Shattered Dreams & Broken Songs: An Interview with Ken Viola

Ken Viola’s ‘Shattered Dreams & Broken Songs’ emerges as an uncompromising record produced in a true DIY fashion.

His deep admiration for Neil Young forms a crucial part of his musical fabric. Viola recalls hearing ‘Flying on the Ground is Wrong’ from Buffalo Springfield as a transformative moment—a flash, a connection to the words, music, singer, group, and writer. In his own words, “I had the habit back then of playing the 2nd side of an LP first. Hearing ‘Flying on the Ground is Wrong’ from Buffalo Springfield, I felt a flash—a connection to the words, music, singer, group, writer, a feeling so all encompassing & total & beyond… if I close my eyes, I can go there right now! My over 50-year relationship with Neil Young—his songs, music, records, concerts, films, books, life—provides me with enlightenment, ecstasy, joy, trance, reflection, psychedelia, sorrow, pathos, repetition… Neil will never let me down; I named my first son because of him.”

Viola’s relationship with the Grateful Dead spans years. Though he was never a Deadhead, he began doing security at their concerts for cash and contacts, eventually forming a close bond with their road crew—most notably with Jerry Garcia, an amazing human being and conversationalist. As Viola explains, “When Garcia was on, the Grateful Dead could be great!”

“Everything I’ve written comes from real experience”

