Fire, King Earl Boogie Band, Strawbs interview with Dave Lambert

Hi Dave! I would like to thank you for agreeing to this interview. I love your work with Strawbs, King Earl Boogie Band and I am absolutely in love with your album called The Magic Shoemaker, released by Fire. Let’s start at the beginning. You were born Middlesex. What were some of your influences?

Thanks very much for the compliments Klemen, it’s a pleasure to do this. I was born in Hounslow, Middlesex, West London, about two miles from Heathrow Airport. When I was growing up there was always music playing in our house ranging from old time music hall to heavy classical. When my older sister could afford it, she started to buy the latest pop records. I very soon got hooked on The Everly Brothers, Buddy Holly, The Shadows, Tommy Steel, Chuck Berry and many others. My favourite, by a long way, was Eddie Cochran. I still think about his influence even today. In my opinion he invented what we now call ‘Rock’. Just listen to his track ‘Something Else’, it has all the hallmarks of modern Rock. Like most people at that time I heard Elvis Presley but, apart from the 56/57 recordings, I wasn’t too interested. I started to play ukulele when I was about six and moved on to guitar aged about seven. I’d been playing the drums since I could hold the sticks. Three of my uncles were drummers and they used to play with their knives and forks at the lunch table, I started to join in as soon as I could. The first stage performance I did was a solo spot during morning assembly at my primary school. I was eleven years old and I played and sang ‘Bring a Little Water Sylvie’ and ‘Worried Man Blues’. I got a double helping of pudding that lunchtime; the cook had heard me play and treated me to extras.

Were you in any bands back in the early 60s?

The first band I helped to form was a five-piece called The Hangmen. We were all 12/13 year olds at the same senior school, Isleworth Grammar School in West London. I was rhythm guitarist and we played a selection of Shadows tunes and some current pop songs. I wasn’t considered for the vocalist job because I was still singing soprano in the choir and that kind of voice wasn’t a lot of use to a pop band. We didn’t make any recordings with The Hangmen. I played an acoustic guitar with a pick-up in those days. I got my first electric guitar, a Vox Shadow, when I was thirteen. I straight away set about forming another band at school, I’d got bored with The Hangmen, they were a bit tame for my taste. This time I wanted to play in a three-piece and, along with a drummer and a bass player from school, I formed The Chains. The music was much rockier and blusier than I’d been playing with The Hangmen and I really started to get into it seriously at that point. We entered a national television band competition called Ready Steady Win and, to enter, we had to record an original song. I sat down and started to try to write something myself and that lead to my first two songs: ‘Bye Bye Blues’ and ‘Long Gone Baby’. We recorded them at a studio in Soho and I think we were all quite pleased with the result. I still have those recordings. We didn’t get very far in the competition but it didn’t matter too much because we’d got a lot of confidence in ourselves from the recordings. We played quite a few local shows with The Chains (we later changed the name to The Syndicate) and we stayed together for almost three years until we left school.

In 1966 you formed a band called Fire. It was consisted of you on vocals, keyboards and guitar, Dick Dufall on bass, vocals and Bob Voice on drums and vocals.

Although I was playing in a rock band during my teens I was also playing side-drum in a Boys’ Brigade band and in a Scottish bagpipe band called The Pride of Murray. It was a natural progression for me to follow my uncles into pipe-band drumming and I loved it.One Saturday night in 1966 I came home from playing with the pipe-band and I was pretty tired, all I really wanted to do was sit down in front of the TV. The ‘phone rang and it was my old friend Bob Voice. He said that he was round the corner in The White Bear pub. The pub was full, the entertainment (an accordion player) hadn’t turned up and they were desperate. Bob asked if I felt like coming round and playing a few songs, he said there was a drum-kit already there and he could tap along behind me. To be honest I wasn’t keen, mainly because I was tired but also I hadn’t played in front of an audience for over a year and I was out of practice. Bob finally persuaded me to give it a go and I’m so glad he did. We played for most of the night. I played and sang anything I could think of from Beatles tunes to heavy blues. We went down a storm and, while having a drink or two afterwards, we decided we had to form a band. I think we just got a bit carried away with the excitement of the evening. The next week we started to run through some tunes in Bob’s dad’s garage. I was keen to work in my favourite format; a three-piece. Shortly after, we were very lucky to get Dick Dufall to join us on bass. Dick also sang and so did Bob so we spent as much time on our vocal arrangements as we did on the music.

If I am not wrong you were also called Friday’s Chyld?

