Radio Massacre International | Interview | New Album, ‘Galactic Furnace’

Radio Massacre International, the UK-based instrumental trio, has built a unique reputation for their intense electronic improvisations laced with the heavy, cosmic influence of space rock.

Over the years, they’ve developed their own style, blending hypnotic atmospheres with bursts of intense, improvised energy. Their latest album, ‘Galactic Furnace,’ out via Cuneiform Records, stays true to their legacy of sonic exploration while offering a glimpse into where they stand creatively today. From the meticulous layers of synthesizers to the intricate, rhythmically driven passages, ‘Galactic Furnace’ is a stunning example of 21st-century cosmic vision.

As the band puts it, “’Galactic Furnace’ was made over the course of a week, in the middle of summer, in beautiful North Yorkshire. We inhabited a cottage space which was very kindly loaned to us by a good friend and unlike many recording environments, it was extremely pleasant with plenty of natural light and air. As is our wont, we always keep a live microphone somewhere in the mix and this one was outside on the decking pointing towards woodland and good old Yorkshire countryside. This album is unique, you could say, because it was recorded in this certain space which we know will not be available to us again (it now belongs to someone else, we didn’t trash it or anything).”

“We just do what we want.”

Could you describe the initial creative spark that brought the three of you together as teenagers, and how your chemistry evolved into the distinctive trio format of Radio Massacre International in 1993?

Gary Houghton: I’m not sure what the initial spark was, but we were all into improvised music and the concept of just plugging in and seeing what came out. We also used to hang out in the same pub and spent many nights staring up at the skies on the way back from the pub. Those skies were black and full of stars, really quite awesome. I live in a big city now, and the skies just aren’t the same because of light pollution. I am sure they were inspirational to us. This was back in the late ’70s and early ’80s. When we reconvened in 1993, it was like we’d never stopped. The very first thing we recorded was a 60-minute piece, which has since been released on Bandcamp. And it sounds so fresh!