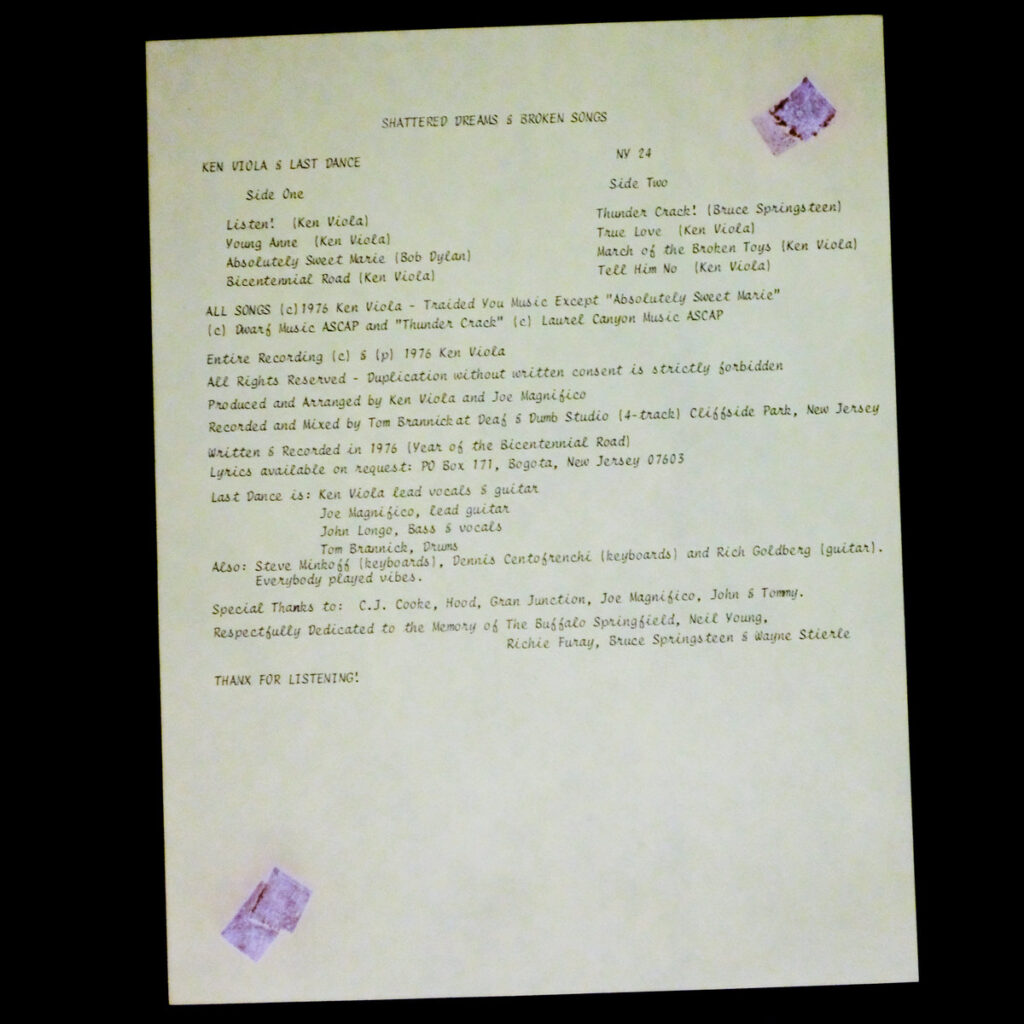

Let’s first take a look at your album made back in 1976, ‘Shattered Dreams & Broken Songs.’ What’s the story behind it?

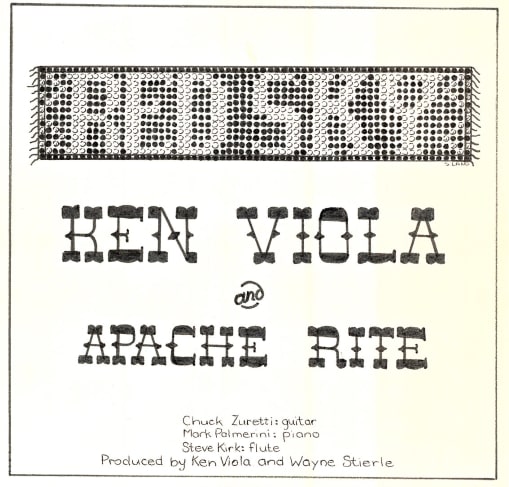

Ken Viola: In the late 1960s and very early 1970s, I was a singer-songwriter, accompanied myself on acoustic guitar, and played college gigs and a few notable clubs. I met people along the way who encouraged me, notably Wayne Stierle (Candlelight Records), Stan Nowak (who managed Jim Dawson with WNEW FM DJ Pete Fornatale), and most importantly, Tommy Brannick (Chips & Co on ABC Records, Swampseeds on Epic Records, Privilege on T-Neck Records, Manhattan Transfer with Gene Pistilli) and guitarist Joe Magnifico.

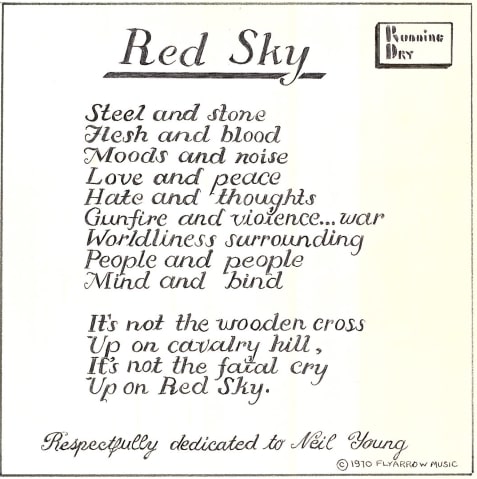

Tommy is a great drummer who has counted among his band members Dennis Ferrante, Jack Douglas, Joe Zagarino, Eddie Leonetti, and Gene Pistilli. He wanted to engineer and produce and began recording me early on. I had already been recorded at a major NYC studio by Wayne Stierle for a 45 record, ‘Red Sky’ b/w ‘Once Was Alone.’

My friend Chris Cooke brought me to see a band, Lewis Carroll, who was breaking up. I was instantly taken by the lead guitar player, Joe Magnifico (real name!). Turns out we were born in the same city and had met before, as our families knew each other. We started rehearsing in Joe’s basement with the keyboard player, Steve. I had a vision to blend my originals, cool unknown singer-songwriter covers, and vocals with unique instrumentation—all with pretty, atmospheric, jammy arrangements.

Just when we were ready to seek other instruments, Steve disappeared—turned out, he had gone to attend Berklee College in Boston. So Joe (who also played violin and pedal steel) and I formed a really good band named Gran Junction with a few other musicians. We never got out of the attic!

Eventually, Joe fell in with John Longo (guitar, then bass, vocals). We continued to record with Tommy throughout this time until we formed a new Gran Junction for what turned out to be a legendary show, opening for Ezra at the Playhouse on the Mall in Paramus, New Jersey. (More on this below.)

