Chris Cutler interview about Henry Cow, Art Bears, Cassiber…

Thank you very much for taking your time. You’ve been part of so many amazing projects. Where did you grow up and what were some of the influences?

I was born in Washington DC but moved to England when I was about two. So I grew up on the outskirts of London. Musical influences were, I suppose, listening to radio Luxembourg on a crystal set when I was supposed to be asleep, skiffle, New Orleans jazz, The Shadows, messing about with a tape recorder, playing records at the wrong speed, learning banjo and trumpet, then guitar – wanting to be in a band and taking up drums – well a snare, bass drum and one cymbal – because everyone else played guitar as well, better than me. Then the Yardbirds; the Who; Stockhausen; Frank Zappa; AMM; Sun Ra…

What bands were you part of?

A string of bands. That was when you played in pubs, hospitals and church halls so that people could dance; concerts for rock bands didn’t exist then, so we all had a vast repertoire of songs – because you had to play what people asked you for. In the Copper Coins it was guitar instrumentals until, like our peers we shifted to R&B. In The College Boys it was pop and R&B. We played at debutante’s parties, bars and yacht clubs. We had a manager who wanted to be Brian Epstein and sent us long critiques and sartorial suggestions in brown or blue type every week. Then came the Wine Merchants, a serious soul band with burgundy waistcoats and a nifty brass section. We played at Mecca ballrooms mostly and we had a seriously talented guitarist. He did all the arrangements too. I’m sure he made a career. Then there was a duo with a guitarist that played three nights a week at the Three Feathers in Ealing; that was pop in the early evening and Irish revolutionary songs before closing time (it was a hardcore republican pub). But it was Louise that lasted longest and made the transition from R ‘n B and early electric Dylan to full-on psychedelia. In fact the music got so strange we couldn’t get gigs any more because no one could dance to it. And we wrote our own songs, which was bad, but worse was the fact that we improvised with noise. It was late 1966 – and soon other, similar, groups started to surface around us (Barratt’s Pink Floyd, Soft Machine &c), and we were able to start playing again in the London clubs – and now to audiences that listened as well as danced; and who expected to hear music that was new and different. But that was in London… we still couldn’t play anywhere else.

Around 1971 you joined Henry Cow.

After Louise I was looking for something at least as interesting, so I put an advertisement in the Melody Maker. A rather odd advertisement designed to deter commercial bands from getting in touch. It put me in contact with a lot of interesting people, who were also looking for something….. but no bands. In 1971, Dave Stewart and I put The Ottawa Music Company together with some of those people – that was a 22-piece rock composer’s orchestra and something of a project before its time. Then Henry Cow got in touch. We rehearsed. Did some gigs together, and after a while I joined permanently (and they also joined the Ottawa Company).

What are some of the strongest memories from recording “Leg End”?

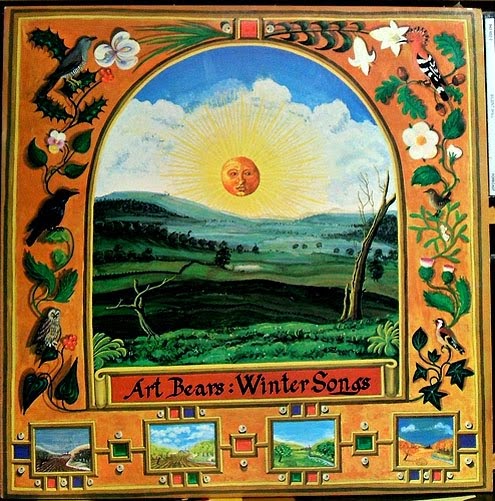

Being in the studio and learning what it could do. We were extremely lucky with our engineer – Tom Newman. He taught us how to do things for ourselves at a time when technicians wouldn’t normally let a band anywhere near a mixing desk. It took us about a month to make Leg End, which is quite long (Art Bears’ Winter Songs only took a week) though the time shot by and we still weren’t happy. The Manor (Virgin’s studio and Branson’s home) was just starting up then and was still like a big… household: staff and bands ate together and socialised together. It was very relaxed. Henry Cow came in just as Magma was leaving – and to save money Virgin recorded Leg End over the top of the multi-track master for Mekanihk Kommandoh Destruktiw – something they would later regret.

Later you recorded “Unrest” and “In Praise of Learning”. Would you like to share a few memories from that period of time?

