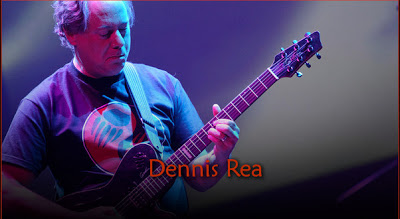

Dennis Rea Interview

What are some of the early influences?

From a very early age I always felt attracted to ‘weird’ music – weird in the sense of being unconventional, or perhaps a bit eerie or dreamlike. I was fortunate to grow up during the psychedelic ‘60s, a time of unparalleled experimentation in popular music, when it was commonplace to hear extremely odd tunes like Lee Hazlewood and Nancy Sinatra’s “Some Velvet Morning” or any number of lysergic-laced Summer of Love nuggets on mainstream radio – it was mold spores like those that bent my budding musical consciousness. But I also count many of the ‘classic’ rock bands of the time as important influences – Hendrix, the Who, Zeppelin, the Allman Brothers, and so on.

The person who had the greatest influence on my developing musical tastes as a youth was my much older brother Woody, who had an encyclopedic knowledge of jazz and other contemporary music (and whose son Michael went on to play guitar with prog-metal legends Queensryche). Woody supplied me with a steady stream of quality records in my early years, giving me a bit of a head start on my peers. Chance encounters with the music of such mavericks as John Cage and Gyorgy Ligeti were also key to shaping my musical thinking. Later, the entire ECM catalog, pioneering jazz-rock bands such as the Mahavishnu Orchestra, and the jazz avant-garde of the 1960s were also hugely influential.

You started in a band called Zuir.

Zuir actually grew out of an earlier band called Atmosphere that had a single public performance, but it was in Zuir that I felt my ideas and musical personality really started to take shape. I formed the band with two close friends from my hometown of Utica, New York – bassist Norm Peach and drummer Daniel Zongrone – when we were still in our mid-teens. By this time (around 1972) we had all become rabid fans of the first wave of (mostly British) progressive rock bands – Crimson, Floyd, Gentle Giant, Soft Machine, Curved Air, the usual suspects – and did our best to emulate them, not so much aping their specific musical styles but rather taking inspiration from their commitment to instrumental excellence and spirit of open-minded inquiry. I was feeling confined by the narrowly restrictive format of the dominant blues-rock of the time, and started writing lengthy pieces that explored unusual scales, harmonies, and time signatures. In hindsight (hindhearing?) our efforts sound very amateurish, but Zuir was nevertheless an important first step on the path that brought me to where I am today.

Zuir was completely out of place in a city that was mostly in the grip of Southern roadhouse rock, so we had to create our own opportunities, renting small halls and utilizing alternative venues for the few shows we played. Although we enjoyed a small but devoted fan base in Utica, we yearned to expand our horizons and jumped at my brother’s offer to manage the band if we were willing to move all the way out to Seattle where he lived. So we pooled our scant resources, bought a badly damaged truck, and relocated to Seattle at the tender age of 18, only to find that audiences there were even less receptive to our weird music than they’d been in Utica. We accomplished little musically in Seattle and ended up back in Utica a short time later, but it was a very important rite of passage for all of us and laid the foundation for my future activities as a Seattle-based musician.

Earthstar was your first band that released four albums between 1978 and 1983. Legendary Klaus Schulze produced some of the albums.

Earthstar was the brainchild of keyboardist and composer Craig Wuest, a fellow member of the tiny progressive music minority in Utica who had forged a friendship and musical alliance with Zuir. Craig was one of the earliest people in Utica to own a synthesizer and various other electric keyboards and was the first person to introduce me to the kosmische musik scene then thriving in Germany – Tangerine Dream, Cluster, Popol Vuh, Kraftwerk, Amon Duul, etc. At first, Earthstar was basically Craig’s solo project, but as time passed he enlisted various collaborators to flesh out his vision. The first Earthstar album, the long out-of-print LP Salterbarty Tales, was released by Nashville-based Moontower Records in 1978 and marked my first appearance on record.

Meanwhile, Craig had begun corresponding with one of his favorite electronic musicians, Klaus Schulze, who was impressed with the demos Craig had sent him and encouraged Craig to relocate to Germany, where ears were somewhat more receptive to that sort of music than in retro-rock Utica. Craig decided to try his luck abroad and settled in Hambühren, near Schulze’s base of operations in northern Germany, just as Klaus was launching his Innovative Communications (IC) label. Klaus proposed that Craig record a new Earthstar album for IC, and Craig set about recording tracks at some of Germany’s finest studios. After a time he decided to recruit some of his old hometown collaborators to contribute to the project, so I traveled to Hambühren to take part in the sessions; in all, I spent about a half-year there over the course of two stays.

For various reasons no Earthstar album ever materialized on IC, but the band was instead signed by Sky Records, one of the flagship ‘krautrock’ labels of the day, and released three LPs, one of which, French Skyline, was produced by Schulze. I made contributions to two of these releases, more as a sideman than a core player in what was essentially Craig’s project. But there is also a ‘lost’ Earthstar album, Sleeper the Nightlifer (also produced by Schulze), which was a much more collaborative effort and quite a departure from the sort of flowing space music for which Earthstar is typically known. It’s not likely that Sleeper will ever see the light of day, though. In retrospect I’m very proud of Craig and Earthstar for being probably the only U.S. group to have participated, however marginally, in the German kosmische musik scene during its heyday, but from this distance I have mixed feelings about the music itself – some of it stands the test of time very well, some not so well.

Savant followed and then in the 90s you were member of Land and later on collaborated with Eric Apoe and They, Stackpole, and Ting Bu Dong.

After Zuir and Earthstar evaporated I was somewhat adrift in my musical life for a time. My first collaboration of any consequence during that period was with electronic composer K. Leimer in his Seattle-based project Savant, which resulted in the 1982 LP The Neo-Realist (At Risk). Like Brian Eno, Leimer was interested in the generative possibilities of self-governing systems fed with limited musical inputs. It was a sort of collage sensibility that, in the era just prior to the introduction of digital recording techniques, involved a lot painstaking physical cutting and splicing of tape. Downbeat reviewed the record together with Byrne and Eno’s My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and I feel the comparison is apt.

After this second stint in Seattle I moved to New York City for three years, and though my musical activities there were largely confined to the underground, being surrounded by all the groundbreaking music then exploding in Downtown Manhattan, especially musicians situated along the Laswell-Zorn axis and in the modern jazz scene, was crucial to my developing musicianship.

It was only after I moved back to Seattle in 1986 that I started performing in public more regularly, first with an avant-funk unit named Color Anxiety and subsequently with more aggregations than I can remember. It was at this time that I first began to immerse myself in the world of free improvisation, which led to my co-producing the long-running, internationally recognized Seattle Improvised Music Festival for many years.

As you point out, I’ve been blessed to have collaborated with so many supremely talented musicians over the years. In some cases these are relationships that developed over long periods of time, while in others it was simply a matter of being in the right place at the right time. I find that working in the areas of jazz and free improvisation in particular fosters numerous, ever-shifting collaborations. All of these relationships have provided musical inputs that are an integral part of who I am as a musician.

Shadow in Dreams was your first solo album.

In 1987 I met my future wife Anne, who had recently graduated from the University of Washington with a degree in China Studies. Anne soon secured a teaching post in China and then arranged a job there for me as well, so in early 1989 I joined her in the city of Chengdu in Sichuan Province for what I expected to be a year of teaching English. Operating under the assumption that China was a repressive authoritarian state, I expected that there would be little if any opportunity for me to perform my type of music there, so no one was more surprised than me when I found myself on a wild musical rollercoaster ride, playing concerts in sports arenas with a Chinese pop star, collaborating with some of the founding figures of Chinese rock, and recording a solo album, Shadow in Dreams, for the state-owned China Record Company that sold an amazing (for me at least) 40,000 units.

Shadow in Dreams came about when I was approached by an unusually open-minded producer at China Records who had seen me perform. He invited me to make a solo record for the label, and of course I jumped at the chance – it’s not every day that a progressive musician is handed an opportunity to break new ground in an exotic communist country. But when it came down to planning the material, the producer suggested that I model it after the wildly successful easy-listening records made by French schlockmeister pianist Richard Clayderman that were then all the rage in China. It appeared that the producer had completely misread my musical personality and was really looking for something more crowd-friendly. I was completely unwilling to compromise my sensibilities, so I told the label that I probably wasn’t their guy. But the producer kept working on me, stressing the need to include at least one piece that was familiar to the Chinese audience, and the compromise we reached was that I would include a version of Beethoven’s “Fur Elise,” a ubiquitous piece of muzak in China at the time. I agreed on the condition that I would be free to arrange the tune however I liked, and with the help of various effects pedals and physical preparations managed to make it the strangest track on the record, much to the label’s chagrin.

Shadow in Dreams was recorded under rather primitive conditions (balky equipment, numerous power outages) at the label’s Chengdu studio and involved a lot of overdubbing, as there were few local musicians who could relate to my music. The material ranged from jazz ballads to adapted Chinese folk tunes to pieces that were vaguely prog-rock. I did the best I could under the circumstances, and am proud of the accomplishment but not so much the music itself, though it has its moments.

That and many other wacky adventures are recounted in my book Live at the Forbidden City: Musical Encounters in China and Taiwan, which also provides some background on the emergent Chinese rock, jazz, and experimental music scenes.

Can you share some details how Moraine was formed?

Moraine has come a long way since its origins as a casual improvising duo made up of myself and cellist Ruth Davidson. Eventually we each brought some of our tunes to the project and the focus gradually shifted from improvisation to composed pieces. To bring out the potential of the compositions, we expanded the group over time to include violin (Alicia DeJoie), drums (Jay Jaskot), and bass (currently Kevin Millard). When Ruth and Jay left Seattle for the East Coast a couple of years later, they were replaced by James DeJoie on woodwinds and Stephen Cavit on drums. With the change in personnel, Moraine’s approach evolved from the chamber-like ‘string quartet plus drums’ format heard on Manifest Density to the much more forceful sound captured on our new CD Metamorphic Rock: Live at NEARfest.

It’s kind of a fusion of very different styles of music.

Moraine’s music is the sum of all its members’ widely varying musical interests and experiences, which span all kinds of rock music, jazz, avant-garde classical and experimental music, various world musics, noise, even country. We feel no compunction to adhere to any specific stylistic parameters, and revel in exploring any musical direction that suits our instrumentation and musical personalities. Despite this stylistic variety, I think we’ve reached a point where whatever style we choose to play, the result sounds like Moraine.

We never considered ourselves a ‘prog rock’ band but simply a wide-ranging electric instrumental unit, as likely to play jazz or Chinese folk music as anything resembling prog. Indeed, I’m the only member of the band who has a background in and much familiarity with progressive rock. It was only after we hooked up with MoonJune Records that we found ourselves labeled ‘prog’ by listeners from that world. Our attitude is that if the progressive community wants to embrace us, we’re very happy with that, but our music goes well beyond that genre description.

I think listeners will agree that our new CD, Metamorphic Rock: Live at NEARfest, is a huge leap forward from Manifest Density. We had the incredible privilege of being invited to play the major progressive music festival NEARfest last year, quite an honor for a relatively new, mostly unknown band. Fortunately we proved to be up to the challenge and turned in one of our finest sets ever, with a lot of energy and inspired soloing. The track list includes new pieces and some selections from Manifest Density, which show just how much the band has grown since the previous CD was recorded. We hope your readers will take a chance on it, and trust that they won’t be disappointed.

Iron Kim Style was your next project after Moraine’s Manifest Density. This is some intensive listening! It’s one of the most interesting jazz-rock albums I’ve heard lately. Were you inspired by Miles Davis’ electric era?

Many listeners have noted similarities to Miles’ electric period, no doubt due to the presence of trumpet. While we weren’t consciously emulating the great man’s music, we are of course thrilled to be mentioned in the same breath. The key thing to know about Iron Kim Style – and this seems to have escaped many reviewers – is that the music on the disc is 100-percent improvised, even though it may not sound that way in places. Unlike the more ideologically driven free improvisers who pathologically avoid playing in a fixed key or settling into periodic rhythms, we embrace grooves and harmonic progressions as keenly as we do abstraction and noise.

Iron Kim Style was never a ‘band’ per se, and we’re very surprised and pleased at the positive responses the CD generated, but we have no explicit future agenda. The group is dormant at the moment but could rear its beastly head again anytime the spirit moves us.

Your latest solo album is called Views from Chicheng Precipice.

Together with my book Live at the Forbidden City, Views from Chicheng Precipice is one of the two end products of my years living in China and Taiwan and is a way of repaying my debt to that musical culture. Unlike most expatriates I encountered during my stay in Asia, who avoided their host countries’ traditional music as if it were poison ivy, I developed a great enthusiasm for the music of East Asia and early on started adapting selected traditional pieces for my instrument. For Views, I had the good fortune to enlist some of the finest instrumentalists in all the Pacific Northwest, whose amazing contributions enriched the music far beyond my most optimistic hopes. The idea was to approach the source material with respect while incorporating the full range of my musical influences, from free jazz to electronics, highlighting intriguing similarities between the two cultures.

What are some of your future plans?

Happily, Moraine’s appearance at NEARfest, exposure to a worldwide community of like-minded listeners through MoonJune, and recent U.S. East Coast tour are opening doors to a lot of exciting opportunities for the band, including the possibility of performing in Brazil, Korea, and Europe within the next year or so. And we’ve already assembled nearly enough material for a third CD, which will be a studio effort. I see plenty of potential for Moraine for years to come.

Apart from Moraine and the currently inactive Iron Kim Style, I’m still involved in the electronically processed kalimba trio Tempered Steel; we have a recording in the can that we’d like to get out soon. I continue to work in various improvising situations including a guitar trio with Brian Heaney (Ask the Ages, Sunship) and Stephen Parris (Monktail Creative Music Concern). I contributed to forthcoming CDs by Jeff Greinke and the Jim Cutler Jazz Orchestra that should appear soon. An improvised trio outing with saxophonist Wally Shoup and drummer Tom Zgonc will likely see release in the coming year. And Leonardo Pavkovic of MoonJune has suggested a ‘power trio’ made up of myself, former Moraine and Iron Kim Style drummer Jay Jaskot, and Clint Bahr, bassist for Tripod, who released a disc on MoonJune a few years back. It’s a very enticing prospect and we’ll likely do some sessions this fall in NYC for a hopeful MoonJune release. Meanwhile, I’ve been co-presenting two monthly progressive/jazz-rock concert series at small Seattle venues, showcasing the abundance of remarkable local talent that, as in most places, seldom get their due in the press or among various trendy scenes.

What about nonmusical inspirations?

For me, nonmusical inspirations have always been at least as important as musical ones. My single greatest inspiration is the natural world – landscapes, terrain, geology, wildlife… Note that the name Moraine is itself a geological term denoting the debris deposited by glaciers. Ruth Davidson came up with name, but as a bit of a mountaineer, it felt perfect to me.

Recent musical inspirations include numerous Norwegian musicians such as Arve Hendriksen, Trygve Seim, Jon Balke, and Christian Wallumrod, who all record for ECM – I think some of the most interesting music in the world nowadays is coming from Norway, and there’s an incredible amount of variety as well. I’ve also been rather obsessed with Scott Walker’s solo albums of the late 60s – staggering creativity. I’ve been listening to a lot of ‘60s and ‘70s British jazz records that feature vocalist Norma Winstone. Jon Hassell’s Last Night the Moon Came Dropping Its Clothes in the Street has been exerting a strange, lasting fascination on me. Sunn O)))’s recent Monoliths and Dimensions really blew my mind. And I continue to be amazed at the strange contemporary ethnic artifacts unearthed by the fabulous Seattle-based Sublime Frequencies label. As for live performances, I recently had the dream of a lifetime fulfilled when I saw the great Milton Nascimento in a relatively intimate venue here in Seattle – his performance brought me to tears.

Would you like to add something else, perhaps?

I’d just like to offer heartfelt thanks from myself and the members of Moraine and my other projects for your kind interest in our music, and for giving me this chance to share my thoughts with your readers. One of the best things about hooking up with MoonJune is that it has introduced us to a wonderful community of like-minded listeners worldwide, and we all need allies in times like these. Hope to play somewhere near you soon!

– Klemen Breznikar

It's an excellent interview.

Cassy from Acoustic Guitar Online