Not long after the gig, our rehearsal space was broken into, and most of our equipment was stolen. We were bummed beyond belief! There were months of inactivity, personnel and instrument changes… and when we finally reformed—new directions!

This lasted a while, gearing up to go out and play, but by then, the mid-’70s post-’60s economic depression had hit, and gigs were hard to come by.

So… I decided we would name the band Last Dance and bring it to the studio. Tommy graciously agreed to play drums, and we made ‘Shattered Dreams & Broken Songs.’

The album was made in a true DIY spirit. How many copies were originally pressed?

Wayne Stierle sent me to a pressing plant in West Orange, New Jersey, next to Thomas Edison’s Labs. I made 300, I think, but I lost 50 in Hurricane Sandy a few years ago. Some were sold in record stores, but most were sent to record companies, promoters, or given away.

Would you share your insight on the album’s tracks?

All of the tracks were recorded live, with very little overdubbing—that’s the way I’ve always worked. I probably redid the vocals live, as the room we recorded in was of average size. The arrangements were all about learning the song and going for it!

‘Listen!’

Ah, the games between men and women… teenagers… boys and girls… haven’t changed.

‘Young Anne’

My first love. Our story was tragic and full of twists and turns—too personal and painful to tell. When I went solo again, I performed a slower, longer acoustic version with an added middle:

“And the bartender, he mumbled, ‘Son, what’ll it be? You look down in the dumps, how ‘bout havin’ one on me? What’s your problem? Let me guess—you must be frettin’ over some kind of dream that just slipped through your hands.’

And I said, ‘How do you know what’s wrong with me?’ He smiled… ‘See all the people up and down this bar? They’re just like you and me. Some have been pushed too far—others, not pushed far enough—the rest, in between. It’s hard to cope when you realize life takes back what it means.’”

I played the new version for Anne, and she said, “This will make you a star.” I never wanted to be a star—I just wanted the girl!

‘Absolutely Sweet Marie’

Bob Dylan is still in my top five, and we did “Lo & Behold,” maybe a couple of others… but anytime I did somebody else’s song, I had to feel it all the way. This one fit with where I was at and the diverse musical styles I wanted for the LP.

‘Bicentennial Road’

The real ’60s started with the Kennedy assassination and ended with Nixon’s resignation—1964 to 1974. My father made me join the Young Republicans, although I was born left-handed. In the Republican headquarters above Womrath’s Bookstore in Hackensack, New Jersey, I was looking for something when I entered a large room. There was Richard Nixon—alone—talking to himself in multiple voices, personalities, and gestures! I walked out, quit, and never looked back.

A camp counselor saved my life—a great young human being. I saw him socially a few times after, but he was killed in Vietnam. I knew others who came home and were never the same. Given everything that had just happened in the ’60s and the divide in the country at the time, I was appalled by the Bicentennial celebration. Driving down River Road one day, I was struck by a golden vision of the water rising up to flood America. This song was my immediate reaction.

‘Thunder Crack!’

I had seen Bruce Springsteen play a few times when he was known as a lead guitar player down the shore. Joe Magnifico showed me his first LP, ‘Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J.’, and I loved the next one, too: The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. I started going to see them play a lot—they were amazing. Serious songs, his enhanced rhythm guitar playing, the ability to hold people in his hands!

I got to know them, really loved the early E Street Band(s), and decided to record ‘Thunder Crack!’—their set closer before he wrote ‘Rosalita.’ I added me some Elvis stutter. I gave Springsteen a copy of my LP outside the Stone Pony one night—never heard back—but Bruce, we did you proud.

‘True Love’

Oh, the hit single! The thing everybody is always trying to get. I never thought too much about it… but this song came to me while waiting on Joe. The piano player, Tommy, and I cut it—no bass, just two pianos and drums. At least the arrangement has integrity. We did new recordings of ‘True Love’ (writing the second verse 30 years later) and ‘Bicentennial Road’ on our 2010 LP ‘Feel.’

‘March of the Broken Toys’

When you reach for magic in a recording session, sometimes you make magic—but sometimes, it just happens. This was one of those times. And the jazzy vamp was spontaneous!

I believed in love at first sight, and although that’s only come twice for me, I was searching.

‘Tell Him No!’

