The Underground Jazz Scene in Hungary

The underground jazz scene in Hungary, as documented by the Turkish psychedelic rock musician Işık Sarıhan.

Hungarian underground jazz is a thing, and it deserves wider recognition. It’s a contemporary music scene that’s happening today and evolving as we speak. It’s creative and impassioned, and it’s open to many other genres; yet alongside the diversity it exhibits, it also has an internal coherence, cemented together by the overlapping vision of its members and their musicianship that extend throughout countless combinations of individual performers, and by various historical, local conditions and currents that shaped its broad outlines. Even though its borders are fuzzy and flexible, it qualifies as a distinctive musical phenomenon from the perspective of music history and socio-musicology, and for all practical purposes it needs to be conceptualized, recognized and talked about as such. This is what I aimed to demonstrate with the compilation ‘The Underground Jazz Scene in Budapest Today: an Adventurous Introduction’.

Even though the compilation has the ambition of serving as an objective document, it should be mentioned that the factor of subjective personal taste did unavoidably play some role in the choice of tracks: it’s a collection put together by an experimental rock musician with a Turkish background and a fascination with global traditional sounds, and it’s no coincidence that the tracks often tend towards the heavy side, frequently feature non-Western elements, and often carry the overtones of that hard-to-define otherworldly mood which is often called “psychedelic”. Indeed, the only reason I have not titled this album as a collection of “psychedelic jazz” is that I did not want to repeat the mistake (often made by Western commentators in the context of the history of Turkish folk pop or folk rock) of overusing a term that is ambiguous between ascribing a particular mood to a piece of music and making a reference to that music’s historical connections to a specific musical style or subculture. Not all jazz that is psychedelic is necessarily psychedelic jazz, so to speak. And when it comes to the “jazz” element in the title, it should be noted that it denotes more of a common ground, shared background, historical framework, or beginning point from which the presented music had initially sprung; in some cases to eventually arrive at places where we find not much of the chords, moods, rhythms, song structures or instrumentation that is typically associated with jazz: the unclassifiable experiments of Dorota that resemble so-called “freak folk” more than anything else, the punky jazz of the Kinetic Erotic trio with a setup that seems to be modeled on Hungarian wedding bands, Sauropoda’s complex oriental pieces that move a bit more towards heavy math-rock with each release, or the surrealistic microtonal sceneries of Decolonize Your Mind Society are a few examples.

“I saw a taxi driver listening to jazz, and it was my first musical impression of Budapest”

I stepped into Hungary for the first time in 2009 as a 24-year-old graduate student on my way to my first conference abroad. In the airport, the generous professor who I travelled with on the plane from Turkey invited me to take a taxi with him on our way to the city. It was the first time (and perhaps the last time too) that I saw a taxi driver listening to jazz, and it was my first musical impression of Budapest. As I walked the colorful, atmospheric streets of the town in the following days, I thought this was a city the character of which would go perfectly with jazz, while melodies from Frank Zappa’s ‘Hot Rats’ kept popping up in my head. I thought my interest in jazz would grow if I were to ever live in this city, a genre which I had a complicated relationship with.

I indeed moved to Hungary a year later to continue my studies, but my musical life didn’t immediately move towards the direction I had imagined during my first visit. My established habits made me search for scenes and niches that I was familiar with from Turkey, where the most interesting and innovative musical acts were born not out of the experimental jazz scene (that barely existed) but the experimental rock scene, which had one foot in the folk-inspired Anatolian rock movement of the 60s-70s and another foot in contemporary alternative styles of music. My own band Hayvanlar Alemi, a psychedelic folk rock unit, was also a product of this scene, though we differed from many of the scene’s typical acts as we actively looked for sources of inspiration not only in Turkish and Western musical history but also in the rest of the world, especially in the hybrids of traditional and innovative styles; a story we told in detail in an interview with this magazine around nine years ago.

Upon settling down in Hungary in 2010, I immediately started looking for whatever could be a local counterpart of musical movements of the 60s and 70s around the world like Anatolian rock, Cambodian rock, Afrobeat, or Peruvian psychedelic cumbia, and contemporary experimental bands that were connected to and built on whatever that tradition would be; but it turned out that not much music in this vein could be found besides scant examples. In general, there didn’t seem to be a very vibrant experimental rock scene. I was lucky enough to have a professor who, after a conference dinner just a few weeks following my arrival, took me and two other curious PhD students to the edge of the city for a concert of two legendary bands from the 80s, Korai Öröm and VHK, the latter which had recently reunited. Even though these bands’ brand of shamanistic rock and punk was a genuinely local phenomenon (and I was going to discover later that they had interesting contemporaries like the avant-garde folk-rock-jazz unit Kampec Dolores and the lo-fi synth folk wizard László Waszlavik), I had a hard time finding their predecessors or successors in the country’s musical timeline. In the following years I was going to realize better how the political history of a country can play an interesting role in whether local traditional music would be embraced or shunned by that country’s creative class, an issue I return to in the interviews with Hungarian musicians below.

One moral of the early phase of this exploration was that, leaving aside a few exceptions, it was not so much during the 70s but the 80s that the more interesting things happened in the Hungarian music scene. However, even though there were many other intriguing musical acts from or rooted in the alternative rock and post-punk circles of the 80s, a full appreciation of these required understanding the language, which I didn’t. By the time I founded my online label Inverted Spectrum Records in 2015 and started to put together regional compilations soon after, I still hadn’t found my proper musical niche in Budapest despite many attempts at delving into various historical currents and contemporary subcultures.

It took me no less than ten years to arrive at the full recognition that in Hungary one has to turn to jazz to find the kind of elements I was looking for in music. Here, it was more common among musicians with a jazz background to look into idiosyncratic, authentic and colorful ways of expression, and to adopt the kind of open-minded attitude which leads to the creation of a scene that can accommodate the elements of contemporary experimental music, punk, avant-garde rock, electronics, and folk; even though many of these musicians had formal conservatory training which, in some circles, is normally associated with a narrower mindset. It is possible to speculate that a historical reason for how jazz in Hungary has differed from rock in this respect might have something to do with the fact that jazz is a relatively more abstract instrument of expression and therefore has probably established itself as a more fertile ground for artistic freedom in a country where, during the era of the single-party state, rock ’n’ roll and other innovative music rooted in it has faced more bureaucratic obstacles due to its more salient rebellious character. As some of the musicians discuss in the interviews below, obstacles and limitations can sometimes lead to interesting musical directions, even today.

