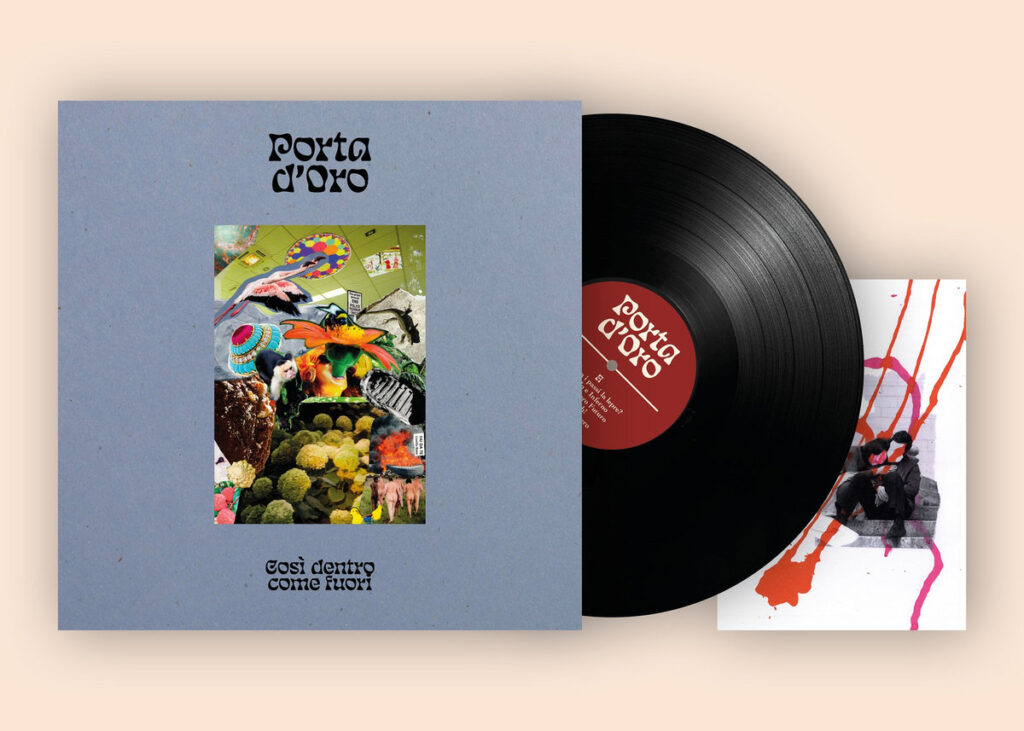

Porta d’Oro | Interview | New Album, ‘Così Dentro Come Fuori’

Porta d’Oro is a project that shuns easy categorization, fusing dub, post-punk, and lo-fi bedroom recordings into something uniquely its own.

Giacomo Stefanini’s work is as much a therapy as it is music…a journey where a scattered mind can either rebuild itself with fresh ideas or take a daring plunge into the unknown, embracing that ineffable, divine spark. His debut, ‘Così Dentro Come Fuori,’ released via Maple Death and Legno, combines raga-inspired minimalism, spoken word, and chants into a “meditative punk” experience. Taking cues from Borges, Bioy Casares, and Plotinus, Porta d’Oro’s cuts—from the pulsating beat of ‘Cielo e Inferno’ to the ambient dub-punk reverie of ‘Un Sasso Nero’ and the biting critique in ‘Conta I Passi La Lepre?’—are like sketches that dig deep and reach for something higher. Recorded entirely on a cassette 4-track, each song is built from a mix of influences: the mystic calm of Daniel Higgs, the gritty post-punk of early Mute Records, anarchic Casio fuzz, and an earthy melancholy. Nothing sounds quite like it; it’s a genuine collage of sound, scattered and free in its own world.

“Realization that there were huge parts of my personality that I had kept hidden from myself”

Your music feels like an intricate map of the mind, teetering between divine revelations and the earthbound struggle. When you were crafting ‘Così Dentro Come Fuori,’ were you more like an alchemist trying to transmute base feelings into gold, or a monk chanting in the silence of some dark monastery? Tell us more about the creation process behind it.

