Schroeder Roadshow | Interview | Rich Schwab

Rich Schwab’s musical journey is a dynamic evolution of unfiltered creativity, starting with his early bass work in bands like Eiliff, where he delved into psych and jazz rock.

From his early days thrumming the bass in bands like A Group, A Group II, Circle Line, Action Set, Mhagara and Eiliff, where he wove psychedelic and jazz rock into his DNA, to the explosive arrival of Schroeder Roadshow—a band that fused gritty rock and anarchic comedy into a frenzied spectacle that left Germany buzzing. Their live shows were a whirlwind of raw power and absurdity, every performance a testament to the band’s electrifying chaos. Despite the relentless grind of touring and the inevitable clash of artistic egos, Rich never lost his drive. He continued to churn out records and collaborate with a parade of notable acts. By the mid-’80s, the landscape shifted, and Rich navigated through various projects and creative endeavors with a fervent curiosity. Today, he’s immersed in writing and music production, reflecting on his tumultuous journey with a blend of nostalgic reverie and unquenchable forward-looking ambition.

“Every Schroeder gig was unpredictable”

You grew up in Cologne? Would you like to discuss some of your very early days growing up in the city and what it was like for a young kid in post-WWII Germany?

Rich Schwab: I was born in 1949 and grew up in a pretty poor suburb, in one of a hundred small cooperative houses built in the ’30s. Each had a little garden with vegetable patches and a few fruit trees. I was the only child in our family; my father was absent. When I was 4 years old, my grandmother took long walks with me to the inner city and showed me the ruins the war had left behind. By the early ’50s, the city didn’t look as devastated as it did in 1945 anymore (photos from that year show a huge landscape of bombed-down houses, with just the cathedral standing there in the center, miraculously undestroyed…), but there were still ruins everywhere.

To me, these sights were both shocking and fascinating: great parts of our hometown were one gigantic, adventurous playground, and all the stories about the horror and cruelty of war couldn’t keep us kids from playing war games in these destroyed areas. Neither could all the warnings that there was lots of unexploded ammunition under the debris. In fact, in those days, more than a few kids died after finding bombs and hand grenades and playing with them.

Growing up in the ’50s in Germany, on one hand, was living in an atmosphere of freedom – all the adults were so busy cleaning up the wreckage, rebuilding their cities and homes, finding ways to get paid jobs, and regaining prosperity that they had no time to take care of their numerous straying kids. On the other hand, the overall mood was sort of dull and gloomy – nobody was willing (or capable) to speak about the war and the guilt this whole nation had incurred.

Many of the elders were ex-Nazis, especially the men with official jobs – policemen, janitors, teachers – and they still behaved like Nazis. Arrogant, very authoritarian, and prone to violence. That provoked a growing anger in our younger, post-war generation, an anger that exploded in the ’60s, when we just couldn’t bear this oppression and mendacity anymore and started to protest and resist. One outstanding symbol was letting our hair grow – something that outraged these people more than a lot of much more important but less obvious things. As a youngster, more than once I had to fiercely fight to keep completely unknown people in the street, in public buses, or bars from tearing my hair out or trying to cut it.

Was there a certain moment in your life when you knew that you wanted to become a musician?

As a kid, I spent a lot of time alone at home, locked in so I couldn’t get out and fool around. My only companion was this huge old radio. One result was my early sympathy for the English language – those AFN, BBC, and BFBS speakers sounded so much friendlier than their colleagues on the German radio stations. The other thing was that I heard a lot of music – and I loved music. Classical pieces, operettas, pop (“Schlager”), jazz… When we were asked at kindergarten what we wanted to be when we grew up, my answer was “a trumpet player.” Or a singer – my absolute favorite when I was 4 or 5 years old was the song ‘Nimm mich mit, Kapitän, auf die Reise’ by German actor Hans Albers (“Take me with you, captain, on your trip”). That song made me cry every time I heard it, and it was on heavy rotation back then. It filled my heart with a mixture of homesickness and wanderlust, and it planted the wish in me to become a musician too, and one day be able to evoke such emotions in other listeners.

How did you first get involved with music? What were some of the main influences for you? Did you listen to Radio Luxembourg? Where did you usually find new music in those early days?

One of my uncles played the guitar, mostly old German folk songs, and another uncle played the accordion. They played together at birthday parties or other family gatherings, and everybody sang along. Unfortunately, I was not allowed to touch their instruments; these guys were afraid I could damage them.

Every couple of weeks on Sunday afternoons, my mother took me with her to a dance hall in the city where small orchestras played, and people would dance foxtrots, tangos, and waltzes. The women going there were allowed to spend all afternoon with a small bottle of lemonade or cheap white wine and wait for devotees who would ask them for a dance (there were, of course, many more women than men, not only in these establishments, with all those absent men).

Whenever possible, I insisted we sit at a table near the band’s drummer, and for the next 3 or 4 hours, I was fully occupied listening to and watching these artists play. Those bands mostly had a piano, bass, drums, and a three-piece horn section line-up, sometimes an additional guitar player or a violinist. They played very mellow, Glenn Miller-like, danceable jazz music, with the drummers most of the time playing with brushes. But I loved it. And my future plans said goodbye to the trumpet and settled down on a drummer’s stool.

Radio Luxembourg came much later. I didn’t get to hear it very often – what was played there, my parents derogatively called “Negro music” or “jungle noise.” But for my 14th birthday, my grandmother bought me a tiny little transistor radio with batteries – finally, I could listen to Rock ‘n’ Roll late at night, secretly in my little room, under the blanket.

An everlasting memory of mine is of an afternoon when my mom and stepfather were out somewhere, and I lay on my bed reading Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath – and the radio played Chuck Berry’s ‘Memphis, Tennessee’: what a perfect fit…!

Of course, Radio Luxembourg was a main source for finding new music, and there was AFN. Then there was BFBS with the ‘Saturday Club,’ where they introduced new records on Saturday mornings. Not the best time to listen with the parents being at home. Luckily, a classmate of mine had a Grundig tape machine, he recorded the Saturday Club and the Hit Parade, and I used to visit him before school, and then we listened to these shows – and, of course, we were constantly late for the first lecture.

The Hit Parade on Radio Luxembourg came on Sunday at noon. A very inconvenient time – that was when we had Sunday lunch. I’ll never forget the Sunday (I was 16 by then) when the Hit Parade host announced a new single by a promising young guitar player – and the guitar intro of Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Hey Joe’ exploded into our kitchen. I immediately jumped up and turned the radio volume up – and got beaten up by my stepdad because it took me too long to turn it off again…

Last but not least, there were two or three record shops in Cologne where one could listen to new records at a headphone bar. But, of course, you were asked to leave if, after listening to more than five records, you still hadn’t bought one. Singles were 5 Deutschmarks then – and my pocket money was 2.50. A week… LPs were utopian.

