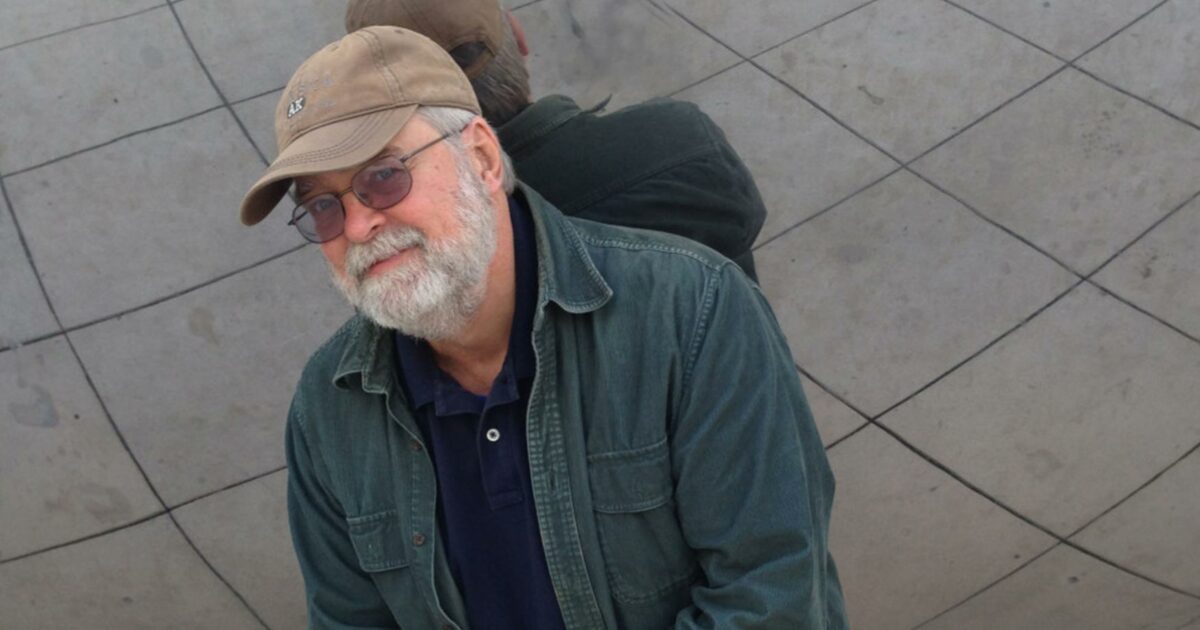

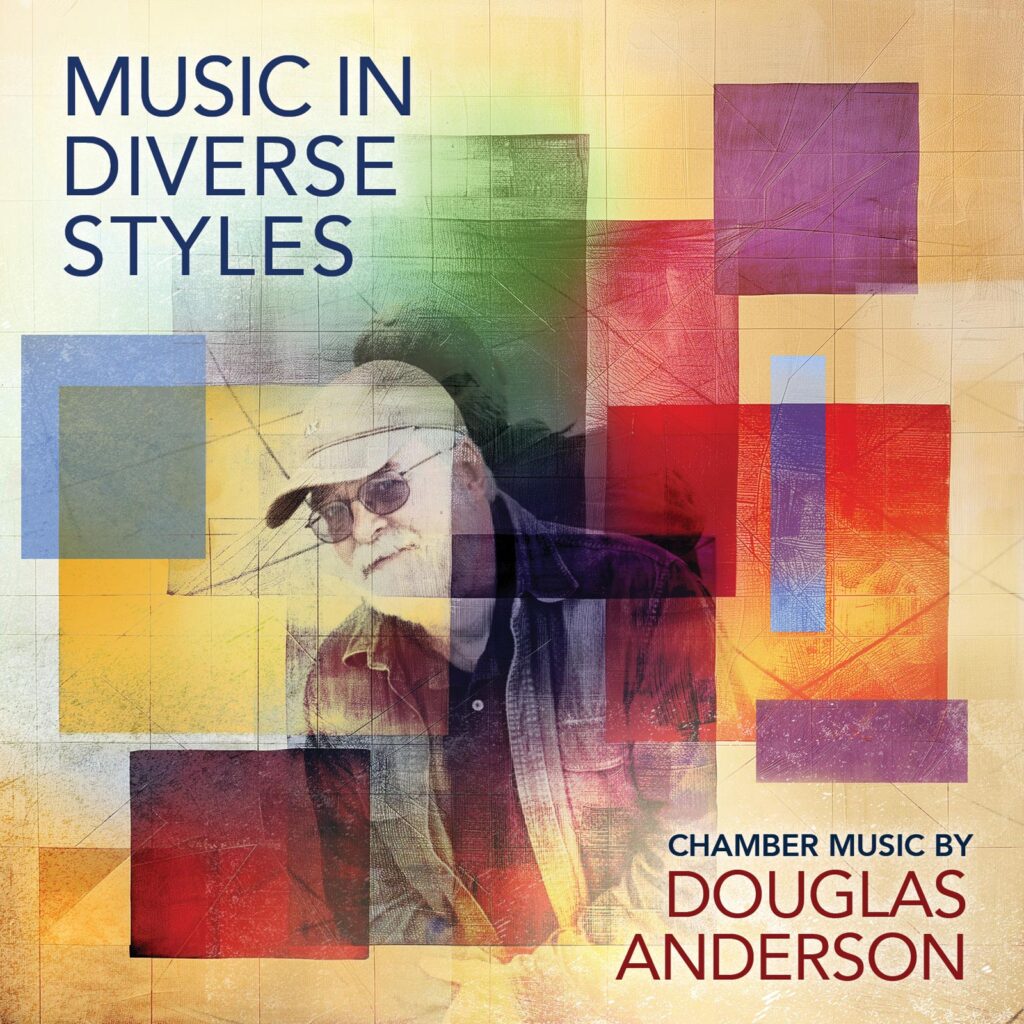

Douglas Anderson | Interview | ‘Music In Diverse Styles’

Douglas Anderson’s latest album, ‘Music in Diverse Styles,’ showcases a remarkable journey through his eclectic approach to composition.

While his music is rooted in atonality, Anderson’s work defies conventional boundaries, blending a rich mix of styles with his signature serialism. Over the course of four decades, his compositions have evolved, yet the consistency in quality and creative depth remains ever-present.

The album offers a captivating exploration of chamber music, shifting effortlessly between duos, trios, and septets. Each piece reveals Anderson’s keen ability to mold complex musical ideas into accessible, yet thought-provoking works. Despite the variety in instrumentation and style, ‘Music in Diverse Styles’ feels cohesive, demonstrating the composer’s distinctive voice across a broad spectrum of sounds. Released on Ravello Records, ‘Music in Diverse Styles’ is an exploration of the limitless possibilities of sound, all within the framework of Anderson’s unique, atonal vision.

“I’ve always been interested in learning about different musical styles”

‘Music in Diverse Styles’ presents a remarkable fusion of genres, from bluegrass to rock, filtered through your signature approach to serialism. Could you walk us through your process of integrating seemingly disparate musical languages into a cohesive work?

Douglas Anderson: The “musical languages” I use in a given piece are chosen to give me the best results toward whatever objective I’ve set out for the piece. The primary objective of every piece I write is to put sound in the listener’s ears and cause some effect in their mind. The nature of that particular effect is the first compositional decision in every piece. Once I’ve made that decision, I then make the practical decision of what musical “tools” I should use to achieve it. Throughout my life, I’ve always been interested in learning about different musical styles and their effects on listeners. I do use (when useful) traditional tonality, as well as many other organizational systems, but have found that I have the most flexibility for the development of new ideas within the serial context.

