Ron Geesin | Interview | “I’m still trying to find out who I became”

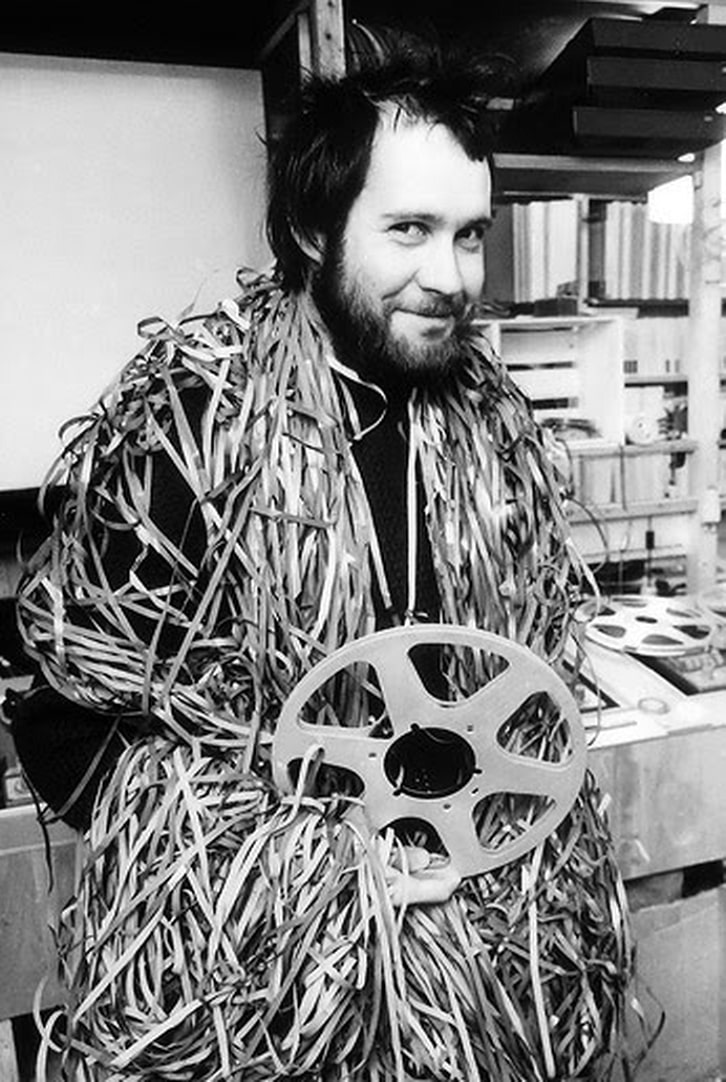

Ron Geesin is a composer, performer, sound architect, interactive designer, broadcaster, writer and lecturer.

