Big Boy Pete | Interview | “We were about one week into the Beatles tour…”

Peter Miller, also known as Big Boy Pete, has had a career spanning several decades, involved in a variety of projects, including touring alongside the Beatles and Rolling Stones. He is most well-known to many of our readers for his 1968 single, ‘Cold Turkey.’

Originally from Norwich, England, he made San Francisco his home in 1972, where he has resided ever since. Emerging from the vibrant 1960s English pop music scene, he began his career with the Offbeats, a rock & roll band that released an EP in 1958, before joining Peter Jay & the Jaywalkers in 1961. He toured extensively alongside legendary acts like The Beatles and The Rolling Stones during the British Invasion. David Wells, founder of the British archival Tenth Planet record label, has curated four albums featuring Miller’s 1960s music. These albums have been distributed through Dionysus Records and Gear Fab Records in the U.S., with recent releases also available from Raucous Records and Double Crown Records. His recording studio in San Francisco played a pivotal role in documenting the early punk rock scene. In addition to his musical career, Miller is the founder and CEO of the Audio Institute of America, an online school for recording engineers that has trained thousands of students from more than 130 countries.

“We were about one week into the Beatles tour…”

Would you like to tell us where you were born and what you could say about your upbringing? Do you recall a certain profound moment when you knew you wanted to become a musician for the rest of your life? What did your parents do, and when did you first get interested in music?

Peter Miller: Back in 1957, after I caught sight of Chuck Berry duck-walking across the screen in the movie classic “Rock Rock Rock,” I dreamed of the mythical ‘Johnny B. Goode.’ I sold my Hornby Dublo electric train set for five pounds to buy a secondhand guitar. It had been only two hours since I left Chuck Berry at the Regent Theatre on Prince of Wales Road, Norwich. “I saw him duckwalk across the stage, and it was all over. Sorry, Mum, sorry, Dad, I’m not going to be that doctor you wanted. Back then, you were a weirdo if you were in a band; now, you’re weird if you’re not.”

What are some of the very first high school bands you were part of?

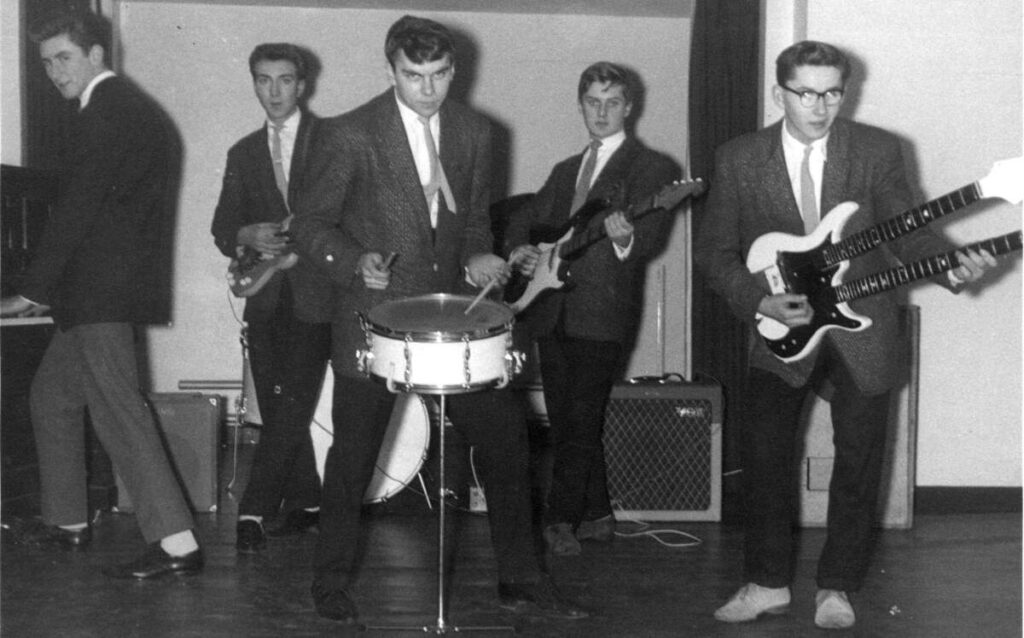

I went to an all-boys public school – which, in fact, means a private school in England – and it was very academic, very anti-rock ‘n’ roll. However, there were a couple of kids in the class who grooved, listened to records. Dave Wilson was in my class; he had crafted a homemade electric bass guitar, and we started playing Elvis songs together. We found a drummer, then a rhythm guitar player, and a singer – and then we got a gig! Thus, the Offbeats were born. We rehearsed at our local youth club and gigged at local teen dance halls. The affection we maintained for our idols was reflected in the songs we performed: Jerry Lee, Chuck, Lonnie, Gene, Eddie, Buddy, Fats, and, of course, Elvis. The members of The Offbeats were Luke Watson on drums, David Wilson on bass (later replaced by Mike Parish), Mike Lorenz on rhythm guitar, Tony Woods on vocals (later replaced by Andy Fields, who also played piano), and myself on lead guitar. Incidentally, I reunited with the Offbeats in 2012 and recorded an album of original skiffle songs with them.

I learned guitar by listening to contemporaries such as Hank Marvin, Vic Flick, and Big Jim Sullivan. But it was the Americans – Chuck Berry, Scotty Moore, James Burton, Johnny Meeks, and Chet Atkins – who were my main mentors. I wore out the records learning their guitar solos note by note.

In 1956, the only way to hear the latest and greatest was fading in and out from Radio Luxembourg (208 on the medium dial). Most families had only one wireless set, usually in the parlor. The good rock shows aired later in the evening when most of us schoolboys had to be in bed, so we did it under the covers with crystal sets and earphones. The components for my set cost 16 shillings and sixpence. The following year, another medium emerged. Every Saturday evening, every kid would religiously watch the “Six-Five Special” on BBC TV – the only visual clues as to how the big boys did it: Eddie Cochran, Gene Vincent, Billy Fury, Marty Wilde, Cliff Richard. Hooped skirts and pointed bras, ponytails and bobby socks bopping to the big bad beat. Why else would you play in a band?

The skiffle craze was still hot, and I bought every Lonnie Donegan record that was released. Lonnie always used great guitarists in his group. It wasn’t until many years later that I learned his producer, Joe Meek, had actually produced and engineered some of the best Lonnie Donegan records. It was not so much the song as the sound, the tones, the groove. Of course, I didn’t know what producers really did at the time, but later on, I realized they imprinted a certain identifiable sonic footprint. Joe’s use of extreme compression was his magic wand.

Here are a few snippets from my 1957 diary:

February 14th 1957. (Valentines Day) Went to the Norvic cinema (in Norwich) to see Rock Around the Clock for the second time.

February 28th. 1957 Bought Little Richard’s ‘Long Tall Sally’ 78 record.

March 3rd. 1957 Bought Guy Mitchell’s ‘Singing The Blues’ 78 record.

April 13th. 1957 Bought Fats Domino’s ‘Blueberry Hill’ 78 record.

April 17th. 1957 Bought Humphrey Lyttleton 78 record of ‘Bad Penny Blues’

For a 14 year old kid – an amazing proximity of starbursts occurred in the single month of May of 1957:

May 5th. Make a home-made guitar with a cigar box, broom handle and length of wire. Take it to a friend’s house and he also makes one. We have our very first jam session playing Lonnie Donegan skiffle songs.

May 10th. Go to see the Saints skiffle group rehearsing at our youth club. (Tony Sheridan was the guitar player)

May 12th. A lady comes to my house and buys my Hornby Dublo electric train set for twelve pounds.

May 14th. Place a classified ad in the local evening newspaper looking for a guitar.

May 15th. Go to the newspaper office. There is one reply.

May 16th. Go to the Regent cinema to see the film ‘Rock, Rock, Rock’ in which Chuck Berry does the duckwalk while singing ‘You Can’t Catch Me.’ After watching the movie three times, I go to buy the guitar. It cost five pounds. It was an acoustic Spanish instrument.

May 20th. Buy the Bill Haley 78 record ‘Goofin Around’ – an instrumental featuring Frank Beecher on guitar.

May 24th. Buy a Lonnie Donegan songbook of sheet music with guitar chords for 2 shillings and sixpence.

May 25th. Listen to rock and roll show (Smash Hits) on Radio Luxembourg.

May 29th. Buy the Bill Doggett instrumental ‘Honky Tonk’ (78 rpm) featuring the exemplary solo by guitarist Billy Butler. Notate the complete solo on sheet music.

June 2nd. A friend takes a picture of me with my new guitar in his garden.

June 11th. Buy a box of new (steel) record needles for my phonograph.

(Incidentally, I recently recorded ‘Goofin’ Around,’ ‘Honky Tonk’ and ‘Bad Penny Blues’ on the instrumental album ‘Bang It Again!’ (by Bonney & Buzz on Double Crown Records)

You may wonder how I recall such vivid details of my 70-year-old antics. Well, maybe surprisingly, from January 1st, 1949 (when I was just seven years old) until May 20th, 1962, I kept a complete day-to-day diary. How many rockers can tell you exactly what they did on every single day for over 13 years, amidst the most dramatic events and days of their musical life? I am still a meticulous saver of data in all formats.

Sunday, November 3rd, 1957. It was a rainy day. I stayed in bed late, playing my records, then listened to Family Favourites on the wireless at noon. I went riding on my track bike in the afternoon through Valley Drive on Mousehold Heath. Andrew Hawkins, one of my classmates (who happened to have taken all the Offbeats photographs), and my parents came to dinner in the evening. After dinner, Andrew and I went to my “laboratory” and mixed some chemicals, constructing a homemade bomb by packing gunpowder into the steel rod casing of an old phonograph pick-up arm that was no longer usable. (I was proficient at making a variety of different explosives, including dynamite and TNT. In fact, I had written a “how-to” booklet detailing methods to produce about thirty different explosives with a home chemistry set.) I had recently been given some ex-government military fuse wire by my cousin which had not been tested prior to that evening. We took our explosive outside the house and set it down on the patio, and I lit it with a match. The 12-inch length of fuse wire was so old and brittle that it burned the whole length in less than a second while I was still leaning over the device. It blew me almost into the next-door garden and also brought down the plaster ceiling in the room where our parents were watching television. They whisked me off to the hospital where I was stitched up. For the next week, I stayed in bed playing guitar and was shot full of penicillin every day to fight infection because the pain would not go away. This was way back when the doctor made his rounds every day, happily making house calls with a bag full of needles, pokers, stethoscopes, and medicines.

November 12th, 1957. Went to the hospital with Mum to have an X-ray and a small operation to remove the remaining shrapnel from my leg. On the way home, we stopped at Woods music shop, and I bought a new Rosetti guitar. It cost 23 pounds and two shillings. “Smashing model. It has a roller bridge.” I had earned most of the money from fruit picking during the previous summer holidays, and Mum threw in 4 pounds while Dad gave me 1 pound. This was part of my Christmas present.

I augmented my allowance during the eight-week-long school summer holidays by fruit-picking at farms a few miles outside of Norwich (a city of 150,000 people situated about 100 miles northeast of London). I would bike to the farms at 7:00 am to see if there was work. Wages began on July 7th for 8 full days of work: 3 pounds, six shillings, and twopence (picking blackberries, plums, and green beans). Eight days of picking in August (beans and potatoes) totaled 4 pounds, 18 shillings, and ninepence. The final total for the summer was 8 pounds, four shillings, and sixpence (about US $30).