For some reason, every woman I wanted was either involved, between relationships, or had just broken up! So, the theme of this record had become: here I am, with pure, true love just waiting for you! What’s the problem? (Ha!)

I had started with this ethereal nebulous called ‘Listen!’ but wanted to end the tug of love and war with ‘Tell Him No!’—at least an answer. I had known Gene Simmons of KISS when we were young comic book enthusiasts, and although I never listened to that kind of music, I was thinking of him!

We also almost finished an unreleased LP, ‘Revenge,’ recorded in 1976 and 1977, with horns, a couple of dual-guitar songs with movements, acoustic songs, and a pop tune… all written by me.

Side 1 (Harder):

‘Fable’

‘Revenge’

‘Jenny Broke the Mirror’

‘Wind Swept’

Side 2 (Softer):

‘All Alone Again’

‘1/4 Century Blues’

‘You Win You Lose Blues’

‘The Rose’

‘Love Story’

Alas, the craziness of the late ’70s (during which Bob Dylan said, “Wounds are still healing from the ’60s”) and other circumstances prevented the LP from being. Joe and I, with my son Dylan, did record “Wind Swept” and “Love Story” on our 2010 LP Feel.

What can you say about your songwriting?

I’m very proud of my songwriting. Everything I’ve written comes from real experience, channeling the essence of feeling. I started writing around the age of 15, and right from the start, there were some good things—this only increased.

Songs are funny. Like anything, you have to be prolific. Few write great songs. I was sort of holding myself to the best songwriters. At some point, I realized I may not be like them—may not devote my life to songwriting. But it turned out to be my vital release—an outlet for my emotions.

I wrote a number of great songs—organically, honestly, thoughtfully, personally. I reached the point where I could conjure a song out of the atmosphere, have it pass right through me, and emerge fully formed! And when I returned to songwriting after 30 years, on our 2012 LP ‘Incandescence,’ songs instantly flowed.

You mentioned playing in various bands. What about concerts?

We played a lot in private, unfortunately—not rehearsals, but song after song, all the way through, nearly all originals.

There was one famous show at the Playhouse on the Mall (which did plays and underground art movies) in Paramus, N.J., in 1973. Michael Levine, a local entrepreneur who later became one of the best publicists in LA, was promoting a popular local band, Ezra, featuring Joe Lynn Turner (Fandango, Blackmore’s Rainbow, Deep Purple, Solo), a friend who grew up in the same section of Hackensack as me.

I was working at the legendary Capitol Theatre in Passaic, N.J. During a break, Joe Magnifico and I were sitting on the lobby heater when Michael approached us and asked if we wanted to open for Ezra. We looked at each other and said yes! We put the band together in just a few days!

We opened with a thunderous, jamming version of David Blue’s “Outlaw Man.” I had asked the lights to stay black. When they were switched on, I had a double-barreled shotgun pointed right at the audience! Played a couple of originals and songs by Gene Pistilli, Neil Young, and Paul Cotton… at the end, we were given a standing ovation!

I also made a couple of guest appearances with Joe and John’s later band, each time performing unreleased songs from ‘Revenge.’

Now let’s go way back. Where were you born, and what would you say were some of your early influences?

‘I was born in January in the middle of a snowstorm. My father was fighting in Korea, and there was no one to keep my mother warm.’

My early influences were beautiful ballads, Peter Pan, Elvis Presley, reading comic books, and magic. At 13 or 14 (1965-1966), the radio became a big influence—Nina Simone, Bob Dylan, The Pretty Things, The Yardbirds, The Byrds, Love, 13th Floor Elevators, The Blues Project, Small Faces, Buffalo Springfield, and many others. Teen Set magazine was also an influence. By 15 (1967), I was into psychedelic, blues, soul, jazz, country, folk, Eastern music—a melting pot of sounds.

What was the music scene like where you grew up?

The scene where I grew up was interesting. Hackensack, as the Bergen County seat, had a long main street shopping area that attracted people from surrounding towns, and several high schools fed into one. It was a small city with a mix of ethnic and economic backgrounds—a merging clash of cultures. A gateway to the suburbs of North Jersey. (When people think of New Jersey, they usually picture Newark and the Turnpike, not Northern New Jersey or the Jersey Shore.)