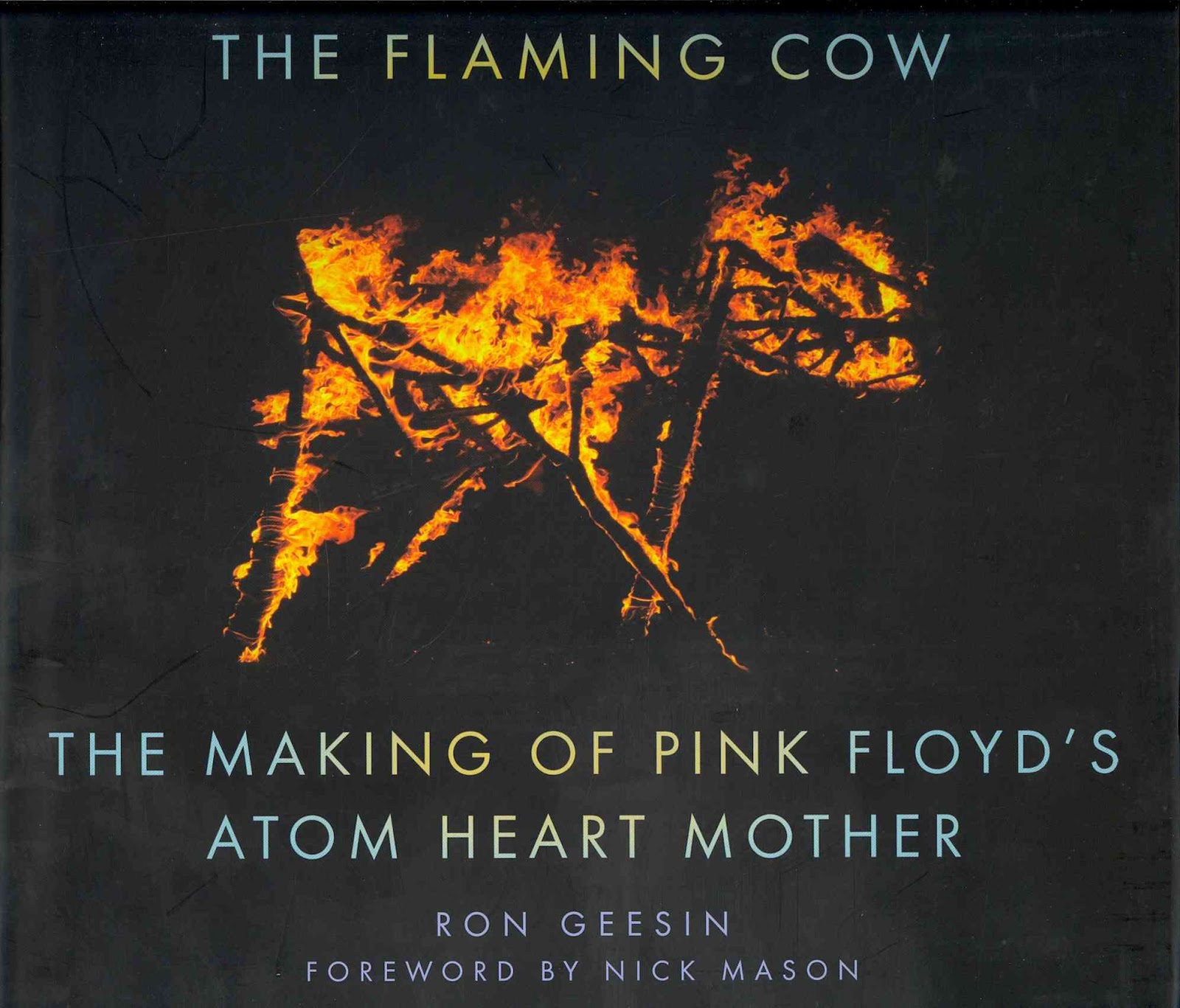

In the following interview we will discuss the making of Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother, his latest album RonCycle2, recently released book The Flaming Cow and new documentary.

“I’m still trying to find out who I became”

To begin with, when and where were you born and was music a big part of life in the Geesin household?

Ron Geesin: I was born on the 17th December 1943 at 6.10 am (Scottish birth certificates give the time). My Birth certificate says ‘Stevenston, Ayrshire’, but my mother always said that wasn’t quite correct: it was Kilwinning Maternity Hospital! Stevenston was where I was gestated. We moved to Bothwell, Lanarkshire when I was about 3: my father built a bungalow there. Music was not a big part of life: we did have an upright piano on which he stumbled through simplified bits of Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue and popular melodies from the 1930s and ’40s, “Red Sails In The Sunset” and “A Little Bit Independent” for instance, moving back to ragtime later.

At what age did you begin playing music and what were the first instruments that you played?

I got fairly fascinated by the ‘harmonica/mouth organ virtuoso’ Larry Adler, seeing him on the television, and was given a 12-hole chromatic harmonica, maybe when I became 11. I was soon playing bits of simplified Bach and the film theme from Genevieve. Then I got more interested in syncopated music in general: the ‘Trad’ (traditional jazz revival) era had started in the 1950s in Britain, so I got a long-neck ‘G’ banjo for my 15th birthday, took the short 5th string off and played it as a 4-string plectrum banjo.

You are a man of great talents. Composer, performer, sound architect, interactive designer, broadcaster, writer and also lecturer. What college did you attend? Would you say that it had any impact on who you became later on?

I’m still trying to find out who I became. I never attended a college. I was becoming extremely rebellious and unruly at Hamilton Academy (secondary school) and was asked to leave at around 17. “Take this boy away – we can do no more with him.” said the Headmaster to my father. This, supplemented by, “You’ll never be any good at anything!” by my father, caused me to get my head down, or up, and get on with real life – into that university – and out the other side.

