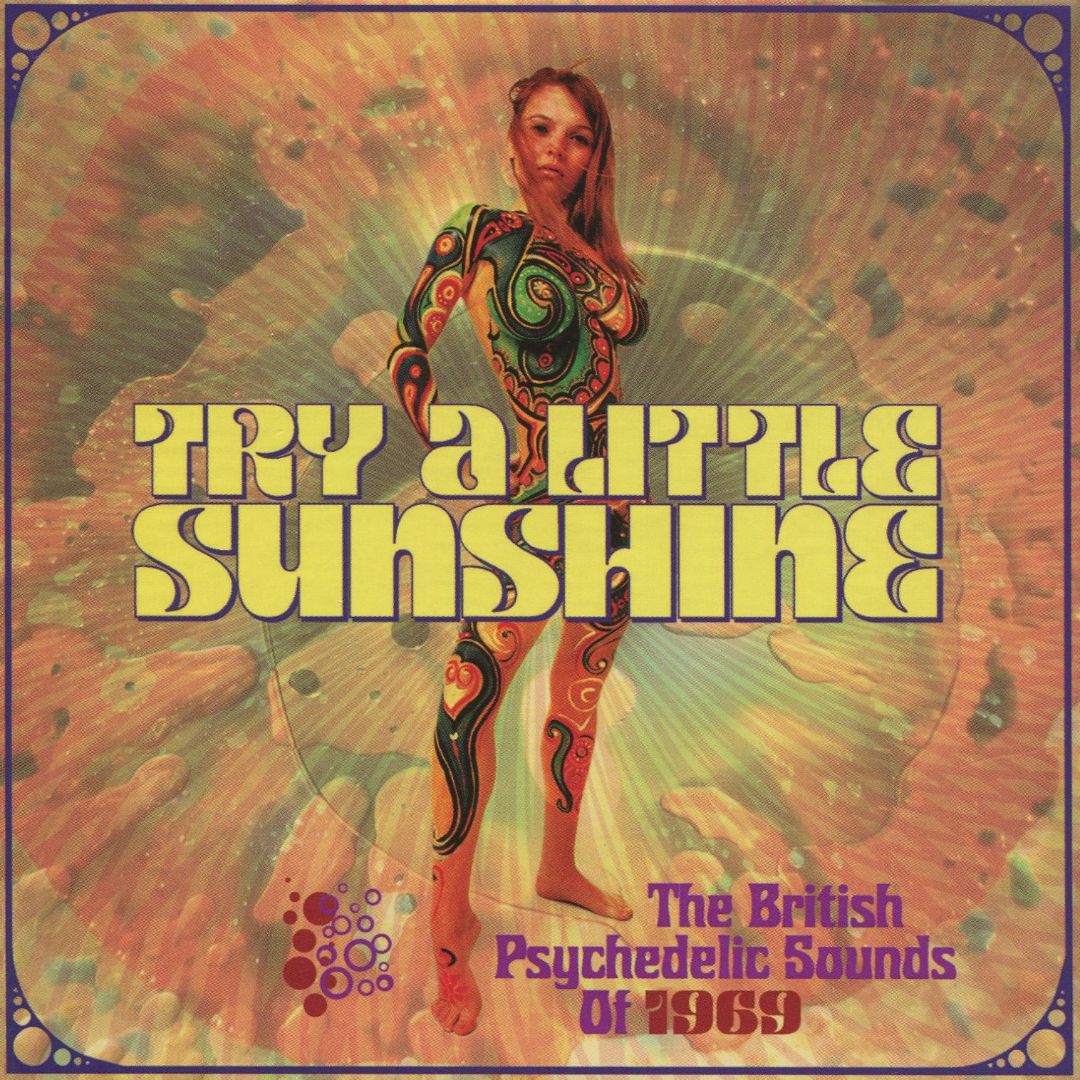

‘Try A Little Sunshine’ (2018)

The popular interpretation of 1969’s musical landscape evokes a number of epochal keystones of recent collective memory. Woodstock, the Stones in Hyde Park and the Beatles performing on the rooftop at Savile Row dominate much of the pop cultural fascination surrounding the final year of this tumultuous decade.

Retroactively, this appears like a climax of sorts to the psychedelic counterculture at large, a cathartic release of the seismic pressure building since 1967’s famed Summer of Love. Therefore, it’s surprising to learn that at the time, psychedelia was believed to be an already dead fad. At the Apple offices in London on September 19th, 1969, in an interview with Paul McCartney regarding the pending release of the Beatles’ eleventh album, ‘Abbey Road’, the BBC’s David Wigg provided a contemporary voice to this view. “Why did you use the lyric, ‘Turn me on’ and ‘blow my mind’? I rather felt that sounded a bit passé in 1969, cuz it’s been used so much in the past”.

The latest instalment of Grapefruit Record’s acclaimed late 1960’s Brit-Psych series, ‘Try A Little Sunshine: The British Psychedelic Sounds of 1969’ challenges the view that the soundtrack to the final year of the Sixties was all rootsy jamming by Creedence Clearwater Revival or ploddingly puritanical 12 bar blues boom rehashes. As David Wells writes in the accompanying booklet, “if psychedelia was dead, clearly nobody had told the likes of the Factory, Fleur de Lys or Jason Crest”.

Packaged in a clamshell box and coming with a detailed 44 page booklet, each of the 3 discs that make up this fascinating facsimile of 1969 is housed in it’s own paper sleeve replete with individual pop-art psychedelic designs. The standard Grapefruit attention to detail is apparent in the selections that make up the tracklist. Cult classics like the shimmering, euphoric title track by Surrey teenage outfit the Factory rub shoulders with B sides and album cuts by key acts such as the Move and Procol Harum, groups that achieved some modicum of radio airplay but not commercial success such as the Spectrum, Harmony Grass and Fortes Mentum through to complete obscurities, some of which are released here for the first time. Take, for instance, ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ by Peter Howell & John Ferdinando, a track which originally was only intended to soundtrack an amateur local production of ‘Alice Through the Looking Glass’. One of the real gems here is a previously unreleased cover of the Kinks’ ‘Mindless Child of Motherhood’ by former Turquoise drummer Ewan Stephens in which the Dave Davies penned track is decorated to the point of reinvention with soaring prog-guitar fanfares and heavily reverberated vocals.

The subliminal theme throughout is one of missed opportunities and unfair consumer negligence. Take the Pretty Things, for instance. Their 1968 concept album ‘S.F Sorrow’ is by all accounts one of the best of the entire psych oeuvre, yet it sank without trace, overshadowed by higher profile releases by the Beatles and the Rolling Stones within the same week of it’s release. They are represented here with the previously unreleased ‘You Might Even Say’, with the French millionaire playboy Phillipe DeBarge on lead vocals. That this track- which has a pronounced debt to ‘Forever Changes’ era Love in composition- originated from an album DeBarge commissioned the Pretty Things to record with the intention of distributing it solely amongst his immediate social circle showcases just how unfair their lot was. Furthermore, the sheer pace of musical innovation saw several genuine pioneers left behind by the time they got around to recording their debuts. For instance, the Mooche (represented here with the chugging keyboard led ‘Seen Through a Light’) supported Soft Machine in a February 1967 ‘psychedelic freak out’ that predated the release of Sgt Pepper by four months and frames them at the very forefront of the entire movement. Barclay James Harvest’s blissed out ‘Brother Thrush’ would have sounded right at home on a Moody Blues album, but by the time it saw it’s June ‘69 release, progressive music had reached far more experimental heights. The Consortium managed to reach the UK Top 30 in 1969 with the saccharine ‘All The Love In The World’, yet the B-side to their flop followup, which is included in the tracklist, could well be a metaphor for the fortunes of some 90% of the acts compiled here- ‘The Day The Train Never Came’.

That said, we also get a glimpse into the early careers of musicians who would go on to attain commercial and critical success in the near future Future King Crimson and ELP virtusoso Greg Lake can be heard amidst the anthemic crescendo of Shy Limb’s ‘Reputation’. John Kongos, who would go on to score solo hits in the early 70’s, was a member of Scrugg who contribute the “schizoid singalong romp” of ‘Only George’. Ralph McTell of future ‘Streets of London’ fame also pitches in, providing the breezy sunny pop hit that never was, ‘Summer Come Along’.

It’s just as interesting to chart the concessions made by musicians to the zeitgeist of the divergent year that was 1969. For some, such as Strawberry Jam and Homer’s Knods, that meant going bubblegum. Let us not forget that the Archies’ ‘Sugar Sugar’ was the greatest hit of the year- music was still a commodity to be sold, after all, and bubblegum acts such as the Monkees and the Lemon Pipers attained enormous success in the late 60’s. Bubblegum is a faintly derogatory and unfair label to apply here; after all, these well constructed pop songs share much musical D.N.A with the childish Victoriana of earlier British psychedelia.

The other direction in this, the year of Led Zeppelin’s debut, was to go ‘heavy’. Psych svengali John du Cann, veteran of the seminal freakbeat group the Attack and the blissed out paisley pop of the Five Day Week Straw People, went on to form Andromeda, a ‘power trio’ in the same vein as Cream and the Jimi Hendrix Experience. Their track, ‘Day of the Change’, is featured on Disc 3 and is an interesting transitional piece- the melodicism of well crafted mod pop remains intact, there is a recurrent Indian style guitar motif that recalls earlier forays by the Yardbirds, but there is a definite heaviness in the musicianship that points the listener firmly in the direction of the hard rock of the 70’s. The pursuit of approval from the underground led to plenty of worthy recordings being shelved, such as Tuesday’s Children’s previously unreleased harpsichord led ‘Doubtful Nellie’. Given that the group were on the cusp of transitioning into Czar, this track was left on the cutting room floor after being judged “unrepresentative of the band’s new, heavier direction”. Even the darlings of the underground’s gritty underbelly, the proto-punk and ever anarchic Deviants, were aware of this new trend and contributed with ‘Death of a Dream Machine’, penned by guitarist Paul Rudolph. “They wanted to be a kind of Led Zeppelin guitar band”, bandleader Mick Farren recounts with regards to this new direction, “which I didn’t really think they had the chops for”.

A factor of British psychedelia’s longevity is the sheer diversity of the subject matter involved and in this respect, ‘Try a Little Sunshine’ does not disappoint. The Orange Machine provide a “tribute to the first murderer to be apprehended by the use of wireless telegraphy” in their Tomorrow influenced opus ‘Dr Crippen’s Waiting Room’. The Onyx eulogise the exploits of a Mongolian warrior king in the Kaleidoscope-esque ‘Tamaris Khan’. Fat Mattress weave the “age old story of an extra terrestrial visiting Earth and forming an attachment to a petrol pump” in ‘Petrol Pump Assistant’. The sea shanty-esque ‘River Boat Queen’ by Audience evokes the era’s cultural fascination with Bonnie & Clyde and other such criminals through the character of an antagonistic female pirate. And so on and so forth. As has come to be the norm with Grapefruit’s compilations, the sequencing of the discs is a master stroke in and of itself. In spite of the disparate range of material here- which even includes some folkier iterations of psychedelia from Marc Brierly and the Judy Dyble vehicle Trader Horne- the flow never feels forced, nor does it threaten the listener in the slightest with boredom.

The set also captures the moment when lysergic music escaped the confines of Swinging London’s exclusionary trendy clubs and permeated throughout the entirety of the British isles. Over the course of ‘Try A Little Sunshine’, the geographical spread of the psychedelic movement is charted- we hear from “the Scottish Beatles”, the Beatstalkers, with the effervescent cut ‘Little Boy’; the mellotron-soaked prog nugget ‘Little Bird’ comes courtesy of Welsh outfit the Eyes of Blue (a group who nearly changed their name to ‘Bloody Welsh’), and “Ireland’s answer to the Beach Boys”, the Freshmen, are represented with the whimsical ‘Mr Beverly’s Heavy Days’. If psychedelia was falling out of favour in the swinging capital, then it was certainly catching on elsewhere.

Before long, the very same provincials who had been throwing their pints of lager over the Crazy World of Arthur Brown and Pink Floyd in the summer of 1967 were getting involved, abandoning the Motown standards which had previously fuelled their live sets. In one anecdote within the lavish booklet, it is recalled how the New Formula “abruptly changed musical direction after being bottled off by the peace and love brigade at the Woburn Music Festival in July 1968”, the fruits of their new psych direction making their way onto this compilation.

Such interesting tidbits of information are frequent within these immaculately researched liner notes- who knew that the Gregorian chants which augment Jason Crest’s bad trip freakout, ‘Black Mass’, were provided by a hastily recruited taxi driver and a cleaner, amongst others, who recorded their part “in the gents’ toilets, because it had the right kind of acoustics”? Certainly, there are tracks here which will be familiar to the die-hard psych fan, but it is such insight to the recording process that reframes these classics through the context they provide.

‘Black Mass’, with it’s doomy backwards effects and babbling, histrionic vocals, wasn’t alone in reflecting a growing dark edge to the increasingly visceral British psychedelic scene. Writing on the Wall, protégés of the short lived Middle Earth record label, lead off disc 2 with the hard charging ‘Child On A Crossing’. The dissonance of the echoed leading riff is as disorientating as the reverb in the ‘chorus’ (if you could call it such), with the harsh vocals recalling Roger Chapman of Family. Writing on the Wall witnessed the degeneration of the underground themselves first-hand, performing frequently at counterculturally inclined venues. The encroaching heaviness sought by contemporaries such as the Gun and the Edgar Broughton Band (not included in this set) was in part an attempt to express the shift from ‘soft’ drugs like marijuana and LSD to drugs such as heroin and other opiates. Jake Scott of Writing on the Wall recalls “all nighter gigs” at the Middle Earth club where it wasn’t uncommon to find “the toilets were full of needles”. 1969 saw a high profile drug casualty in Brian Jones, and the growing drug problem cracked the cheerful facade of British psychedelia. Even comparatively straightforward, radio friendly pop tracks such as the Tapestry’s manic raver ‘Who Wants Happiness’ carry the ominous premonition of a Britain about to swing itself into a cardiac arrest, of a Cheshire Cat with an increasingly strained, hard to maintain grin. 1969 was a hard year to be one of Britain’s ‘Beautiful People’. The simultaneous rise of a working class skinhead movement which openly attacked and vilified the middle class hippies, the closure of the Middle Earth club, the violent eviction of the London Street commune from the ‘Hippiedilly’ squat by London police, not to mention the exploits across the pond of a certain Charles Manson and his ‘Family’ meant that the counterculture backlash was just over the horizon.

It was this element of encroaching danger that no doubt influenced the nostalgia of Second Hand’s ‘Good ‘Ol ‘59 (We Are Slowly Getting Older)’. Keyboardist Ken Elliott acknowledged a growing sense of disillusionment both within his group and in the counterculture as a whole, realising that “psychedelia was just the latest fad…. we were just young people in an ephemeral situation, hoping to enjoy it while it lasted”. The self awareness of this particular track is in line with another theme of this compilation- that of a party coming to end and a generation coming to terms with it’s own legacy. The genre of psychedelia is unique in that it was no longer truly sustainable on a widespread level when removed from the zeitgeist which spawned it, hence why the ‘golden age’ was so short lived and it largely died with the decade it originated in. The heady brew of postwar optimism, a sizeable and wealthy young middle class and open experimentation with drugs had provided the perfect incubation chamber for the escapist hedonism of the genre, which no longer had any creedence in the more hostile political climate of the early 70’s. Alfie Shepherd of the Angel Pavement, the band behind the first disc’s ebullient ‘Green Mello Hill’, summarises this phenomenon succinctly- “Nothing lasts forever. The whole magic thing of the Sixties and flower power, the hippie era, you can’t keep that sort of thing going. It just ran out of momentum.”

