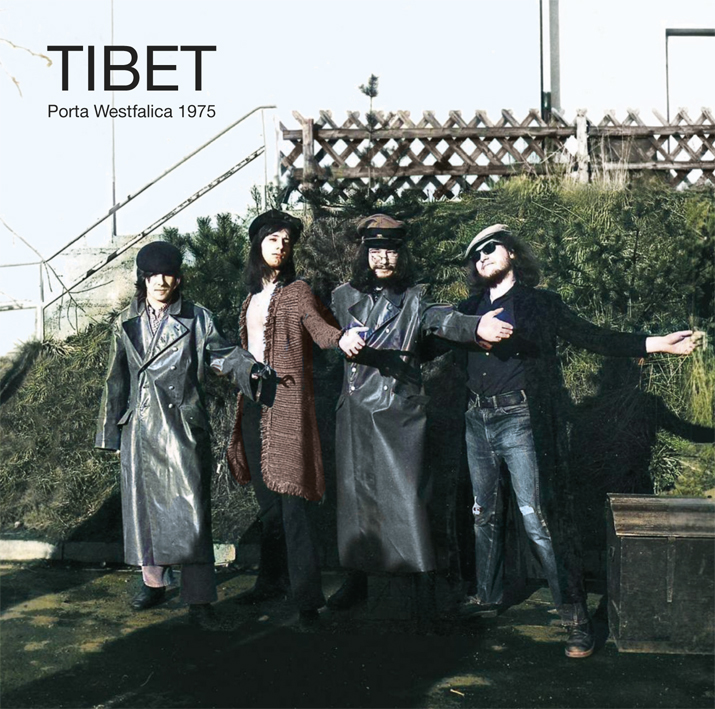

Rediscovering Tibet | A Lost Gem of 70s Progressive Rock

Tibet, the progressive rock band from Werdohl in the Sauerland, was founded in 1971, but their musical output remained sparse until the late ’70s.

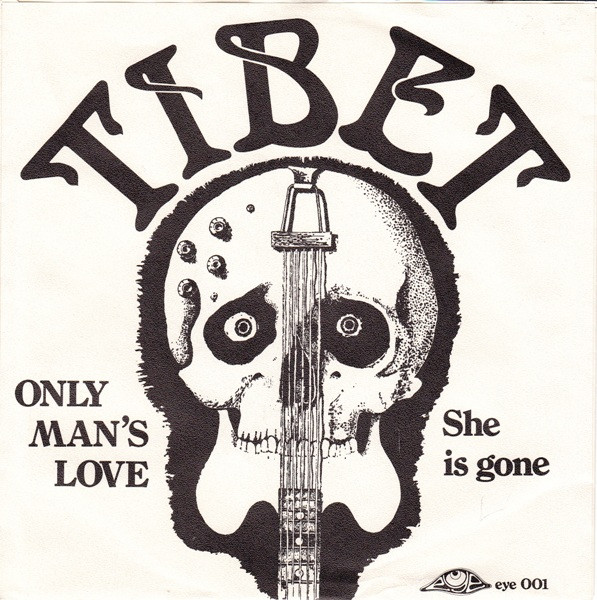

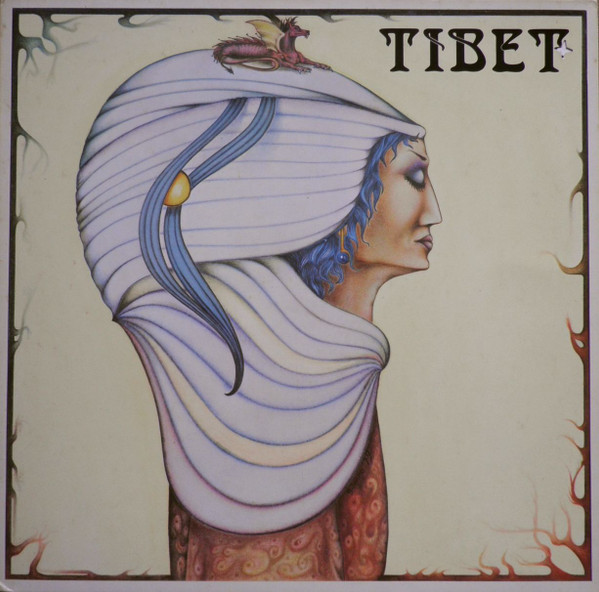

They released their only 7-inch single in 1976 and their sole LP in 1979. A rare and previously unreleased live performance from 1975 at the Goethe open-air stage in Barkhausen has recently been remastered by Eroc, and issued by Garden of Delights, offering a pristine version of the instrumental set. Only the final two tracks are sourced from different recordings, but the remastered CD sounds impeccable. An LP edition of the performance is in the works, though it will exclude the bonus track due to limited space. Notably, the 32-page CD booklet includes a compelling reflection by guitarist Jürgen Krutzsch on his time with the band. This new release gives listeners a chance to experience Tibet’s unique sound, which blends classic progressive rock influences with their own distinctive approach. Fans of the era will find this live performance, including the known track ‘Fight Back,’ a treat that reveals the depth of Tibet’s creative potential.