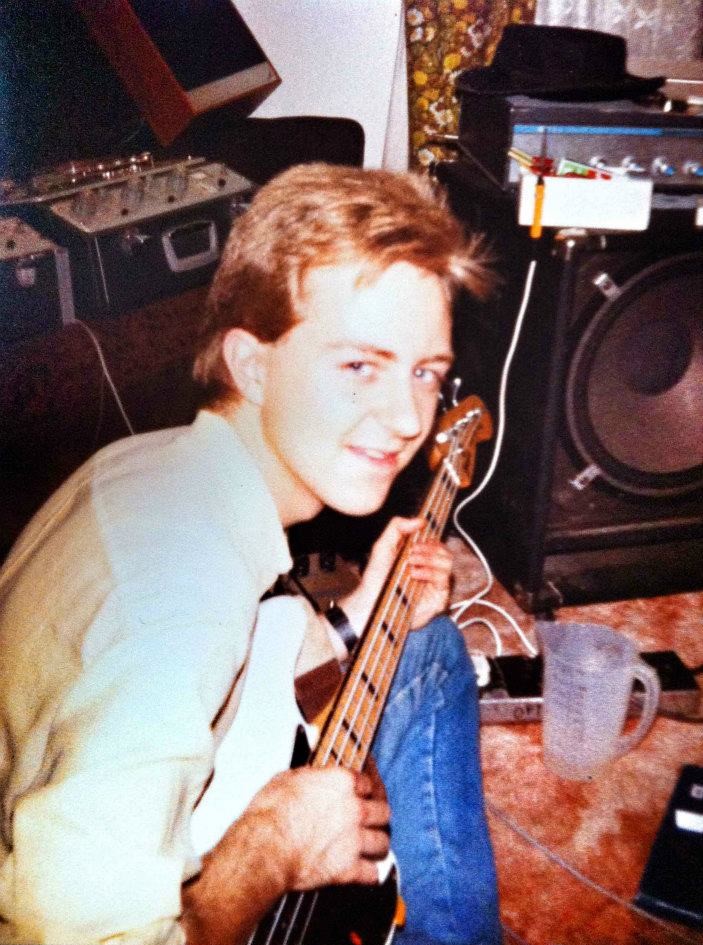

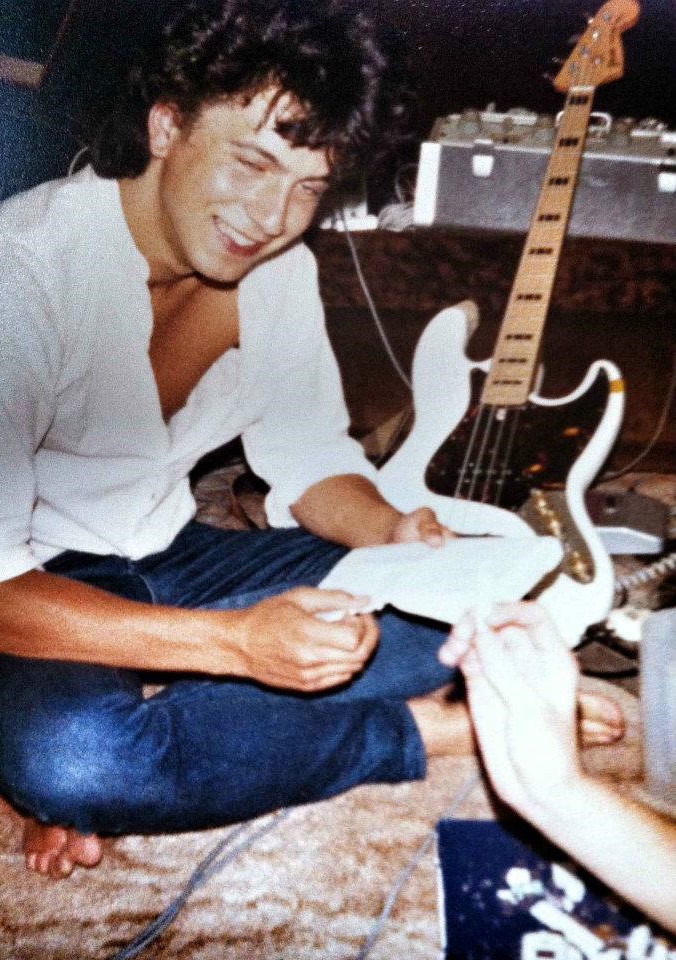

Duncan Goddard: As I recall, Steve and I had been asked to join a space-rock band led from the drum kit by one Mark Spybey, who’s had quite an interesting career himself! We were later joined in this band by Gary, who was just starting on the guitar. One big impetus for us to begin writing and later recording our own compositions was dissatisfaction with the output (quality and quantity) from our favorite bands. Steve described a lot of the electronic music of the time as “complacent,” while we definitely all felt that there were areas being left unexplored in the space between heavy rock and electronica.

In a break from this band, the three of us gathered at my house and made our first baby steps with a borrowed Revox; this became DAS 1 and was recorded between 23/12/79 and 2/1/80.

So we’re a ’70s band—just!

Various things—life!—separated us until late 1993, when Steve was able to visit the collection of synths and whatnot that I had accumulated in the years between. We quickly got into an almost telepathic state again, and after a few sessions, we met with Gary and announced that we had started recording again.

“When do I get to do my bits?” he said. And so we were again a trio.

Steve Dinsdale: Duncan had been experimenting with electronics and tape recorders at home, and this led to us both meeting Mark Spybey (Dead Voices On Air) when we were 16 and starting a space-rock band together with the aid of a Roland SH-1000 synthesizer borrowed from the college we were attending in Northeast England. We met Gary around this time through a friend of Mark’s, and he joined the band too.

Away from the noisy band practices in our local church hall, Duncan, Gary, and I began experimenting with the synthesizer in Duncan’s studio, with tape echo, overdubbing, etc. The results of this can be heard on DAS 1, which was a cassette released in 1980 on David Elliott’s Neumusik/YHR label. Over the following years, DAS made many recordings with a variety of people, all centered around Duncan’s studio—enough for 12 albums’ worth. We have released several of these on Bandcamp, including DAS 1.

By 1993, we’d all had a lot more life experience (and, in some cases, record business experience… I was holding down a day job and playing in indie bands), and all the while, Duncan had been slowly accumulating keyboards, composing his own stuff, and putting together a recording environment. Duncan and I were, at the time, living only a few miles from each other in London, and when I’d had enough of the indie world, the time was right to start exploring different possibilities. We were thrilled with the early results we achieved, improvising straight to tape, and it was the logical next step to invite Gary to come down and contribute. This was an immediate success, and the very first piece we recorded (Drown) is now on Bandcamp for all to hear. We recorded two further pieces the same day (Diabolica and Upstairs Downstairs), and we were on our way.

Gary lived 250 miles away in Manchester, so he couldn’t always join us, but those first few years, when Duncan and I lived so close, meant that we could have day jobs but still have time to record in the evening. It was a wonderful burst of creativity.

The name “Radio Massacre International” carries a sense of provocation and intrigue. What was the origin of the name?

Duncan: All three of us, at some point in 1983, had felt the need for some sort of cathartic release—by way of an almost unmusical noise—away from the restrictions and conventions of normal band activity. We plugged a Casio and a Moog straight into a cassette deck—no effects—and got things out of our system. Not much of this racket is listenable now, but we remember it fondly… the dumb drum box in the Casio, the circuit-bent Moog Prodigy, the fizzing distortion.

One day, Steve assembled a load of this stuff onto a cassette and presented us each with a copy. The name was already in place.

By the end of 1989, Steve and I were both in London—still a few years away from properly restarting the band—but we had recorded a few things already. On the very edge of 1989 changing into 1990 (a nice bit of symmetry), we decided to use the “Radio Massacre International” name for anything and everything we did thereafter.

Steve: Back when we still lived at home at our parents’ houses, occasionally Duncan and I would hang out at my place for a change of scenery. I had next to nothing by way of technical gear—just a couple of keyboards and a cassette deck. For amusement, we would plug a keyboard each into the ¼” jack sockets on the front of the deck and just make a very abstract and unappealing noise, with no effects or anything.

