1966 Brit-Psych B-Sides

In this digital age, the phenomenon of the ‘b-side’ is an endangered one. All too often, the recordings which comprised the flip side of even the best selling 45rpm singles were relegated to obscurity. Oftentimes, this is fair- particularly within the confines of the 1960’s UK music scene. God knows how many half baked, rushed b-sides went out, groups being all too aware that the A-side was the moneymaker, what would gain them airplay on the pirate radio stations and perhaps win them a slot on Top of the Pops, with the B- side considered the stale space filler. I can’t even begin to count the number of songs named with variations on the obvious title ‘A Quick B’. It was, to understate enormously, often considered an afterthought. Take the Marquis of Kensington, for example, with their 1967 single, ‘The Changing of the Guard’. Here, the B-side, ‘Reverse Thrust’, was the A-side played backwards. Snap, crackle, pop, that’ll do, let’s get on with it.

That said, oftentimes the flipside was where a group would record their magnum opus. Following Decca’s failure to sign the Beatles, just about every label in the UK developed a manic paranoia of missing the next ‘big thing’. Between 1966 and 1969, there was a kneejerk signing spree that coincided with the rise of the most experimental period to date in British pop music. The A side was usually something radio friendly, but the B-side was where things tended to get downright weird.

In what may be one of the most succinct prophecies this side of Nostradamus, Brian Wilson of the Beach Boys predicted in 1966 that ‘psychedelic music will cover the face of the world and colour the whole popular music scene.’

He wasn’t wrong. As Carnabetian London’s white light and white heat began to cool off and the unsustainable neophiliac pacing of the modernest movement slowed to a halt, LSD- still legal in 1966- trickled down from the upper echelons of the art world and into the music industry. Inspired by the opaque lyrics of Bob Dylan, imperialist exotica and by the deep introspection afforded to them by acid, these musicians set about revolutionising the music industry from the inside out. As the sleevenotes to Sanctuary Records’ ‘Real Life Permanent Dreams’ compilation describes, this was ‘the beginning of a journey without maps; fey folkies, beatniks out to make it rich, pilled up mods, art school dropouts, R&B hoodlums and mop top beat merchants assembled like pied pipers at the gates of a strange new dawn’.

In this first installment of a retrospective glance at the B-sides of the mid to late 60’s, we’ll start by casting our third eye upon fifteen tracks from the year the psychedelic seed was planted, 1966. There’s no particular order and the list is enormously subjective. There’ll be entries selected by virtue of the fact they provide a gateway to discuss the wider context of the times, and entries that are there simply because they are downright good records. It should also be noted that the definition of ‘psychedelia’ differs from person to person. Not every entry is a bona fide psychedelic track by conventional wisdom, but rather they may pertain to the subculture in an important or interesting way. That’s only to be expected, especially here, given that 1966 was a transitional year and the genre didn’t emerge fully formed but rather evolved and mutated over the course of the year. Just a little disclaimer there- I don’t want to awaken to the sound of rattling bells and love beads because an angry flower mob has been worked up into a lather over the fact I didn’t include this record or that band and so on.

In other words, consider this a prologue of sorts. Setting the scene. We’ll get to the really good stuff later.

Without further ado- are we all sitting comfortably?

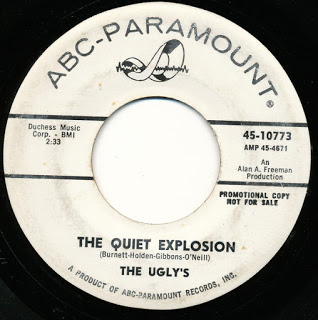

1: ‘A Quiet Explosion’- The Uglys (A Side: ‘A Good Idea’)

‘Be prepared for the quiet explosion’, we are warned over a trembling organ and reverberating bass in this unsettling ode to the atomic age. The Uglys, hailing from Birmingham, gained little mainstream success in spite of the airplay they attained on the pirate radio stations.

