The Rise and Fall of Willie & The Walkers

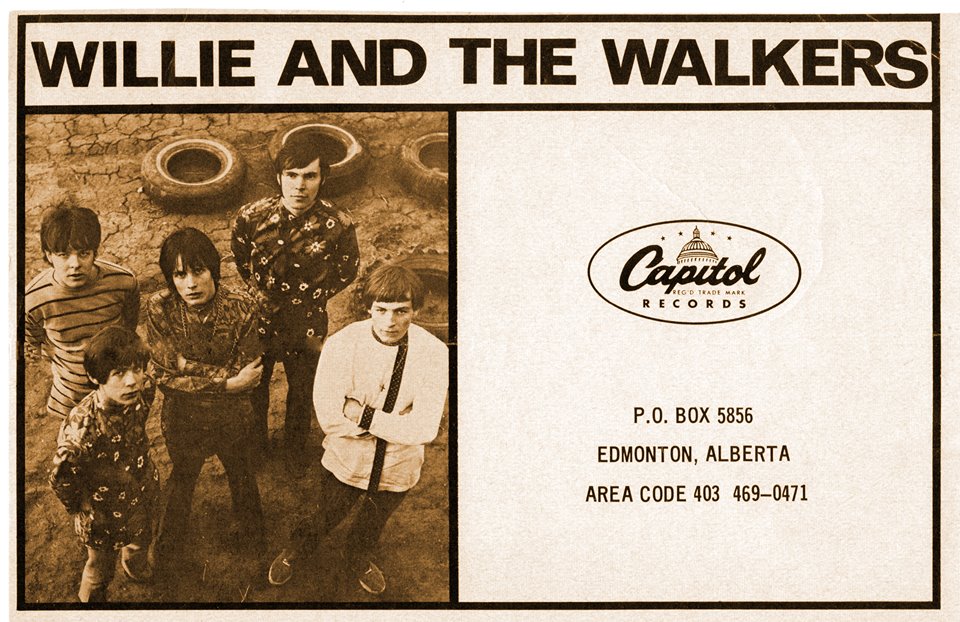

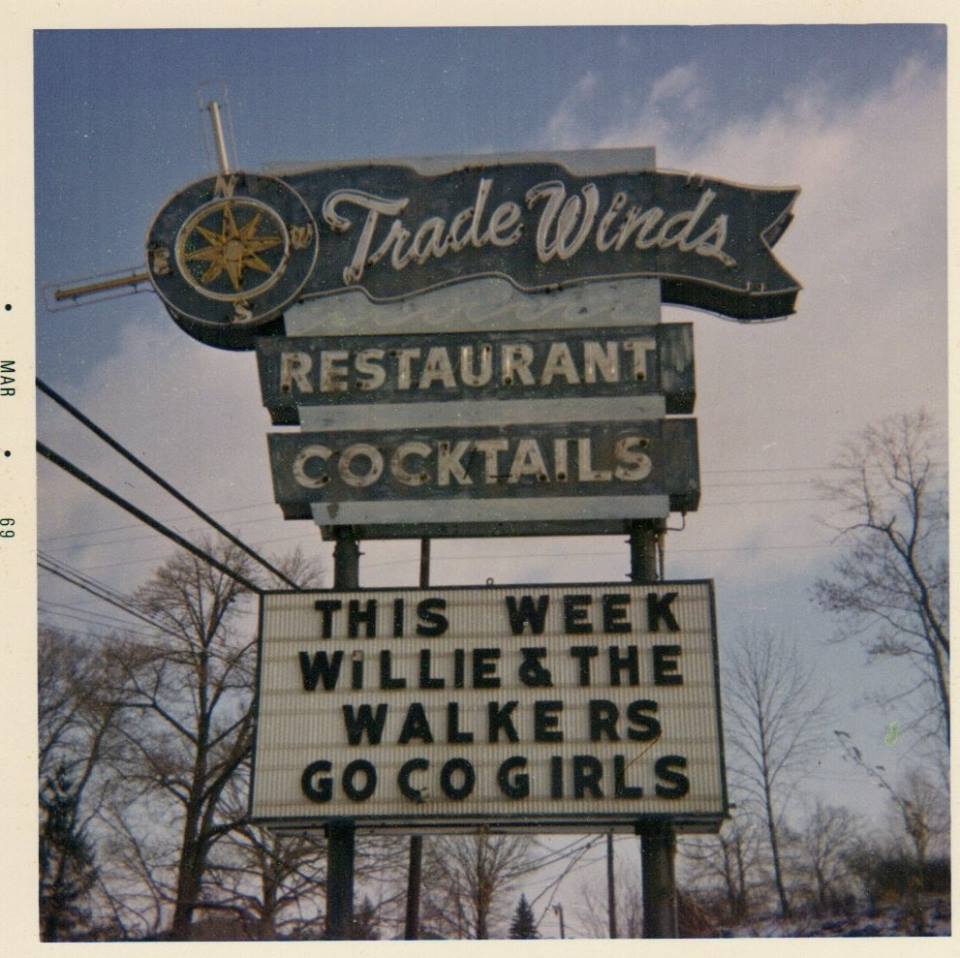

The seven years from 1965 to 1972 was a magic period in the history of Canadian popular music. Nowhere was that more true than in Edmonton. Alberta’s capital had a relatively small but remarkable musical scene – it could boast of two recording studios: CJCA and Downtown Recording Studio (later called Park Lane), three record labels: Pace, Damon and Molten, four booking agencies: Rayal Talent, Amroux Enterprises, Spane International, and Studio City Musical Ltd., three radio stations playing popular music: CJCA, CHED and CFRN, hip disc jockeys such as Bob Stagg, Chuck Chandler and Bob Gibbons, a popular music promoter like no other – Benny Benjamin, numerous hip nightclubs such