One day, when I was listening back to a cassette we had just recorded in this way, the name just came to me to differentiate this noise from what we were seriously taking time over in DAS. This was 1983. It was ten years later that we were looking for a more interesting name than DAS, and “Radio Massacre International” seemed to really fit the bill.

Would love it if you could talk about the initial beginnings with the formation of DAS and how that evolved…

Duncan: As mentioned earlier, the three of us peeled away from the band we were all in, feeling that the band rehearsal environment wasn’t really letting us develop any writing or arranging skills. We had also begun to have ideas for orchestrating our sound that weren’t possible with one synth and one guitarist. I played engineer, for the most part, and only added synth or electronics by way of overdubs; mostly, Steve and Gary would work out the parts and how they were to be layered, though I would keep reminding them of the technical constraints.

We were recording straight to two-channel 1/4″ tape, and adding layers each time was a constant struggle against hiss, dropouts, and so on—especially as we were kids and didn’t have a lot of money for fresh tape. So there would be discussions about which parts needed to go down first and how to balance everything to leave sonic space for the subsequent layers, with great care not to bury the first layer in either more parts or tape noise.

The equipment was basic, but we got the most out of it that we could, learning about levels, mic placement, syncopation of tape delays, and so on.

We went our separate ways on leaving college at 18, having missed out on a record deal because we couldn’t go to meet with them (school the next day!), and really, that was it until 1989.

Steve: As I said previously, we were somewhat keen to see what we could squeeze out of the Roland SH1000 in a more controlled environment, and each term break, we would convene at Duncan’s in his attic room and see what happened. Sometimes, there would be other friends involved—Duncan was the only absolute constant, the Joe Meek of Teesside, working miracles with a UHER, a Ferrograph, and a cassette deck or two.

We usually made a piece each day until we had an album. There are 12 such albums recorded over the early to mid-’80s. We’re very proud of the fact that we began our first album in December 1979 and therefore qualify as a real ’70s band—if only by a hair’s breadth.

“…a near-telepathy in our largely improvised performances and recordings”

How did the “Berlin School” sound of Tangerine Dream and Klaus Schulze shape your early explorations, and how have those influences evolved or been deconstructed in your work over the decades?

Gary: It didn’t have much of an impact on me. I was more into Hawkwind than the Berlin School. And Here & Now.

Duncan: We always used to tell people, “If a band uses two guitars, bass, and drums, do they automatically write songs like The Beatles or The Yardbirds?” So it is with this Berlin School label—we use synths, sequencers, a Mellotron, a guitar… but our background, our behavior, our personalities—totally different.

A surface reading might put someone in mind of a certain period of TD’s output, in the same way that (in the ’60s) you might have heard someone’s dad saying of The Beatles, “All these guitar bands sound the same! Get that bloody racket turned down!”

We believe that there is a definite character to our output that makes it instantly identifiable amongst the mass of BS-type music that people are making. Central to that is the long relationship we’ve had, both musically and socially, which has engendered a near-telepathy in our largely improvised performances and recordings. This is critical to our music and should not be underestimated. If you are making art—expressing emotions or ideas via your instruments—and there are other people engaged in the exact same piece of art at the exact same time, you’d better be on very good terms with them, or it won’t work.

I have watched improvisational duos, trios, quartets… in the studio, on stage, and I despair at the poor ergonomics of their setups, the lack of eye contact…

So when Steve (or anyone else) refers to our music as “organic,” this is what they mean. It is a conversation—three mates who’ve known each other a lifetime, looking at the stars or the sea and pondering the mysteries of life. This is not the case with most of the music, improvised or otherwise, that one hears—especially in the world of electronic music, where it seems to be more important to have a ton of equipment than to have anything to say with it.

Steve: It is without question, of course, that we were influenced greatly by these pioneers, especially the classic Tangerine Dream line-up of Froese, Franke, and Baumann. Ricochet remains one of the few perfect, unique albums in any genre, without a doubt. This was the music that taught us a new way of listening, and ultimately, as a young person, the first instinct is to imitate your heroes (ask The Beatles!).

The problem initially was, of course, that we weren’t sitting in a studio packed with Moogs, Mellotrons, and VCS3s, nor could we have even dreamed of such a situation, but we made the best of what we had. I used to play sequences manually because we didn’t have a sequencer, and Duncan would come up with ingenious ways of making new and interesting noises! Gary came to it with a rock guitarist’s sensibility—he wasn’t really a fan of the Berlin stuff and still isn’t—but we all agreed on Hawkwind and Steve Hillage as primary influences too.

We soldiered on with various sequencing solutions, and Duncan recorded a lot of solo material featuring written parts, but what we wanted was a way of step sequencing that we could play on the fly… and that’s what you really should do with a step sequencer—play it! Don’t just let it churn out the same thing.

By 1993, we were still waiting for the missing part of the puzzle, and it arrived in the shape of the Doepfer MAQ sequencer. Up until then, everything had to be painstakingly pre-programmed note for note—and where’s the fun in that? Now we could set this thing running and create amazing sequences out of nowhere (see Scud—the very first thing we did with the MAQ). The skill in sequencing, of course, is knowing when you’ve got a good one, or what steps you need to change in order to make it a good one. You need a special ear for this kind of thing, which is not something that people acknowledge.