Unrest was a giant stress. We hadn’t got enough new material for a second album. Lindsay had just joined and she had to have two wisdom teeth taken out before the session, so playing was still painful for her. We gambled on being able to use the studio to compose with; and we made the whole of side two from nothing, starting with improvisations and then writing, overdubbing, editing and manipulating the tape until we had produced seven finished, quite complex, pieces. Phil Beque engineered that album. He was incredibly patient; we had to learn everything as we went along. But it worked. At least we thought so. We were so pleased that we invited the whole Virgin Portobello office team to come to a collective listening. But they didn’t share our enthusiasm. They seemed mostly – nonplussed, which was – to say the least – depressing. In Praise of Learning, our second collaboration with Slapp Happy was different. We’d got the hang of things by then. And we knew what we wanted to record. But it still wasn’t what Virgin wanted, and that was the last record we did for them.

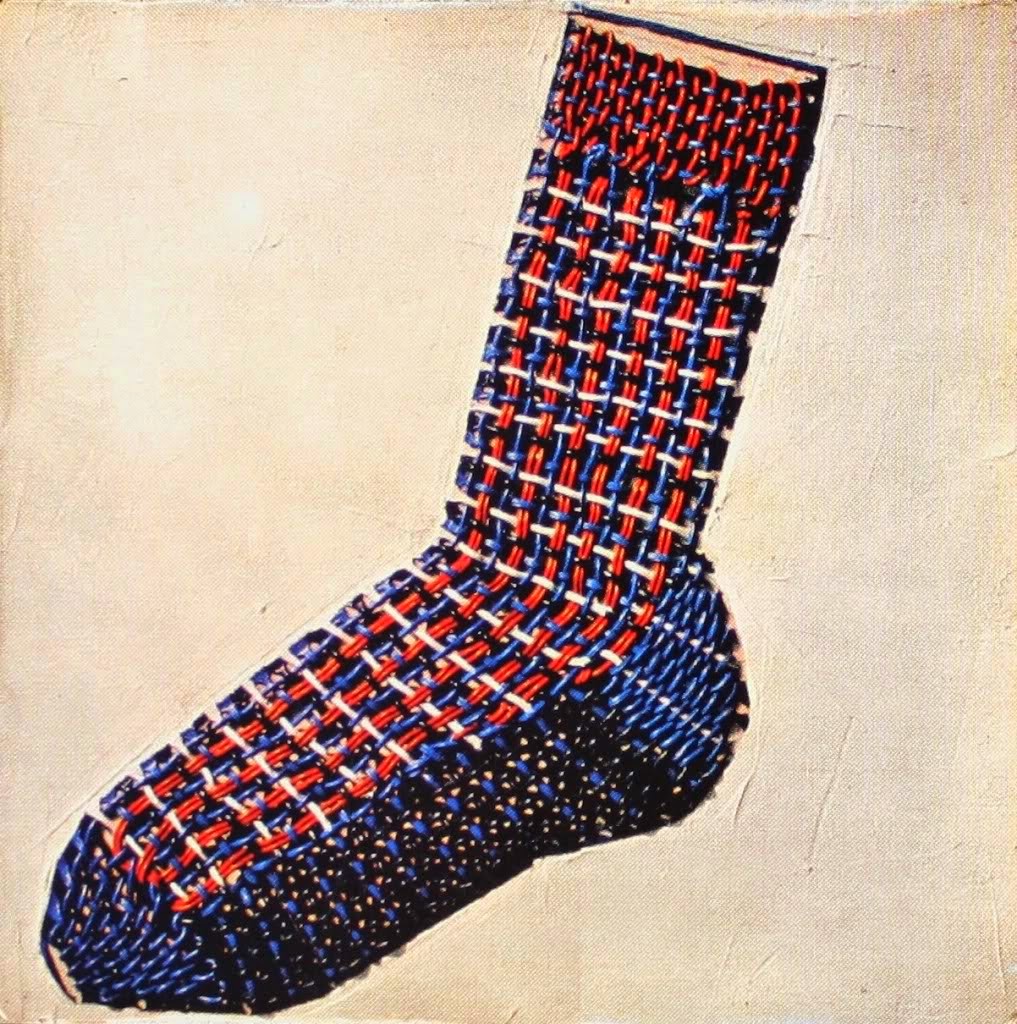

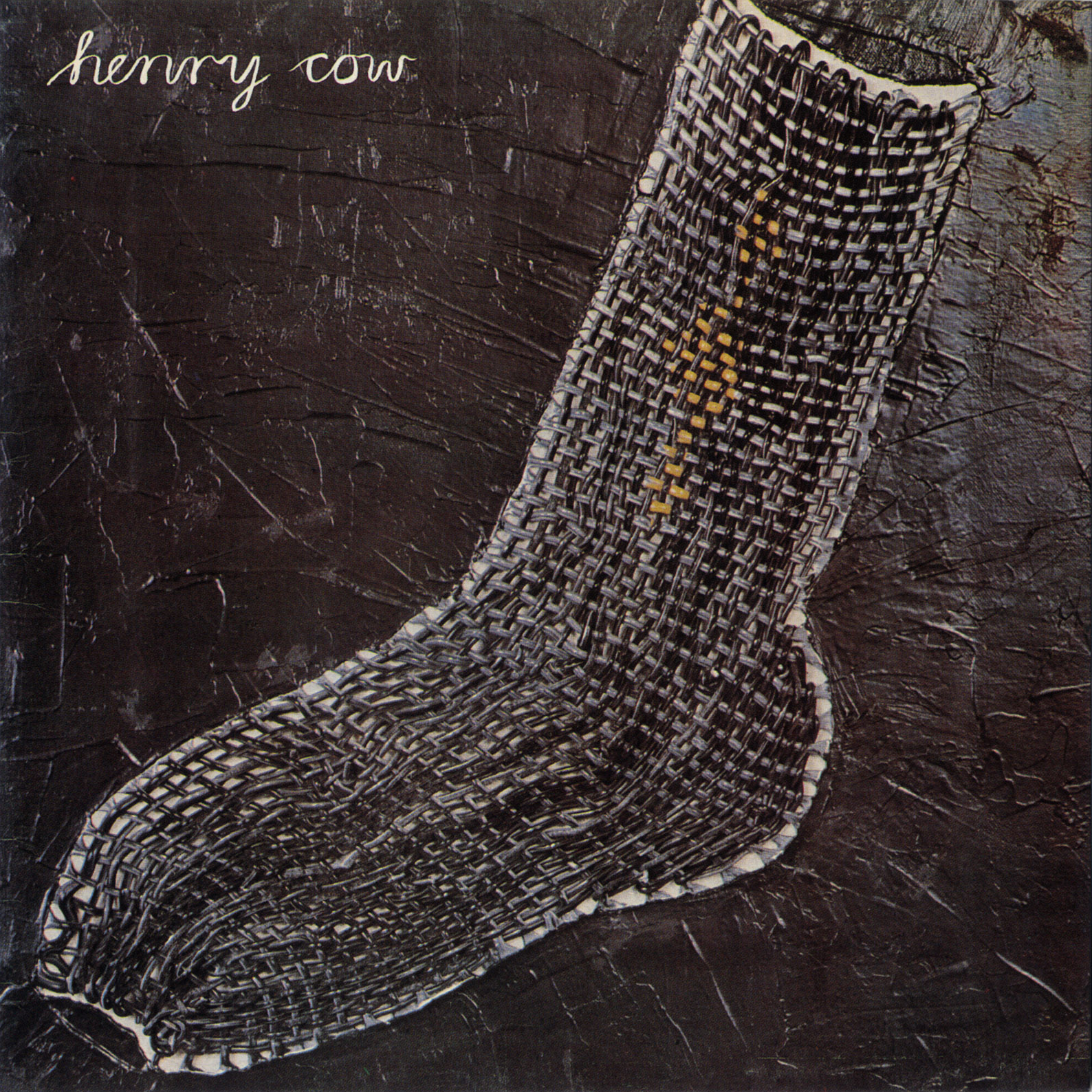

How did you choose the name “Henry Cow” and what can you say about your cover artwork?