“Each of us lived in our own world”

It’s great to have you. Are you excited about the recent Garden of Delights release of your material from 1975?

Jürgen Krutzsch: Thank you for the invitation. Of course, that’s something none of us had expected. We didn’t even know that the performance had been recorded.

Hearing your old recordings today, what runs through your head?

The first thing you realize is what could have been done better. And then you realize that there is still so much material from that time that we would like to record again. That’s where we started, even before we found out about the old recordings.

Would you like to share something about your adolescence? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years. What was life like in post-WWII Germany?

The four musicians (plus mixer and lighting man) from the early days (1971) were all from Werdohl, a small town in the Sauerland, not very far from Dortmund. They were all from normal working-class families—there were large metal-processing companies in Werdohl at the time—only I came from the gastronomy industry. We had a restaurant, which I turned into a music pub after my father’s death, and it achieved cult status. There wasn’t much happening in Werdohl; you had to travel to bigger towns to experience something.

Was there a certain scene you were part of? Maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of concerts back then?

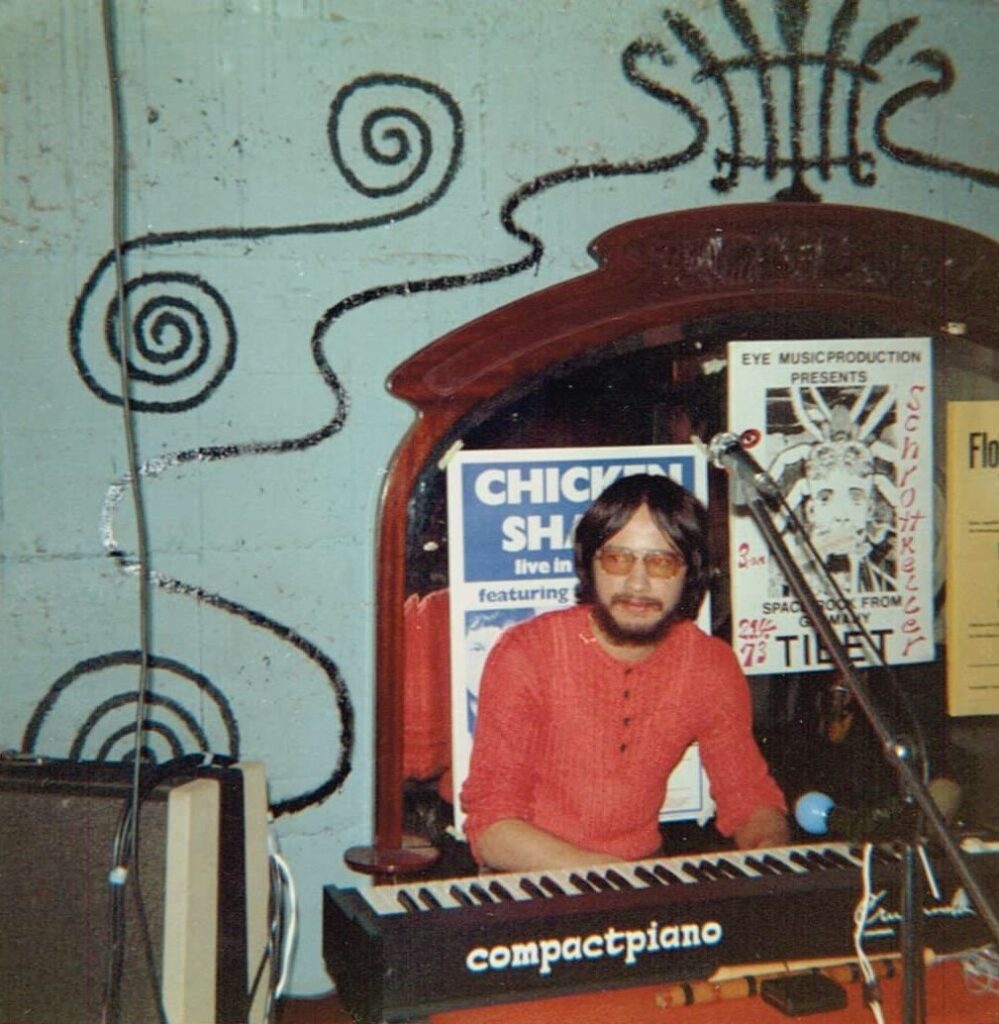

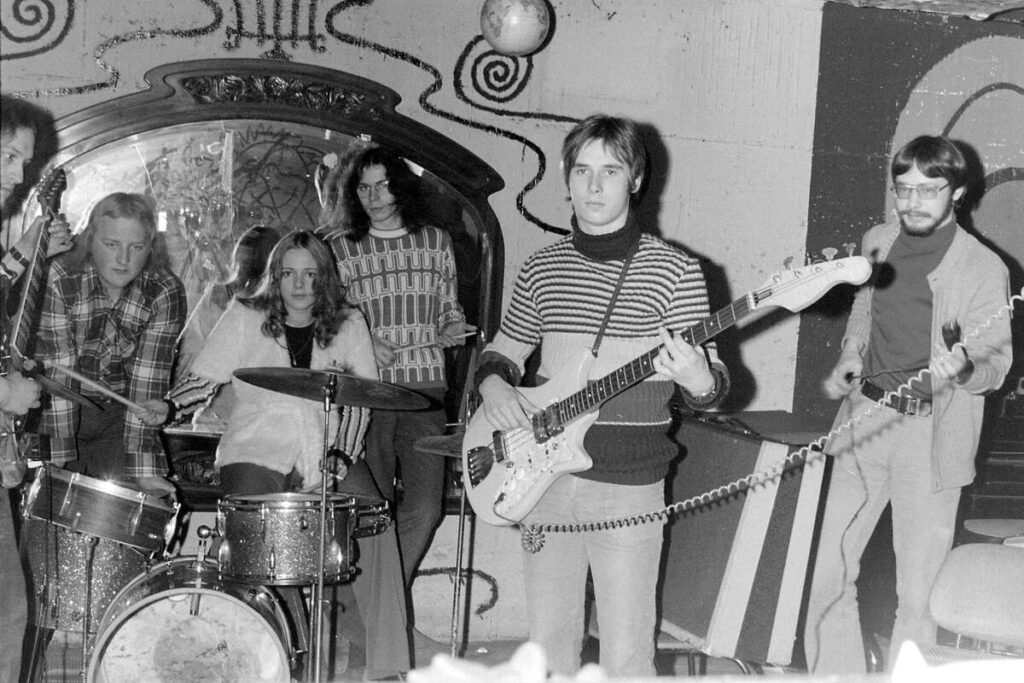

There was only a small scene community, and you usually met them in Lüdenscheid, 10 kilometers from Werdohl. But there was a youth club in Werdohl called Schrottkeller, which also had cult status. There were live concerts there twice a month, and although the club wasn’t big—maybe an 80–100 person capacity—you could see groups there that were already pretty well-known in Germany. I almost always went to live concerts there, and so did some members of Tibet. Teppich (our drummer) had moved to Wetter (near the Ruhr area) in 1975, where he met his wife, to whom he is still married today.

Tell us about some of the very early bands you were part of before Tibet.

