Street Songs & Steel Guitars: An Interview with Cary Baker on Down on the Corner

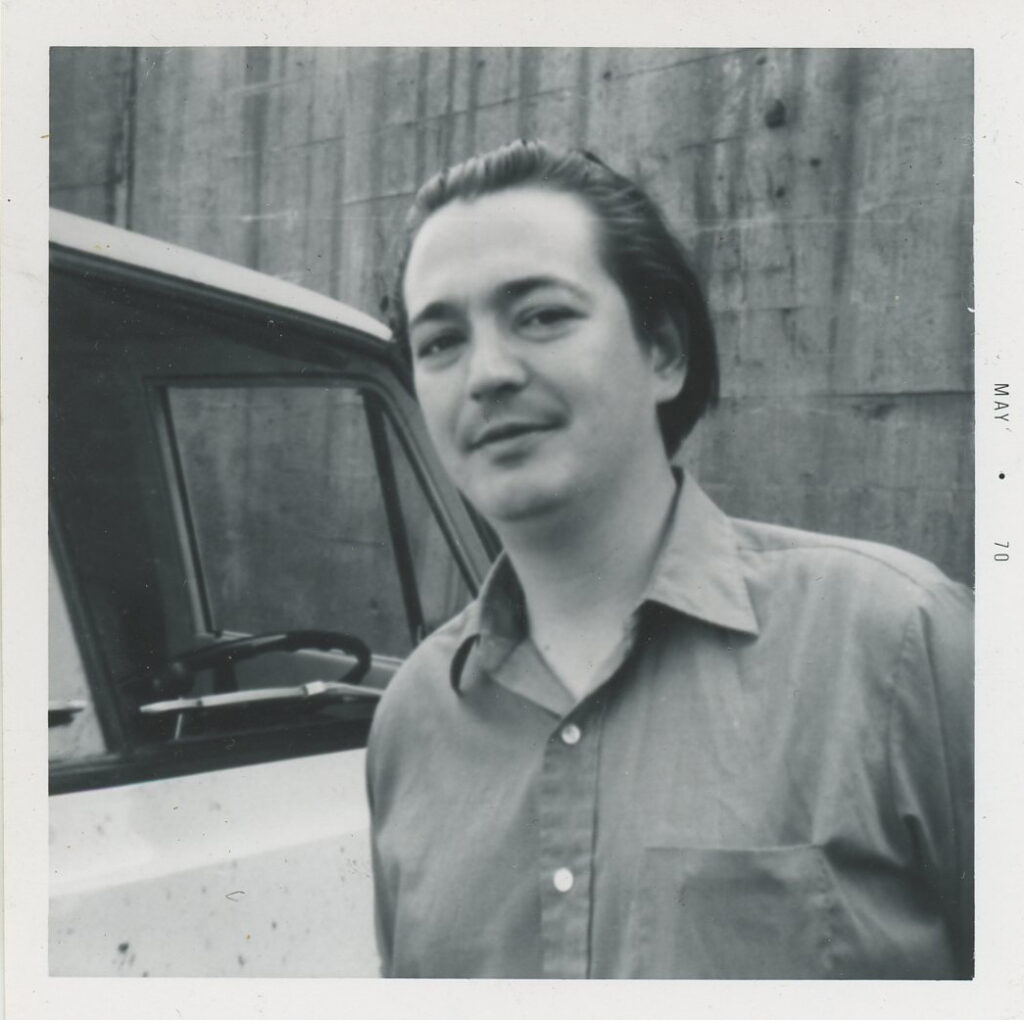

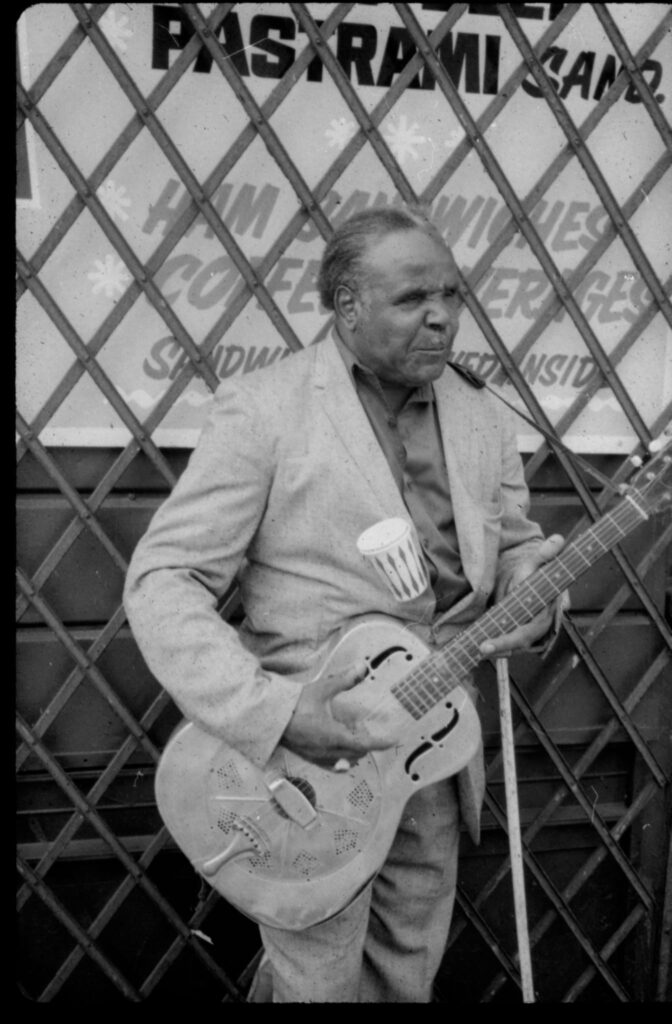

Cary Baker was just a suburban Chicago kid with ears wide open when his dad took him to Maxwell Street one day in 1970. There, on a cracked corner of Halsted, Blind Arvella Gray was singing ‘John Henry’ to a drifting crowd, and something clicked.

That one moment—resonator guitar sliding through city noise—sparked a lifelong obsession with street music and the people who make it. Fast forward a few decades and Baker’s done time on both sides of the music industry—writing for Creem, Trouser Press, and Goldmine before jumping into a 40-year run in music PR, working with R.E.M., Bonnie Raitt, and a laundry list of legends. Now he’s circled back with Down On The Corner, a deep, passionate dive into the wild world of buskers, from subway prophets to Venice Beach dreamers. Part oral history, part crate-digger’s diary, the book’s a love letter to performers who play for the moment, not the market. Baker’s back on the beat—and the streets have stories to tell.