The album spans four decades of your compositional journey. How does each piece on the album reflect the evolution of your artistic vision over time?

Each piece reflects the circumstances of its conception—why did I write it? Sometimes it’s a musical idea that I’m exploring, sometimes it’s for a particular kind of event, or for particular players. From my point of view (inside the process), the timeline of the pieces reflects the increasing diversity of musical ideas I come up with, and the growth of my technical skills in manipulating the materials to a particular effect.

The title of the album suggests a conscious embrace of eclecticism. How do you balance this diversity while maintaining a sense of personal identity and consistency across your compositions?

Since my interests are so varied, I don’t worry about “personal identity”; if it interests me, that’s enough. I don’t have time for what doesn’t interest me; as a result, I’ve avoided certain compositional circumstances that would bore me. Consistency is a function of technical skill combined with how well I can define my objective.

Pieces like ‘Reverse Variations on ‘Arkansas Traveler” and ‘Rock Riffs’ showcase your willingness to experiment within traditional forms and styles. How do you see these works contributing to the broader conversation about genre boundaries in contemporary music?

It has been a long tradition in Western “classical” music for composers to use music from various “folk” or foreign sources as inspiration or a “canvas” on which to paint their own musical designs. Examples range in time and diversity from Josquin’s Mille Regretz to Bach’s Gigues, to Mozart’s Variations on ‘Ah, je vous dirais Maman’ and Rondo alla Turca, to Stravinsky’s Ragtime, and many hundreds more. My background as a jazz musician led me to an interest in improvisation, which led me to bluegrass; and of course, I grew up surrounded by rock music. Despite the difference in intent between those varied musics and my own intents in composition, I’ve always been interested in exploring musical ideas, wherever they come from. I hope that listeners will be persuaded that genre boundaries are essentially only for ease of marketing or discussion. Applying different sensibilities to various genres (as many performers do when they move to new genres) can have interesting, entertaining, even enlightening results.

Serialism often evokes notions of strict formalism, yet your works are described as playful and vibrant. How do you reinterpret the serial tradition to suit your unique compositional voice? As a composer whose music is steeped in serial techniques, how do you approach accessibility in your works? Do you consider audience perception when crafting your pieces?

The extent to which most musicians understand serialism is based on a very simplistic description they were taught in school. As a student composer, I had the opportunity and encouragement to study serialism (as well as other early 20th-century techniques) in much more detail, and I realized that by the time of my education (late ’60s–early ’70s), many contemporary composers were exploring serialism in a variety of interesting ways (what I now call Serialism 2.0)—I also chose to do so. My basic objective was to develop a version of serialism that had the same massive flexibility, or even more, that was all too evident in tonal music. My doctoral dissertation reflects the beginnings of that exploration, which continues to the present.

Simple serialism involves “rows” or series that maintain their sequence of pitches (but in later versions, units of time are used to create rhythms) in various simple transformations—prime, retrograde, inverse, and such. Searching for the flexibility of tonality (after all, most tonal pieces are much more than scales and simple chords), I came upon the idea of ‘unordering’ the rows—suddenly, gradually, sneakily, and so forth. The musical materials of my serialism can be heard to maintain the coherence of early serialism but also have tremendous melodic and harmonic flexibility.

This flexibility allows me to write music that most listeners won’t recognize as obviously serial. The idea of audience perception is always on my mind (see objectives above); I’m always trying to manipulate the audience’s mood with my music. (I was, after all, a psychology major in college for exactly this purpose). But with the understanding that any given audience has a great variety in degrees of musical education and experience, I am also trying to reach all listeners.

So, while there may be within a particular piece some ‘exciting’ new ideas about serialism to entertain the “serial geeks” (yes, they exist), I also try to entertain those who’d rather be dancing, or meditating, or whatever. Not every piece can do all things for all people (that’s why there are different types of music to begin with), but I try to have multiple levels of objectives—and hence my diversity of titles, to put the listener’s mind in a particular frame before the piece begins.

