5uu’s | Interview | David Kerman

David Kerman, the drummer-composer behind the avant-rock group 5uu’s, has made significant contributions to experimental music since the mid-1980s.

His band, 5uu’s, was influenced by the European Rock in Opposition (RIO) movement and collaborated with other avant-garde groups, blending complex compositions with a rock sensibility. After reuniting with the 5uu’s in 1994, Kerman embarked on various projects, contributing to the revival of the experimental rock scene. In 2022, after a long hiatus, he returned to the music world with a new 5uu’s album, reaffirming his innovative approach to avant-garde music.

“To try and find something “different”

You’re coming from a very interesting background. You were born in Torrance, California, and began playing drums very early on. Keyboardist Keith Godchaux was a family friend? How did he influence you to begin playing drums?

David Kerman: Yes, Torrance: We were spoiled-rotten baby boomers. We were upper-middle-class children of parents who gave us a million miles of leeway and even more support. We were never told that we might possibly fail at anything, so very few of us did.

Keith Godchaux lived across the street. This was in the late 60s, before he joined the Grateful Dead. I was friends with the kids who lived there. We youngsters thought we were alone there one day, so the others egged me on to play the set of drums next to the family piano. I’d never played before, so I beat the hell out of them, like only a nine-year-old could, merely to wake the hippie in the next room, Keith G.

He emerged from what must have been a deep sleep and walked across the room towards the upright piano. I stopped thrashing about, scared as hell to be caught playing someone’s drums. But he urged me on, saying, “Hey, keep that going…I like the beat.” So I did, and he joined in. Can you imagine that? The first time you play your craft is with the guy who would end up doing ‘Blues for Allah’ and ‘Terrapin Station’? He took me across the street and somehow convinced my mother to buy my first set of drums. I owe him a lot, bless his soul, and I’ve never looked back.

Was there a certain scene you were part of? Maybe you had some favorite hangout places? Did you attend a lot of gigs back then?

Well, we were children of Progressive Rock. I came to the Syd Barrett and Captain Beefheart later in the ’70s. I saw Gentle Giant a bunch as a teenager, and that band, probably more than any other, inspired me. Their last string of gigs was at The Roxy, and yeah, that was my hangout. I was there a lot for some years. Cobham and Duke, Genesis, Beefheart, Gentle Giant, Peter Gabriel’s first solo shows, etc. The list could go on forever. Man, it WAS the house.

I had a trick, and the owner of The Roxy knew it but allowed me to pull it off nonetheless: I would buy a ticket for the early show, arrive late, and hide in the men’s room, kneeling on the toilet lid between sets, to get the best seat for the second set. “David, you in there? Need some aspirin? David, is that your cigarette smoke?” I can’t remember his name for the life of me, but that guy booked everything that was cool. Most normally, two pals, Peabody and Muller, would have sneaked in a tape deck—God only knows how—and taken their places at the right upper balcony, condenser mics dangling just below their sneakers. These were great bootlegs, but it was never about money. We were fanboys and traded cassettes. Ah, Roxy, the REAL Roxy, on Sunset.

How did you originally meet guitarists Greg Conway and Randy Coleman? Together, you started your first band. Tell us about those early experiences of making your own music.

We knew one another from school and got hooked on fusion quite early, especially Mahavishnu Orchestra, Return to Forever, and Weather Report. Eventually, Greg and I spent hours and hours with ‘I Sing The Body Electric,’ and Randy and his brother Wayne turned us on to King Crimson when the album “Islands” came out. There was a cornucopia of compelling music back then, and we youngsters wanted to be part of it. Our core was Greg, Randy, Beck, Chuck Turner, and me. And a bit earlier, Juan Croucier, who later joined the big hair band Ratt. Ha, in 1974, as fifteen-year-old kids, Greg and I went to Juan’s house to “audition” him as bassist for our band, only to find him already a maniacally talented violinist, playing along to ‘Birds of Fire’ note for note. A humbling experience, to be sure.

Since the beginning, you were interested in modifying drums and experimenting…

I’ve done all kinds of strange stuff over the years—not to be deliberately weird, but to try and find something “different.” I played a couple of concerts with tuna fish cans filled with nuts and bolts flopping around on the drums and cymbals, kept somewhat in place with fishing line. And whereas a lot of drummers use pillows or foam inside the bass drum, I tended to use junk that would rattle around and be noisy. Sound men (or women) tend to either hate me or be amused by the antics. But there is a method to the madness, as I’m going after a more industrial sound than wonderful, professional frequencies. I’ve impaled bowls of fruit along the edges of cymbals to deaden the ringing sounds, and used Barbie dolls in place of soft mallets. I became pretty adept at decapitating them against the bottom of the ride cymbal at propitious moments, allowing the doll heads to fly into the audience.

It’s all in the name of entertainment, visually as well as sonically, because if nice people are going out of their way to watch you perform, you might as well do your damnedest to give them their time and money’s worth. Most rock drummers have a little bit of Keith Moon in our psyches anyway, or we’d play clarinet or something less abrasive to the senses. As a personal philosophy, I think one can always go overboard and back off a bit if needed. It might require some damage control afterward, but it’s better than not going far enough in the first place.

If we stepped into your teenage room, what kind of records, fanzines, posters, etc., would we find there?

When we were teens, my friend Mike F. came to the front porch one day, clutching an album. He said, “I’m not gonna come in or waste words, but you gotta hear this immediately,” before walking away in silence. It was Il Balletto di Bronzo’s ‘YS,’ an Italian progressive high-water mark, and it remains one of my favorites. My friend Ske thinks it’s the best rock album ever, and I can’t really argue. Mike and I have a great friend, Michael K., who turned us on to a lot of stuff. So, here ya go (you did ask about my teenage room, and my mother gave me a hearty allowance to buy records with, hoping it would keep me in that room and out of trouble).