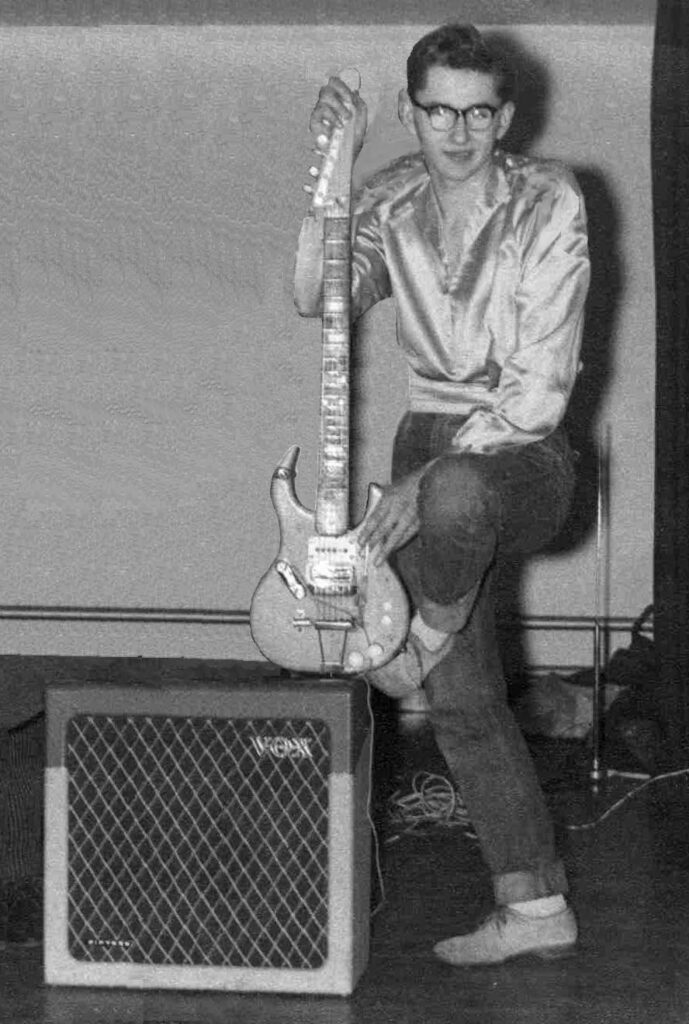

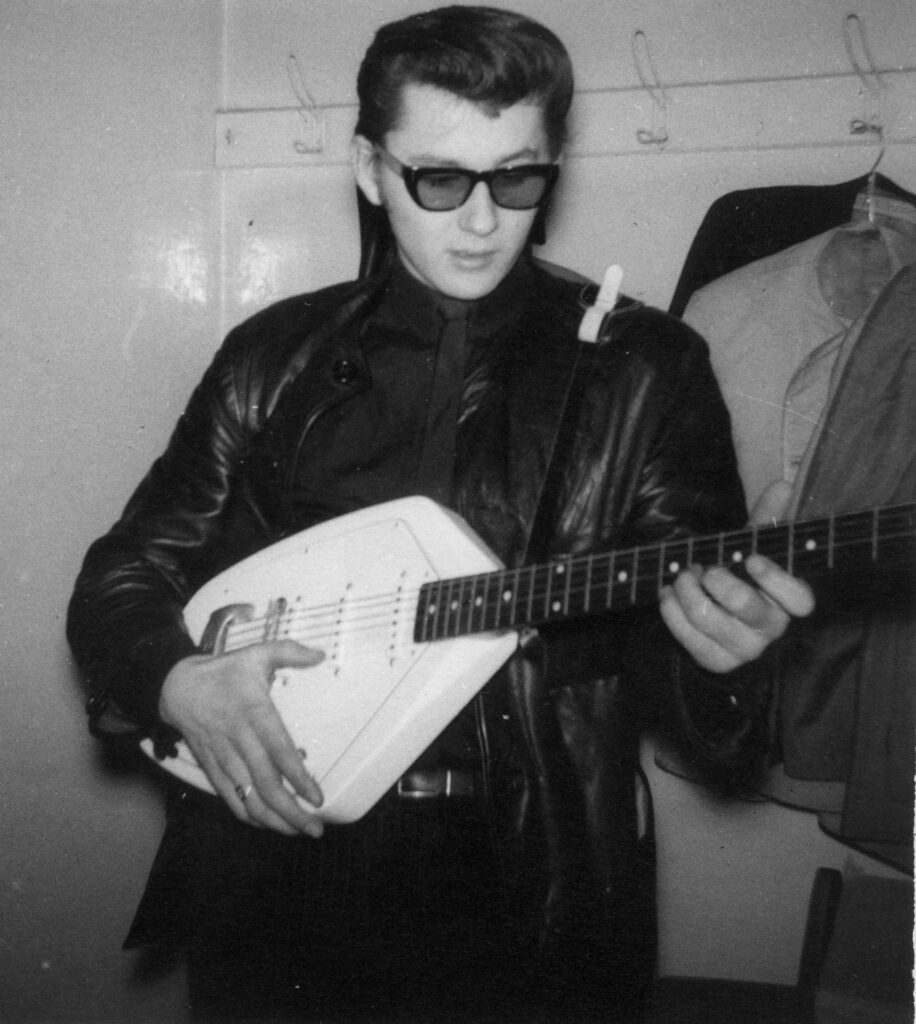

Up until then, I had only owned hollow-body guitars. I briefly saw a flash of a Fender Stratocaster on TV and, having no money other than my measly schoolboy allowance (about two shillings a week), decided to build a solid-body electric for myself. Armed with a handful of Dad’s primitive woodworking tools (and not even a vice), I buried myself in my Dad’s garden shed for about three months and finally emerged with a few cuts and bruises, proudly wielding “Warblerama” – a beautiful, barely playable turquoise-colored, tremolo-armed, DeArmond-equipped prize. It also sported a Rosetti pickup in the neck position. Both pickups had their own volume and tone controls and on/off switches. I had never heard an out-of-phase condition, so I guess I was just lucky when I soldered it all together – I had a soldering iron from my crystal-set making days. Having never seen a real Fender tremolo (or Bigsby), I was unaware that a spring was the secret. So I installed a metallic rest for the arm to sit in when not being used. Occasionally, I’d accidentally knock it off the rest and it would crash down onto the body of the guitar with an alarming, resounding boinging crash, detuning the strings about a tone, scaring the rest of the band and audience. The arm had a rather cool white plastic tip. I nicked it from a friend’s Austin Seven automobile; it was the turn indicator signal arm on the steering wheel. The neck was as long as a guitarlin neck – it must have had about 30 frets.

I also put together my own amplifier. My cousin made the electronics from a do-it-yourself kit, and I constructed the chipboard box, inserted a 12-inch Goodmans Audiom 60 speaker, and painted the whole thing sparkly black. It was quite a sight to behold: me bicycling three miles to rehearsals at the youth club, balancing the amp on my crossbar with the uncased guitar slung around my neck. No mean feat! Is there no length a boy will go to for rock and roll?

Another of my creations was a bass-reflex cabinet for my bass player. I acquired the exact dimensions for the cabinet and the correct position for the port from a popular science magazine. I “borrowed” the ten-inch speaker from my parents’ wireless console. I remember testing it by playing my 45 of Eddie Cochran’s ‘C’mon Everybody’ through it, which had a nice deep bass guitar intro.

I remember buying an “expensive” set of Fender guitar strings and holding onto them for months before installing them for a “really important gig!” (They didn’t sound any different from my normal Ivor Mairants set). Maybe it was the tortoiseshell plectrum!

Not a collector’s item by design, ‘Introducing the Offbeats’ – our 1959 six-song EP – survives as the Offbeats’ only recorded legacy on the Magnegraph label. It was a London company, and I just sent off the tape to them, and that was the end of it. I didn’t know anything about the record business in those days. I remember getting some copies, but I don’t recall how many were pressed. I don’t know anybody who has one. It was an instrumental EP, six songs, all originals. The Offbeats lasted a couple of years; I have a list of all the gigs that we ever did. We played about one a week from July 17, 1959, to March 16, 1961, then I joined another local band who seemed to be on the stairway to stardom.

How did you get the names “Big Boy Pete” and “Buzz”?

On January 26th, 1968, I made one last stab at commercial success by releasing my second solo record, ‘Cold Turkey.’ It was on the Camp label, a subsidiary of Polydor. The song was a kind of bluesy hard rock that bands like Blue Cheer would eventually popularize. At the time, however, no one wanted to play it. This record is now regarded as one of the most collectible 45s from that era. During the heyday of strange names, Polydor decided to release the record under the name Big Boy Pete without asking for my opinion or authorization. I was absolutely furious when I discovered my new name. When Polydor suggested a promotional tour, I flatly refused and told the executives to find another Big Boy Pete to do the dirty work. I agreed to continue writing, performing, and producing records under this name, but insisted someone else hit the highways. The record company reluctantly agreed and employed a touring stand-in. There exists a German video of this stand-in lip-syncing to the record on the famous Beat Club TV show. I never even met him, and I don’t know his name. I have a copy of that TV show. He looks cool in the video, playing a Stratocaster that isn’t plugged in, but he makes all the right moves.

I adopted the name Buzz when I was with the Jaywalkers because there were three Peters in the band. The name came from a popular recording at the time by an American named Buzz Clifford, and the song was called ‘Baby Sittin’ Boogie.’ Say no more!

Would you please tell us about Peter Jay & The Jaywalkers and the several singles? Did you do a lot of shows with the band?

InI was lured away from the Offbeats in 1961 by Peter Jay, who fronted the rival group The Jaywalkers, also from Norfolk. The Offbeats and the Jays had played a dance together on February 10, 1961. That was when Pete Jay decided that he was going to steal me from the Offbeats. He contacted me and said, “You must meet me in the Wimpy Bar.” (That was the musicians’ hangout in Norwich.) It was all kind of secret; we snuck into the back of the room because there were other musicians hanging around, and you were considered kind of unfaithful or disloyal if you started talking to another band. So my hangout went from the Norwich Wimpy bar to Soho’s coffee houses where I met my idol Hank B. Marvin one morning. We became acquainted early one morning over breakfast in the Golden Egg restaurant – opposite the 2 Is coffee bar in Old Compton Street.

The Jaywalkers were a popular sax-driven instrumental group that played the big theatres and were courting a record deal with Decca. We were basically copying American bands such as The Piltdown Men and Johnny & The Hurricanes, but we wanted to feature the guitar a lot more. Jay was particularly fond of my creative guitar techniques, which bolstered the Jaywalkers’ non-stop road show and helped boost us into the charts with the classic ‘Can Can 62.’ The Jaywalkers toured incessantly, playing a grueling road schedule of more than 300 gigs a year and backing up countless acts. I credit the heavy gigging with developing my chops and versatility. If there were nine acts on the bill, we would be backing up seven of them, so I was able to gain a lot of experience playing different musical styles.