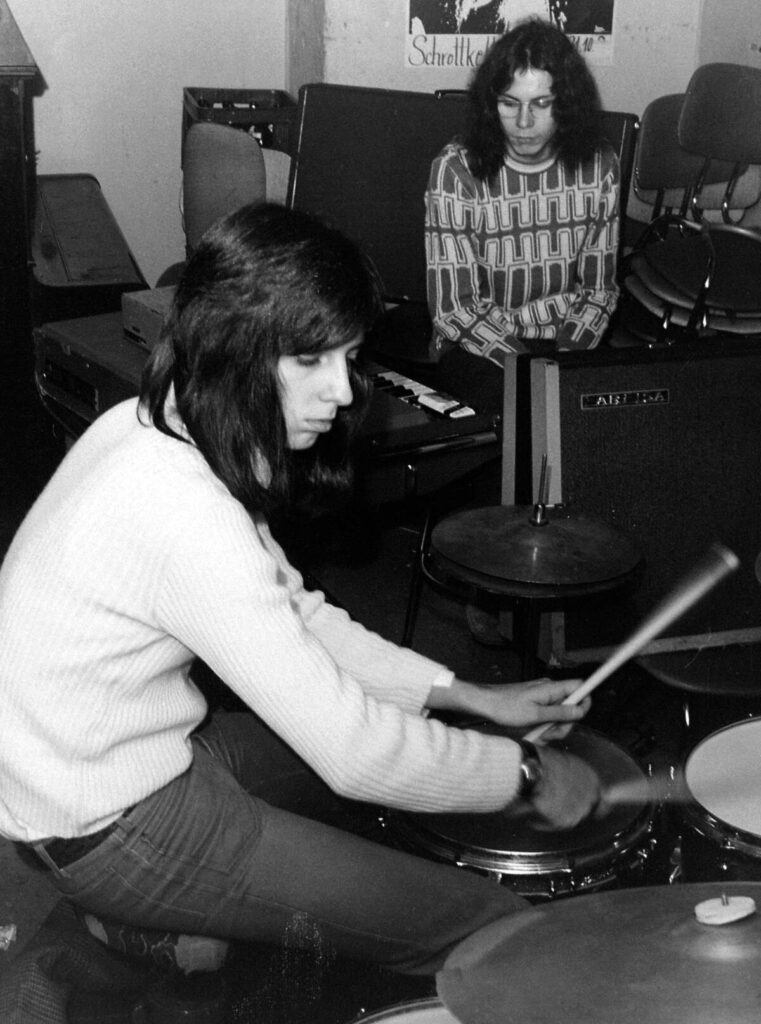

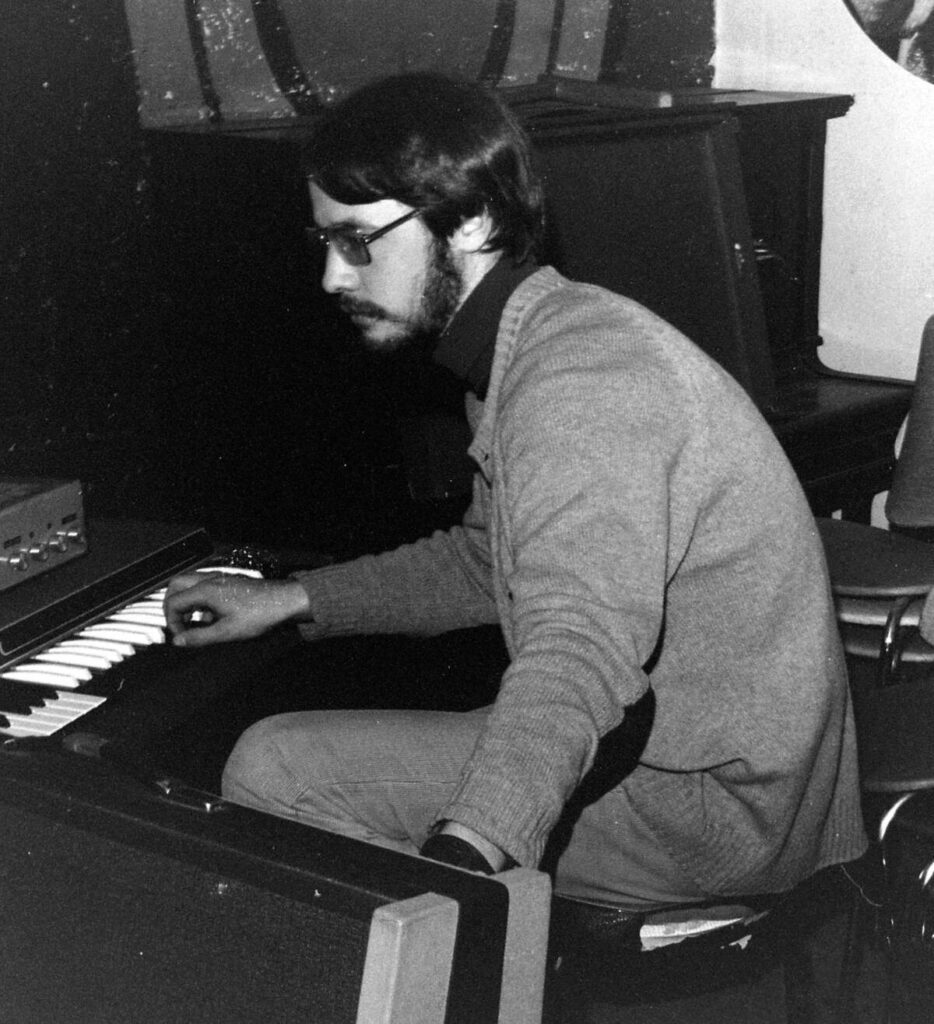

Until 1970, my parents had a hotel in Elverlingsen, about six kilometers from Werdohl. There was only a small workers’ settlement there—maybe 200 people lived there, and almost all of them were employed by Elektromark, the biggest power station in the area. Although it was a small neighborhood, there was a rock band called Fine Art, which still needed a keyboard player (back then, called an organ player). So, I bought a second-hand organ (a Farfisa Compact) with the money I’d earned setting up skittles—our hotel also had a skittle alley—and joined them. When we moved directly to Werdohl in 1971, where my father took over a restaurant, this group had just disbanded. I often hung out in the Schrottkeller, where various groups rehearsed. One group, with our later keyboardist Dieter Kumpakischkis, was called Nostradamus, and they were looking for a drummer. I couldn’t do much on the drums, but I was probably better than the other applicants, so I got in. But Nostradamus didn’t get beyond the rehearsal room.

I wanted to form my own group. I was in grammar school at the time, and apart from me, there was only one long-haired guy (Fred Teske) around. So I hit him up: “Can you play an instrument?” – “Jo, guitar.” Me: “Okay, let’s form a group.” Dieter Kumpakischkis from Nostradamus was recruited, and Karl-Heinz Hamann, who had once helped out with Fine Art, joined as bassist. Tibet was founded.