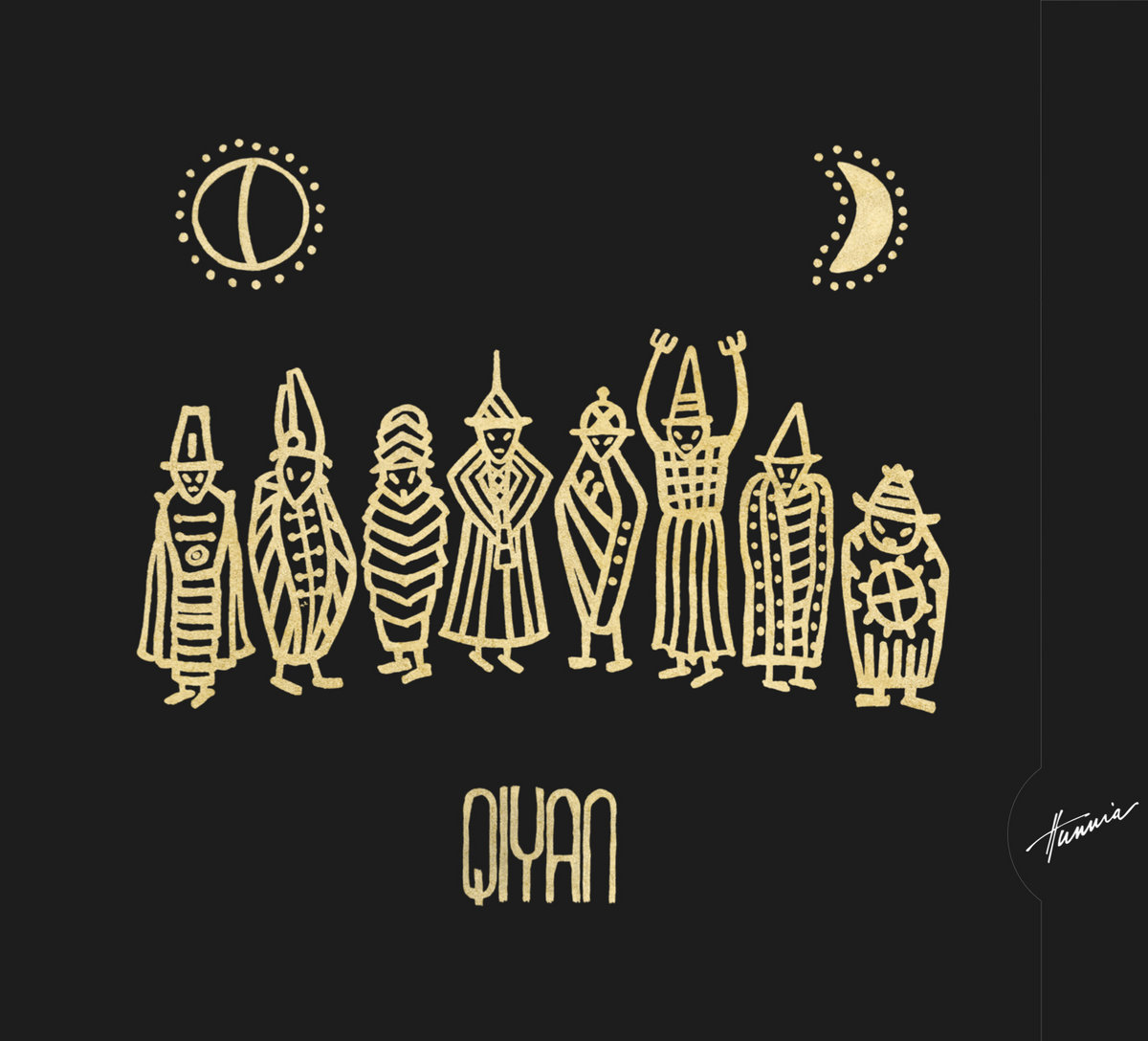

Hungarian alternative jazz is not a very big scene in terms of the number of musicians: one could easily make a list of twenty-five musicians or so in the center of the musical activity without whom the scene wouldn’t be what it is; however, almost all of the performers play in multiple bands and improvisational formations, adding to the scene’s prolificacy and diversity. Reading the credits in the compilation one might notice that several names are repeated, such as the drummer Áron Porteleki who shoulders the drum kit in all of the last five tracks in the album, which is only a fraction of the projects he has been involved with, in various roles and with various instruments. However, even though the performers are tightly knit together, within the numerous connected nodes one can still observe clusters of tighter connection. There are, very roughly speaking, two generations of performers represented in the album. For the younger generation, a central point of connection is the crew of musicians who used to manage the now-defunct alternative jazz club Kék Ló and who currently manage the events at the club Tütü Tango and organize the annual Avant-Garde Jazz Festival there in late December. The drummer Mark Gasner is a particularly salient connective node, having recently celebrated his 28th birthday with a 10-hour performance playing with seven of his bands in a row, two of which are included in the compilation (Deus Ex Quartet; Kinetic Erotic). Another meeting point for the younger generation of alternative jazz musicians, but also a few older ones, is Acoustic Manual Techno Sessions; it’s a crowded ensemble featuring a an evolving cast of jazz musicians, which originated from the idea of simulating electronic party music with live instruments, with a result that resembles krautrock. They are not included in the compilation only because they are mainly a live phenomenon and have not released any recordings so far. As for the relatively older generation, larger ensembles like Qiyan and Decolonize Your Mind Society serve as important connecting points; they would be called ‘supergroups’ if it was not a rather ordinary thing for this type of scene that its seminal members frequently team up for new projects.