Now, what comes into play at this point is that, age-wise, by 1993 we are 30—we’re not 16-year-olds anymore. So, finally having these tools at our disposal, the desire is to explore our own territory rather than emulate our heroes. It remains, of course, a way of making music that can never fully escape its influences, but as we’ve always insisted, our firm belief is that you can always tell when it’s RMI in a blindfold test.

“Improvisation is where the magic happens”

Improvisation is central to your music. How did you initially approach this as a trio, and has your methodology or philosophy around improvisation changed over the years?

Gary: Gary: The approach is still essentially the same, though we have experimented with more arranged stuff at times, for example, on ‘Rain Falls in Grey’ (‘RFIG’).

Duncan: I don’t have a great recollection of there being a decisive moment regarding the approach to a new piece of music. Often, there would be the bare bones of an arrangement or an idea, and the structure would emerge as we tried out different sonic strategies. Sometimes we’re empty-handed at the start, and something just coalesces out of the fog in the room.

Personally, as the chief engineer of all this, one of my roles is to periodically visit the ergonomics, arrange new gadgets, and create new patches that I think will serve our common purpose. This, too, feeds into whether we’re completely improvising, working around a pre-arranged structure, or (and yes, we’ve done this a few times too!) playing something almost exactly “like it is on the album.”

But ultimately, in our band, we are not there to play the hits. We are not there, in fact, at all to please the audience. People struggle with this concept… we have never seen the justification in any sort of artistic compromise: if we don’t like it, it’s out. If we do like it, it’s in.

So… when we started using the drums (because we wanted to), there were a few raised eyebrows among the purists. We don’t pay any attention to this kind of thing—we just do what we want.

Steve: Improvisation is where the magic happens—the things you couldn’t have pre-planned. It is the combination of three people that makes the music so much more interesting than that of solo artists in the genre, because the other two do not know what the individual is going to do, so there is always the element of surprise.

Initially, as a trio, Gary fitted right into the new way of working because we all picked up on our previous experience making music together, and he was not intimidated by all the electronics. We hooked him into it all so that he could create loops that were in sync with what we were doing. It was surprisingly easy, if I’m honest—only easy because we’d spent a lot of time imagining when we might have the capability to work this way. It was more like a feeling of, “Here we are at last!”

I don’t believe the methodology has changed significantly, only that perhaps we have become more daring. My favorite parts of our music are when it sometimes goes down to almost silence. There is a magic, a confident beauty in those moments.

Philosophically, it’s like a state of grace where the conscious mind only plays a part. If you can leave thought out of it and contribute in the moment, you can sometimes surprise yourself with what you play. The ultimate is when you are listening back to a piece you’ve made, and everyone is so integrated that it isn’t always obvious who is doing what. That, to me, is successful improvisation.

From the Jodrell Bank observatory to the cottage in North Yorkshire where ‘Galactic Furnace’ was created, physical spaces seem to play a vital role in your music. How does the environment influence your compositions and recordings?

Gary: I am not sure… but it does! It’s like the fourth member of the band. When I listen to our stuff, I am always taken right back to the recording environment, whether it was in London, Stockport, or Castleton.

Duncan: Very much so. But the environment can be wildly different, alien to us (e.g. a radio station in LA, a cabin in the back garden of a friend’s house in Yorkshire, a pub in North London on a bill with several mid-’90s Britpop bands), and somehow we make it our own. I guess once we are set up and happy with our sounds, eyelines, bottles of water, bananas… we can turn any space into an R.M.I. space.

Steve: One thing that becomes immediately apparent when listening to our recorded history is that there is an indefinable but identifiable difference between music we have made with and without an audience, although each has its merits.

We are very lucky to have performed in some wonderful spaces and venues, including churches, planetariums, and a few really decent concert halls. Ultimately, though, it comes down to the feedback loop between what you’re playing and how well you can hear what you and everyone else is playing—and the studio will always be best for that because volume is easier to control.

Having said that, there is a magic in looking at an amazing light show going on against a backdrop of stained-glass windows, which makes the music merely a significant part of a larger event.

Your albums are distilled from live, improvised sessions. What criteria or instincts guide your editing process to transform spontaneous creations into cohesive works?

Gary: This is very much Steve and Duncan’s department! Essentially, they distill the piece down into a final form. I have no idea how they do it!

Duncan: We have some unwritten rules about this. Steve has been responsible for the majority of the editing, though I have also done quite a bit, and a lot of the time, it’s a collaborative process, which occasionally leads us into a nightmare of version control, especially when the recordings have been done multitrack.

When we started out in the current incarnation, we recorded directly to an open-reel machine (a Revox PR99 Mk1) or to DAT; this tended to dictate the length of the piece, though typically an hour was about the maximum we’d play anyway, before one piece (and, by extension, one set of musical ideas) was thoroughly mined. Afterwards, we would edit this as much or as little as needed, the main criteria being to keep the narrative arc coherent (and in the same order it was created and recorded) while removing any wasted time along with any technical issues—bum notes, other electronic glitches.