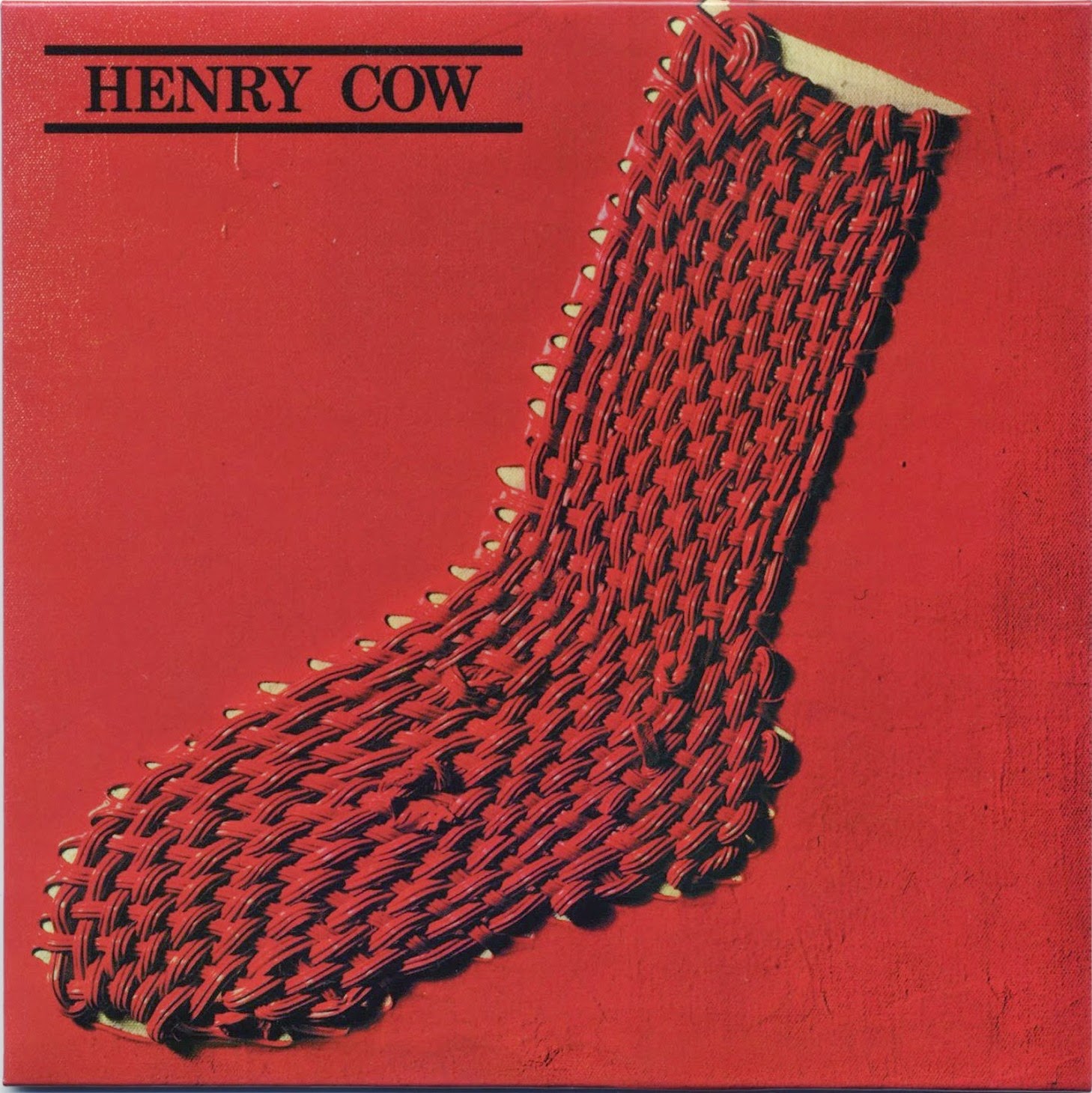

The name and its origins are shrouded in mystery. No one can remember now. But it was our name and it stayed. The artwork for all three LPs was done by Ray Smith, an old friend from Cambridge, who had worked with us on two dance projects and who often joined us – doing what would now be called performance art (ironing, setting up a tent &c.) – at concerts. He came up with the woven sock and insisted there be no band name on the front cover, and followed that idea through the whole series, just changing the socks to suit the temper of the music.

Your last album was released in 1979 and after that you started your own record label )”Recommended Records”) with Nick Hobbs and you also formed “Art Bears”. What can you say about that period of time?

It was insanely busy. After recording the first Art Bears LP – which started out as a Henry Cow LP until the band decided not to release it, we decided to stop Henry Cow – but tour for another 8 months, to say goodbye to all the people who’d supported us over the years. Breaking up was a bit like being born again. We wrote a whole new programme of music, merged with the Mike Westbrook Brass Band, co-organised Music for Socialism, set up Rock in Opposition and ran a festival in London. In the middle which I also set up Re Records to release the first Art Bears CD (adding 4 extra songs that Fred and I had to write in order to complete it) and Nick Hobbs (H Cow’s administrator) and I set up Recommended Records at the same time, as a mailorder and distribution network. We also toured Europe, did a Paris residency with the Art Ensemble of Chicago and made another LP. It was a busy six months.

