Ray Russell | Interview | “Music is fluid architecture”

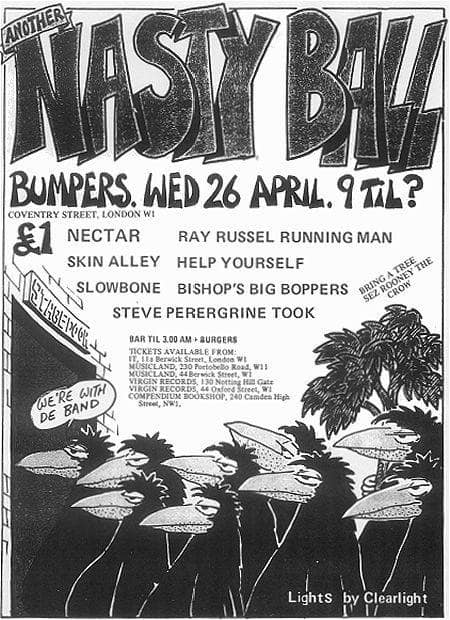

Ray Russell’s illustrious career spans a broad range of projects, from his early jazz days with the John Barry Seven, Graham Bond, and Georgie Fame to the Ray Russell Quartet, Rock Workshop, and progressive rock with bands like The Running Man and Mouse.

Born on April 4, 1947, in Islington, London, Russell began playing with a ukulele before progressing to various guitars. His influences ranged from The Shadows to jazz guitarists, and he first gained public attention at 12 with his band, George Bean and the Runners. At just 15, he joined the John Barry Seven, playing on iconic James Bond soundtracks like Thunderball and You Only Live Twice. Throughout the 1960s, Russell became a sought-after session musician. By 1967, he was playing in the legendary Graham Bond Organisation, touring with The Soft Machine, Jimi Hendrix Experience, The Who, Pink Floyd, and others, while also forming his own band, Rock Workshop.

In the 1980s, Russell’s career flourished with a blend of session work, collaborations, and production. He worked with artists like Gil Evans, Mike Batt, and Heaven 17, contributing his unique guitar sounds to projects like Tina Turner’s ‘Let’s Stay Together.’ He also formed the trio RMS with Mo Foster and Simon Phillips, producing the album ‘Centennial Park’ and continuing to influence the synth-pop and jazz fusion scenes. By the decade’s end, he composed music for TV series such as Bergerac and Inspector Alleyn Mysteries.

In the 2000s, Russell transitioned to music production for television, composing scores for series such as A Touch of Frost, The Quest, and Diamond Geezer. His work earned him the Royal Television Society’s Best Music Award in 2006. In recent years, he has remained incredibly busy, producing a wide array of projects and recordings.

“You can form a physiological relationship with the musicians.”

Where did you grow up, and what can you share about your early life? What was it like back then?

Ray Russell: I grew up in North London, Islington to be precise. When I talk to younger people, I always preface the answer by asking them to imagine a time with just 3-channel TV, no mobile phones, and no internet. But there was a music paper called Melody Maker, which gave a lot of info about what was happening with bands and venues. It was more of a trade paper.

School was hell most days. I was overweight and had to fend off bullies who probably became the future villains and policemen. My dad, who played piano (he started in the army), taught me the basics, and I played his accordion and other instruments. But I gravitated to the guitar, as it was a portable instrument with a presence—a presence that still exists.

I have to say we weren’t well off, and buying a guitar was an effort of saving, with my folks putting in the rest. That’s when my life changed. Music became a defense against the school idiots, and I just didn’t stop playing. We had a band called—wait for it—”George Bean and the Runners”. We started to do gigs, playing covers and some instrumentals.

At 16, I left school, the earliest leaving age. I flew out of the gates after being offered conscription into the army. Believe me, people who serve are brave and have my utmost respect, but at that time, all I wanted to do was play. It was lean, but I got a job making up the individual parts to scores for classical concerts. It was interesting—and in fact, it was where I met the late Paul Buckmaster, who I teamed up with years later for the Judy Tzuke album ‘Welcome to the Cruise.’ We were like the first type of Deliveroo! A moped taking boxes of scores to the Festival Hall and other venues, including Abbey Road 1.

I also got another job in a warehouse, which was a benign job that wasted hours moving amps from one side of the warehouse to the other. But it turned out to be the second biggest life-changer.

I was reading Melody Maker, trying not to be found, when I saw an article by Bob Downes, the sax player in the John Barry Seven. They were looking for a new guitar player as Vik Flick was leaving, and Bob put his phone number at the end of the article. Wow! So, of course, I called. He asked me if I could read music (I couldn’t at the time), so I said yes. He asked if I knew the John Barry hits, and I said yes (but “no” would have been more honest). We arranged for me to have an audition the following week at a cinema in North London.

I skipped out of work with a lame excuse, got home, and sold nearly everything I had, except the guitar and little amp, to fund a record player and a copy of John Barry’s ‘Greatest Hits.’ I woodshedded those tunes constantly for a week.

One thing that happened between my leaving school and getting my first job was that I happened to walk into the Burns guitar shop—long gone now—and I met Jim Burns. We got on, and he invited me down to his factory in Essex. I tried the guitars, and he—to my amazement—gave me a Burns Split Sound. This was big time for me, and of course, I played it with the JB7 and on the Bond films.

So, back to the audition. I got to the cinema (by bus), but it was closed. Bob climbed over the ticket kiosk and plugged my amp in. They set up a music stand, and I was terrified. The first piece said ‘The James Bond Theme.’ I played it note perfect, and they were impressed. I played half of another tune, and they said that was enough. Bob said, “Hey, this guy’s good.” Then he climbed back over the kiosk and had to dial out to speak to John. After the call, he said, “Are you free next week?” I said yes, and they gave me a lift back home. I exclaimed that I was going on tour at 19 with people my folks had never met. Luckily, they were all ten years older than me and were very kind, helping me enter this strange world of touring. I was now a pro musician!

Was there a particular scene you were a part of in those days? Did you have favorite hangout spots, and did you attend many concerts back then?

Not so many concerts, but I did go to a club called the 2i’s, which was the place where all the rock guys went. Everyone would jam, so I got a good taste of playing with guys better than myself. This is where I started to see beyond the rock format of the time.

A guy I met at my second job, with whom I stayed friends, would play me West Coast jazz, which was Wes Montgomery, Jimmy Smith, and from there I discovered Blue Note. Improvisation became my aim—to know what was going on and to be able to hear the paths of the other musicians (group creativity). This also led me to Ronnie Scott’s “Old Place” before the “new club,” and I listened to a lot of jazz, all I could afford at the time. I sat in with the Bob Stukey trio as his guitar player was unavailable, and I joined them in between the JB7 gigs, which were now thinning out as John was really a full-time film composer by then. I did eight Bond films with him, and it was fun. Luckily, I had learned to read quite well by then.