With me on lead guitar, the Jaywalkers enjoyed immense popularity in Britain, releasing a dozen singles for Decca and Pye records between 1961 and 1966. Many of these tracks were produced and engineered by the legendary Joe Meek (Outlaws, Tornados, Honeycombs, Heinz, etc.) from Joe’s bedroom recording studio at 304 Holloway Road in London. It was from Joe that I learned many tricks of the trade as far as recording techniques are concerned, which is quite apparent in the sounds on the Big Boy Pete records. It was around this time that I turned down an offer from Clem Cattini to join the Tornados – just days before they recorded the worldwide smash ‘Telstar.’ No regrets!

Unfortunately, after a few months, the neck of my Warblerama guitar began to warp and the action became unplayably high, so I set about designing and building a replacement. But why not invent something different? Back to the woodshed with a few more ingenious ideas. I don’t think I had ever seen or known of the existence of a double-neck guitar at that time. Twelve weeks later, I emerged with Warblerama II, a lilac-colored wonderbeast sporting a six-string guitar neck and four-string bass neck. This time, I laid a steel rod surrounded by a bed of concrete inside each of the necks! The bloody thing weighed a ton and was totally top-heavy, but it sounded screamy and looked gorgeous. The Jaywalkers absolutely insisted I play it at The Windmill Theatre in Great Yarmouth when I joined them in the Spring of 1961.

I had been attending school during the day and taking my A-level exams, and after school, catching the train 20 miles to Yarmouth to do the show each night. Now the writing was on the wall. The applause pre-empted the academics. A career. It was an esteemed public school (a private school to you Americans), a highly conservative, ancient, boys-only school of unblemished repute. Lord Nelson had once been a pupil. I remember one lunchtime, I was severely reprimanded for playing my Jailhouse Rock 45 on the school phonograph. (“This machine is ONLY for classical music!”) Forty years later, the current headmaster visited San Francisco and asked if I would consider becoming the school’s US representative. How things change! It was nice taking the headmaster out to lunch and getting him tipsy on Thai Singha beer!

Most guitarists at that time used the Watkins Copycat for echo, but I had a red-colored Selmer Truvoice. Essentially the same thing but not quite the same sound. A razor blade and a reel of blank recording tape were mandatory road items at that time because the splice on the loop of tape would frequently come adrift due to the heat the unit built up. My tape-echo unit would last until 1962 when I upgraded to a Baby Binson which I bought second-hand from Jim Marshall’s shop on the Uxbridge Road, London. Hank B. Marvin used a Binson at this time. They sounded great but were prone to the rigors of the road. If the unit had been bumped around on the trip, the revolving metal magnetic disc would wow and flutter for a while before settling down to a uniform speed. I would warm it up for half an hour if possible before taking the stage.

At the end of that first wonderful summer season in Great Yarmouth with the Jaywalkers, where Tommy Steele and Frankie Howard were the stars of the show, my bright-red Hofner Verithin arrived, so I left the double-necked donkey in a dusty, darkened corner underneath the stage of the Windmill Theatre and happily ‘Verithinned’ my way onto my first Larry Parnes tour, backing the top pop stars of the day. I often wonder what happened to Warblerama II – I never did go back to look for it. Just look at the picture. Has anybody created a prettier-looking double-neck? Hofners had that distinctively indistinctive run-of-the-mill European pickup tone. Listen to Bert Weedon. Oh, and by the way, you won’t get famous if you play a Framus!

Then came the stage full of Voxes. The Jaywalkers had two bass players and two guitar players and also needed a PA for the dance-hall tours. The endorsement deal with Vox was very generous. They would give us what we asked for whenever we asked for it, and it arrived promptly. We didn’t take advantage, and luckily, this went on for a few years. Initially, the Vox equipment was thrust upon us without us being able to select individual instruments, but it was free so nobody complained. The AC30 amps were always great, but after a while, we became disheartened with the poor sound quality and virtual unplayability of some of the Phantom guitars. The twelve-string guitar was just dreadful. The four-string bass wasn’t at all bad, but the only instrument that really sounded great was the Phantom six-string bass. You can hear me soloing with this at the end of our ‘Poet and Peasant’ record and also playing the introduction to ‘You Girl’ on the Phantom 12-stringer.

Equipped with two bass players (a strategy that I employed in many of my later recordings), and a barrage of Vox equipment, the Jaywalkers made numerous TV appearances (Ready Steady Go, Thank Your Lucky Stars, Arthur Haynes Show, Cool Spot, etc.) and stole many a show from their headliners. Our stage show was probably the first really heavily choreographed rock group performance in history. It was not just our music; we were visually exciting, humorous, and colorful. In my five years with the group, the Jaywalkers toured and shared bills with the diverse likes of the Kinks, Animals, Dave Clark 5, Billy J. Kramer, Dusty Springfield, Cilla Black, Cream, Donovan, Freddy and the Dreamers, Billy Fury, Georgie Fame and the Blue Flames, The Tornados, The Moody Blues, Maryanne Faithful, Carl Denver Trio, Joe Brown, Eden Kane, Shane Fenton and the Fentones, Brian Poole & the Tremeloes, Marty Wilde, The Byrds, Gene Pitney, Freddie Cannon, Del Shannon, Gene Vincent, in addition to the Beatles and Rolling Stones tours. On the big Larry Parnes tours, which occurred twice a year, the Jaywalkers would play their own set and serve as backup band for the solo acts who didn’t have their own group.

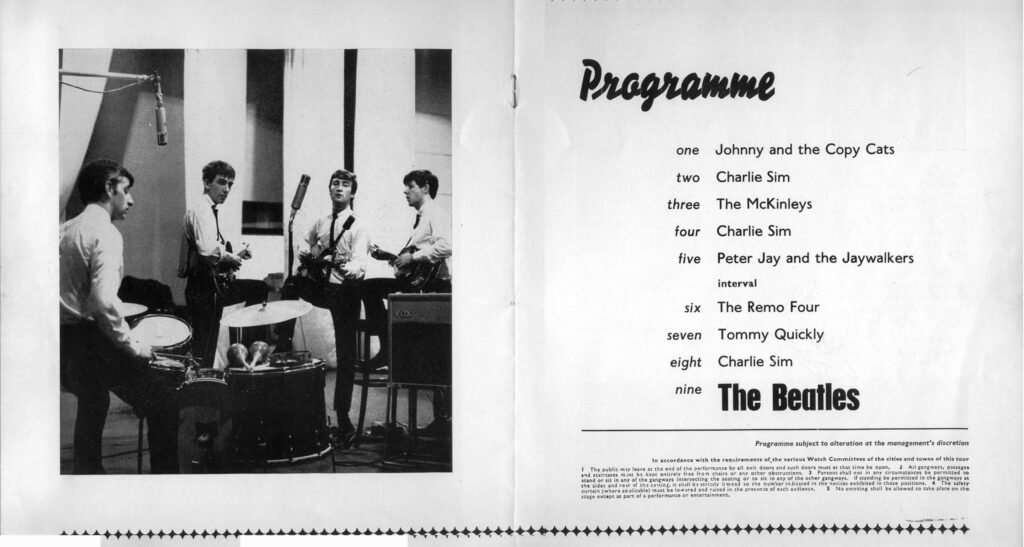

The popular success of ‘Can Can 62’ landed the Jaywalkers second billing to the Beatles on that legendary tour in the autumn of 1963, from whence the term Beatlemania was coined. Incidentally, our hit ‘Can Can 62’ was released the very same week as the Beatles’ first record ‘Love Me Do,’ and we both entered the charts at the same time. The Beatles were our pals. We had already hung out together a lot, even before we’d both gotten signed, they were just another band, like us. No big deal. When asked about those tempestuous times, another anecdote? Okay. I suppose no story is complete without a new Beatles’ anecdote.

(NB: For those of you who have travelled no further than your outhouse, Aer Lingus is the Irish airline.) I remember we were flying to Ireland. It was around noon on November 7th, 1963. We sat patiently on the runway at London airport awaiting take-off clearance. It was a regular commercial flight. We were about one week into the Beatles tour which was set to play the Ritz in Dublin that night and the Adelphi in Belfast the following night. I was sitting directly across the aisle from John and Paul. The captain came on the intercom, introduced the crew and then welcomed the passengers: “We are happy to have the pleasure of your company today on this flight to Ireland and we would like to give a special welcome to some famous lads. We have all the Beatles on board. Welcome to Aer Lingus!” John immediately jumped up out of his seat and yelled “Don’t ya mean cunnilingus?” Everybody on the plane burst into laughter!

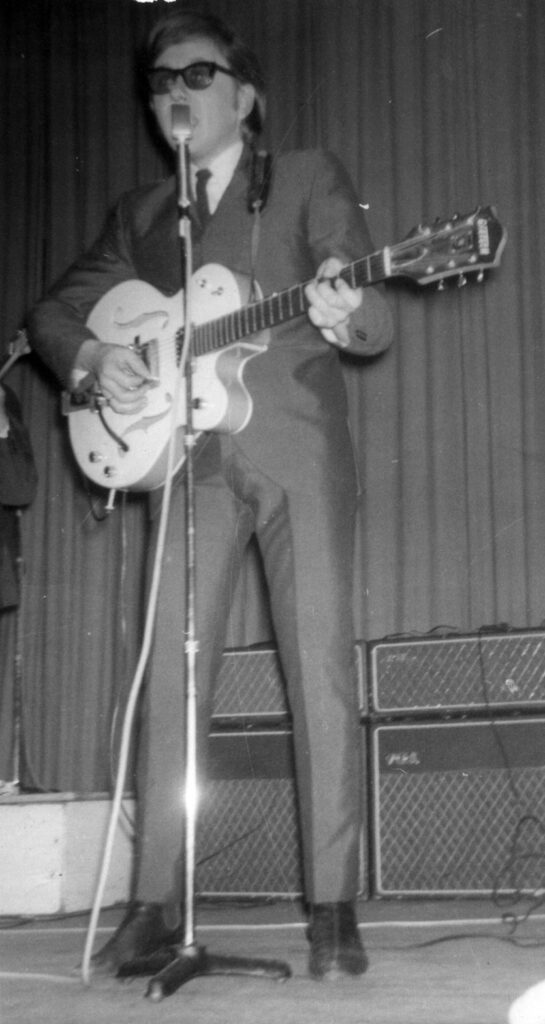

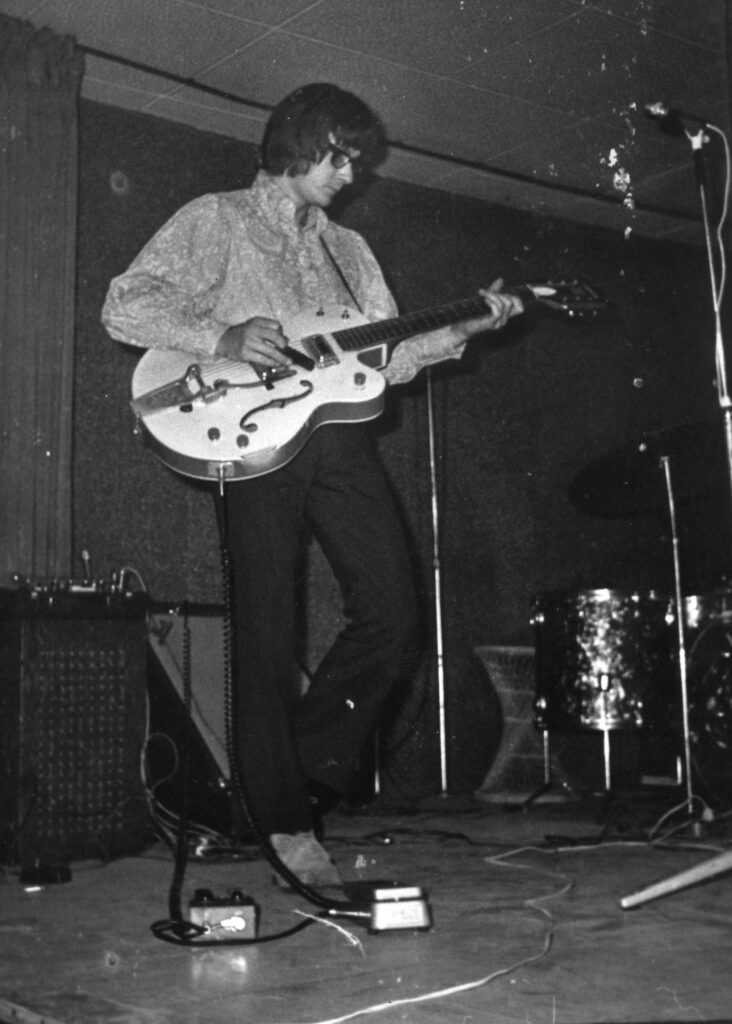

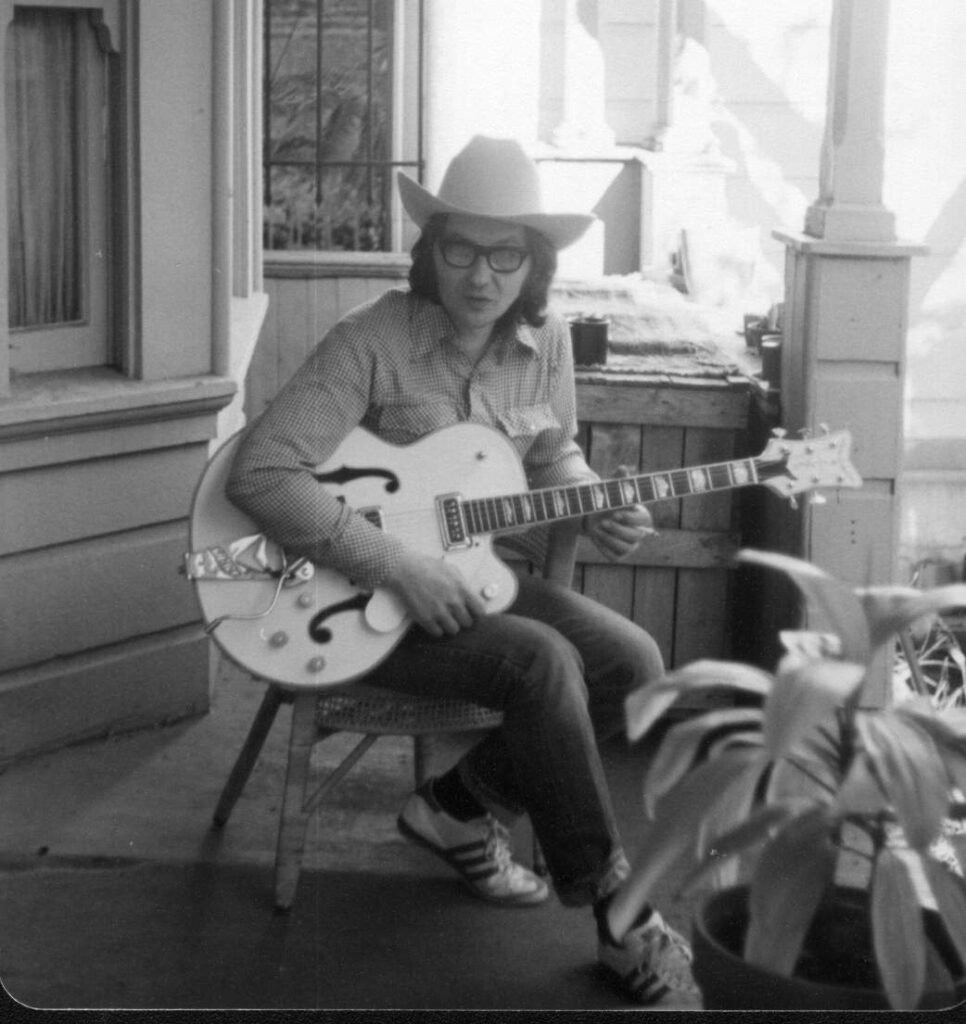

My debut on a major label as a guitar player, however, was not with the Jaywalkers – I played lead guitar for Marty Wilde on his minor hit single ‘Ever Since You Said Goodbye.’ The late Heinz (from The Tornadoes) was the bass player. It was recorded at IBC studios in Portland Place. Pete “Buzz” Miller (as I was known in those days) still plays the very same two-tone green 1961 Gretsch Anniversary guitar (Henry) that was featured as the lead instrument on all of the Jaywalkers records and later, on all the Big Boy Pete stuff. Like many of my contemporaries, I bought it on the never-never from Selmers on Charing Cross Road. Although somewhat faded, it still bears the shop name on the strap.

Incidentally, here’s a couple of pieces of trivia: Next door to Selmers were a couple of other notable shops. Jennings music store, run by Larry Macari, was the original outlet for Vox amplifiers and Vox guitars (with an old Italian accordion maker working in the basement). Next door to that was Annello and Davide, a tiny boot and shoemaking store which catered to the needs of Spanish flamenco dancers and ballet dancers. It was there that their handmade flamenco boots caught the eyes of all rockers, giving us an extra two inches in height. The boots later became known around the world as Beatle Boots. In 1972, the shop moved to a new location in the heart of London’s theatre district – Drury Lane.

“Every act on the tour used to wear suits that were made by the same tailor – Dougie Millings, who had a little shop down in Soho. Cliff Richard, Billy Fury, Marty Wilde, the Beatles, The Shadows, everybody wore his suits. They were about 30 quid each, fabulous hand-made suits in beautiful Italian silk, and Dougie would do one special thing just for us guitar players: Inside, under the right lapel at the top, I would put a tiny little pocket, a pick pocket, where we could store our plectrums. (Or is it plectra?). The Jaywalkers trademark was for us all to wear a different colored suit – yellow, red, green, orange, lilac, blue, and silver. Mine was yellow.”

“The annual calendar was a pretty hectic affair. A couple of months of dance hall gigs would begin in January followed by a spring tour, which would last a couple of months. This would be about sixty continuous one-night stands in theaters around Britain. Then the summer season would come along, taking 14 to 16 weeks in some beach resort like Great Yarmouth or Blackpool. After that, we’d go out on the autumn tour, another eight-weeker which would take us up to the end of November. Any odd days that we had off, we’d be in the recording studio or doing TV shows or photo shoots. The ballroom gigs would be just single nights in big dancehall chains such as Meccas, Locarnos, Hammersmith Palais etc. We liked the dancehall gigs because we got to play longer. On the tours, we’d only get to play about a 13-14 minute set per show – although we’d be backing most of the acts on the bill, so we’d be onstage most of the night. But on a ballroom gig, we would always be the main attraction and we’d get to play for 45 minutes. There would be one or two local bands opening for us. I met a lot of unknowns in those bands who later became big stars.

“Our first single was recorded at Decca studios in Broadhurst Gardens, Hampstead, in a large studio where they could record symphony orchestras. We did ‘Can Can 62’ in there, with Joe Meek producing. I didn’t get along with the Decca engineers because I couldn’t get the sounds I wanted. The white-coated boffins would not allow me to push the equipment beyond the limits into the distorting red zones, which was one of the secret ingredients to his unique sound. After that session, I decided I was going to record us in his own place from then on. Our second single was ‘Totem Pole.’ We were in Joe’s house in the morning, on Holloway Road, and I think I didn’t like the B-side that we’d prepared, and decided that I wanted to do something else. So I sent the boys down to the pub and asked them if they would stay and write the B-side with me. I was fiddling around with the guitar, coming up with lines, and a tune came together which we called ‘Jaywalker.’ It only took about 20 minutes or so. I remember at the time I was kind of surprised that Joe would let me get away with some of the lines I was doing – there were some kinda inside guitar things on there which a Decca producer would probably not have accepted. Then the boys returned and we recorded it. Joe was the English equivalent to Phil Spector. I really had an ear and a notion for the exact sound I wanted. I would watch, pick up stuff, and hang around with him after I was done recording us if I had another session booked. I became somewhat secretive later on when I thought people were listening through the walls and stealing his ideas.

“Our next single was ‘If You Love Me,’ an old Edith Piaf song with a nice melody. That was produced by Ivor Raymonde back at Decca number two studio, because there were strings and French horns and things, and Joe didn’t like to deal with that kind of stuff. I guess they probably wouldn’t all fit in his house! I remember we played ‘If You Love Me’ live on the Arthur Haynes TV Show. That was kinda scary because on almost all TV shows you would mime to the record. Furthermore, our management insisted that we used the Vox Phantom guitars that we were endorsing at that time, which although they looked cool, were never very playable and sounded like shit. (We never ever used them on our recordings.)

“We just weren’t happy with the way Decca was marketing us, and they didn’t want to release our records in America, and we wanted them out over there. So we changed labels and went to Pye (Piccadilly) records working under the production of John Schroeder with Eddie Kramer as engineer. Around that time, we happened to do a couple of dozen dates with the Rolling Stones. By that time, bands like the Stones and Kinks were getting popular. We decided we needed a new image, because although we had a massive fan club (about 10,000), we weren’t getting our records into the charts anymore.”

“So first off, we let our hair get a bit longer. Then we dumped the Beatle Boots for Nazi-looking knee-high boots. Got rid of the fancy suits, donned American style casual clothes and pretended to be cool. It was basically a conscious decision, we were changing horses midstream. I remember the Pretty Things opening for us in Glasgow, Scotland, and we were amazed. It was like looking at a Hammer movie, a Fellini movie or something! They were doing raunchy R&B, and although the music was great, their appearance was something awful. British bands up to that point, including The Beatles, were very clean-cut and professional, no fuckin’ around. The Pretty Things had a whole different attitude like we’d ever seen, and it blew us all away. Then we did a gig at Slough Adelphi with The Byrds, and their completely unprofessional, unpolished stage performance kinda sealed it. It was scruff-out time. I’m sure Dougie Millings, the tailor, was less than pleased with this wardrobe change.

“Talking about endorsement deals, George Harrison also had one with Gretsch. I remember midway through the Beatles tour, we were playing Manchester, I think, probably the Apollo theatre. The morning after the show we all arrived back at the theatre to pack up the gear and re-board the tour bus for the next night. Jack, our driver looked a little shocked and told us that the theatre had been broken into during the night and amongst other things, George’s Country Gentleman had been stolen. George, to my surprise, was quite unfazed. “Doesn’t matter. Who cares,” was his attitude. “They’ll send me up another.” To me, the loss of your very own guitar is like losing a member of your family and in no uncertain terms I told him how I felt about his attitude. We had a bit of a barney about that. Anyway, when we arrived at the next town on the tour, a policeman was awaiting the bus with George’s Country Gentleman slung over his back. Looked kinda funny – with his Bobby’s helmet and all! He explained that the guitar had been found only a few blocks away from the Apollo theatre, just hanging on the wrought iron fence of a church graveyard. Maybe the thief had second thoughts. Who knows!

Another iconic date on that tour was November 22nd. We had played at The Globe Theatre in Stockton that night, and when we got back to the hotel, somebody switched on the TV in the bar. An announcer informed us that Kennedy had just been murdered.

Soon after Vox started making solid-state amps, circa 1964, a pair of Vox Super Transonic amps was manufactured and given to the Jaywalkers to try out on stage. I believe they were the only pair ever to leave the factory. They were essentially fully-working prototypes which were given to the band to test on the road. After a quick trial, we found they were unsuitable for public consumption and for any kind of bass or low-end instrument because of their small 3-inch tweeters. They were barely passable for lead guitar and rhythm guitar. We used them on tour for about a week before shipping the remains (I think in a coffin) back to the Vox factory in Dartford along with our disgruntled evaluation: In comparison to the trusty AC30s, they were a load of crap. The transistor amps sounded distorted, toneless, thin, and nasty. The tweeters soon blew, the chrome hardware broke, the counterweights fell off, the casters broke, and the fuses continually blew. Even the Vox logo fell off. Needless to say, the model never went into full production. The two 12-inch speakers in the lower cabinet were whatever Vox was using at that time in its AC30s. However, the Super Transonic looked really cool. The amp and speaker cabinets were covered with the same orange vinyl cloth that was used later on the Vox Continental organ. The grill cloth was a light beige. The two tweeters were housed in circular chrome balls, balanced by a solid counterweight. They would rotate horizontally but not vertically.

Vox had made a valiant but failed attempt to enter the cool. Like many other musical instrument manufacturers who over the ages have unsuccessfully tried to expand into new waters, it may have signaled the beginning of the end for the company. They panicked with more untoward and preposterous products such as the Electric Conga Drum which also has a story. It was essentially an oblong black vinyl-covered wooden box with nothing but a microphone inside – and it had its own chrome stand. Of course, it sported the Vox logo. My next band (The News) took one of these to Thailand in 1969 (we were touring the US bases, working for the Vietnam GIs). Firstly, the drum got lost by Alitalia airlines and never arrived with the rest of our equipment in Bangkok. A few weeks later, Vox sent us a replacement and we used it for such silliness as 50-minute jams on ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,’ complete with Electric Conga Drum versus Electric Wah Wah Sitar solo battles. The drum acquired the name The Electric What because GIs would come up to us on stage and ask, “What’s that box you were beating on?” We’d tell them, “It’s an Electric Conga,” and they would say, “An electric what?” We also were privy to some of the very first Asian guitar and amp knock-offs. Most of them were quite dreadful and fairly obvious to any experienced picker that they came from coconut trees. They certainly wouldn’t get past George Gruhn – even at closing time. However, some GIs were fooled and bought them real cheap from the PXs. Many ended up back in the USA.

Vox also issued a small number of ribbon microphones. Many of you may have noticed pictures of English beat groups on stage singing through these oblong-looking mics. They were actually manufactured by the Reslo company, but Vox affixed their logo sticker onto a select few. They sound excellent with warm, delicate resonance. The only drawback is that ribbon mics are very fragile and don’t hold up well to the rigorous road life. You can break the ribbon even by blowing into the mic. Our band would go through a couple of dozen of these every year. I still have one of these Vox/Reslos in my studio that I use on occasion for special sounds. It works nicely miking a low-level Fender Deluxe Reverb, off-axis, from a distance of about twelve inches.

Upon hearing of our disappointment with the Phantom guitars as well as the Martian amps, Vox invited the whole band to visit the factory one afternoon. I remember getting excited seeing the Phantom guitar-organ on the workbench, but it wasn’t quite ready for a test drive that day. The Vox people served us tea and proudly gave us a tour of their factory. We left with a van full of goodies, including about eight guitars and the same number of AC30s. They also supplied us with a hefty PA system that we would use on the dancehall circuit. This system had a pair of Vox columns containing about six tens in each and a complementary mixer/amp of substantial wattage. All this gear was sufficient for a couple of long, arduous tours. We were working over 300 nights per year. It was during one of these tours that the infamous Phantom javelin incident occurred. As a result, Vox crafted a replacement, a unique pair of Phantom guitars that looked identical from a distance but featured Fender Strat pickups and cleverly disguised Fender necks with the Phantom headstock glued on. Needless to say, they played and sounded great.

I later heard that when news of the hybrid Vox guitars with modified Fender parts reached Leo’s ears at Fullerton in California, it immediately led to the cessation of the import license to JMI, and Vox lost the Fender contract to Selmers, located just two shops down on Charing Cross Road.

Has anyone ever pointed out that that particular stretch of Charing Cross Road, near Cambridge Circus, was home to The Big Four? Annello & Davide, Jennings, Cecil Gee’s, and Selmers—everything a rocker could ever need: Beatle boots, fancy stagewear, amps, and guitars. It was right across the street from the Pussycat porno theatre and a great pub, the name of which presently eludes me.

Such one-of-a-kind incidents were not uncommon in those days. The early Shadows, after discussions between players and Vox engineers, received AC30s with extra tone controls installed on a white panel cut into the back of the amp. This gave the players a much broader tonal range and allowed the Vox to mimic a Fender Bassman if desired. Many budding Hanks across Britain wondered why their salmon-pink Strat and AC30 didn’t sound like Mr. Marvin’s. It took Vox a couple of years before implementing this treble boost into the top panel for the general public. (In fact, the original circuit wasn’t just a treble boost but also included a bass boost and a midrange cut—borrowed from Uncle Leo’s Bandmaster circuit with three tens.)

The AC30s not only suffered from overheating even during brief periods of use but also occasionally smoked and burst into flames. We learned to use the standby switches whenever possible. Additionally, the cabinetry left much to be desired. After twelve months on the road, being tossed daily into the cargo hold of Timpsons’ tour bus by our cigar ash-drenched driver Jack (ex-wrestler), the mortise-and-tenon joints gradually began to come apart due to overheating. I remember one day picking mine up and the handle and top just popping away from the rest of the cabinet. Never mind—call Dartford.

Even Paul would agree that the T60 was less than satisfactory for bass. Dave Denny would crucify me—bless his soul—but let’s be honest: the AC30 was king. The rest was rubbish. Vox should have stuck with their valve amps, and Jim Marshall might still be trading used gear in his Hanwell shop. But this happens to all companies: Gretsch got Baldwinized, Fender got CBS-ified, and the only true believer was Gibson—even though they faltered for a while when Kalamazoo raised the rebel flag in Tennessee. Let’s not even get into the later Asian artifucks. Most companies, other than Fender and Gibson, had a couple of winners and a bagful of losers. Now, I don’t expect all the major guitar companies to come knocking at my door for design ideas after this story—you know why? Because they’re all run by corporate penny-pinching, polyester-suited clit-twits who don’t really know the difference between a G-string and a Vegas dancer. It’s always been a torrid tale of misled marketing.

I don’t have much to say about Vox guitars that couldn’t be summed up in a single word. That’s why you see very few of the famous ’60s beat groups using them. They were basically starter guitars for younger, local bands who couldn’t afford anything better.

The Jaywalkers now had a couple of long tours under their belt and a second summer season coming up. (A summer season was a thirteen-week gig in one of the many seaside theatres around the country where folks would vacation for a fortnight.) A major-label recording contract was also in the works. I decided it was time for a real guitar. AN AMERICAN GUITAR! I spotted a two-tone green Gretsch Anniversary while strolling around London music stores with my girlfriend Kathy one Monday afternoon on April 30th, 1962, to be exact. (You don’t forget your first time!) It sat in Selmer’s window. It was love at first sight. She dragged me away, and we walked into the 2 I’s coffee bar in Soho, but I couldn’t get it out of my mind. Kathy went home at 3:30 PM. The next morning (May 1st), I waited for the shop to open, and for £159, Henry had a new home. That night on stage at a dance hall gig in High Wycombe, I made my debut. I remember being a little disappointed because my Hilotron pickups weren’t as strong as my Hofner Verithin’s, although my tone was magnificent. A few months later, George pointed this out to me after he’d used Henry on stage a couple of times: “Trade the Hilotrons for Filtertrons,” he said. Yeah, sure! Finding Gretsch parts in England? No way! (Both George and John would occasionally use Henry on stage when their own instruments were out of commission due to broken strings, etc. This was long before anybody had the luxury of roadie guitar techs.)

All I wanted to play with my new guitar were Chet Atkins and Duane Eddy tunes. Luckily, such songs were in the Jaywalkers’ repertoire. Henry was my ONLY electric guitar for the next 35 years until 1980 when I needed the sound of a single-coil pickup solid-body guitar for a particular album. So what did I do? I built one! Of course, this was with Henry’s full permission. But Henry can be heard on hundreds of my recordings. There aren’t many guitar players who can truthfully say they’ve been faithful to the same guitar for 60 years. So it wasn’t just a May Day madness fling!

By late 1965, I eventually grew tired of the incessant road work and quit the Jaywalkers. But not before I had made plans for a solo career. I was replaced by Terry Reid, who became the guitarist for the group’s final year before they hung up their rock and roll shoes and disbanded.

Could you share how The News came about, and also detail your journey into becoming a recording engineer and record producer, including some of your early projects? Additionally, could you describe your experience releasing singles in the 60s under the name Big Boy Pete, reflect on the original 60s English rock scene, recall touring with famous bands, and share any standout memories from those days, including your experience working on ‘Cold Turkey,’ which I assume was your biggest hit?

After leaving the Jays in 1965 and signing with Columbia as just Miller, I released my first solo record ‘Baby I Got News For You.’ Back in my hometown Norwich, I formed a new band, the Fuzz, and purchased a 50-watt Marshall half stack. I was never totally happy with the sound; the marriage of Gretsch and Marshall was not made in Heaven. A Selmer fuzz box, Vox wah-wah, and DeArmond 610 pedal helped the mismatched couple. They resided for a few years at my unBeatlebooted feet.