Did the local scene have any impact on you, either as a musician or as a music fan?

A huge impact. There were several influential record stores—Karl Olsen, the Singer sewing store next to the library (which still had a listening booth at the time), and the most famous, Relic Rack, where I worked for records with my lifelong friend Hood (who now works with Southside Johnny). Department stores were starting to carry records, too, and there were even a couple of recording studios on Main Street.

Relic Rack was owned by Eddie Gries and Donn Fileti, who loved vocal groups (doo-wop), hence the store’s name. They even had a record label and put out some successful a cappella 45s and LPs. They hired Wayne Stierle as manager—he adored Elvis—and let Hood and me hang around to advise him on the emerging new music scene. We also had to spin soul records for some customers who could only afford a few purchases. Many musicians came in—Tim Bogert, Pete Sando, and others.

The first local bands I remember were The Iridescents (with members from several towns), The Filet of Soul (ethnically mixed), Sun, and The Other Side. My first cousin, guitarist Chuck Zurretti, played in Aphrodisiac. Great guitarist Jim Anderson was in Muffin (in a 60s paradox, he later taught my musician son Dylan at Northeastern decades later). There were many bands.

Dances were held at the Y, in church halls, gyms, auditoriums, and teen clubs. Bands played songs they heard on WMCA AM radio, and later, the dawn of FM radio—rock, soul, Motown, British Invasion, underground music, and records both domestic and imported.

One of the coolest happenings was the Battle of the Bands. Several groups would set up in different corners, play short sets, and the crowd would vote. The winner would do an encore—usually playing the same songs again. Bands often broke up and poached players from each other, leading to creative new configurations.

“In all the decades since, nothing has come close to the wonder-filled Fillmore East. The best place ever!”

You attended a lot of concerts, especially during the “golden age” of Fillmore East. What are some of the most memorable artists you saw there? We would love to hear stories from your experiences at Fillmore East in its full glory.

The first moment I walked into the Fillmore East, I thought, “My parents are wrong; there is a place for me.” You entered through a narrow tunnel with a ticket office (only part of it remains today), then emerged into a dreamlike gold and green mirrored lobby. Through the looking glass, indeed. Straight ahead were half-walls with glass on top and open-air above. From here, you could enter several aisles to the velvet orchestra seats or float up the sweeping staircase on the left to the Bummer Palace (a dark space to escape the stimulation if you needed to), refreshments, mezzanine seats (only a few rows hung over the back of the orchestra), and the balcony seats (sloped up over the lobby and vestibule). Every seat was great!

Bill Graham and Kip Cohen had offices in the basement. Backstage consisted of small rooms in the stage-left corner, accessed by climbing a metal spiral staircase. The staff were all firm and friendly, easily identifiable by their green shirts with gold lettering.

The incredible sound was mixed by John Chester from the house-right private box, close to the stage (not 90 or so feet back center, which became the norm). My friend Chris and I went to watch the demolition when the venue closed, and the architecture—curves and depth, no hard surfaces for the sound to bounce—was amazing!

The light shows were incredible, hand-operated from the elevated upstage horizontal platform behind the full proscenium screen. They projected on the groups and on the screen, seemingly in sync with the music—swirling, deep-moving colors, shapes, formless.

When The Band (on their ‘Music from Big Pink’ tour) played, the screen showed a journey through the backroads of the Catskill Mountains on a beautiful day. When Traffic played, they lowered a real traffic light. When Jefferson Airplane (with a pregnant Grace Slick) performed ‘Volunteers,’ they lowered a huge American flag.

Procol Harum (an underrated live band), The Collectors (fantastic ‘What Love Suite’), The Hello People (‘Anthem,’ mime), The Band (on the ‘Music from Big Pink’ tour), Jefferson Airplane (several times—when they were on, they were hypnotic!), Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young (many times—no light show!), Spirit (fantastic live), The Who (did ‘Tommy’ and more), Humble Pie (many times, one of my favorite live bands), King Crimson (original lineup, 11/21–22/69), Fleetwood Mac (with the incredible Peter Green and Danny Kirwin jamming madness), Joe Cocker & the Grease Band (many times, great vocalist, underrated live), The Nice, Neil Young & Crazy Horse, Quicksilver Messenger Service with Nicky Hopkins, Pink Floyd (twice, both great—’Atom Heart Mother’ with orchestra and choir), Grateful Dead (‘Dark Star,’ Mirror Ball/Naked Girl dancing just for me), Traffic, Fairport Convention with Richard Thompson, Cat Stevens, Leon Russell, Elton John (believe it or not, fantastic performance), Poco (underrated live), Manhattan Transfer with Gene Pistilli & Tommy Brannick—these were just a few of the highlights.