as the Sugar Shack a-Go-Go, the Outer Limits, Zorba’s, the Forum, the Rainbow Ballroom, the Lakeview Pavilion, and finally a network of neighbourhood community halls which promoted local rock bands every weekend.

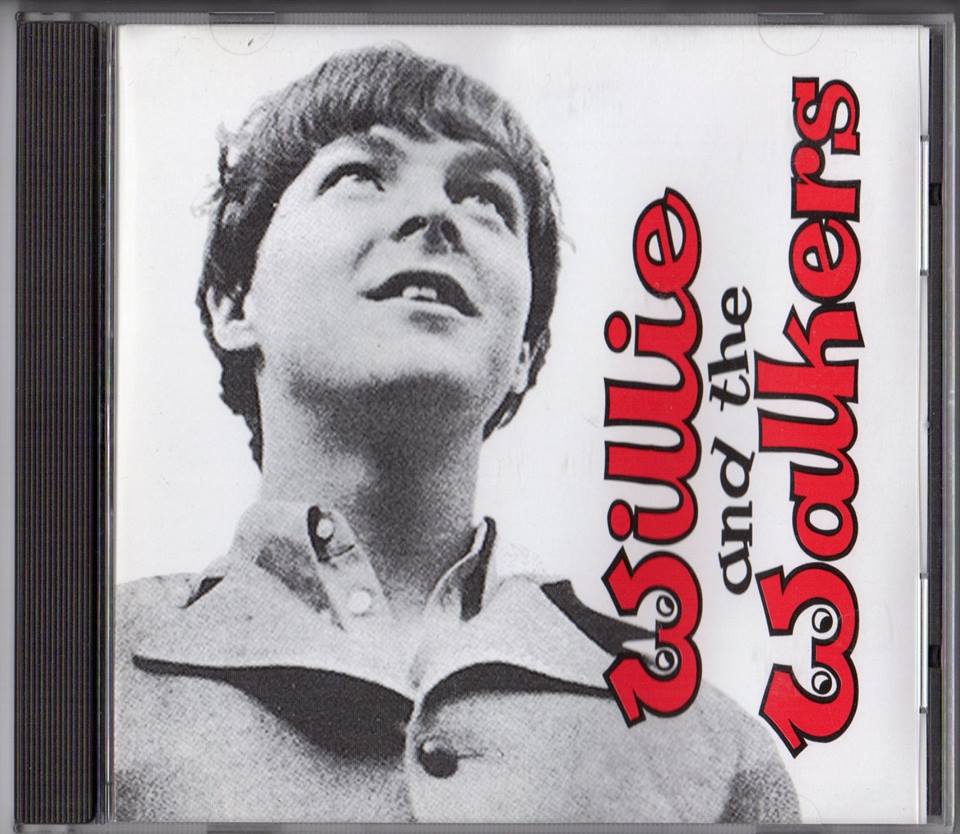

Edmonton was a nexus for original talent as well, with artists such as Mary Saxton and Barry Allen, and bands such as Wes Dakus & the Rebels, The Pharoahs (shortly to be renamed James & The Bondsmen), The Nomads, The Kingbeezz, the Lords (later to be rechristened Privilege), and L’il Davey & The Drastiks, Southbound Freeway, Graeme & The Waifer, The Young Ones, Cheyenne Winter, and Warp Factor. Most of these enjoyed regional fame, and several made it onto the national stage. Leading the pack for much of this period was the band Willie & the Walkers.

The original lineup included teenagers Will MacCalder, Bill Hardie, Rolie (Roland) Hardie, and Dennis Petruk. MacCalder, who would emerge as the band’s leader, was born in Victoria BC in 1947, but his family moved to Edmonton when he was an infant. His father was a contractor in the oilfields of Leduc. MacCalder was an early follower of the CFRN Hit Parade, and clearly recalls his liking for Bing Crosby, Jim Reeves, Prez Prado, Hank Williams, Patti Page, and later Fats Domino and Elvis Presley as he arrived at teenage-hood. He took piano lessons from a Mrs. Brooks in the Parkallen subdivision, but as it was classical music he was being taught, his attention wandered. He particularly enjoyed going through his grandparents and parents’ 78 rpm collections. His mother possessed what might have been his favourite record: Fats Waller’s “The Joint Is Jumpin’” with its lyrics “…get your hands off that broad, put away that pistol…”

There was a MacCalder household rule that strictly prohibited guitars, so Will, at the age of thirteen, took alto saxophone lessons at a local music store Harmony Kids. That led into his first band – a trio called The Barons – with drummer Ken Avison and guitarist Wes Shannon, playing songs like “Tequila” (The Champs) and “Wild Weekend” (The Rockin’ Rebels) at community halls. When they ran out of songs, Avison – a magician in training – continued the entertainment with his act. That was followed by The Casuals with Leonard Saidman, Marilyn Gardiner, Terry Merriman, Tony White and Ross Onyschuk.

In 1965 MacCalder graduated from Strathcona High and enrolled at the engineering school at the University of Alberta. After one term though, he found his enthusiasm waning, and he re-entered the world of music by joining The Tempests, again as a sax player. The band already featured the much acclaimed boy wonder drummer by the name of Rolie Hardie. The two hit it off immediately, and Hardie’s musical feel was used to bring MacCalder into the real world of music. Remembers MacCalder: “I thank him from the bottom of my heart. He taught me what it was to play in time! And he caught me on numerous occasions playing out of time! He just had the knack. He was a musician and I was just hacking time in comparison.”

The group wore powder blue Beatle jackets, and performed mostly instrumental hits of the day such as “Miserlou” (Dick Dale and the Deltones), “Telestar” (The Ventures) and “The Rise and Fall of Flingel Bunt” (The Shadows). The instrumentals were exciting but limiting, and thus MacCalder decided to make his vocal debut with Rosie & The Originals’ “Angel Baby.” He not only made it through without forgetting the lyrics (“it scared the shit out of me!…but I got nice applause…”), and was thus hooked on singing. As well he started playing the keyboards at this time – at the same time he got to know Barry Allen:

I met Barry Allen at a meeting of the Barry Allen Fan club, organized by president Sorelle Saidman. At one of these meetings the Tempests played. Barry would try to sing along with us – try to follow us. Barry was so cool – he could do Marty Robbins tunes, and here we were having trouble with “You Really Got Me.” That day the organ player didn’t show up…he didn’t even show up to pick up his organ…he had already left Edmonton, so I said “I’ll play it.” Everybody encouraged me, and we started really simple – “Louie, Louie.”

Another major component of the impending Walkers were the Hardie brothers – Bill and Rolie. They had been playing for some time before they became acquainted with MacCalder. Bill – born 1946 in Kelowna, BC – was the eldest son of Bill Sr. and Muriel Hardie. His formal training on guitar consisted of one year of lessons at the Olson School of Music, where for reasons he cannot quite remember, he concentrated on learning the Hawaiian steel guitar from Mrs. Clifford. As Hardie recalls with a chuckle “I’m sure visions of Don Ho went through my father’s mind! But it was not exactly what I was looking for – I knew there was something else out there…”

This false start was quickly remedied when he joined his first band, The Nobles, in the summer of 1963 which consisted of Hardie, Ron Slemko, Brian McKenzie, and on drums his younger brother Roland (Rolie) Hardie, born in 1949, also in Kelowna. They did primitive versions of instrumental hits such as “Walk Don’t Run” by the Ventures, and all members shared one amplifier.