‘A Quiet Explosion’ is a lost psychedelic classic that forges a bridge between the CND protests of the start of the decade and the burgeoning counterculture. The shadow of nuclear annihalation hung heavy over the post-war generation coming of age in the 1960’s, with Jon Savage noting how, if the space of time that elapsed between the First and Second World Wars was anything to go by, the Third World War was well and truly ‘due’ by 1966. Films such as 1965’s ‘The War Games’ cemented these fears, with it’s graphic depiction of a post-apocalyptic Britain featuring harrowing scenes such as government santioned squads of soldiers burning heaps of corpses and policemen shooting looters.

In many ways, Swinging London was an orgy of pre-apocalyptic epicureanism similar to that found in the final days of Rome. The young, affluent middle class had a gun to it’s head and responded to an insane world in the sanest way it thought possible- through escapist fantasy, unbridled hedonism and heavy drug use. This eerily jaunty track is a fascinating facsimile of the fear of the quiet explosion, whilst documenting the genesis of a youth culture boom that was far from quiet. ‘Each helpless voice is a quiet explosion!’

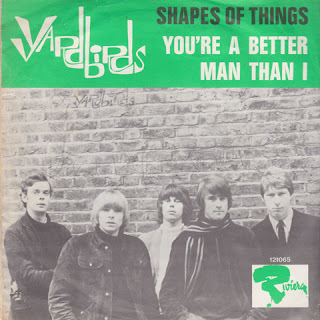

2: ‘Mister, You’re A Better Man Than I’– The Yardbirds (A- Side: ‘Shapes of Things’)

Can you judge a man by the way he wears his hair? Can you read his mind by the clothes that he wears? Can you see a bad man by the pattern on his tie? The Yardbirds ask all these questions and more as they address the growing generational gap on this flip side to the seminal ‘Shapes of Things’.

The Yardbirds were at the very forefront of pop music’s progression in the mid 60’s- indeed, 1965’s ‘Still I’m Sad’ is a contender for the very first mainstream psychedelic record. Famed moreso for their fast tempo ‘rave-ups’, the Yardbirds are in a more philosophical guise here as they come to grips with identity, perception and the moral panics of the time. Although this particular record preempts the existence of a coherent UK psychedelic ‘scene’, the scaffolding was in place. In defending the mores of the still embryonic counterculture, the Yardbirds quickly- but briefly- became the darlings of the cutting edge and avant garde circles in London, famously featuring in a discotheque scene in Michelangelo Antonioni’s era defining film, ‘Blow Up’.

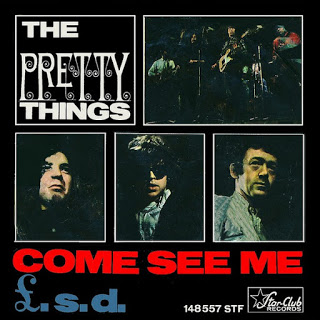

3: ‘L.S.D’- The Pretty Things (A-Side: ‘Come See Me’)

The official title of this song is £.S.D…. but are you really fooled? During the denouement of this chunky, guitar driven freakbeat gem, lead singer Phil May (who prided himself on having the ‘longest hair in London’) manically chants ‘Yes, I need L.S.D’ a total of seven, yes, seven times.

Not particularly subtle, but apt for a year where LIFE Magazine published a cover story on the drug subtitled ‘The Exploding Mind Drug That Got Out Of Control- Turmoil in a Capsule’. That’s the element of the psychedelic experience the Pretty Things choose to engage with here- no blissed out soundscapes but rather a rabid paced R&B workout with a lysergic gloss. Of course, this wouldn’t be the Pretty Thing’s sole flirtation with psychedelia; they would later release one of the key albums of the genre with ‘S.F Sorrow’ in late 1968.

4: ‘Rain’– The Beatles (A-Side: ‘Paperback Writer’)

Those who listened to the flip side of the Beatles’ ‘Paperback Writer’ in June 1966 would have been absolutely baffled. The most famous and successful band of the era had flirted with Indian exoticism (implementing a sitar on ‘Norwegian Wood’) and universal (rather than romantic) love on ‘The Word’ on 1965’s exceptional ‘Rubber Soul’ LP. Yet, this was the true beginning of the Beatles’- and, thus, the mainstream’s- flirtation with psychedelia.