In all the decades since, nothing has come close to the wonder-filled Fillmore East. The best place ever!

“As far as I know, I am the only one to have released a Neil Young song that he hasn’t.”

Let’s break the following questions into two parts: one about Neil Young and the other about The Grateful Dead. You wrote the Box Set essay for Buffalo Springfield and recorded High School Graduation by Neil Young, backed by members of the E Street Band. You also worked with The Grateful Dead for decades.

Buffalo Springfield is my favorite band, and Neil Young is my favorite artist. I have a broad palate of music, mostly from the 20th century, spanning the 50s through today, with some things from before and after. The best period for me remains 1965–74; I see little progression since. However, the pervasive influence has lasted longer than any other popular music (though classical pieces have lasted in and of themselves).

The reason for this is the merging and melting of musical forms into sounds that were heard as new. The emergence of guitar as the lead instrument blended (or “bleshing,” as Sturgeon would say), and the outpouring of youth culture, freedom, rebellion, politics, drugs, all fed into a group consciousness. (As put forth by Sturgeon in More Than Human [1953], a book many great 60s musicians read).

Back then, I had the habit of playing the second side of an LP first. When I heard ‘Flying on the Ground is Wrong’ from Buffalo Springfield, I felt a flash—a connection to the words, music, singer, group, writer. It was a feeling so all-encompassing, total, and beyond. If I close my eyes, I can go there right now.

Being asked to write my essay, Incandescence—Memories of Buffalo Springfield, for archivist/photographer/musician Joel Bernstein, and having all five original members approve the inclusion in their box set, was a high point in my life.

My over 50-year relationship with Neil Young—his songs, music, records, concerts, films, books, life—has provided me with enlightenment, ecstasy, joy, trance, reflection, psychedelia, sorrow, pathos, repetition… Neil will never let me down. I even named my first son after him.

After I was unable to finish my second LP, I hit the wall at the “end” of the 60s movement. I was post-Beat, pre-Hippie. The worldwide contents of the relatively small underground seemed to consist of rich kids (mostly from divorces), a certain breed of middle-class rebels, and weirdo crazies from various ethnic groups who accepted each other. Music was the soundtrack, war, civil rights, and drugs were the fuel, and youth provided the energy. All of this changed gradually when the mainstream and middle class were exposed to the music, concerts, and drugs. The drinking age was lowered to 18 in America, and the war ended (though, has it?).

Some hit the wall during, and for me, it was after.