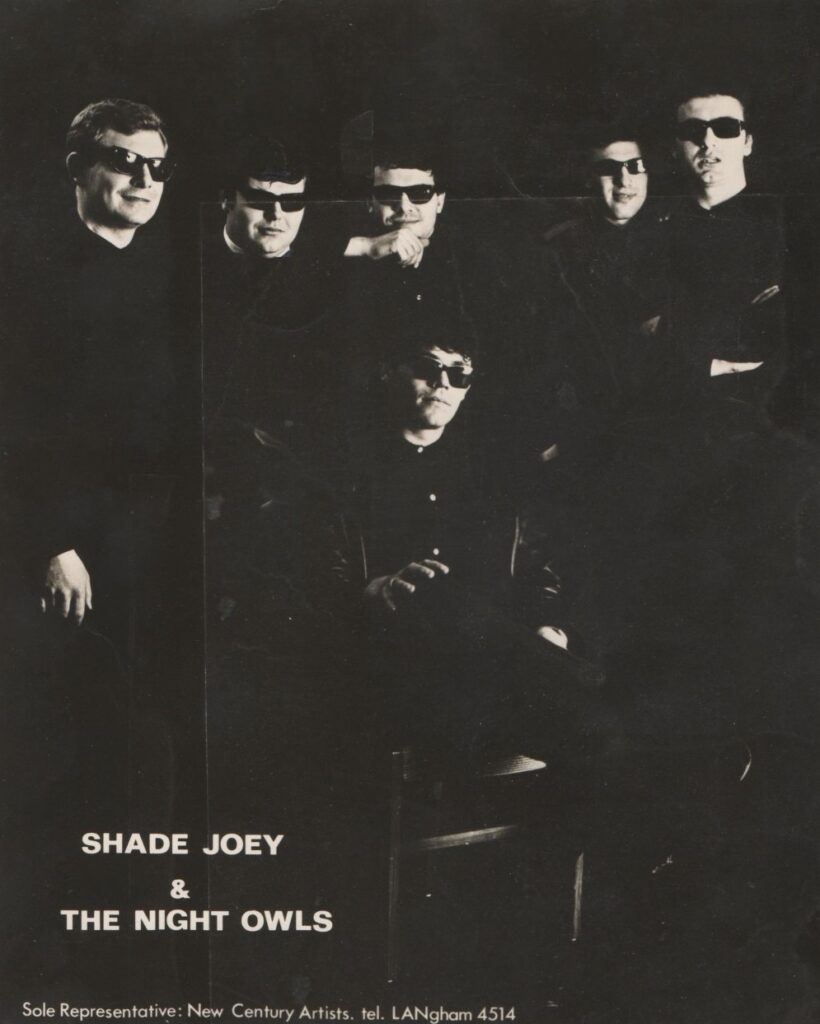

As a footnote here, some of us did a band and made a single with the legendary Joe Meek producing. We were called—wait for it—Shade Joey & The Night Owls! We had a minor hit with ‘Blue Birds Over the Mountain.’ That only lasted a few months. I did some gigs at Scotch of St James. Jimi used to be there, and a lot of famous faces. This became a haunt as well, as I was good friends with Gered Mankowitz, who took some legendary photos of just about everybody who was famous at the time.

What were some of the first bands you were involved with in the 1960s?

I was lucky enough to be on a recording session one day (one of my first ever sessions), and there were three guitar players on it: me, John McLaughlin, and Jimmy Page. We were chatting away during the break, and Jimmy said, “I’m not doing any more sessions, I’m going to form a heavy rock band” (Led Zeppelin, of course). John said, “I’ve been asked to go and try out for Miles Davis.” He was with Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames at the time, and he asked me if I wanted to join them after he left. I said yes, and there I was playing blues and R&B (the original form) with George. We toured endlessly, and I still found time to fit some sessions in and play at Ronnie’s. The touring with Georgie’s band was a distinct contradiction to the Seven. Some very drug-induced nights became bizarre. I didn’t partake.

After Georgie, I joined Graham Bond. This was the most bizarre band ever. He was very strung out on junk, a shame, as he was intelligent and a great player. He could play the Hammond organ like no other. He could play the bass pedals, chords with his left hand, and solo with his alto with his right. When he wasn’t working, by that time I was venturing into John Coltrane and Archie Shepp—very interesting. Graham fell apart at a gig in Bridget Bardot’s villa. He hadn’t paid for the hire van back in the UK, and Interpol were after him—and us by default. He was strung out. The promoter didn’t want to pay us, so Graham dressed up in his magician costume with a copy of a book of spells under his arm and exclaimed he was Aleister Crowley’s grandson and would do black magic on the promoter if he didn’t pay us. The poor guy paid up!

I found Graham the next day in the bathroom with a needle in his arm, asleep. I had to remove the needle and then call an ambulance. He survived. He fled the hospital and used most of our money to fly to London. I never saw him again. We drove the van back after pacifying the hire company. Ouch, but the musical and social experience was a one-off.

Tell us about your introduction to the jazz scene. How did that eventually lead you to the rock bands you became a part of?

I’ve touched on it earlier, but some really good things happened. I was called by David Howells, who was an A&R man for CBS. And what he said, you never hear now:

“I’m getting a jazz label together for CBS of young British jazz talent. Would you like to make an album?”