One of the very first bands you were part of was called A Group, A Group II, Circle Line, Action Set, and Mhagara. Could you tell us what your repertoire consisted of in those bands, and please connect the dots between them? Did any of those bands release anything or at least record some material that remains unreleased?

When I was 12, maybe 13, our high school had an exchange student project, and a couple of Americans stayed for a few weeks (or months?). A handful of them had a skiffle band and were allowed to rehearse in the music room. Whenever I got the opportunity, I was there and listened, drumming with my hands on my thighs. Then their washboard player broke his arm (no, I was not involved), and they let me take his place – that was the start of my career as a musician.

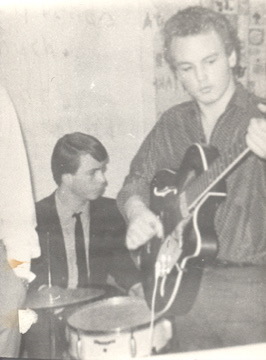

A Group was the band I formed with my two best friends, classmates who, of course, had the same musical taste as me. They both played guitar; one was a year older and much better than the other, and he had an elder brother who regularly traveled to London and brought back new singles and issues of the New Musical Express and the Melody Maker. Seeing pictures of the English beat bands and listening to them, we decided to have our own band. So I became the drummer, my drum set consisting of a snare and a hi-hat. We played ‘Needles and Pins’ and ‘What Have They Done to the Rain’ by The Searchers, or ‘All My Loving’ by The Beatles. And yes, even ‘Blowing in the Wind’…

Then ‘The House of the Rising Sun’ landed on our record player. We immediately realized our repertoire was much too soft and decided to go much harder. And that we would need a bass player. Hardly anyone played bass in the Cologne beat scene. What we found was a drummer – he even owned a complete Sonor drum set, with three toms and all – and man, could he play! One rehearsal with him, and I was condemned to become the bass player. My first bass was an acoustic western guitar with the two upper strings removed. We installed a cheap pick-up, and I played it over a huge old tube radio – that year, I must have shredded at least half a dozen of these radios.

The next year, I spent my six-week summer holiday unloading fruit trucks at the local market hall and was able to buy a “Corina” bass at the Hertie warehouse that cost 249 DM. We also recruited a harmonica player who actually was not very talented – but he owned a Schaller bass combo amp.

A Group was an exception among the other Cologne beat bands because of our rough and dirty sound and our exceptional repertoire – we played songs by The Rolling Stones, The Small Faces, The Pretty Things, The Animals… and Them. Singer and songwriter Van Morrison would accompany me throughout my whole life, with ‘Astral Weeks’ being my all-time favorite, a record I bought at least three times on vinyl when the needle had perforated the older one, and I have it – you never know – twice on CD. (And, of course, as MP3 files on my hard disc jukebox.)

We rehearsed like mad, with bleeding fingers (forget school and homework!), and very soon had gigs and a following. Our outstanding feats were the unusual repertoire, the impressive drummer, a guitar player who played and sounded like the early Jeff Beck and sang like Steve Marriott, a second guitar player who sang like Phil May, and a bass player who could sing like Eric Burdon or Van Morrison. And we had: a) the ambition to play every song as close to the original as possible, and b) to play at least three new songs at every gig.

And, of course, the girls liked these handsome young guys…

Circle Line was a very short chapter. I joined them in ’67 to replace their unreliable conga player but soon found out they had absolutely no use for a conga player – their organ player wrote bombastic psychedelic songs that were each like a mini rock opera, with changes in tempo, groove, and style every sixteen bars. He then asked me to play bass, but that was no fun either, for the same reasons. I quit after maybe a dozen rehearsals.

In the same year, A Group II was an attempt to revive the first one, digging more into blues (Canned Heat’s ‘Refried Hockey Boogie’ in a 50-minute version, Cream’s ‘Spoonful’ in a 30-minute version…), but the new members didn’t really harmonize, especially not musically.

Action Set played blues rock and covered mainly Taste, Ten Years After, and Steamhammer material, but failed at trying to write their own songs.

I then moved to Amsterdam in the spring of ’69, trying to find a band there. I did find the musicians’ hangouts, but these guys all laughed at me: “Work in the summer? Hell, no, we’re all registered as out of work and get money from the government. Come back in autumn!” I slept on the living room floor of a friend and paid for rent and food by walking his German Shepherd dog for hours twice a day. But without any income, I couldn’t wait until the summer ended – back to Cologne again.

Enter Mhagara. Flute, guitar, bass, drums. Three vocal mics. Four guys and various girlfriends living in a four-room garden house – the fourth room was the rehearsal room. I slept on the hall floor or outside in the garden. We played a wild mixture of rock, blues, free jazz, and African and Latin rhythms we called free rock. One of the few things I’ll always regret is not having saved the recordings we made of our sessions – unfortunately, the flutist started to learn to play the saxophone and deleted all the recordings so he could record Charlie Parker and John Coltrane tunes and play them back in half-time to practice.

We really made fascinating music, and at the two gigs we had in the first year, we left the audience open-mouthed – and had only one more gig in the second year. No agent, no management, no band member who would sacrifice himself and try to acquire more concerts. We were broke all the time and would have starved to death without the women around. (And a lot of shoplifting…)

How did you get involved with Eiliff?

That third Mhagara gig was at a rock festival in Cologne. Being quite unknown, we played rather early in the afternoon. After the gig, Eiliff guitarist Houschäng Nejadepour came to me and said they were looking for a new bass player. He said he was fed up with the psychedelic kraut rock they were making and that my style would suit his new ideas much more. I had never heard of them before, and when they went on later, I understood what he meant – I didn’t like what they delivered either. But it was also clear that he was an outstanding guitar player, the keyboardist was fantastic, and the drummer was certainly a beast.

After their gig, we talked again and made a date for an audition.

I told my Mhagara mates about the offer and opportunity (Eiliff had two albums out and their label wanted more!), and they reacted sadly on one hand but encouraged me to give it a try – our own perspective was just too grim.

A week or two later, I jammed with Eiliff for about seven hours. It was as if we’d been playing together for years. Afterwards, we went to have a beer at their local village pub, and there too, we had a feeling of being on the same wavelength. Keyboardist Rainer Brüninghaus summed it up that night: “Perfect fit. That promises to become something special.” A couple of beers later, he announced that he was going to accept the offer of jazz guitarist and band leader Volker Kriegel to join his band Mild Maniac. What a loss.

But we were ready anyway, more than ever. And started to rehearse a couple of Houschäng’s compositions.

Further arguments for me were that they had rented a quite big house a little outside of the city, with a room for each of us, two bathrooms, a big kitchen, a garden, and a decent, fully equipped rehearsal room in the basement.

And they had gigs to come.

What was the energy like in that band?