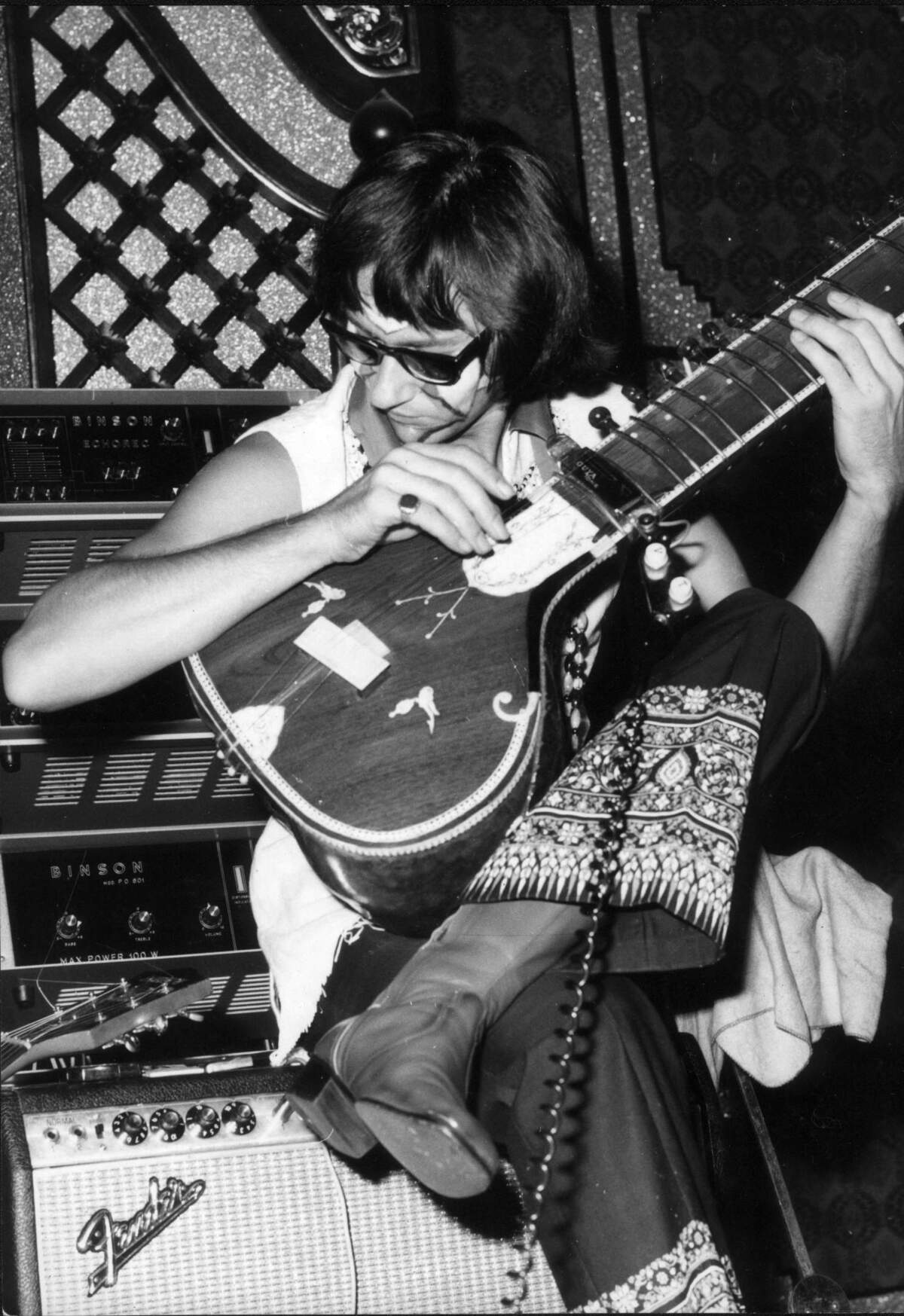

One day my music publisher called. He was producing a record and wanted my unique violin/guitar sound on a recording. The sound of this setup can be heard on The Magic Lantern’s recording of ‘Rumplestiltskin.’ So I humped my guitar and all my unique recording stuff onto the bus to the Norwich train station, then across London on the underground to the Regent Sound recording studio on Denmark Street (where they used the larger gold-coloured Binson Echorec for studio echo) to play the lead guitar part on the Lanterns’ song. (I got five pounds for my trouble). The skullduggery of copyright pilfering would snakedance indelibly into my lobes before the pentade was over.

While in London, I heard of an Abbey Road BTR-1 tape recorder that was looking for a new home. It weighed about 400 lbs. We actually loaded the monster EMI machine into the trunk of my drummer’s Jaguar car (of course, the door wouldn’t close) and drove it back to my home with the car riding at a 15-degree angle. The machine was far too heavy to get upstairs into my bedroom-studio, so my mother kindly allowed me to move the studio downstairs into the lounge – which was sizable by English standards. We pulled a curtain across that corner of the room when guests were due to be entertained. It actually worked out well because Dad’s upright piano could now be implemented on my recordings. He wasn’t too keen on the thumb tacks I installed on the hammers. I told him to imagine he was playing a well-tempered clavier!

I was still with the Jaywalkers when I wrote ‘Baby I’ve Got News For You.’ I offered it to them and they didn’t like it, so I recorded it surreptitiously in the summer of ’65. You couldn’t record at Decca or Columbia unless you were signed to them, so I went to a private studio: R.G. Jones, in Morden, Surrey, and made the record there. That studio has now reached a legendary status because many famous artists cut their teeth there. Some demos were produced on the Oak label and I got signed to Columbia. The record was released October 29th, 1965, and that’s when I quit the Jays. The guys who backed me on the record were members of The Herd, including Peter Frampton, Andy Bown, and Mickey Waller on drums. They were all pals of mine at the time. The single was released under the name Miller. Alas, my ferociously fuzzy guitar riff and Troggsy snarl — which earned the single the arguable title of first British psychedelic tune ever — was far too rough for the Mersey-sweetbeat public.

I undertook a few solo appearances to promote the record at such places as the Marquee on Wardour Street, Hammersmith Palais, and the 100 Club on Oxford Street, and also did a live broadcast for Radio Luxembourg. This record has been re-released on numerous independent compilation albums. It has also been bootlegged by a French record company with an exact look-alike Columbia label, so collectors beware!

I was living in a flat on Randolph Avenue in Maida Vale, London through March of ’66 writing songs. Although I had written some instrumentals for the Jaywalkers, my first vocal composition was a little love song called ‘Time Has No Meaning When You’re Young,’ which had been hanging around in my brain since 1964. I decided to take this song to a London publisher, Mike Collier at Campbell Connelly, and fortunately Mike fell in love with it and not only published it, but offered me a house-writer’s contract and retainer. And that was the start of my career as a tunesmith. My songwriting skills rewarded me.

Word soon got around that I was now a gun for hire. With my solid guitar-playing reputation, I began doing extensive work as a studio session musician in London, playing on dozens of records for other folks during that golden era of British pop. The sessions were so fast and furious, I don’t remember hardly any of them. But I do remember one thing, I was doing a lot of ska and bluebeat stuff with Jamaican artists like Millie, those kinda people, and some English artists who were trying to jump onto the bandwagon. Alan Caddy, the lead guitar player from the Tornadoes, was doing some producing in those days, and he used me on a lot of this stuff ‘cause it was beginning to get real popular. I remember that after three hours of bopping up and down to that ska rhythm guitar backbeat, when I left the studio, I’d lope down the street nodding that incessant rhythm like a deranged wino. I had developed the bluebeat rhythm by that point, so if producers wanted that style I would get called in. I thought I might have been able to make a living out of doing sessions, it was fun but it was tough, I was getting about 5 quid for three hours work. One non-bluebeat session I do remember at Regent Sound was playing a fuzzy violin-sounding lead guitar for the Magic Lanterns on their song ‘Rumplestiltskin.’ I even contemplated working with Jerry Dorsey (later Engelbert Humperdinck). Jerry had a 12-week gig lined up somewhere in the South of France and did a couple of rehearsals with him before deciding that this was not the avenue to pursue.

Somewhat disappointed by the rigors of the star-making machinery, and deciding that five years in London was enough (1961-1966), I quit my flat in Maida Vale and returned to my hometown Norwich to churn out hits for the stars. Here I could channel all my energy and concentration into being a staff writer for the music publishing company that had signed me.

Which brings us into the beginning of the Big Boy Pete psychedelic era. Or as I used to call it – Psychobollux. Endless touring had taken its toll, and finally, freed from the road, this burned-out musician sequestered himself in his home studio in Norwich. Under the spell of psychedelic-influenced albums such as the Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and the Rolling Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request, I wrote and recorded hundreds of tracks over the course of the next three years and Big Boy Pete was born. Comparisons to tracks from these classic albums are inevitable and I unashamedly admits to the influences.

Although my songs owe a great deal to British psychedelia, my rocking roots poke through on many cuts where I mix fuzzed-out wah-wah textures with rockabilly-style solos and raving rock breaks through from time to time. Then I toss aside my roots-rock influences and unleash lewd ring-modulated fuzz squawks that presage Adrian Belew’s animal calls. My recordings are full of well-conceived guitar parts developed through the process of letting the tune do the talking. I always get my inspiration from the song and what the song calls for, then I try to come up with something appropriate.

Although most of my songs were recorded at my home studio, some I taped at Advision studios in New Bond. Others were cut at R. G. Jones, Regent Sound, and Olympic studios. But back in Norwich, I was able to do what I liked best – writing and recording. From my studio at 22 Margetson Avenue, Norwich, surrounded by lava lamps and Hindu visuals, literally hundreds of recordings were completed between 1966 and 1969, including ‘Cold Turkey.’ Many of these, rejected at the time by the London publishers as being too far out, are now available for the very first time.

Of the 100 or so songs that were published by major publishing houses in London, fewer than 20 were actually picked and recorded by established artists. Freddie and the Dreamers, Sounds Orchestral, Boz, and The Knack were just a few of the artists who recorded my compositions. More recently, The Damned covered my song ‘Cold Turkey’ on their Nazz Nomad and the Nightmares album. Also, The Bristols did great versions of ‘Baby I Got News For You’ and ‘My Love is Like a Spaceship’ (The B-side of ‘Cold Turkey’). A New York band, the Squires of the Subterrain, was so taken with my sixties tunes that they released a complete album of fourteen never-before-heard Big Boy Pete songs entitled ‘Big Boy Pete’s Treats.’

Frequent trips to solicit the music publishers in London’s Tin Pan Alley (Denmark Street) found me often hanging out in the infamous Giaconda coffee bar with my equal-opportunity, clap-happy girlfriend Maria who worked there as a waitress. One lunchtime an informal jam session took place in the upstairs studio of one of the publishers’ offices with me, Clapton, and Page exchanging licks.

For you hi-finatics, the equipment in my Norwich studio consisted of the following: For tape recorders – Vortexion, C.B.L, Bang & Olufsen, Brenell, and later, an old mono monster EMI BTR-1 which I got from Abbey Road studios. Being limited to two-track recorders at best, bouncing signals between machines gave multitrack capabilities. Up to nine bounces were achieved on some songs before severe signal degradation (and tape hiss) prevented further. Tape speeds of 15, 7 1/2, 3 3/4, and even 1 7/8 inches per second were used to produce various delays of slap-back echo. Other echo devices included a Binson Echorec, Watkins Copycat, and a couple of Farfisa spring reverb units to achieve stereo reverb. Extra reverberation was acquired by commandeering the bathroom as an acoustic echo chamber, and also the underground concrete-walled bomb shelter from World War II, which was buried in my back garden. A visiting producer once remarked that it may have been illegal to have so many echo devices in one place!

Signal processing options were limited. A custom-made six-input mixer (with no EQ) linked to a single-channel RCA Orthophonic equalizer provided frugal mixing power. The monitor system consisted of a Norwich-made HACO amplifier linked to a pair of Golden Wharfdale speakers. Two local electronic wizards – Granville Hornsby and Tony Howes built me a couple of unique effects boxes (the Goobly Box and the Humbert Humbert) with which some unprecedented sounds could be created. The sound of a monophonic synthesizer was simulated by hand-twisting the oscillator dial on a Honor sine wave generator. I discovered that the recognizable Joe Meek sound (squashing signals through a Fairchild 670 compressor) could be simulated by carefully overloading the valve pre-amps of certain tape recorders, hence saturating the tape.