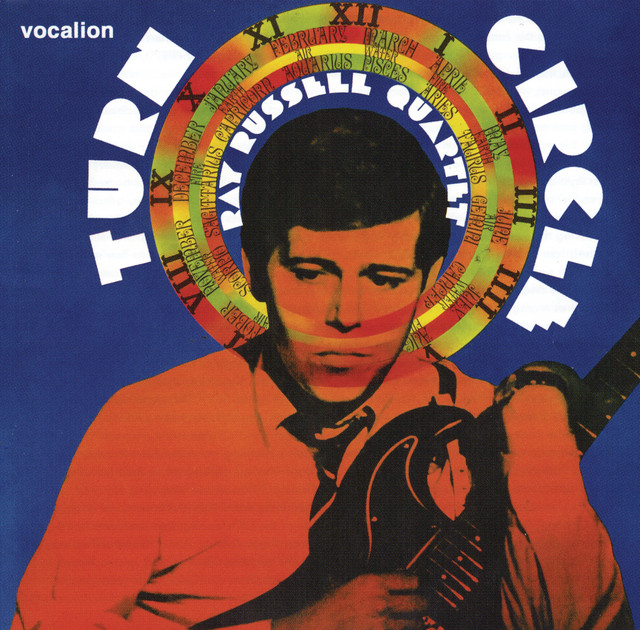

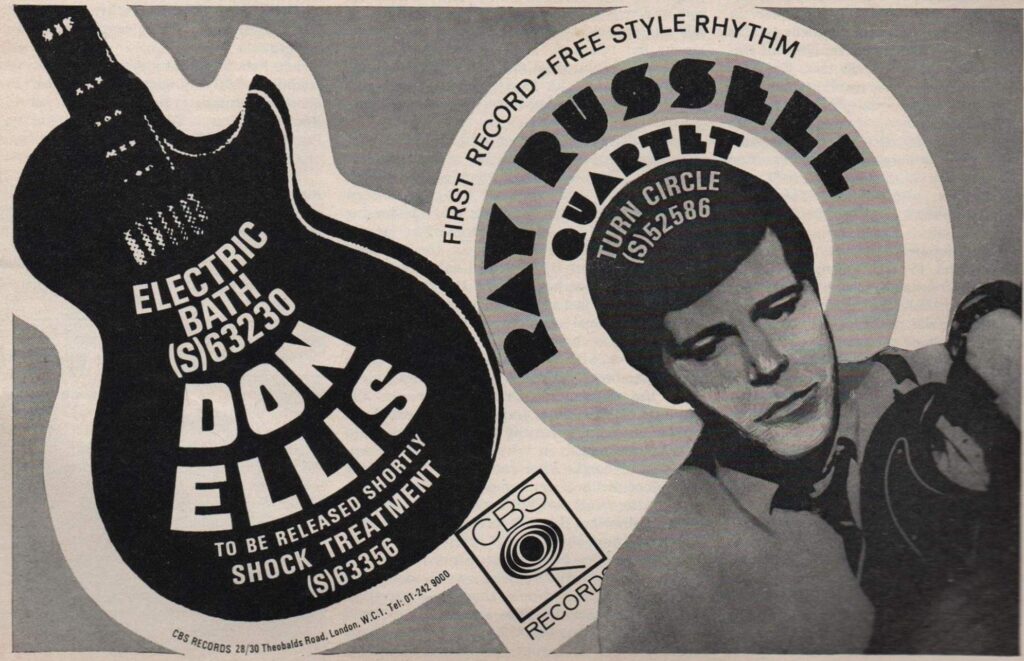

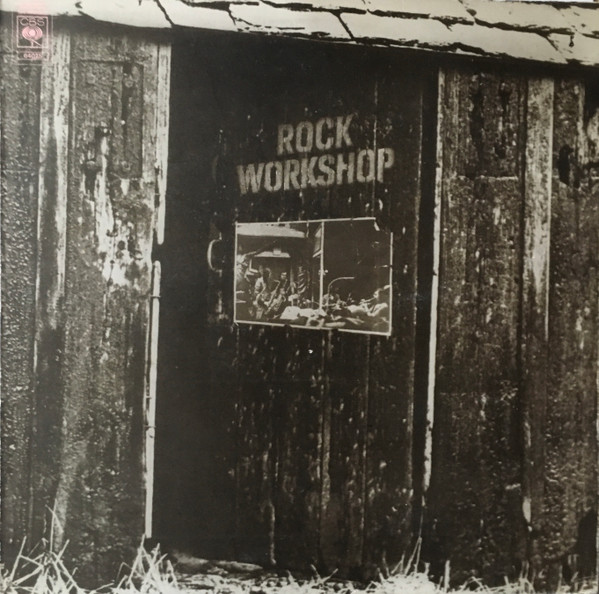

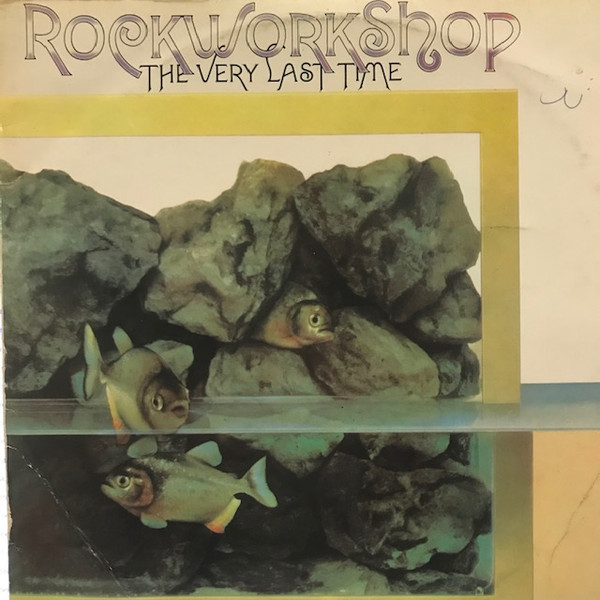

“Yes,” I replied, and ‘Turn Circle,’ my first album, came out, followed by ‘Dragon Hill’ and ‘Rites and Rituals.’ A following started, and I noticed that the audiences were also into the prog scene, which I was listening to. A band called Blood, Sweat & Tears was in the charts, and David Howells was keen to get a UK version together. I’m not sure that what got recorded was exactly what was required, but Rock Workshop was born. Singer Alex Harvey was featured. A ten-piece band with two drummers! I saw this as a chance to fuse together the expressions of jazz, prog, and the role the guitar had to play in the changing world of sonic signatures.

We made two albums and had two minor hits, but we did get a following:

‘Rock Workshop’

‘The Very Last Time’

It gave me the tools that started me becoming serious about composing. I never saw any divide in styles of music; the guitar has nearly always been the common denominator.

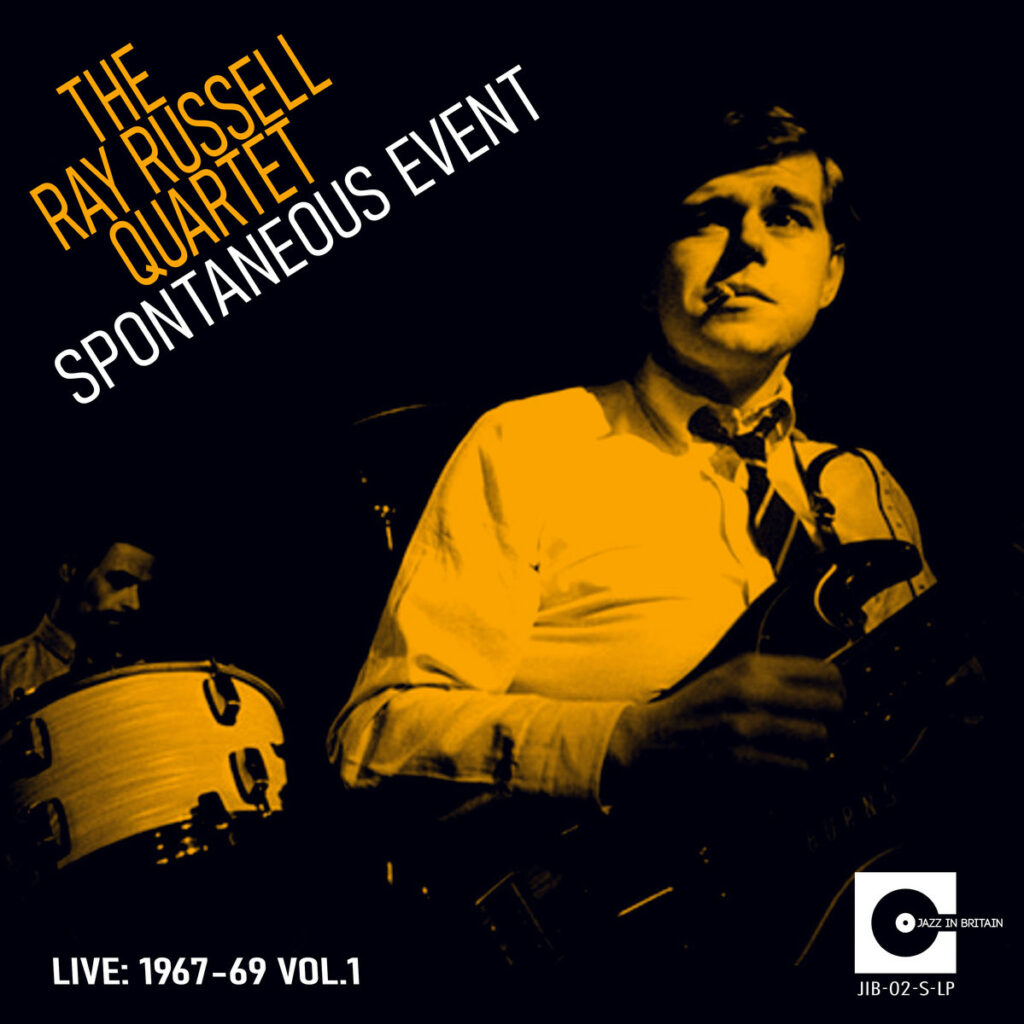

Could you describe the main idea or vision behind your own Quartet?

The first album, ‘Turn Circle,’ was more traditional, and David Howells asked us to include a couple of known tunes, hence Footprints and the Charles Lloyd tune, ‘Sombrero Sam.’ My sound was more traditional, but where we went harmonically was leaning into a more free approach. ‘Dragon Hill.’ We added four brass players for some arrangements, which I tried to make more like Carla Bley would do.