I still like the name Friday’s Chyld. It comes from a children’s poem about birthdays which begins: Monday’s child is fair of face, Tuesday’s child is full of grace…etc. When it gets to Friday it’s: Friday’s child is loving and giving. The spelling of Chyld was our own invention. The only reason we changed the name to Fire was because I felt Friday’s Chyld was a bit ‘soft’ and we were becoming quite a heavy and aggressive band.

In 1968 you released two singles. Father’s Name Is Dad/Treacle Toffee World, an amazing freakbeat number and Round the Gum Tree/Toothie Ruthie.

The songs and the recordings of Father’s Name Is Dad and Treacle Toffee World remain two of my favourites to this day. They were the first master tracks we recorded (we had made demo’s) and we made them at Decca studios in West Hampstead, London. We were very lucky to get Tony Clarke as our producer. I knew he liked our music and he was producing some great records with people like The Moody Blues so I trusted him completely. He produced those first two tracks for our audition with Decca which led to us being offered a contract with them. The strange thing was that Decca then refused to release Father’s Name as a single and that led to us recording many more tracks with Tony, trying to find the right one for a single release. None of us; the band, Tony Clarke and our managers, could understand why Decca wouldn’t release Father’s Name is Dad/Treacle Toffee world. One night Mike Berry from Apple Publishing, the Beatles’ company, came to see us play in South London. After the show he made it clear that he wanted to sign me to Apple Publishing as a songwriter and the following week I went up to Baker St and signed contracts. That was very exciting for a young band; to be signed with the Beatles’ organisation, we thought we’d made it there and then. Apple decided that Father’s Name is Dad should be our first single and they got straight in touch with Decca to tell them so. With Apple behind the record Decca finally agreed to release it in March 1968. Shortly after the record came out I got a call from Apple saying that Paul McCartney had heard the track, he loved the song and the riffs etc but thought the recording could be improved. The next day we were back in the studio with Tony Clarke. I sang a new lead vocal, Dick and Bob added extra harmonies and I added a high octave to the guitar riff. Tony made it clear he couldn’t see anything wrong with the original version but he worked hard with us to make the changes. The second version of the record was in the shops later the same week. It wasn’t until many years later that I started to appreciate how influential that record has been. I am aware of over twenty cover versions and there may well be more out there. I have heard from, and read about, a lot of musicians who cite Father’s Name as a major influence; that makes me feel about as proud as it’s possible to feel. Round the Gum Tree/Toothie Ruthie is a record I’d rather forget about. It was a huge mistake and I feel ashamed that I involved Fire in it. We were pressured to record those tracks and, on behalf of Fire and its integrity, I deeply regret it.

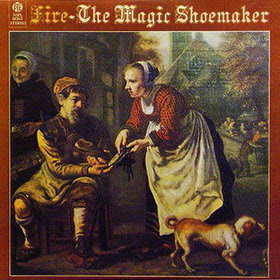

In 1970 you released a conceptual album.

For me, the interesting thing about The Magic Shoemaker project is that we were still quite young and relatively inexperienced as far as making albums was concerned, naive if you like. We had made a lot of single recordings at Decca with Tony Clarke, but the experience of recording a whole album was completely new to us. In 1969 I had decided to write a completely new stage act for Fire and I wanted it to be a series of character studies. I wrote a couple of pieces and then the song Magic Shoes, about a shoemaker, began to form. Originally it was going to be a one-off piece. Slowly, as the idea of the lyric developed, I realised I was thinking along the lines of a complete story, a fairy story. For the next six weeks or so I wrote day and night trying to come up with new songs that would tell the story of the shoemaker and his magic shoes. I can’t pretend that I was trying to do anything ‘proggy’ I simply wrote the tunes and lyrics that came into my head; it was only when Fire started to rehearse the songs that I realised I was changing our style.

Album was released by Pye. What are some of the strongest memories from recording it?

We recorded The Magic Shoemaker at Pye studios in Bryanston Street in the West End. As I said before; we’d never recorded an album before so I think we were unprepared for the intense workload that it entailed. All of the sessions were late-night and for a couple of weeks I barely saw daylight because I slept until it was time to return to the studio that night. Everything went quite smoothly during the recordings and, for the most part, it was a very enjoyable experience. I asked Paul Brett to play guitar on some of the tracks, mainly to take a bit of the workload off of me; I was writing, singing playing guitar and keyboards and sometimes percussion, so I needed someone to help me out. Dave Cousins came in and played banjo on one of the tracks too. The only worry I had was whether or not the whole idea would work and that would only become clear when it was all finished. I can’t honestly say that I set out to write and record a fairytale concept album, the idea simply evolved and presented itself to me. I think that’s true for most artists; you start with an idea and, by the time you have the finished result, you arrive up miles away from your original idea having gone on a journey through your conscious and semi-conscious thoughts and experiences. It can feel almost supernatural it’s as if something or someone has taken over during the writing process.