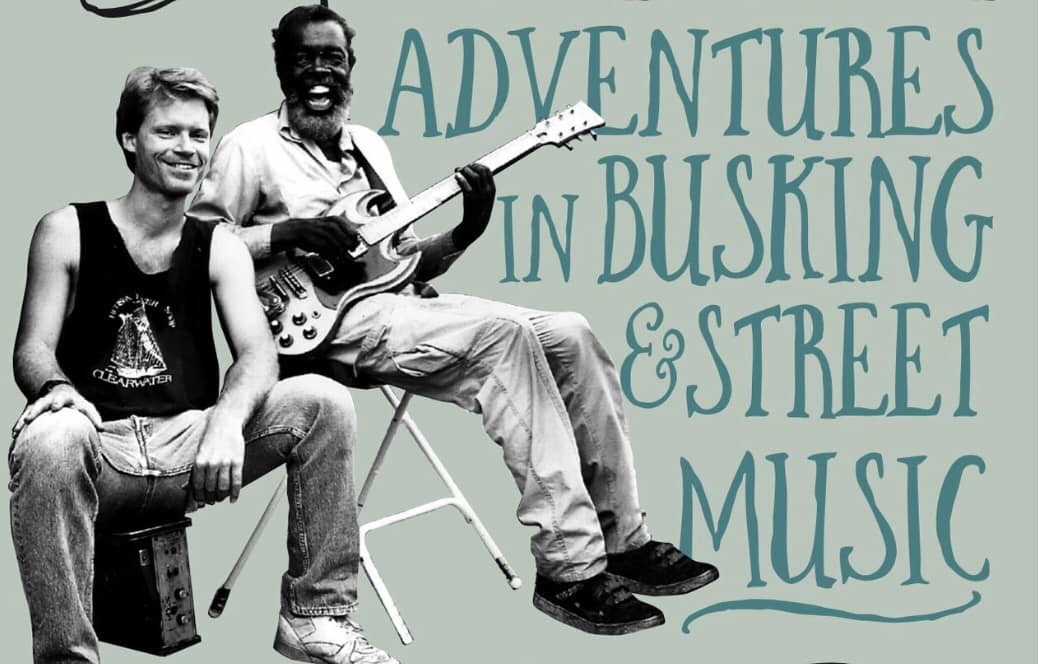

Down On The Corner is Baker’s tribute to the unsung legends of the sidewalk stage—street singers, subway pickers, and corner crooners from the 1920s to today. Mixing firsthand stories with deep-dig research, it captures the raw joy, hustle, and heartbreak of busking across America. A jukebox of voices that never needed a stage to be heard.

“Busking is the most primal expression of live music.”

You talk about your first musical moment being The Beatles on Ed Sullivan, but was there a sound before that—what were some other influences? Were your parents’ musical tastes a gift or a prison? Did they shape you, or did you have to escape them?

Cary Baker: Before the Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964, most of what I heard was classical music. Which is wonderful – and I respect my parents for their passion and knowledge of it – but it wasn’t so much my thing. That said, my mother was a violinist, and my father was something of a classical historian and musicologist. He claimed to own several versions of all the major compositions in his record collection. So I witnessed musical passion at an early age. It was a joy to go record shopping with my dad in later years – he’d be in the classical section, and me in the pop section. And invariably, he’d pick up the tab for both of us. I loved living in a house in which every wall contained record shelves. I later lived in such a house myself, and still do – despite having divested all my 78s, 45s, and many LPs and CDs. My parents supported my musical tastes and gave me the space to “follow the music.”

What’s the first record that actually scared you?

Scary music? Advancing the timeline to 1968, I remember hearing these two scary songs late at night on progressive, free-form FM radio: Dr. John’s ‘Gris-Gris’ and Clear Light’s version of Tom Paxton’s ‘Mr. Blue.’ Then there’s Howlin’ Wolf on songs like ‘Smokestack Lightning’ or ‘Evil.’ They reminded me of the “man behind the curtain” scene in The Wizard of Oz. Of course, so does the current state of Washington, DC.

That moment when you first heard Muddy Waters’ ‘Electric Mud’—was it like a lightning strike, or was it more of a slow burn that rewired your DNA?

I first heard Muddy Waters – I’d heard of him, but hadn’t knowingly heard him – on WGLD or WDAI, one of Chicago’s two underground FM stations. The song was the electrified version of ‘I Just Want to Make Love to You’ featuring Pete Cosey’s guitar riff. I immediately went out and bought ‘Electric Mud’ – which has received its share of critical scorn over the years, and remains scorned to this day. I still get into arguments over the album with blues purists. Producer Marshall Chess had intended to snare rock ’n’ roll ears with that LP, and its mojo worked on me. And when I noticed Chess Records was based in Chicago, look out! My future was formed in that moment. I started buying Chess records and other blues records in droves, and toured the Chess Records studio and office, thanks to a kind gentleman named Loren Coleman, whom I’ve never been able to find. He was Chess’ public relations director. If he’s still alive, I want to thank him! When I soon discovered the Jazz Record Mart – home of Delmark Records – my knowledge and appreciation of blues (and jazz too) kicked into a higher gear.

The blues had already been repackaged by rock bands by the time you got into it. Were you aware of that, or did it hit you later?