You listed Victor Borge, The Goons, Chic Murray (Scottish comedian, deceased) as your main influences. You also mention Surrealism.

They were some of my main influences, but see below. Surrealism, in the visual medium, depicted the impossible, dream and subconscious images, often with humour. This connected well with the verbal equivalent ‘The Goon Show’ on radio. All this bundle of endeavour was my rocket fuel to get out of middle class materialistic Lanarkshire.

How about musical influences? How did you embrace Rock and roll?

My main musical influences were, and still are, classic Afro-American jazz from the 1920s and ’30s (actually musical surrealism), and most of the ‘classical’ composers’ works, except those of Britten, Shostakovich and Stravinsky. I never embraced any kind of ‘Rock’ – it came to me in the form of Pete Townshend, Peter Gabriel and Pink Floyd – I embraced these creators as individuals, but not their music.

“I could never copy anything anyway!”

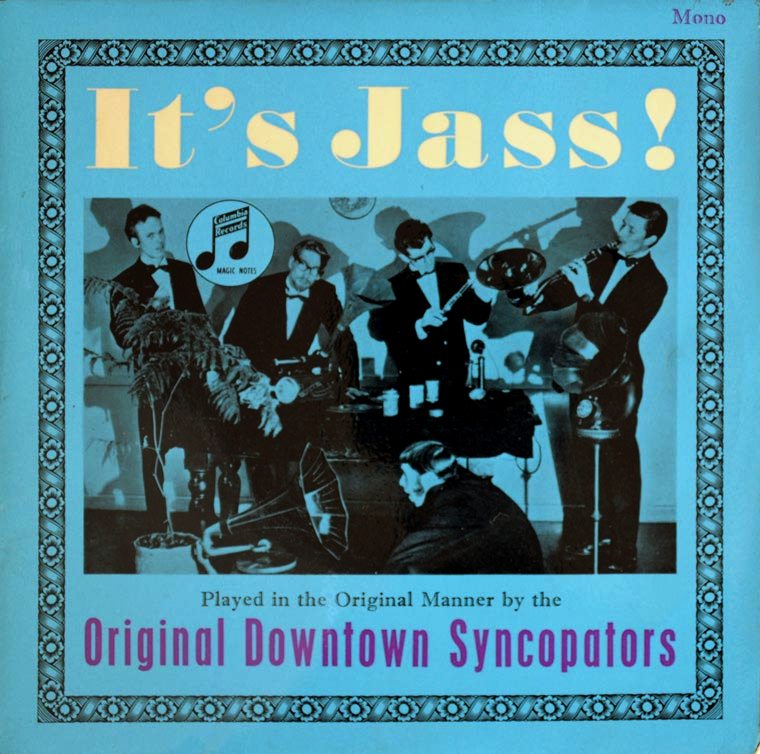

What were your first musical involvements? In the early ’60s you played piano on a few recordings, as the Original Downtown Syncopators. What can you say about this jazz combo? You released an EP on a major label in 1964.

I think you should prefix ‘musical involvements’ with ‘professional’. I joined the Original Downtown Syncopators in 1961 [see here and here]. As a passionate mid-adolescent, I always said they were a bunch of late adolescents having a fling before settling down. Their main aim was to copy the music of the very first jazz band to record ‘Jazz’, or ‘Jass’ as it was sometimes called in 1917, The Original Dixieland Jazz Band. Fortunately, the piano was fairly indistinct on those early acoustic recordings, so I just had to play within the general style – since I could never copy anything anyway!

“Composing, in music or ‘organised noise’, is about forming a structure: building modules by any means”

Improvisation is a big part of your life. What’s your view as a composer and performer on improvisational pieces?

Composing, in music or ‘organised noise’, is about forming a structure: building modules by any means. I have always enjoyed improvising as a way of allowing the subconscious to declare or reveal itself. If an improvisation is recorded, one can turn back on it, reflect and change if necessary. If not recorded, whoever hears it gets the picture – the executant might get some of it but is more free to move on. When composing in the more conventional way – writing onto manuscript paper – even when composing a solo melody, one might improvise a phrase many different ways, eventually settle and then write it down – draw the map.

What does it mean to you and to your perception to improvise?

Essential to the process of composing.

In 1965 you made an EP, which was recorded by Keith Knox in a club in NW London.