Led Zeppelin, ELP, Jonesy, Greenslade, Rare Earth, David Crosby, The Doors, The Yardbirds, Steppenwolf, Santana, The Guess Who, Banco, James Gang, Yes, Montrose, The Lovin’ Spoonful, Cream, Blood Sweat & Tears, Hendrix, Gentle Giant, Mott The Hoople, Biglietto Per L’Inferno, The Who, Uriah Heep, The Rolling Stones, Jethro Tull, ZZ Top, King Crimson, Cactus, The Beatles, David Bowie, Aerosmith, The Grateful Dead, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Grand Funk, Masters of the Airwaves, PFM, Genesis, Chicago, Malo, and the beat goes on and on.

Later, still in my teens, Recommended Records came about, to which I was the biggest fanboy. Still am: Univers Zero, Henry Cow, Etron Fou Leloublan, Stormy Six, ZNR, Art Bears, This Heat, John Greaves/Peter Blegvad, Begnagrad, L. Voag, The Residents… for me, comfort music.

How did you get the name “Farmer Fred Genuflects to A-440”? There must be a story behind it?

Heh. We played a Greenpeace festival in 1977 off the Pacific Ocean near San Diego, geared towards the “Save The Whales” initiative. The band was called simply, “Genuflect,” but the concert promoter, Danny Dolphin, mistook the name for “Genesis.” So quite a few folks came to see Phil Collins and the like. We had to be good, and we were. But man, there were disappointed people, at least at first. Luckily, back then, a few spliffs could smooth over the rough edges, so we somehow got them to like us. Also, Danny D. had a second set of smaller PA columns pointed out to the ocean, and—according to him and his confeds—several whales seemed more than usually active, lunging up out of the ocean in joy at our music. OK, cool. But what are the chances that a group of young Homo sapiens playing prog rock on the shore in the ’70s could bring about elation in a nearby species that’s fifty million years old? Who knows, really, because whales are smart.

So, I tried to get smart too, realizing that if you’ve got a band name that even somewhat resembles another’s, you better clear up any misconception ahead of time. So we got all crazy with the band names, and the longer the name, the more I liked it. I got over that, too, when I chose “5uu’s.”

“The music of Henry Cow changed the way I look at things in general”

Would you say that the formation of 5uu’s was directly inspired by hearing records by Henry Cow, Faust, and the like?

Yeah, but the first time I heard Henry Cow, I hated it. At that Greenpeace Festival, some dude came backstage and said, “You guys were good. Not Henry Cow good, but good.” What does that even mean to a sixteen-year-old Yes fan from Torrance? Next thing I know, this bloke has me stoned out of my brain in his Volkswagen Bug as he pops a cassette into the car stereo. That was my initial impression of Henry Cow. First, there was silence. Then there was loud racket, and then a woman shrieked! This shivaree scared the bejeezus out of me, so I quickly said my adieux and hurried to the safety of the backstage. When I told my (older) bandmates that I’d just heard the worst music imaginable and that it was called “Henry Cow,” they admonished me for letting the guy drive off: “We’ve been looking for Henry Cow albums for years, man!”

I was the youngest, the only one with a driver’s license and a vehicle, and there was a bit of gas in the tank. So, I was designated to drive them, albeit paranoid of the North County Sheriffs (because the car was so smoky that I could barely see the road), to inner city San Diego, to Tower Records’ import section. There was the album ‘In Praise of Learning’. We got home with it in one piece. No arrests that time.

From the first few notes, I sank into the couch cushions and received an epiphany. It totally shocked me into place and taught me that I should not grant first impressions any bit of leeway. The music of Henry Cow changed the way I look at things in general, and that’s the greatest compliment I could give anyone. To my ears, they were the finest rock band ever, with intense aplomb, a virtuosity of their own devices, and an unsurpassed vision. I realized how much work must have been put into this album, and upped my work ethic as a musician because of it.

Would love it if you could elaborate on the formation of 5uu’s and how the members got together. What would you say was the main concept behind it?

In the beginning, there were five of us, all with varied musical persuasions. Some of the things we could surely agree upon were drinking copious amounts of beer, improvising, and making a lot of aimless noise. But once I began writing songs, the others took to that vocation also, in their own styles, and were quite good at it. They’ve each continued in that direction to this day. Meanwhile, it seemed natural for me to keep the name and continue doing my own musings.

Over the years, while this particular band has been primarily my personal vision (music, words, arrangements, production), almost everyone else has had their own aspirations, compositions, and indeed their own bands, which I’ve been involved with solely as a drummer. It’s become rather domestic, like taking turns serving Christmas Dinner every year at a different family member’s home. My meals, let’s say, might be the most homespun, whereas the others give us gourmet delicacies.

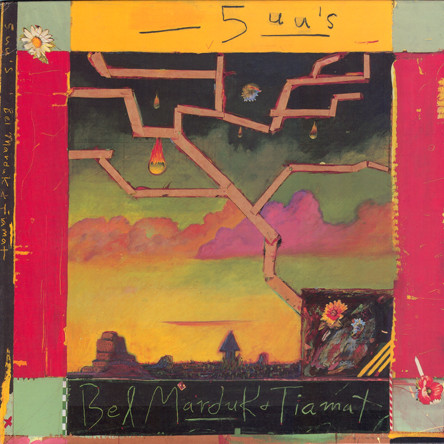

Would love to hear what are some of the strongest memories and ideas behind the making of ‘Bel Marduk & Tiamat’?

The first album, from 1984. Well, in retrospect, I had NO CLUE of what we were doing. I only felt a need to create something out of the mish-mash of ideas going through my head. There were no drugs involved other than lots of beer, but even that couldn’t help me make sense of it all. It’s the same to this day, forty years later, only now there’s enough experience to make it more convincing, and LOTS of friends have helped me along the way.