I thanked – and still thank – all the white rock bands who played blues with authenticity… Paul Butterfield, Canned Heat, Blues Project, Mayall, Cream, the Yardbirds, Jeff Beck… I began to notice common threads, like the ubiquitous songwriter credit Willie Dixon. And I was delighted when a lot of the names were in the Chicago white pages phone book. I used to peruse the phone book for hours, and actually called some of these people. And while bemused to hear from a white teenager who’d cold-called them, they actually talked to me. I also used to read the Yellow Pages – the commercial phone book – especially under the headings of Phonograph Record Manufacturers. That’s when I realized that not only was Chess based in Chicago, but so were Mercury, Alligator, Flying Fish, Brunswick, Dakar, Curtom, Dunwich, Mercury, USA, One-derful, Twinight, Bamboo/Mr. Chand, C.J./Colt/Firma, Bea & Baby, Atomic H, Sentar… there were so many small labels in the big city. And Chicago had a thriving Record Row (1300 to 2300 S. Michigan Ave.) where many of these labels operated or were distributed.

Did you ever feel like an interloper in the blues world, or did the music claim you as much as you claimed it?

Actually, I was immediately welcomed into the club, despite my age. No qualifiers. The only forbidden scene was Chicago’s blues bars. One had to be 21 years of age to enter. I was 14 or 15. But I hung on every story from Bob Koester, Bruce Iglauer, Wesley Race, and others about those establishments.

What made you grab the reins and start Blue Flame instead of just reading about music? A pure necessity?

To tell you the truth, I forget why I started Blue Flame. I just sort of did it without a lot of forethought. I wasn’t yet a journalist and had never really written, and knew nothing of publishing, even at a fanzine level. In fact, I’d never heard the word “fanzine” until a bit later via Who Put the Bomp! fanzine. It was amazing to me that there were so many others. And by then, I was circling back to rock ’n’ roll as well as blues, and just ahead of the paradigm-shifting arrival of punk and new wave. I thought nothing of seguéing from a Little Walter 45 to Iggy & the Stooges’ ‘Raw Power,’ or from Syl Johnson to Lou Reed.

The act of printing, schlepping, and mailing… I’m certain that DIY approach has something special… labor of love kind of feeling… it’s hard to put into words. Do you agree?

I was a sub-par high school student thanks to all my extracurricular activities. But I was finding purpose, and that doing this would lead – somehow – to my future. And it did. I lovingly schlepped home new issues of Blue Flame, printed at Sir Speedy Printers in Evanston, in a suitcase via the municipal bus line. And then I’d get them home, collate and staple them myself, and mail them to a subscriber base that included authors Nick Tosches and Peter Guralnick, journalist Dan Forte, A&R man Joe McEwen, and other notables – all over the world. U.K… Sweden… Germany… Japan… Australia… It was my first connection to a larger world.

Blind Arvella Gray: What did his voice tell you that words couldn’t?

You’re right to ask – there was a special quality to his voice. It wasn’t just the steel-on-steel slide guitar on a resonator guitar. Nor just the endless version of “John Henry.” But there was hurt, pain, hard labor, debilitating injury, struggle — yet an unmistakable sense of courage in his voice — and kindness too. I was happy to visit his apartment at 49th & Dorchester on Chicago’s South Side to see that this blind street singer lived in relative comfort. When I found myself with some buddies in the college party town of Madison, Wisconsin, and saw that Arvella was playing, we offered to drive him home to Chicago in exchange for couches and floors on which to crash. When Arvella woke us up at 5:30 a.m. and wanted to start the drive to Chicago (given our druthers and the late hour, we would have slept ’til 9 a.m.!), that moment converted him from blues legend to human being. He also navigated us off Chicago’s Dan Ryan Expressway onto 47th Street and to his door as if he could somehow see where we were going. That still astounds me.

The Chicago Reader was your first big break. Would love to hear more about that.

I sent an unsolicited typed manuscript — my interview with Arvella Gray — to the Reader, and to my delight, it was printed! They even sent me a check — maybe $25 — which was appreciated, of course, but the real payday was the byline. In time, I was writing more for them — and not just about blues, but about rock. I later began compiling their music calendar each week, hand-delivered on 3×5 file cards, for a whopping $10 per week. That seemed like a lot of money back then.

