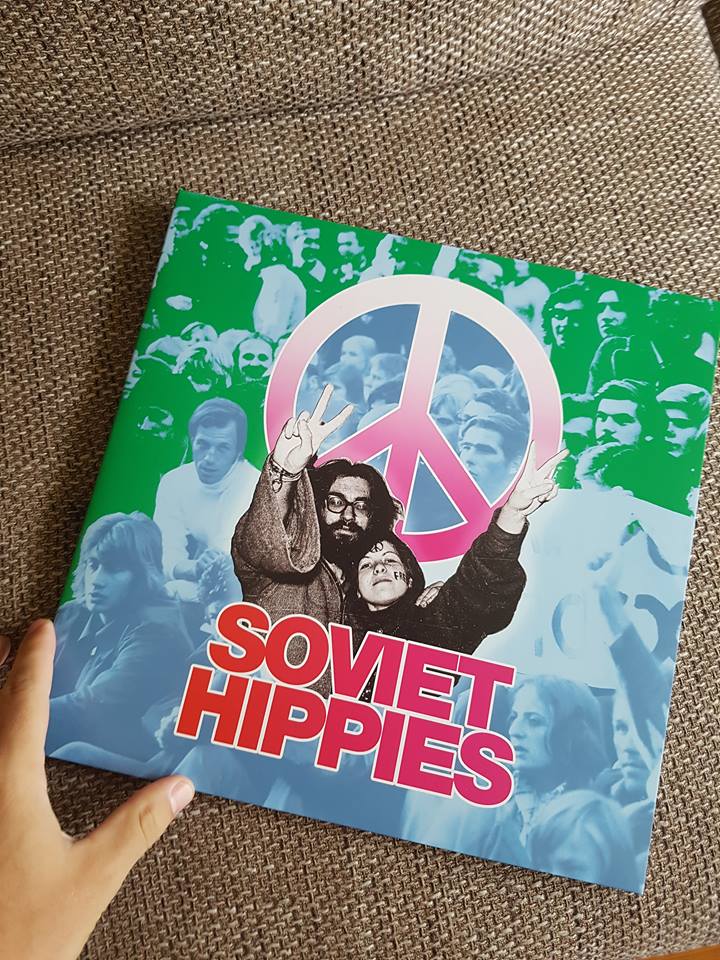

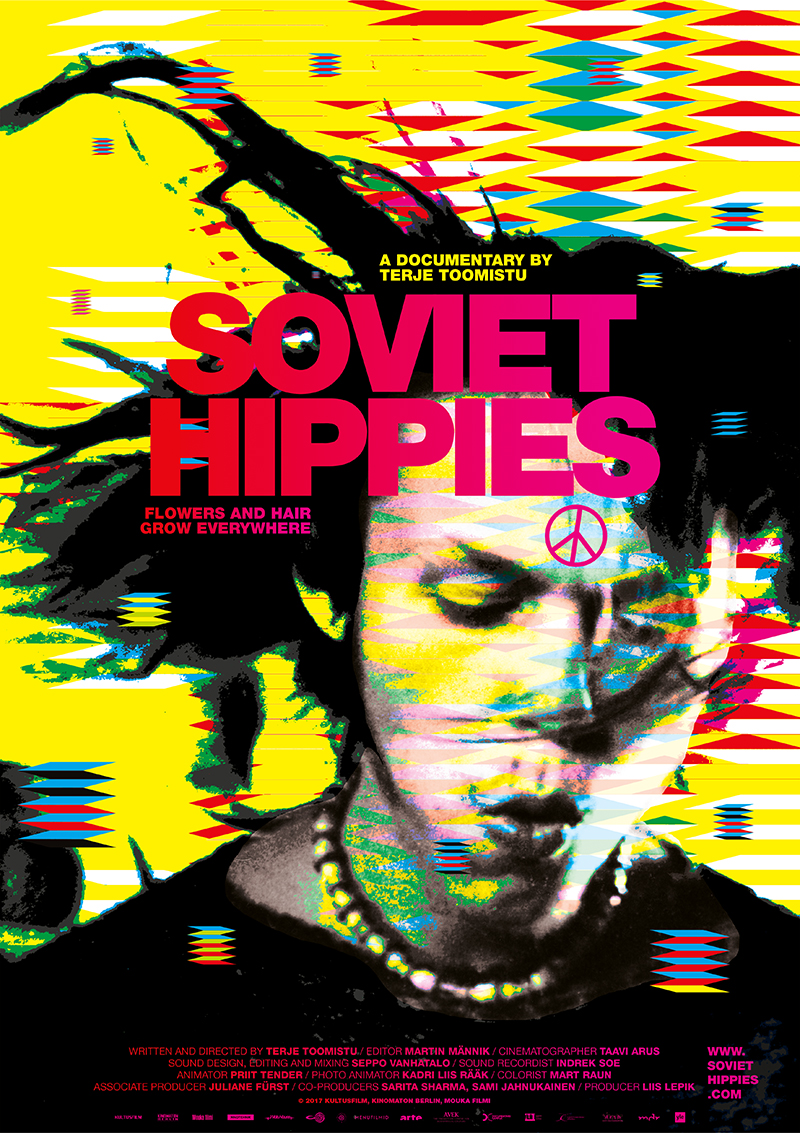

Soviet Hippies

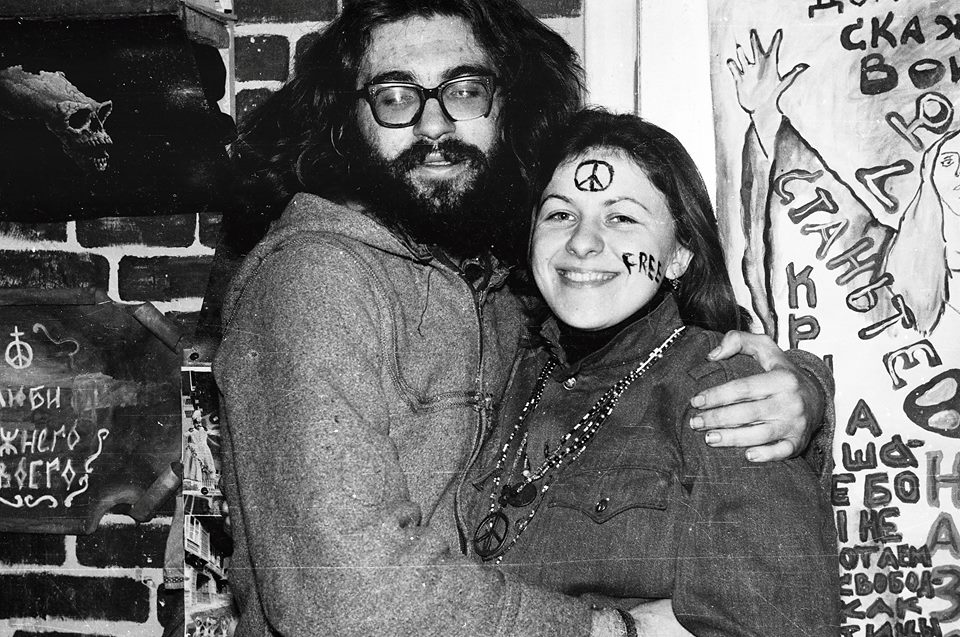

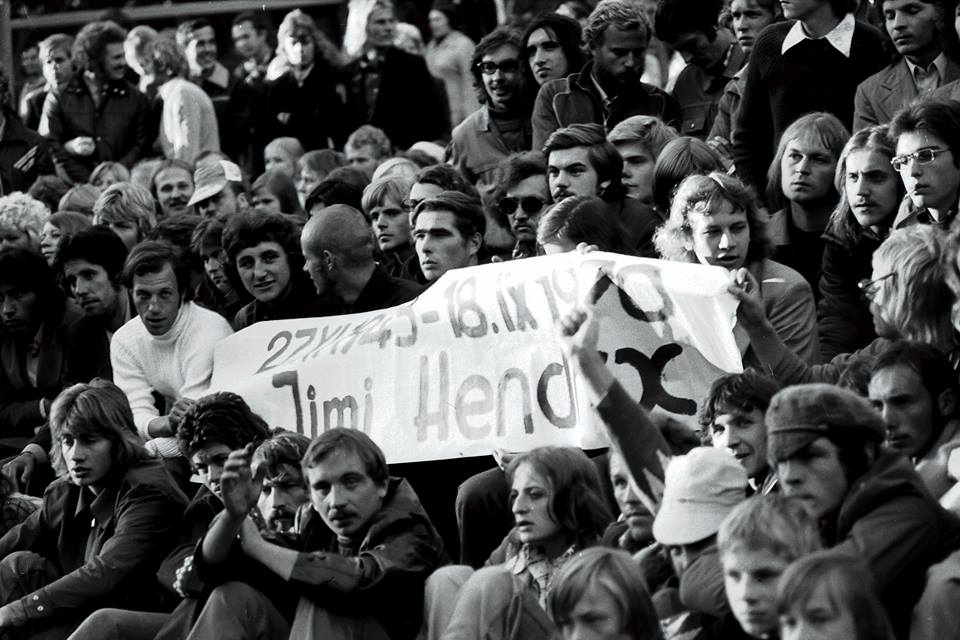

The hippie movement that captivated hundreds of thousands of young people in the West had a profound impact on the other side of the Iron Curtain. Within the Soviet system, a colorful crowd of artists, musicians, freaks, vagabonds and other long-haired drop-outs created their own system, which connected those who believed in peace, love, and freedom for their bodies and souls.

Interview with Terje Toomistu Cece (October, 2017)

Would you like to talk a bit about your background?

My journey to documentary filmmaking went in spirals. During my teenage years I was a student activist, journalist for a local newspaper, but I also organized underground music events in the small town I grew up in central Estonia. My heart was beating with arts, history, music, and writing, but I was somehow also really good in maths and psychics, went to competitions and scored maximum points at the national graduation exam. So somehow I ended up doing my first degree in economics. At the same time I started traveling extensively and writing about it. After spending some time in India, Cuba, Oman, Kenya, Benin, and half a year of a life changing experience in South America – what I have later come to regard as my own hippie era – I realized that wherever I went I was most interested in the local perceptions of reality. Hence, I was traveling like a wannabe anthropologist. So I continued for master degrees in both, communication studies and anthropology, and I’m currently working on my PhD in anthropology.