A lot of laughter and merriment. A distinctive and honest devotion to music. And a strange sort of chaos. Houschäng was smoking illegal stuff around the clock, the sax player was a heavy drinker, and the drummer and I, after the afternoon rehearsals, would drive downtown almost every night, hanging around in pubs, looking for girls, and getting drunk. This made life rather expensive. Luckily, Houschäng was glad to hire me as his sub-dealer – so he could stay at home and play guitar and write new pieces, while I took his stuff to town, sold it there, and got a share of the income…

In the first year, 1972, we actually had a couple of gigs, maybe a dozen or so. We played clubs and festivals all over Germany, joined the German Jazz Union, and occasionally visited the Jazz Academy in Remscheid, where I had the opportunity and honor to meet, jam with, and learn from greats such as Volker Kriegel, Eberhard Weber, Gerd Dudek, Peter Brötzmann, Charly Mariano, Joe Nay, and the like.

Then Eiliff’s label, without naming a comprehensible reason, decided they weren’t interested in the band anymore and didn’t want to produce another album. That was a knockdown.

And it was an argument for the new keyboardist to quit.

While the sax player blamed it on the new musical style, confessing that he was fed up anyway with these Mahavishnu-inspired tunes in 7/8 or even 13/8 with ten-minute guitar solos and two sax solos per gig in which he regularly lost track. From then on, he only occasionally and listlessly showed up for rehearsals – the band slowly fell apart…

What led to Brainstorm?

In 1973, Houschäng got an offer from Mani Neumeier’s much more successful Guru Guru – and left. Drummer Landmann and I, for a while, tried to keep Eiliff alive – a new keyboardist, then another one, a new guitar player; for a couple of weeks, we even had a lineup with drums, bass, and three sax players playing tunes that I composed. But… no label, no management, no one there to tackle these problems – the patient was hardly breathing anymore.

So, by the end of that year, when an old mate from the ’60s, also a very good drummer, asked me if I was interested in playing bass in his band, he met with open ears. It turned out he played with Brainstorm, a four-piece jazz-rock band based in Baden-Baden in South-West Germany, almost 400 kilometers from Cologne. I took a train down there for an audition. It turned out they liked me and liked what I played, and I liked them. Great drummer, an excellent saxophone and guitar player (Roland Schaeffer), a functioning management, even a record deal – and they were in search of a new guitarist. I recommended another old acquaintance from Cologne, the young and extremely talented Nick Nikitakis, who gladly auditioned and was welcomed too.

With wives and kids, the Brainstorm lot had just moved into a beautiful mansion that included a rehearsal room in the basement, and sadly had no spare rooms left but organized a little under-the-roof flat in walking distance for Nick and me.

Same old story. Year one: Great new songs, successful gigs, even occasional work for the local radio and TV station Südwestfunk. Year two: Record label lost interest, management quit, too much hanging around – slow death.

Fun fact: Houschäng Nejadepour’s trip with Guru Guru lasted only one year and an album – a year later, Mani Neumeier made Roland Schaeffer an offer: Goodbye Brainstorm, goodbye beautiful Baden-Baden.

Back to Cologne for me. There, Detlev Landmann had opened a pub together with some Uli Hundt – they hired me as a barkeeper. After two decades of elaborate sitting on the other side of the counter, a job I was actually pretty suitable for…

Your journey through the 1970s seems like a whirlwind of musical experimentation and adventures. Looking back, what stands out to you as the most memorable or defining moment of that decade?

Uh… That decade was indeed full of outstanding adventures and experiences. Choosing defining moments is a hard one.

I’d start in 1968. Listening to a couple of albums for the first time: Van Morrison’s ‘Astral Weeks’ (with the overwhelming Richard Davis on bass! Before, I had spent a year playing along with Cream records and copying every note and riff Jack Bruce played until I believed I was Germany’s best rock bass player – but what Richard Davis did sent me back to restart…). Miles Davis’s ‘Bitches Brew.’ John Coltrane’s ‘Giant Steps’ and ‘My Favorite Things.’ Weather Report’s ‘I Sing the Body Electric.’ Joni Mitchell’s ‘For the Roses.’ The not only musical freedom I experienced with Mhagara. Learning the twisted Persian-Indian rhythms in Houschäng’s tunes. Hearing the first Mahavishnu album. Playing with so many great and different musicians, learning from each and every one of them. And getting compliments and encouragement from them (the great Steve Swallow tapping my shoulder approvingly!).

Finding out I was a pretty talented barkeeper. Talented enough, anyway, to never have to do one of those terrible jobs again that I had in the past to make a living and afford my musical ambitions.

Being on stage. Being capable of enthralling people, of touching them. Conjuring an expression of rapture on their faces. Making them dance and swing. Sending them off in a better mood than they were in before the concert.

And last but not least, the birth of my daughter.

What about Schroeder Roadshow?

But all that time there was a feeling, a notion, that all of this was only practicing, laying down groundwork for things to come. Just learning and widening my horizon.

I’m not sure that’s what I thought and how I saw things then, but in retrospect, it surely feels that way.

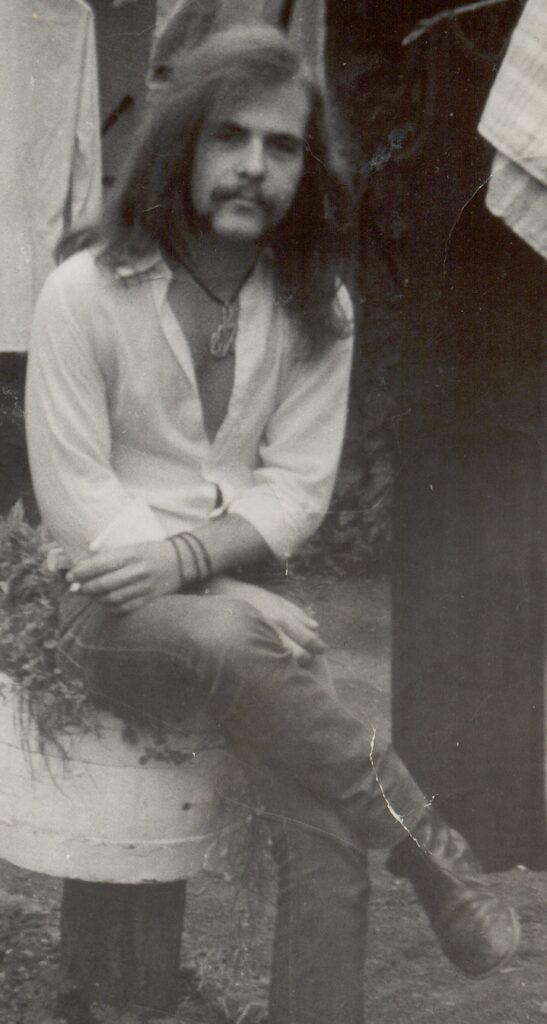

In 1975, in my spare time, I worked with a singer-songwriter who was convinced that the time had come to link up American-rooted folk, blues, and rock with German lyrics – Günter Hoffmann, R.I.P. He wrote the songs, I recruited Mhagara guitarist Gerty Beracz, a drummer, and a piano player, and took on the arranger’s role. We rehearsed for a couple of weeks and built a repertoire of songs that were… nice. But unfortunately, no more than that. It soon became clear that Hoffmann wasn’t really a team player. He left. The remaining four of us went on, played a handful of his songs, but weren’t too happy with it. So we started writing new songs ourselves, with me responsible for the lyrics (we stuck to the German language). We had two or three gigs, first as Hoffmann, then as Schroeder, with positive reception. But, being honest, the painful truth was our jazz-rock mixture with Beracz and me taking turns on vocals or singing harmony was enjoyably off mainstream – but not really something to make a crowd go wild.