Giacomo Stefanini: ‘Così Dentro Come Fuori’ was born out of the realization that there were huge parts of my personality that I had kept hidden from myself: stuff that at some point I had deemed too shameful, unacceptable, or just plain painful. So a lot of the record was built on themes of encouragement to look deep inside my mind and embrace my whole self. So in a way, the alchemist suggestion you make is spot on, even though I feel like I’m still far from distilling base feelings in my music. I wish I could be more raw with it—write an angry song that is just angry without the irony, a song about pain and happiness that doesn’t rely on sophistries and over-rationalizations, etc. So, “intricate map of the mind” is a very apt description—and I strive to make it less intricate.

You’re actually not the first person to point out that I give off monk-like vibes. It may be due to the fact that I grew up in a small town built around an ancient abbey. I have to admit that the demeanor and lifestyle of monks has a strange pull on me: I dream of becoming a reclusive artist in some forsaken part of Europe, tending to my garden and making my music. But for now, I’m still living in Milan with all the urban developers and the creatives in advertising.

Borges, Bioy Casares, Plotinus—they’re all ghosts in your machine. Do you see your music as a way to resurrect these ideas, giving them a new life through sound, or is it more like an exorcism, purging the mind of their haunting presence?

Other people’s work seeps into mine very naturally. I almost don’t even think about it. To me, it’s just like when you’re having a conversation and you go, “As Borges used to say…” Back in the day, I used to put easter eggs in songs—little turns of phrase or even sounds that could make someone go, “Didn’t I hear this somewhere else?” But no one ever seemed to acknowledge them, to be honest. This time, since the song is fully based on the Borges & Bioy Casares’ ‘Book of Heaven and Hell,’ which collects tens (or hundreds?) of descriptions of heaven and hell from throughout the history of literature, religion, and philosophy, when I used the Plotinus quote, I made it really obvious. Not just because it sounded great, but also because I wanted people to be able to get more context for the lyrics using the book. I think I’m trying to create an assortment of references that, compounded with my own lyrics and sounds, will end up representing my point of view on the world—at least to my own eyes. Not an exorcism, definitely—more of an ever-evolving vision board.

“The sounds come first”

‘Cielo e Inferno’ feels like a metaphysical journey, but it’s also got this rhythmic pulse, almost like a heartbeat. When you’re creating, do you start with a concept, a philosophical line like the one from Plotinus, and let it unfold musically? Or do the sounds come first, and the philosophy follows?

The sounds come first. I just start recording and ride the wave. The beat on ‘Cielo e Inferno’ was born from my extreme discomfort with my drum machine. I made peace with it later, but back then, I was trying to find a rhythm that sounded as little like a rhythm as possible. This one and ‘Notte e Giorno’ were definitely made with that idea in mind: just to provide a backbone, a pulse, but to make it go unnoticed.

Let’s talk about ‘Un Sasso Nero.’ It’s ambient, it’s dub-punk, it’s lo-fi, and it’s a meditation on depression. How do you approach transforming such heavy emotional weight into something that’s not just listenable, but also strangely uplifting?

I think that maybe ‘Un Sasso Nero’ might be the one song where lyrics and music kind of materialized together, but I can’t really remember. It was definitely built immediately as it is: first the organ, then I could hear the drums coming in, then bass, then guitar. I played it by instinct. In fact, the first take of the song is pretty shaky on the tempo, and I would normally have kept it like that, but I felt like that little switch in the middle was too powerful to leave it so sloppy, so I re-recorded everything. I think ‘Un Sasso Nero’ and ‘O Sentiero Futuro’ are the only two songs that I didn’t record in one take.

When the album started taking the shape that it has, I said to myself: this is not going to be a sad album. I’m tired of making and listening to sad music. No bitterness, no misery, no self-hate. And I know I succeeded. There is not one sad song on the record. ‘Un Sasso Nero’ is about acknowledging the unmovable black boulder of depression lodged in my chest and letting the winds of time and self-care erode it down to a pebble. (It sounds less lame in song form.)

You’ve mentioned happiness as a “human-capitalist complication” in ‘Conta I Passi La Lepre? That track has this beautiful, contemplative tone, yet it carries a sharp critique. How do you balance the weight of such ideas with the almost ethereal nature of your sound? Do you ever worry that the message might get lost in the music’s atmosphere?