A sonic tour de force replete with droning harmonies and backwards guitars, ‘Rain’ is the first fruit of John Lennon’s L.S.D influenced creativity which would gain further exposure a couple of months later on the groundbreaking ‘Revolver’ L.P. This is a psychedelic track free of the Victoriana whimsy which would later epitomize the genre, a track which preempts the Summer of Love and it’s flower power gimmickry by a year and as such is a more cynical piece more in line with ‘Revolver’s’ ‘She Said, She Said’. John Lennon would later refer to this as his ‘Tibetan Book of the Dead era’, not surprising given the book’s insistence that the reader turn off their mind, ‘relax and float downstream’. John Lennon welcomed this ‘ego death’ as a means of achieving a fresh start both personally and musically, a liberation from the frenetic pace of being at the eye of the storm of Beatlemania. Psychedelia was gaining mainstream acceptance, and was temporarily adopted as the genre of choice for the dying modernist movement as mod influenced groups such as the Attack, the Creation and the Small Faces began to follow in the Beatles’ footsteps. Anything the Beatles recorded ushered in a wave of copycat releases, deperately struggling to keep afloat and adhere to the blistering rate of musical progression.

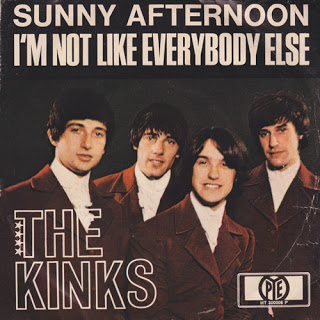

5: ‘I’m Not Like Everybody Else’– The Kinks (A-Side: ‘Sunny Afternoon’)

The Kinks are popularly remembered as eschewing the pervading psychedelic trend and maintaining their own unique sound and trajectory, but Ray Davies’ quintessentially English approach in his character studies ‘A Well Respected Man’ and ‘Dedicated Follower of Fashion’ were extremely influential in shaping the genre. Furthermore, ‘Face to Face’ is arguably the first concept album in British pop, a cynical and distanced remonstration against the airy fads of Carnaby Street as captured in the scathing ‘Dandy’. Ray Davies loathed the escapism and opulence of the King’s Road set and garnered inspiration from his working class upbringing. By the end of 1966, he was shouting above all the noise of the top 20 to remind us that ‘people are dying on Dead End Street’.

On ‘I’m Not Like Everybody Else’, Dave Davies- the archetypical Carnabetian dandy and not so secret inspiration for many of brother Ray Davies’ character assasinations- takes the helm and delivers a raw, defiant declaration of individuality. When he rasps ‘I don’t want to live my life like everybody else’, he gives a voice to the estranged proto-hippies who could imagine nothing worse than conforming to a society they didn’t agree with or belong to. Every bit as good, albeit not so well remembered, as the music hall influenced A-side, this track would go on to join the setlist of countless garage and freakbeat bands across the UK and the US- for instance, the American West Coast’s Chocolate Watchband would later issue a cover on their 1968 LP ‘The Inner Mystique’.

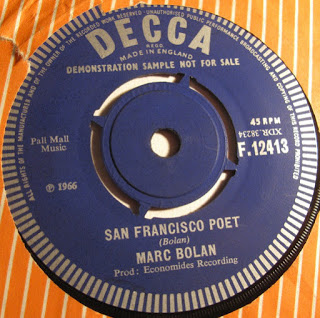

6: ‘San Francisco Poet’– Marc Bolan (A-Side: ‘The Third Degree’)

Marc Bolan very much had his finger on the pulse with regards to what was happening over on the West Coast. In ‘San Francisco Poet’, Bolan’s idiosyncratic, warbling vocal style is already present and foreshadows the more far-out material he’d later perform with Tyrannosaurus Rex.

‘The days of the beatniks are gone, the Bible’s all written wrong’, he bleats over chiming acoustic guitars. It really is a shame that Marc Bolan clearly possessed such lyrical talent, yet there remains a sizeable contingent who remember him primarily for such teenybopper 70’s hits as ‘Get It On’ and ‘I Love To Boogie’. San Francisco and London were, of course, two of the most prominent incubation spots for the new psychedelic sound and whilst both had a completely distinct and unique flavour to the other, they were still parallel movements that regarded each other with curiosity and intrigue. 1966 saw the Love Pageant Rally in San Francisco and the rise of a new wave of much imitated groups such as the Quicksilver Messenger Service, the Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company. Meanwhile, the growth of the ‘underground’ press in San Francisco with such bohemian minded newspapers as the Oracle influenced UK-centric publications such as OZ and the famed International Times. By the end of the year, Marc Bolan had joined the notoriously controversial freakbeat/protopunk group John’s Children.