The first drum recording session for the album had all the makings of a disaster. I loaded my gear into the car and made my way through seventeen miles of L.A. traffic to the studio in Burbank. But stupidly, I left the bag with the cymbals in the alley behind the driveway. I arrived to set up the drums, but no cymbals. I figured I could either drive an additional three hours round-trip to get them—if they hadn’t already been stolen—or cancel the session.

But then I had an idea: In the studio yard was a barbecue set. What the hell, metal is metal, right? The stuff has been around since just beyond the Stone Age when prehistoric people melted it out of rocks. And I like to rock. With no offense intended to the Zildjian family, instead of cymbals, I used parts of the barbecue. The lid became the crash cymbal. The base—which one would normally fill with charcoal—was the ride cymbal. And the grill rack was used as a hi-hat. My dear friend Curt Wilson, engineer and singer, was in stitches having to record this. But it worked… because metal is metal.

Another fond memory of the first album is when I got The Residents to help me produce a vocal track over the phone. They’d done a wonderfully camp version of ‘All Around The Mulberry Bush’ on their ‘Diskomo’ EP, and I wanted that vocal sound. But Curt and I were obviously going about it wrong in the studio. So I had the information operator put me in touch with Ralph Records in San Francisco. The conversation was pretty much like this:

RING RING.

RESIDENT: Yes?

ME: Could I please speak to a Resident?

RESIDENT: (In the faux redneck accent) They’re not heeeere. They’ve gone bowling.

ME: But I recognize your voice and could really use your help. I’m in a studio in L.A., trying to get the ‘Mulberry Bush’ vocal sound, and I’m paying by the hour to fail miserably.

RESIDENT: Well, young man, if I’m not mistaken, the Residents recorded the vocals directly to their multi-track machine, took the signal out of the mixing board through a Leslie speaker at half rotation speed, re-mic’d it, and fed the signal through a harmonizer back onto the multi-track.

ME: Great. Could you please not hang up just yet?

Curt and I managed to do this, but it took some minutes. To my delight, the Resident patiently stayed on the line. He was on speakerphone, and we could hear all kinds of weird noises, metal things dropping on the floor, and grunts and squeals going on over there.

ME: Wow! I think we got it!

RESIDENT: Yes, that sounds very good over the phone. Now, young man, I must go pick up the Residents from the bowling alley.

ME: Are they good bowlers?

RESIDENT: All strikes and spares.

ME: How do they manage to bowl in the eyeballs and tuxedos?

RESIDENT: They leave the hats in the car.

That was the second-to-last track on the record, and a weird way to start winding it down.

I guess the album was privately released? How did Chris Cutler find out about it?

Yeah, I made my own label, urged on by my good friend, James Grigsby, who had already managed to do the same. He’d done the legwork, and both of us knew that no record label was going to sign us. When the song with the Bar-B-Que parts was finished, I gave some cassettes to friends, one of whom was a bail-bondsman, whose job one evening was to get a famous rock star out of jail. When doing the final paperwork in his car, he played that cassette. The famous rock star got unnerved and asked, “Is this going to take long? Because this is the worst shit I’ve ever heard!” When my pal related this to me, I realized that I could well be on the right track: That reaction reminded me of the first time I heard Henry Cow.

Anyway, yes, it was privately released. Back then, making a vinyl record was easy, if you knew what to do and where to go. James guided me through the steps over strong coffees. We used Frank Zappa’s mastering engineer (Jeff Sanders), a fly-by-night printing company, and a pressing plant that couldn’t care less if the music was avant-garde or for Korean porn.

I sent Chris Cutler the stuff and was surprised by his speedy response. He liked about half of it and was not at all keen on the rest. His corrective criticism was food for thought. And he promised that there was enough potential to consider releasing a second album on Recommended Records. That’s all I needed to hear. He wasn’t the famous rock star needing to be bailed out of jail.

“Gear might merely be whatever is on hand”

Tell us about all the gear you had back then?

I must say that I’m no gearhead, and I wouldn’t go to the NAMM show even if promised immortality. But I’ve had some lovely sets—my favorite was a Gretsch—and some total stinkers. They sound pretty much the same to me. What a lot of people don’t realize is that it’s the way drums are “struck” that makes a drummer’s sound. Everyone has their individual dynamic: velocity, stick angle, rim attack, stick release, tuning, and all that. And then, of course, there’s the phrasing. When Keith Moon played John Bonham’s drums, no one was fooled. I don’t usually travel with a set, so it’s been a matter of accepting the backline a venue has to offer. Sometimes it’s a Cadillac; other times it’s Rent-A-Wreck. And that variety makes me both challenged and, I hope, versatile.

Some years ago, I played at a jazz club in Zürich where the drum backline could damn near fit into a pillowcase; it was so small. That fact made me reimagine the drum parts I was playing, instantaneously. I was forced to come up with something different from what had been rehearsed, to fit the mood and the sound. I’m not so much an improviser as a guy who enjoys being forced out of his comfort zone.

But sometimes others must cover your back, and you need to find trust. I once played a gig in Nuremberg where the legs of the cymbal stands were missing. Two audience members volunteered to hold the stands upright. They sat by the drum set, cross-legged, poles in their chests, cigarette filters in their ears, through the entire show. I’ll never forget that tenacity. The point is to simply get it done.

And I remember the early days of the Estonian band, ZGA. Their music was thoroughly illegal back then. They had hardly any gear and couldn’t get microphones, so instead they recorded into speakers because both are basically a diaphragm and a voice coil. Again, the point is to simply get it done. Gear might merely be whatever is on hand, and it should mostly be a voice for one’s musical vision, in the hope of pleasing someone’s senses.