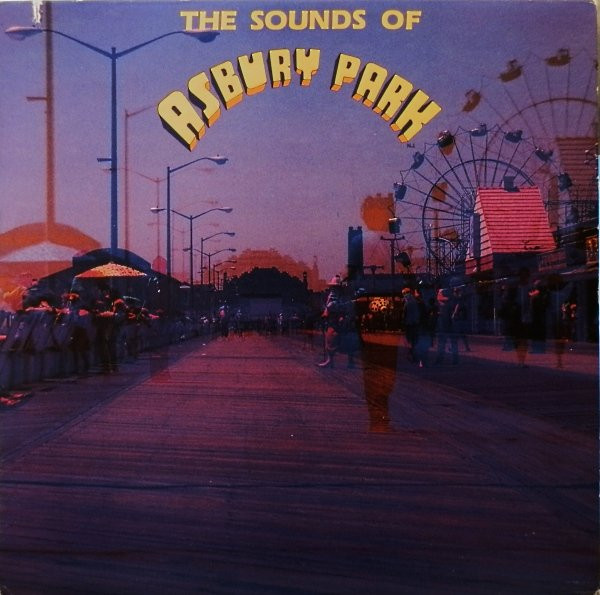

As I was closing the door (or so I thought), Southside Johnny introduced me to his managers, who hired me. While on the road with Johnny, I thought of recording some of the better bands playing down in Asbury Park. This was attempted, but we couldn’t capture the excitement. So, I decided to produce an anthology studio record, which became ‘The Sounds of Asbury Park.’ All of Southside’s band (except Billy Rush, who was busy writing), including Johnny, played. Lord Gunner (Lance Larson & Rick Desarno) turned out to be the only actual band on the LP, with Tico Torres (Bon Jovi) as their drummer. Kog Nito & the Geeks were a studio band with Ben Newberry & Pete Croken, who worked with Southside. Lisa Lowell, a singer along with Patti Scialfa (married to Bruce Springsteen) & Soozie Tyrell (in Springsteen’s bands), sang lead on one of their songs. Paul Whistler was backed by the Jukes & the Ladies (who then joined the group). Sonny Kenn was joined by Garry Tallent, David Sancious, Vini Lopez, Ernst Carter, and Southside.

Kevin Kavanaugh, the great Asbury Park keyboard player, was a big part of the LP. He knew of my record and suggested I include myself as an artist. I wrote the song ‘Janey,’ for my true love, my wife Carol, and recorded it with Vini “Mad Dog” Lopez on drums and vocals.

I found out from a collector about a song by Neil Young I had never heard of—High School Graduation (which turned out to be a song from his unrecorded first solo album post-Buffalo Springfield, about the complexities of feelings and experiences in high school). I obtained the lead sheet from the publisher, and Kevin and I arranged the track. We recorded it with Garry Tallent and Vini Lopez. It featured a brilliant duel lead feedback Springfield homage by guitarist Joel Gramolini, and a climactic sax solo. With help from the great concert promoter John Scher (I worked for him for many years, both part-time and full-time) and through Elliot Roberts (I had met him and Neil many times over the years), Neil approved our recording. As far as I know, I am the only one to have released a Neil Young song that he hasn’t.

The LP was released in 1980 on Thunder Road/Visa Records and received some great reviews, except for a mean spot of revenge by Dave Marsh in Rolling Stone. We did a well-attended live concert at the end of the summer at the Paramount in Ap. We tried to get a tour together to promote the LP and played a couple of dates before the end.

I’m really proud of my production of ‘The Sounds of Asbury Park.’ Great record. However, I would not sing, write, play, or record for 30 years.

The Grateful Dead

I was never much of a Leary fan, but you can count me in regarding Ken Kesey and Neal Cassidy. The architects of the real first ’60s movement were thinkers, seekers, travelers, doers—not layabouts or stoners reveling in their grooviness. Jerry Garcia is one of the pillars.

I was never a Deadhead, but friends were early fans. They played the first album for me. I liked a couple of the songs, but not the sound. (Later, they would reissue a better version). The second LP had sound issues, too, but that’s it for the other one; the Cassidy biopic is sublime. ‘Aoxomoxoa,’ adventurous songs & arrangements. “You’ve got to see/hear them live,” so I did and loved ‘Dark Star,’ but I had missed the fierce performances, like on the fantastic ‘Live/Dead’ and ‘Two from the Vault.’ ‘Workingman’s Dead’ is their end-of-the-‘60s commentary.

Beginning with ‘American Beauty,’ they started to become big.

Most great ‘60s bands played for great heights, but to reach those heights meant inconsistency, also due to poor conditions like weather, travel, bad sound, less-than-ideal buildings, promoters, etc. When they would attain the group mind and fire on all cylinders, something greater was achieved! So much so that many bands could not get that sound on record. The Dead’s live consistency (an ongoing musical conversation with each other) would carry them to the top of the concert business (and influence other imitators) for decades.

Their audiences, after gaining popularity, dubbed Deadheads, were challenging to say the least, due to imitation hippies, irresponsible drug and alcohol use, violent behavior, overdoses, throwing themselves at the straight communities, and battles with authorities.

I began doing “security” at concerts for cash and to make contacts for my music. I felt strongly about helping ensure that live music and the ‘scene’ could continue, come what may. “Be careful what you wish for,” huh? So I started to do a lot of Grateful Dead shows, became “friendly” with the Dead’s road crew (which meant being really great at your job), and, in particular, with Jerry Garcia, an amazing human being and conversationalist, who could get right to the essence of the discussion in a succinct way. We would talk about comic books (E.C.), science fiction (Kurt Vonnegut, Philip K. Dick), movies (Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein), drugs (he loved to get high, although LSD was great for the first time, but after a while, it was fighting off the creepy crawlies), music, and anything or everything. Jerry was always in search of new pure bliss, akin to being able to push your endorphins! And man, could he play! When Garcia was on, the Grateful Dead could be great!