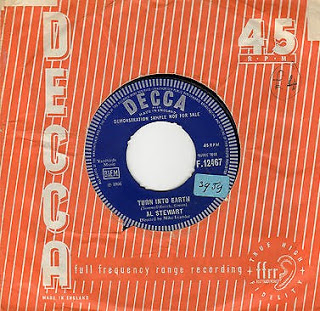

7: ‘Turn Into Earth’– Al Stewart (A-Side: ‘The Elf’)

Such an atmospheric record as this was surely a favourite of Jeff Dexter and John Peel’s DJ sets. Moody and ominous, with interludes of Gregorian chant and migrating flutes, Al Stewart pre-empts many of the production values of other, later psych tracks on the same label. Surely if Tintern Abbey recorded this (and by all accounts, this doesn’t sound too disimilar in terms of overall vibe to their cult classic ‘Beeside’) then copies of the single would be fetching hundreds of pounds in auction.

Al Stewart would go on to explore a similar, baroque, chamber music style in his excellent 1967 debut album, ‘Bedsitter Images’. Of course, Al Stewart was a predominantly folk oriented artist, performing at clubs like Les Cousins alongside the likes of Jackson C Frank, John Renbourn and Paul Simon. This early hybrid of folk and psychedelia foreshadows other lysergic efforts by British folk boom proteges such as Fairport Convention, who explored West Coast style psychedelia on their shimmering Judy Dyble fronted debut.

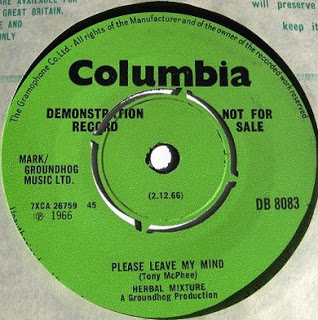

8: ‘Please Leave My Mind’– Herbal Mixture (A-Side: ‘Machines’)

For all the artistic merit of early psych, the music industry was still a business and records were still cut to be sold to the masses. As such, the cynical viewed psychedelia as yet another passing fad that would come and go within a few months. Fads existed to be capitalised on, and by the end of 1966 record producers everywhere hoped to strike the groovy goldmine. Beat era group names such as the Critters were no longer in vogue now that groups with names such as the New Vaudeville Band and Jefferson Airplane were coming to the forefront.

The Herbal Mixture was, in effect, highly rated blues band the Groundhogs operating under a psychedelic moniker, hoping the gentle drug reference would attract the new demographic. Not surprisingly, they reverted back to their previous name not long after this single was released and returned to more earthy blues based compositions. That said, ‘Please Leave My Mind’ features sole gently fuzzing, hazy guitar interludes and a pealing guitar pattern in the leading riff that borders on Byrds-esque. One of the first instances of a bandwagon-jumping psych record, it’s still very accomplished and impressive nonetheless, although not compiled as often as the A-side, ‘Machines’.

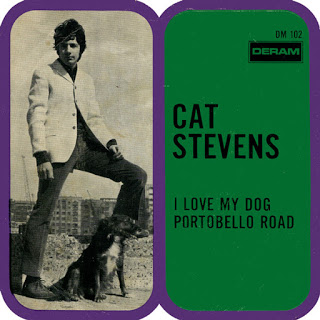

9: ‘Portobello Road’- Cat Stevens (A-Side: ‘I Love My Dog’)

Cat Stevens was only 18 years old when ‘I Love My Dog’ hit the charts. The B-side is an incredibly mature and candid portrait of a nascent counterculture reaching boiling point. Amidst the youthful, almost carnival-esque spectacle of the Portobello Road (the market there being a focal point for kleptomaniac scenesters), it seems the only danger is ‘growing old’ and missing the circus.