This consisted of four improvised piano solos – at a time when I had just moved from Crawley, Sussex, to London and left the Original Downtown Syncopators. Keith Knox was an amateur recording enthusiast from Crawley and we agreed to do some recording. It was only after I got the tape material that I thought to make an EP out of it. The recording was done one morning. A barman was clearing up glasses which can be heard clinking on one track: that’s why I called it “March Of The Wine Glasses”.

A Raise Of Eyebrows followed on Transatlantic Records.

One of my aphorisms is, “The easiest place to hide is in the Avant Garde.” If there ever was an ‘idea’, it was to make a collection of my contemporary capabilities, by whatever means. In fact, I went to Transatlantic (a rather grand front for a fellow called Nat Joseph) with some demo tracks and he said, “We’ll take a risk! Go and make some more stuff.” So, out came early prototypes of my types of utterance: surreal mini-dramas (eg. “A Raise Of Eyebrows”); spoken pieces (eg. “A Female”); improvisations (eg. “It’s All Very New, You Know”); written pieces (eg. “Two Fifteen String Guitars For Nice People”); tape manipulations (eg. “The Eye That Nearly Saw”) and; jazzy reflections (eg. “Ha! Ha!, But Reasonable”).

You contributed two atmospheric sections on Amory Kane’s album Just To Be There, John Peel Presents Top Gear, The Occasional Word by The Year Of The Great Leap Sideways and also on a record produced by The Who guitarist Pete Townshend (Happy Birthday). How did you get involved?

Survival! At that stage of one’s ‘careering’, one hears about things, one throws oneself on and off stages shouting, “Look at me! I can sing and dance, mister!”, and mostly one says, “I can do that!” and then works out a way to do it. And every thing done adds into one’s portfolio of life for others to experience and sometimes get attracted to.