Your chamber works, such as the Chamber Symphonies, have received critical acclaim for their complexity and emotional depth. What draws you to the chamber music format, and how does it challenge or inspire you differently than larger orchestral works?

The answer to the first part is rather prosaic: it’s easier to have smaller works performed, and since I know a lot of instrumentalists from my conducting life, I get many commissions that way. The challenge of chamber music is its intimacy, as compared with larger groups. The more instruments/voices, the bigger the sound, and the greater the impact simply as a result of dynamics. There will be, in the future, an album (or three) of my larger works, where I take advantage of that impact. But in chamber music, the impact has to come from fewer ‘physical’ resources than loudness—actually a more difficult task.

Having started as a jazz musician at 12 and later delved into atonality and serialism, your musical trajectory is extraordinarily varied. How did your early experiences in jazz shape your approach to composition?

I loved (and still love) to improvise and to hear people improvise, especially in groups. As a growing jazz musician, I became aware that the directions my improvisations took (when left on my own) were not so “commercially” acceptable. Around that time, I took my first composition class, where I discovered that I could edit—go back and do it again a little better, or a little more focused. So composition became my focus. Many people have “identified” various things in my music that sound “jazzy”—I like to think that occasionally it’s a little of my native accent (jazz) coming through.

You’ve conducted everything from Broadway performances to avant-garde premieres. How has your work as a conductor informed your compositional process, and vice versa?

As a conductor of a wide variety of groups and styles, I’ve always thought of myself as the composer’s emissary—taking the indications given in the music and trying to faithfully reach the objective the composer set for us. Since I am a composer, I have always tried as a conductor to remember that the piece I’m conducting was new once (in premieres, it’s literally true), and to get into the head of the composer: what is the point of this melody, phrase, section, piece, as laid out in the composer’s instructions (the written music)? And of course, any interesting idea I find along the way is worthy of investigation, and if appropriate, imitation in my own music (the highest form of flattery). My ‘Chamber Symphony No. 2’ is a good example—I (quite deliberately) quote or imitate Mozart, Josquin, Shostakovich, and many other composers.

You’ve often collaborated with librettist Andrew Joffe on operas such as Medea in Exile and Antigone Sings. What do you value most in your collaborative relationships, and how do they influence your creative output?

My work with Andrew Joffe has been a great pleasure of my compositional life. He writes words (and ideas, and stories, and librettos) that I find immediately inspiring. Prior to working with him, I wrote vocal music with a variety of writers whose work interested me, but once I worked with Andrew, I was hooked. And the collaborations also extend to singers and instrumentalists, for whom I have written many pieces. The idea mentioned above of ‘objective’ of a piece comes not just from my head, but also from conversations with musicians about what a piece of music could do, and how.

As an educator and former department chair, you’ve shaped the musical journeys of countless students. How has teaching influenced your perspective on music and composition?

Teaching has always been very enjoyable for me. The main impact it has had on me has been the multi-decade observation of college students and their changing interests and styles. The direct conversation about why they listen to music has always been a starting point of my classes. It has allowed me to introduce them to different reasons for listening to music, which has allowed them to teach me to see/hear things in different ways. And of course, my students kept me up-to-date with ever-changing trends in popular music.

With decades of experience in composing, conducting, and teaching, what do you see as your most significant contributions to the musical world?

In teaching, the idea of opening minds to new ideas has been a major thrust. In conducting, bringing new and unusual pieces to the musical world, as well as new ways of thinking about well-known works. In composition, the idea of planting music in people’s minds to help them see new worlds and ways of thinking. All of these activities are part of the same basic thrust: put music in people’s ears to mess with their minds.

“The “universal language of music” means (to me) simply that people want things from music…”

Your works have been performed internationally, from Voice of America broadcasts to NPR. How does engaging with global audiences shape your understanding of the universal language of music?

