Benjamin Delaney Lion

In the galaxy of UK private press LPs there are still some obscurities that are yet to get their time in the light. One such release is the excruciatingly rare album from Benjamin Delaney Lion, a folk duo who recorded a sole LP in July 1969.

Pressing up less than a hundred copies with a poetry book included, their work has remained largely unheard until one track ‘Samantha Carol Fragments’ appeared on the Dust on the Nettles compilation released on David Wells’ Grapefruit label in 2015.

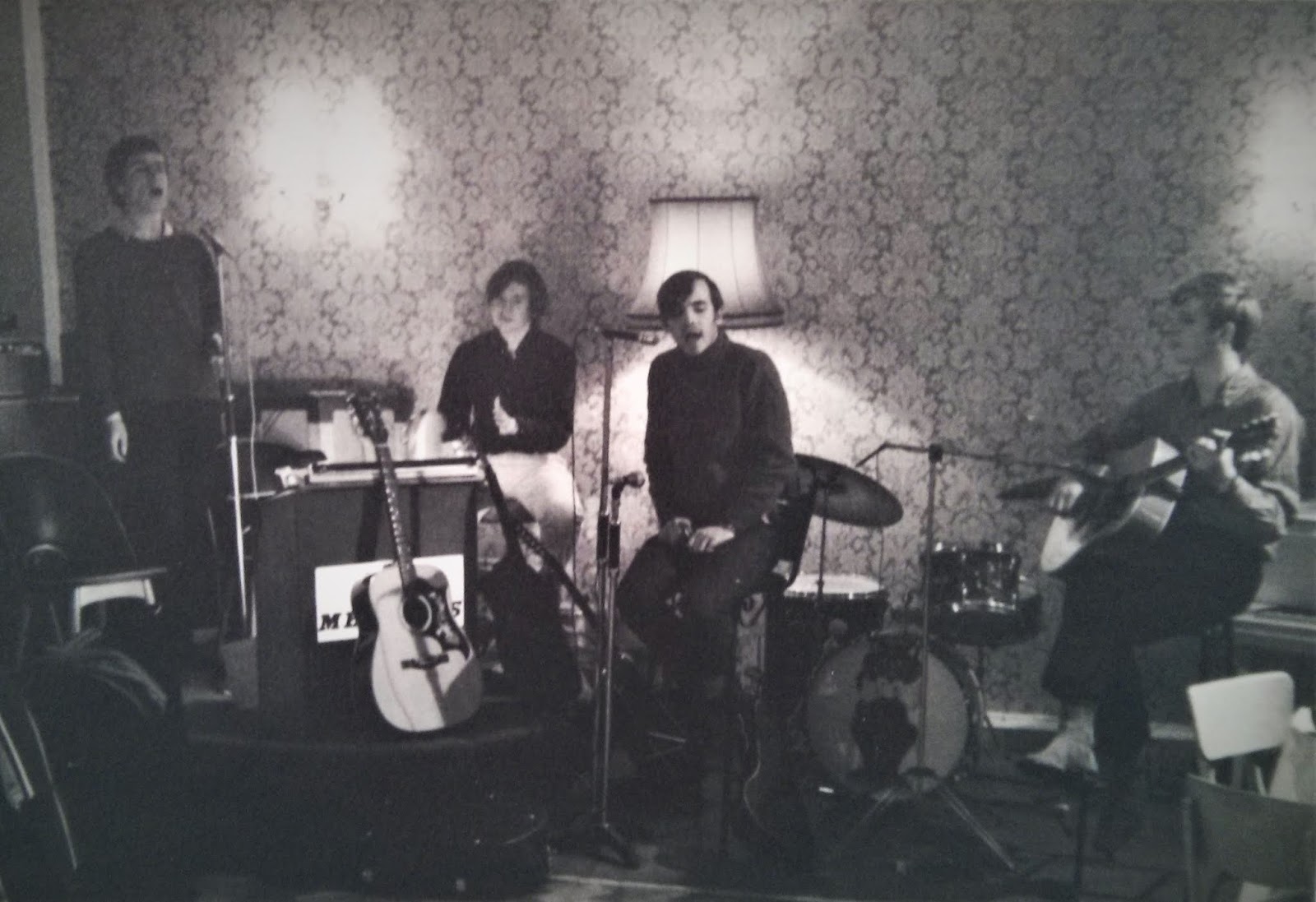

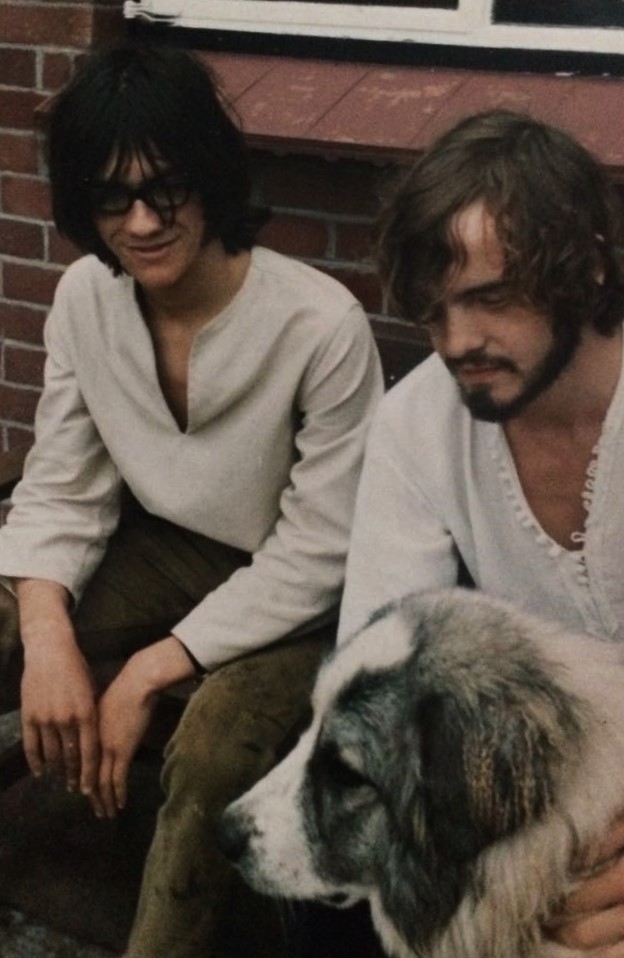

The band was comprised of teenagers Adrian Lewis and Roger Latham who met at Wrekin College in Shropshire at the tail end of the ‘60s. Their gentle hippie-folk songs owe a substantial debt to the Incredible String Band, whose songs they cover four of. The main draw of the album, however, is the six originals they play, which are all strong efforts with mystical lyrics and delicate arrangements, and are certainly not out of place with their more famous neighbours. All copies came with a 48-page booklet of poetry and illustrations from the band and other contributors. Adrian Lewis shares their full history here:

Where were you born and brought up?

Adrian Lewis: I was born in Swansea (September 1952) then went to boarding school in Shrewsbury from 9 – 13, then on to Wrekin College. Roger was born in Liverpool (April 1951) and moved to Burton on the Wirral at age of 2. He went to Chester Cathedral Choir School from 11 – 13, then to Wrekin.

How did you originally get into music?

Adrian: I got my first guitar when I was 9 but it was unplayable, and I quickly got fed up with trying to learn f with bleeding fingers. Finally I got a playable guitar in the shape of an Eko 12-string for Christmas when I was 11. Folk music was all that seemed possible as an aspiring solo singer/guitarist, until I discovered Donovan in 1965, then ISB and Tyrannosaurus Rex, then Davey Graham. I had already got heavily into poetry as an introverted boarding school inmate, and once I could play a bit, songwriting seemed the next logical step. Roger had piano lessons from an early age, then choir, choral society etc before picking up guitar.

How did you and Roger meet and come to play together?

Adrian: We were both active members of the Wrekin Arts Society, and I seem to remember asking Roger if he fancied doing a couple of Simon & Garfunkel covers together for one of the Arts Society “productions”, which were always (mostly) self-written and produced, and it must have started there.

How did you choose the name of the band?

Adrian: I was on a bus trip with my old school-friend Chris Mears; I have no idea where we were going. We had been discussing the band name for the album (I had set one of Chris’s poems to music for the album and several of his poems are included in the booklet) when we passed a building site with a hoarding advertising the “Benjamin Delaney Alliance”. Chris said to me “that would be a good name for a band” while repeating it, but I misheard it. And so Benjamin Delaney Lion was born.

Were you playing in folk clubs together? What was your method for writing songs?

Adrian: No. I started playing in folk clubs (specifically the Ballads & Blues Club at the Adelphi pub in Wind Street, Swansea, run by the late Dave Yoxall), straight after I left school, probably in Jan/Feb 1970. Roger informs me that we did a gig together in Wellington (Telford) while we were at school, in some hall or other which was arranged by someone at Wrekin, although I have no memory of it! I believe we may have played together at the Traverse Theatre in Edinburgh when we were up at the Edinburgh festival in 1969 and we definitely did a New Year’s Eve gig at a club on the Wirral on 31/12/1969. The first song we played after midnight was the ISB’s “Back in the 1960s”, which we were quite amused by at the time!

What made you so determined to record an album? How did you finance it?

Adrian: It just seemed like that was what you did if you were a musician in the 1960s. I have a vague recollection that I discovered that Paul Simon made his first album when he was 16, and that definitely gave me a target to achieve the same! Wrekin College Arts society generously gave us some money to do the recording. The figure I have in my mind is £30, and I believe that covered three hours of studio time, although it’s all very hazy and I may be wrong!

Were you both at school when it was recorded?

Adrian: Not quite – we recorded the album in the succeeding summer holidays.

Where was the album recorded?

Adrian: In Hollick & Taylor’s studio somewhere in the suburbs of Birmingham, maybe Handsworth

What was the studio like? How long did you have to record it?

Adrian: I have a vague memory of a typical suburban house in a typical leafy suburban street. More than that I just don’t recall, apart from the fact that there was a control-room separate from the “studio” room, and it took us a few goes to get used to the whole red-light communication mechanism. We’d do a quick run-through of each song for the engineer to get the levels right, then the red light would come on and we would immediately forget the words, who played which part etc. I think we had three hours and we did most of the songs in one or two takes, despite mounting panic over whether we would actually manage to complete the whole thing within the allotted time.

Did you have enough material for a full album?

Adrian: Yes and no. We thought we had, but we hadn’t rehearsed well enough since we’d been distracted by the inconvenience of A-levels a month or so previously, followed by the Apollo 11 moon landing. We discovered that while we could “wing-it” when live on stage, any slight error or hesitation in the studio would result in the red light going off and having to start again. While we could just about get through some of the pre-take practices, the red light became a Pavlovian signal to immediately self-destruct. So we recorded some of the covers we were used to just to calm our nerves, and ended up having to use those takes because we just couldn’t get the original material right.

‘Samantha Carol Fragments’ has an ISB reference in the lyrics (“Be glad for the song has no ending”). Where had you heard this? The ISB film and album of the same name were released after you recorded the album weren’t they?

Adrian: The “fragments” are two parts of an eight-part poem set to music. The poem (included in the book) begins with a quote from the poem “The Head” by Robin Williamson, which was included with the Wee Tam & The Big Huge double album, released in 1968, and the quotation reappears three times in the whole poem. If I’d known that the Incredible String Band were going to go on and use the same quote as the title of a film and another album two years later, I would never have used it in the first place! It is properly credited in the poetry booklet though.

How had you collaborated with others on the lyrics?

Adrian: I started writing music probably in 1967 or 68, when my English teacher suggested that I set a Robert Burns poem, Sodger Laddie, and a John Donne poem, Song, to music for one of the Arts Society productions. To my surprise it came relatively easily, and I then moved on to setting my own poems and the poems of my friends to music. I often found it easier to use my friends’ poems than my own for some unknown reason. It was quite a while later that I finally got to doing words and music together.

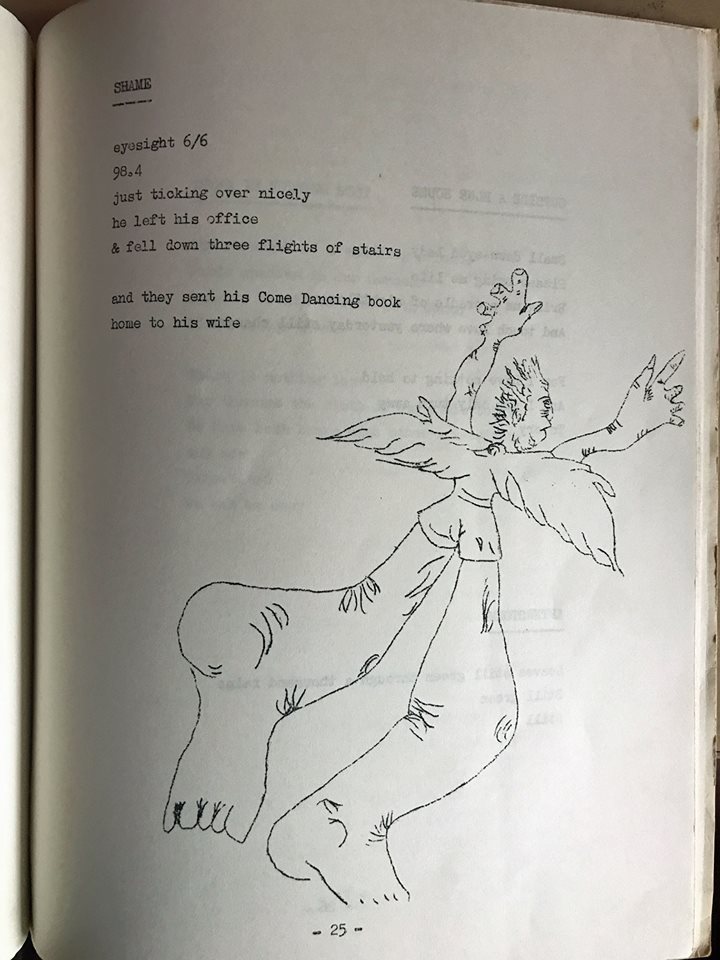

Can you tell me a bit more about the poetry book that came with the album?

Adrian: The school Arts Society produced a poetry magazine, Peccadillo, every year, and I and a few friends who became quite close had been contributing to it throughout our years at school. It seemed that most albums of the period included lyric sheets, and since all the lyrics of the songs on the album were originally poems before they became songs, it seemed like a good idea at the time to include a collection of all the poems with the album. That quickly developed into a bigger project, which finally became a collection of 30-odd poems by me, Jim Nock, Chris Mears, Danny Gibbs and Rob Housden. Jim was an accomplished artist, and so we put some of his illustrations in the book as well, along with a few others, although the Roneo stencil technology, which was all that we had available to use, meant that the quality of reproduction was outstandingly poor.

Why did you choose the title ‘Satori’?

Adrian: It was the 1960s and as it says on the last page of the poetry booklet:

“by meditation and bodily training

one may attain satori, a sudden

illumination and enlightenment on

the nature of the self and of the

emptiness of which all things are

manifestations”

Obvious!

How many albums did you press and what happened to them? Did you send any to record companies?

Adrian: 75 I think. They were all sold and have scattered to wherever they are now. No, we didn’t send any to record companies, and in retrospect I can’t understand why not. Maybe we were worried about having to pay royalties on the covers!

How long did you play with Roger? Did you record anything else?

Adrian: Probably for two years while at school and briefly afterwards. We then went our separate ways and our paths rarely crossed for long enough to keep the momentum going.

How many copies of the album survive now?

Adrian: I have no idea, although I know of 4 copies, maybe 5.

Can you tell me about the music you made with Pete Thomas?