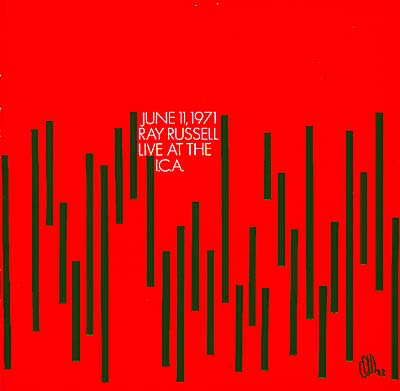

It was a concept album as we had three parts to one tune, which made it filmic in a way: The Day in the Life of a Slave of Lower Egypt. I was into the ancient mythologies, and this was a vehicle for expressing a free approach with a blues thrown in. This was probably the high point of this band. It led to the ‘Live at the ICA’ album later and became a septet. We were recording four-track at the time, and the idea of an overdub didn’t exist then. But 16-track was around the corner, and the new wave of the session musician was starting.

Anyway, back to CBS recordings. The ‘Dragon Hill’ cover, which was a picture of Earth from the Moon, was a popular choice and brought us a lot of fans. It was all about perspective. The music had to be seen as a different approach to the ear. It had to be open music. This was a great way to improve cognitive powers. You can form a physiological relationship with the musicians. Apart from what you hear, you can see by their physical movements how they are feeling the music.

“…trying to escape the bondage of the system”

I’d love for you to explore the concepts, ideas, and compositions behind your fantastic albums like ‘Turn Circle,’ ‘Dragon Hill,’ ‘Rites and Rituals,’ ‘June 11th 1971: Live at the ICA,’ and ‘Secret Asylum.’ Could you shed some light on each of these releases?

So, my time at CBS came to an end when David left. This was the time when another A&R guy, Olaf Wyper, who also painted impressionistic works, wanted to combine one of his paintings with an album. I had applied for a bursary from the Arts Council and had been awarded a small sum to put on a concert at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London.

One of Olaf’s paintings hung there, and that is the one you see as the cover of ‘Live at the ICA.’ This was indeed a live album and probably the most enjoyable live jazz album.

The place was heaving, and I felt inspired by this. Even a few last-minute hitches didn’t change anything— all the guys were on form. This album got re-released on another label with some tracks we didn’t have room to put on (vinyl had 20 minutes per side).

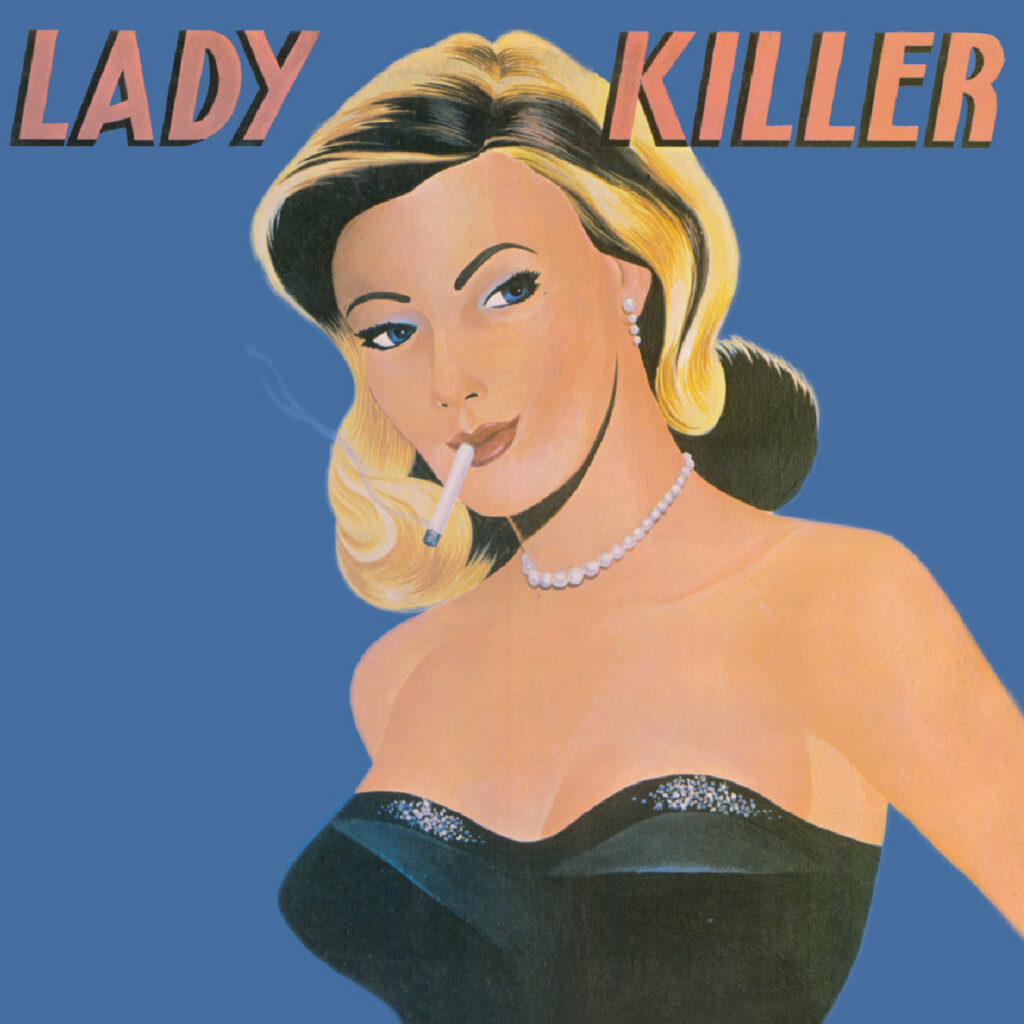

Now, I’m going slightly out of sequence here, but the relationship with RCA and Olaf became a kind of mirror image of CBS in that we started to talk about a prog album. So, the band Mouse was born. I can’t remember why it was called Mouse! We went into Trident Studios to record ‘Lady Killer,’ an amalgam of ideas that was a broad brushstroke. Half of it was just made up in the studio with a kind of environmental inspiration. We just started playing, derived a song format, and recorded. This, of course, was the studio in its grandest form: 24-track, effects, great acoustic space, great and patient engineer. ‘Lady Killer’ has just been re-released for the third time now.