How did the collaboration with Motor Totemist Guild from Orange County, California, come about?

In 1984, I joined an organization called COMA (California Outside Music Association). The idea behind it was that like-minded, left-field bands could help each other get live gigs in and around Los Angeles. This was the era of post-punk, post-Progressive Rock, post-Folk music, and post-everything. New Wave had taken over, and it was something to be opposed, as much as the overt commercialism that fostered it. The ten bands involved with COMA had all been doing this for a while, and I came late to the game. The guy who had the most experience was James, whom I referenced earlier. He had his own band, Motor Totemist Guild, and I had 5uu’s. We quickly became pals, partners in musical crime, and decided to work on music together.

We did some strange gigs as Motor Totemist Guild. Like the time the city of Los Angeles gave us some bling to be “cultural ambassadors” to Laos. Our group was joined with a large handful of elderly Laotian and Cambodian refugee musicians and their traditional instruments. The idea was that we’d all play together as a sort of orchestra. But there was no chance of them learning James’ contemporary Western chamber rock, with so many shifting time signatures and key changes. And we couldn’t play their music convincingly because our European-based scales couldn’t match their Eastern, almost microtonal tunings. In the long run, we played Bach’s ‘Musette,’ as it’s quite well-known to both cultures. The show was cool, augmented by their traditional dancers and great curry, but quite bizarre. Afterwards, James said to me, “Can you imagine that? French classical music, written by a German, played on Indochinese instruments, in California, three hundred years too late?” I guess that’s the sort of diplomacy, improvisation, and compromise required of Ambassadors.

‘Elements’ was the result of this collaboration; tell us about it.

I remember writing the music while living in a wretched, weekly-paid, vagabond motel in downtown Torrance. It was called Park Hotel, so rich tourists would book it, thinking it was an exclusive joint. We’d laugh in glee from the smoking balcony as limousines pulled up, stopped for a moment, and then drove off. My room was filthy and tiny, with one window. My view was a brick wall, three feet away. When I had composer’s block, I’d watch the snails crawl along the wall until an idea would come about. Someone had loaned me a Clavinet, so, with the exception of one song, the entire album was composed on it. The lone song was written on an autoharp later.

For the collaboration, Motor Totemist Guild and 5uu’s were using the same studio and engineer, Curt Wilson, who also sang for both bands. At some point in the recording, Chaka Khan got us bumped from our studio time, so we used Chicago Transit Authority’s facility in Malibu. They were really cool guys. When on tour, they’d rent out their expensive studio for dirt cheap to bands they felt deserved encouragement, and we needed it. At this point, there were twelve of us, all with different personalities and musical leanings. But it sounded good, and we worked OK together, perhaps because everyone was recording their parts at different intervals. It was impossible, schedule-wise, to all be in one place at any one time. To this day, one member of each band has never met.

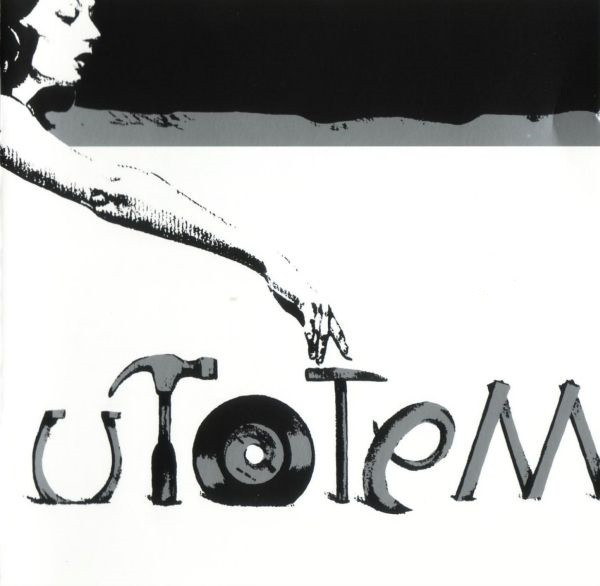

I guess that led to U Totem?

Right. One day we got a call from the Frankfurt Artrock Festival, asking us to replace Diamanda Galas on the bill, as she had canceled. The budget would only allow for four of us, but there were twelve, so we needed to truncate. Sanjay Kumar and Emily Hay were chosen to join James and me, both by means of necessity and function. Some of the others were no doubt hurt by this, but we knew what had to be done. It wasn’t until we returned from Europe that we decided to continue as five, by adding Eric Johnson on bassoon, becoming U Totem. Really, the last thing I thought we needed was a bassoon player, but I couldn’t have been more wrong. That instrument, more than the others, defined the sound and frequencies of the band. We played two tours of Europe and a ton of gigs in our native California. At one show, in San Francisco, I met up with an old friend whom I hadn’t seen in years. He’d become a brain surgeon in the interim. Not sure if he was pulling my leg, but he claimed to listen to our music when performing operations. The Residents, too. Dear lord, the poor nurses!

At the next show, the drums and bass amp didn’t arrive, so Sanjay and Emily played the gig as a duo (piano and flute). Some time later, I realized that we’d missed a great opportunity to entertain. I could have played crazy air drums, and James air bass, and really hammed it up for the audience. But back then, we were so well-rehearsed, and so focused on the notes, that we’d not taken the audience’s inklings into account. We went on to make two studio albums, both of which showed some whimsy. We lightened up after a while, becoming more entertaining.

How do you see those two U Totem albums for Cuneiform Records?

I hear them as two very different beasts. The first, eponymous album was truly a band effort, with staggered pieces by James and myself. We rehearsed it an awful lot; four or five nights a week after our day-jobs, and in one long day and night session every weekend. The music required it because it was pretty nuts. On one of my tunes, ‘Both Your Houses,’ I played a wooden temple block pattern. In the rests between the percussion lines, James wrote a melody, sort of; the flute is playing Sabbath’s ‘Iron Man,’ and the bassoon, Cream’s, ‘Politician’. The notes go by so fast that nobody in thirty-five years has recognized them, so I suppose I can spill the beans here.

We’d spend hours on one section to get it perfect, only to have it become somewhat Greek the next day. So, the process of the first album was arduous, to the point where all five of us became obsessed with its method and completion. Obsessed to the point that our significant others at the time threatened to leave us. I don’t recall that we felt especially intimidated, and we all ended up marrying others anyway.

By comparison, the second album, ‘Strange Attractors,’ was all James. He had written a story libretto, and all of the music for it. I had also written a bunch of stuff, but decided to defer to his concept. We initially thought to make a double album, one disc of his music and the other mine. But this would have taken too much time, energy, and money. It would have also created a situation where one might not necessarily compliment the other. I opted to save my stuff for later. Of the two studio albums, I prefer ‘Strange Attractors’. The story is concrete and focused because it’s one composer’s vision and holds together very well. Also, we learned many of our parts individually and often recorded them separately in a far less obsessive manner than the first album. The music is equally ridiculous but was easier to come by.

For how long did you know Bob Drake from Thinking Plague, and how did that lead to the reformation of 5uu’s?

We’ve known one another for thirty-five years or so. He moved from Denver to Los Angeles to seek gainful employment as a recording engineer. I didn’t think he stood a chance because there are only a certain number of credible studios, and thousands of folks looking to man them. Astoundingly, Bob got a gig on his second day of job hunting at one of the most influential studios in North Hollywood. Over the next few years, he recorded and produced some of the biggest-selling Rap and Hip-Hop hits of the late ’80s and early ’90s. He enlisted me to play drums for Thinking Plague, so we were traveling back and forth to Denver for rehearsals. It just seemed natural that he should join Sanjay and me to start up 5uu’s again in L.A. There was a studio to work at and a chance to make the music I’d originally come up with for the second U Totem.

‘Hunger’s Teeth,’ as well ‘Crisis in Clay’ were extraordinary albums. Hearing them today, what are some recollections from it?

‘Hunger’s Teeth’ was great fun. We needed a lead singer, so the three of us decided to “audition” for that role. The first to try it out in the studio was Sanjay. He was truly awful. Bob and I were biting our lips to keep from cracking up, as it was so funny. But I was next. I sang the part with my eyes closed, and with total conviction. It was my melody, I knew it well, and thought I could sort of carry a tune. When finished, I opened my eyes and peered through the glass into the control room, where the other two had been. But they were gone. WTF, I thought. When I entered the control room, I found them both rolling on the ground, laughing hysterically, holding their sides, with tears in their eyes. It would take years before I would ever sing again. Bob, by comparison, has a wonderful voice, so got the job. Susanne Lewis, then the singer for Thinking Plague, was in town, and graciously sang a couple of the songs.

Tell us what led you to the formation of Studio Midi-Pyrenees and the renovation of an old farm house in France.

The origins you should ask of Bob. I do recall that I arrived first for our endeavor, which had already been on the table for a while. The farm that eventually became the studio and residences had been mostly abandoned for some years and needed to be cleaned and fixed up a bit before anything could happen. One of the principals, Maggie T., and I drove down from Rotterdam with a bunch of necessities: stoves, furnishings, and the lime green Recommended Records Volkswagen delivery van, lovingly referred to as “Jump Sturdy.” I spent months alone there, cleaning, mowing grass, scything brambles, painting walls, burning what couldn’t be recycled, and writing songs. Since it had been empty for quite some time, forest animals had been using it for shelter. I evicted lots of mice, but they seemed to always make their way back. And the Glis Glis. And the snakes and rats. One day, when coming around a corner, I bumped into a baby pig and had to jump on a bicycle to escape its angry mother. Thankfully, the road was downhill. It was pretty wild in the beginning, but over the years has become fairly luxurious in an artsy, countryside way.

‘Crisis in Clay’ was recorded there, right?

Yes. I’d written a bunch of songs, and Bob and I set out to record them straight away. Later, the studio would become well-equipped, but back then, it was fairly bare bones; a mixing board that, if memory serves, had been constructed by Maggie, from Russian parts and electronics. And two Adat machines and a few microphones, but hardly any effects. The farm has quite a lot of different-sized rooms and spaces, so Bob utilized them for specific atmospheres. Everything from an absolutely thunderous drum sound in a large cement barn to a very tight guitar slap-back in a sheep dip. We used every space we could think of. I have a fleeting memory that we ran mic lines into the yard, out of a window, and recorded something in the van, maybe vocals (?) with the motor running, but I can’t recall if we ended up using it.

The entire place—and it’s fairly huge—became the studio environment. And there were lots of things to make noise with. I believe we beat both Faust and Einstürzende Neubauten to a cement mixer solo, but please don’t quote me. There was a discarded telephone pole in the courtyard that had been partially chain-sawed up for firewood during the winter. Come Summer, it became a battering ram. Freakin’ loud! We recorded percussion on a big oil drum in the little kitchen, and had mic cables strewn about everywhere, in most of the rooms, and out through the walls. Damn, it was fun. Sanjay came to do the keyboard tracks and played most on a mini controller—the antithesis of big—but the sounds were in the Goldilocks zone.