How many copies were pressed and what can you tell us about the cover artwork?

I can’t remember the name of the painting, or the artist, which features on the front cover of the album; I just remember it was Dutch. Ray Hammond, one of the album’s producers, saw the painting and thought it was perfect for our album. He acquired the necessary permission and it became, in my opinion, the perfect image for the project. I have no idea how many copies of The Magic Shoemaker were produced or sold. I’ve always assume it wasn’t many simply because it is such a valuable record in the collectors’ market. It’s been available on CD for a few years now and what I find amazing is; how popular it is around the world, especially in Asia.

Did you perform Shoemaker at the time?

We didn’t perform Shoemaker at the time; I had to wait until 2007 for that experience.

Fire disbanded in 1970.

As I said earlier; the recording of the album was extremely hard work for me and it finally took its toll. My exhaustion combined with the fact that the album didn’t chart left me wanting to quit. I felt I could do no more for the band, I had tried my best, we all had, but the time had come to call it a day. We’d had four very happy and educational years together but we’d gone as far as we could with the line-up. Bob and Dick went with Paul Brett to form Paul Brett Sage. I tried to form a new Fire but it didn’t work out, I don’t think my heart was really in it. I decided to write some new material that I could perform as a solo act and set about working the folk-clubs.

Then you joined the Strawbs.

One night in 1969 we were supposed to be rehearsing with Fire but, because of a mix-up, the rehearsal was cancelled and we went for a drink to a local folk-club. The band that was on was the Strawbs, having recently changed their name from The Strawberry Hill Boys. I got talking to Dave Cousins afterwards and it turned out that he lived a couple of hundred metres from my house. We soon became friends and began to write a few things together. He and I did some shows together in folk-clubs during the following couple of years. Eventually, when they were trying to turn Strawbs into more of a rock band for the US market, I was asked if I’d like to join, and I happily accepted. I had just finished playing on Dave’s first solo album and it all felt very natural to be working together in Strawbs.

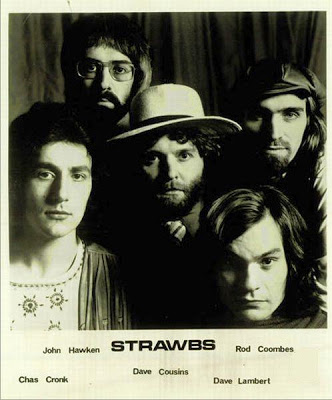

You were in the Strawbs from 1972 until 1978.

I joined the band in the summer of 1972 and I left at the end of 1978. We had our first hit single, Lay Down, just after I joined that was followed by the big hit Part of The Union and then the album Bursting at The Seams which was also a huge success. In the autumn of 1973, for various reasons, the band changed line-up. Dave Cousins and I put together a new Strawbs and we designed it to be suitable for playing the US stadium shows that we were doing more and more of. That line-up with Chas Cronk on bass, Rod Coombes on drums and John Hawken on keyboards, recorded the albums Hero and Heroine and Ghosts which were to become our signature albums in America and Canada. After John Hawken was replaced by John Mealing and Robert Kirby, we went on to record Nomadness, Deep Cuts, Burning for You and Deadlines. I left the band after Deadlines. There are far too many great memories for me to be able to pick out just one.

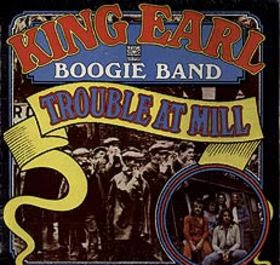

You were involved in another project called King Earl Boogie Band.

During the period after Fire when I was playing solo, I was invited to join a Mungo Jerry UK tour. I was given a solo spot and I did the introductions for the show too. Sadly it was to be the last tour that the original Mungo Jerry line-up did. The band was splitting away from singer Ray Dorset during the tour and I was asked if I’d like to form a band with the remaining members. We formed The King Earl Boogie Band and recorded a single, Plastic Jesus, an album, Trouble at ‘Mill, and a second single, Starlight. Almost immediately after the second single I was asked to join Strawbs and, as sad as I was to let the King Earl guys down, I knew I’d made the right decision.