It’s not an easy process to describe, but if you’ve had to edit text or have been involved in making a movie, it will make more sense to think of the overall structure as having its own purpose, its own life, and allowing that to be the guide. Some of our pieces resisted every attempt to shorten them, while others seemed to present themselves as chapters of a larger story.

Examples of the former: ‘Startide,’ ‘Burned & Frozen;’ and of the latter: ‘God of Electricity,’ ‘Maelstrom.’ The new album has elements of both.

Steve: Looking at a new, unedited piece (and I must have done hundreds by now) usually follows the same process. I’ll make a few notes with timings and do what I call a “macro edit.” The piece might be an hour long, but the last 20 minutes might be tedious, repetitive, or overlong. Or a piece might be hovering around at the start before it shapes itself into something good, or it might lose its way in the middle. I make these macro edits first and ditch the stuff we can afford to lose completely.

Then I’ll take what’s left and look at it in more detail, first removing bum notes, technical mishaps, and, again, sections that just maybe go on too long. It’s normally the sequences you have to be wary of outstaying their welcome. I’ll get a first edit, which will give a new perspective, and it might be good to go, but there will usually be a few further cuts here and there just to tighten it all up while retaining the spontaneous aspects.

Interestingly, across the board, there is an average success rate of about 66–70% per piece. We were lucky enough to be in at the early stages of digital editing (I had access to the early SADiE software in the ’90s) and have been able to use it very much to our advantage on virtually everything we’ve done, certainly since 1996.

You’ve long embraced vintage instruments like the Mellotron. How do these tools shape your sound?

Duncan: I’m not sure that they do. They’re a part of our sound, for sure. Going back to that earlier metaphor, I think there will have been times when George Harrison was inspired to try something out for the lads by having been given an early model 12-string Rickenbacker, but I think those songs would’ve been written anyway.

We started out with one Roland synth, but it could easily have been an ARP or a Moog. Chance led me to the Mellotron, and while we made a thing of it for a while, we quickly got tired of it being the center of attention. I like the quality of the sounds that we get from it, but sound design is only a small part of a much bigger picture for us. We’ve never schlepped a huge wall of modular synths or paid much attention to any sort of arms race in this context.

I’ve gone shopping mainly for things that will give us a lot of sonic bang-for-buck and that are compact and reliable. The Mellotron is anything but these things, but it gave us a particular sound back when there wasn’t another good way to get it. I got very good at making convincing replicas of the tapes we had for my samplers, and this led to creating sounds from scratch using the same techniques—complex modulations and so forth.

But I don’t really dig into sound design like some folks do—this holds no appeal for us, especially when there’s a musical idea waiting to be realized. Some synthists go so deeply into sound design and patching that it seems to be an end in itself; we’ve never been that way. For us, if it takes longer to get a good sequencer or keyboard sound than it does to (say) make a Strat sound like you want it to through a Marshall Plexi, then time is being wasted.

In short, we stick to tried-and-trusted sounds as if we were just normal people in a normal band.

Steve: The simple answer is that they sound better. Their quirks, their eccentricities cannot be duplicated. In a practical sense, they are a pain, of course, but we have used the Mellotron and, more recently, the Rhodes, and you can tell the difference.

We had one glorious week with the Rhodes in 2011, and it sounded like liquid gold… then the speakers blew up, and that was it. The cabinet it came with was the key to the sound, with adjustable stereo tremolo, which was just beautiful. The cabinet was irreparable, so we sadly had to dump it.

The Mellotron was retired from road use after a sensible length of time—we figured people had had their chance to see it! Ultimately, it’s the difference between renting a van and getting everything in a car. In fact, our first trip to the USA was what made Duncan rethink our technical requirements, making them small, mobile, and intelligent, which meant ditching the big stuff.

Of course, when we got to the USA, there were people only too happy to loan us their instruments to use, which we gratefully did.

At the concert we just played on November 9th this year, we had every intention of using the body of a Minimoog for sequencing, but it packed up on the last day of rehearsals. So, using this old gear does come with its hazards.

In recent years, you’ve incorporated bass guitar, acoustic drums, and even vocals in some live settings. What drove this evolution, and how do these elements complement your electronic foundations?

Gary: I guess we’ve always strived to do the best we can. It’s that organic thing again—the music just goes where it wants to!

Duncan: I probably answered some of this above. The short version is: we do what we want. At any given moment, what we each hear in our heads is what we strive to get out of the speakers and into the air. There’s no strategy beyond doing what we want to do. We seldom discuss it. A conversation might go like, “Will there be drums on this?” “Yeah… that’s an idea…” And then out comes the bass too.