Enter Uli Hundt. Yes, one of my bosses at the pub. I knew he wrote poems; he even had published a book with underground lyrics. But he told me he also wrote songs and was looking for musicians to help him arrange them and form a band to bring them on stage – did I have an idea?

I was willing to give it a chance. Hundt introduced us to a dozen songs, we worked out arrangements, and we knew this was a giant step forward in quality. His songs were sort of dirty rock, inspired by Zappa, Dylan, the Stones, and the Kinks, with harsh and funny, sarcastic, anarchic, and obscene lyrics artfully constructed. This, we were convinced, would be our breakthrough.

Still, there was something missing.

Then a girlfriend of mine told me I just had to come and accompany her to a concert. In a small art cinema, Jango Edwards & The Friends Roadshow played a series of seven nights. I went, watched, and lay under my seat with laughter and excitement. The next night, I took Hundt there. Same result. That was the missing link: Crazy costumes, make-up, anarchic stage show – a mixture of Zappa’s Mothers, Marx Brothers, and a hippie circus: one big YES!!!

We begged, borrowed, and stole the money needed, went to a little eight-track studio, recorded a self-produced (terribly sounding) album, and sent it to a couple of record labels. Two gigs in small Cologne clubs caused a stir. Trikont, a publishing company in Munich noted for their left-wing and anarchic publications, who also had a record label, told us they were enthusiastic about our album and eager to sign us. They booked us into an autonomous youth club in Munich, we drove the 600 kilometers down to Bavaria, rocked the club to pieces, and signed the record deal.

In Trikont’s office, HaGe Hein, a young man doing his alternative civilian service there, became our biggest fan and decided to throw all his occupational plans overboard and become our manager. A few weeks later, we toured Bavaria and did a dozen gigs in youth clubs and music pubs, sometimes for no more than twenty people. Who regularly freaked out and demanded three, four, five encores. And the press Hein managed to invite wrote hymns of praise everywhere. Fame spread, demand grew, and everybody wanted to book this refreshing new band.

No two months later, we did the same tour, this time playing not a dozen but two dozen gigs, not for twenty but for one or two hundred people each.

The Schroeder Roadshow was born.

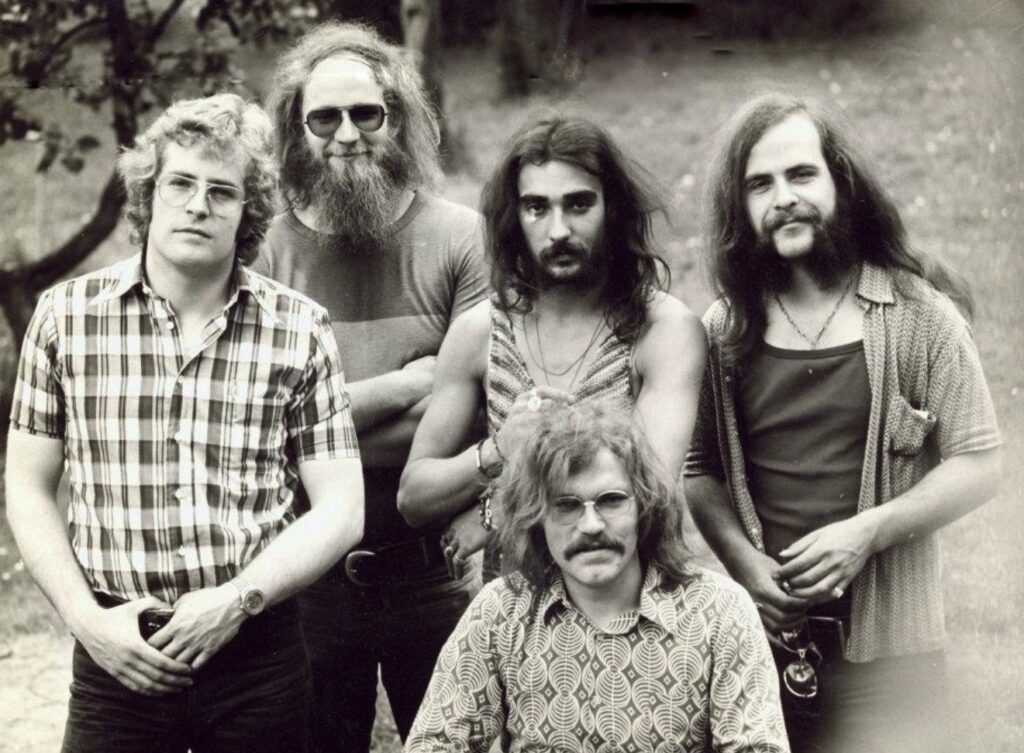

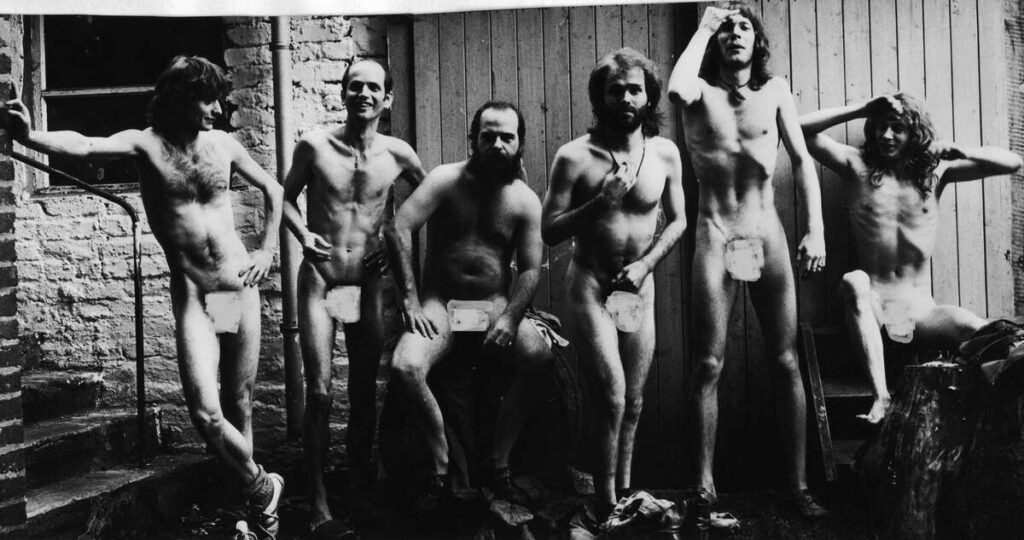

Uli Hundt (vocals, acoustic guitar), Richard Herten (drums), Gerty Beracz (guitar, vocals)

“We play everywhere where there’s a plug socket…”

Your involvement with Schroeder Roadshow seemed particularly impactful, especially with the creation of your own space for music and performance. How did this period shape your approach to music-making and collaboration?