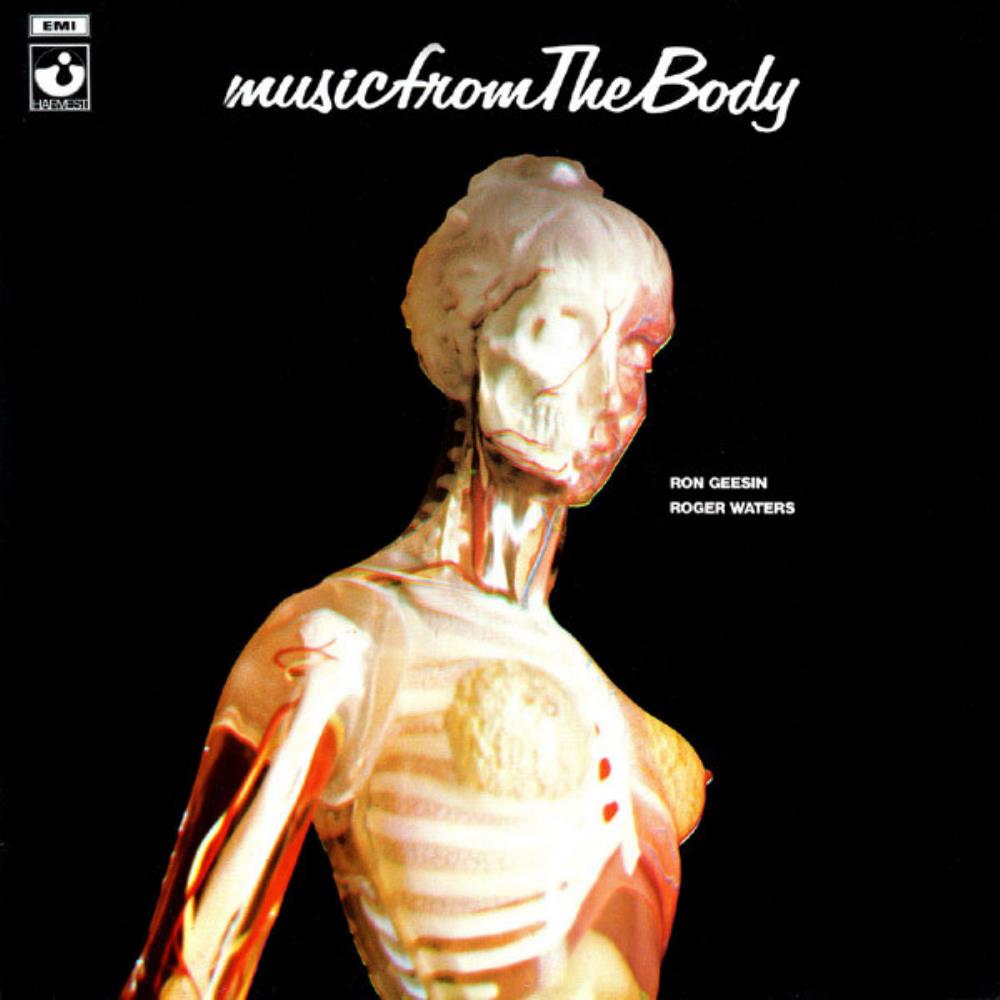

In 1970 English producer Tony Garnett decided to adapt Anthony Smith’s book ‘The Body’ to the screen. Interested in commissioning a soundtrack, Garnett asked BBC DJ John Peel for some recommendations. Peel promptly suggested avant-garde composer Ron Geesin. What’s the story behind getting to work on this project?

Well, you’ve just told it – the start anyway. Some more of it is in my book on the real story of the making of Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother, The Flaming Cow.

You knew Pink Floyd and decided to invite Roger Waters. Why him?

Because I had become particular friends with him, also enlarged on in the book, and he could do original songs, which was not my thing.

What’s the concept behind it? It’s supposed to be about the effect of music on the human body?

You’ve obviously not seen the film! It was an attempt by Garnett and director Roy Battersby to put a deeply socio-human documentary about the human body into cinemas, using some then-pioneering micro-camera work: coursing along the various tubes and all that. The soundtrack did what all film soundtracks are supposed to do: duet with the visual content, for, against, unison, comment. The subsequent album for EMI consisted of most of that soundtrack, in its many parts: mine as originally recorded, Roger’s re-recorded, supplemented by two original tracks, little to do with the film and all to do with Roger and me having fun, “Our Song” and “Body Transport”.

What was the process of getting ideas together with Roger Waters? It seems both of you had a very creative freedom to experiment on this one?

The process was not so much ‘together’ as, “Roger, you go and make the songs – here are the rough timings. I’ll go and make all the other sections, atmospheric and instrumental.”

Even Pink Floyd were involved with “Give Birth To a Smile”?

Yes, they happened to be around and still friends at that time! So they came in, solely for the EMI album, to supplement our endeavours.

What can you tell us about techniques you were using to make this album?

As a ‘one man operation’, I was fairly hooked at that time on a long delay tape system that played the magnetic tape across, or between, two machines so that everything that was picked up on the playback head of the second machine could be fed back through the mix onto the record head of the first machine. Then I wrote some pieces, such as for violin and cello: “Red Stuff Writhe” was originally for the Medical Titles of the film, but was dropped by Producer and Director, somewhat over-social reactionaries, because the classical-sounding violin and cello “glorified the medics”!! It was Roger’s idea to mix all the chosen sections for the EMI album out of one another to impart a feeling of journeying through the body.

How were you satisfied with the result?

Very!

Can you go more into details regarding your friendship with Roger?

Again, see The Flaming Cow.

What kind of music would you listen to when having a couple of beers together?

Very little of any kind. We were more interested in joking. I might have played him a few jazz 78s.

What about with other members of Pink Floyd?

I listened to fairly modern jazz with Rick Wright.