Adrian: Since I was 13 years old, I’ve played music of all sorts with a friend of mine, Pete Thomas. He’s a natural musician who can play anything, and we grew up heavily influenced by ISB etc, writing our own stuff at the same time as moving through straight folk to bluegrass via the Holy Modal Rounders and Mike Hurley – another big influence. Pete’s from Hereford, I’m from Swansea, and when I was at boarding school in Shropshire, Pete was at boarding school elsewhere. So the partnership between Roger Latham and me was really a result of us being at the same school together and when we weren’t at school, most of my musical adventures happened with Pete, and involved a lot of travelling back and forth between Hereford and Swansea. When we left school, that was pretty much the end of Benjamin Delaney Lion, but Pete and I still play together from time to time, and we still bill ourselves as Tay Bridge Disaster, although we have performed under many guises over the years, including a period as Blasted Oak, and also Die Flederhosenbrüder (The Flying Trouser Brothers).

Tell me more about Tay Bridge Disaster.

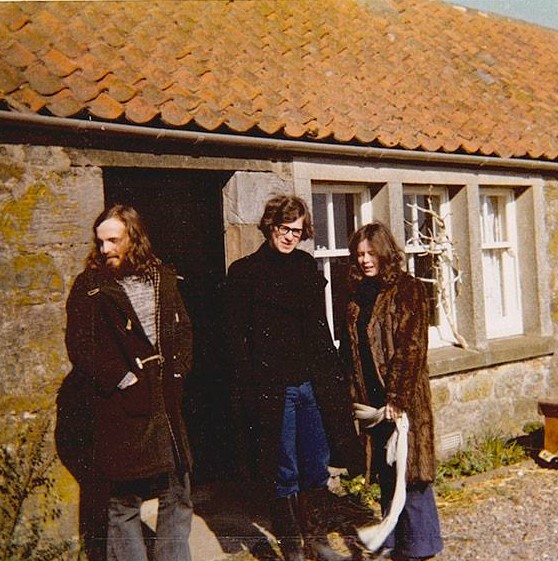

Adrian: I was at university in St Andrews from 1970 to 1974, and while I played regularly solo at many of the folk clubs up there, Pete would come up and we would play as an unnamed duo every so often. As it happened we entered a “write a folk song competition” while I was up there. I did a version for the qualifying heat as an unaccompanied duo with another friend who I roped in, as Pete was in London and when we got through to the final, Pete came up and we did it as a trio in a Glasgow pub somewhere. We needed a name, and since I was living in Fife and close to the Tay, we picked “Tay Bridge Disaster” out of the air!

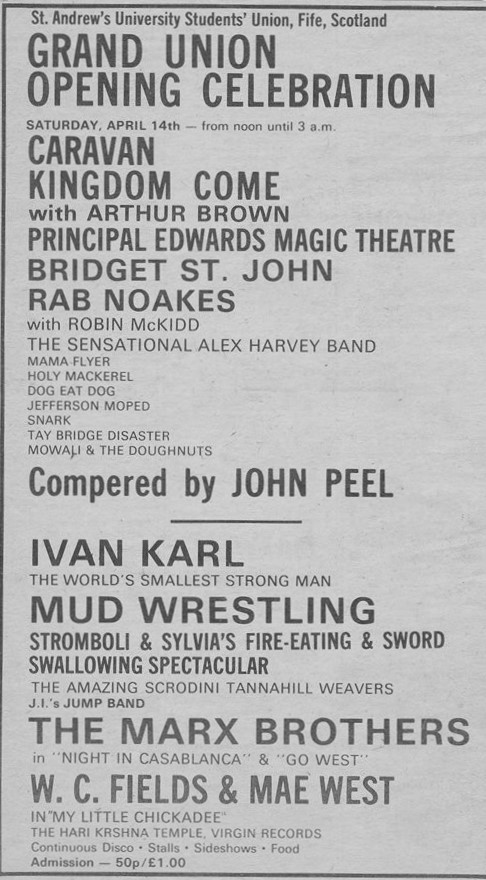

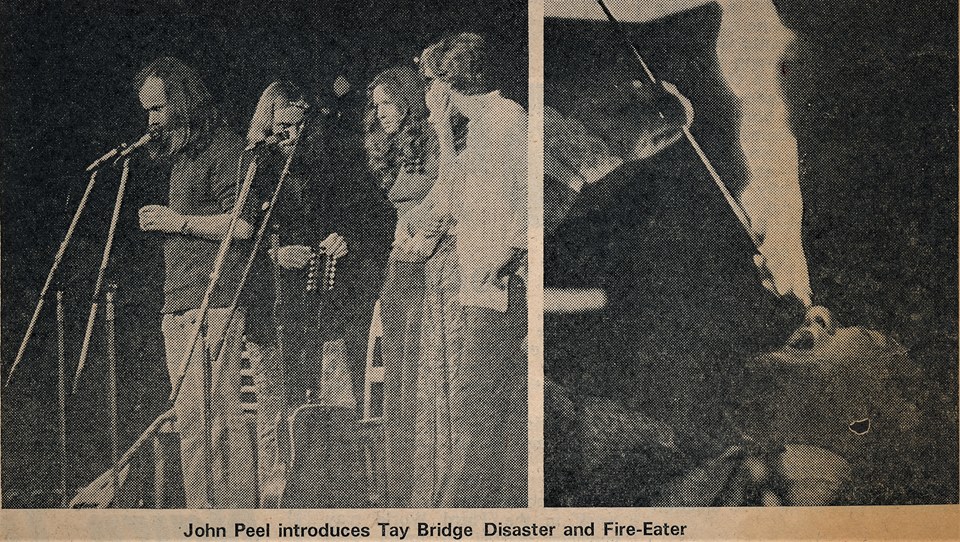

At the same time, I was sharing a house with the Entertainments Convener for the Students Union, and he had arranged a big 24-hour gig to celebrate the opening of a new Students Union building. This featured many bands, including Principal Edwards Magic Theatre, Arthur Brown’s Kingdom Come, Bridget St John, and amongst a host of supporting acts, Tay Bridge Disaster.

Did you record anything?

Adrian: There’s a cassette tape we did as “Blasted Oak”, featuring another friend, Dave Warnes, on voice and guitar from time to time. Pete still has a large archive of our music on 4-track tapes, but they’re Ampex tapes and they have a habit of dropping their magnetic coating after being left untouched for 40 years or so, so they have to be “baked” before we can risk playing them again.

Have you continued to play since?

Adrian: I have, more so than Roger, although he continues to sing with a local choir. I played in folk clubs, intermittently but pretty much continuously, since the days of the Adelphi in Swansea and ended up running Penarth Folk/Blues club for 8 years in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and have been co-hosting Penarth Acoustic Club for the last 3 years.

The album remains unavailable on reissue though hopefully some enterprising label can work out a deal and the greater public can experience Benjamin Delaney Lion’s magical acid-folk sound. The six originals cover a variety of moods, from the pensive ‘I Alone’ with its melancholic chord shift, to the languid warmth of ‘Midnight People’. The aforementioned ‘Samantha Carol Fragments’ features a delicate vocal harmony between Roger and Adrian and a stark arrangement coupled with a mystical lyric. “I’ve been no more than footsteps for so long” open the lyrics to ‘Oldman’, which again varies the mood with an impressionistic acoustic guitar section in its centre. ‘There is Nothing Lost’ is a shorter track with words from friend Jim Nock, while Chris Mears’ Sufi-esque lyric is the highlight of ‘In the Knowledge of My Soul’, which features an eastern influence in the guitar work. The four ISB songs are ‘Dandelion Blues’, ‘Painting Box’, ‘Log Cabin Home In the Sky’ and ‘Ducks on a Pond’, the latter closing the album with a celebratory kazoo solo, faithful to the original.

Their version of Donovan’s ‘Hampstead Incident’ completes the tracks – a superb reading capturing the elegant mystique of the original. It remains a superb document of a hopeful time, full of wishful dreaming and teenage artistry and one hopes it can be exposed to a greater audience in the fullness of time.

– Austin Matthews

Read the article re The Satori album by Benjamin Delaney Lion. Adrian mentioned he knows of 4 possibly 5 left. I have one, the song titles are hand written on the label (without the booklet) so that makes 6.