The band Tibet emerged in the quiet town of Werdohl in the Sauerland. How did the calm atmosphere of your hometown shape the music and philosophy of Tibet?

I don’t think it had any influence at all. Each of us lived in our own world, and at the time, we were focused on England. I regularly bought the New Musical Express back then, which I usually read during school lessons. That way, I was always up to date with what was happening musically around the world, though I didn’t get much from school.

You guys formed in 1971 but didn’t release your first single until 1976 and your LP until 1979. What were the main challenges and influences during those formative years?

The fact that we recorded the 7” single and then the LP so late was simply because we didn’t have the money for the studio. The LP was therefore recorded in several stages, from 1976 to 1979, whenever there was money left over.

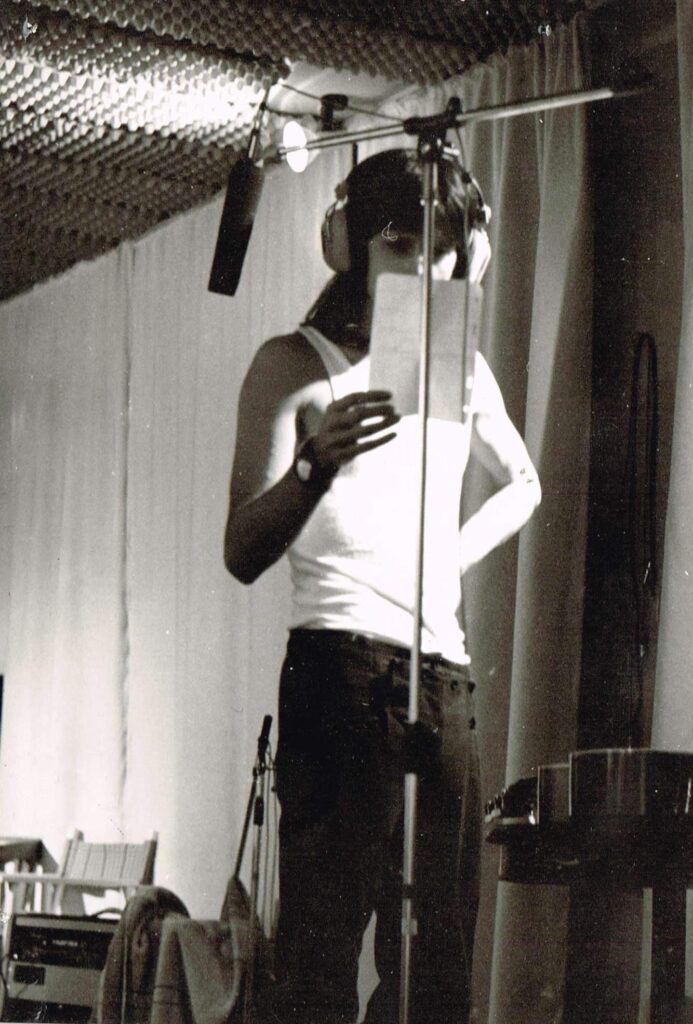

Your performance on July 13th, 1975, at the Goethe open-air stage in Barkhausen was recorded and has recently been remastered. What was the situation like on that day, and how do you feel the live performance differs from your studio recordings?