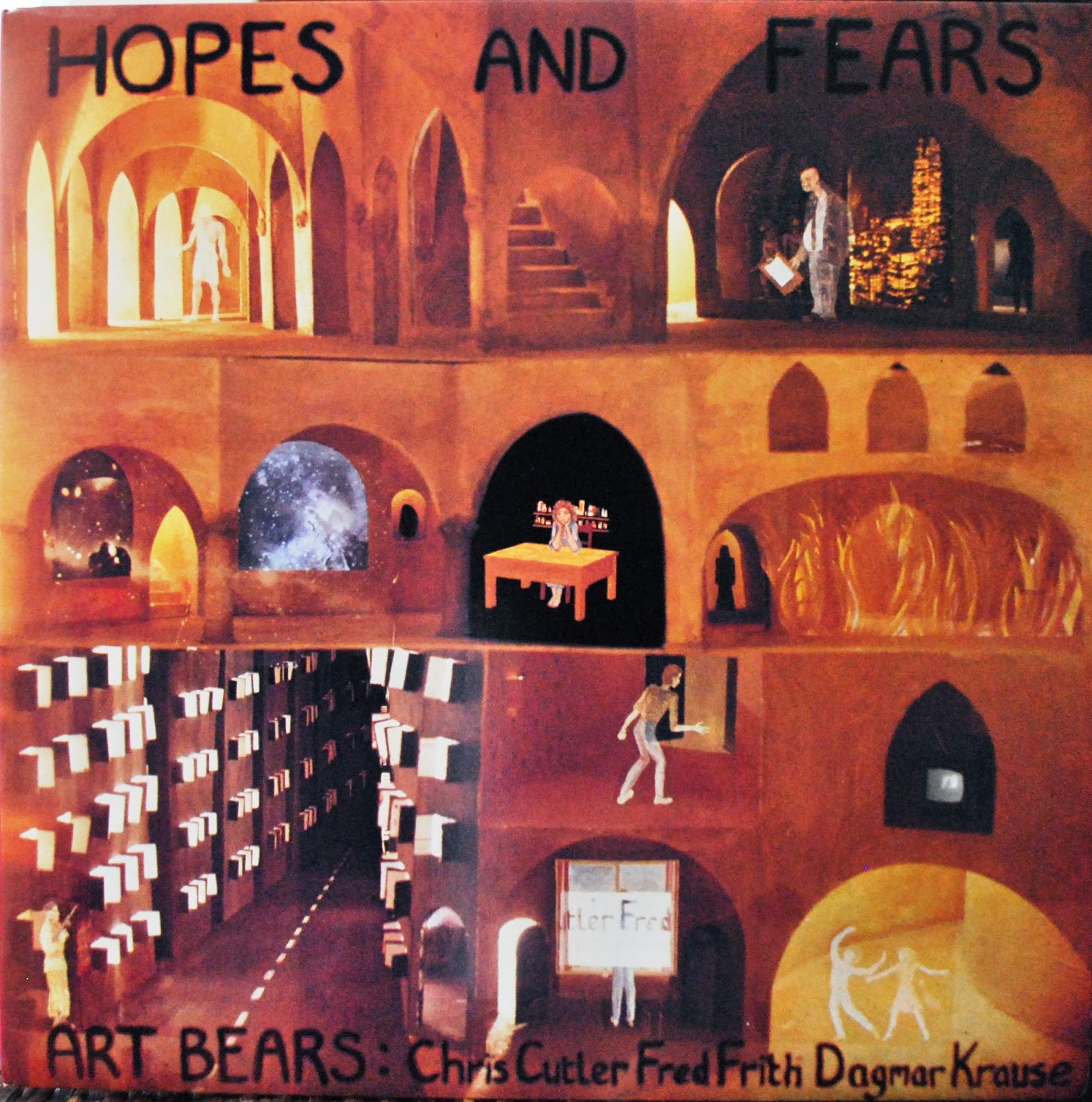

“Art Bears” released three great albums. How do you remember recording those albums and what is in your opinion the main difference between “Art Bears” and “Henry Cow”?

For the first, none at all. It was recorded (except for the 4 extra tracks) by Henry Cow, as Henry Cow. But those 4 tracks did become the key to the new project. For them, Fred and I adopted a completely new work method, based on what we had learned not to do in HC. We wrote fast. We never rehearsed or tried to play the songs. We’d just meet in the studio, put down a click track and a vocal guide, add some structural musical scaffolding and then get the voice on as early as possible, along with whatever specific elements Fred had written (often quite a few). After that we built the track up, part by part. The first rule was to do as little as possible to each song, and not to discuss it first. The second was that all the sounds would be designed before parts were invented for them, and the final performance would be put straight to tape – so we didn’t leave getting the sound right to the mixing stage.