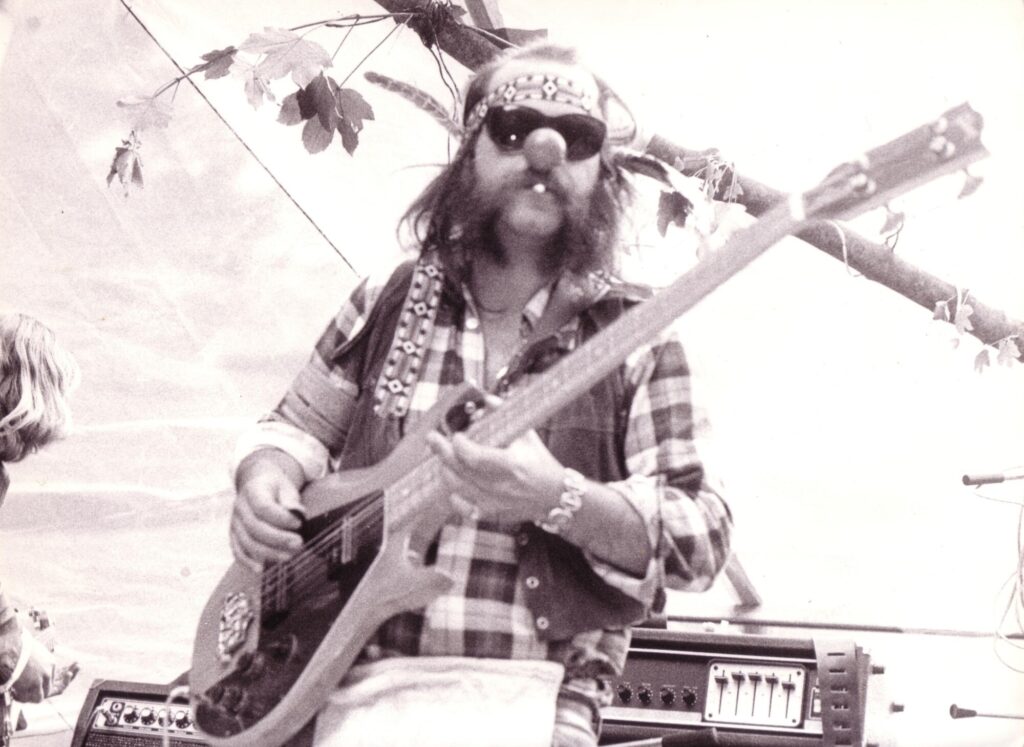

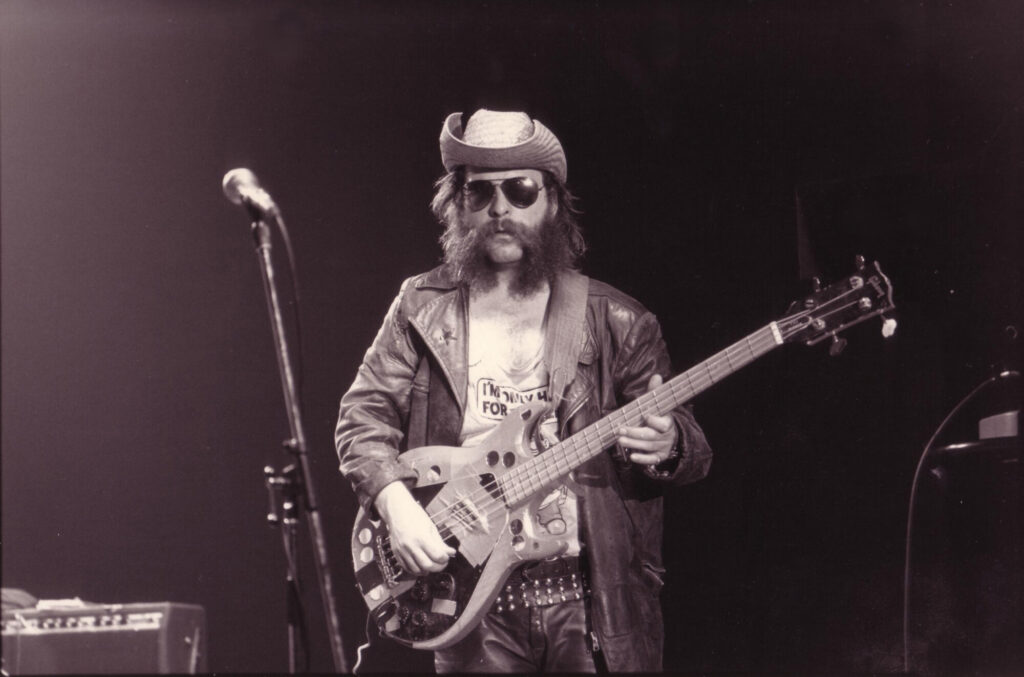

As mentioned above, we had found the missing link. The energetic package of dirty rock’n’roll, artful jazz-rock (we soon had a sax player), audacious parodies in various musical styles, both funny and hardcore political lyrics and announcements, and last but not least, an anarchic high-speed comedy show was something German audiences had never seen before. Every Schroeder gig was unpredictable—except for one aspect: The energy of their appearance had an unbeatable force that no one could elude.