Before the recordings were complete, we set off on two tours of Europe, which seemed a friendlier environment for our wares than the States. The first in Western Europe, and the second in the Eastern parts. Sanjay couldn’t make these, so Scott Brazieal stood in. We played all sorts of venues. Everything from an indoor pistol-firing range to a converted firehouse squat, from a puppet theatre to nice auditoriums. We couldn’t be so selective on some nights, and took whatever we could get. Especially in the East, where it was still a bit chaotic, as the wall had fairly recently been torn down. We learned a lot there, not the least of which was that we couldn’t act like divas, which we weren’t wont to do anyway.

What made you return to the US and how did the lineup change of 5uu’s?

The times, they were a-changin’. After three years, I owed everyone money. Besides Bob and Maggie, there were also the touring musicians, my good friends Mike Johnson, Scott Brazieal, and Mark Smoot. They had paid their own way from America and worked like dogs, surviving on the bare minimum while showing a ton of respect throughout it all. I couldn’t, in good conscience, leave the debts unpaid. Some other good friends in Denver had opened a retail store and offered me a job, so off I went. But it would take a while.

I financed my trip back by playing a tour with the Belgian band, Present. I brought very little with me, but the most important item was a blue suitcase stuffed with all of my new song demos, lyrics, notes, and other bits. We were traveling for six weeks through Europe, and the band was getting pretty great. All the while, we had a roadie who knew not to remove this suitcase from the van for any reason.

Towards the end of the tour, in Austria, we played with the Welsh band, Man. Their entourage could out-smoke God himself. Our hotel was adjacent to the venue, and when I woke up in the morning, I was aghast. I looked out the window to see our tour van in the parking lot with its back doors completely open, the roadie passed out inside, my drums disassembled, and all the amps scattered outside the van, in the pouring rain.

We managed to salvage most things, though the drums were already starting to warp. They made it through the rest of the tour, but in the chaos that morning, the blue suitcase got lost, and I feared all of my new songs were lost with it. The last show of the tour was in Munich, and during the soundcheck, one of Man’s retinue, a very kind and determined lady named Sabine, walked in with the suitcase. She had driven many hundreds of kilometers all over Germany for days to track it down. Such kindness, and a marvelous example of human spirit and care.

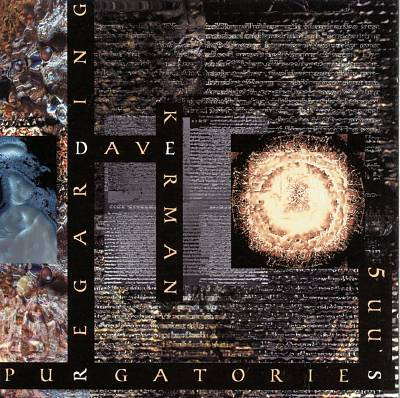

And this led to ‘Regarding Purgatories,’ released in 2000?

Yes, because she’d located the suitcase, all my demos were returned to me, allowing me to start on the album in Denver. We began recording, just myself and Mike Johnson of Thinking Plague, but then Keith Macksoud, bassist for Present, joined in. An old uu, Chuck Turner, was there as well. I had to re-learn a lot of keyboard parts and played them on the array of digital synths in the studio. When Sanjay heard what was going on, he mentioned that the keyboard sounds “fairly sucked” and convinced me to replace most of them with piano and organ. It was a smart move. Digital keyboard technology changes all the time as new products are released, and sounds can become quickly dated. The sound of a piano, however, seems almost timeless. Deborah Perry, also from Thinking Plague, flew in for the vocal sessions.

We did more overdubs and mixed with another Thinking Plague member, Mark McCoin, at his Brave New Audio Studio. Mark was game to let me do some weird stuff there. In the basement was a piano that had been totally destroyed in some art action. The parts were askew on the floor, so I played a solo on them. I also did a vocal track with my head and an SM58 microphone in the kitchen oven. The sound was really metallic and strange. I like strange. All the shenanigans came about because one determined woman in Germany had gone the extra mile.

What about ‘Abandonship’?

That was the next album, made in Israel. I had relocated to Tel Aviv, spurred on by my dear friend, Udi. He offered me a small apartment for free, provided I did some work on it. It was a block from the port, and because it had been empty for a while, we had to exterminate some giant-sized roaches and hundreds of red worms coming from the faucets and bathtub (at the time, Israel was having its reservoir water tanked in from Türkiye). It was like a Stephen King movie, only funny.

And then I found myself totally out of my element. I went to language school every morning, in an attempt to fit in. Sadly, I got most things wrong; the words for “glasses” and “pants” are similar in Hebrew. So, after forgetting my sunglasses at the checkout counter in a hardware store, I returned, proudly and assertively asking, in truly poor Hebrew, “Excuse me, I’m quite sure I left my damned pants right here. Have you found them?” Everyone in line burst out laughing. I also managed to accidentally brush my teeth with mosquito cream and was almost arrested for stealing a bottle of mouthwash to unlock my sunken cheeks from my teeth.

But before long, some friends had loaned me equipment: keyboards, guitars, a bass, and a 4-track tape deck. I set about writing the album, ‘Abandonship’. I wrote and wrote and wrote, about sixteen hours a day, for a month. I recorded every idea that came up and had a corresponding index card for each, taped to the wall, denoting the key and approximate beats per minute. From there, it was like concocting an ugly jigsaw puzzle to fit everything together into song form. But the pieces were soft like clay, so I could cheat and smoosh them together into a Frankenstein thingy. I played most of the instruments myself, but some friends added their talents here and there.

Would you like to discuss ‘The Quiet In Your Bones’?

After returning to the USA, I spent years as the North American distributor for ReR / Recommended Records. We had a fairly posh office, all the national accounts, and a lot of determination. After fourteen years, the advent of streaming made sales next to impossible. No matter how much I downsized, I couldn’t keep the company afloat. We bowed out of business as gracefully as possible, and I moved to Switzerland.

This left me free to write music again, which I hadn’t done in a long while. We put a new 5uu’s together, in theory, to play the Rock In Opposition Festival in France, do a tour afterward, and make an album, ‘The Quiet In Your Bones’. Sadly, the yearly festival couldn’t survive Corona, and all came to a grinding halt, leaving me with half a demo I’d made for the others to learn the tunes from. I decided to finish it up, pretty much alone, though the others are heard sparsely, here and there.

My father-in-law gave me a harmonium that was built in 1846, in Stuttgart, and has been kept in immaculate condition all these decades. Germany’s tuning prior to the Treaty of Versailles was not A440, but Diapason 435, and since this harmonium is on most of the tracks, everything sounds a bit creepy. I like creepy.

I did lots of weird experiments with the sound. I recorded tracks from the point of view of a witch being drowned off of our Middle Bridge here in Basel, by submerging a microphone in a funnel into a tub of water. The mic stayed dry due to trapped air. I played my cheap-o Strat copy through the speakers of children’s toys. I recorded the quietest of sounds and then boosted them up with limiters and overdrive to become monstrous. I had some time set aside and was out to have fun. Anyway, it’s my latest album, and it came out about a year or so ago. Again, on Cuneiform Records.

You have been active with several other bands, including Present, Thinking Plague, Aranis, and Stepmother. I would love it if you could discuss those collaborations.

In a nutshell, I’ve played in bands from several countries. This gave me the opportunity to live in France, Slovenia, Italy, Israel, and now in Switzerland. What I find great is just how much language, location, and culture tend to influence the musical tendencies of bands, almost to a stereotypical degree. For instance, Stepmother’s music “sounds” like Holland to me – colorful, busy, and crazy, but also assuaging and with an economy of means. Present and Aranis’ music “sounds” like Belgium to my ears – dark, cold, secretive, and foreboding, while somehow extending much human warmth and a kindred sense of care. Thinking Plague “sounds” like America to me – young, determined, and aggressive, but with a boldness beyond its years. Currently, Les Reines Prochaines “sounds” like Switzerland to me – wacky, multi-faceted, isolated, and roughly hewn, offset by lenience, independence, and longevity. I’m certain that these correlations are more than chance observations on my part, or the culmination of my experiences in these places. Rather, these are the ways by which culture can become ingrained in a group’s creative mindset, musical tendencies, and poetic language.

Looking back, what was the highlight of your time in the band? Which songs are you most proud of? Where and when was your most memorable gig?

The highlight of the band was the 1994/1995 European touring outfit. While I still enjoy recording a lot, there is nothing quite like making an audience happy or contemplative and feeding off of the energy. That particular lineup did wonders in that regard. A great recording might sound wonderfully the same most every time, whereas no two concerts will ever be the same experience.

I can’t pick out any tune to be proud of, as they are all like my babies. Truly, while being a decent drummer, playing and writing for the rest of the instruments is a difficult process. Basically, I can hear something in my head: a bass line, a melody, an arpeggio, whatever, but I usually struggle for a while to be able to play it and relate it to other musicians to perform. Since I’ve spent so much time on any one song, no matter its length or complexity, it seems hard for me to compartmentalize any one thing. I’ve never had children, so the songs became like my kids. I could never choose.

The most memorable gig was actually a soundcheck, in Würzburg, with the band Present. We were the second act, and were promised a one-hour soundcheck without an audience, so the audience had to go outside and wait. As soon as we started to work, there was a torrential downpour, and hundreds of people were getting terribly drenched. We agreed to let them in. They gratefully shook off, took their seats, beers in hand, and just stared at us. Our sound man, Udi, was still tuning the room, and the house lights were on.

We couldn’t do our normal soundcheck like this, so we turned it into a comedy act. The band had been together for quite a while and knew how to clown around with each other, but here came the chance to clown with others. I ran up and down the aisles and rows of people, frantically playing the drum solo of ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida’ on their heads with straws. Meanwhile, the cellist stood up and loudly conducted the audience to have a singalong to ‘Carmen’. “La donna è mobile, qual piuma al vento, muta d’accento…” and then murmurs and guffaws all around because no one knew the rest.

Others in the band were on stage, playing our ridiculous beer-drinking game, “Cat’s Dick.” If one of us burped, the last person to touch his outstretched thumb to his forehead got flicked on the crotch. Most of the audience had been drinking beer, so the belching game moved on to them, en masse. It was a hoot. Finally, it was time to play together, but the festive mood was infectious. Instead of sound-checking in our normal, dour, dark, gloomy avant-prog style, we played each section differently: Country Western, Polka, Slapstick, R & B. Man, everyone was laughing and having fun. And this was a band that wasn’t supposed to exude fun. We’d been together for years and only improvised once in Gdansk, and that was a vamp on a Universe Zero lick. Here, we could pull out the stops. Rock ‘n’ Roll!

What else currently occupies your life?

I’ve been living in Basel, Switzerland, for twelve years. I’m as spoiled here, by family and friends, as I was back in childhood, in Torrance, California. A wealth of opportunity simply fell into my lap. Still in and out of live bands, but recording somewhat less. I’ve done theatre work here as well, with the Swiss Art Rock Troupe, Les Reines Prochaines and Friends. We had a great engagement at Theatre Basel—sixteen shows, though two were canceled by the second Covid lockdown. I also work with a smaller, independent theatre, Vorstadt. More and more, I can foresee myself acting as opposed to playing music, though it might be a little late in the game for that, and I’m not too terribly handsome in my golden years.

Also, I’m working on a new album, a sort of follow-up to the last one from 2022. Working for theatre has greatly influenced the way I currently compose. Instead of sitting down with some instrument and coming up with ideas, I’m inclined to compose “scenes” in my mind, which I then set to music. I imagine actors on the big stage, the sets, the props, the lights, and the enormity of the space, from the audience’s view, which gives me a different perspective from that of a keyboard or fretboard, and that’s where the process for each song now begins. Although the outcome may not sound so much different, the impetus surely is.

Let’s end this interview with some of your favourite albums. Have you found something new lately that you would like to recommend to our readers?

Well, nobody shares my taste in anything. And I don’t really have time to obsess on new music like when I was younger. If I may, I’ll instead list some of my favourite Art Rock records, in case someone has missed a couple and would care to investigate:

‘Captain Beefheart: Trout Mask Replica’

Nico: ‘The Marble Index’

This Heat: ‘This Heat’

L. Voag: ‘The Way Out’

Art Bears: ‘Winter Songs’

Mnemonists: ‘Horde’

Faust: ‘Faust’

The Residents: ‘Third Reich & Roll’

Robert Iolini: ‘Songs from Hurt’

ZNR: ‘Barricade 3’

Ilitch: ’10 Suicides’

Jon Rose: ‘Perks’

Negativland: ‘Points’

David Bowie: ‘Outside’

The Red Krayola: ‘Soldier Talk’

Michael Vogt: ‘Argonautika’

Lemon Kittens: ‘We Buy a Hammer for Daddy’

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Thank YOU for the opportunity to blather! I’ll then take the time and space for some shameless self-promotion:

Cuneiform Records recently issued a live 5uu’s concert from Würzburg, Germany. It can be found on Bandcamp.

And the latest studio album is here.

Have a lovely day!!

Klemen Breznikar

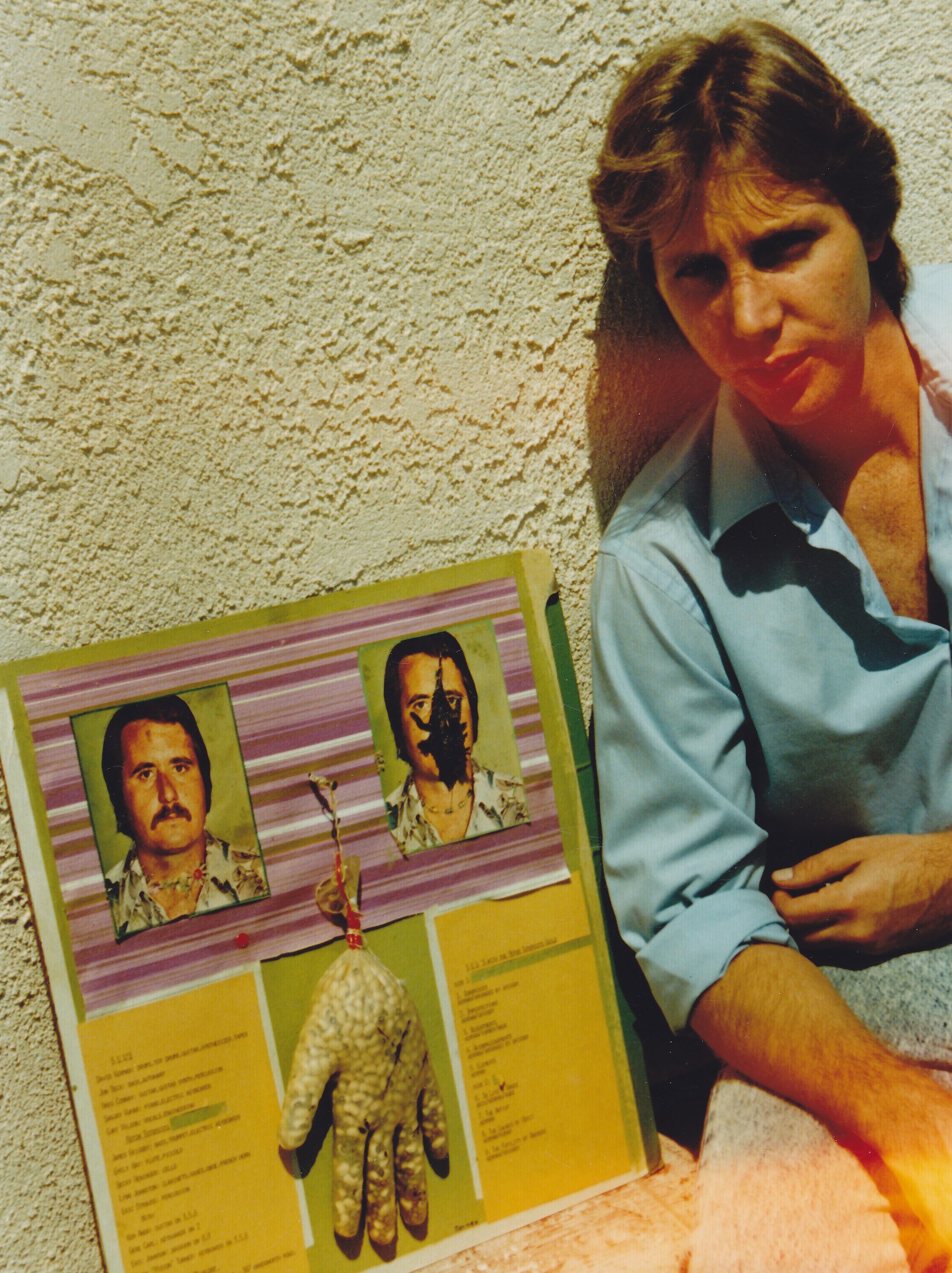

Headline photo: 5uu’s | Sanjay Kumar, Bob Drake, David Kerman

David Kerman Facebook / Bandcamp

Cuneiform Record Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / Twitter / Bandcamp / YouTube

We should work together on some new music…

Excellent interview!

excellent. and and and, ciao Dave!