As Julian Palacios writes, ‘the underground pilaged their cultural history, smoking dope and rummaging for antiques on the Portobello Road… They embraced the shadow of their grandparent’s Victoriana, torn between an idealised future and rose-tinted visions of the past’. The quietly optimistic lyrics here are a time capsule of this transitional period, a world of cuckoo clocks, yellow ties and lampshades of old antique leather. The shift in fashion whereby Edwardian styles were revisited and repackaged in new boutiques, as at ‘Granny Takes A Trip’ and ‘I Was Lord Kitchener’s Valet’, is referenced- ‘nothing’s the same if you see it again’. The psychedelic movement at this time was redefining not just music and art, but also society’s social codes, ushering in a bohemian tinged wave of permissive open mindedness- especially here on Portobello Road, a place where ‘nothing looks weird, not even a beard’.

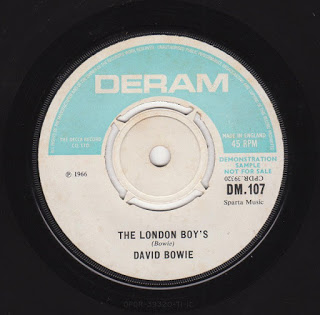

10: ‘The London Boy’s’- David Bowie (A-Side: ‘Rubber Band’)

Just as Cat Stevens captured the beginning of London’s new hippie youth culture, David Bowie captured the demise of their predecessors, the mods. Although Swinging London had all but fizzled out, the media continued to propagate the myth through films such as ‘Smashing Time’ and ‘Georgy Girl’. The allure of the mythic London, a youthquake utopia, often couldn’t live up to the commodified facade to the extent that some teen-orientated magazines featured interviews with pop stars warning teens not to make the pilgrimage, lest they regret the trip.

This is the case for the protagonist of this early Bowie epic, who is ‘only seventeen’ but thinks himself tremendously independent and hip in spite of having only been away from home for a month. It’s a cautionary tale- our narrator quickly learns that the mod scene is relentlessly consumer driven and ultimately vacuous in spite of all it’s superficial charm.

‘Now you wish you’d never left your home/You’ve got what you wanted but you’re on your own/With the London boys’, the young Bowie taunts at the climax of this track. There are definite music hall leanings, something that would become very prevalent in the following year’s recordings. The remaining mods either evolved to become psychedelic dandies (in the case of the more affluent members of the subculture), whilst the working class contingent formed the basis of what would later become the skinhead subculture of 1969.

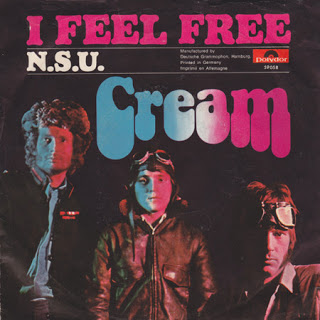

11: ‘N.S.U- Cream (A-Side: ‘I Feel Free’)

Cream are often credited as being the first ‘supergroup’, with each member of the power trio having found some level of success with previous bands. Drummer Ginger Baker was formerly a jazz drummer- and the freeform time signatures of jazz would soon be appropriated by the psychedelic movement.

Cream’s lyricist, Pete Brown, noticed this parallel between jazz and psych. ‘Jazz takes you on journeys and they would really take you somewhere. The psychedelic element is that we were taking people on a journey in a different way than before’. The group’s debut, ‘Wrapping Paper’, and even ‘I Feel Free’ are heavily jazz influenced, but ‘N.S.U’ points towards the heavier riff-based work Cream would later go on to pioneer and epitomise in albums such as ‘Disraeli Gears’ and ‘Wheels of Fire’.

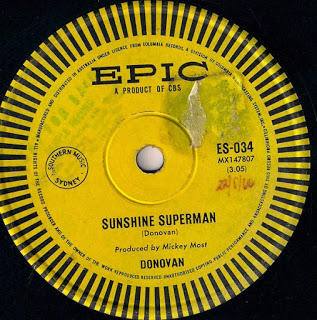

12: ‘The Trip’- Donovan (A-Side: ‘Sunshine Superman’)

A stream of consciousness psychedelic journey across Los Angeles, Donovan’s ‘The Trip’ sees the former beatnik and folk singer transition into one of the first true exponents of flower power. Along the way, he gets ‘caught in a coloured shower’, meets ‘the mad hatter’ Bob Dylan and laments that ‘the whole wide human race has taken far too much methedrine’.