Cheap Trick… what made them different from the sea of Midwestern bar bands clawing for the same scraps?

My college roommate at NIU, who was more of a rock ‘n’ roll partier than I was, came home one night at midnight and woke me up, exclaiming: “Dude! I just saw this band that reminds me of The Who, The Kinks and The Move… They’re called Cheap Trick, and you need to see them next time they play!” So I did. And wow! $5 cover, three sets, that lineup, those songs, that logo. I hadn’t ever seen an unsigned band so fully formed in its repertoire and image — especially from the Midwest, which had mostly mainstream bands: REO Speedwagon, Styx, Head East. Seeing Cheap Trick at the UpRising Tavern in downtown DeKalb, Ill. was a revelation. I followed them everywhere I could. I interviewed them 10 or 15 times, for several magazine stories — many of them cover stories. I was even junketed to other cities — Detroit and Fargo, North Dakota — when magazines needed fresh interviews immediately. By then, I was an editor at Rockford’s weekly entertainment magazine, Lively Times. I remember visiting drummer Bun E. Carlos at his Rockford apartment, and he played DJ for me all afternoon, mainly with 45 RPM singles. He knew all the A-sides, and he knew all the B-sides. And I remember the polysyllabic way he pronounced cool: coooo-oooo-oool! And he’d say it often.

“I was very happy in print, and remain so.”

You walked away from radio. Print followed. Tell us about that period of time.

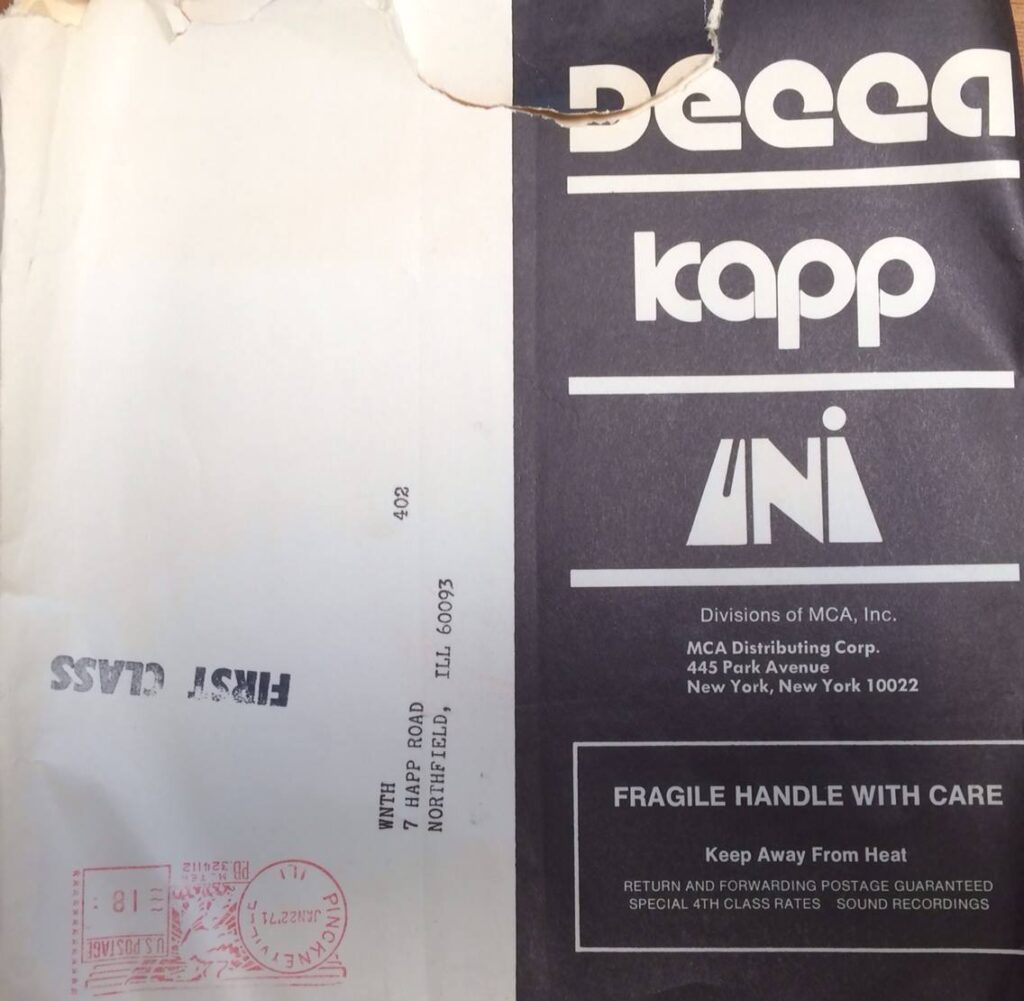

I had served as blues DJ, music director and public relations director of my high school radio station, WNTH-FM in Chicago’s north suburbs. That was an unbelievable amount of career focus for a 14-year-old! I catapulted that into an air shift at commercial free-form rock station WVVX-FM, and a friend and I brokered some time at WOJO-FM, which is nowadays Chicago’s Latino beacon. So when I entered college, I was given an evening air shift at WKDI-FM, the carrier-current radio station at Northern Illinois University. I don’t believe I dazzled them. And when I contracted mononucleosis — thanks to my first college girlfriend — I went home to Chicago to convalesce and was briefly hospitalized. By then, they’d replaced me on my Tuesday evening slot. They offered me a Tuesday afternoon instead, when students were in class. I was also the pop music critic at the college newspaper, The Northern Star. And print seemed to resonate with me more than radio. So I politely resigned from radio and never returned. I remained a fan, though, and watched with great interest the birth of Chicago’s free-form WXRT — which is where many of my fellow WKDI jocks ended up. I was very happy in print, and remain so.

What was the weirdest interaction you ever had as a music journalist?

There were many. One that comes to mind was one of my first interviews ever — the late Cub Koda of Brownsville Station. They were on a bill at Chicago’s Aragon Ballroom around 1972 with some band I was assigned to interview, so while backstage I did a spontaneous interview with Cub — without knowing anything about the band. I was 15 years old and just winging it. When asked to describe the band, Cub said: “We’re a beer-drinking, woman-f#cking rock ‘n’ roll band from the Motor City. We don’t got the blues!” I felt like that quote, brash as it was, was a gift to a young gonzo-inspired journalist, and I included it in the story. Well — surprise — Cub was a huge blues fan! I began to see articles and liner notes by him for many respected blues albums. Finally, six years later, I saw Cub again at Gaspars, a bar on Chicago’s North Side. I reintroduced my older, wiser self, and reminded him of that 1972 quote. He grinned and said, “Jeez, Cary, did you have to print that?” We had a good laugh.

There was the 1982 interview I did with neo-Tex-Mex artist Joe “King” Carrasco at my house, during which he went to my answering machine and dictated a new outgoing message: “Hi, this is Joe “King” Carrasco. Cary’s not home right now, so come steal his answering machine!” But that was more funny than weird.

There were many other weird interactions as well, of course, but none are specifically coming to mind.

You’ve worked both sides—writing about records and promoting them. Where does the real manipulation happen: in the press or behind the label’s closed doors?

During my 40 years as a music publicist for six labels and three PR firms – including two of my own – I never saw what I did as manipulation. I saw myself as the resident rock critic – the guy with the journalism degree at these labels. And having been a writer of at least moderate renown, journalists trusted me when I came calling. They were aware I had to push a few artists who weren’t necessarily my favorites, and for the most part, they worked with me even on those. But no, I always put my newsroom background upfront in my communications – from the press releases and bios to emails once the internet was underway. I saw many illiterate press releases and pitch letters in my time. I won’t name names. So I always kept my context as a journalist front and center in my approach. And when I went out to lunch with writers, it was never a pitch-a-thon; we’d talk about current music on and off my labels, music history, record collecting, who we’d seen onstage, etc. I made it an effort to stay informed about the larger scope of pop music. I wasn’t alone in coming from journalism into PR. But I was able to get to the angle of the story and how it might work on such-and-such newspaper or magazine. So I think a lot of writers paid attention as a result. Of course, my stint at I.R.S. Records, with a roster full of critical darlings like R.E.M., hurt none.