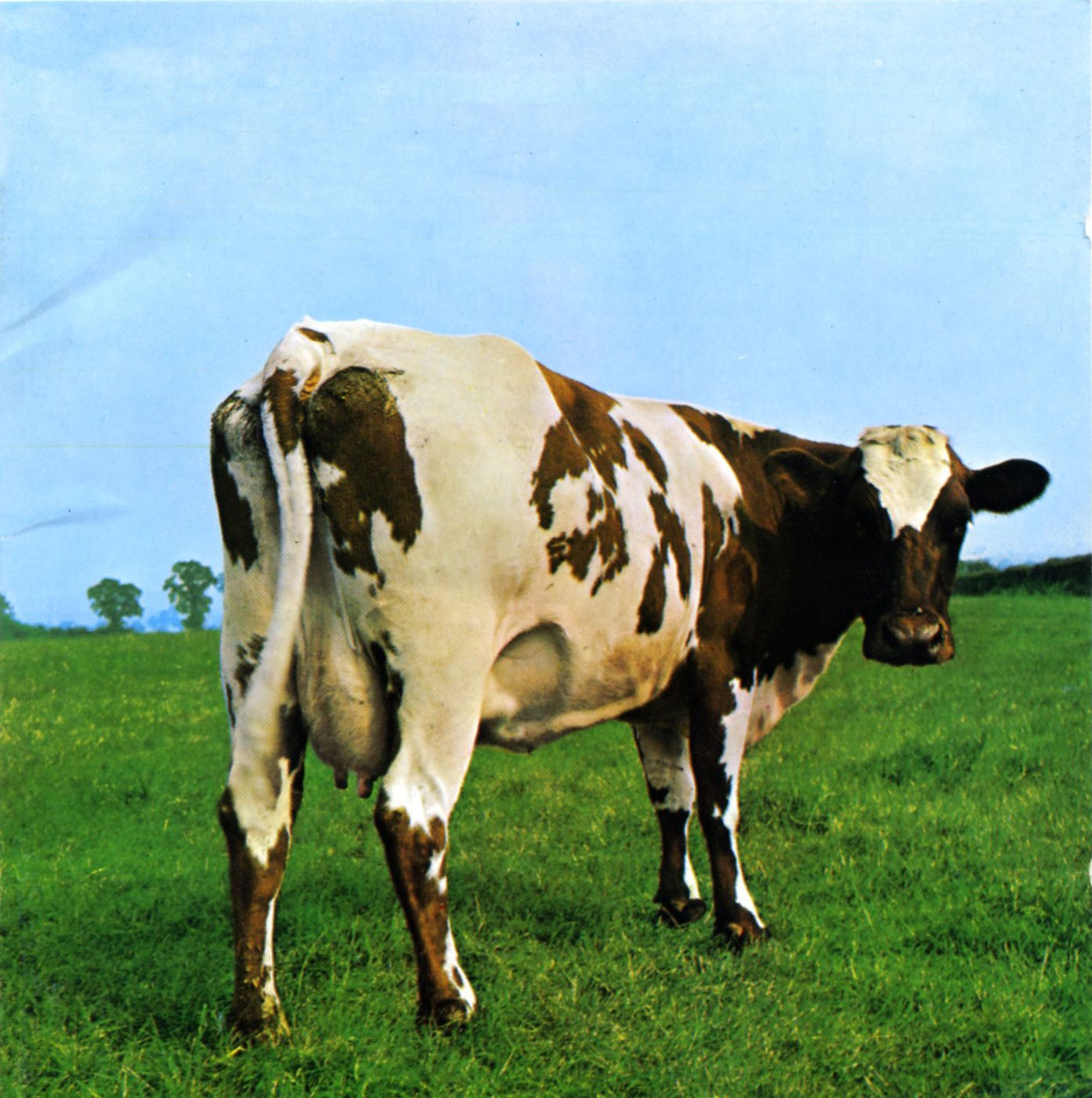

And now let’s move on to your involvement with Atom Heart Mother. Pink Floyd didn’t know what to do next and you were invited to be a big part of the band and their album. What’s the story behind it?

I’m not repeating what’s in The Flaming Cow.

How difficult was it to finalize Atom Heart Mother and would you say that you added your own concept to it?

I wrote all the brass, choir and cello on top of their backing track. Anyone who says anything else can see me in my study!

I read that it was pretty difficult to work with session musicians for the release? What was going on?

!@%@$£&()))(*!*+_+_(@^^%£&%^$ ! ! !

In 2008 you recreated Atom Heart Mother live on stage at the Cadogan Hall, Chelsea, London, featuring brass, choir, cello, and Italian Pink Floyd tribute band ‘Munn Floyd’. The work was presented alongside your solo performance; Atom Heart Mother itself was extended to 35 minutes, to take in a segment as written and again as recorded. The second night saw David Gilmour join you onstage for the performance. What memories do you have from this event?

Good to be back onstage. Good to have David’s exquisite lyricism flowing over. Bad to experience appalling management by the Royal College of Music, switching brass players through rehearsals and live, almost wrecking all the good work.

In 1972 you released a very interesting LP for KPM Records. Electrosound is an abstract electronic piece.