Oh no, I don’t worry. I love misinterpreting other people’s songs, and I hope people do the same with mine. It might be the highest form of praise if you think about it: when you feel a connection so deep with a piece of music that you almost rewrite it in your head, tailoring it to your feelings and ideas. I do subscribe to the idea that capitalism has poisoned humanity – I was actually very fascinated by the Hakim Bey theory that things started going south when we stopped being hunter-gatherers! ‘Conta I Passi La Lepre?’ was born out of the idea that we might be the single consistently unhappy species on Earth, and we’re the only ones who actually strive to be happy. Hares, herons, snails, toads, and groundhogs all seem very smart and content compared to us, even though they’re not “practicing gratitude” or going to therapy.

There’s something deeply personal yet incredibly abstract about recording on a cassette 4-track. It’s like you’re both building a world and keeping it deliberately inaccessible, obscured by the hiss and limitations of the medium. What’s the allure of that lo-fi, almost primordial approach? Is it about control, nostalgia, or something deeper?

When I started experimenting with the cassette 4-track, it was about convenience—and in a way, it still is. I know it sounds counterintuitive, but I really can’t be bothered to learn to record digitally and make my stuff sound good. Every time I record digitally, it sounds flat and shitty, and then you try to “dirty it up” with effects, and it sounds even shittier. All the old bands I liked were absolutely ignorant of the whole recording process, but the 4-track was so simple that they still managed to sound cool, so I figured that I could do no wrong with it. I bought one for cheap in 2007 (I think) (they were cheap back then), and I’m still using it. I like that it forces you to be minimalistic; you can’t stuff a song with layers and layers of instruments, but also it makes you look for loopholes and weird strategies to fit your ideas on the tape. Like, for example, on ‘Un Sasso Nero’ I punched in the vocals in the silence before the guitar comes in and after the organ stops to save tracks. So chance and fuckups become an integral part of your recording process. I’m less interested in the nostalgia factor, especially when the whole lo-fi aesthetic has been co-opted by those awful endless YouTube playlists “to work/study to.” It’s more about the convenience, the authenticity, and the straightforwardness of the approach.

Your sound is a melting pot—Daniel Higgs, early Mute Records, anarcho Casio fuzz—these influences are all over the place. Do you see yourself as a kind of sonic anthropologist, piecing together fragments from disparate worlds to build something new? Or is it more about creating a sound that defies categorization altogether, something that just is?

I used to be obsessed with genre. For so many years, my dream was just to be in one of those genre bands, one that could comfortably fit in a scene. But that’s just not how things turned out, and by now, I’m used to it and way more at ease playing whatever comes out of me. I’m also confident that, now that I’m in my late thirties, my influences work at a much deeper level, less close to the surface. So hopefully, going forward, Porta d’Oro will keep sounding more and more like Porta d’Oro and less like a mishmash of stuff.

From raga-like minimalism to primitive chants. Do you see your music as a form of therapy?

No, I think therapy helped me to be more accepting of myself and thus let my freak flag fly more freely. But I think it’s a basic means of expression by now. It’s also the funnest thing for me to do, both live and at home.

Let’s say your music was the soundtrack to a film. What would the film be about, and who would direct it?

I never thought about anything like this, but you know what would be a good fit? A movie based on Always Coming Home by Ursula K. Le Guin, set in this peaceful society living in harmony with nature, but with the added eeriness of a director like Alice Rohrwacher—something akin to Happy As Lazzaro.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately that you would like to recommend to our readers?

I haven’t been listening to a lot of music lately. Since I’ve been reading the book Archive Fever about the ’90s New Zealand underground, I’ve been listening mostly to old Dadamah, A Handful Of Dust, Flies Inside The Sun, The Garbage And The Flowers… But if we’re talking recent releases, the new Peace De Résistance record ‘Lullaby For The Debris’ is certainly one of the finest I’ve listened to.

Thank you. Last word is yours.

Thank you for keeping music writing alive with your magazine. It’s important, and I miss it a lot. I’ll use this space to plug my stuff: get my album ‘Così Dentro Come Fuori’ from Maple Death, Legno, or wherever you get your records, and book a show while you’re at it! Check out my band ONDAKEIKI if you’re into dub-infused psychedelia, dolphins, and UFOs. Also check out Sentiero Futuro Autoproduzioni and especially the benefit compilation PUNX FOR GAZA. Free Palestine, fuck borders, freedom for all people everywhere.

Klemen Breznikar

Headline photo: Giada Arena

Porta d’Oro Instagram / Bandcamp

Maple Death Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / SoundCloud / YouTube

Legno Website / Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp