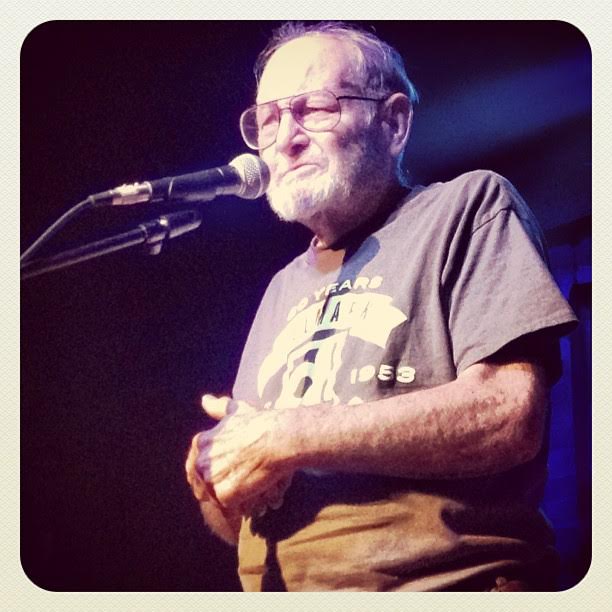

Interview with Delmark Records Founder Robert G. Koester

Robert G. Koester’s visionary passion birthed Delmark Records, a seminal label that has come to define the spirit of Chicago’s jazz and blues scene.

His unwavering commitment to authenticity cultivated a catalog brimming with groundbreaking artists, with each recording capturing the unvarnished soul of American music. In our intimate conversation, Mr. Koester recounted tales of serendipity, struggle, and triumph that have shaped the label’s storied legacy.

Founded in 1953 in Chicago, Delmark Records emerged as a pioneering force, immortalizing the essence of urban blues and the innovative pulse of jazz. Its early recordings laid the foundation for a musical revolution, intertwining the visceral energy of live performance with the permanence of recorded history. Today, the label continues to inspire both seasoned aficionados and emerging talents, standing as a living tribute to Koester’s enduring vision. As a music journalist, I find that his narrative encapsulates the true spirit of jazz: improvisational, fearless, and eternally resonant.

“I am usually behind the music—it took Joe Segal some more time to get my head into bop.”

Where does your love for jazz originate? Which musicians first captured your interest and stood out as unique?

Robert G. Koester: There wasn’t much jazz where I was born in Wichita, Kansas, but I managed to hear an Eddie Condon show on a network not carried in Wichita from a station in Oklahoma. I may have first gotten interested in jazz when my folks moved into my grandfather’s house, where there was a large 78 collection consisting mostly of classical music. One of the DJs on local KAKE played some jazz—’No Name Jive’ by Glen Gray’s band. Bear in mind that big band swing was the pop music of my teen years.

The first live jazz I heard was a local band, but I think I managed to hear Kansas City tenor man Tommy Douglas once or twice. Julia Lee was one of my favorites, she got me into blues, but my parents wouldn’t let me go see her or Jay McShann when they came to town. I didn’t know about the Monday night Black bands at the Blue Moon, or I might have made it there.

You’ve experienced so many different eras of jazz. Which period do you think was the most exciting for the music?

Well, I always preferred traditional jazz (and I hate the word “Dixieland”), but thanks to Don Hoffman in Wichita and Joe Segal in Chicago, I developed an appreciation for modern jazz. In Wichita, I picked up whatever I could find at the Salvation Army, secondhand stores, or from jukebox operators. The guy who ran the Record Shop had bought a lot of old 78s, including pre-war records from Chicago, so he had stuff that had probably never even been sold in Wichita.

I was able to buy records from two Black jukebox operators, including some Robert Johnson. Now that I know blues is at the heart of all jazz, I wonder why so many white listeners looked down on blues in those days. But that just meant they left a lot of great records behind at the salvage stores. I was mostly interested in Black bands and combos, including Lucky Millinder and Jimmie Lunceford.

Delmark Records originated in St. Louis, Missouri, in 1953, during the rise of the bebop movement. That must have been an exciting time and place to launch a label dedicated to jazz and blues. What was that experience like?

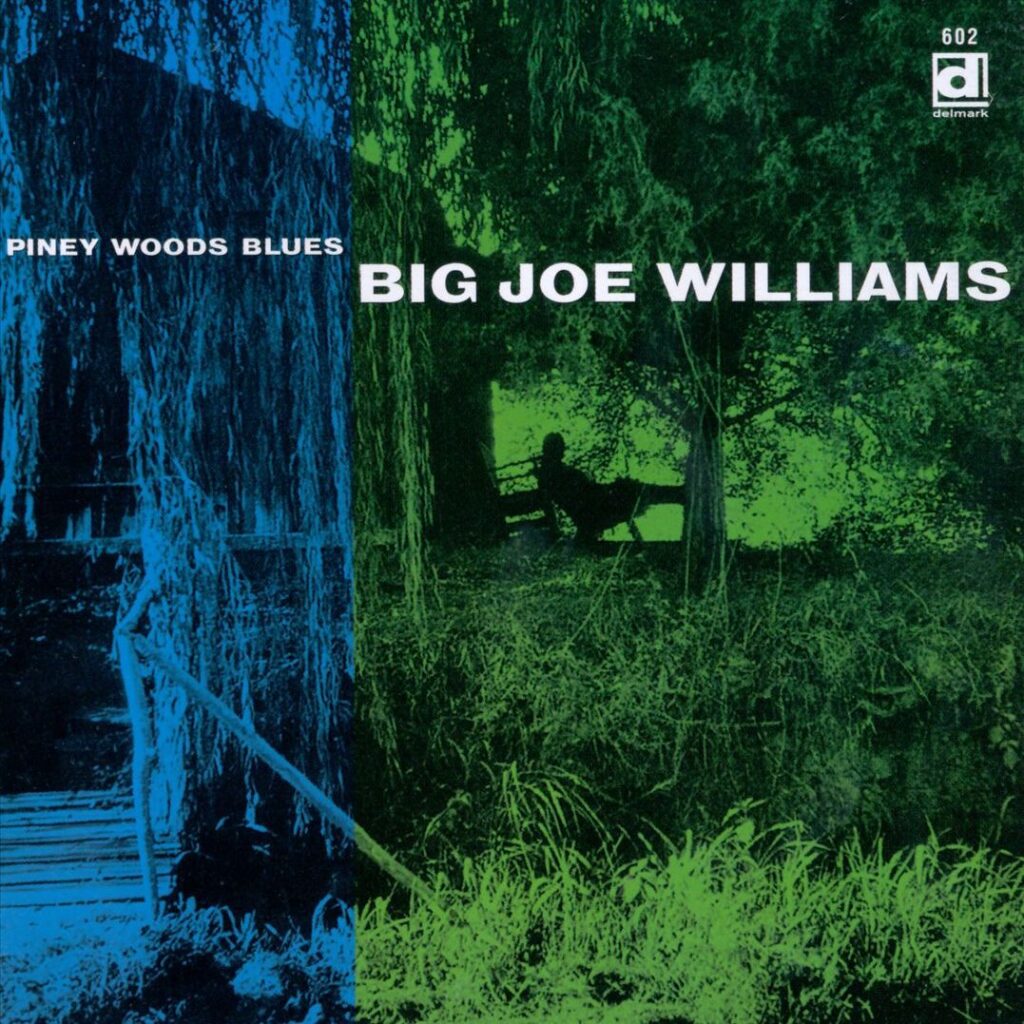

I’m truly sorry I wasn’t into bop enough at the time to record Jimmy Forrest or Oliver Nelson. When I was in St. Louis, it took me a while to even appreciate Bob Graf. I recorded Speckled Red because I liked boogie-woogie (more than blues at the time), but Big Joe Williams turned me onto country blues as a living, breathing music.

St. Louis had more music than I could keep up with. I met Walter Davis, Edith Johnson, Henry Brown, Stump Johnson, and others, but I didn’t have the money to record them. I should also mention that I wasn’t allowed to enter the Black club where Lonnie Johnson was performing in Wichita… the sheriff wouldn’t allow mixed crowds. I suppose that also kept me from hearing the mainstream and pop musicians who played in Black clubs in St. Louis.

Before starting your label, you were an avid record collector and trader, building your business around records. How did that passion develop?

Glenn Miller’s contract with RCA was apparently too steep for them to keep much of his catalog in print, so there was a strong demand for his records. They weren’t too hard to find, but they were highly sought after, so I always had spare copies to trade or sell. There was one collector in Wichita who specialized in Miller, which was great because he spent a lot of time at secondhand stores, the Salvation Army, and similar places.

The first ad I placed was in Mimeo, a Canadian magazine, where I sold all the Glenn Miller records I advertised, but that was the end of my merchandising until I moved to St. Louis. When I went to college, it had to be a Catholic one, so I chose St. Louis University. A traditional jazz club was just a block from campus, and two Black dorms were across the street from the western edge of the Black neighborhood. I was also about four blocks from the leading modern jazz club, which allowed white patrons, and near the bar owned by Charlie Thompson, who had won the last ragtime contest in 1916 and recorded for Bill Russell’s American Music label.

How did your record store evolve into a record label?

I met Ron Fister, who mostly collected sweet big bands and Billie Holiday, and we opened the Blue Note Record Shop. The first jazz band at the first club we worked with was The Windy City Six (later The Mound City Six), and they became Delmark’s first studio project.

Before starting the label, I spent a lot of time at the Barrel, a club on Delmar, where I heard a band featuring Dewey Jackson (trumpet), Frank Chace (clarinet), Don Ewell (piano), Booker T. Washington (drums), and former St. Louisian Sid Dawson (trombone). I had a radio show on the student station, though I was too introverted to do the announcing, where I played jazz records for a small audience. The announcer for the show was able to borrow a professional tape machine, and we recorded Dewey and the others.

Years later, when I considered releasing the tape, it was in bad shape. But when digital technology came in, we were finally able to issue it not long ago, in fact. Unfortunately, it had very disappointing sales. For reasons I still don’t understand, jazz magazines largely ignored it. And, of course, there’s little to no traditional jazz being played by jazz DJs these days.

You began searching for local talent and discovered many incredible artists, including Big Joe Williams, Speckled Red, James Crutchfield, J.D. Short, and others. What was that search like back then, and how did you first encounter the legendary Big Joe Williams?

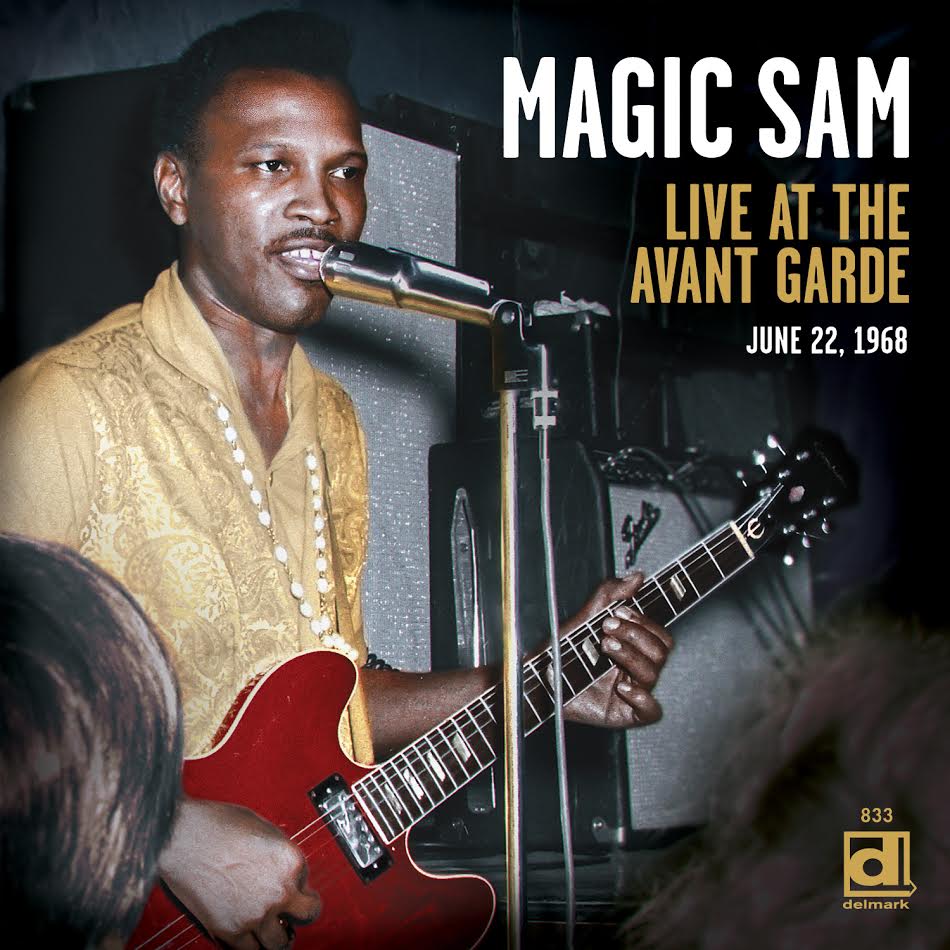

The blues bands I heard in St. Louis seemed so derivative and disorganized that they didn’t interest me, though I had a lot of Junior Wells, Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, Magic Sam, etc., in my collection.

A police lieutenant named Charlie O’Brien, a fellow member of the St. Louis Jazz Club, wanted to test his skills by tracking down some of the old musicians. The club had already found the old traditional jazz guys, but since they had sadly decided to limit performances to trad jazz (though they did make exceptions for Big Joe Williams and Speckled Red), I gave Charlie a list of St. Louis bluesmen who had recorded over the years. He found them all or learned of their passing. Charlie deserves the few tunes dedicated to him by various artists.

None of us actually sought out Big Joe Williams… he somehow heard of my interest in blues and just showed up at the Blue Note Record Shop one day. He wanted us to hear him and his cousin, J.D. Short, at a home in the ghetto. I already had most of Joe’s 78s on Bluebird, Trumpet, etc. (as well as his great Columbia records), so I knew of his immense talent. He agreed to record a massive amount of material, even beyond what he was being paid for at the time.

J.D., however, had to be paid immediately, so we never finished his project. Joe also told me he knew a lot of other artists from his travels—Sleepy John Estes, Kokomo Arnold, and more.

In 1958, you moved to Chicago. What led to that decision?

I moved to Chicago because John Steiner urged me to do so in order to buy his Paramount holdings. During my years in St. Louis, I used to visit his place on Ashland (which he shared with Bill Russell of AM Records). In his final letter to me, which I still have and want to frame, he wrote, “Get going, young fellow.” So I did.

Later, he loaned me the money to buy Seymour’s Record Mart, the Chicago jazz shop at 439 S. Wabash. But I became interested in recording Chicago blues and jazz. Besides, Riverside had a no-end-term lease and had already issued all the great jazz records, plus Ma Rainey, so I decided to focus on Chicago blues and jazz artists. Joe Segal handled the bop scene, and the artists themselves explored avant-garde jazz. I wasn’t particularly into the avant-garde, but I trusted Don DeMichael, Pete Welding, and others who encouraged me to pursue it.

St. Louis had some avant-garde artists, but I wasn’t aware of them at the time, and perhaps no one would have wanted me to record them.

So in the end, the AACM and the blues took precedence over Paramount for Delmark. I don’t mind.

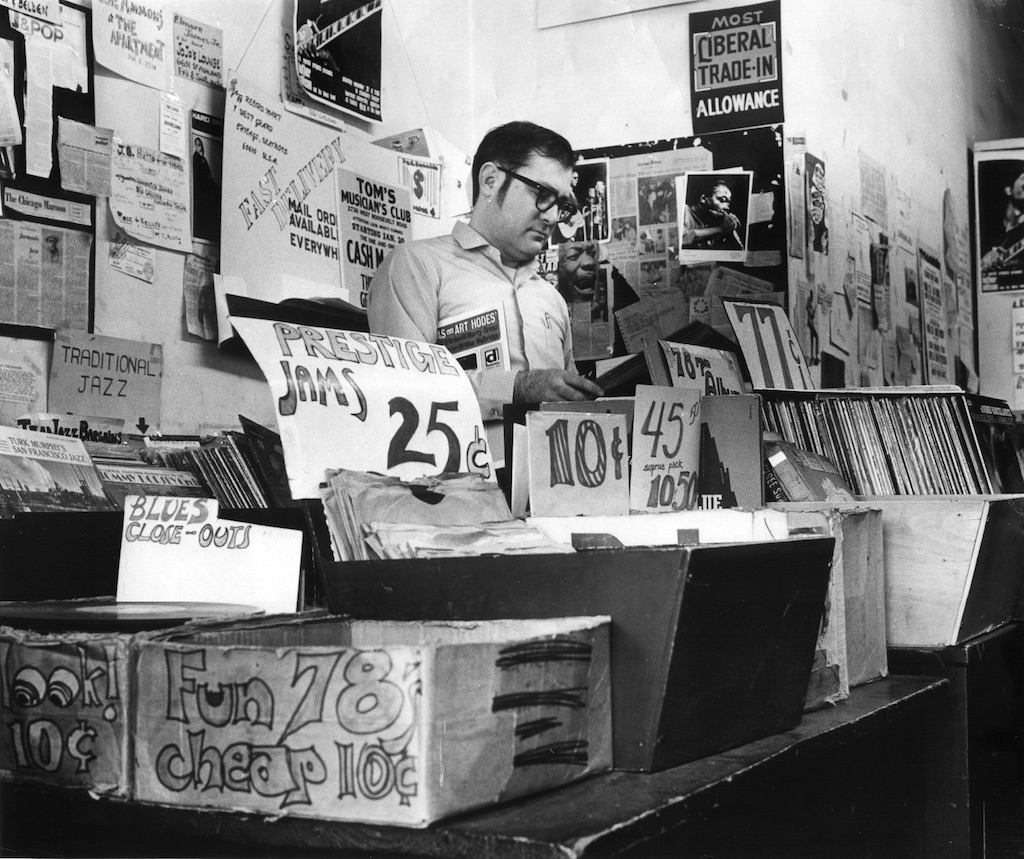

You bought Seymour’s Record Mart and later renamed it Jazz Record Mart, which became part of Delmark Records. As the Delmark catalog grew, you released albums by artists like George Lewis, Barney Bigard, Jimmy Forrest, Bud Powell, Donald Byrd, Ira Sullivan, and blues legend Sleepy John Estes. What was the process of finding and signing artists like?

I didn’t rename Seymour’s until I had to move the shop because the Roosevelt University Building was expanding into our space. The original name was Seymour’s Loop Jazz Record Mart, but since we were no longer in the Loop and Seymour was gone, I removed those two words.

When I acquired the shop, I thought it was virtually out of business. But thanks to Joe Segal, who had previously worked for Seymour and later returned to work at 439 S. Wabash—we built up a strong modern jazz stock and following. Joe eventually started producing our modern jazz albums, including recordings by Ira Sullivan, Jimmy Forrest, and John Young.

When Harry “Sweets” Edison came to town, we recorded his sidemen, including Jimmy Forrest. We also brought Grant Green up from St. Louis—I had wanted to record him before I left for Chicago.

Many of our releases, including albums by Donald Byrd, Sun Ra, and George Lewis, were acquired from defunct labels like Transition and Antone. We got Bud Powell and Archie Shepp from Storyville in exchange for European rights to one of our albums.

Sleepy John Estes’ first album was originally recorded by E.D. Nunn for Audiophile Records. After moving to Chicago, I usually recorded at Hall Studios. However, when engineer Stu Black moved to Chess, we ended up doing a lot of sessions there.

When I bought our building at 4121, cornetist Paul Serrano dropped by and suggested we buy out his studio equipment (which we had been using after Stu left for Chess). We did—and we’ve been there ever since.

Where did Delmark artists record? Did you have your own studio, or did you collaborate with local Chicago studios?

The early 10” LPs were recorded in a private studio in the home of Robert Oswald. His wife was a major supporter of the St. Louis Jazz Club, which unfortunately later decided to focus only on traditional jazz, even though Clark Terry attended their first meeting. We recorded The Windy City Six, Sid Dawson, and the first Dixie Stompers album there.

The second Dixie Stompers album was recorded on a riverboat bar. I can’t remember what equipment I used.

Speckled Red was recorded at the home of John Phillips, another St. Louis Jazz Club member with a great record collection, including a lot of blues.

I recorded Big Joe Williams at my Blue Note Record Shop.

Through the 1960s, jazz and blues evolved, and so did the music industry. You managed to release albums by artists like Sun Ra, Junior Wells, and Luther Allison—some of the greatest names in jazz and blues. What was that era like for Delmark?

The Sun Ra and Donald Byrd masters were purchased from the defunct Transition label (which sold its other recordings to Blue Note). At the time, Sun Ra was still a “local” artist, and his manager ran their own label, Saturn. I was surprised by how well the Sun Ra records sold, but his reputation had already grown beyond just local recognition.

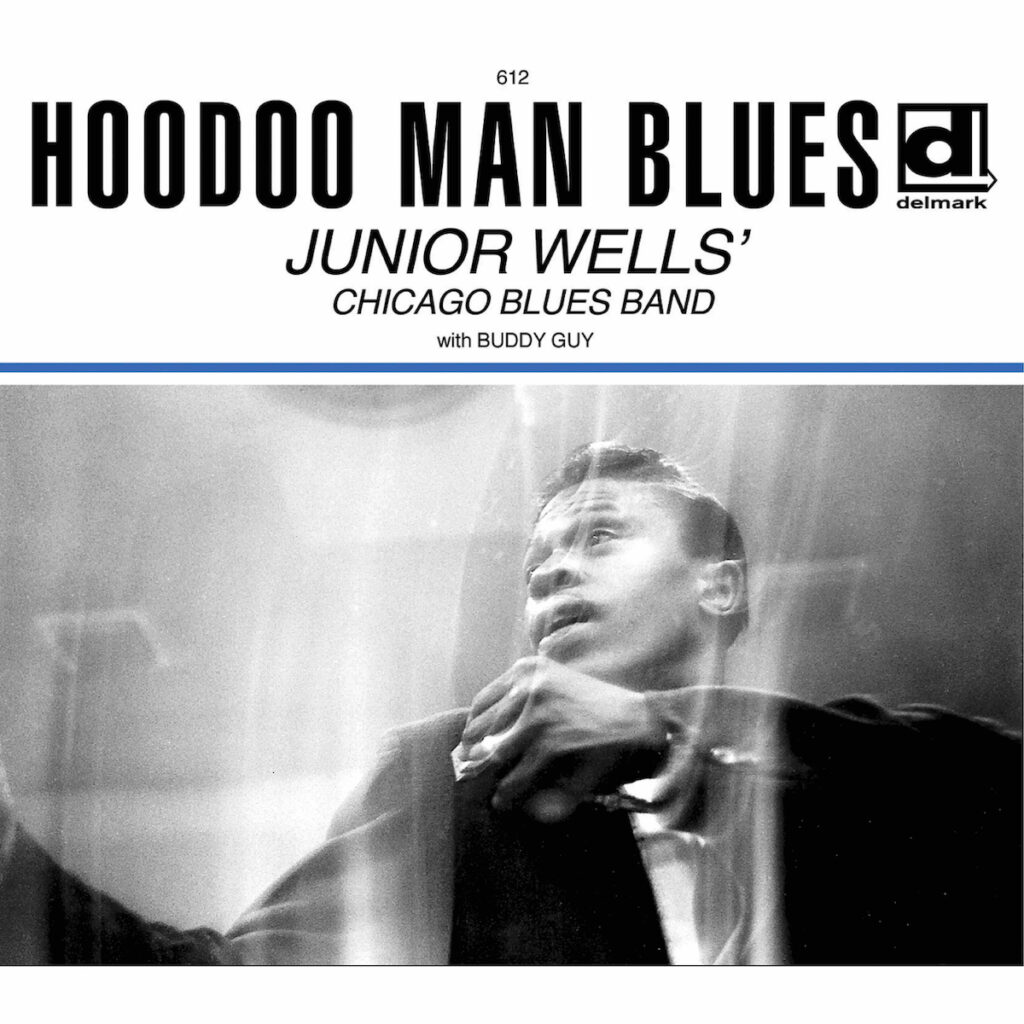

I initially worried that the white blues audience wouldn’t like Hoodoo Man Blues by Junior Wells’ Chicago Blues Band, but I was completely wrong. Many of them had been into country blues, but through Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, they had transitioned to Chicago blues bands.

A guy named Bill Lindeman introduced me to Luther Allison. Bill had recorded two tracks with Luther in a partnership with harmonica player Shakey Jake.

Junior Wells signed with Vanguard after the success of Hoodoo Man Blues. Once that contract expired, we recorded Southside Blues Jam. Later, when his contract with Atlantic ended, we released On Tap. Then we acquired the United label masters and reissued Junior’s earliest recordings with Muddy Waters and Elmore James, who he had been playing with at the time.

Unfortunately, Luther Allison later signed with a manager who made demands for further recordings that were beyond what we could accommodate. That was a real loss for us, as he was a brilliant and unique artist who didn’t record as much as he should have before he passed away.

The Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians helped you release many interesting acts, giving them an opportunity to be heard. How did your involvement with AACM come about?

I must admit I was not at all hip to avant-garde jazz. But when Pete Welding, Don DeMichael, and others urged me to record Roscoe Mitchell and others, I did so. As with all our recordings, I don’t “produce” them—I document them. If the artist can’t produce their own music, I can’t.

Were all the avant-garde artists you worked with part of AACM?

Not all avant-garde guys were in the AACM. I don’t know exactly who was and who wasn’t.

You also worked with Kahil El’Zabar. How did his music fit into your catalog?

Kahil El’Zabar may have been in the AACM, but I found his music less “out” (perhaps I was getting more hip to it). I am usually behind the music—it took Joe Segal even more time to get my head into bop.

Delmark Records is still going strong. What are some of the latest releases you’d like to highlight?

Please see our catalog: the 5000 series of jazz and, later, the 800 series of blues.

You come from a generation that has witnessed significant changes—not just in the music business, but also in format. These days, streaming dominates, but there’s also renewed interest in vinyl. What are your thoughts on the vinyl revival, digital streaming, and the current music business model?

I’m glad vinyl is making a comeback. We kept a lot of items in print on vinyl, but I had the pressing plants scrap most of our LP jacket inventory. I have a photo of myself beside a dumpster filled with LP jackets that I wish we still had so we could press them again.

LPs cost about $3.60 for pressing, printing of jackets (and manufacturing), and shrink-wrap. That’s after several hundred dollars for the master lacquer and metal parts. CDs cost less than a dollar for pressing, printing, and shrink-wrap. That’s why LPs cost $20, while CDs are $15.99. And that’s why a lot of releases won’t appear on LP.

Downloading is a dirty word in the record business today—it’s killing us. Sales can drop as low as half of one percent in the second year after releasing a new album.

If you had to pick a few records from the Delmark discography that you consider the best, most influential, or the ones you’re most proud of, which would they be?

The ones that the public and critics liked the most, plus the ones that got ignored and sold terribly few copies:

209 – Albert Nicholas With Art Hodes – ‘Albert Nicholas With Art Hodes’ All-Star Stompers’ (The only recordings of a fine New Orleans clarinetist)

219 – Paul Lingle – ‘Live’

233 – Percy Humphrey – ‘Climax Rag’

246 – Dewey Jackson – ‘Live at the Barrel 1952’ (A great St. Louis trumpeter, an idol of Miles Davis)

250 – Garvin Bushell & Friends – ‘One Steady Roll’

416 – Leon Sash – ‘I Remember Newport’ (A unique and great jazz accordionist)

424 – George Freeman – ‘Birth Sign’ (A fine guitarist, brother of Von Freeman)

454 – Jodie Christian, Larry Gray, Vincent Davis – ‘Experience’

488 – Eric Alexander & Lin Halliday – ‘Stablemates’

491 – Carl Leukaufe – ‘Warrior’

509 – Cecil Payne – ‘Payne’s Window’

512 – Francine Griffin – ‘The Song Bird’ (The only jazz vocalist I ever wanted to record—and could)

515 – Eddie Johnson – ‘Love You Madly’

520 – Harold Ousley – ‘Grit-Grittin’ Feelin’’

579 – Sabertooth – ‘Dr. Midnight: Live at the Green Mill’

605 – Curtis Jones – ‘Lonesome Bedroom Blues’

637 – Edith Wilson With Little Brother Montgomery & The State Street Ramblers – ‘He May Be Your Man (But He Comes to See Me Sometimes)’ (The first Black blues lady!)

“And if you’re only into blues, check out jazz—it’s totally based on the blues.”

What are Delmark Records’ future plans?

To keep going, but only recording artists who sell their music at concerts, because the market drops to 0.5%, not 5%, after the first year.

My son also works here, though he has a license to be a lawyer and will inherit Delmark after Susan and I are gone. (Susan is a full-time employee as well.) Steve Wagner has become very important here, he handles most of the production and is our chief engineer in the studio, which occasionally brings in extra money from rentals.

I’m 83, but I’m very stubborn and in good health (though I sometimes have memory issues from a stroke 15 years ago). I swim on weekdays. My doctor says I’m in surprisingly good condition.

Thank you for your time. Would you like to share a message with our readers and music fans in general?

Please don’t steal music. It cheats the authors, writers, performers, as well as the labels and record shops.

And if you’re only into blues, check out jazz—it’s totally based on the blues.

Klemen Breznikar

Delmark Records Official Website / Facebook / Instagram / X / YouTube / Bandcamp