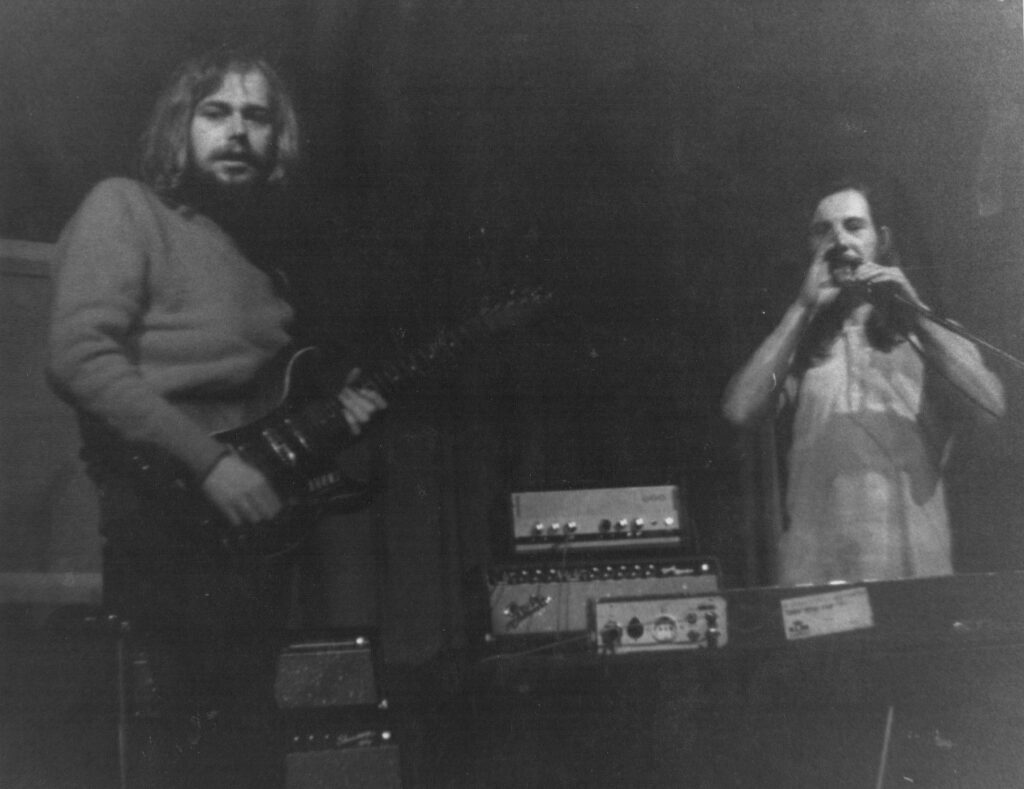

In Japan, the original vinyl sells for a lot of yen. Shame the artist never gets to see any of that dosh. Then, RCA wanted another prog album. This was basically a trio of Compradore: Alan Rushton on drums, Jeff Watts on bass, with some vocals from the late Alan Clare. The Running Man was born. Named after the film, trying to escape the bondage of the system. I remember part of the sleeve note on the ICA album described me as trying to escape from the six-string cage.

I think we all were defying the rubber walls. It was a very anti-album. Someone said, “If you get asked any questions, just say “Fuck you”.” That was funny but totally unworkable. HAAA.

“My spiritual father is Gil Evans”

Who were some of the most influential musicians for you personally? What specific qualities in their playing inspired you?

Through the years, I’ve been lucky enough to play with people I admire and respect. I have a great love for their music because they have the common ground of having a “sonic signature.” You always know it’s them.

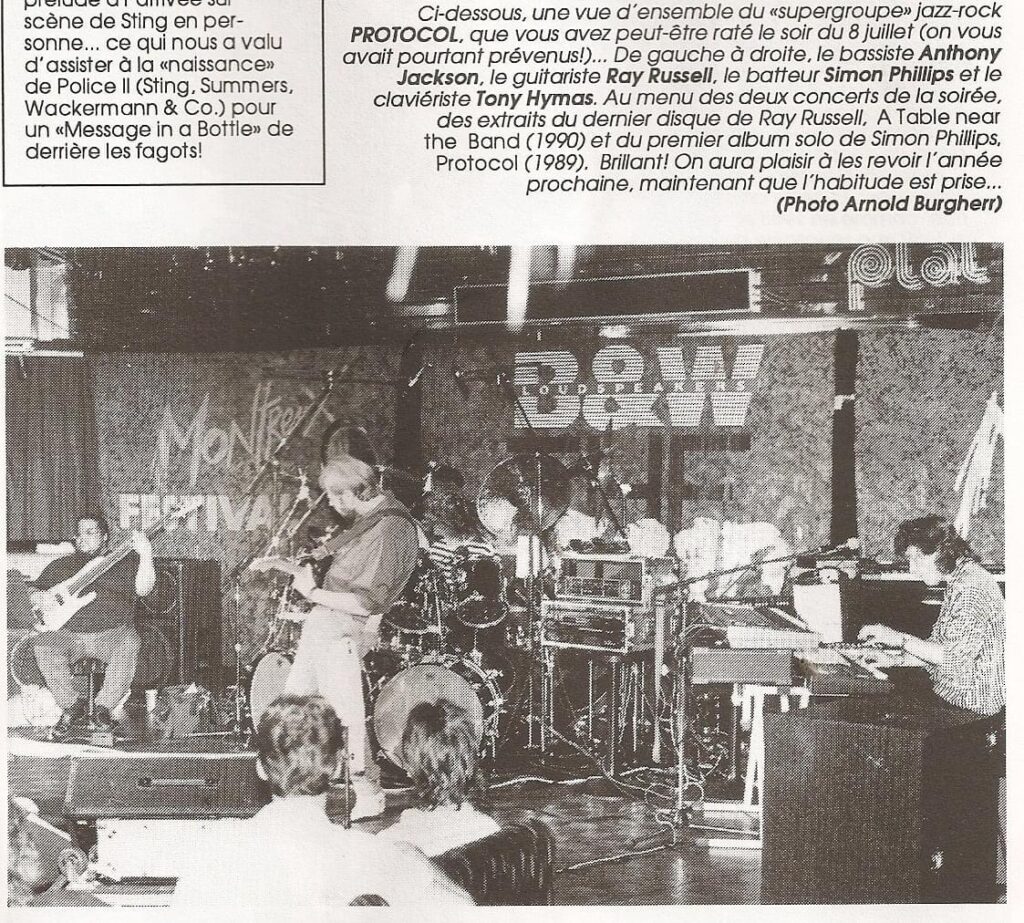

Sometimes it’s the album as a whole that inspires you. I’m sure a lot of people found that with ‘Kind of Blue.’ My spiritual father is Gil Evans. He taught me what was like Zen and the art of listening. Your listening has to equal your playing. He was fabulous. I wanted our gig at the Montreux Jazz Festival to go on forever.

Simon Phillips taught me things about time that I hadn’t considered and were amazing. The band with Simon and Anthony Jackson—another all-time favorite—was a masterclass in cognitive creativity.

The late Mo Foster, a brilliant bass player and personality, transcended any negative situation. He would fight negativity with humor and always win.

Nearly everyone on Blue Note and Impulse.

Tony Roberts—a tenor player that is seriously underrated.

David Torn, Johnny Mac, the late Paul Butterfield, who I jammed with on several occasions.

Gary Husband—just wow!

So many. The late Gary Windo, his solos were like a Dali painting.

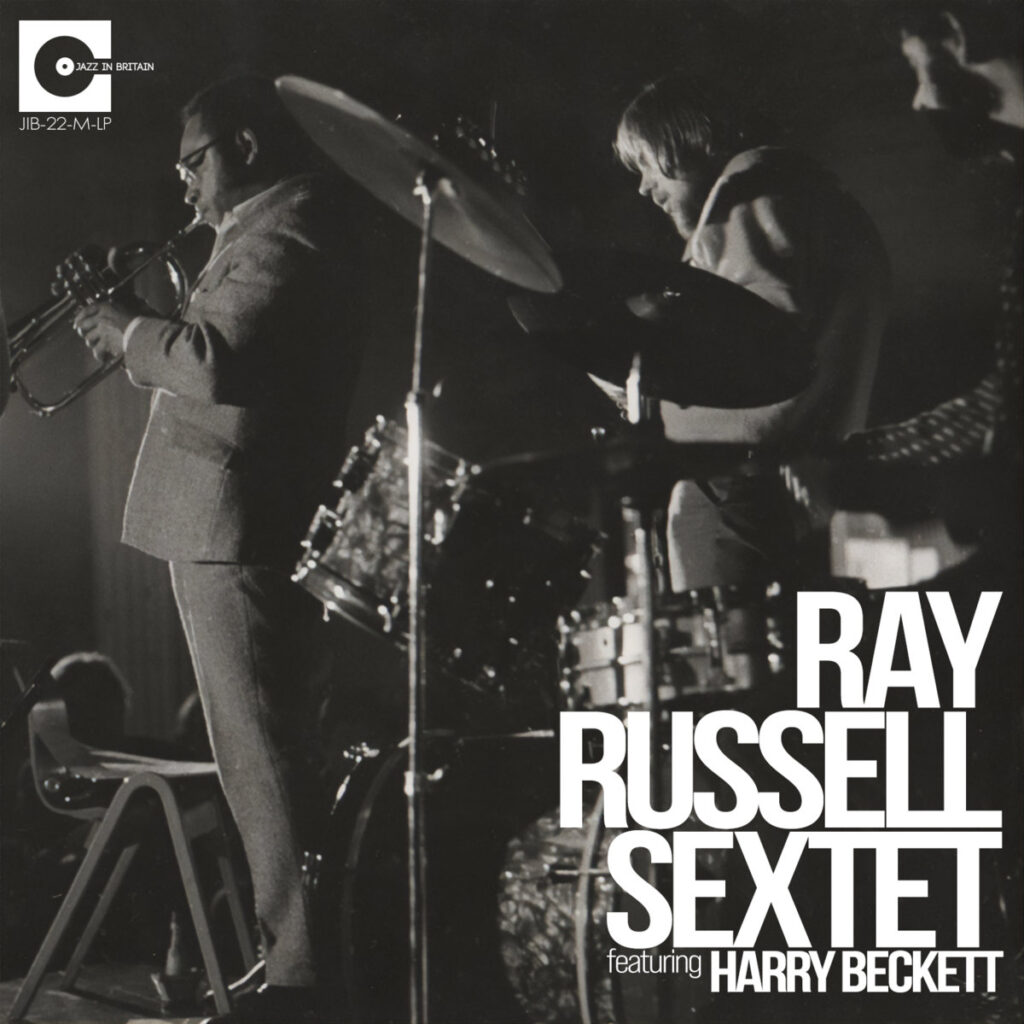

Harry Beckett, the trumpet that smiled.

Jimmy Johnson, the complete bass player—he will fly in all weathers!

So many, I might come back to this.

You released two albums and several singles with Rock Workshop.

Yes, we did quite a few live gigs, but the logistics of moving ten people and their gear were challenging.

How did your experiences with the Quartet compare? Did you perform in the same venues as you did later on with the more rock-oriented bands?

Yes, but in the 70s and part of the 80s, you had an active student union that was booking various bands. They made some great choices, including some obscure acts that were brilliant, like Sun Ra, for instance.

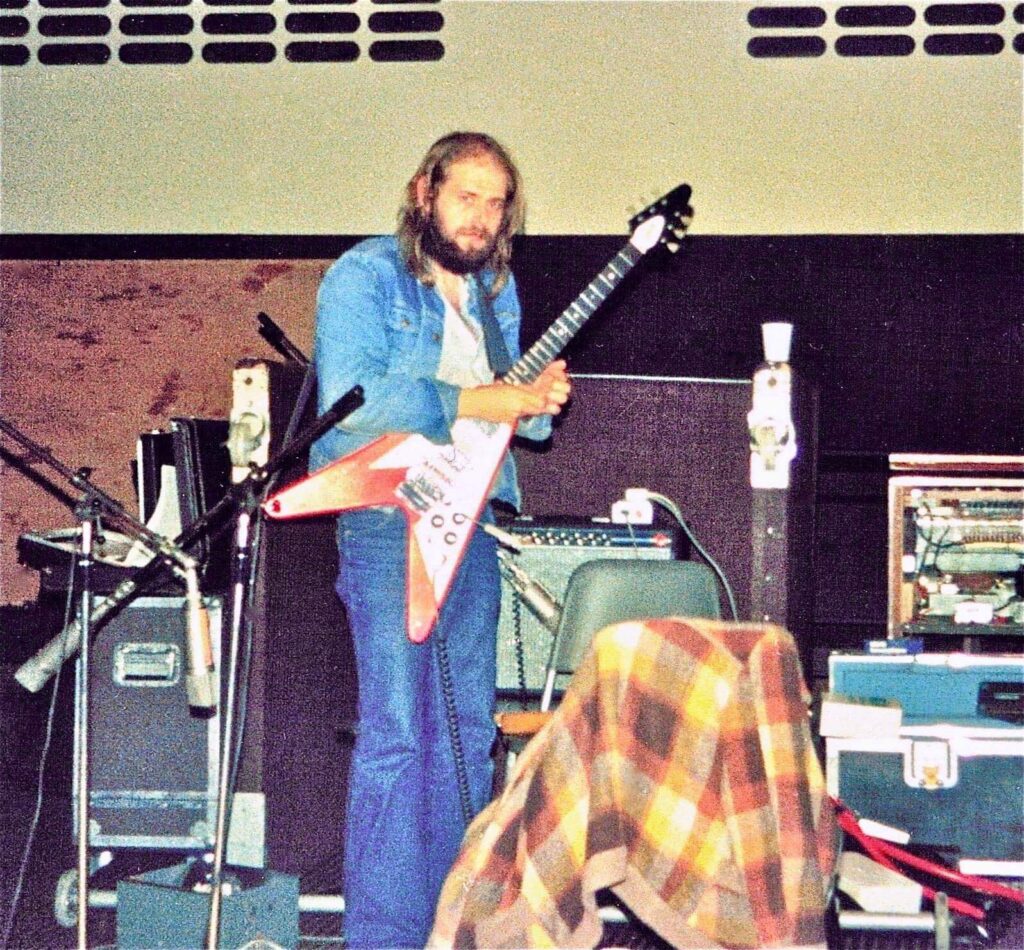

How did The Running Man/Mouse project come about? The 1972 album is widely regarded as a standout. Do you have any particular memories from the recording sessions?

Speaking of ‘Lady Killer,’ Trident was a very dry-sounding studio. I remember working there with Phil Spector and later John Lennon. Both tracks never came out. But we played around with reverb and basically dialed in the size of the hall we wanted. For me, it was hard to filter all the information I wanted to try into a form that made sense. I remember moving some screens because we just couldn’t see each other. When we moved to a studio that is now a block of flats but was called C.T.S. (where a lot of Bond films were recorded), it was special. I had a small string section playing this atonal tune. They were all looking at each other — the expression was, “What the F**K.” But it was one of the first albums where we felt empowered to use the means of expression at hand and also where the mix was equal to the musical creativity.

Did you perform live with The Running Man, or was it mostly a studio-focused project?

We did, yes, not that much, but the gigs were fertile — something always happened that was off the wall.

Was Mouse a continuation of your previous work, or did it emerge as something entirely new?

A continuation, but a more angry album. It could have been called Rubber Walls or Biting the Velvet Glove!

It’s exciting that Guerssen is reissuing your sole Mouse album.

I think they should release The Running Man as a companion album, as it was the second half of the stream of ideas.

You’ve collaborated with so many musicians, including Bill Fay, The Sensational Alex Harvey Band, and Jonesy, among others. How did those collaborations come about? Did you choose where to collaborate, or were you often invited to join by others?

Bill Fay, he is the most underrated songwriter of all time. I can’t begin to tell you what those sessions on ‘Time of the Last Persecution’ meant to me and the following albums. There are tracks that always bring me to tears. Shame on record companies for not seeing the far-reaching message he would provide, and what’s even better for them, it would earn money. (How sonically am I?) Dear Alex, he was so ahead of his time. His gravelly voice, a heart of gold. Jonsey, I did the string arrangements. Great band. At the time, I was recording for many hours a day.