Studio instruments included Fender and Marshall 50-watt half stack amplifiers (No Voxes – I had had enough of them from my Jaywalker days), also an upright piano with tacks in the hammers, a Fiesta red ’62 Fender Precision bass, electric violin, electric sitar, wooden flutes, various percussion instruments, Levin acoustic guitar with DeArmonde pickup, and of course Henry – my trusty Gretsch guitar, which I still play to this day.

Many of Norfolk’s local bands also recorded demos at my recording facility, and I helped local songwriters get their works published through my contacts. But writing and recording left a void, and I needed to play live. So, after a few months, in the summer of ’66, I formed a new band called The Fuzz. Probably my most favorite band, ‘cos we did all the old fifties rock ‘n’ roll stuff that I loved – Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee, Larry Williams, etc. Yeah, we rocked. Although they called me Big Boy Pete on the record label, The Fuzz were actually the guys that backed me on ‘Cold Turkey,’ which was released a couple of years later. Sadly, the band was short-lived because we refused to play the hits-du-jour. Gigs were few and far between, so when another local band called The Continentals offered me a job, I decided to go with them. The Fuzz only lasted three or four months, and The Continentals disbanded after about the same amount of time. The Continentals later changed their name to The News.

Around Christmas time, I went to work at this club on the rural outskirts of Norwich at the now infamous Washington 400 Country Club. Actually, it was a gambling casino with a restaurant and a hotel, frequented by traveling salesmen and dodgy underworld characters. The club put on a little cabaret show twice a night with striptease, singers, and maybe a magician or a comedian. It was a bit like the working men’s clubs from Northern England. I played in the house band for the shows and then for general dancing. We would do a lot of Jimmy Smith kind of stuff, Stones, Mose Allison, anything. It was a very easy gig. We could play whatever we wanted. They didn’t give a damn. They just wanted to see the tits. I would go there five hours a night, hang out with the strippers, smoke hash, drink barrels of beer, get in loads of trouble, and then go home and write songs before hitting the sack. Then I’d get up at the crack of noon, go to my studio and record them. It was almost like a regimented procedure five or six days a week. Some weeks I’d complete ten or more songs. Incidentally, the song ‘Pig’ on one of my albums was about Roy Dashwood, the club owner. Over the next two years, as personnel came and went, I played in various incarnations of the Washington house band – The Paul Saint Trio, Peter London Trio, SNAFU, and finally The News.

My songs have been re-released on many compilation albums such as the Electric Sugar Cube Flashbacks and Pebbles compilations, sparking several “Where is he now?” items in Melody Maker and other music publications. People are still arguing about who Big Boy Pete really is. First I was Peter Miller, then Buzz Miller, then just Miller, then Big Boy Pete, then just Buzz. It’s not surprising there’s some conjecture as to who I really am. Now I’m back to Big Boy Pete again!

But the dozens of psychedelic and pop songs I wrote in this period were nothing compared to my masterpiece, ‘World War IV,’ my concept album about the end of the world. Over a year, I labored at crafting a multi-layered, hallucinatory work that would stand alongside Sgt. Pepper, the Stones’ Their Satanic Majesties Request, and Jimi Hendrix’s Axis: Bold as Love. In response to numerous requests, I have finally put the complete lyrics to ‘World War IV’ up on the internet. Spread the word! Here is the link.

I was writing most of my songs for commercial reasons, with the charts in mind, or what I perceived were commercial reasons. I was basically trying to get a hit record. Finally I got tired of churning out this pop and turned to my publisher one day and told him, ‘I’ve done what you wanted for the last two years, and you haven’t got me a chart topper, so now I’m gonna do something that I want to do. And I don’t give a damn if you like it or not, but you’ll have to wait about a year, and then I’ll play it for you.’”

So I went to live in a little flint cottage in the village of Fritton, about 15 miles outside of Norwich, and began to compose the piece around March of ’68. It was completed in March of ’69, having taken three months to write, and then nine months to revise, rewrite and record. It was rather an ambitious undertaking given the limited amount of recording equipment I had at my disposal, and, except for a couple of musicians that played on “The Overture” section, it was all me – multi-tracking. The work lasted 45 minutes and I called it ‘World War IV — a symphonic poem.’ When completed, I took it to my music publisher, who listened to it and said, “Ooookay — What am I going to do with this?” “That’s your job.” I told him. “Well, leave it here,” he said. Somehow he got it over to Apple publishing and John Lennon liked what he heard and wanted to put it out on the Apple label.

Meanwhile the road beckoned once more. For a long time I had wished I could go to America to play with American musicians, but getting there wasn’t easy. Not surprisingly, I took the long and scenic route. This included a three-year layover in the Far East entertaining the Vietnam G.I.’s before finally landing in – of course – San Franfuckingcisco. Where else could this petal-pushing, peace-pooping psychodaisy end up? And this is how it all came about:

Back at the Washington Club in Norwich, the band were all thinking about getting out of England. We were bored with the scene and disillusioned with the way the music industry had turned and all wanted something exciting and new to do. So one stoned night, we cooked up a crazy idea. We planned to pack everything into a small wagon and drive overland from England to Thailand. Ten thousand miles through God knows how many weird and dangerous countries: Turkey, Iran, Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Burma, not to mention all of Western Europe and some communist Russian satellites. Stupid idea, right? But we were gonna do it. “That sounds like a good idea. OK, let’s do that, we’ll get a hold of a bus and we’ll drive to Thailand, and we’ll go play over there.”

And this is how it went down: A buddy who was a waiter at the Washington club had come from working in the African Congo as a mercenary soldier. I had sold medical supplies for profit to some insurgent guerilla army or another, so was quite knowledgeable about medical needs, diseases and survival techniques in inhospitable lands. And by pure coincidence, he was also planning on making a similar trip to Thailand and was gonna hitch-hike overland.

On his advice, I wrote for donations of prescription drugs from drug companies, and concentrated high protein food supplies that would get us through what we anticipated would be a six-week expedition. Then, upon our return, we intrepid heroes would endorse their products. Next we bought a Land Rover, decided it was too damned uncomfortable – no springs on the seats or anything. So this bunch of wimpy musicians tried out a VW bus and liked that much better ‘cos it had soft cushioned seats and beds. Then we thought that we should do a test trip to make sure this was all going to work. “Let’s load everything in the wagon as if it’s the real trip, and just drive around France for a couple of weeks.” This actually made sense because we knew that once we got out there as far as Istanbul, from there on out, if something went wrong, we were dead meat. But it turned into a total disaster long before Istanbul.

So my drummer Robert and I loaded up the VW, drove to Dover, and crossed the channel to France. It was late in the day when we landed, so we just drove about ten miles inland and parked for the night in a country lane. We cooked up some Veraswamis Indian curry, smoked some hash, and went to sleep. So far so good. The next morning I said, “We gotta go get some wine and food from the local market.” But we slept late, and that day all the stores happened to close at noon, so we couldn’t get any wine. So we just drove around for a few hours and found another rural camp spot. The next morning, up bright and early, I said, “Now, let’s get some wine.” However, it was a national public holiday, and all the stores were closed again. Bummer. Finally, on the third day, we got up really early, went down to the Monoprix market, actually got there before it had even opened. At nine o’clock, like girls rushing into an after-Christmas sale, we grabbed a whole case of wine, French bread, butter, cheese. “Right. Let’s go party.”

I was driving. Of course we were imbibing from the get-go and about 10 miles outside of the town of Verdun, along a quiet country road, a wine bottle got caught under the clutch, and as I leaned down to pull it out, I lost control and the VW bus skidded, somersaulted about three times and landed about 30 feet off the road in a field which just happened to be an uncleared minefield from World War II. Nobody was hurt but the VW was a write-off. We cautiously tiptoed successfully back to the road, then figured out a safe path and got most of our stuff out of the van. The rest of it was strewn up and down the road ’cause we’d rolled some 70 or 80 yards. The van was obviously destroyed, so we just left it there and sat and waited for someone to come along. No one did for five or six hours.

At least we had some wine and hash, and cooked up some more curry. Finally a farmer came by and gave us a lift to town. From a cheap hotel we phoned our bass player back in England who drove over and got us both back home. So that was the end of the vehicle which was to take us to heaven.

Luckily, a couple of weeks later, I received a very welcome letter. The waiter/mercenary doctor from The Washington club had made it safely to Bangkok. He’d got involved with a Thai movie company, and persuaded the owner that importing an English band to play for the American troops in that country might be a lucrative investment. There were numerous US bases scattered throughout the jungles of Thailand. After a month or so of negotiations, the company, Amthai Films, sent me four plane tickets. (I actually thought Bangkok was Baghdad. Oh well — close enough for rock and roll.) So we finally did get out. And that was it; that was the end of the English thing.

But what happened to my ‘World War IV’ — the symphonic poem that Lennon wanted to release? I pursued initial negotiations with Apple and then when I got caught up in the excitement of learning that I was finally getting out of England, and I knew I wouldn’t be coming back, I lost interest and just dropped the whole idea. But of all the tapes I had made in those seven years of recording, ‘World War IV’ was the only one I took with me. I was real proud of it. It eventually came out in 1999 on Gear Fab records as a CD, then on Comet records as an LP. Both labels were too cheap to enclose the lyrics, so as I mentioned, they’re now up on the Internet.

On July 3rd, 1969, just two weeks before man walked upon the moon, four disheveled, sweaty, disoriented, sparkling non-entities alighted at Don Muang airport, Bangkok and were efficiently escorted around customs and into a waiting Mercedes limousine. Now we’re talkin’!

Amthai had set up a tour of the American bases, which were scattered throughout the jungles. After a couple of quick rehearsals with the blonde Australian chick singer who had big tits and no voice whatsoever, the band did the regulation audition for the US military agency that oversaw the entertainment. After we’d passed the audition, I was presented with their “do not play” list. Certain uplifting revolution-inciting tunes were not allowed to be included in our set list. One was “We gotta get out of this place,” another was Country Joe’s “What are we fighting for?” A third, strangely enough, was “Happiness is a warm gun.” (Wasn’t this part of the soldiers’ indoctrination?) So we asked Why not? We like that song. And they said, You play it, and you’re out of here. They didn’t want us filling their boys’ heads with ideas. After a bout of internal bleeding, the band agreed to disagree and opted to go along with the mandates of the powers that be. After all, we’d come all this way, and although I wasn’t playing in America just yet, the US bases were considered hallowed US territory. Close enough once again.

And so began another grueling tour schedule, this time in the jungles of Southeast Asia. There were about 20 bases scattered throughout the country, with three clubs on each base (enlisted men’s, officers, and non-commissioned officers). The band (The News) would always play all three clubs in one night, a one-hour set in each, then have to sleep in the only “hotel/brothel” in the nearby village — always a rat-infested, cockroach-ridden, filthy, non-air-conditioned ugly piece of concrete which had been hastily erected to service the GIs’ off-base needs. Sleep was near impossible with screaming drunk soldiers and their teenage bargirl dates tearing through the corridors and generally creating mayhem.