They stopped doing live shows around the mid-seventies, but when they returned, everything for them was enhanced. John Scher started doing all of their shows from the Rockies East, and they asked me and Hood to drive around the northeast and help.

A few years later, I would be needed to go on the road with them to allow access to their stage. They continued to get bigger and bigger, as the audience grew to include camping, selling things outside the venues, and three generations of Deadheads: older, college-age, and younger—all sorts of problems.

With the event of ‘Touch of Grey’ and ‘In The Dark,’ everything multiplied, and I became their “head of security,” right to the end (and beyond, with Furthur). I dealt with communities, politicians, promoters, venues, Deadheads, road crew, and the band, all while doing the best I could to try to keep the concerts going. The Grateful Dead arranged their concerts in two sets to assimilate the rise and fall of a trip. Every day with the Dead was like tripping!

What currently occupies your life?

After rising from the dead, I spent more time with my family and continued to provide security at concerts in New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania. In 2009, my son Dylan found a box of tapes in the basement and was surprised to discover me! At the same time, Joe Magnifico and I reconnected, and the four of us (including my son Neil on some cuts) recorded ‘Feel.’ The LP was composed of new versions of two songs from ‘Shattered Dreams & Broken Songs,’ two from ‘Revenge,’ and covers by Love, the Yardbirds, the Byrds, Townes Van Zandt, the Everly Brothers, Rick Nelson— all favorites of mine! In many ways, Feel picked up right where we had left off in the late ‘70s.

In 2011, I was asked to put together a special 30th anniversary concert celebrating the release of ‘The Sounds of Asbury Park’ album on April 1 at the legendary Wonder Bar on Ocean Avenue in AP (once the longest bar in the world!). Boccigalupe & the Bad Boys, Lance Larson (Lord Gunner), and Sonny Kenn played sets. I did my two songs from the LP and one from ‘Cosmocopia,’ backed up by my son Dylan and Asbury legends Steve Schraeger (Cahoots), Sonny Kenn (Sonny & the Starfires), and Bobby Bandiera (Southside Johnny, Bon Jovi, solo). It was my first time onstage in 30 years. A fantastic night!

I set my sights on writing a concept record, capturing my thoughts, feelings, and life—from my memories in the womb to imagining what will happen to my consciousness when my body ceases to live. I had just turned 60 years young and wanted the music to reflect: orchestral, blues, country, rock, power pop, jazz, symphony, folk, psychedelic, and free form. Joe Magnifico, Dylan Viola, and I wrote, performed, and produced this in just 15 days, as time allowed. We released Cosmocopia in 2012.

I selected the following quote from the master film director Tarkovsky to illustrate: “Longing for our inner home; inner sense of belonging; a pining for what is far from us; for worlds that cannot be united. The meaning of life; the meaning of freedom & insanity. We suffer from internal fragmentation: that of not being able to unite the entire world within oneself; all that is good; people, emotions & spirit.”

On January 1st, 2018, upon reaching the magic age of 66, I left the workforce to continue pursuing knowledge, music, living, and beyond!

If you are interested in ‘Shattered Dreams & Broken Songs,’ my songs from ‘The Sounds of Asbury Park,’ ‘Feel,’ or ‘Cosmocopia,’ go to: https://vmmusic.bandcamp.com

The link is for music streaming, pay-what-you-like download (including free), and to read lyrics (click on the song, then to the right).

Would you like to share any final thoughts with the readers of It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine?

Thank you, Klemen! It’s Psychedelic Baby is cool, informative, and so vital in this 21st century we find ourselves in—disconnected yet connected together. We seek nature, tribes, true human interaction, the rediscovery of magic, visions from dreaming, and understanding. Music is the universal language of the gods, harmonic highest consciousness, or unconscious existence. Hope, peace, and love!

Klemen Breznikar

Ken Viola Bandcamp