We were totally exhausted before the gig. We hadn’t slept the whole night before, and now we were supposed to be the last band to play at a time when the festival was supposed to be over (according to the public order office).

Some of our instruments hadn’t been fully functional the day before, and the guitar was constantly out of tune because the equipment had been lying in the damp lorry overnight. So, we had definitely experienced better concerts.

The remastered recording of the live performance is appreciated for its flawless sound. Can you share any specific memories or anecdotes about the recording session or the remastering process with Eroc?

Eroc lives less than twenty kilometers away from us, and he had already mastered three CDs for me. After Tibet, I started a solo project with my partner under the name Cinema. The music is reminiscent of Tangerine Dream, Mike Oldfield, or Alan Parsons. Eroc is also in demand from well-known artists and record companies all over the world. He first smelled the tapes to see if they were still reasonably suitable—I don’t know if he was joking, but he certainly made a serious impression. Teppich had dropped a drumstick at the concert, and Eroc then added three missing snare beats for him. We just told him which squeaks to remove, and he took them out. He also persuaded us not to smooth everything out, as we wanted to retain a bit of authenticity.

How did you define your sound, and which bands or artists were your major influences during that era?

In the beginning, we were all influenced by the Beatles and the Stones, but there’s none of that in our music. It was only when groups like Pink Floyd, Genesis, Yes, and Supertramp came along that you could see that as a musical influence.

It’s fascinating that only one track from the live performance, ‘Fight Back,’ appears on the Tibet studio LP. Can you discuss the reasons behind this and whether there are any particular details or stories related to the other tracks?

When the new keyboard player joined us in 1976 and the singer in 1977, they also brought finished tracks with them, or we created new ones together—that’s how it turned out. We have kept the others until today and want to include them on the next album.

What kind of locations did you play early on? What are some of the bands you shared stages with?

We’ve played everything from the smallest pubs to big halls like the Niedersachsenhalle in Hanover or the Philipshalle in Düsseldorf. We’ve also played small festivals and big ones in England (see LP/CD booklet). We played with Eloy, Kraan, Jane, Grobschnitt, Franz K., Kin Ping Meh, Guru Guru, Atlantis, Grönemeyer, the Scorpions (we had better reviews than the Scorpions), Beggar’s Opera, Chicken Shack, and in England with the Baker Gurvitz Army, Traffic, Gong, Hawkwind, East of Eden, etc. (see booklet).

How did you get signed by Bellaphon to record your debut album?

Jürgen Wigginghaus (founder and then editor of the music magazine Metal Hammer), our later manager, had contacts with editors of another music magazine, who in turn founded a label (Hot Stuff Records), which was distributed by Bellaphon.

Can you delve into the creative process behind this album? What were the inspirations and influences that shaped your sound?

It must have been the influences of Pink Floyd and the groups mentioned above, but the recordings took place in three stages, from 1976 to 1979. There must have been some changes in the influences. In any case, none of it was deliberate.

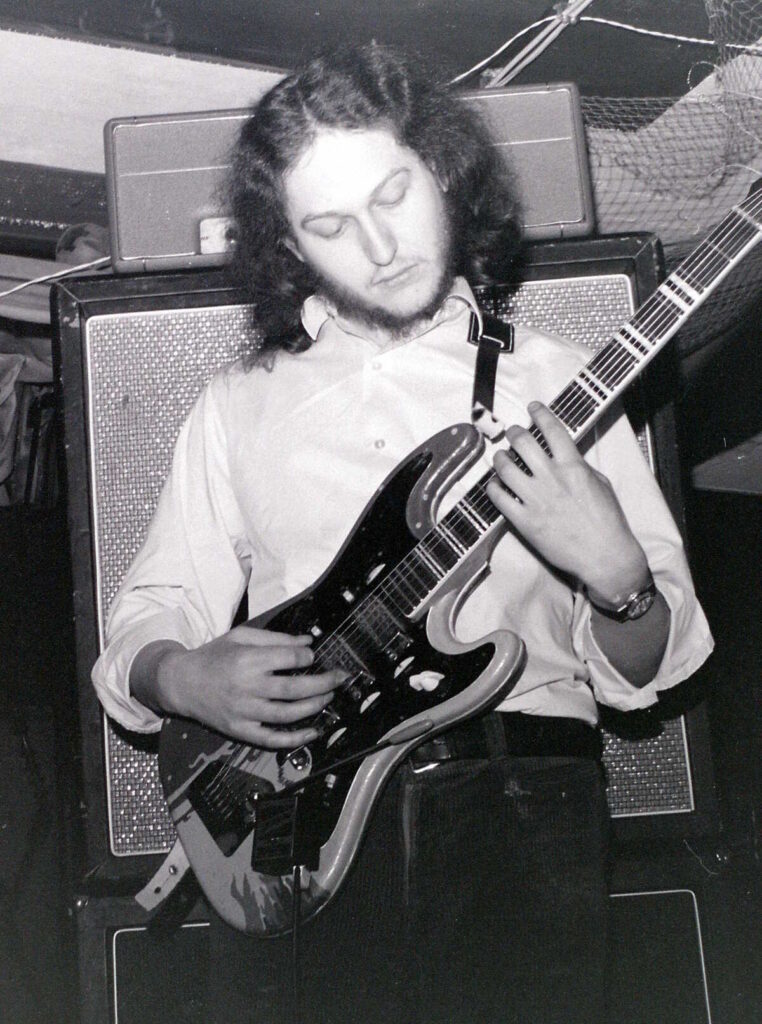

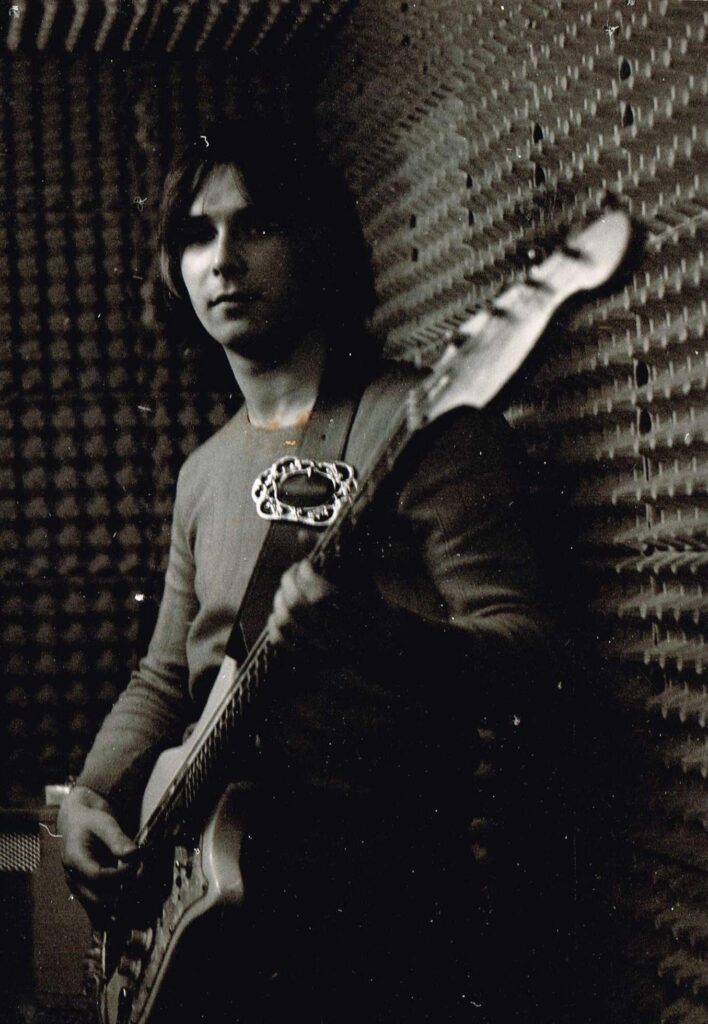

Tell us about the instruments, gear, effects, etc., you had in the band.

Ludwig drums, Fender Stratocaster, Rickenbacker 4003 bass, Roland SH-1000 synthesizer, Vox Jaguar organ, Crumar Compac piano, Fender Rhodes 88, Orange amps, speakers, and mixer. Later, when the second keyboard player joined: Hammond B3, Farfisa Strings, ARP Odyssey, Clavinet D6, Leslie Cabinet.

Would you say it’s a concept album?

No, it was a colorful mix.

Is there a story behind your band’s name?

In the beginning, we also used sitar, snake charmer flutes, and tablas, and the music sounded very exotic. We were simply looking for a name with an East Asian flavor. It was only later that we also thought about the political meaning. We then agreed that we should change the name if we couldn’t make a political statement with it, but everyone we asked in the business advised us not to. Once a name is (relatively) well-known, it shouldn’t be changed.

What are some of the most memorable gigs you played?

That was our strange first gig (see booklet), then the LP launch in Hamburg’s Star-Club, where Beatles friend Horst Fascher and Peter Rüchel from Rockpalast TV were among the audience. And above all, the Watchfield Festival in England (see booklet), where we played with internationally renowned groups. The schedule was very tight, and there were no encores. We were the only group allowed to play two encores that evening. Even the extraneous roadies applauded, and on a rating scale of 1 to 10, we got the highest score of 10.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

This was the third tour in England (with the Watchfield Festival). In our twin town, Derwentside, people were so crazy that we were led to the stage through a basement corridor because there was no other way through. When the fans tried to get into the dressing room, our bass player got trapped behind the door, and we lost him for a while. Our drummer had to sign an autograph on the Queen’s picture in between.

What occupied your life later on? Are you still in touch with other members? Is any member still involved with music?

Yes, we all still have contact with each other – some more, some less. The bassist lives in seclusion on the North Sea, mixer and road manager Peter Halbsgut was head lighting technician at the Frankfurt Opera after his time with Tibet, later opened a bed & breakfast in South Africa with his wife, and now lives near Munich. The lightshow man is an architect in Mannheim. The singer is a chief physician near Mannheim. Keyboardist Deff Ballin joined Geier Sturzflug after the end of Tibet, who had a big hit in Germany (“Bruttosozialprodukt”), and then he was a member of the orchestra for the musical Starlight Express. Fred Teske lives in Wetter (30 kilometers from Werdohl) and is currently preparing the backing tracks for the new album. Although he is a drummer, he has recorded all the keyboard parts (which will, of course, be completed by the keyboard players later). Dieter Kumpakischkis and I still live in Werdohl. I compose and produce for Cinema on the side and also work as a painter. Some of my pictures have already been shown digitally in Los Angeles, New York, Miami, Amsterdam, Venice, etc. If you’re interested: www.poengse.de.

Is there any unreleased material by Tibet or related projects?

Yes, there is enough material for at least two albums, and we are currently working on one.

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Sometimes we think that we could have achieved a lot more. On our last tour in England, after a concert in Bedford, a guy approached us who turned out to be a kind of headhunter. He wanted to introduce us to his boss, a well-known producer. We later found out that this producer was Mickie Most, who had signed The Animals, Yardbirds, Jimmy Page, and Jeff Beck, among others. He wanted to offer us a contract, on condition that we all moved to London. Why didn’t we take him up on it? I think the risk was just too great for us in the end. Not everyone who is promised a great career actually makes it. When the LP came out, manager Jürgen Wigginghaus had planned a tour through Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, but that’s exactly when the band fell apart. We were just too exhausted…

Klemen Breznikar

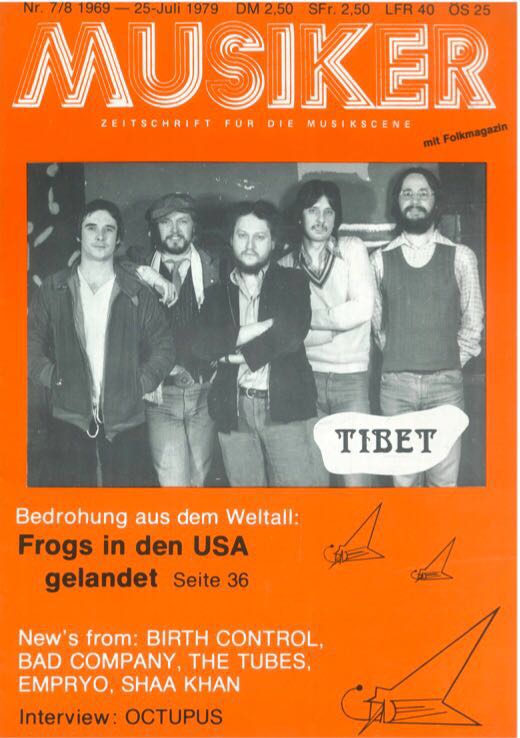

Headline photo: Tibet (1975) | Rest stop on the highway (possibly on the way to the Porta Westfalica Festival) | (L to R): Jürgen Krutzsch, Karl-Heinz Hamann, Peter Halbsgut (Mixer/Roadie), Dieter Kumpakischkies

Garden of Delights Official Website