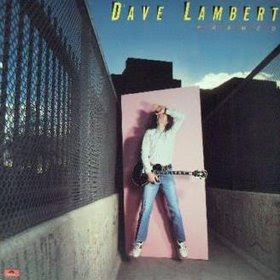

In 1978 you released solo album Framed.

I left Strawbs late in 1978 and almost straight away I was preparing for the recording of my first solo album. The album, Framed, was made in Los Angeles and it was a fantastic experience. I had Richard Bennett on guitar and Tom Hensley on keyboards, both from the Neil Diamond band. Denny Sewell, who’d recently left Wings was on drums and, for most of the tracks, John Entwistle played bass (Leland Sklar played bass on the tracks when John wasn’t available). John and I had been friends since 1960 but this was the first time I’d had the chance to play with him. The whole band was so easy to work with, they were keen and, obviously, bloody good. I still like the album very much but I don’t think any artist is ever entirely satisfied with their work, that’s the reason we keep going; striving to make that ‘ideal’ piece.

What followed?

After Framed I decided I wanted to get out of the business, at least for a while. The punk thing was happening and I didn’t really feel I belonged anymore. I didn’t particularly like what was going on; it seemed to me that there were a lot of people getting away with rubbish. There was some good stuff around but there were a lot of talentless people jumping on the bandwagon. When the punk thing first started I got quite excited about it, I thought the old barriers would be broken down and something new and different would rise from the ashes. It didn’t. So I decided to leave the business that I loved, believing that it no longer existed. I started to teach guitar more, something I’d always enjoyed doing, and then I trained as a ski instructor with the Austrian ski-school. After I qualified I spent twelve seasons in Niederau in the Tyrol and had a ball. I was teaching skiing for four hours during the day and, three nights a week, playing solo at a bar in the village. Life had become quite idyllic and, I thought, I was in semi-retirement.

You rejoined with The Strawbs around 2000?

It was actually 1998 that I started to play with Strawbs again. I got a ‘phone call from the band and they told me they were putting together a concert to celebrate the 30 year anniversary of Strawbs. They asked if I’d like to be involved and, after a bit of deliberation, I agreed. The concert went very well and the decision was made, by all of us, that it would be a good idea to re-form and start touring again. We’ve been touring strongly ever since. Until the anniversary concert I sincerely didn’t think that I missed playing on the road, but as soon as we got on stage I knew it was where I wanted to be, and to continue doing it for as long as I could.

In 2008 there was Fire reunion.

At the end of 2006 we had a Christmas meal together; Dick Dufall, Bob Voice, Ray Hammond (the producer of The Magic Shoemaker) and me. I had been thinking about staging The Shoemaker album in its entirety for a couple of months but I didn’t think the other guys, because of their own commitments, would be able to do it, also I knew that Bob hadn’t played drums for many years. So, I announced over dinner that I was planning to stage the show. Straight away they all said that they wanted to be involved which quite surprised me, but I was delighted and excited to know that the original Fire would, at last, play The Magic Shoemaker on stage with Ray Hammond doing the narration of the story. We agreed that I would book a theatre for the following year and we pencilled November the 30th and December the 1st 2007 into our diaries. I went home on the train that night with a thousand thoughts going through my head. All through Christmas 2006 I was in my studio writing and recording a new overture for the show and the next couple of months I spent writing a script for Ray, lighting and sound scripts, running orders, press releases etc. I loved every minute of it, I was still very excited. Fire started rehearsing in March and we had regular rehearsals throughout the year. Both of the shows went like clockwork and all the preparation paid off. Paul Smith, Strawbs sound engineer, did the sound for the shows and he recorded both nights. The album, The Magic Shoemaker Live was released in 2008 on Angel Air Records. I think all of us enjoyed the experience enormously; I certainly wouldn’t have missed it for the world.

What are some future plans?

Strawbs continues to tour in two formats. Apart from the full electric line-up we now have Acoustic Strawbs which is Dave Cousins. Chas Cronk, and myself. Both the electric and the acoustic bands tour regularly and I hope that will continue for some time yet. We try to release a new album every 18 months or so and we have a new one, Hero and Heroine In Ascencia due out in the next couple of months.

Thank you for taking your time. Last word is yours.

Thanks Klemen. All the best to you and please pass on my best wishes to your readers. People can find out more about the history of these bands from the various web-sites. www.strawbsweb.co.uk www.myspace.com/davelambert07 www.myspace.com/2007fire and I can also be found on Facebook.

– Klemen Breznikar

Array