Besides Tütü Tango there are several alternative clubs in Budapest such as Gólya, Auróra, Gödör and Három Holló alongside a few relatively mainstream venues like Opus Jazz Club which occasionally host alternative jazz events, but two venues need to be particularly mentioned as centers of the scene’s live activity: One is Lumen club, the live program of which has for years almost exclusively focused on experimental jazz, mainly as a result of the efforts of Dávid Tamás Pap who is a promoter, DJ, sound engineer (credited three times in the compilation) and who is also the person behind PrePost Records. The other one is the newly emerging Dobozi 21, a community center and art gallery which is managed, among others, by the surrealist director Nándor Hevesi (one half of the pseudonymous Buharov Brothers) who is also member of Gentry Sultan, one of the most colorful and eccentric ensembles in Budapest that presents in a distilled form all the musical and artistic elements that the alternative jazz tradition has been in conversation with. It should also be mentioned that Nándi has also inadvertently played a role in the process that led to the inception of this compilation: I got one step closer to the world of alternative jazz in Budapest after becoming neighbors with him in 2019; our acquaintance began when I knocked on his door one day, introducing myself and asking him whether Gentry Sultan would like to replace a band that had to cancel a show I booked for them in a small town in Slovakia.

I believe that ‘The Underground Jazz Scene in Budapest Today’ does reflect the diversity of this scene and many of its most central musicians and acts, though naturally there are important things that couldn’t make their way into the album due to the usual difficulties that arise when one attempts at documenting a phenomenon in the most comprehensive way. Making a compilation is a form of making music: Instead of organizing sounds into songs, one is picking from a pool of whole chunks of sounds that are already organized into songs by others, and assembling them into an album that hangs together as a coherent piece of art; instead of writing lyrics that convey a meaning, one attempts at conveying information about a scene, about the spirit of an era. And as it is also the case with writing and recording music, creating a compilation is subject to external factors that set limitations to it. One factor is obviously the social or human factor: an artist cannot be included in a compilation if they are uninterested, unresponsive, uncooperative, or the copyright holder is unwilling to grant permission. In the case of this compilation, a mixture of the above reasons indeed prevented the inclusion of one track from a seminal band of the scene. The other human factor resides on the side of the compiler: one has limited time, energy, and patience to find out about and go through hours and hours of recorded material. There is also the issue of finding the balance between curating a collection that would provide a concise musical statement that can be enjoyed in one sitting from beginning to end, and documenting as much as there is or needs to be documented. For such practical reasons, I had to exclude several important contemporary formations, delineated the regional focus as the city of Budapest as opposed to the whole of Hungary, and also decided to entirely leave out the most established jazz musicians who began their career in the 80s or before, even though many of them are still active and collaborate with the younger generations. The issue of the album length also affects the song choices and leads to some bands’ not being represented by their most typical work: pieces by Bujdosó Trio are often multipart compositions with long solos, unlike their very brief (but complex) jazz punk explosion that opens the compilation, and the seven-and-a-half-minute juggernaut by Qiyan is a dwarf compared to their usual pieces which are much longer narratives that alternate between tightly executed traditional Sephardic melodies and adventures in collective improvisation that can go up to 25 minutes.

As another decision made in order to narrow down the scope, I have categorically left out the recordings by free improvisation formations, even though they constitute a very lively sub-scene, complete with the organization Jazzaj which regularly curates free improvisation events and the aforementioned label PrePost Records run by Dávid Tamás Pap where some of the improvised fruits of this sub-scene are documented. As Dávid writes in his review of ‘The Underground Jazz Scene in Budapest Today,’ the album is a “diving lesson” into Hungarian jazz, but it’s only “the first lesson”. I agree with Dávid that even though the selection would likely challenge the average jazz listener, those who are already deeply immersed in the realm of free improvisation might find it not challenging enough. However, my opinion is that the more unique and striking examples of the Hungarian jazz scene, and perhaps any jazz scene, are more often found among the composed or structured pieces, as so-called “free” improvisation actually has many limitations. The spontaneous composition format is technically closed to certain structural possibilities; moreover, leaving aside exceptional bands that have developed their idiosyncratic dynamics of improvisation, it’s hard for free improvisers to avoid falling back on various conventions of their background genre while trying to create a simultaneous composition in a collective manner. Such limitations can also be observed in improvised psychedelic or experimental rock. Even though with Hayvanlar Alemi we spent our first years as a purely improvisational unit and reached a point where some free improvisations were barely discernible from composed or pre-structured pieces, we eventually had to move towards other avenues to explore after getting too close to the technical boundaries of what improvisation can allow and the whole experience started to feel less adventurous. The guitar-drums-electronics trio 12z, which shares two members with Decolonize Your Mind Society, is the only free improvisation unit that I have included in the compilation in order to hint at this sub-scene in Hungary. It’s a band that can indeed craft distinctive improvised compositions that challenge the above-mentioned limitations and refrains from falling back on usual conventions.

Below you will find interviews with the members of six of the twelve ensembles that contributed to the collection: Sauropoda, microdosemike, Dorota, Attila Gyárfás Trio, Czitrom & Porteleki, and Qiyan. Besides inquiries into their music and their background, I also posed them questions that would help me fill in the gaps in my knowledge about the local alternative jazz scene; about its history, sociology, and how it relates to other genres such as alternative rock and folk.

Interview with Sauropoda

Can you tell us about how the trio began and the projects you were busy with before that? Your music has an equal distance to progressive rock and experimental jazz; did you initially move towards jazz from the direction of rock, or was it the other way around, or was it through a third way? And how did you come up with the band’s name?

Domokos Krizbai: The band formed as a duo in 2018 with Péter Lukács (drums), we’ve met and studied together at ETÜD Jazz Conservatory. Shortly after, in 2019, Zsolt Vaszkó joined the group on bass (in 2022 our ways separated with Zsolt, Levente Kocsis took his place). Before Sauropoda, Péter was drumming in several jazz formations (e.g. Grencsó Kollektiva), Zsolt played in an experimental hip-hop/ jazz band (titokzatostelepesek), Levente is the longtime bassist of the experimental pop band OddID, and I had a solo project called Antropomorf and an avant-garde duo (Pseuduo) with the vocalist Júlia Szirmai.

In the first years, we further developed ideas that came from the solo guitar project. It was partly melodic loop and partly noise music, so maybe this kind of duality might have originated from the core. We shared the common interest to mix different genres and musical approaches from the very beginning. It seemed interesting for us to explore various styles and methods, and not stay stuck at one attitude. As our music evolved, we leant toward heavier tones and accents. None of us would have thought that we would do this kind of heavy music, but I think we found the sound that was inherent to us and we’re still building our musical landscapes and stories in that manner.