To a large degree, documentary film for me is doing anthropology or making anthropological knowledge visual and graspable for wider audience. But film-making is also a creative and collaborative craft. So I guess there’s an artist in me that eager to work with visual material and that has perhaps found its language precisely in documentary.

In 2011, I collaborated with Estonian artist Kiwa and we made an indie activist documentary about Indonesian transgender community, the film is called Wariazone. But nevertheless, Soviet Hippies is often considered my debut. Recently I also made a short experimental documentary entitled Archaelogy Of Ayahuasca, which takes a critical look at the knowledge production around the indigenous South American master plant during the current ayahuasca boom in Peru.

How did you first get interested in alternative culture?

I’ve been a bit rebellious kid since early on. Something totally stroke me about the power of resistance and the boost of imagination in the 1960s youth movements already during my teenage. I’ve always enjoyed psychedelic rock music or some trippy doom and noise, and the aesthetics as well as ethics of psychedelia.

Recently after finishing the film I have realised that perhaps some painful experiences from the early sensitive time of my life have left a mark on me, which subconsciously haunted me in making this film. During late 1990s in the town Paide where I grew up there used to be a kind of opposition, a street war, between the youth who were considered the hairy ones – my bohemian, arty, music-making friends – and the bald-headed ones, who today are rendered as douchebags. It’s not hard to guess which of them were the violent ones and which tried to hold on to the pacifist ideas.

This film for me is perhaps a way to do some justice to these violent patterns that haunted my teenage years and I’m sure they sound familiar to many. If the problem today is not the hair, it might as well be the skin color, gender identity or sexual orientation.

What was the process of getting in touch with all the people who were part of the documentary?

At the beginning, the process was very personal of course. The first person I met with curiosity towards the history of this subculture was Vladimir Wiedemann, who has published some books in Estonian and Russian on his hippie memoirs. His book entitled The School Of Magicians just blew my mind. Just imagine – having grown up in the post-socialist Estonia, where the soviet era was framed as the dark times with nothing good to remember, then this book totally shifted my understanding of the late Soviet era. I learnt about underground spiritualist movements, the guru Sri Rama Michael Tamm, youth resistance and crazy experimentation with available drugs. It was precisely his book that gave me the first kick into this research and who would have known that it would be six years of intense work ahead!