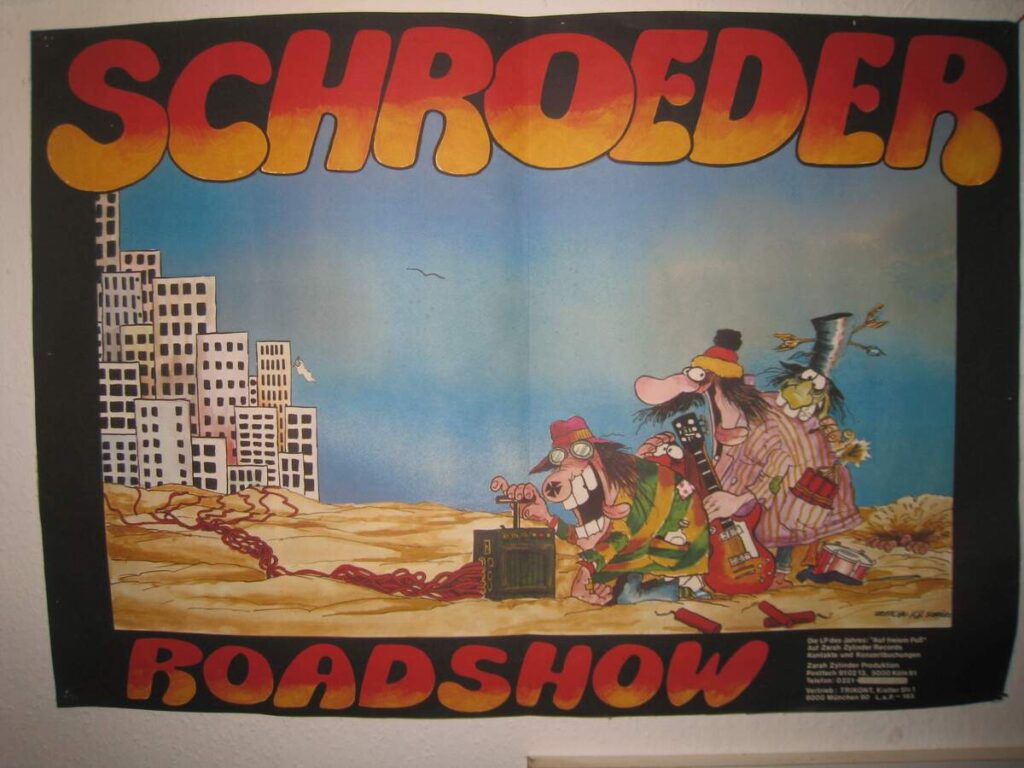

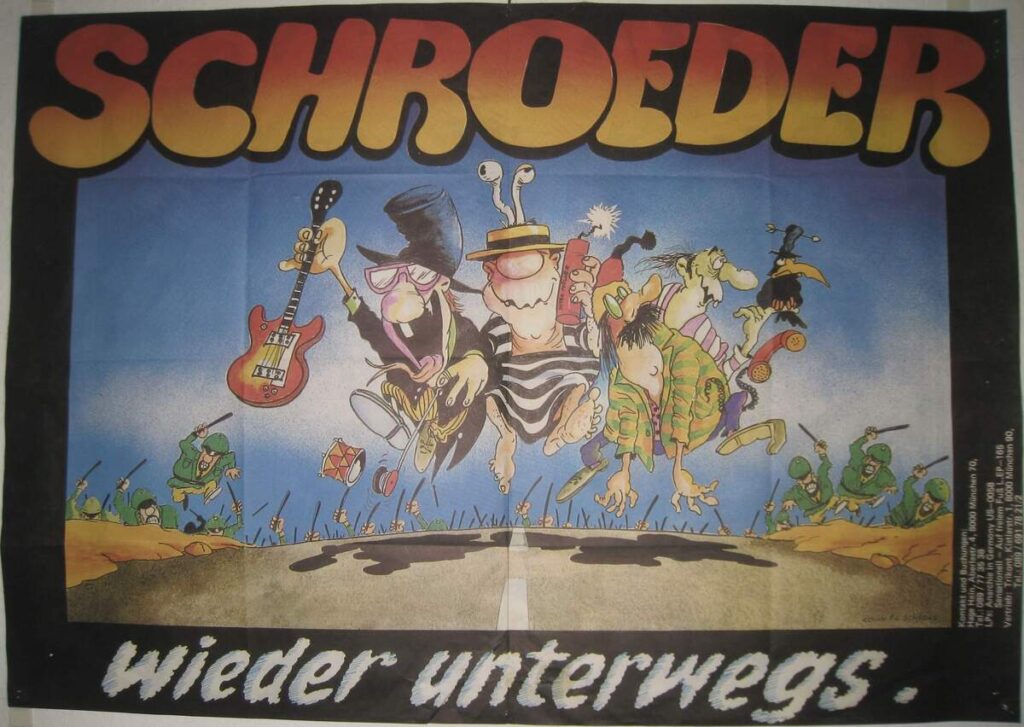

An aspect that definitely helped push our career was the tour posters created by cartoonist KH Schrörs. Very thick paper, great color print—and an unusual design. (And quite expensive.) Pretty often, regularly in fact, these posters would be plastered on walls and fences all across a town at night—and were gone the next morning to be hung in kitchens, halls, and bathrooms of the local flat shares…

Another aspect was our gig contract. Very important, besides the paragraph that demanded a case of cold beer for every band member, was the one that said: No hotels! We slept in private locations, mostly shared flats, often in sleeping bags on the floor, and, luckily, not infrequently in the beds of inclined fans. And of course, that meant partying around the clock—we opened our first beer during soundcheck in the afternoon, drank on stage where concerts usually lasted three hours, and then, after load-in, partied with fans and hosts until dawn. “Live like common people…”

Not to forget the zeitgeist—in ’77 we had what was called the German Herbst (German Autumn), a time when the RAF terrorists shook the country upside down, accompanied in left-wing circles by the famous “klammheimliche Freude” (clandestine joy), and on the part of the government, answered with massive oppression. Rarely was there a tour where our eye-catching tour bus full of long-haired freaks was not stopped by the police and threatened by pimple-faced young guys with machine guns in their trembling hands. And of course, there were our songs denunciating police brutality and the government’s politics and our statements on stage and in interviews—along with Ton Steine Scherben, we were the mouthpiece of the protesting German youth.

Besides, one of our rules was, “We play everywhere where there’s a plug socket…”

Gerd Köster’s entry into the band as a replacement vocalist brought a new dynamic. How did this change affect the band’s sound and direction, and what was it like working with him?

Köster was one of the regular customers of Landmann’s and Hundt’s pub and caught our attention for singing along with the Stones and Zappa records that used to play there, knowing every line by heart and hitting every note. He had a local little band with his soulmate Frank Hocker (who joined Schroeder in 1980). (Two years later, I produced an album with them, which, unfortunately, was soundwise butchered by the mastering engineer.)

For gigs in the Cologne area, we invited him on stage to perform Mick Jagger, Joe Cocker, or Tim Curry parodies. It became very clear that he had a convincing stage appearance—charisma.

A couple of days before a 1979 tour, Hundt suffered from serious kidney problems and had to cancel his participation. We asked Köster, who was then doing his alternative civilian service in a retirement home (and seeing his professional future there, too), to help us out and fill in. He pondered the idea for a day and then jumped. In three days and nights, he learned the tour setlist and said goodbye to his civic plans (and as far as I know, never regretted it).

Of course, there were some fans who missed Hundt, but Köster adapted very quickly to his new role, and within a few weeks, they were all fans of him, too. In the first year with him, every afternoon we worked on our program, collected jokes and punch lines, strolled through second-hand shops to buy funny clothes for ridiculous stage costumes, thought of new temporary roles for every band member, created bizarre choreographies, and trained the timing of fast dialogues and in-between gags. We played four times in a cabaret club in Munich, one week or even two in a row, every night sold out, and surprised the audience with a new setlist and new gags each night. And we had a really good time.