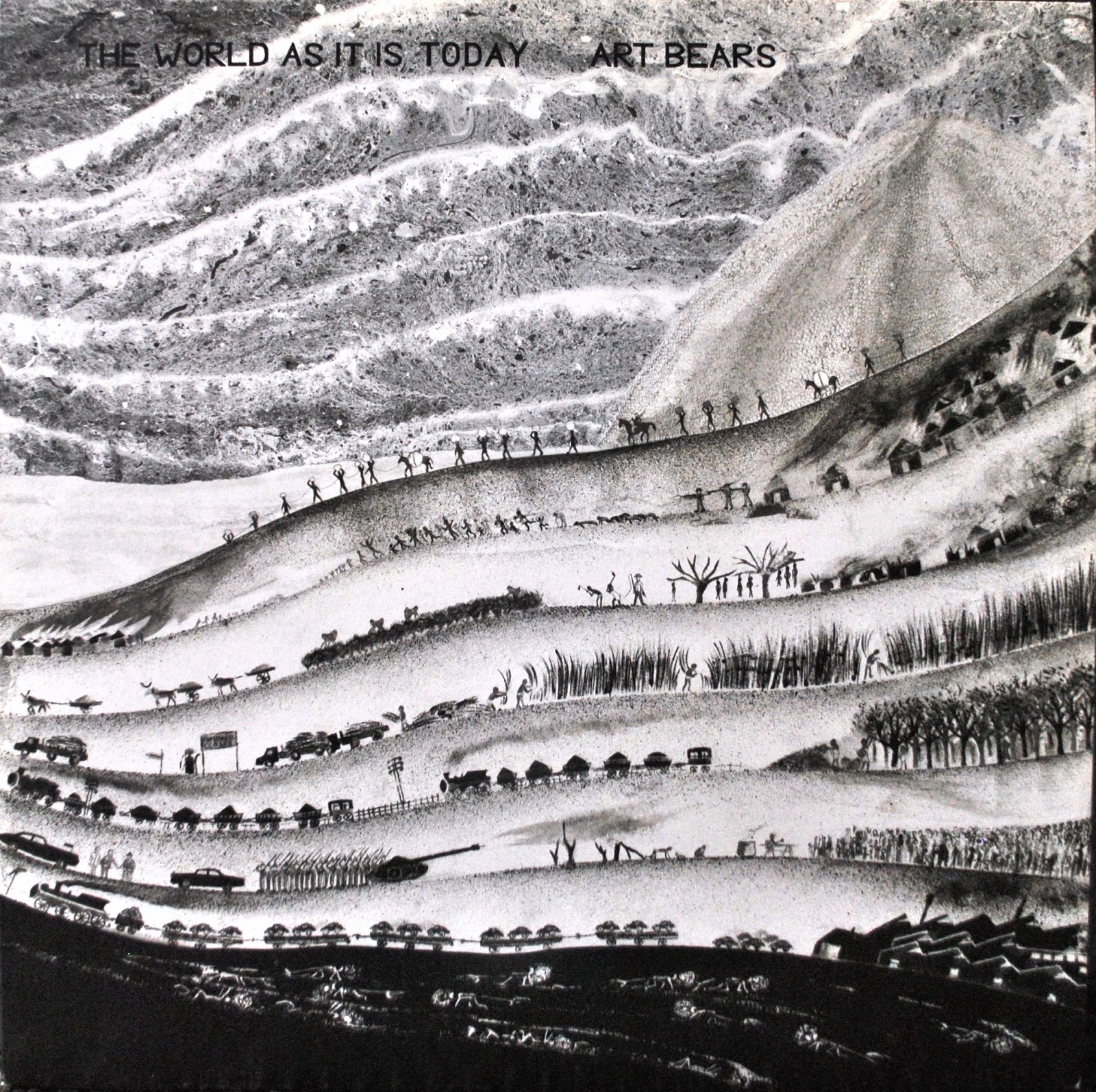

Making Winter Songs was an incredibly intense experience because once we’d jettisoned the conventional rules of recording practice, we had to invent a whole set of new techniques to achieve what we wanted. In large part that was thanks to the imagination and flexibility of Etienne Conod, the studio’s owner and engineer. But it was exhilarating. I hardly ever left the recording space (I slept under the piano at night) and we worked non-stop. The whole album was written, recorded and mixed in a single breath – well, in one joined-up week. Our next, The World as it is Today was also intense (so much so I hit the road hitching instead of going home when we finished it) but the group was hanging by a thread by then, and our individual lives had moved in different directions. Still, I’m glad we got it down; for me it perfectly summed the existential condition of its time.