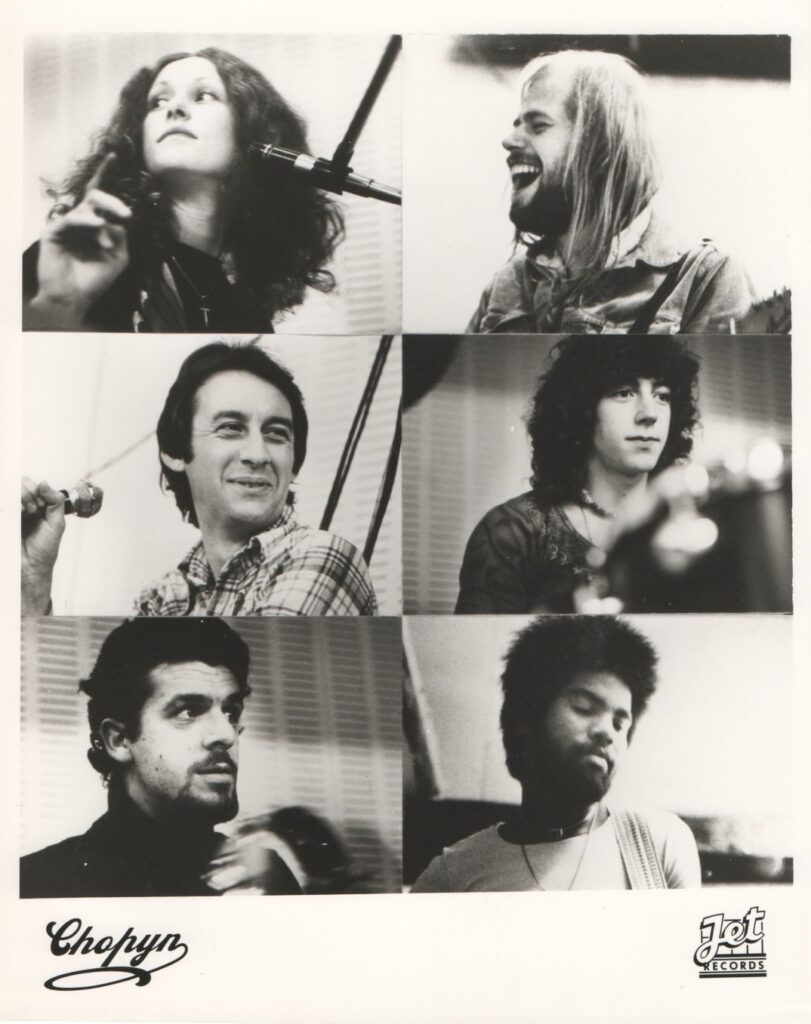

Then there’s Chopyn, another hard rock band you were a part of. Can you tell us about your time with them?

Produced by the fantastic John Punter, this record came close to being one of the best because it was a gateway record for me, as it led to ‘Ready or Not’ for DJM.

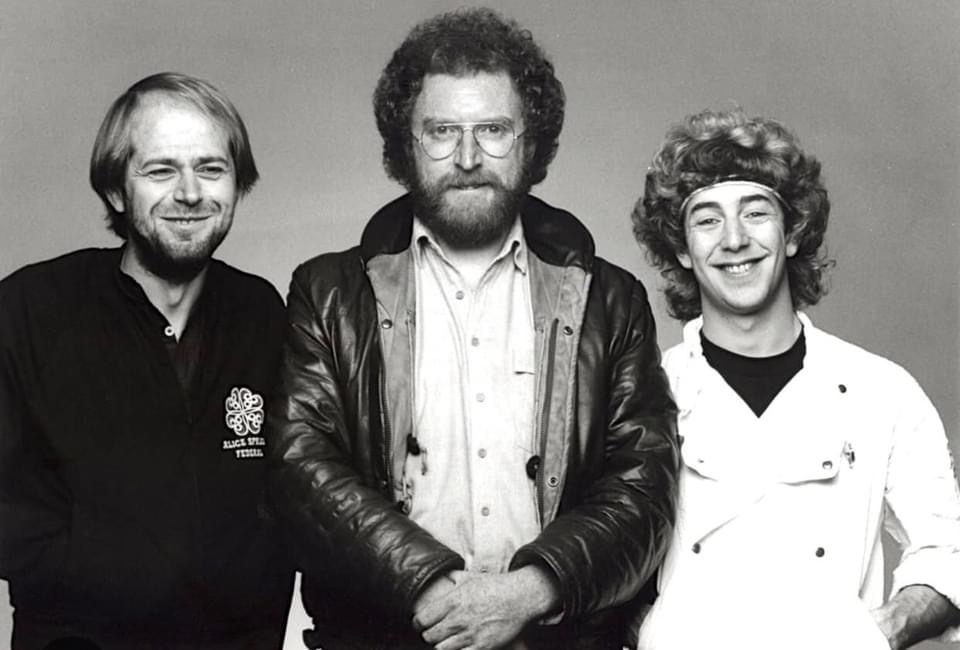

The late Ann Odell formed this band. I remember the meeting — I had worked with Simon Phillips once before and hoped we would work together again (and now, 40 years on and off!). He was there, along with Chelsea the bass player, Denny McCaffery the singer, and percussionist Simon Colclough. I think that was the album where Simon Phillips was using his first Tama Octoplus double bass drum kit.

We rehearsed and made some changes to lengthen the riffs and solos, which could be edited for a single. We worked to get it to be in the pocket, as they say. It had to be an 8-ball. We got to AIR Studios, where I frequently recorded at that time. To me, this was the best studio complex in the UK. (The original A&M studios in L.A. was my USA favorite; it was Charlie Chaplin’s old soundstage, all wood—resonance.) We overdubbed some guitar and, of course, vocals, and John produced a fab mix of the songs.

As I said, it was a gateway album, as a year later, producer Kaplan Kaye at DJM wanted to make an album with John Punter engineering and co-producing. This album featured Simon Phillips and Peter Van Hooke (Van Morrison, Mike and the Mechanics) on drums, Mo Foster on bass, Tony Hymas on keyboards, Chris Parren on keyboards, augmented with five brass, and even a string section for two tracks.

This album I put among the most enjoyable ever.

On this scale, I would also put The Album with Gil, ‘Symbiosis’ with Simon, and ‘Another Lifetime’ with Simon.

It’s the way technology evolved (keeping in mind that by the time of ‘Symbiosis,’ the democratization of the studio was well underway). New fortunes were being made by selling home studio gear. We demoed as we wrote Symbiosis, so the players could get a feel of what we wanted.

What was it like working with Harry Beckett’s Joy Unlimited?

Well, as I said earlier, this is the trumpet that smiled. He was such a happy guy. His music reflected that, and I think every album I did with him, the mood in the studio was uplifting, like a prayer meeting.

Jazz In Britain recently released a live recording of your Sextet. It’s truly fascinating—could you share a few words about that experience?

Interesting listening to what you did years ago. I remember the recording well. It was for Jazz in Britain at the BBC. All live. In fact, as it was a live broadcast, you had to make sure your gear was all working before it started. We were second on, so while Humphrey Littleton spoke about forthcoming events, we had to drag a drum kit and an amp towards the front. A hurried mic placement (now seen as archaic), and you were on. No tuners then, I had tuned half an hour ago, and that was it. It was fine, a nice gig. When I played the 1/4” copy of the gig, I had to EQ it a bit as it had gone slightly dull, and I had to do some neat nips and tucks where the tape oxide had shed slightly. No one seemed to notice as it made sense musically.