Vladimir Wiedemann took me to Aare, who can be now regarded as the main protagonist of the film. I was moved by his warmth and intelligence as well as his personal story of being one of the first hippies in Tallinn and a great traveler. We became friends. Several years later after meeting many charismatic characters and having heard great many stories, I returned to Aare in the editing room. I realized that his personal drama of being imprisoned by his body that is ill is somehow in reference with the collective story of the Soviet hippies who were trapped by the society, which was ill.

The extensive research led me to many amazing people I was fortunate to get to know. I was also advised by my research advisors Juliane Fürst and Irina Gordeyeva. Unfortunately it was impossible to budget interviews with all of them, and actually several interviews we made eventually didn’t end up in the movie. These were the difficult choices in the editing process, that took altogether about 1,5 years.

Was it difficult to get the story together?

During the documentary development there were several options that passed my mind and our brainstorming sessions with my producer Liis Lepik. As it’s often the case, we eventually ended up almost where we started. After the film was already cut together, Liis found some very early script that I had written and forgotten about it long ago and to her surprise, this was pretty much the story we got now, although in between we had been miles away.

Because nobody still knows much about the hippie movement in Soviet Union, I always wanted to focus on the story of pop culture, history and power relations, while we were also testing a more character driven take.

The key challenge was about tying together the historical story with the characters in present times. During the film, the main protagonists from Tallinn take a road journey to Russia, seeking their old friends and joining the annual hippie gathering on the 1st June in Moscow. But then there’s the complex history! And different mediums. I wanted to illustrate the Soviet psychedelic culture with the use of animations from that era, as animation was one of the very few locations where psychedelic sensitivity was allowed to be expressed (animation was intended for children, right). In collaboration with Estonian recognized animation artist Priit Tender we also created a new animation to deepen the more psychedelic aspects of the story.

“Everybody was saying to us that there were no hippies in the Soviet Union, maybe only a few eccentric individuals, but a movement?”

Because of the complex sociocultural context, different shooting locations, variety of characters, and the dense material from the past and present in different mediums, it was a very difficult film to edit. My brave editor Martin Männik and I had to sit with the project long days, often over weekends, for almost 1,5 years. I would lie if I said we were not totally exhausted towards the end of it, but you could hardly make it with less time and energy with that kind of complex research based movie.

You did a wonderful job. There wasn’t much known about this counterculture movement happening in Soviet Union.

Thanks, and indeed! That’s why I basically had to start with ethnological research from scratch, as there was hardly anything known about the movement. The Soviet official discourse and media, of course, neglected the existence of it, so most people that lived in the Soviet Union also didn’t know that there were hippies. Thus it was essential to meet the survivors (indeed, most of them are gone by now) and interview them, before I was even able to envision the storyline. Now we can laugh about it, but I remember when we were editing our first trailer for fundraising, my producer insisted that someone should say it out loud that there were hippies! Because even when the people of the funding committee had lived in the Soviet era, they didn’t believe that we had a story! Everybody was saying to us that there were no hippies in the Soviet Union, maybe only a few eccentric individuals, but a movement? Forget about it!

I also find the music fascinating. The film features 100% music from Soviet underground. For me, this is also an archive that is important to bring out for wider audiences. Lots of bands that are heard in the movie are from Soviet Estonia, as Estonia had the most vivid music scene, especially in early 1970s. The first psychedelic rock band from Soviet Union was from Tallinn, called Keldriline Heli which translates as the ‘basement sound.’ They were students practicing in the basement of today’s Tallinn University of Technology. Some people still remember the profound experiences from their concerts, until one of them was perhaps too good and the band was soon banned from performing. Also the first progressive rock band in Soviet Union was from Estonia, led by talented musician and today a renowned composer Sven Grünberg. His song “Valged hommikud” (“Bright Mornings”) is one of my very favorites of all times.

It was more complicated to find great tracks from Soviet Russia, as they had worse recording possibilities. With some research advice, I managed to dig out quite a few forgotten pearls, like the song of the final episode by Zhar-Ptitsa or the hidden treasures of a brilliant Russian musician Yuri Morozov.

“When for example president Nixon visited Moscow in 1972 or during the Olympics 1980, the streets were literally cleaned from hippies and other outsiders.”

Somehow you managed to locate absolutely incredible footage from the 1970s.

This was one of the biggest challenge. Because in the eyes of the Soviet authorities, there were no hippies in Soviet Union. When for example president Nixon visited Moscow in 1972 or during the Olympics 1980, the streets were literally cleaned from hippies and other outsiders. The soviets were trying hard to combat this ideological Cold War battle. So that’s why there is no official records of the hippies and I had to look into private archives.

At the beginning we didn’t believe we are able to find much. First of all, very few people had a camera. Secondly, the camera was often the first thing that the KGB would take away from the hippies. In a way, the rise of the social media has revitalized the relationships between the Soviet hippie Sistema people and fortunately this helped me too.

We had already produced an exhibition for Estonian National Museum in 2013, which made me somewhat known in the community. After putting the word out there in social media about the film-making, there was long silence, until I received a message: there’s a box full of archives in Moscow that can only be handed over in person. So I had to take the train to Moscow, meet someone over a kitchen table, drink tea, and carry a heavy box with some tapes back to Estonia, where we scanned most of them in our film archive. The person who had collected this material was a hippie lady herself, but had to flee the country for some shady political reasons. So a couple of miracles fortunately happened. These unseen archives of course give an excellent contribution to the fragmented and layered language that is developed in the film.

How long was the filming process?

As I already mentioned, we had the research phase first when we conducted video interviews with about 15 individuals in Estonia only. Based on that material I co-curated a traveling exhibition on the topic that is still on the move, planned for Liverpool in 2018 and hopefully also Leipzig.

Later we were shooting more in Tallinn, Moscow, and Lviv in Ukraine. The most challenging was the road trip to Moscow, lasting almost two weeks and being a true adventure, a film in the film and certainly yet another wicked film when the camera was not rolling. We worked on this together with the protagonists, planning the journey and following their ideas, but it was of course very complicated. They are not anymore some 20-year-old kids who can sleep wherever and travel however, while I also couldn’t have accepted to be a kind of tour leader who provides everything. So it required a lot of trust and collaboration.

Our director of photography Taavi Arus, sound recordist Indrek Soe and me joined the journey full time, producer Liis Lepik was with us part time. We also picked up hitch-hikers, met some fans of Vladimir Wiedemann who joined us for a day. Lyuba and one of our protagonist Poja’s son form st. Petersburg decided to spontaneously join us for Moscow. We ended up in a hippie wedding in Riga, Latvia. So the journey was very colorful in itself, but only some key moments ended up in the movie. But documentary film-making is always more about saying no to the material than saying yes.

When was the premiere?

We had the home premiere in Estonia on the 1st June, which was a great date as the 1st of June is still celebrated as the day of the hippies in Russia and some other post-socialist states. It also links back to the event from 1971 Moscow when thousands of hippies got arrested on their very first openly political manifestation. This was the event that was designed as a trap for the hairy ones, and which as a result pushed the movement deep underground. So we were lucky to come out with the film on that highly meaningful day. With the home premiere we also announced the beginning of Summer Of Love in Estonia and for the world. Namely, 2017 marks 50 year since the peak of the western hippie movement and I think it’s an excellent pretext to think back at the legacy of the 1960s youth movement. While the sociopolitical context has changed almost 180 degrees for the Soviet hippies, the struggle is still pretty much the same. It’s still very crucial to recognize the importance of pacifism as an ideal and practice.

We had the Finnish premiere in Helsinki at the Love and Anarchy film festival in September and as I’m writing this, my body is floating in space on my way to Sao Paolo in Brazil for the film’s international premiere. The European premiere takes place soon after in DOK Leipzig, where the film is scheduled for November 1 and 2. Sounds like a good kick start for the world travels of the film and I hope this journey will be long and wild. You can follow the film’s journey on the Facebook page Soviet Hippies.

– Klemen Breznikar

Soviet Hippies Official Website

Soviet Hippies Facebook

Soviet Hippies Instagram

Soviet Hippies Twitter

Soviet Hippies Bandcamp

Thanks for sharing Klemen, it's fascinating and looks worth checking out.