Someone at KPM Music Library (music for The Media: hire by the metre) enjoyed my work on ‘The Body’ film and asked me to make an LP’s worth of two minute electronic tracks that could be “used for The Media in general and had beginnings and ends, no fades”. So I went away and visualised patterns, not in any way about films, but mood and sound patterns. Having been properly amused in making them, I was subsequently more amused to find a pure piece of syncopation “Syncopot” used for a documentary that included beetles furiously scratching in desert sand. I became good friends with that director.

Electrosound (Volume 2) was released three years later, but in the meantime you managed to record As He Stands. Quite a different approach this time, wasn’t it?

This album was made up of a mixture of new compositions, prototypes of which appeared in A Raise Of Eyebrows, and remixes of more-commercial radio and film tracks.

Patruns, Atmospheres, Right Through and others followed.

Well, Atmospheres was actually the third KPM Music Library album. As a Jewish music agent once said, “Art for art’s sake. Money for Christ’s sake!”

Some of your latest releases are Biting The Hand and Roncycle1. Would you say that you’re using a different approach when it comes to composing?

Well, Biting The Hand is a collection of most, if not all, of my short pieces originally made for radio broadcasts, so they are what they are: different bits of my brain. RonCycle1: the journey of a melody is in the form of a complete journey.

It took more than 20 years to finish it…

From the notes:

This monster from the deep was started in 1986 as “Whatever You Fancy Next”, its closest ancestor being the 1976 album “Right Through”. As the idea took more shape, I changed the working title to the factual “Journey Of A Melody” in 1999. After the final mix in July 2010, I made a further list of 15 titles and then settled on a 16th, RonCycle1 – because there are enough meanings in the Oxford English Dictionary for the work to qualify as a cycle, and it is the first in an intended trilogy, the second being “Journey Of A Rhythm”. The reason that it has all taken so long is that, as it grew, it frightened me so much that I had to walk away for long periods. I am sure that it did not take up more than 3 years of solid working time.

Method

The overall plan, or sequence of events, was scribbled in words on a roll of paper, but not further than a few sections beyond the score. As this caught up, a bit more planning was done. I would also have Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Philosophy of Composition” in mind and sometimes work backwards from a landmark event. Working from the short score, I found or freshly constructed suitably toned and textured sounds as I went. Some parts were scored completely (eg. 5) while some others were written as top line and chords only (eg. 6), expanded into fast sequences direct in the computer, and others were built wholly in the computer (eg. 10).

So what’s the journey of a melody?

Again, from the notes:

Content – don’t read this if you want to make up your own story.

Here ‘Melody’ means ‘melodic line’, one of the two accepted, or universally identified, elements in music – the other is rhythm. Ideas or models for melodic lines can come from anywhere, from the tuning of a piano in this case. Extra notes are filled in to create a sequence, out from under which climbs a twisted monster melody whose notes are all derived from the sequence (1). Even at this gestatory stage there are interruptions. It settles down (2) and tries its legs along an open road but soon meets opposition in the form of an antagonistic voice (3). This might be asking, “Where are you going?” or “What are you doing to me?” Neither questions do much good in this abstract sound medium, so the frazzled melody breaks through some kind of partition, maybe of wire netting, and really settles into a glide out in the open with its feet just slightly off the ground (4a). Becoming rather precocious, it glides over a cliff (4b) and floats down into exotic undergrowth, through which it then moves with some difficulty (5), clawing its way through cobwebs and creepers, into and out of sunlit areas, up to some kind of huge building or cave housing very unfamiliar and misshapen creatures, some of whom may be mining or trying to escape (6). The melody has got fairly fluent and mature by this time. It climbs or slides up a slope into a hall of weathercasters, all pronouncing solemn judgements and predictions about that Great British transfixation (7). The melody is induced into an even more solemn state and circles the commentators. Underground becomes overground as we hover in a disorienting wispy mist (8). Suddenly, we encounter an enormous blackbird that has been practising the melody and are so distracted that we fall into a cellar where a jazz combo is being led by a talking saxophone (9). This cellar is in fact the foyer of the BBC’s Broadcasting House in the form of a very dusty valve radio (10). Presenters emerge from the valves to comment on the composition that has dared to invade their hallowed space. The melody turns upon them and encourages them to sing along (11). This new ensemble is temporarily moved to form a new group, but arguments between it and the melody soon grow (12). Exhausted by this activity, they all sit down, or fall over, and an Eastern European ethnic musician seizes the opportunity to entertain (13). Having rested and gathered new energy, the melody joins in, gathering up elements from its colourful journey (14). The flame is lit, and situations and characters from the journey turn up, join up and romp forward, or back, to home (15). That place is reached, but I have not closed the toilet door and am discovered still practising how to start! (16)

There was also a book published by The History Press about your collaboration with Pink Floyd.