The “universal language of music” means (to me) simply that people want things from music, and different cultures have certain basic “needs” that can be met by their music, as illustrated by how those local musics evolved. I’m very interested in music from all cultures, and thus find it disappointing to hear that many cultures around the world have been ‘colonized’ musically by Western pop music. I always prefer to hear the original music of different cultures.

One of the curious things that happens when my works are played outside of my hearing is that people respond and occasionally report back to me. I’ve been approached by people who heard my music, remembered it, and could describe it and its impact on them, often in ways I hadn’t anticipated. Recent promotional activity has resulted in measurable interest in my music in Turkey, Hong Kong, and Singapore (places I’ve never been so far), as well as more traditional places for Western concert music (Europe and America). I haven’t yet had a chance for a world tour where I’ll have the opportunity to interact personally on a larger scale—something to look forward to.

Given your ability to work across genres, formats, and technologies, how do you see the role of the composer evolving in the 21st century?

The “role of a composer” will probably remain the same in the sense of what I’ve alluded to above: what do people want in/from music, and how to give it to them? The 20th century gives us clues about the development of technologies and composers taking advantage of them (e.g., My Piece for ‘Clarinet and Tape’). The development of artificial instruments will be impactful, but I think there will always be a need/desire for live performers and performances. The most impactful may be AI, although in its current development, it can only repeat what it has already discovered. A truly creative musical AI will need to address the questions I ask of myself: what is the objective of this piece, and how best to achieve it?

Reflecting on your career, from the premiere of In Memoriam after 9/11 to your latest release, ‘Music in Diverse Styles,’ what moments stand out as particularly defining or transformative for you?

I long ago abandoned consideration of my career—I figured it would happen as it does, based on the work I do, and as long as I’m doing something musically interesting, I’m happy. I don’t really experience “moments” as transformative; rather, my accumulating experiences give me more and more material to work with. That said, I’ve been extraordinarily blessed to have worked as a conductor and composer with so many great musicians, and have conducted so much great and diverse music, continually learning from those experiences. Perhaps those are the incrementally transformative moments.

What excites you most about the current state of contemporary music, and where do you see opportunities for innovation?

One of the most exciting things I’ve experienced recently has been the rise in quality of music on television. The boom in platforms for new video programs (Netflix, HBO Max, etc.) means that with all the new shows of wildly varying types, there are a lot of composers working on them. I wondered in the ’80s, ’90s, and ’00s where all the composers would go, highly trained at great universities by great teachers: academia was the main option when I was studying composition, so I went that way. But now, I find I’m often listening to the excellent, well-crafted, and powerful scores for the various programs my family watches, and even find some writer/directors who understand and creatively use music in their shows.

The greatest opportunity for “innovation” in these times is actually a return to the past—to a time where composers are writing more than just descriptive music. For many years, as the “TV” generation grew up, new concert music was overwhelmingly descriptive, rather than compositionally interesting in non-descriptive ways. Back to the past—Beethoven’s symphonies still have a tremendous impact in concert (my students are always wowed), but are rarely descriptive.

Are there new directions or projects you’re currently exploring that push the boundaries of your artistic practice even further?

I’m always looking for that, and indeed, some new ideas are on the table. But nothing to report until it’s ready.

Finally, what do you hope listeners will take away from Music in Diverse Styles, and how would you like this album to be remembered in the context of your body of work?

I hope that listeners will find something among the diversity that immediately appeals to them, and that makes them want to investigate the rest of the works, and indeed the diversity of the albums that preceded it: ‘Chamber Symphonies 2,’ ‘3,’ and ‘4;’ ‘One at a Time’ (solo instrumental works); and ‘What She Saw’ (dramatic vocal works). And I hope listeners will explore the albums that come next: ‘Songs and Such’ in late 2025, and more.

Klemen Breznikar

Ravello Records Website / Facebook

Parma Recordings Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube