The Intima | Interview | The Reissue of ‘peril and panic’

The Intima, a boundary-blurring postpunk act that thrived from 1999 to 2004 and shared stages with icons like The Rapture and The Mekons, is finally seeing their 2003 album ‘peril and panic’ get the reissue it deserves—fully remixed, remastered, and released by Post Present Medium.

Born out of Olympia and Portland, the band carved out a sound that was jagged, urgent, and melodic, packing each song with the kind of energy that only a band living on the edge could muster. The album captured the chaos and intensity of the early 2000s, recorded amid a relentless touring schedule during the tense post-9/11 era. Known for their unhinged live shows—think illegal street gigs and amps literally catching fire—the band’s sound was gritty and unapologetically fierce. Now, ‘peril and panic’ returns with all the rawness and power of the original, but this time polished with the clarity they couldn’t achieve back then. The ideas that drove them back then—anti-globalization, fighting the machine—well, look around, nothing’s changed. If anything, we’re all living in the world they were already raging about.

“My hope is that this music speaks to the zeitgeist of today, whereas back in the day, we were like the proverbial canaries in the coal mine.”

Your album ‘peril and panic’ was recently re-released with a fresh mix and remaster. What do you hope to achieve with this updated version?

Themba Lewis: This is a project we’ve had on our minds for a long time. We put a huge amount of work into writing the record, and the initial recording and mastering left it feeling unfinished, like it never had the release we wanted. We’ve all been busy with other things for a while, and the timing was never right to give it the attention it deserved. We didn’t even know if we would be able to locate the original recordings, let alone access and organize the tracks and use new technology to address problems created 20 years ago.

When we started talking about this, we just wanted to see if we could bring it up to a quality level that made us feel satisfied – and there were real doubts about that. It was only once we got into it that we started discussing actually re-releasing it, with the hope that people might relate to it now as much, if not more, than when it was first released. When Dean at Post Present Medium agreed to do the vinyl and digital release, we were thrilled. Not only are we working with a friend, but we’re also returning to PPM, where we released our first 7”, the first release on the label.

Andrew Neerman: This reissue was catalyzed a few years ago when I stumbled upon the album on Spotify, not knowing that it was even streaming there, while I was doing some work for my label, Beacon Sound. I don’t use any streaming services myself, so I probably would never have known it was on Spotify were it not for the label. I hadn’t listened to the album for many years, so it was almost like listening to something for the first time, and I was surprised by how much better the digital version sounded than the vinyl pressing, which, to my mind, was the album (even though there was a CD edition, in 2003 there was no “digital download” or anything like that associated with every album).

I also found myself thinking that the songs had stood the test of time and still sounded surprisingly interesting and fresh 20 years later – not just the music itself, but also the lyrics that I’d written in my early 30s. We then went down the rabbit hole of finding the original tracks, which were sadly recorded digitally, and then asked our old friend and audio engineer Jason Powers to help us re-mix the album from the ground up. Jason, who deserves an outsized amount of credit for this reissue, had engineered several of our recordings in the early 2000s and had also toured with us. The whole process took around 18 months. My hope is that this music speaks to the zeitgeist of today, whereas back in the day, we were like the proverbial canaries in the coal mine.

You’ve always had this ability to blend intense energy with intricate details. How do you navigate the tension between chaotic spontaneity and meticulous craftsmanship in your music?

Andrew: This is a hard question to answer because, for the most part, these songs are highly structured, with moments of improvisation here and there. We spent untold hours composing this music, frequently working collectively and then knitting the parts together as we went. I believe that only Nora had received extensive formal musical instruction. It was only recently, for example, that we realized we were writing in the key of C for no other reason than I had unknowingly tuned my guitar to an odd alternate C tuning. I’m still playing by ear to this day, so there’s an interesting mix of knowledge and intuition happening in these songs.

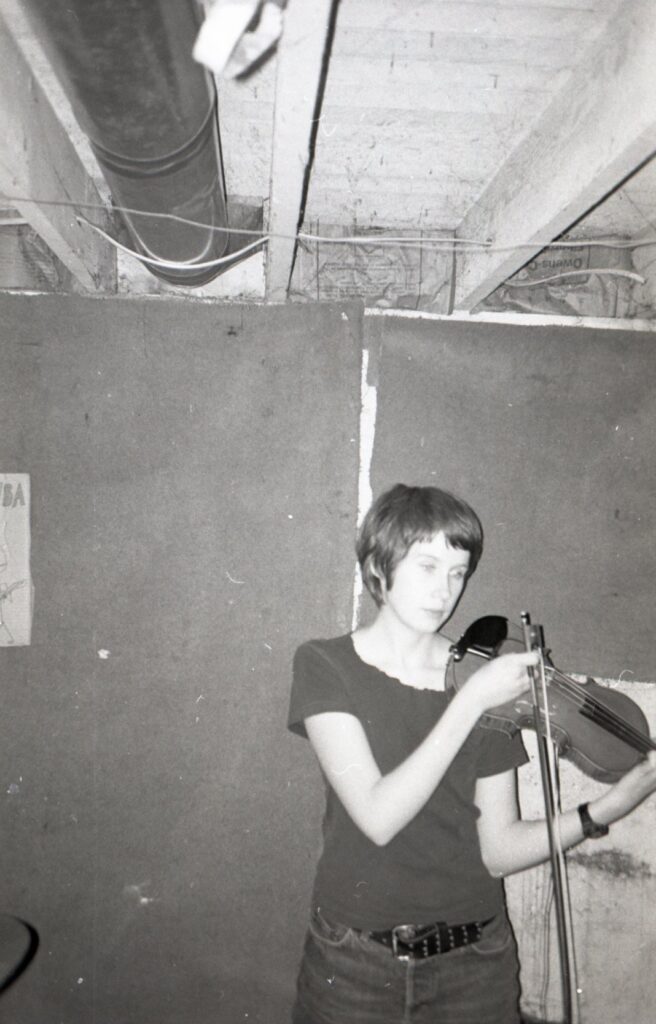

The violin is such a unique and defining element in your sound. How does it shape the overall character of your music compared to more traditional rock instrumentation?

Themba: We started playing music in a sea of uniform instrumentation. It was really just the outlier bands that weren’t made up exclusively of the three predictable instruments: guitar, bass, and drums. There were bands out there doing other things, but mostly bands from other places or outside the punk scene. There were a few examples of strings making their way in, like the Rachels, and violin was what Nora played, so we went for it. There wasn’t a conversation where we decided we wanted a violin; it was more about what we could each bring – and Nora brought the violin. It’s really dramatic – an instrument that can shift the whole energy quickly. In The Intima, it’s been particularly helpful in creating tension and release; it’s basically percussive at points and at others carrying the melody. That’s been fun to play with.

Given the turbulent times during which the original ‘peril and panic’ was released, and the world’s current state, do you find that the themes of the album resonate differently now than they did back in 2003?

Themba: If anything, the themes are more present. Climate and capitalist-nationalism were certainly concerns 20 years ago, but now we actually hear the term “fascism” in the mainstream debate about U.S. and global politics, and we’re watching islands sink and forests die. The warning signs have been there for years, and back when we started, we were sidelined as a “political” band, engaging the real world around us rather than the more mundane themes in more “accessible” (read: radio-friendly) music.

Andrew: What felt like an underground clarion call at the turn of the century (concerns around ecology, egalitarianism, capitalism, war, etc.) now seems like something on everyone’s lips. People used to refer to my brother and me (Alex is the drummer) as the “gloom and doom brothers,” and I have to say we’ve felt a sense of vindication. I’ve been on a lifelong exploration of why things are the way they are, which began when I discovered a writer named Noam Chomsky in Utne Reader as a young teenager after rebelling against the various oppressive institutions I’d moved through as a child (particularly Catholic school). From there, I’ve just never stopped digging deeper, recently studying contemporary literature on the development of patriarchal social relations and their origins (I highly recommend The Patriarchs by Angela Saini). I’m 20 years farther down the path today, so it feels natural thematically to pick up the baton of The Intima and see where it leads.

“We were always a live band”

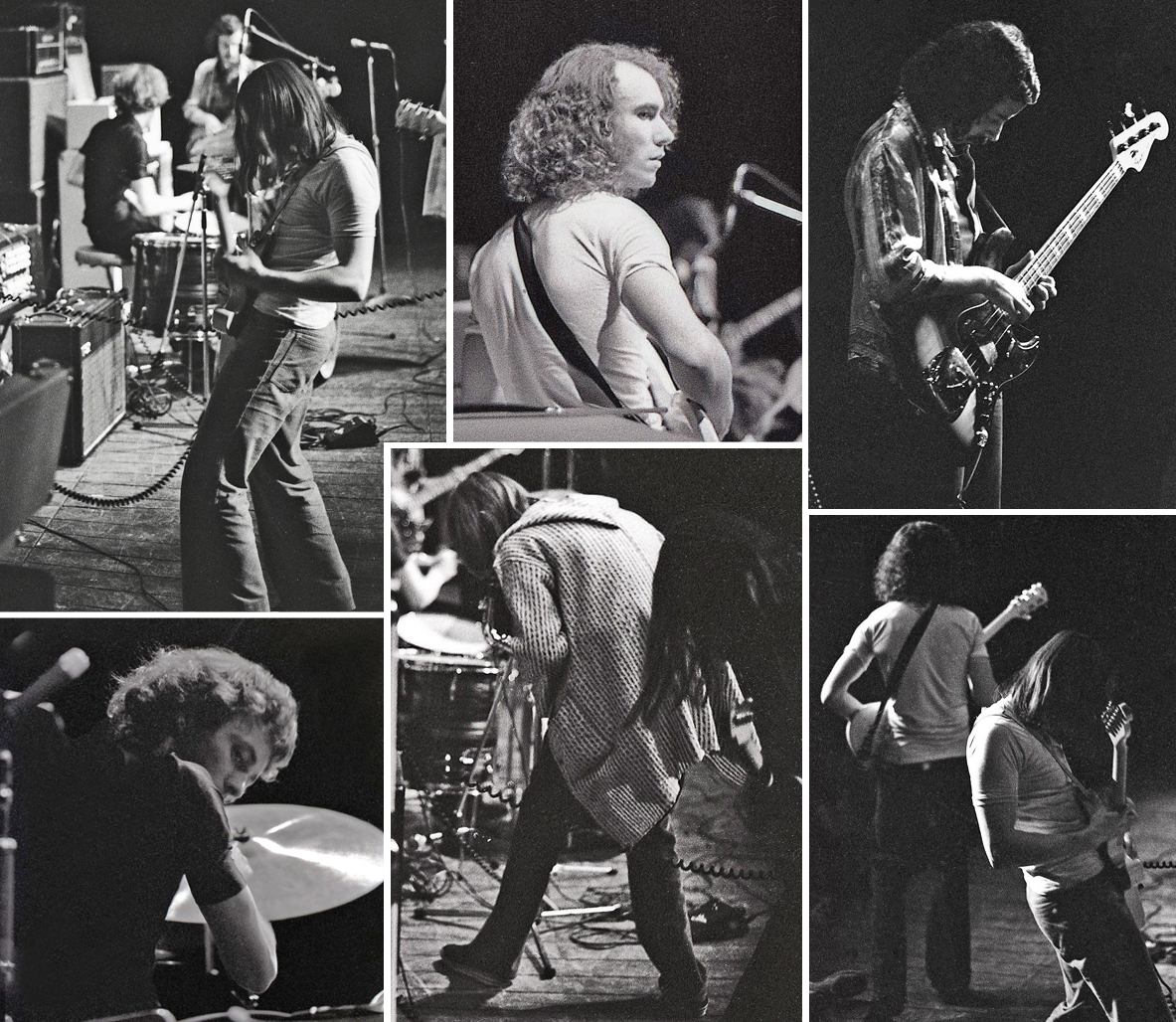

How has the experience of touring and performing live influenced your approach to recording and composing music in the studio? Can you give an example of a particularly memorable live moment that impacted your creative process?

Themba: We were always a live band. I think we generally struggled to capture that live energy in our recordings, and at one point, we tried to rectify that by releasing a live EP on Yo-Yo Recordings in Olympia. Now, I think we’ve shifted to seeing the possibilities in production, and the re-issue of ‘peril and panic’ starts to make use of that learning. Technology has advanced too, and I think we are more aware of space, time, and energy than perhaps we were in the past. Moving forward, I expect we’ll be crafting songs more consciously and then trying to recreate them live, rather than capturing a live experience in a studio. I can’t think of any particular live experience that has influenced this, but maybe just what we’ve learned about tempo and sonic quality.

Andrew: I’m completely in alignment with Themba here. I’m excited to explore different ways of approaching writing music if and when we get to that point. We were already on that track when we released ‘peril and panic’ in 2003, epitomized by the more spacious final song on the album, ‘Trouble Right Away,’ which I think was the last song we wrote before going dormant.

I was reading an interview recently with one of the members of the band Idles where he discussed how production can be “involved in the songwriting process,” and I think this approach is potentially appealing, likely because I listen to so much music along those lines. I think there’s ample space for us to experiment with an expanded or more layered sound, bringing in elements like samples or keyboards, or structuring songs more intentionally around the bass and drums versus the treble-heavy sound of ‘peril and panic.’

You’ve shared stages with a diverse range of bands over the years. How have these interactions and collaborations influenced your music?

Themba: Outsider punk bands end up on bills together because they are doing something different, and we have been lucky to co-exist with bands that were (and are) pushing that scene. Doing shows with bands like XBXRX, Erase Errata, Deerhoof, Karate, Xiu Xiu, Mary Timony… these are amazing bands that shaped a lot of the music that was happening – including ours, for sure.

What would be the craziest gig?

Themba: Monkey Mania in Denver, Colorado, has had a few different names over time, but the shows there were always wild. It was a warehouse where there were basically no rules – we played with a band called Armature that, halfway through the set, pulled out a sledgehammer and started smashing absolutely everything in reach. They smashed big holes into the wooden floor. I can’t imagine those guys get asked back anywhere.

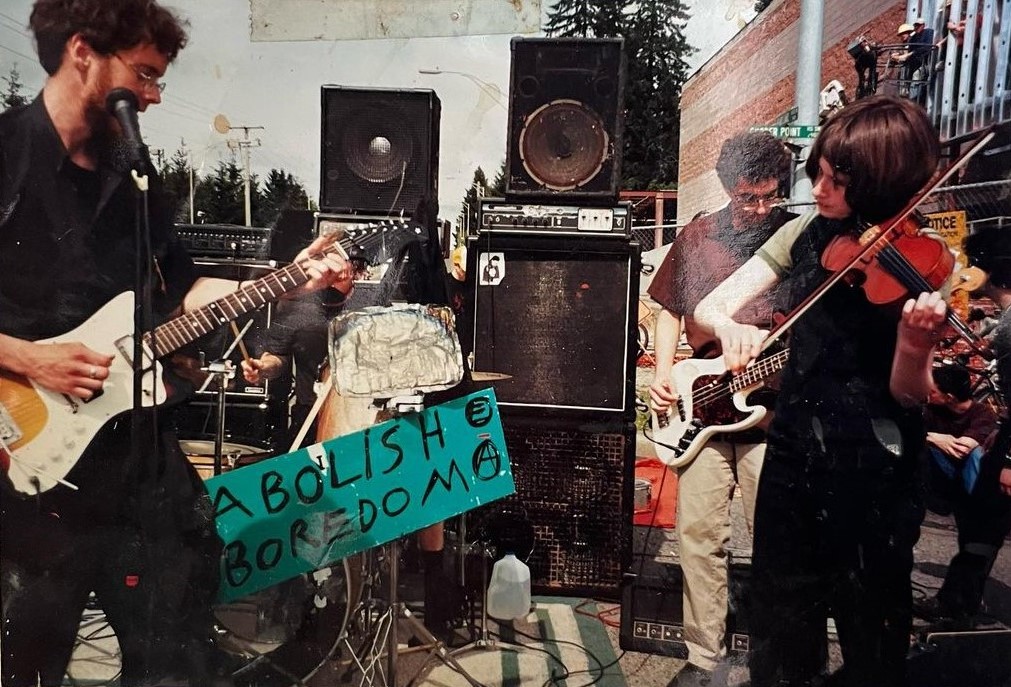

Andrew: For me, probably the Mayday street party we played in Olympia, which was beautifully chaotic. Or the show we played in NYC a few weeks after 9/11. There was also a show in Sacramento with Deerhoof when the PA actually caught fire while we were playing, thus preventing them from headlining (Deerhoof, we’re still sorry!).

Would you like to share about your upbringing? Where did you all grow up? Tell us about daily life back in your teenage years.

Themba: I was born in Swaziland, which is where I got my name. My parents were foreign service people, and I grew up all over the world—a situation of serious privilege but also one that showed me early on how much of the world works. I spent most of my time skateboarding as a teenager in Jakarta, Indonesia. That, and once I moved back to the States, playing music with Alex. But I was living in Nepal and Indonesia and Rwanda for much of that time.

Andrew: Alex and I grew up just outside of DC in Virginia because both of our parents worked in the federal government bureaucracy. Our teenage years aligned with the golden age of indie rock, and we were immersed in groups like Unrest, Throwing Muses, Sonic Youth, the Flying Nun bands, and so much more. Speaking personally, I was a miserable, rebellious teen, and I was lucky to stumble upon Noam Chomsky at a very young age, and by devouring his writing I was also introduced to writers like Edward Said, Howard Zinn, and many others. I’m still following the same thread today. I often think of a defining moment in my life when my mom told me in the Burger King drive-through, while “People Are People” was playing on the radio, that anarchism and peace were “mutually exclusive,” and I remember thinking that I didn’t think that was true but couldn’t yet put it into words. To this day, I can’t bear being in a classroom, which is one of the reasons why I don’t have a college degree.

Was there a certain scene you were part of, maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Themba: Alex and I spent a lot of time going to the old 9:30 Club in DC before it moved, and the Black Cat once it opened. We saw lots of bands there and in the record stores and unitarian church basement—maybe the loudest was Th’ Faith Healers, but really lots of DC bands like Jawbox, Unrest, Slant 6. DC is a tour stop, though, so I remember seeing Radiohead for five dollars, Cat Power when Steve Shelley was still playing with her, Excuse 17… all while I was in high school.

Andrew: The original 9:30 Club in DC absolutely changed my life, but I was too much of a loner to ever be part of any scene at the time.

If we would step into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters, etc. would we find there?

Themba: I spent my high school years in the DC metro area, and my room was in the basement. I had painted lyrics from DC Dischord and Teenbeat bands on some of my walls. I had a giant Mercury Rev poster. I worked at a record store and listened to a lot of different things at the time. Riot Grrrl was a big part of the scene, and I was interested in collective activist things happening—Positive Force, the Beehive Collective, Justice for Janitors, Food Not Bombs.

Andrew: I’m pretty sure that my room, which I shared with Alex (we had it strictly partitioned into two halves), would be everything you’d expect for the era: records, books, a typewriter, art supplies, and band posters. At some point in the mid-80s, I’d discovered K Records—it might have been The Flatmates’ ‘I Could Be In Heaven’ 7”—and I remember putting their iconic logo on the screen of my window using pink glue.

How did The Intima originally get together? What was the main idea behind it?

Themba: The Intima started in Olympia, Washington, on instruments we didn’t really play. It began with Andrew and me, and we quickly pulled Alex in from between his various other projects. We played our first show in 1999. Nora lived in Vancouver, BC, and we knew her through anti-FTAA and WTO organizing. We played a show with her band, the Polaroid Sea, asked her to record with us that weekend, and she was touring with us a few months later. We played in San Francisco, where George and Yvonne Chen offered to do a record for ZUM, and from there, it just kept going.

The only idea around it for me, really, was to create music that was energetic, visceral, and different in a scene that had become increasingly substanceless, even as it launched bands like Sleater-Kinney and the Gossip. I think we wanted to revitalize the revolutionary art and music that had come out of there and contribute to a culture that had always been there.

Andrew: What Themba said, although I’d been playing guitar for about 15 years at that point, only in standard tuning. The first song I ever learned was ‘A Feeling’ by Throwing Muses.

I was deeply involved in planning efforts for the WTO shutdown in 1999 through the Olympia outpost of the Direct Action Network and somehow met Nora during one of her visits. She moved down, and from there, we moved from being a trio to being a quartet, and it snowballed. I was personally feeling inspired at the time by groups like The Ex (especially their work with Tom Cora), Gang of Four, Bikini Kill, etc. I remember seeing Red Monkey at Yoyo-A-Gogo in the spring of 1999 and thinking, “We can do this.”

What followed after you disbanded?

Themba: I kept playing and touring with Tara Jane ONeil, Mirah, and Liarbird. I started sitting in on other people’s recording sessions, which was really different for me, and I had a great time. I got involved with recording the KIT record with Phil Elverum and helping Sara Jaffe (Erase Errata) with a solo record. I spent time recording and playing with Jackie-O Motherfucker too, which was fun—there was so much room to improvise and create new experiences every time we played. But the Bush administration was actively expanding the Iraq/Afghanistan wars, and I felt like I wanted to use my access to engage more directly in countering the narratives that were on the rise all over the world and promote protection work for people being annihilated. I moved to Cairo, got involved with refugee advocacy and human rights law, and have continued living in the Middle East, Europe, Africa, and Asia since that time. I still made music where I could, playing and touring with al Wazza during the Egyptian revolution, and backing up friends when they were on tour, but mostly shifted music to something I did at home at night. I remember hosting a show for Vice Cooler in Cairo, where windows got smashed and the audience was Egyptian art kids and the Ambassador’s family. That was a fun one. I came back to the States two years ago to help out with my parents, and we reconnected, and here we are. Nora (violin) was with me for a lot of that journey, and did some work with the Mountain Goats and the Cairo Complaints Choir as well.

Andrew: I continued working with homeless kids in Portland, a job I initially took to help the workers at the nonprofit I worked for unionize with the IWW. I did that until 2009 or 2010. In 2011, I opened a record store called Beacon Sound because I wanted to get back into music and be more connected to my own creative impulses. Initially, I thought I might find new people to make music with, but instead, I ended up starting a label by releasing an album of my brother’s all-hardware techno under the moniker of Apartment Fox. I closed the record store permanently during the pandemic and focused wholly on the label, which is now up to almost 90 releases. I’m currently part of a small collective space in Portland that houses the label, a bookstore called Lost Avenue, and a record store called Super-Electric.

What currently occupies your life, and what are some future plans?

Andrew: The sole purpose of my life, honestly, is to continue trying to make sense of the world around us and how our species has gotten into the quagmire we are in. Everything else is, in some way or another, an extension of this and an attempt to engage or wrestle with the world we’ve created, which is now in the process of falling apart, or at least changing dramatically. I love to write and am interested in making that more of a formal practice in some way. I’ve also thought about starting a podcast focused on music but from a more philosophical perspective. I’d like to learn how to sail. Lastly, I’m the father of a 9-year-old, and that takes up a lot of my time and energy. I’m also, of course, very curious to see what happens with this second chapter of the band.

In revisiting your past work, do you find yourself reflecting differently on the music and the band’s journey? How has your perspective on the album evolved over the years?

Themba: Absolutely. Our songwriting during the ‘peril and panic’ era was so frenetic and dense that it would quite literally be hard to recreate now. We aren’t the same people we were then; we’ve learned to breathe a bit more.

Andrew: It’s funny because I feel like very much the same person, just (hopefully) more evolved in my thinking. Especially when it comes to nuance and not running from my contradictions, of which there are many—the label being one because anyone involved in the reproduction of music is married to the petrochemical and plastic industries, not to mention server farms. I think my feelings about the album have become softer and more accepting of the intense process of writing, recording, and touring as part of a group with complex internal dynamics (imagine two brothers and a couple in a tour van for six weeks, haha) that made it what it is. I also feel a sense of accomplishment in making something pretty unique in the sense that I can’t think of many other bands, either then or now, who sound much like us.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Andrew: I’ll close with an optimistic quote from the author David Graeber, although I have to admit that I’m not so sure about the “just as easily” part: “The ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently.”

Klemen Breznikar

The Intima Instagram / Bandcamp

Post Present Medium Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / YouTube

Thank you for this wonderful interview! I’m the proud aunt of Themba, and I know Nora, too. I think I met the Neerman brothers when visiting Themba and his family in their Falls Church Days. AND! I am the proud owner of two copies of the new release! Congratulations!