Yes, The Flaming Cow!

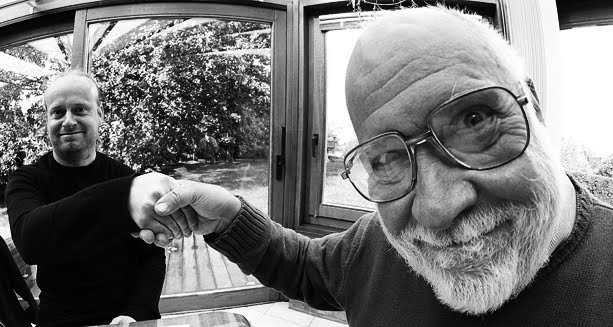

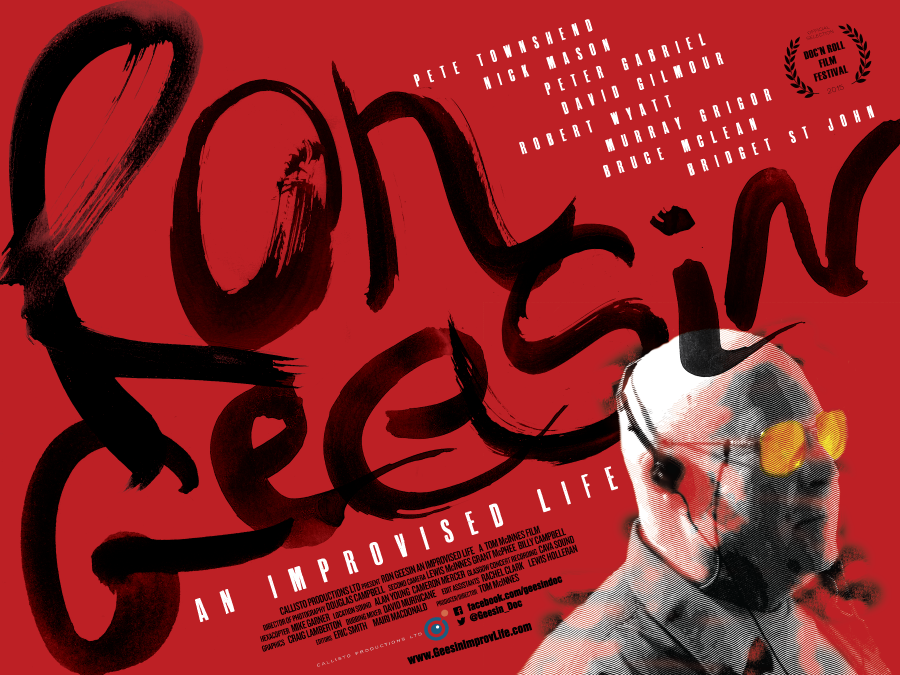

Ron Geesin: An Improvised Life is a new documentary about your life.

This was started when director Tom McInnes of Callisto Productions shot my last full live performance – in Glasgow, 2013 – then decided to make a full documentary around it. Well, it could never be ‘full’, but it’s selectively comprehensive.

What currently occupies your life? Any future projects we should expect?

The most gripping tale The Adjustable Spanner – History, Origins and Development (in the UK) was published in March 2016 by The Crowood Press. Nothing to do with organised noise or performance, except perhaps through the tenuous link of structure and form. This has taken me 25 years to research and write and will further confuse anyone who tries to pin down what I’m about. See the tour here.

Now I’m getting back in the studio to pursue RonCycle2 – the journey of a rhythm.

Would you like to send a message to It’s Psychedelic Baby readers?

When in doubt, spin about.

When behind, feign being blind.

When ahead, go to bed.

When in sky, flap and fly.

When you’re dead you’ve got there.

Klemen Breznikar

Ron Geesin Official Website

Fascinating interview Klemen – you dig deep!! Keep up the good work!!