‘Try a Little Sunshine’ closes with a cut that epitomises many of the traits of the ill fated groups on this compilation, as well as wrestling with the disappointment and disillusionment which marked the ending of a decade renowned for it’s oscillating, dizzying optimism. The Cape Kennedy Construction Company, as with many other bands of this era, were the product of record industry opportunism, formed to cash in on that all pervading pop culture moment of 1969, the moon landing- issuing their single ‘The First Step on the Moon’ around a month after the event. The B-side, ‘Armageddon’, is what made the grade and closes off Grapefruit’s excursion into 1969 and puts a full stop on their entire late 60’s trilogy. Perhaps the weirdest track on the entire compilation- and that’s saying something- ‘Armageddon’ is an accidental masterpiece. The group’s lead singer John Carter stresses that “he was not involved in any way, shape or form with ‘Armageddon’ and assumes it was something concocted by the engineer and assorted studio hands purely for B-side purposes”. A pseudo demonic, heavily distorted voice seems to quote the Book of Revelations through thick reverb alongside a Procol Harum-esque organ line. It’s a mournful, almost funereal piece of music. When the reedy vocals pierce through the production, it’s as if the dying 1960’s themselves are personified, reflecting on the tumult of the psychedelic era. “I’ve seen love- but I’ve seen death… They blow us up, they burn us down”. What sounds like jet engines scream through the speakers, perhaps a comment on the omnipresence of the Vietnam War and the shadow it cast upon the hippie movement, fitting given that 1969 saw the famed exposure of the My Lai Massacre and a myriad of other gruesome atrocities. With the jets still echoing, the vocals return, repeating the nihilistic mantra of “born to lose”. That a quickly cobbled together cash-in act managed to construct an intelligently opaque statement on the decades’ end, a day-glo tombstone to an ending era, verifies Grapefruit’s intentions with these excellent collections. This isn’t just music to be enjoyed by the niche of obsessive music collectors- it’s an alternative soundtrack to one of the defining eras in modern history and an anthropological document of sizeable historical importance.

‘Try a Little Sunshine’ is yet another supreme, indisputable success by Grapefruit Records in that it achieves something all too uncommon in the compilation industry- it breathes new life into the music it compiles and forms a cohesive overview of the full range of a notoriously versatile genre and it’s place in history, from the drugged out anarchists in the Notting Hill Gate all the way through to the squeaky clean popsters exploiting a new trend to earn a quick payout. The reverence and respect with which the compilers show the material they showcase is made abundantly clear through the excellent remastering, the intensely researched notes within the booklet and the gorgeously ornate sleeve designs. At the end of Bruce Robinson’s cult classic ‘Withnail and I’, set at the fag-end of the 60’s, Mick Farren caricature Danny laments that “London is a country coming down from it’s trip. We are sixty days from the end of the decade, and there’s gonna be a lot of refugees. We’re about to witness the world’s biggest hangover and there’s fuck all Harold Wilson can do about it”. It could never last- the psychedelic movement, with it’s lofty intentions and idealism, was born to lose. In ‘Try a Little Sunshine’, the hangover can be heard to begin settling in- but, if the music heard here is any indicator, Britain’s psychedelic street party at least petered out with immense style and more classic records than you can shake a Camberwell carrot at.

Jack Hopkin

Try A Little Sunshine: The British Psychedelic Sounds Of 1969, Various Artists, 3CD Clamshell Boxset (Grapefruit Records 2018)

Well-written review, looks like an interesting box set worth checking out.