Donovan had toyed with psychedelia in his earlier folk recordings, such as ‘Sunny Goodge Street’, with it’s surrealist lyrics depicting a ‘violent hash smoker’, a ‘crazy Kali goddess’ and a ‘magician sparkling in satin and velvet’. Yet, this is where he emerged from Bob Dylan’s shadow and became a unique voice in the psychedelic movement, melding medieval sounds and mythology with references to key countercultural happenings and figures. 1966 was a key transitional year for Donovan- an expose titled ‘A Boy Called Donovan’ aired, featuring a scene in which he was filmed smoking marijuana. A visit from Sgt Pilcher’s notorious drug enforcement squad naturally followed soon thereafter with almost comic inevitability. The troubador largely catered to the US market, with several of his later records being released solely in America, but ‘The Trip’ and it’s glittering A-side ‘Sunshine Superman’ took the UK by storm in the winter of 1966-67.

13: ‘Disturbance’: The Move (A-Side: ‘Night of Fear’)

The Move prided themselves on being provocative. Taking Gustav Metzger’s autodestructive art to new heights, they even rivalled the Who in terms of pop art antics. Often appearing onstage dressed in gangster regalia, they were known to attack television sets and effigies of politicians with axes during the climaxes of their aggressively charged live performances. These high profile media stunts initially overshadowed the band’s music.

The A-side takes it’s distinctive riff from Tchaikovsky’s ‘1812 Overture’, foreshadowing the fascination with classical music that would spawn Procol Harum’s Bach-esque ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ and Love Sculpture’s breakneck rendition of Aram Khachaturian’s ‘Sabre Dance’. ‘Disturbance’, however, is prime psychotic freakbeat, a hook laden (and definitely not particularly politically correct) tale of a man driven to madness. It even ends with a coda of hypnotic chanting, slamming prison doors and incoherent babbling that builds into a crescendo of blood curdling screaming. Psychedelic? Yes. Blissed out? God no.

14: ‘Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix Experience (A-Side: ‘Hey Joe’)

I know, I know. Jimi Hendrix was an American. But the Jimi Hendrix Experience? A British band with an American frontman. Besides, it was the UK scene where Hendrix’ s records had their greatest success and greatest influence, so I’ m including him here for that reason alone.

Keith Shadwick calls ‘Stone Free’ a ‘countercultural anthem’ with lyrics praising the restless lifestyle of it’ s author. ‘Hey Joe’ is a classic recording, but one on which Jimi’s playing is much more restrained and plaintive. ‘Stone Free’ , however, is the perfect vehicle for Jimi’ s manic riffing and Mitch Mitchell’ s powerful driving drumbeat. Jimi Hendrix made an enormous splash upon his arrival in London in 1966, quickly earning the affections- and even resentment- of fellow musicians such as Paul McCartney and Eric Clapton.

15: ‘Who Do You Love’- The Misunderstood (A-Side: ‘I Can Take You To The Sun’)

Another batch of American ex-pats who nonetheless deserve a place on the list given their Anglocentric traits. Hailing from Riverside, California, the Misunderstood were enormously influenced by the Yardbirds and quickly won favour with John Peel, who brought them home with him to England.

In ‘Who Do You Love’ , the sun guitarist Glenn Ross Campbell’ s (no, not that Glenn Campbell) scintillating steel guitar soundscapes transform this Bo Diddley number into a psychedelic paen to free love in the same vein as Jefferson Airplane’ s ‘Somebody to Love’ . Upon it’ s release in December 1966, it was very much in place with the spirit of the times. The UFO Club opened that same month, attracting an enormous audience to see Pink Floyd and Soft Machine play space-age music not dissimilar to both sides of this particular disc. It is the reimagining of old blues conventions that contributes to the Misunderstood earning their place on this list, given how much British groups such as the Rolling Stones owed to the blues. Above all else, this is just a bloody good record. Pure psychedelia, before the gold rush and trial by media commodification. Regular airplay on John Peel’ s Perfumed Garden radio show the following year would rightfully establish both ‘I Can Take You To The Sun’ and ‘Who Do You Love’ as early classics of the genre.

– Jack Hopkin

Array