In retrospect, I’m very happy about this, because it goes well with our name! This is our name simply because of my fascination with prehistoric animals. I still don’t know if the name led us to the heavy sounds or the other way around, but there is no doubt that our music has some primal animal aspects.

“It seems that it doesn’t matter “how clean is a genre” for the audience”

A related question is about the background of your local audience. For the average jazz listener your music might be too heavy or “guitary” at times; while it might be too jazzy for the average alternative rock audience; not to mention that there is a general decline of instrumental music in the realm of rock. On the other hand, your concerts are often well-attended. According to your observation, from what backgrounds does your audience come from, and does it require hard work to find the right audience given the circumstances and the hybrid nature of the band’s music?

Domokos: I like to think that we play music which is open to everyone. “Jazz listeners” tend to like us because even though we’re not playing strictly jazz, we’re using several harmonical and rhythmical elements borrowed from the genre. As Dávid Pap has said “one thing is certain: jazz is not necessarily a genre, but a musical attitude, thinking and toolbox.” Last summer we played at Fekete Zaj Festival which is based mostly on metal and rock music and to our surprise as well, the “metalheads” liked our music too!

It seems that it doesn’t matter “how clean is a genre” for the audience, they’re in for the weird, intriguing compositions and unexpected musical moments. The “right audience” is listening carefully and focuses on the music regardless of any genre. Lately, our sound is inspired by modern progressive and math rock, and we ventured to a more rhythm-based direction – so a different pool of listeners started to attend our shows. If we ever play synth-pop, I guess it will change again!

Are there particularly identifiable sources of inspiration behind the oriental melodic elements in your songs?

Domokos: It’s a mixture as well, but Jewish, Arabic and Turkish music is definitely in the center. But as I mentioned before, we’ve gone far away from where we started. The melodic aspects are being pushed more into the background. The atmosphere and rhythmic movements emerged as the “main story tellers,” and we’re using mostly uneven time signatures heavily influenced by these oriental styles.

This compilation makes an attempt at capturing the Hungarian underground jazz scene, and indeed most of the bands in the album have played at one point or another at the annual avant-garde jazz festival in Budapest. But it’s of course a different matter whether the performers themselves see themselves as belonging to a “scene” of some sort. There are lots of personal connections that can be observed among the bands. For example, some of you also play in “The Acoustic Manual Techno Sessions,” a loose formation which can be described as “improvisational krautrock for dance parties” (for the lack of a better term), and other regular performers in that formation come from bands such as Deus Ex Quartet, Kinetic Erotic, and others. There are similar connections between many other bands in this compilation, and almost every individual musician can be linked to another with very few degrees of separation. In your opinion, to what extent is this a result of having a coherent, well-developed scene with musicians that share similar musical visions, and how much of it is a result of the opposite, that is, friendship ties playing a big role in the formation of ensembles due to there being a relatively small pool of performers? Do the musicians represented in this album ever think or talk of themselves as a scene?

Domokos: Both are true actually. We’re working together, we share a musical vision, in a way, we all carry this kind of thinking of music and attitude of playing. As a quest, we’re trying to share it with a broader audience. We’re contemporaries, we’re friends which bonds us together even more. We do talk about ourselves as a scene. A very wide and versatile group of musicians who decided to make music which dares to take risks.

Not long ago you played a concert augmented with a brass section. Should we expect some recordings from Sauropoda in the near future that are in that vein? If not, what’s on the way from Sauropoda and the other projects of the band members?

Domokos: Yes, you should! We have just published the concert film with the brass section. They are all new songs and are not on any album yet. We really liked the brass concept. It was refreshing for the trio to expand the sound and we will definitely do it again! We’re slowly finishing our EP as well, but shss! – it’s a secret.

Interview with microdosemike

Let’s begin with the story of the band: How did the band members get together around the idea of playing this music? What other musical projects or backgrounds do the band members come from?

microdosemike: Everyone already knew someone from the band somewhere. We started from Dürer’s cellar, jammed in Pécs with Csabi, and that’s how we got to know each other. Our previous bands include Kacagó Gerle, Drugi Program, Los Babaz, and Kerekes Band.

Compared to the other bands in the compilation, microdosemike is situated in a somewhat different local musical context. You do have some connection to the local alternative jazz scene but do not seem to identify strongly with that category. Your debut album was recorded by Bence Ambrus from Psychedelic Source Records, the main outlet in Hungary for psychedelic rock and jam bands, and you also appeared in a compilation from that label; on the other hand, you are also quite distinct from the rest of the bands in the Psychedelic Source catalogue. Where do you situate yourself in the local and the global music scene?

microdosemike: It’s challenging to determine which musical style or genre we belong to. We enjoy performing with various bands. We don’t really fit into any one category, as none of our members are trained musicians; each follows their own taste, and these tastes blend together. There are no learned templates to adhere to in any specific genre.

Your tracks are relatively long, with intricate structures, and a very generous use of melodic themes; each track feels like several different songs could grow out of them. How does a microdosemike song come into existence?

microdosemike: During the creative process, someone brings up a theme, and then we continue together, reacting to it and adding what appeals to us. Sometimes a whole song is born from a single theme, but other times, the initial theme serves as the introduction to a new song. We listen back to themes born during jam sessions and further develop them. Some places are kept as improvisational spaces. There are no predetermined templates or fixed stylistic directions. What excites us is that the creation can go in any direction.

“Budapest is a melting pot where we can easily access Balkan, Gypsy, Jewish, and Hungarian folk music through live performances”

The prevalent themes in your pieces are Middle Eastern and Balkan; is it possible to pinpoint more specific regions or origins for the melodic and rhythmic elements in your music? Also, how much of a role does Hungarian traditional music play in your songs? Some say that many young people in Hungary started to be more interested in the folk music of Hungary only after the global popularization of Balkan music in the 2000s. Is this true?

microdosemike: Budapest is a melting pot where we can easily access Balkan, Gypsy, Jewish, and Hungarian folk music through live performances. Many people are experimenting with these musical elements nowadays.

In a concert a few months ago at the fundraising festival for Tilos Rádió you played a set of completely new songs. How do these differ from the older ones, and will we have the chance to hear them soon in recorded form?

microdosemike: New songs are constantly being born, and as soon as we have some semi-finished pieces, we incorporate them into our live set while continuing to work on and shape them. Our new album titled ‘Ekhidna’ came out in November.

Interview with Dorota

I would like to begin with the history of the band, the outlines of the music that you do, and your individual backgrounds, but in an interview with this magazine two years ago you already talked about these quite a bit [interview from 2021 here]. Can you summarize the basics for the readers who might not be familiar with Dorota, and also tell a bit about the developments since then, such as your new EP titled ‘Good’?

Dávid Somló: We went through quite some transformations, while the core of our musical approach stayed the same. We started off as an instrumental experimental rock band with inspirations from free jazz through repetitive music to surf rock, while the ethnic elements of all regions of the world were always present in our sounds.

After our first untitled album, we went on a crazy journey of creating a conceptual creation that started off with some Nigerian scam letters I’ve received, ending up with a whole fictional story of trying to climb a non-existing mountain. This creation consisted of three albums of musical material intertwined with hours of experimental videos and texts, all put in an interactive website. It was not an easy piece, but definitely exciting.

This process really tested our strength, so we decided to give it a break. After two years and a messy but highly energetic support concert, we’ve decided to apply for a grant for a new album – we already had a title. We decided that we only do it if we get the support. We got the grant so we rented a large house and wrote and recorded our 3rd album ‘Solar The Monk’ in 10 days, which is our most successful creation yet. With this album we wanted to try a more straightforward songwriting and we also started to sing – more of an ethnic-hardcore style men’s choir. The album is kind of a mix of punk-hardcore with North-African and spiritual musical elements. This type of music needed a different live approach, so in a few months we developed from a band mostly playing completely free improvisation to a 4-7 piece rock band with a lot of ritualistic elements.

‘Solar The Monk’ was widely acclaimed and we started to receive great opportunities to tour in France, Armenia and Russia, also to record with the artists from the Caucasian Ored recordings. These opportunities were unfortunately all washed away with Covid, and halted our momentum. We also had a lot of changes in our personal lives and the continuation as a functioning band became more and more challenging. In the meantime, as a way of moving on we tried to write and record the album which became the ‘Good’ EP, but it was a very difficult process. Last year we decided to have another break, but from the already recorded material we created ‘Good’, which is a highly personal album for us, and we are quite happy with the journey it creates for the listener.

“We were never really attentive where our music originated from”

When listening to Dorota one feels a similarity in spirit with a loosely-knit scene in the 2000s in USA, sometimes referred to as “Free Folk” or “New Weird America,” which consisted of a hard to categorize mixture of experimentalism, improvisation, psychedelia, drone, lo-fi aesthetics, and folk-ish elements that often came with tribalistic or primitivist overtones, and it is also possible to feel a similarity to various moments of Sun City Girls which foreshadowed this scene. Around that time there were also similar trends in various European countries such as Finland, and Hungary also has its own history of mixing psychedelia, ritualistic music and punk that goes back to late 80s, exemplified by bands like Korai Öröm and VHK. Is there any organic connection between Dorota and any of the above-mentioned currents?

Áron Porteleki: I think we were never really attentive where our music originated from. With Dani we were listening to a lot of French free jazz, different folk musics, then put that away for a few songs of Police or Jethro Tull even… My other side is a huge Stones and Zeppelin fan, while in my teenage years going to school with a cassette in my Sony walkman that has ‘Life is Peachy’ [by Korn] on side A and some archival folk music recordings from Transylvania [a region of Romania where Hungarian rural musical traditions are well-preserved] on side B was totally normal. So I wouldn’t say that we were focused on any genre or concept, but it’s true that we had immediate arguments about how we should sound when we first got together. What was common among us and was really forming our albums were more coming from movies, books, and stories around us. But let’s narrow it down and say that bands that were hard to define in sound or were raw enough to be useless for any categorization was a thing for us for sure. Also any trippy thing, but we could find it in a lot of genres, not only the ones that were dedicated to it. I personally never listened to Korai Öröm and was not a big fan of Hungarian psychedelic attempts or the so-called underground.. Except VHK, which I was a huge fan of (and still is), and we even tried to contact the frontman Attila to make a collaboration together. He was open to it as I remember, but we never made it happen, and later when we were invited to cover a song from them on a VHK compilation, we turned it down unfortunately for various reasons that arose within the band. It would have been fun though, and I would love to listen to a VHK cover from Dorota, or vice versa (haha). As for the issue of sound: I think the raw sound is a common thing in Eastern European bands of that time, maybe it is due to the fact that it was hard to get good instruments, equipment, and a lot of the demos and albums were lo-fi, on the spot and live recordings rather than hi-tech studio productions. These bands had a very “true” atmosphere, and also carried a lot of meanings which could be common in these areas such as Hungary.

A rather specific issue, but, there are quite a few people in Hungary who are interested in Indonesian gamelan music and have played in gamelan orchestras, including at least some (or all?) members of Dorota. Is there any particular reason why gamelan is big here, or maybe I am just underestimating its global popularity? And what personally attracts you in gamelan music?

Dániel Makkai: I encountered gamelan music thanks to my friend Marci Szatai (who played Solar the Monk’s material with us many times in the past years). Between 2010-2013 I played in a Budapest based band called Surya Kencana A, founded by a nice community who were studying music in Indonesia with a scholarship. Since then, several other members of the group have gone to Indonesia to study gamelan, and international collaborations have been formed, so the band has grown a lot. My most powerful musical experience is connected to gamelan. I was fascinated by the altered state of consciousness while playing it. I was definitely searching for this immersive existence in playing music so it showed up in Dorota somehow, not in a concrete musical form, but rather in a way of thinking. Áron and David had the same influences from other musical experiences that we merged in Dorota.

There is a visible interest in traditional non-Western musical elements in the more experimental corners of Hungarian music; however, it is relatively uncommon in such corners to come across works that carry elements of traditional music of Hungary, at least not so saliently. Some people offer a socio-political explanation to this, saying that interest in local traditional music was discouraged to some extent during the communist era as it was associated with nationalism and consequently it was indeed nationalists who embraced traditional music more, and so even until recent times this made many liberal or left-leaning musicians and listeners distance themselves from traditional music to some extent; whereas we find the opposite situation in some countries with different socio-political histories where left wing ideas drove people towards folk music. Is there any truth in this historical explanation, and to what extent does the traditional music of Hungary inspire the music of Dorota?

Áron: In 1984 I was born into the then roughly 10-year-old Hungarian “Táncház” movement [“Dancehouse,” the name for traditional folk dance parties that were revived in the 70s]. It was still a very diverse group of people including artists from different fields and interests, and of course ethnographers and music ethnologists, and also just urban people who sought some raw, lively, true feeling of community. It was of course also a form of resistance in that political era, and a communist leadership couldn’t really put their finger on these “folk guys”. They were “just” singing, and dancing, and playing this music, while through the traditional lyrics of these folk songs for instance people of this community could really express their feelings about those times, oppression, sadness, hopelessness, helplessness… It was a good trick. It was not about nationalism or at least it was not the goal I think, I remember these people to be very open minded and respectful towards other cultures, history and people. It was also very important since they were also inhabiting and transforming another kind of Hungarian culture they found mostly in the Hungarian parts of Romania, where local traditions were still very alive, compared to Budapest and most of the mother country. I think it was a bit later after 1989 [the year of the regime change] that the whole scene became frustrated, and couldn’t face the fact of globalism, world music, and then it got worse when Hungary became one of the basecamps of this populist shit which is going on right now, and which can really get support from the right wing and nationalist ideas. Therefore a tradition like “Táncház” and all this neo-folklore and revival thing can be a beneficial thing to ride on… So until recent years it was really not sexy in many leftist communities to show any like or interest towards Hungarian folklore, attend events; also it was heavily used in the government’s communication, in television. It really feels that you can only win an application for instance in music if you have something to do with folk music. It built so much hatred towards it, while inside the “dancefloor” and amongst the people who are still doing it as a profession, there are still interesting things going on. And also true that in recent years people who were never in the community started to take back Hungarian symbols, traditions, customs and try to find their own connection towards it without any ideological concept or revisionist belief. So nowadays it is more clear I think what went wrong, and this community is a bit maybe more diverse again or at least there is space again..

What is the connection with Dorota? Well, the whole problem is very interesting for us, so there’s plenty of entry points if you are seeking inspiration when creating music. As Dorota we never used any concrete folk theme, but I think the sounding of the archive recordings, the characters of those folk bands, and how they produce sounds on their instruments, the rawness, and complexity, and the strange, almost alien virtuosity with such simple elements were really a heavy inspiration on our music. And also the fact that how far we are from these dimensions of our own culture.

Dorota’s music is full of unpredictability and it is constantly changing, and one wonders where it will go from here. What are the band members busy with nowadays, and have you tapped into new sources of inspiration or made new ethno-musicological discoveries? Should we expect a new release from Dorota in the foreseeable future?

Dávid: I am focusing my energies on my solo work: I am creating and touring with performative and site-specific pieces based around sounds and human interactions. I am also researching this topic as a PhD candidate and teaching performative practices at the Free University of Theatre and Film, Budapest. On the side I am Dj-ing African music under the moniker of Dr. Somolo. At the moment I have stopped playing any instrument regularly.

Áron: I was kind of left stuck for a while when it turned out that as Dorota we can’t go on, at least for a while.. But it also opened up a big space in front of me, and I also realized that I still have so many musical ideas I’d like to work on. Since I’m the only one in the band that literally lives from music and playing gigs, forming different long or short term bands and musical projects will be a thing for me forever I think. With this new time though, I managed to tap into my own ideas more, and started to develop some solo stuff, which will be released in march 2024. My other leg has grown from somewhere there, since for 10 years I’ve been working with contemporary dancers, performers, choreographers, and this field is still very fueling for me. I make 2-3 scores for every year, then also tour with those groups. That is really a different mindset than sitting behind the drums in a band, and I’m really grateful for that, and learned a lot about equipment and software there. Working with dancers allows for a very different approach in creating, which opened up new possibilities for me about my music projects as well.

Dániel: I’ve mostly worked with children and I’ve always had less energy for Dorota. Now I work in the field of child protection with an NGO helping Ukrainian refugees. I have been very busy with my job for the last two years, but I am looking forward to the moment when music can come back into my life. There is no question that I will make this space for music above all for Dorota.

Interview with Attila Gyárfás Trio

Among the bands featured in the compilation, Attila Gyárfás Trio (which is indeed a quintet in that track) is the only international band, and the track was not recorded in Hungary but in Amsterdam. In what circumstances and with what kind of shared musical interests did this ensemble come together? In general, how strong are the ties between experimental jazz musicians in Hungary and those in the rest of the world, especially the rest of Europe, in terms of being aware of each other’s music and collaborating on projects?

Attila Gyárfás: Bassist Marco Zenini, guitarist Márton Fenyvesi and I became close friends and started making music together during our studies in Amsterdam. We developed mutual trust towards each other’s musical decisions, even though we come from different backgrounds. Playing with Márton and Marco has been very liberating and they have inspired me to look for sounds and to welcome musical situations that had been unknown for me. The recording session with saxophonist Felician Erlenburg and clarinetist Jason Alder was the first and so far the last time this quintet has played together, except for a brief performance at the concert hall of the Conservatory of Amsterdam. It was uplifting to experience how easily the music released on “Cloud Factory” came to life despite the fact that some of the members didn’t even know each other before the recording session. As a consequence of the efforts of organisations like the Budapest based JazzaJ and labels like Inverted Spectrum Records it becomes easier to connect improvisers living in different countries with each other and with foreign audiences. The difficulty is that the strongest way of experiencing this type of music is in a live setting and the financial conditions often make it impossible for musicians to travel and perform abroad. I wish there were more exchange programmes between venues of different countries.

The trio has not been active for a while, but you personally have various other projects going on, can you also tell us a bit about those?

Attila: Less than a year ago I released a drum solo album named ‘Minimal Distance’ and I played several solo concerts in the past months. I am currently working on my second solo record. I started an electroacoustic duo project with composer Bálint Bolcsó with whom we recorded an album entitled ‘Tabbis’ that consists of improvisations, each of which reflects on particular poems written by Mihály Babits. I co-founded a project named Identified Flying Object with Belgian-Japanese pianist Alex Koo and launched a group called Quelquefois with some of Hungary’s finest improvisers: Bálint Bolcsó, bassist Péter Ajtai, and saxophonists Gergő Kováts and János Ávéd. I have been collaborating with Gabriel Zucker, a pianist and composer based in New York City. We have had several duo tours in Europe and we have just recorded our second album. I play in a new group called Kovász, with which we blend Hungarian folk music with free improvisation and other genres. I play in the band named three initiated by visual artist and musician András Wahorn, and I’m a member of the Filippo Vignato Trio and the Athens based Grigoris Theodoridis Trio.

Even though it’s more common in jazz than in other genres, it’s nevertheless relatively rare for drummers to be bandleaders and primary composers of a band. When composing the melodic and harmonic elements of a piece, do you compose on some other instrument or use notation, or is there also a broader sense of composition involved here, where there is a general idea and structure from which the individual instrumentalists develop the details?

Attila: I usually compose on the piano but I wrote most of the etudes released on ‘Randomity’ using a pocket synthesizer. I prefer to let musicians interpret the precomposed material their own way and develop personal connection with the compositions, and I am currently working on exploring further possibilities that can be derived from this basic concept. I was commissioned to put together an ensemble for a concert at the Budapest Music Center, and I invited legendary flautist Magic Malik and two improvisers from the Hungarian scene that I feel very much connected to: pianist Máté Pozsár and bassist Ernő Hock. I decided to bring incomplete compositions that contain a limited selection of musical elements (for example only rhythms and key signatures without melody, only key signatures and melodies without rhythm, or only rhythms and chords without melody), so the musicians had to improvise the missing elements. I believe the resulting music was exceptionally fresh and I hope to share the recordings of this concert with the public.

“The etudes are meant to guide the trio towards the idea of playing like one instrument that has three voices”

The second album of Attila Gyárfás Trio, ‘Randomity,’ is more abstract and minimalist than the first one, with pieces divided into two categories, very short “etudes” and slightly longer “improvisations,” consisting of fleeting ambiances and small improvisatory variations on compact themes; and the listener is instructed to listen the tracks in shuffle mode. Can you tell us about the idea behind this album?

Attila: In the period preceding recording ‘Randomity’ my attention shifted towards texture based collective improvisation. I had a vision according to which playing very short, totally precomposed pieces that mostly deal with rhythm and melody would evoke greater amount of freedom while recording improvisations without any restrictions. The etudes are meant to guide the trio towards the idea of playing like one instrument that has three voices. After the mixing session I spent several days trying to come up with the perfect order of the 20 tracks. I soon realised that any order can work and that it is much more enjoyable to play the album in shuffle mode because the record will have different shapes every time one listens to it.

Is there an organic connection or continuity between the current generation of free or experimental jazz musicians in Hungary and the generation of musicians exemplified by those like Szabados, or is there also an unconnected strand of experimental jazz musicians who came from a very different background? How strong is the effect of the history of Hungarian jazz on the fact there is a quite productive experimental jazz and free improv scene in Hungary today?

Attila: The current scene of experimental/improvised music in Hungary is not huge, therefore musicians from different generations often perform together. This embraces transferring tradition and also gives opportunities to newcomers on the scene. Openness is an important factor in this music, and I love the fact that musicians coming from very different stylistic backgrounds (classical, noise, jazz, punk, metal, folk, et cetera) are able to make music together. I believe that if one lives in Budapest, has a vision, and puts a lot of time and effort into mastering his or her instrument while having a passion towards this type of music, it becomes rather difficult for him or her to stay disconnected from the improvised music scene of Hungary.

Interview with Czitrom & Porteleki

How did you two (Ádám Czitrom and Áron Porteleki) first get together to play?

Ádám Czitrom: We had been aware of each other for a couple of years before actually working together, which of course, is no surprise considering how close-knit the Budapest music scene was and still is. It was early 2013 when the two of us were called on to co-create and compose the music for a contemporary dance performance called Skin Me. It ran for nearly three years in the course of which time we started to perform as a duo independently. Though I have always been infatuated with spontaneous music making, it was the duo that truly marked the beginning of my turn towards free improvisation.

Your music falls pretty much into the category of experimental jazz, but there is also something in it that is not fully captured by the tag or evoked by its usual associations. How would you describe your music to someone who hasn’t heard it?

Ádám: I’m usually reluctant to describe our music in terms of style. I guess the indeterminacy you’re implying is actually what we were aiming for. Our rehearsals were very much a workshop into which we channeled whatever interest we had at a specific time without being too self-conscious about whether or not what we play is “idiomatically adequate”. I think our commitment has to do more with working from within a mode of spontaneous storytelling. So, as long as this question keeps coming up as unresolved, I believe we’re doing our job…

You two also play in projects which are more in the realm of experimental rock, alternative rock or post-punk (such as Dorota, Siketfajd, Jazzekiel, and others). There are quite a few other musicians in this compilation that have a similar versatile profile. Do the audience members in Hungary have the same cross-genre flexibility or versatility as the musicians? When you perform, do you see faces in the audience familiar from your other projects from different genres?

Ádám: Sure, there are recurring faces. Cross-genre versatility is one way to think of it, though there is a great share of common ground between the genres you have listed, especially when it comes to live events. There is an experience of a “here and now” shared across various styles of creative music that, I believe, the audience is responsive to on a much rather intuitive level. I can recall a relatively late interview with Coltrane in which he was asked about the various stylistic stages his music had gone through, to which he replied he had no idea about any of these, and I paraphrase “as far as I’m concerned, I was doing the same thing all along”. So I guess it’s pretty similar on our part as well, we’re essentially doing the same thing.

“I think the very limitations of that era gave rise to some very authentic creative efforts”

Several years ago Ádám published an album with Benedek Darvas where each song is written in the style of a specific alternative rock band from Hungary from the older generation. Even though the album is conceived as a “musical caricature” as written in the liner notes, it is also stated that these are the bands you like. What effect, if any, did the 80s and 90s generation of alternative rock and post-punk bands have on the creative music of today, both in sound and spirit, including on the more experimental music?

Ádám: My exposure to the Hungarian alternative scene of the 80s came relatively late as I didn’t grow up here. After graduating from high school here in Budapest, I saw the band Balaton at Gödör Klub and I couldn’t really decipher what I was witnessing. It sounded like some sort of Eastern European blues that was peculiarly reserved and melancholic. The whole atmosphere of that concert and music was unlike anything I’ve ever heard earlier. That was around the time I also met Darvas owing to whom I became more affiliated with these bands. Although Hungary was pretty much cut off from what was happening in CBGB et cetera, there was just enough leakage of creative music to get the ball rolling and inspire artists to experiment with new ways of expression that didn’t necessarily require professional training (though there were many trained musicians too on the scene). I think the very limitations of that era gave rise to some very authentic creative efforts that were as important socially as they were aesthetically. I don’t know how much of this ethos lives on today, I wasn’t there in the first place, but from what I hear from older musicians, there are some bits and pieces of it still in currency.

Both of you have rather idiosyncratic ways of playing your instruments. Were there ever particular drummers or guitar players that were influential in the formation of your style when you took up your instruments a long time ago, or perhaps at other points in your musical career?

Ádám: Well thanks. There are so many. I don’t even know where to start… I probably listened to more instrument-specific players in my teenage years. Now I tend to just listen for sounds that I find exciting regardless of instrument or style. I can listen to the mixes of Chad Blake on the same level I listen to Bill Evans’ playing, I guess… In terms of jazz, I’ve been listening to a lot of Wayne Shorter, Elmo Hope and Henry Threadgill. I really admire Mary Halvorson both as a guitarist and composer. I recently got to watch the documentary about Milford Graves (Full Mantis), whom I’ve been obsessed with for a couple of years. At festivals, I always end up at some techno party. Recently I’ve been into hardcore. There are some really exciting and intense events happening around that scene here in Budapest. Not sure I’m allowed to name the clubs (lol…)

The duo plays rather rarely these days. Do you have plans to play more or record in the near future?

Ádám: Not as of now, but we do play together in other bands, i.e. Qiyan. In November we played in a new band at the reopening of Merlin club in Budapest.

Interview with Qiyan

How did you come up with the idea of a band that plays songs that alternate between free jazz and very melodic sections of Sephardic music? The other members of the band are also established musicians from the scene, what makes them come together for Qiyan?

Péter Ajtai: I had long been interested in doing something about the connection between my Jewish roots and music. I had played Ashkenazi music in several bands, but I felt that John Zorn and the New York schools had basically done everything with that. I was looking for something else. Part of that is that one of my grandfathers was an ambassador to Cuba, so that part of my family speaks Spanish, and I’ve always been involved in Spanish culture. That’s how the idea of Sephardic free jazz came about, inspired by different types of music I heard as a kid and YouTube recordings I found.

My fellow musicians in Qiyan are my friends. We are bound together by our love of creative music and curiosity about other cultures. I come up with the ideas, but we always make the pieces together.

“The origin of the songs is very obscure”

Can you tell us about the history of the traditional tunes that form the basis of Qiyan songs? Were these melodies preserved mostly as they are since the time of Iberian Jews, or did they take shape after the expulsion, in centers of Sephardic culture such as Thessaloniki?

Péter: The origin of the songs is very obscure. Some of the songs originated in the Cordoban Caliphate, where Arabs and Jews and Christians lived in peace. Other songs were born and spread in Europe during the Exodus. There is also a tune that is recognizably based on a Viking song, probably brought to Spain by northern pirates. We are dealing with Ladino, Sephardic Jewish songs, but for example on the second album there is a song that comes from Transylvania.

Qiyan songs are often very long, sometimes above 20 minutes; they have complex structures that alternate between the traditional, melodic sections, free improvisation, and moments of transition. How does a Qiyan piece come into existence?

Péter: A piece usually comes about because I’ve been singing it for months, and then I imagine some kind of structure or idea for it. I take it to rehearsal, and we work out these ideas with the orchestra. What’s very important is that we take these songs and take them apart and put them back together again from bits and pieces. It’s processed music, so the narrative in which we perform them is very important. As such, that’s why these songs are usually long.

Similar to some noise rock bands, Qiyan often plays on the ground level rather than on the stage, forming a circle or a semi-circle. Is this a purely practical choice arising from the size of the band, or is there some other idea behind it?

Péter: The original idea of the band is based on playing the music of the Qiyans, the Jewish female slaves of the Cordoban Caliphate. They were basically poets. By being in a circle we might be giving back some of the spiritual power of these songs. However, by being close to the audience, we may also be able to create an act of community building, which is also the band’s unhidden intention.

In today’s socio-political circumstances with growing far-right sentiments and a rise in direct or indirect expressions of anti-semitism in Hungary and other parts of Europe, is there a political statement of defiance involved in playing Jewish music? Or would you rather prefer that a listener perceives Qiyan’s music as a purely musical experience, that is, something that is best appreciated when isolated from such societal, political or historical matters?

Péter: On the one hand yes, on the other hand no. Of course, it’s always interesting to play Jewish music in a far-right environment, but it’s very difficult to say what the current government’s attitude is towards Judaism, and Hungarian folk music culture is so intertwined with Jewish and Gypsy music that it’s hard to separate them. What’s interesting for me is that we play music that is a common Arabic and Jewish melody from the peacetime era, which is mostly a reaction to events in the Middle East. Especially after the events of the last few months, which have happened and after which I just don’t understand how the world works anymore.

Are there any new recordings of Qiyan on the way, and what are your other current projects besides Qiyan?

Péter: Yes, I’m working on our new material. It’s going to be a bit more different than the previous ones. One part is a Shostakovich interpretation, and the other part is Sephardic music. Besides Qiyan, I have a Charles Mingus Project and several free jazz bands of my own – Peter Problem for example, but I also play bass in several bands. I also teach and am a music columnist for a Hungarian cultural portal.

Inverted Spectrum Records Facebook / Instagram / Bandcamp

Information about the personnel and the social media links for the interviewed bands can be found in the liner notes of the compilation.

Great article, are any of these bands playing this month?