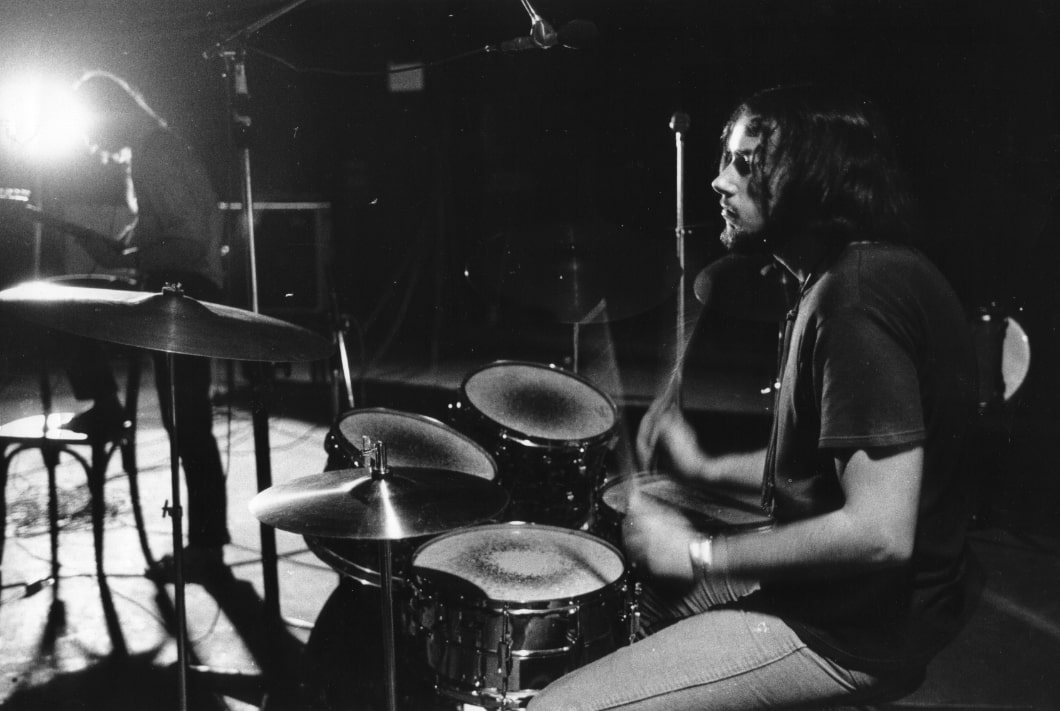

Steve: What drove this evolution is that, as a core trio, Gary, Duncan, and I are a guitar, bass, and drums outfit. We were jamming together and with others on these instruments when we were 18 and have always kept them up. Duncan is a huge bass enthusiast, and I still regard drums as my main instrument. In rehearsal sessions for electronic shows, we’d find ourselves jamming with bass and drums for a bit of light relief—because we so rarely get the chance. It seemed logical to start incorporating these elements into our own music. They are literally different strings to our bow, as it were, and we don’t see them as mutually exclusive with electronics. You have to use everything at your disposal, and even in an electronic context, we’ve always seen ourselves as rock musicians.

You’ve described your work as “organic music.” Could you expand on this concept and how it informs your creative approach compared to the more clinical aspects of electronic music production?

Gary: Our music reflects how we were feeling at the time and the environment we were in.

Duncan: I think I may have covered this earlier—telepathy and a sense of telling a story or describing an emotion, a state of mind. We talk very little before or after a session—maybe a brief discussion of the mechanics, especially if there’s a new gadget or one of us has a musical idea that needs incorporating. We absolutely never talk during a performance, either on stage or in the studio, unless something’s on fire.

Steve: I guess organic described it best for me back then and still does. I like to hear the evolution of a piece happen in real time (or close to it)—the possibilities to explore with the sound palette in front of you, but with no plan as to what you’re going to do or when you’re going to do it. It’s like live-action painting, maybe. Programming, tweaking, endless mixing—that’s not something that appeals to us. Most of our early albums were recorded straight to stereo, and that’s it. So the mix had better be right—and in 99% of cases, it was! Job done. You just have to use your ears and be selfless in your contributions.

The other aspect of organic I was driving at was trying to describe the joy of music that evolves like nature does—at a slow pace, not always apparent what has changed, yet always moving along somehow.

Your music often evokes vast, otherworldly landscapes, as with ‘Galactic Furnace’ and its “turbulent cosmic fire.” What draws you to these themes?

Gary: I take you back to those night skies in our youth! It’s inspiring stuff, and the inspiration lasts a lifetime.

Duncan: An aversion to whiny, self-absorbed singer-songwriter trash! “Know thy place in the grand scheme of things.” Don’t know really. We do landscapes, not portraits, I guess would be the trite answer.

Steve: I guess the need within us as humans to express something bigger than ourselves or to acknowledge our place in the universe. That’s the feeling I get from it. It’s our way of saying that we appreciate where we are in time and acknowledging the vastness of space.

From your homage to Syd Barrett in ‘Rain Falls in Grey’ to your collaborations with Damo Suzuki, tell us more about these recordings.

Duncan: We have a number of favorite artists in common, though there is probably less overlap in our musical tastes than people might think. Damo Suzuki & the work of Can, for example, were on the periphery of Gary’s tastes, but when the call came, we knew what to do. Not our normal schtick, but also not a dumb Can replication like some of Damo’s other pickup bands. In fact, this was one of the occasions where our need to serve our own purposes coincided with the requirements of the day, which were to be recognizably R.M.I. but to support whatever Sprechgesang Damo came up with on the night. I think we pulled it off.