“Music is never really a solitary art”

There are also projects like Protocol, RMS, The Secret Police, Troll, X-Cess, and more. Your discography is impressive. Looking back, what are some of your fondest memories?

It would be R.M.S., as it was a power trio that didn’t seem to miss anything. Lovable, just playing with great musicians.

The essence of playing with others, especially recording, is that your sound is good; you have to adapt and create flow. You need to have put your own sonics onto the canvas and left room for the other sonics to fit into the complete picture. Music is never really a solitary art.

What was the most memorable concert you’ve ever played? When and where did it take place?

Well, two—no, alright, make it three.

I suppose Bridget Bardot’s villa in France with the Soft Machine (I played with them for a couple of years when Chris Spedding left).

Just watching these people, full of LSD, dancing to Graham’s outreach of alto cascades and really fast tempos.

Gil Evans at Montreux with R.M.S.

The Tent Festival with Simon P, Anthony J, and Tony R. Something magical happened there.

Do you have a vault of unreleased material? Is there anything in particular you’d like to see released in the future?

Yes, I’ve got stuff, but I’m working on a new project that should be ready by the end of this year.

From playing jazz at Ronnie Scott’s to sessions with Bowie and McCartney—how do you switch between such different musical worlds so effortlessly?

I live in that world of guitar where it is the common denominator of all kinds of music. Your mindset has to be to play for the song, to make your input meaningful, never to judge it, but to give it merit.

You’ve worked with legends like Georgie Fame, Jack Bruce, and Chris Spedding. What’s the biggest lesson you learned from playing with these guys?

If you’re playing in Europe, always take a raincoat!

Sensible answer: Listen, listen, listen. When you know what they are saying, you can join the conversation.

How did your experience playing in the John Barry Seven, and specifically the James Bond theme, shape your approach to guitar?

Early days. I felt happy getting through the gig. What shaped my life to become a professional musician and composer was to woodshed every tune until you could start playing it from anywhere and remember it.

This is what is invaluable when learning. People usually learn in sequences – the verse, the chorus – but you need to know where you are at all times. For instance, when you’re dropping in as a band or as one person, you might want to start recording in the middle of a bar on a repeat, and you need to know. The guys in the JB7 were all better than me, and their attitude helped me change my outlook on defining what is important in playing as a group.

You’ve played on iconic records with artists like Marvin Gaye and Tina Turner. Do any of those sessions stand out as particularly special or memorable?

The studio is a great leveller. You are exposed, and your performance is evaluated in respect to the other things happening in the rack.

Now, Tina was amazing; she sang ‘Let’s Stay Together’ in one take. Greg Walsh did another for safety, but she nailed it. She didn’t need an army of people waiting on her; she was just natural and a great singer.

So sad she’s gone.

Marvin, as great as he is, was a different story. He was silent for about 6 hours, incommunicado – a strange session. Too many people in the control room.

Not connected to M.G., but the sessions that don’t feel right or are a bit edgy are usually because too much is going on in the control room. Business belongs outside the studio.

Celestial Squid, your collaboration with Henry Kaiser, feels like a full return to your avant-garde roots. What drew you to work with Henry, and how did that project evolve?

Henry is on Cuneiform, which also has some of my catalogue.

He had liked my work for a while, and through Steve at Cuneiform, he sent me some of his records. He’s a very expressive guitar player and innovates many new guitar ideas.

I was in Vegas; I can’t remember why, but not gambling! He was in San Francisco at the old Grateful Dead studio, and he asked if I would write some tracks for him and a seven-piece band and play guitar. This was all live, and I have to say we nailed the album over the weekend and still had some hours of sleep. Henry knows what he wants from the musicians and has great communication skills.

With so much diversity in your career—composing for film and TV, session work, and your own avant-garde projects—what’s the most fulfilling aspect of your work?

I can’t really give one instance. With composing, you are storytelling, so you are like in another dimension. You have to feel for the film and also create music cues that flow with the visual.

So the ultimate buzz here is that when you present the music after a lot of sleep deprivation and the director likes it, then you’re winning. That’s a good feeling because a film is teamwork.

One Note at a Time is a great documentary about the floods in New Orleans. I loved composing that.

Album-wise, I suppose I just want my latest effort, as those tunes are still in my head.

You’re still actively performing and recording. What can fans expect from you in the near future—any new projects or surprises on the horizon?

Yes, I’m making a new album. I want it to be a real crossover album. I’m working on the tracks, so soon I’ll be recording. I want to do this live; let’s hope I can get a budget to record analogue again.

What’s currently occupying your time?

Well, composing the album and the film I devised to pay tribute to my dear friend Mo Foster has been shown at the—wait for it—Doc and Roll Film Festival. Many artists are singing Mo’s compositions and favorite songs. There’s also an R.M.S. set with my son George playing Mo’s bass parts.

Thank you for taking the time to speak with us. The last word is yours—what would you like to say?

Thank you for asking me to do an in-depth interview, Klemen.

I would probably say that I’ve enjoyed every minute of my professional life.

“Music is fluid architecture.”

Klemen Breznikar

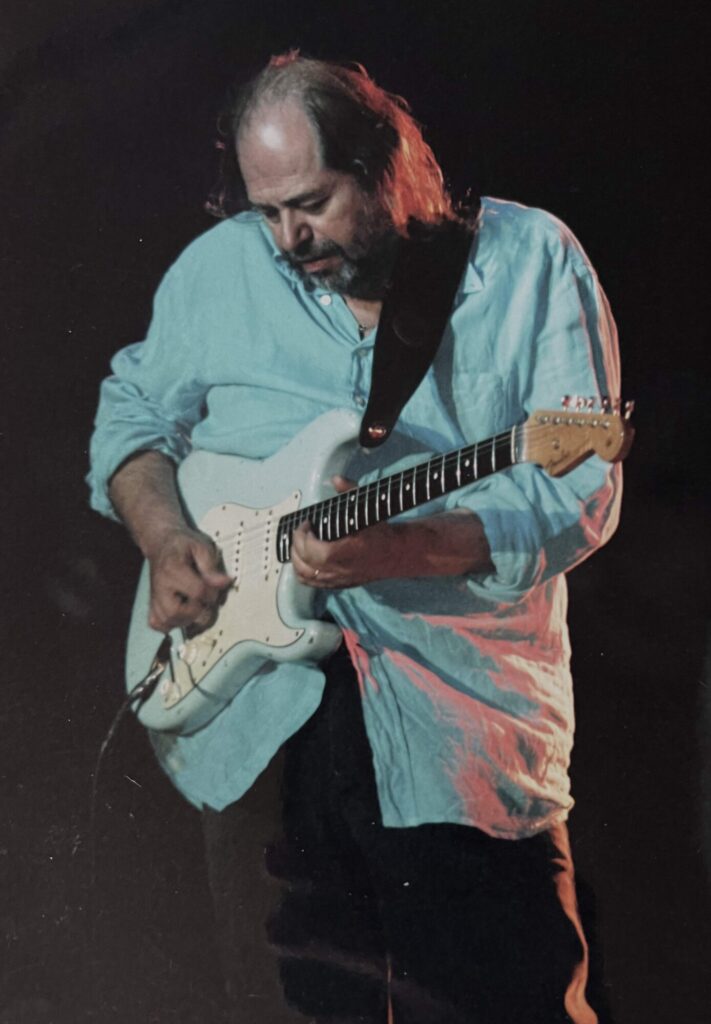

Headline photo: Running Man/Mouse | Left to Right: Gary Windo, Alan Clare, Alan Rushton, Terry Poole, Ray Russell

Ray Russell Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube