Mick Softley And His ‘Songs For Swinging Survivors’

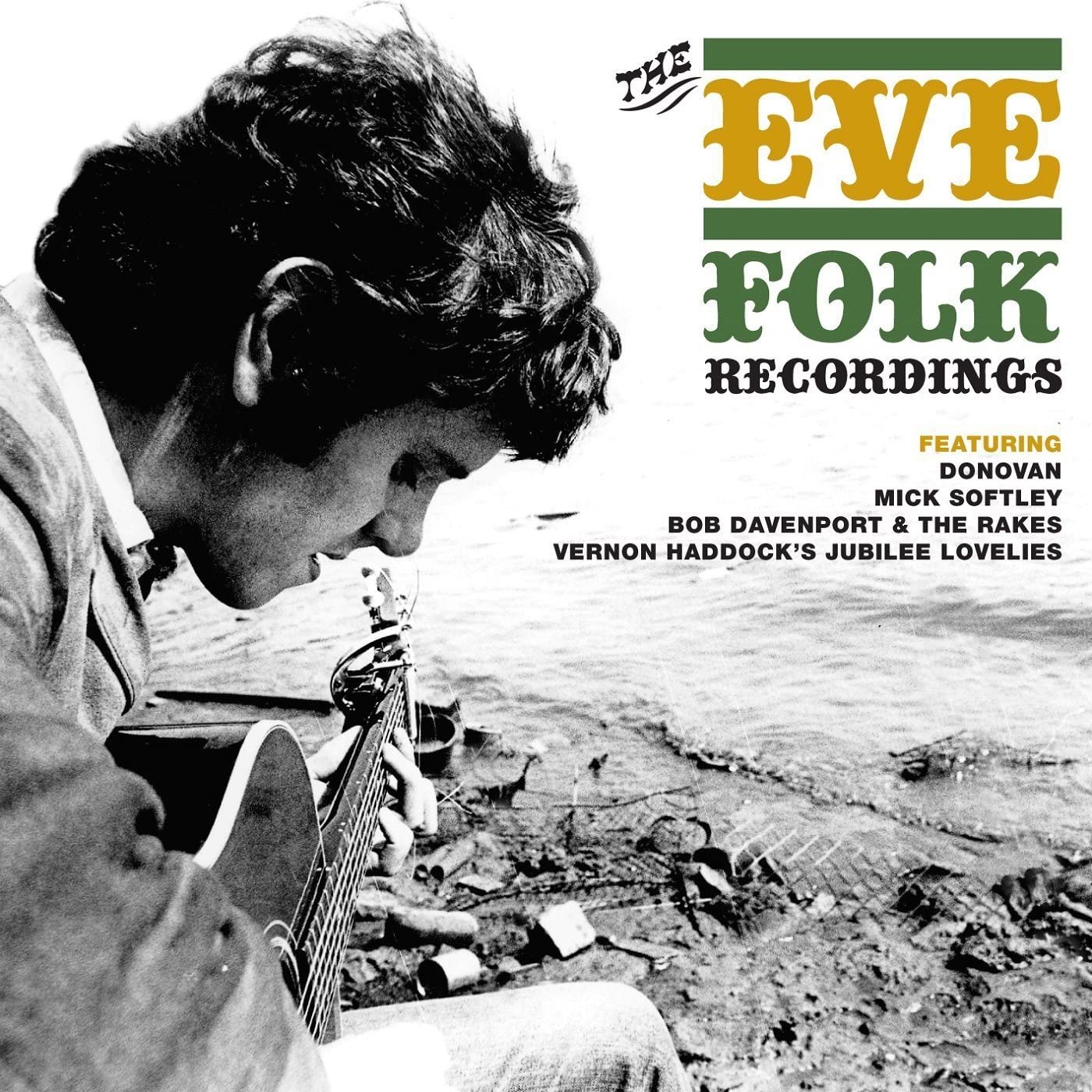

Mick Softley’s rare first album has been reissued as part of the double CD ‘Eve Folk Recordings’ (Retro D597) on the wide-lens RPM label via Cherry Red Records. Since 1991, RPM have steadily issued rare psych such as The Artwoods, Bo Street Runners, The Mindbenders, and The Five Day Week Straw People.

Eve Productions (Peter Eden and Geoff Stephens) first signed Donovan when supporting Cops And Robbers in Southend in 1964 but he left less than a year later (they won the court-case but only a derisory pay-off). Rumour has it that he recorded a 10-track demo tape, including ‘Catch The Wind’, but no mention of it here. They went on to produce or manage The Fingers, credited by some—rightly or wrongly—as Britain’s first psych band, GT Moore, Bill Fay (a parallel to Softley), Duffy Power, and The Crotched Doughnut Ring, but surprisingly missed the local Paramounts, later called Procol Harum. They also wrote hits for Manfred Mann, The Hollies, Herman’s Hermits and many more.

Mick Softley soon after adapted his distinctive brand of folk—a bohemian mix of protest, travel and love in one of the boldest voices of the era—into a rare brand of folk-psych cross-over, mostly solo live but with a band in the studio. This development has been surprisingly overlooked by some psych archivists since. From folk’s boom year of 1965, even his title ‘Songs For Swinging Survivors’—issued on EMI’s Columbia as part of a four-album deal with Eve—suggests the new coming scene. This reissue features the first-ever British anti-Vietnam protest song, ‘The War Drags On’, and Donovan covering his ‘Goldwatch Blues’ (about the exploitative workplace years before the Careers Opportunities and Zero-Hour so-called Contract), lifted without permission from his five-year older guitar tutor. It also features Donovan’s A-sides ‘Catch The Wind’ and ‘Colours’, the traditional folk-singer Bob Davenport with The Rakes, and the only LP by Vernon Haddock’s Jubilee Lovelies, a rare English jugband years before Mungo Jerry and McGuiness Flint popularised the style (Justin Hayward actually started the same way, before Moody Blues fame).

Softley lived the renegade-maverick life from the beginning. His mother came from Irish Catholic farming roots, his father from generations of East Anglian tinker ancestry but worked as a mechanical engineer. She qualified as a nurse and also assisted the famous Pankhurst family, the pioneers of the British Women’s Suffragette movement. (Young Michael started his first stamp collection thanks to them, even from the Emperor of Ethiopia, but swapped it precipitously for a tuck-shop drink.) Perhaps his life-long volatile sensitivity to injustice had its roots here. His first school was run by nuns but he preferred to ramble in his “playground”, the local Epping Forest, though he did take up the trombone. An avid swimmer, the lifeguards at the pool worked as club bouncers in the evening so he was able to get to see Ken Collier and skiffle. Jazz was superseded by blues, however, when he bought 78s by Big Bill Broonzy which completely changed his attitude to music. He bought a guitar on mail-order and taught himself to play.

Jesuit College in Tottenham didn’t result in the priesthood—he was more interested in girls he later recalled. Probably under his father’s guidance, he began an engineering apprenticeship but was sacked after a year due to absence. A brief stint in a factory ended when spraining his wrist while clocking in, so at 18, inspired by James Joyce and the Beatniks, he took his £50 savings and a friend to explore Northern Spain and France on a motorbike in 1959. It broke down in Barcelona, so they hitched to the mountains, and by Christmas were in Paris. Staying above the Mistral book shop in the Latin Quarter, he met Burroughs and Corso (soon tired of, he says) and “real people” among the buskers such as Alex Campbell, Clive Palmer (before founding the Incredible String Band), Wizz Jones and Ramblin’ Jack Elliott. A shifting British colony was earning a crust there that way, like Roy Harper, Ralph McTell, Davy Graham and Bert Jansch.

After three years on the Continent, he opened his own club at The Spinning Wheel in Hemel Hempstead, later featured in the ‘Pie In The Sky’ T.V. series. The raucous, tiny basement was open to the small hours, its barrel-raised stage hosting Donovan and a young Maddy Prior before Steeleye Span. There was quite a local scene: just up the road in St. Albans were two clubs, one preferring traditional folk and the other open to visiting American bluesmen like Dr. Ross (one of Softley’s favourites then was the one-man band Jesse ‘Lone Cat’ Fuller), as well as being within striking distance of the burgeoning London clubs. His friend of that time, Terry Cox, recently recalls Softley’s “rambling ways and roving eye…his biting political songs [and] anarchic attitude were the bench mark”.

But Softley was looking further afield than the folk “cult”, as he describes it on his debut’s uncompromising sleeve-notes (written by himself), with his cover shot on the bleak, smouldering Two Tree Island rubbish tip. It tells of the hirsute 24 year-old’s refusal to accept that individual responsibility should be subjugated to any organisation, political of course but also suggestive of the music scene generally. Forty years later he said that one of his songs was stolen and recorded by another who issued him with a contract as if he’d already agreed to them recording it. No royalties came from the first album, only from Donovan recording two of his songs for his albums and the charting Dave Berry’s B-side ‘Walk Walk, Talk Talk’.

Alongside three covers (Pete Seeger, Billie Holiday, Woody Guthrie) there are suggestions here of his later psych style. His distinctive rich-toned voice and guitar style alternating between percussive and intricate finger-picking mixes protest with travels and love: ‘Jeannie’ is a melancholy letter written by a drug-addict who’d left him. As Arash Torabi puts it on the Louderthanwar blog-site. “While the Beatles were hinting at drug use in their songs then denying it when questioned, Mick Softley was singing the hope that a lover would find a man not addicted to cocaine”.

A welcome bonus is the single released on Immediate a few weeks later, in November 1965: ‘I’m So Confused’ (a dig at organised religion, later reprised on his third CBS album in 1972) backed with the bluesy ‘She’s My Girl’. It’s his first material with a band, taking him further away from his origins into the electric music of the time. (It later appeared on the Virgin label’s ‘The Immediate Story’ in 1980.) The style was continued a year later with the Summer Suns for CBS: ‘Am I The Red One’ / ‘That’s Not My Kind Of Love’, the A-side a pure swirling psych classic. He must have had some clout as he produced it himself; certainly he had a higher profile in his recording days than later icons like Jackson C. Frank or Nick Drake. He was independent enough to record what he liked, he fondly remembers. He had a market-stall selling foam plastic, but a wine-making business was a disaster: one day he locked up the shop and never returned.

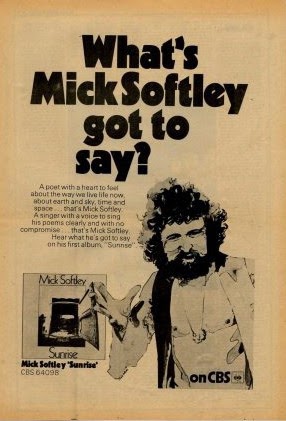

He briefly joined his friend Mac Macleod in the locally-based Soft Cloud, before the latter went to form the Danish psych heavyweights Hurdy Gurdy (he is the Hurdy Gurdy man on Donovan’s song). It also featured Jim Radford, later of Argent, on bass. While staying with his two children on Donovan’s Scottish island in 1969, Donovan encouraged him to record again, so there seems no animosity. Softley often played the flower-child’s ‘Poke At The Pope’ live, as well as uproarious pop hits of the time mischorded on purpose; his gigs were full of laughs and spilled beer. Derek Everett, who he knew from the Columbia recording, offered the singer a full-control contract for three CBS albums, this time with the well-known producer Tony Cox. Previously, he says, recording hadn’t been a positive experience: “a lot of hells and no heavens, a terrifying amount of personal pain,” but this proved different. CBS hoped he would be the English Bob Dylan to take Donovan’s title.

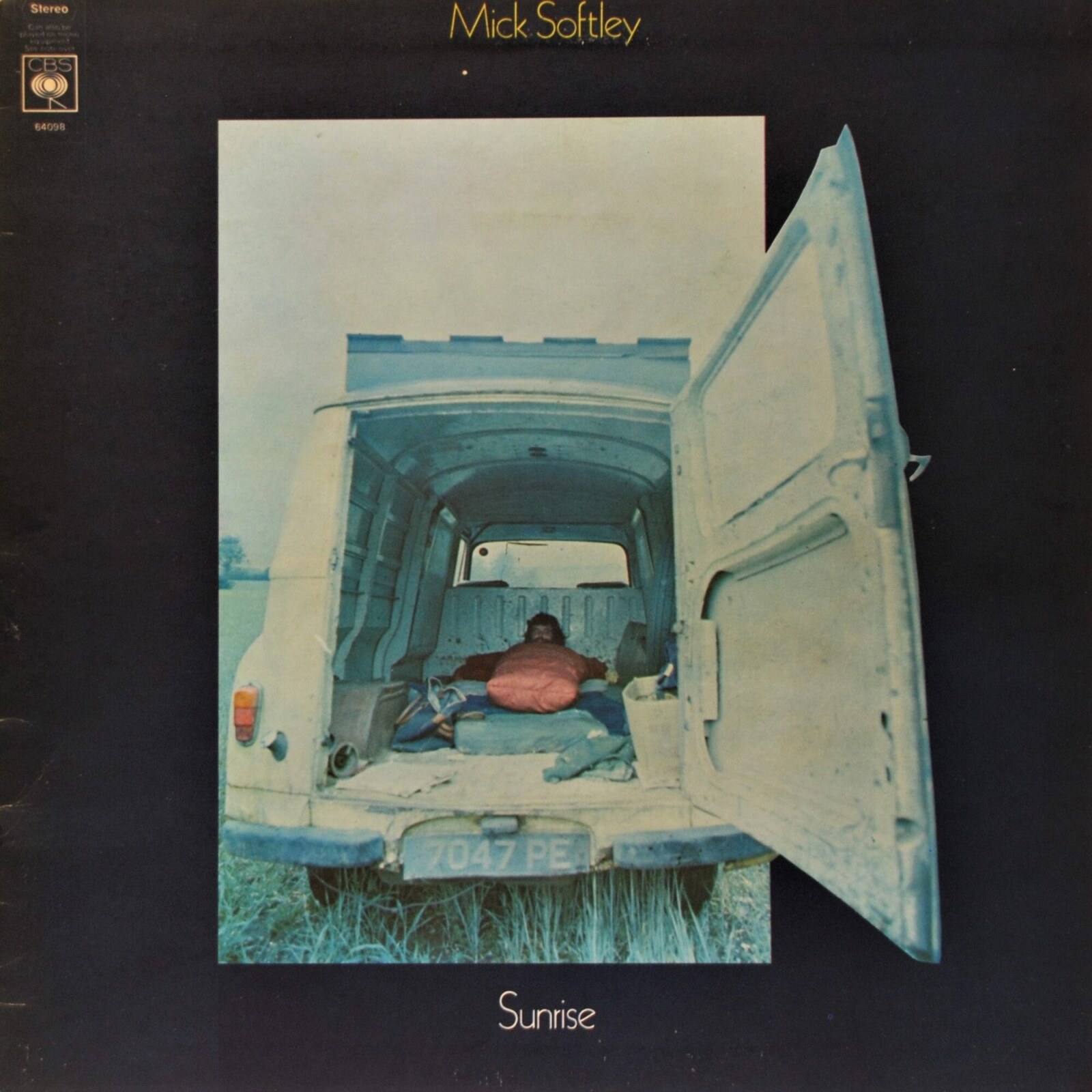

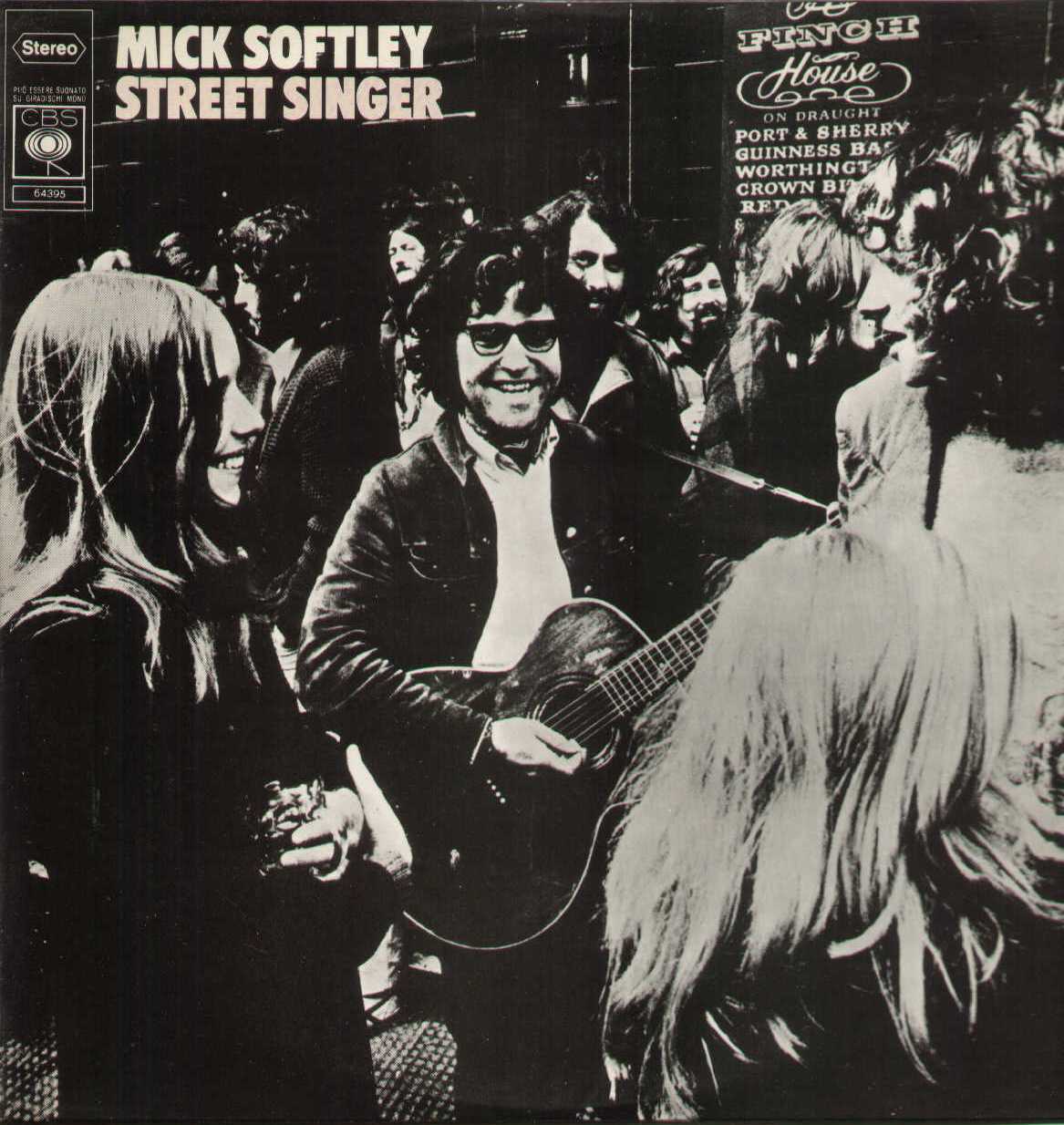

He was backed by a stellar cast of two dozen musicians including Richard Thompson, Lesley Duncan, Fotheringay, Trees, and Gringo among others, the producer also contributing piano and synthesizer. As adept at penning pop tunes as he was folk songs, the albums sit well with the period in a variety of styles from folk, rock, psych, Eastern with its sitars to jazz and even skiffle. He toured in a beaten-up van (his “fornicatorium” after gigs!) featured on the first CBS album’s cover; it must have been parked round the corner when I met him, somewhat bemused, in a tiny olde-worlde pub on Wimbledon Common around that time. He was like a human internet, spreading news about music, festivals, gypsy gatherings and much more. Music financed his lifestyle, that was its point, he told Record Mirror in an interview titled ‘Philosophy Of The Road’. His base was still near Hemel Hempstead, parking on a vacant plot in sleepy Flaunden or sharing a cottage in the winter with friends.

Sessions on ‘Sunrise’ (1970) were strictly professional. He told Zigzag, in its inaugural edition in April 1971, that he had nothing against drugs and alcohol but not during the recording: “I’ve been through all that stuff, and I know for certain that any form of art is a natural gift, it’s not something you can induce by drugs, alcohol or anything else—they won’t make you any more artistic”. Softley always saw music as a by-product of his reading and writing: “I like to think of myself as a craftsman, particularly when working with words—writing is one thing I hold in the highest respect”. Always adventurous, he is never introspective like Nick Drake, more a beguiling innocence like outsider literature with its barb in the tail.

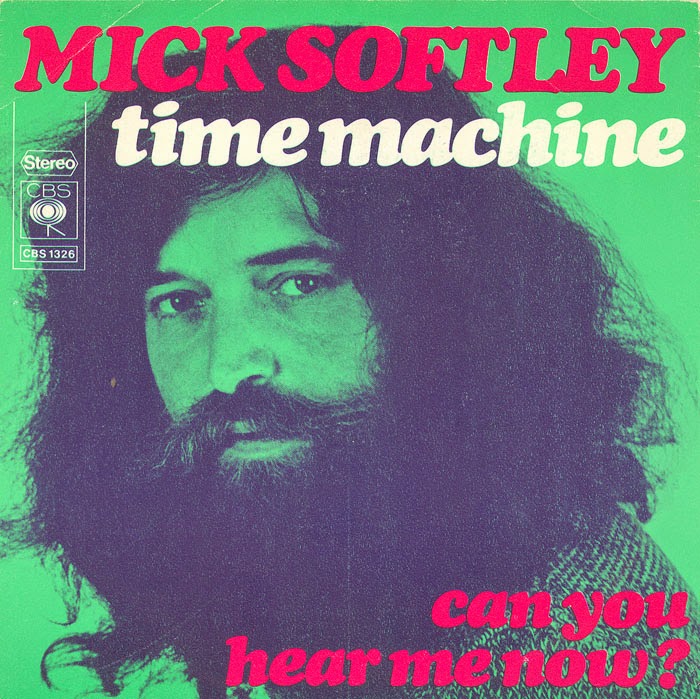

Period vignettes appear among the saxophones, sitars, strings and moog. The mellow ‘Eagle’ and ‘Waterfall’ (also on the CBS sampler Together in 1971), the rocking ‘You Go Your Way’ with a fine solo reminiscent of Gary Moore’s on Dr. Strangely Strange’s second album; a trippy ‘Caravan’; a varied instrument exploration amounting to a psychedelic-folk epic with surprising twists (‘Ship’), jazzy social-commentary (‘If You’re Not Part Of the Solution You Must Be Part Of The Problem’), closing with the over-eight-minute sitar-swirl of ‘Love Colours’. The most famous song is probably ‘Time Machine’ about reincarnation, a spacy 45 issued in picture sleeve in various countries and on the popular double CBS sampler Rock Buster (1970); it was apparently in the set-list of Soft Cloud too. Softley also featured on the French live compilation ‘C’est La Fête à Malataverne’ (1971).

In December he told ‘Melody Maker’ that his mostly new songs were to include blues on his next album, which is closer to him than folk. The interview is his usual blend of surprising frankness and modesty. “I do a lot of my writing after walking in the wood,” written quite quickly but takes at least a couple of months deciding if they’re any good. “I can’t think of anyone I like or admire in the world of pop. Maybe Richie Havens. The rest are incredibly sick, just singing about themselves in a life that just ain’t real. The pop business is a bloody great cardboard pyramid, and they live in it…It’s so banal it’s absurd!” It was the heyday of singer-songwriters like Cat Stevens, Jackson Browne and James Taylor, but in some ways the spotlight of their huge popularity overshadowed more demanding contemporaries like Roy Harper, John Martyn, and Kevin Coyne, who all contain some elements found in the equally original Softley.

The following year’s ‘Street Singer’ is more down to earth than its predecessor. Here his ‘Goldwatch Blues’ finds its natural home, a more moving rendition. A little more jazz and even ragtime too surfaces among the stories of ‘Going Down The Road’, ‘People Talkin’ ‘Bout Hard Times’, ‘I Seen Good Times, I Seen Bad’, and ‘Gypsy’ featuring the harmonica of Steve Hayton of Daddy Longlegs. ‘New Day, New Way’ is another long closer, an experimental mix of psych-folk and progressive with backing vocals by Doris Troy, an uplifting climax to the album.

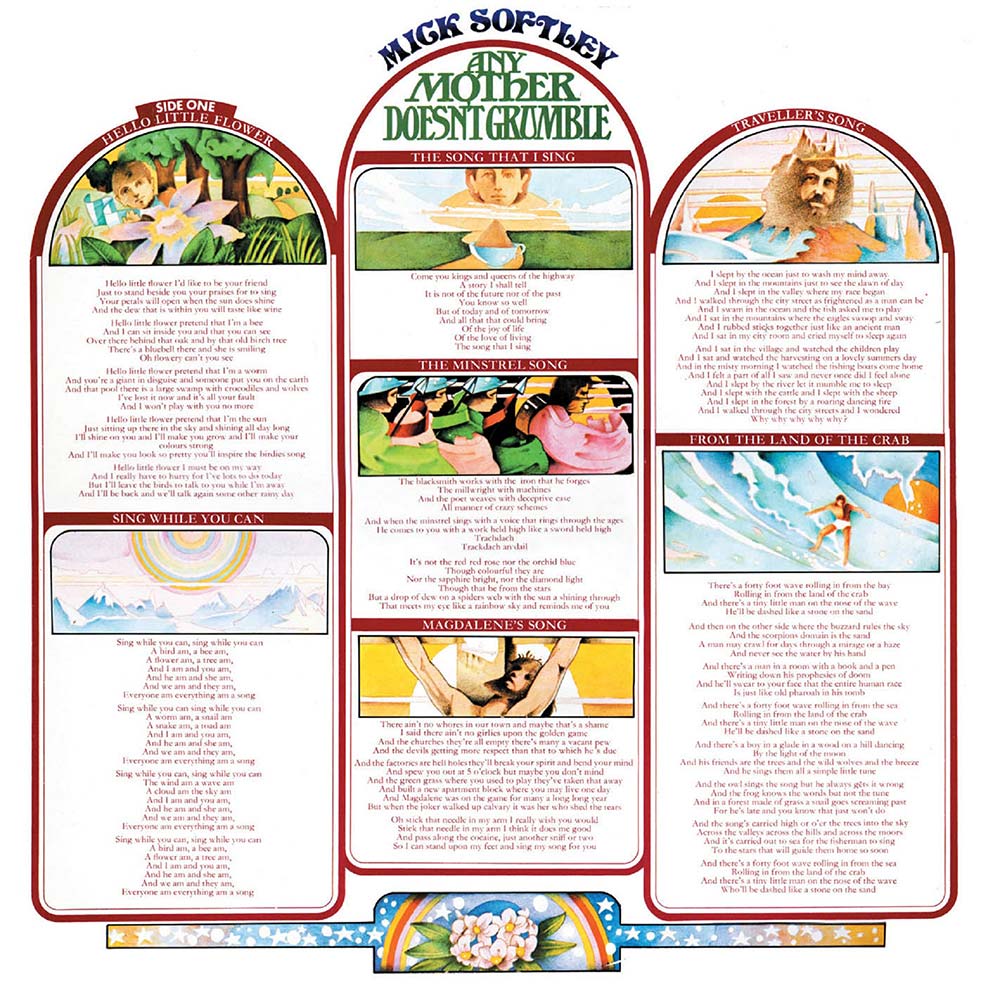

The final CBS album, ‘Any Mother Doesn’t Grumble’ (1972), was the most lavish with decorated lyrics and a beautiful illustrated inner-sleeve. It returns to the style and atmosphere of ‘Sunrise’, with elements of the Incredible String Band in their children’s lullaby mode (‘Hey Little Flower’; ‘If Wishes Were Horses’), bird-like flute on ‘Lady Willow’, worldly wisdom (‘Sing While You Can’; ‘Traveller’s Song’) and a reprise for his Immediate single ‘I’m So Confused’. But there is something else here, first hinted on ‘Sunrise’, which a few reviewers picked up on: “A majestic feel, creating images of some awe-inspiring vastness”, which is not going too far. ‘From The Land Of The Crab’ and ‘Great Wall Of Cathy’ would have been huge if done a few years earlier, an intense beauty that suggests we’re illicitly overhearing someone’s soul, also felt in ‘Have You Ever Really Seen The Stars’. He had one of the most strident but also melodic voices of the era, and his emotional storytelling of experiences and insights can carry a song to its own place that couldn’t be imagined to be by someone else. It achieves a rare high point here. The delivery isn’t always pure freakbeat—the styles always surprise—but the sentiments and ‘feel’ are of the same background.

This period saw him at the forefront: the CBS samplers but also Super Pop Session #3 in Germany; regular appearances at the famous Friars Club (headlining its first birthday bash over Wishbone Ash and Roger Ruskin Spear) and on Radio One’s ‘Sounds Of The Seventies’; the French T.V. show ‘Grande Affiche’; sharing top-bill at one of the first Roskilde Festivals in Denmark which still continues today; and an interview in the first-ever ‘ZigZag’ magazine. In ‘Disc’ (June 1972) it’s pointed out that he appeared a couple of times on the Steve Miller Band tour (and also Mott the Hoople), and he says he prefers that experience to folk gigs. He compares being the opening act to a road-sweeper, clearing the ground for the main act, “a similar kind of interesting job”! He likes the idea of an electric band backing his acoustic, but the format has to have structural harmony between the people to make it work musically. He returned for two vinyl LPs and then a cassette on Doll Records, a Swiss company where his French knowledge shows: ‘Capital’ (1976, recorded in Germany and mastered in Holland), ‘Mensa’ (1978), and ‘War Memorials’ (1985), often overlooked by fans and criminally never released on CD.

So Mick Softley’s last recording was a cassette, symbolically and in the spirit of the Phenix/Moore mockdoc on Youtube with its suitable schoolboy misspellings. Or even Peter Frame’s ‘Rock ‘n’ Roll Landmarks of the UK and Ireland’ (1999). Occasionally a letter surfaces, signed Michael F.P. Softley “the very same as Mick Softley”. He was living with travellers when the County Court made it illegal for them to travel public highways and told to leave. (How Britain still needs a Shelley, Cobbett or Tom Paine!) He moved to Northern Ireland just before ‘War Memorials’, perhaps partly because of his mother’s background (recently researching his genealogy he discovered that a grandfather had been a missionary in London’s East London, writing to the society for further details). He prefers not to live in England, where neighbours don’t speak to each other for 20 years but want to know your business. Occasionally he performed at the Belfast Folk Festival.

Twenty years later the equally-hirsute free-spirit told a local interviewer that he was indifferent to locals’ criticism, riding around Enniskillen on a bike because didn’t wish to pay tax for a car. He still didn’t like authority (the police for example “but not against law and order”), or what happened in Iraq (“a war about oil and money”). “I cannot tolerate fascists. America is fast becoming a fascist state with a small-minded fascist puppet in charge”. He wouldn’t be surprised if they did the September 11th atrocity themselves to gain world leverage. Softley became interested in science—he greatly admires Einstein—and spends most of his time gardening and writing on his four computers, publishing three volumes of poetry: ‘Etruscan Stone’; ‘Phonetic Values’; ‘Naked In Antarctica’. Then, sadly, three years ago he had a mild stroke while on his bicycle and now lives in a nursing home. Friends have set up a social media site for worldwide fans to keep in touch.

He always lived modestly and was self-effacing. When a journalist asked him at the height of his fame what he thought his IQ was, he replied “Not that much different from a tree”. Living the bohemian life of his songs and never wavering from an anarchic anti-establishment viewpoint, he epitomises the spirit of the 60s. Rob Young’s ‘Electric Eden’ in 2010 calls him “one of the most unjustly forgotten figures in the British 60s folk boom”, but neglected would be a better term as he remains a cult figure far and wide. He appears on that author’s soundtrack, but never saw himself as part of that somewhat insular world. Nigel Cross notes in the first re-release of Softley’s debut (Hux, 2003) that he was “far too original to be categorised and barcoded by the faceless suits that run the big record companies”.

The maverick is integral not only to that boom but also what it became in its various offshoots including psych, perhaps a contributing factor to why CBS’s hope of a British Dylan failed. ‘Record Collector’ (Jan. 2009) rates his single ‘Am I The Red One’ as #5 in their 100 greatest UK psych records, and regarding this reissue Kris Needs there believes that “Anything that gives recognition (and hopefully royalties) to the criminally overlooked Mick Softley has to be worthwhile”. It is surely long overdue to put his later output onto CD too, and a best-of compilation would compare well with anyone anywhere from the 60s. Mick Softley was always original, at no matter what personal cost, and his music displays the same originality deserving of wider appreciation.

Brian R. Banks

Many, great thanks for your very interesting article about Mick Softley.

The first time I met him, I was busking the streets of Haarlem (Holland) and singing his songs as well. All of a sudden a long-grey-haired, long bearded man stood in front of me, asking whose song I just sang. I recognized him from the cover of "Any mother doesn't grumble", so I answered: "It's yours!". He mentioned that apparently I was making good money. I asked if he doesn't busk anymore. He said he was working in a chips factory to pay for repair of his van.

"Do you do gigs sometimes?" "Not too many" he answered.

As I was doing gigs myself, organising everything myself, I proposed to look for gigs for him as well. He agreed. So I managed to organise several evenings where I played the supporting act and he did the second and main part of the concert. I loved (and still love) his music a lot at was very pleased to hear and see him doing his thing 'live'.

After some time a misunderstanding put an end to our 'collaboration' and I lost sight of him, never seen him ever since.

Shortly after that I found myself in Konstanz, Germany, still busking singing also his songs. There I met Clemens, a German guy who had lived in Freiburg in Breisgau a know Mick personally. He was delighted to hear sometimes playing songs, I found a few interesting gigs through him.

Now – many years later- I'm still a busker, mainly playing and singing in Switzerland during the fair season. From November until May I live in Bali, in a tiny village, there I film a lot and don't make a lot of music.

That's all for today. If interested, you are welcome to visit my youtbe.com/robvanwely 6 youtbe.com/robvanwelyAtBali channel

https://youtu.be/UDzGjqkkdr0 (Magdalene's Song).