As for Syd… we had convened at the studio with, as it turned out, the drums & bass, as well as all of the electronic doodads. Then we got news that he’d died, and some sort of spell was cast over the proceedings, with the loose ideas & structures we’d brought to the studio suddenly taking on a new purpose: to honor the man whose brief career kickstarted the entire “contemplative improvisation” approach to music, and space rock in particular.

Over beers, we noted that “No Syd: no Hawkwind, no Hillage, no Gong…” and by extension, an effect on the musical landscape of later years too—would we have had Sonic Youth or Television without ‘Astronomy Domine’? Perhaps, perhaps not. But we turned these reflections into a sort of tribute, again without trying to replicate anything but bring our own musical stylings to the effort.

So, for me, I wasn’t about to start playing bass like Roger Waters necessarily, but like I would have done had I been in the presence of Barrett himself. There were nods on the album to the early Floyd sound, of course, but we also tried to suggest that “if it hadn’t been for Syd, we probably wouldn’t have had…” stuff like glissando guitar, or that terrifying tremolo racket at the start of the one piece that’s explicit in referencing him.

Here’s a version of it:

Steve: Syd Barrett—Syd was a massive influence on the music we call space rock, and the early Floyd is the prime example of what the Germans would later call Kosmische Musik. The Floyd started all of that, the abstract sounds, the hovering glacial keyboards, and when Syd passed, it happened to be shortly before a session we had booked.

As we would often do, we began the rehearsal just playing around on guitar, bass, and drums. The original jam for the title track evolved from spacey noises to Gary playing a chug-chug-chug theme, which I assumed was an attempt to begin a cover of ‘Astronomy Domine,’ so I cheerfully came in with an approximation of the Nick Mason drum intro, and before we knew it, we were fashioning a tribute to Syd that unfolded there and then.

We took the idea and ran with it thematically. The opening and closing pieces on the album were recorded one after the other. It’s amazing how quickly these things can happen sometimes. We also had a thing that we’d called “Syd” for ages before that anyway, so that went on it… we used a scary loop piece to evoke the bad trip element of Barrett’s life (‘Shut Up’), a more upbeat ‘Better Days,’ which is just our take on swinging London (as well as being an anagram of Syd Barrett… we don’t just throw these things together…). We covered aspects of later Floyd with Martin in the role of Dick Parry (‘Emissary/Legacy’)… just tried to make the album a survey of Syd’s influence.

Luckily, Steve at Cuneiform, although shocked at first, was happy to put it out. We are very proud of it, I must say.

Damo Suzuki—This came about by the tried-and-true method of me emailing Damo, offering our services, and thinking nothing more of it. A few months later, we had a message out of the blue to contact Jay Taylor at the Night and Day in Manchester, and that we were on for a gig. We prepared a version of ‘Mother Sky,’ which Damo immediately blew out of the water (“better to have no plan”). He was, of course, quite right. So we improvised the entire gig, and I must say, it is one of my favorite things I’ve ever been involved with.

It’s not easy to describe, but Damo definitely had something about him, a way of channeling musicians into doing something very special. We came up with four exceptional pieces, I think, and the secret, I think, is to get Damo working rhythmically. He shines when he’s being funky. He swings like mad. I’ve seen him too many times with guys playing free, and it gets pretty tiresome, but give him a good beat and watch him go! Luckily, we recorded all the instrumental parts on multitrack, and thankfully, the guy on the desk at the venue very diligently recorded the vocal feed, and we had a live recording second to none. I am eternally thankful to him.

Duncan and I grew up as huge Can fans, so it was amazing that first time. Gary said it was worth it to see the look on my face.

Having spanned over three decades, how do you maintain creative momentum?

Duncan: Like any relationship, conversation, or artistic enterprise, there is always something left to say. It’s somewhat of a necessity, like a bodily function, to express oneself through music. When one finds a comfortable situation in which to do this—the right space, the right equipment, like-minded associates—it’s easy. It’s natural. We have no outside pressures or duties—there’s no manager, no label boss saying “where’s the next album?” and we don’t do it for the money!

Steve: A lot of it has to do with thinking of different ways of doing things. Duncan will always be testing out the latest technology and tweaking the setup. I tend to stick with the tried and tested ways, though. We don’t feel constant pressure, and opportunities to get together tend to diminish as the years go by, but we always make the most of the time we do have by keeping an open mind and a blank canvas… and recording everything.

From intimate settings to grand festivals like NEARfest, what have been the most memorable or transformative moments in your live performance history?

Gary: NEARfest was an amazing experience, and we have good footage of that. I remember doing a rendition of ‘Rfig’ at the Orion venue in Baltimore… that was a good one. Our gigs in Philly for Chuck Van Zyl were good, we played there several times and got better each time, as I recall.

Duncan: Have you seen the movie Sophie’s Choice? I don’t think I can single one out like that—they’re all special in their own way. Even if they don’t all come off exactly as you’d want, there’s always something about a gig that redeems it. We might think it was a disaster, and then you listen to the recording, and it’s great. You could meet your future wife at a gig, or a fan who’s traveled internationally just to get your autograph. Or both of the Noble brothers buy you a pint in the same evening. (That’s one for the Britpop historians right there, along with Paul Kaye referring to us as “MFI”!) The last one is the most memorable, until the next one.

Steve: There are so many!

Each gig tends to have its own memories associated with it, as the circumstances change each time, but I’d have to say the first Jodrell Bank gig in 1996 was amazing because the music really worked—we were thrilled with it when we played it back. We had raided the BBC archives for the recordings of Jodrell Bank engineers bouncing radio signals off the moon: “This is Jodrell Bank calling… hello moon… hello moon.” We sampled them and triggered them during the main improvisation at just the right moment. I still get a shiver when I hear it.

NEARfest was great on so many levels. It was like a dream come true and just incredible to be a part of the whole weekend. It was quite intimidating being on such a big stage, but after another three or four like that, we would’ve been old hands at it.

The Gatherings series in Philly—where we have played five times—has always been special, thanks to the beautiful surroundings of the church, the light show, and, more than anything, the very appreciative audience. We love Philly!

Closer to home, our 2011 show at a church in Chorlton, Manchester, seems by some consensus to be a fan favorite. We got everything right that night, and that was the only concert appearance of the full Fender Rhodes setup. We had the whole evening to ourselves (greedy!), playing 45 minutes followed by another 90. Enough for even the most diehard fan.

(By the way, if you follow this link, you can hear me reminiscing about a few of our shows followed by extracts)

How does ‘Galactic Furnace’ represent where RMI is today creatively, and what directions or challenges do you see ahead?

Gary: In my case, staying healthy is a challenge! I’d also really like to try some arranged stuff again. We’ve often talked about an ‘RFIG II,’ and it feels like now would be a good time for that.

Duncan: It is, as are all of our recordings, a snapshot. Where we were at the time—geographically, of course, but also mentally—is baked into the album. There are practical matters that slow down our output, but it’s right to characterize these as challenges, not as problems or difficulties. We adapt. If it becomes overwhelmingly important to create a piece of music (and as I said before, the pressure to do this comes from within, like a bodily function!) and there’s no way for us to convene, we have a number of collaborative-working strategies.

Steve: It represents us as a band who are comfortable playing what we play, happy to build things over a decent length of time, and confident enough to not try and play to the crowd. It’s a very immersive work, as I realized when we held a listening party on Bandcamp and heard it all on near-field speakers and in one sitting. I was very pleased with it as a whole piece. We just continue to do our best with what we have at our disposal. Next, we’d possibly like to attempt a similar album to RFIG and have talked about it for so long it’s a bit of a running joke now!

You’ve collaborated with notable figures like Martin Archer and Cyndee Lee Rule. Are there any future collaborations or experiments you’re eager to pursue?

Duncan: We’ll have to see!

Steve: For the moment, I think we’re happy to keep it to the three of us. I think if we ever do ‘RFIG II,’ that would be when we would think about bringing in a few extra contributors. We’re lucky to know some very capable musicians.

Is anyone involved with any other project?

Gary: Not I.

Duncan: Steve is (Das Rad, Orchestra of the Upper Atmosphere, and so on); I am an international jet-setting broadcast professional with minimal spare time for this sort of thing, so I focus on one band only. I wish I had more time, played more bass, and did a solo album… Gary used to play in a dreadful covers band…

Steve: I am part of Orchestra of the Upper Atmosphere and most recently Das Rad. We’re making albums and getting them out there on Discus Music. I’m back in love with the acoustic drums again, and we recently completed a five-date tour of Northern England, which was fabulous, alongside Dave Sturt from Gong’s band This Celestial Engine. I’ve also been a temporary member of Mark Spybey’s Dead Voices On Air and recently played live with them in a double bill with RMI. Mark Spybey is the catalyst for where it all started 45 years ago, so it was an amazing full circle.

What are you currently listening to? Would love to hear about some of your latest favourite records…

Gary: I’ve just got that Hawkwind ‘Doremi’ set, so that’s my next listen. Still listening to them 40 years later! And I’ve got Gilmour’s new one— that’ll take some time to digest, I suspect.

Duncan: Dr. John, Luscious Jackson, stuff the kids play on KXLU, KALX, and so on. There’s not much I avoid, to be honest—even things that are calculated to reach a certain audience and separate them from their cash. Even those cynical works have an element of art still in them. You can get ideas, learn processes, from almost any noise.

Steve: I have a large collection… I tend to drill down very deep into stuff that I really like, hence the King Crimson boxed sets and Miles Davis anthologies. Lots of Krautrock, Folk, Prog, Jazz… I really should open my ears a bit more to new stuff though. Duncan put me onto this band Slift, who are pretty incredible. But then there’s a Folkie from up our neck of the woods in Teesside called Amelia Coburn, whose debut album I have played a lot this year. At the end of the day, despite all this cosmic nonsense, you can’t keep a good song down!

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours…

Gary: Peace! And be happy.

Duncan: Cheers!

Steve: Thank you, Klemen, and thanks to whoever is reading this!

Klemen Breznikar

Radio Massacre International Official Website / Facebook / X / Bandcamp

Cuneiform Record Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / Bandcamp / YouTube