Album No. 2, ‘Anarchie In Germoney,’ became an underground hit.

Nothing lasts forever.

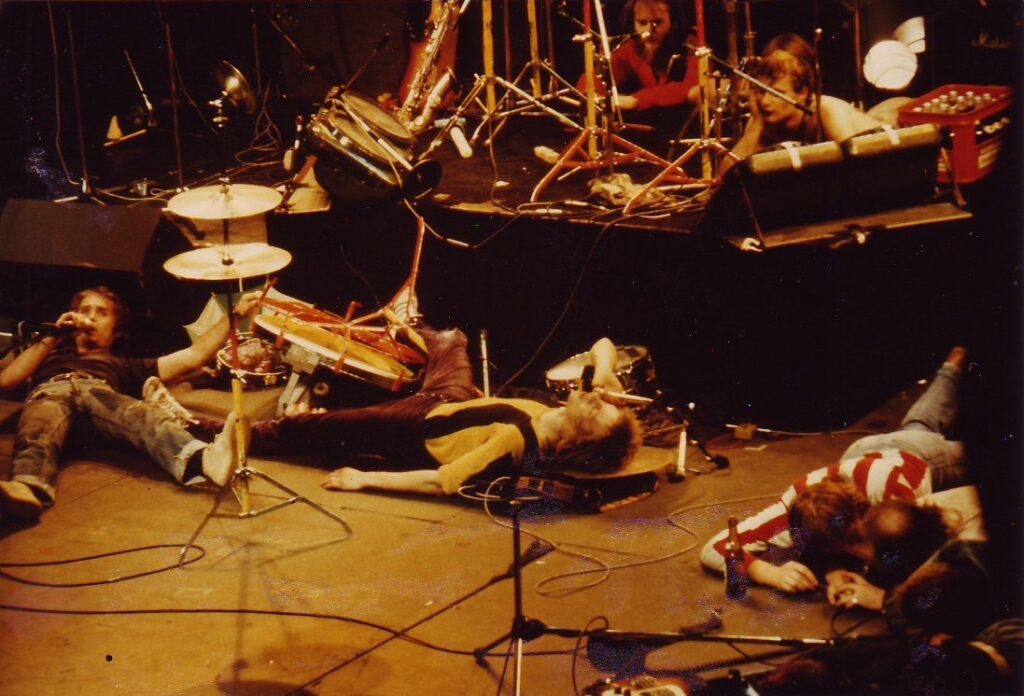

Excessive touring (more than 400 gigs in 1980/81 alone) and not less excessive after-show life demanded their tribute – the band was exhausted. About one third of the gigs were benefit concerts for autonomous youth clubs, political prisoners, or rallies against racism, sexism, or homophobia (yes, more than forty years ago!) – this drained energy and income. Having to play increasingly bigger venues meant we needed a bigger PA system; having that meant we needed roadies and a front of house and a monitor mixer; having that meant we needed a second tour truck. We worked hard 300 days a year (making three more albums in between) and came home to find out we couldn’t pay the rent there, except when the label paid us advances.

Another reason for the erosion was that each of us developed in different directions – one got fed up with the comedy aspect, another wanted more straight rock, the next one tended back to jazz rock, we all got fed up with the requests for benefit gigs, and we were all simply tired of clinging to each other around the clock.

An attempt to bail us out of this situation was signing a record deal with WEA in Hamburg in 1982 that brought us a huge advance payment and enabled us to book a real professional studio. Endless, tiring discussions about how the new album should sound led my colleagues to the decision that, after only four albums, I was not experienced enough as an arranger and producer – they insisted on calling in a second producer and chose Wolf Maahn. As a result, the album in the end – very much to my discontent – sounded like one of his albums, except for the vocals.

Which didn’t matter much – in the middle of the production, WEA boss Siggi Loch read the lyrics of the new songs, had a rage attack, and recalled the contract. And, of course, wanted their money back. We were very lucky to have some friends and fans at EMI in Cologne – they took over the contract and mercifully published the album.

And no one bought it. The bulk of our fans accused us of being traitors, having sold out to the evil commercial companies, and many even boycotted our concerts. On top of that, the German music scene and business had changed – the “Neue Deutsche Welle” (New German Wave) conquered the national music market and the charts and washed us against the cliffs.

In January 1983, we did a package tour with various acts like Udo Lindenberg, Konstantin Wecker, Ina Deter, Gianna Nannini, etc., to support the election campaign for the German Green Party (which turned out to be successful), and in the summer we toured for four weeks together with Ton Steine Scherben, jointly promoted by our manager Hein and the legendary Fritz Rau, but that was much less successful than expected, and after the tour, I quit.

The rest of the band canceled the “Roadshow” and continued as Schroeder for a year, with various line-ups but without the comedy show elements, even recording another album (with me as co-producer), which flopped too, and then they dissolved the band.

In 1988, there was a first revival gig at “Das Rennen” (The Race) in Hartenholm, in front of 200,000 people, and in 1992 a second one at the E-Werk, Cologne – and that was it.

The stage after the last encore looked like this, as usual:

Did you move to the United States in the mid-1980s?

Hm … This seems to be a case of misunderstanding: I (unfortunately?) have never been to the U.S. In case you are referring to my touring with Chicago blues singer Big Time Sarah – that was her tour across Germany …

In 2020, you embarked on several projects, including “The Tea” and “Here We Go.” Could you discuss the inspiration behind these projects and how they fit into your broader artistic journey?

Now this is really mysterious – neither of these titles says anything to me … Actually, in 2020, my old pal Gerty Beracz and I wrote a couple of songs in my home studio and produced an album under the moniker the little while. It was self-published in 2022. (Nobody bought it.)

What currently occupies your life?

Aging.

In 2022, I co-wrote a novel with another pal. We even found a publisher, and Folker hört die Signale came out in April 2023. In 2023, I worked on volume 5 of my Büb Klütsch series (vol. 1 published in 1992). At the moment, I’m waiting for feedback from my test readers, and I have now completed vol. 2 of the planned Folker series.

During the next couple of weeks, for a change, I’m going to have to generate some income and proofread a thriller by another author (because he was very satisfied with my work on the first one two years ago). When that (hopefully) is all on its way, it will be time to come back to music – this week a large update of my music production software (Logic Pro) came in, and it seems I’ll have a few new features to learn. Then I’m planning to a) produce and self-publish another mini-album of my music for unfilmed movies under the Caurey moniker, probably followed by work on the next Rich Choice song album.

I guess making more plans for the further future doesn’t make much sense – I’m not the youngest anymore, and life is full of surprising detours …

Thank you for taking your time. The last word is yours.

Well, thank you, first of all, for inviting me. It’s been fun to travel back in time and answer your questions.