When punk exploded, did it feel like the second coming of the blues… primal, something straight from the gut?

I don’t see punk as the second coming of blues per se. But in my own case, there were some striking parallels. I became aware of blues, of course, in 1958, thanks in part to ‘Electric Mud.’ Punk, of course, is rooted in garage-rock, which in turn is rooted in blues. But for me, discovering the blues around 1968 made me want to hear and buy every record I could get my hands on. By publishing my blues fanzine, Blue Flame, I became aware of Greg Shaw’s rock fanzine, Who Put the Bomp!, which I read with great interest. Shaw championed garage bands of the Nuggets era and foresaw the revival of that aesthetic as far back as 1973–74, starting with the MC5 and the Stooges, Bowie and Reed, and the Flamin’ Groovies. Before you knew it, that movement had galvanized into punk and new wave. Just as I’d taken sojourns into Chicago’s South Side to hear blues, I made a journey in August 1977 (August 16, 1977, as news of Elvis’ passing hit newspapers while I was on the Amtrak train) to New York to visit CBGB and met the editors of Trouser Press, Kicks, and NY Rocker. It was a very exciting time, and I was able to watch it gather steam. For a while, I bought every picture-sleeve 45 RPM new release I could get my hands on. I’d been the same way with blues nine years prior.

What was the first real punk show you saw, and did it shake you to your core or just confirm everything you already knew?

I attended a few Chicago punk shows at La Mere Vipere, the city’s first punk club. But I never felt at home in that scene. So in reality, my journey to CBGB in August 1977 – where I saw the Dead Boys and Johnny Thunder – might as well qualify as my first punk show. I made a similar trip to L.A. later that year. On graduation from college in upstate Illinois and returning to the city of Chicago proper, I promptly became a fixture on the city’s punk and new wave scene, out at least four nights a week at clubs like Metro, Tuts, Cubby Bear, Exit, Gaspars, Huey’s, and more.

You were ahead of the curve on alt-country. What did you hear in it that others missed?

At first, I related to country the way I related to blues. I was fascinated by its pioneers: Hank Williams, Ernest Tubb, Patsy Cline. Right out of college, I was offered a job at a Chicago label with a Nashville A&R office – Ovation Records – which had a thriving country roster with gold-certified, Grammy Award–winning father/daughter duo The Kendalls.

You saw Disco Demolition up close. Was it a righteous cultural movement, or just a bunch of suburban white dudes freaking out because the mainstream left them behind?

I didn’t actually attend WLUP-FM DJ Steve Dahl’s Disco Demolition at Chicago’s Comiskey Park. I was pro-rock, of course, but not altogether anti-disco. I’d met Steve Dahl at Creem magazine’s office in the Detroit suburb around 1977. After the demolition, the label I worked for – Ovation Records – signed Steve to a one-single deal. The song, ‘Do You Think I’m Disco,’ was rush-released and climbed to #58 on the Billboard Hot 100 – which was boundlessly exciting to a 24-year-old who was working his first label gig. In retrospect, I now feel Disco Demolition carried with it some racist and anti-LGBTQ+ implications. So while it was exciting to watch a record skyrocket its way up the Billboard chart, I feel no enduring pride in having been associated with that project. Ovation, of course, also had legit country hits, and that, too, was exciting.

As a completely obsessed fan of Canned Heat, I stumbled across your social media post discussing meeting Bob Hite and his brother Richard. Could you share some further words about Hite and how you originally got to know him… what he was like, etc.? (Fanboy talking here.)

Bob “The Bear” Hite and I became unlikely friends in the early ’70s. Bob and his brother Richard subscribed to my blues fanzine, Blue Flame. And I subscribed to their ‘zine, R&B Magazine (as in Richard & Bob). When they came to Chicago around 1972 to play the Aragon Ballroom, I took the two avowed rare record collectors crate-digging at Maxwell Street Market (including the Maxwell Radio & Record Store, home of the Ora-Nelle label) and various Salvation Army locations.

In turn, Bob invited me to look him up if I ever made it to the West Coast. So in 1977 or so, I made my maiden voyage to L.A. I visited him at his 1920s Spanish-style casa in Topanga, which, predictably, was wall-to-wall blues 78s, 45s, and LPs.

We started listening, and Bob broke out the weed — not the regulated cannabis edibles you can buy at dispensaries nowadays, but gnarly misdemeanor street pot. His announcement: “It takes a lot to get a big guy like ME high!” Me? Not so much. Anyway, we became so immersed in obscure 78 RPM blues records of the ’40s and ’50s (and weed) that I wasn’t entirely sure I ever wanted to return to the present day.

A few hours later, Bob went to his freezer and retrieved a large vat of ice cream, the sugar rush from which helped me to contemplate my drive down serpentine Topanga Canyon Blvd. to the SFV where I was staying. And thus I began my journey across the hills — and back to the late ’70s.

No other Bear stories to relate. Sadly, I never did see him after that night in 1977. He transitioned in 1981. I arrived in L.A. as a resident in 1984.

I’m very excited to discuss your recently published book. How would you describe Down on the Corner to someone who has never heard of it? What inspired you to write it?

When I set out to write a book, I was initially going to write about music of the California desert — from Frank Sinatra to Elvis Presley to Captain Beefheart to Gram Parsons to Dick Dale to Eric Burdon to Queens of the Stone Age. But I found that there was already a definitive book about Joshua Tree (Songs of Joshua Tree, highly recommended). And I soon met a reporter in Palm Springs who had 40 years’ worth of interviews with Rat Packers, Sonny Bono, and the grunge scene that begat Kyuss. So I decided to change course. I began to call managers of legacy artists, starting with the estate manager of late Venice Boardwalk busker Ted Hawkins. Indeed, they were keen to get a biography written about Ted. When I brought that to a publisher, the publisher asked: “Who is Ted Hawkins?” I replied that he’s a busker… a street singer. There was a pause. Then the publisher said: “Well, what about a book about buskers… street singers… plural?” So that became the book. It’s not an encyclopedia of busking — it’s really just a collection of busking stories from the street musicians themselves.

Thankfully, I’d chanced upon many buskers in my time: the Maxwell Street blues singers in Chicago. The Violent Femmes in Milwaukee. And then Ted Hawkins and Harry Perry in Venice when I first moved to L.A. Mary Lou Lord on Austin’s East 6th Street during South by Southwest. Artists in New Orleans’ French Quarter. So that became the book. It took me a year of interviews and research, and I developed a love for buskers the more I delved in.

For now, everything I have to say about buskers is in that book. But I haven’t ruled out an eventual Volume 2, and have many interviews saved up for when and if that time comes.

I only wish my dad, who took me to Maxwell Street when I was 16 — never expecting to encounter the music we heard — were around to read the book! I’m thankful that my mother was able to read it.

What do you hope readers take away from this book, beyond just learning about the history of busking?

In brief: Respect and support buskers. In this day of being able to order anything from Amazon, buskers are keeping the downtowns of cities alive, and giving us additional incentive to shop at brick-and-mortar stores. It’s the most primal expression of live music. And I like that!

I hope this has been as much fun for you as it was for me. What’s next for you? Last words are yours.

What’s next for me? Another book. I can’t get too specific, as it’s a longer road than Down on the Corner — a biography of a musician who’s lived a long life (and is still living it!). More on that next year. And maybe some articles. Apart from that, enjoying a little spare time on my hands. And trying to continue to make even a small difference. I feel I helped some recording artists get their music out there. After 40 years in artist support and artist development, it’s fun to BE the artist for a moment.

Klemen Breznikar

Cary Baker Instagram

Down on the Corner: Adventures in Busking and Street Music by Cary Baker