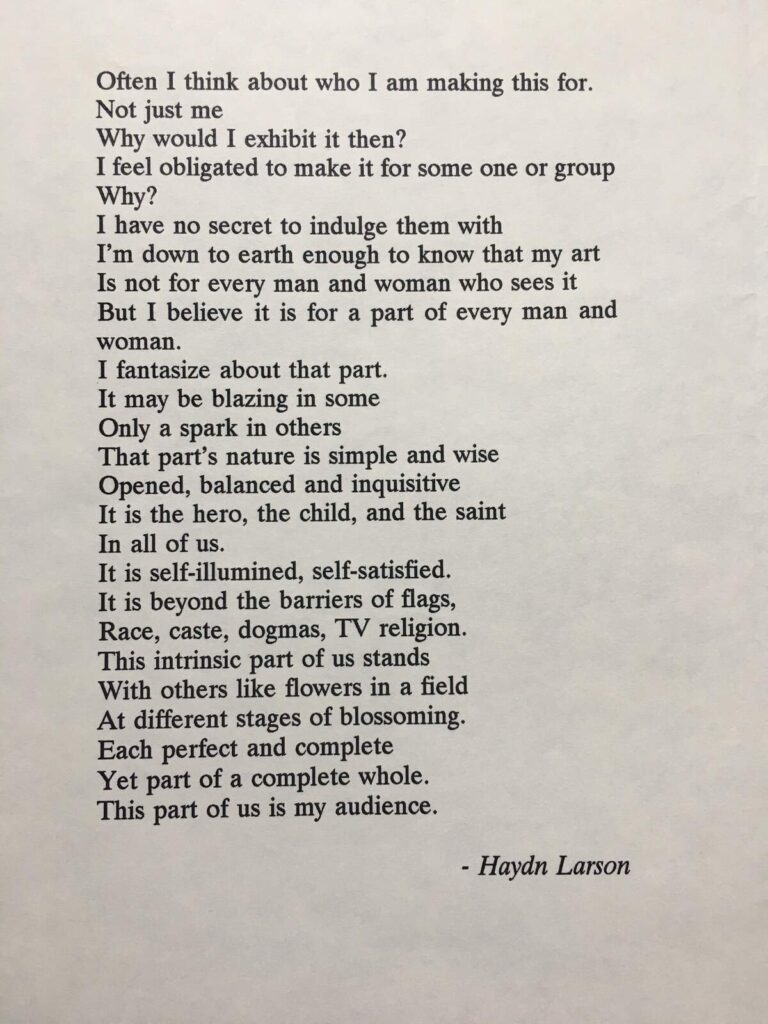

I have a lot of unreleased paintings. Maybe some unreleased poetry? I have a lot of unreleased poetry, yeah.

What currently occupies your life?

I’m working on a couple of projects. One of them is recreating an atmosphere that was alive in 1966–67 on the Lower East Side of New York City. It was a tiny little temple. We’re going to try to recreate that atmosphere because it was the seed for the explosion of the Hare Krishna movement in the West.

I’m also finishing a deity that will be enshrined in a temple, and working on a few other projects. I’m writing poetry and creating zines that I give away and put around here and there. I published one book of zines, and I’m getting ready to hopefully produce another one—just my thoughts and poetry. And what else? Raising two incredibly creative young ladies, one of whom is sitting next to me right now. She’s a force to be reckoned with—unstoppable creative energy that I love being around because she really inspires me.

I have a studio that I bisected, and I share it with a fellow on the other side who builds electric basses, electric short basses, and ships them all over the world. Beautiful works of art in themselves. So yeah, I’m very busy.

Well, looking back—oh, sorry. Was there more?

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band?

I think the highlight was right there. It was in that hour and a half, two hours of just reaching into our innermost selves and trying to put that out there in a thoughtful way. Yes, that was a highlight.

Just to be associated with those people—they were pioneers of a whole social movement in the Texas area. Of course, we were being bombarded by influences from either coast, but these were people following the beat of their own drum. They were very creative, very magnetic, and they had an influence on many others.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

I appreciate what you’re doing. You’re digging up amazing bands that may have been short-lived, but each one fed into that bigger crucible of creative sound. For you to dedicate yourself to that and present it to the world in such a palatable way is very commendable. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you for what you’re doing.

Klemen Breznikar

A heartfelt thank you to Taraka Larson for making this possible.

Haydn Larson Official Website / Facebook / Instagram

Red Krayola | Interview | Mayo Thompson