My last word, as usual, is one of my life rules, borrowed from Willie Nelson – at least that’s what he said as an actor in the Michael Mann movie Thief from 1981:

“Don’t lie to anybody. If it’s someone you like, a lie can ruin everything. If it’s someone you don’t like – why lie …?”

Klemen Breznikar

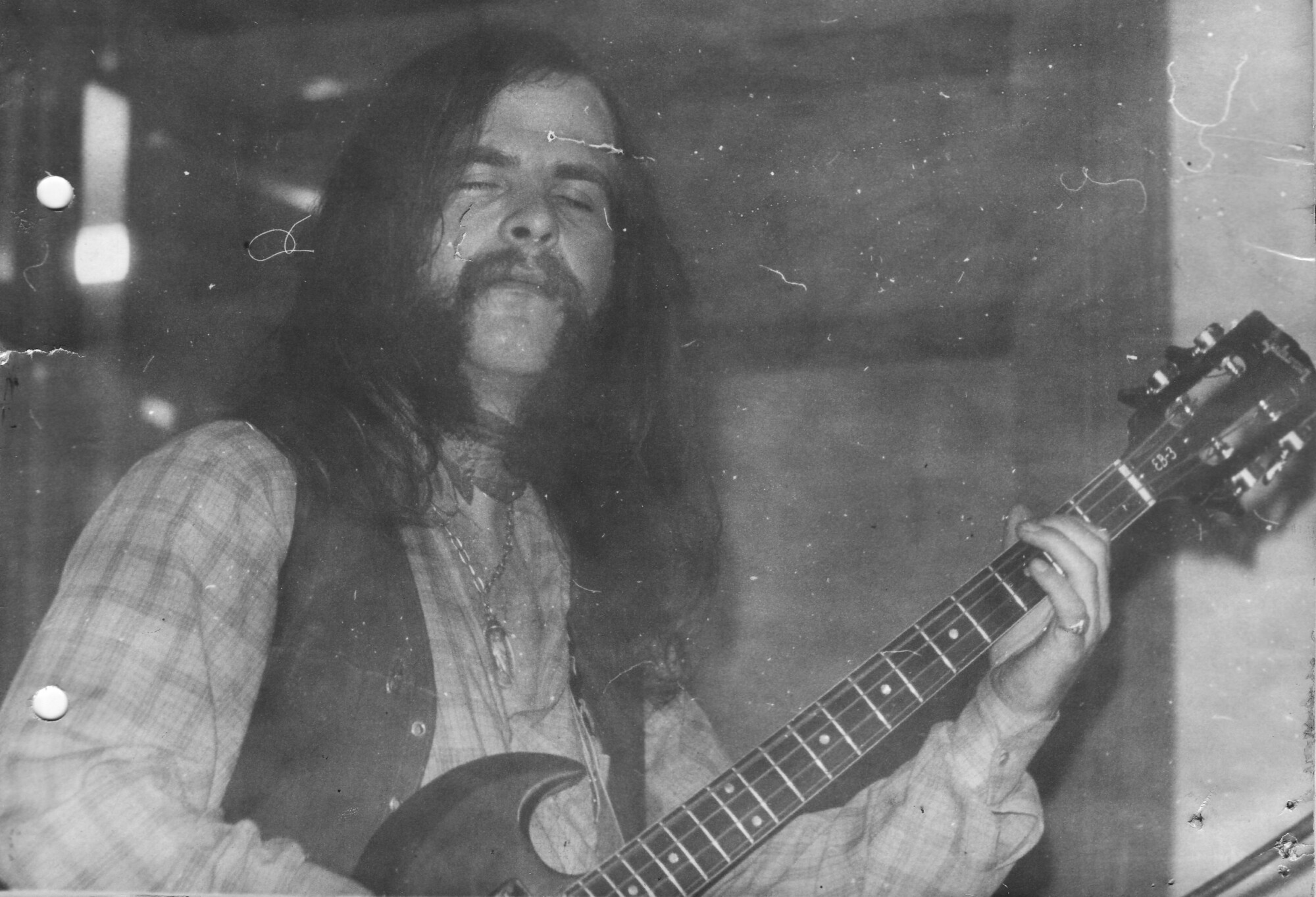

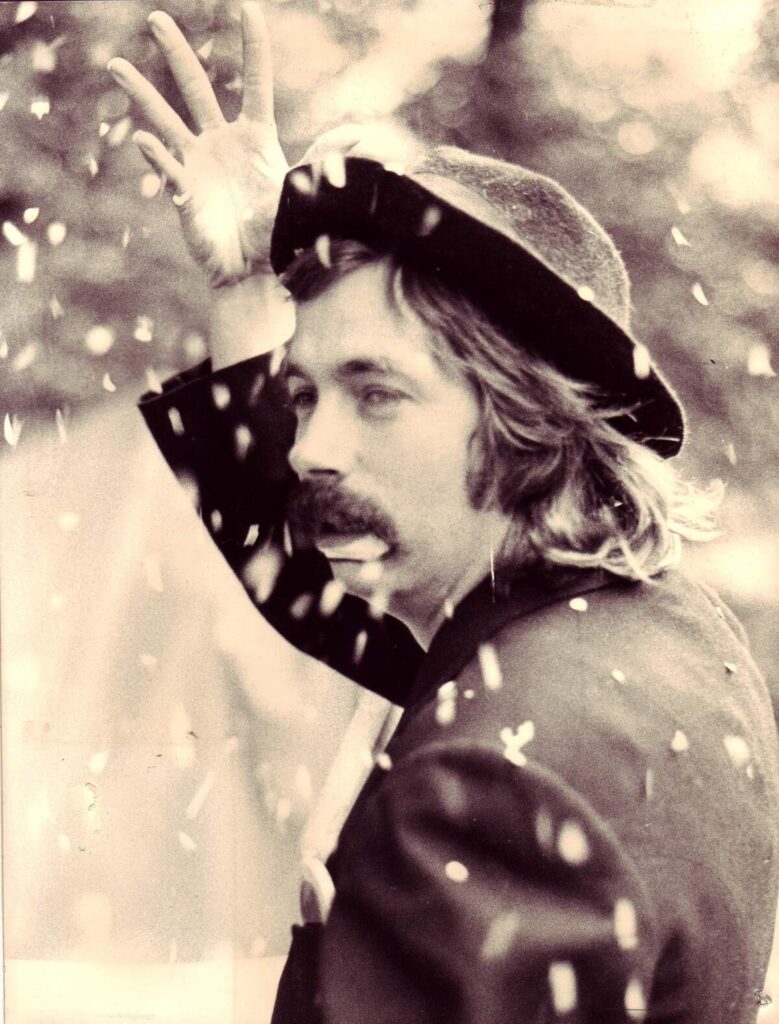

Headline photo: Rich Schwab (1972)

Rich Schwab Official Website / Facebook