You recorded with “The Residents”, “Aksak Maboul”, David Thomas, Daevid Allen, Lindsay Cooper and many others. What’s the story with the Gong and Aksak Maboul?

I started working with Gong whenever they were between drummers, or whenever Pierre Moerlin wandered off somewhere. That was back in the Henry Cow. There were a few tours over the years. Then Daevid asked me to come to Deja to work with him on a solo (non-Gong) album. That was shortly after Henry Cow broke up. Later, we headed out to Georgio Gomelsky’s Manifestival in New York (with a scary unscheduled stop in the Azores on the way) and then didn’t play together again for 21 years – until we went to Japan with Hugh Hopper as the second-generation Brainville. Aqsak was part of RIO and Marc Hollander had played in the touring version of Art Bears. He invited Fred and me to play on his second LP – also made with Etienne Conod at Sunrise. That was a great band of really exceptional musicians, meaty material and very productive. We also did a short tour with that line-up.

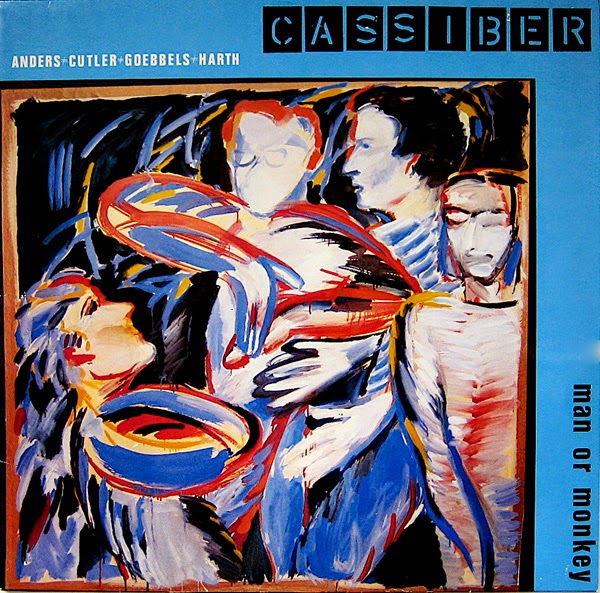

In the 1980s you formed “Cassiber” and later you played with so many artists that it’s almost impossible to talk about everyone, so I would be very glad if you could share a story about “Cassiber”.

Heiner contributed a piece to our Recommended Sampler in 1984. He used a drum machine. I said, do call me if you ever want some real drums. About a year later he did. We all met at Sunrise in Switzerland (where all the Art Bears LPs and Western Culture were made). It was just a recording experiment. The ideas was to improvise pieces that sounded as if they had been written and arranged (I wrote texts for Christoph to use if and when he felt like it). We were happy with the results, which turned out to be a double LP, and because of that we were invited to play at the old Opera House in Frankfurt.

The concert was televised, and because Cassiber was a pretty radical band for the time, and they were changing times, we attracted a lot of attention. More festival offers came in and Cassiber became a pillar of the German Neue Welle. After that we worked in bursts throughout the next 10 years, making another 4 albums, playing at just about every major European festival and going out to America, Japan and Brasil – constantly changing our ideas. The last LP was recorded in the academy of art in East Berlin. Which was unheard of then, for a Western band.