Next morning, we would sometimes have to drive for a whole day on dirt roads to get to the next camp. Some of those bases were in very difficult-to-reach places; for example, NKP (Nakhon Phanom) was right on the border with Laos. We would have to leave Bangkok at six in the evening in order to play there the following night; it was a 24-hour drive, and it could reach 120 degrees in the sun. And it’s real jungle out there. There were snakes, monkeys, elephants blocking the road — and, although this wasn’t Vietnam, the Viet Cong were all over the place. Sometimes it was just the occasional sniper fire coming from out of nowhere and hitting the van, which had us running for cover and ducking into the jungle. It was hell on wheels. Sometimes it was face to face. What really mattered was letting ’em know that we weren’t American soldiers, ’cause they’d get paid really well for the dog tags.

One moonlit night, after a gig at the Udorn Airbase, we walked a mile or so out of town, along the banks of the river Mekong into a small village looking for some dope and this drunk VC stumbles over, thinking we were soldiers and excitedly waves his gun at us. Our roadie, who spoke a little Vietnamese kept pointing and pulling at our hair, yelling, “Long hair, no GI, long hair, no GI,” and eventually the VC finally took notice and let us go. We would’ve been dog meat if we hadn’t had long hair. There was a bounty of $50 for every set of American dog tags that a Viet Cong soldier turned in. That was a lot of money to them.

It was kinda scary but we didn’t know what was going on half the time. We’d pay five dollars for two kilos of what they called best Buddha grass, so naturally the memories are a bit wispy to say the least. However, I kept a diary while I was there, and lots of memorabilia.

Musically speaking: Eventually, the heat and the humidity became stifling and my creative juices ceased to flow. Furthermore, the Asian recording industry was, well, let’s just say what recording industry? All they seemed to be doing was manufacturing poorly pressed pirate copies of putrid bubble-gum pop. However, there was a vein of gold — the GIs were bringing over all the best Yankee music, and they were more than happy to share their records with myself and the band so that we could learn this stuff and put it into our act. Yes, we even played a 45-minute psychedelic freaked-out version of ‘In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida,’ during which I played a lengthy stoned-out sitar solo (which sported a crystal pickup, routed through my Vox wah-wah pedal and Selmer fuzz box into my Fender Pro Reverb amp set on 10). There was a gaggle of turbaned Indian gentlemen who would often frequent one club specifically to be amazed and bemused at this Western wanker wah-wahing their national instrument while my drummer accompanied me on a similarly electrified and effected tabla. And the best up-country Buddha-grass dope was only five US dollars for two kilos. You may wonder why we ever wanted to leave all this? Well, in fact, Robert didn’t. He’s still there! And I’ve been back half a dozen times. And I didn’t even mention the gloriously gorgeous bar-girls that were available by the truckload, free to their number-one band boys.

What made you move to San Francisco in 1972?

Would love it if you could share some insight on those lost recordings that were released via Gear Fab?

Did you experiment with psychedelics? Do you feel that it changed your perception on how you approach music making?

There are several releases under your name like for instance ‘Summerland,’ ‘Homage to Catatonia’, ‘Return to Catatonia’, ‘World War IV’, ‘London American Boy’, ‘The Margetson Demos’, ‘The Perennial Enigma’, ‘Merry Skifflemas!’… it would be fantastic if you could share some words about each of the releases.

By 1973, like most rock and rollers in paradise, green pastures beckon and rear their sirenesque heads with a frequency unlike that for any other profession. I had had enough of the Orient and the band disbanded. After two weeks back in England in the midst of a brutal, miserable winter, I decided that I no longer wanted to reside in Old Blighty and finally headed for my dreamland – the USA, where my Hawaiian girlfriend awaited on the beautiful island of Oahu. (Yes, Hawaii is part of the United States of America.) This was the young girl I’d met and stolen from an American lead guitar player, in Bangkok. (Upon discovering the liassone, the American’s retort was “You want my Strat as well?” The hula dancer would later become my wife and that would be my membership card into Uncle Sam’s club.

We stayed in Hawaii for almost a year, until rock fever finally drove us to San Francisco because, beautiful as the islands were, after one year of solid songwriting, and finding little or no music industry connections there, me and my fair lady decided to take the mainland by storm. We landed in Frisco in December 1973, just days after watching Elvis play an incredible concert at the H.I.C. Arena in Honolulu. So I had a bellyfull of songs, a four track Sony tape recorder, Neumann U87 microphone and a Binson Echorec — and a dream to make come true. The tapes started rolling. They’re still running!

Frisco: Busking street musicians that shamed the London session crew with their grooves; North Beach blues clubs wailing like an ol’ steam drill; Broadway’s jazz clubs sending you to swirly clouds of rapture; across the Bay, Bump City’s original black blues boogie boys from the deep South; the psychedelic Winterland, famous Fillmore and awesome Avalon dance halls. And just down the road apiece — Holy Hollywood and Vine, and Sunset Boulevard, and that Taj Mahal of the Barbary Coast — the legendary Capitol Records tower that graced the label of all five of my original Gene Vincent albums. Shangri-La. El Dorado. Now all I needed was a green card to nail my residency to the wall. “I do.” I said happily!

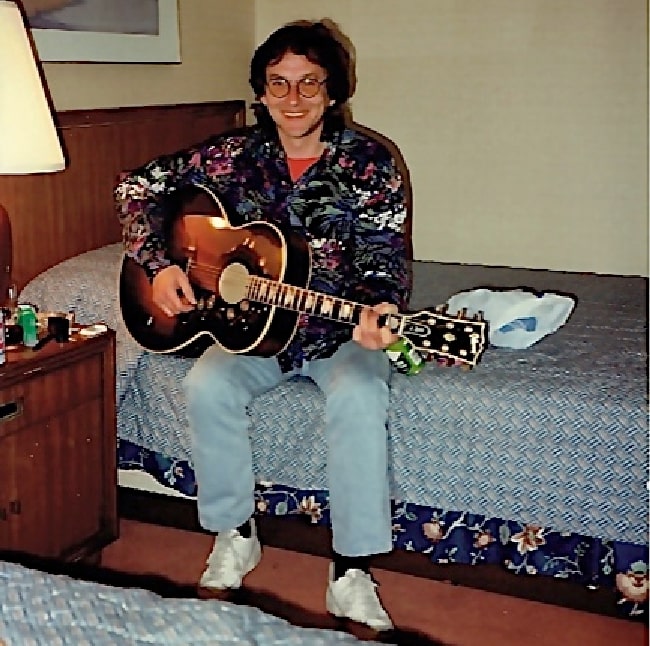

After searching for a few weeks for a suitable location in which to build a professional recording studio, I settled in the Marina district. Built by a musician for musicians, and tucked away in a quiet courtyard between yuppie boutiques and chic restaurants on San Francisco’s famous Union Street, my studio began recording ‘Loud & Proud.’ (My studio slogan). I am is proud to have played a part in the production and success of dozens of albums and singles and countless demo recordings, and I offered a complete production service for record manufacturing and promotion. The studio served as my livelihood and remained in this idyllic environment for almost 25 years. This was the womb from which hundreds of my own masters issued forth, many of which have yet to see the light of day.

I have been responsible for producing and engineering hundreds of American artists and have earned great respect within the industry as both an engineer and producer. Thanks to Joe Meek, I incorporated many cutting-edge recording techniques that I learned from him, applying them not only in my own recordings but also in sessions I produced and engineered for my clients. From jazz to punk and everything in between, starting in 1978 with The Avengers’ initial tracks, I collaborated with dozens of local punk bands. Working with them was a pleasure; they injected life into what was becoming a bland and sterile scene. Once again, punk placed me on the fringes of a musical revolution, but my own albums saw little improvement, falling victim to the “too odd, too soon” curse.

Unfortunately, as my studio became fully operational, the demands of recording other bands forced me to sideline my own music. Nonetheless, I managed to squeeze in occasional sessions. With new bands arriving almost daily, I had the luxury of “auditioning” numerous drummers, selecting those best suited for my own projects. It was a privilege to work with American musicians for the first time. Fans of my sixties songs will notice a stylistic shift in my San Francisco recordings. While maintaining the BBP signature in melodies and lyrics, the musical arrangements were stripped down compared to my previous complex layers; many San Francisco tracks featured only a basic four-piece band without any overdubs.

My early passion for fifties rockabilly is evident in my next three albums. The first, “Pre CBS” by Peter Miller and the Wildcats, released in 1980 on my •22 Records label, blended psychedelic whimsy with raw fifties-style rockabilly, predating The Straycats’ rockabilly revival by a couple of years. The Wildcats and I even played gigs around San Francisco, including the renowned Mabuhay Gardens on Broadway. In 1986, I released ‘Rockin is My Business,’ a pure rockabilly album. A few years later, England’s Raucous Records released a third album of classic rockabilly covers titled ‘London American Boy.’

After cleansing myself of the lingering influence of fifties rockabilly that had gripped me since 1957, I teamed up with Shigemi Komiyama, a talented drummer formerly with Hot Tuna. Together, we recorded an album of Shadows-style surf instrumentals released on Mai Tai Records in 1995.

Next, a trilogy of albums on England’s Tenth Planet label showcased 36 previously unreleased recordings from my Norwich home studio, spanning 1966 to 1969. Released from 1996 to 1998, these albums—’Homage to Catatonia,’ ‘Summerland,’ and ‘Return to Catatonia’—revealed my evolving style.

In 2000, San Francisco’s 3 Acre Floor label released a Big Boy Pete 45 rpm single featuring two more sixties tracks: ‘Me’ and ‘Nasty Nazi.’ The latter was penned in 1968 as a response to ‘Cold Turkey,’ aimed at ending my contract with Polydor Records, a German label that had released ‘Cold Turkey’ under the Big Boy Pete name without consulting me—a move that had irked me considerably.

Finally, in 1999, Gear Fab Records and Comet Records unveiled my masterpiece, ‘World War IV – a Symphonic Poem,’ originally conceived in 1968. Three months to compose and nine months to record, this 46-minute opus was once considered by John Lennon for release on Apple Records. The album’s cover featured original artwork commissioned from a Norwich painter, the heroin-addicted girlfriend of my former band’s piano player at the Washington Club.

By summer 1999, after 25 years on Union Street, I made the decision to close my studio, moving all its contents—soundproofed walls included—to my new home near Ocean Beach in San Francisco’s Outer Richmond district. Since then, my recording activities have been limited to occasional sessions with friends, including Rambling Jack Elliott and Arlo Guthrie.

The new millennium marked a shift in my musical direction as I began collaborating with various artists. First, psychedelic albums with The Squires of the Subterrain, a project led by New York singer-songwriter Christopher Earl, revisited unreleased BBP compositions from the sixties on Rocket Racket Records: ‘Big Boy Pete Treats’ and ‘Hitmen.’

Another fruitful collaboration, this time with bassist Bill Bonney (formerly of the UK band The Fentones), produced three albums of fresh surf-style instrumentals crafted specifically for the esteemed US label Double Crown Records: ‘Rock-Ola,’ ‘Bang It Again,’ and ‘Play Rough.’