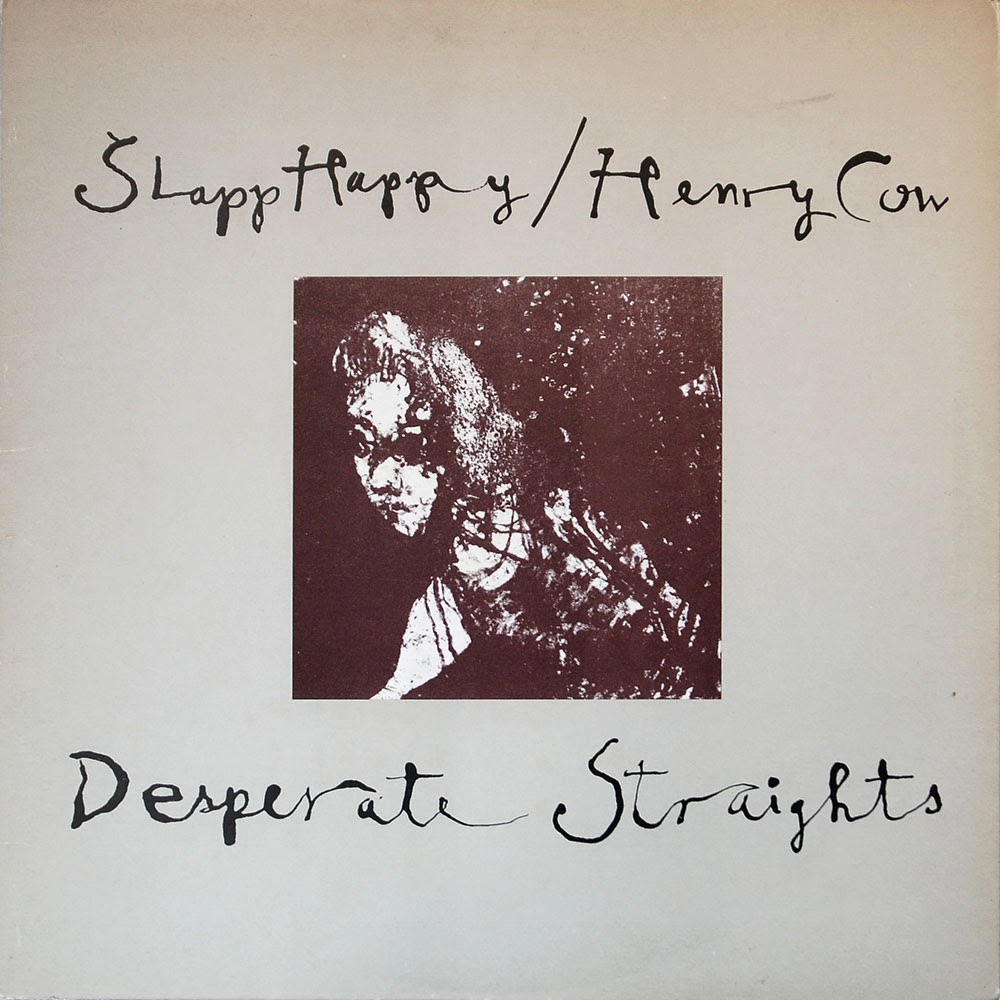

How about “Desperate Straights” album with Slapp Happy?

We discovered Slapp Happy by way of Faust. Sort Of (the first Slapp Happy LP) was made at their studio in Wumme, with Faust as the backing band. There was a second LP too, which was never released and Uwe Nettlebeck offered it to Virgin when Faust moved to Virgin. That’s when we met Slapp Happy. For some unfathomable reason Virgin decided to re-record the second LP with session musicians, even though the original, with Faust, sounded great. We all became friends. So when Virgin asked Slapp Happy for another record, Slapp Happy asked Henry Cow to be the band. After many Barcardis we decided to merge the two groups. Then we went to the manor and made Desperate Straights. That was fun: we worked on the songs while Simon Heyworth – another great engineer – manipulated the sound until we were all happy with it. Then we put it straight to tape. The title track was a single take of Anthony and I back in the studio early after dinner, playing a chord progression of Anthony’s – for no special reason – which Simon recorded without telling anyone. It stops when we stopped. And we never played it again.

You played several times in Ljubljana, Slovenia. My friend Aleks Lenard organized RIO festival and some other concerts…

Yes. We were several times in Ljubljana. We did a lot with ŠKUC. The first time was in the strawberry season and there was a tropical rainstorm. We ate a lot of beans and sheep cheese. Got paid in a bass-drum full of wine, met Laibach (very interesting people) and made a lot of friends.

Would you like to share anything else for It’s Psychedelic Baby Magazine?

Just to be fair to the many friends with whom I have worked with over the last 30 years, I should mention some of the other projects in my discography: News from Babel, Domestic Stories, p53, Pere Ubu, Hail, The Wooden Birds, Les Quatre Guitaristes de L’Apocalypso-bar, Music for Films, The Kalaharis Surfers, David Thomas and the Pedestrians, My long-standing duos with Fred Frith, Zeena Parkins and Thomas Dimuzio and The Peter Blegvad trio, not mention my Solo work with the electrified kit and my various Soundscape and Radio productions. Thanks to them all. My tip: always work with people more talented than you are.

– Klemen Breznikar

- Front.jpg)