They lasted a year, then Bill co-founded a slightly more sophisticated band called The Vacqueros with John Wesson, Mark Spacinsky, Pat Payne and the bespectacled guitarist Dennis Petruk. Although he started out playing guitar, Hardie soon switched to bass when it became obvious that no one else in the group wanted the job or was qualified to do it. They also dressed smartly – red velvet Spanish jackets with gold braid, black cummerbunds, and black trousers with a gold stripe down the side. They had synchronized dance steps and were not afraid to use them.

In the last few months of their existence, they recruited Rolie Hardie from the Tempests. As local musician Steve Boddington recalled in a blog:

It wasn’t until Jr. High school that I saw my first live band. “The Vaqueros” played Ottewell school. This was momentous because the drummer was Rolie Hardie who went to our school. They had matching blazers and had big time professional gear – Fender amps and guitars, and Rolie’s blue sparkle Slingerland drums. Denis Petruk played guitar and Bill Hardie was the bass player. Also, I believe the sax player was John Wesson….For a chubby kid with glasses…this was the road to perdition!

They then started looking over MacCalder. He remembers:

I was working as a stock clerk at Hughes Owens drafting supplies…and one day after work Bill Hardie and Dennis Petruk walked up the driveway…I knew them from the rival band – if you liked the Tempests, then you couldn’t like the Vaqueros and vice versa – We had met, seen each other around, and through Rolie they decided to ask me.

He gladly accepted, and Willie and the Walkers formed in August 1965, combining the core members of The Vaqueros with those of The Tempests. Their new name was an homage to their heroes at the time – Jr. Walker & the All Stars. MacCalder recalls the moment of the naming:

Dennis [Petruk] and I were driving on 76th Avenue, heading east through the Mill Creek Ravine. Jr. Walker and the All Stars were on the radio. Dennis said “We should call ourselves the Walkers”…I said “Yeh we could, but how about Willie & the Walkers?” And he said “that sounds pretty good.” They wanted me to be the focal point. I was ecstatic that I had this support from the band, and they were encouraging me to go ahead and sing and play the organ.”

The Edmonton Journal announced their formation in an article entitled “Organ Dominates New Sound Group”:

With a unique a-go-go beat and a new sound dominated by the organ, Willie and the Walkers made their debut as an Edmonton group only four months ago. Willie and the Walkers swing on stage in flashy short red jackets and black and gold pants. Newer outfits are planned. Spokesman, organist and lead singer is Bill MacCalder, Bill Hardie, bass guitarist; Dennis Tetruk [sic.], lead guitarist; and Rolie Hardie, drummer are the Walkers. The group is working on their own material and eventually would like to record. So far they play survey hits and newer songs. The Walkers have a different taste in music – soul music. They go for the Zombie [sic.], Beatle [sic.], and Paul Revere and the Raider [sic].

With their musical talents and complementary personalities, the Walkers gelled immediately, and quickly entered the ranks of Edmonton’s musical elite. For the first six months they were managed by local disk jockey Guy Good (the all-nighter “CHED Good Guy” – in real life known as Saffron Shandro) and their bookings – mostly high schools, churches, community halls and a club called The Pussy Cat A-Go-Go – were handled exclusively by Petruk’s aunt Sophie – known to all as “Toots.” Management duties were soon taken over by Wes Dakus. The founder of The Rebels was just bowing out of live performance, and saw his future (and money) in artist management, talent agencies, booking, and recording studio production.

In early 1966 the Walkers realized they needed to sign with a profession booking agency to get regular and better paying gigs. The only real choice was the Rayal Talent Agency. Rayal was founded by Ray Short and Al Johnson in August 1965. Working out of the Rayal Building at 10534 – 109th street, they promoted themselves as Edmonton’s first talent agency for popular music acts. By 1967 they had signed fifty bands, and their star acts included Mary Saxton, L’il Davey & the Drastiks, and The Lords (featuring Mel Degen).

From the beginning The Walkers realized they had to use the best and state-of-the-art instruments – something none of them could afford. However MacCaulder arrived at an understanding with a local musical store. Petruk recalled in 1992:

Harmony Kids was a music store in Edmonton owned by the Barabash family. Ronnie Barabash kind of liked us guys and he said “I’m going to take a flyer on you guys. You guys pay us $400 a month”, which was a lot of money, because bands were playing for $200 a night, “and you can have any equipment you want.” And we said “Wow!” Willie had the first Echosonic portable organ west of Toronto. .

Willie and the Walkers had youthful energy to burn, and their adrenalin-pumping performances got them onto the Saturday morning “CHED Bandstand.” The program was broadcast live from two other hip clubs the Sugar Shack A-Go-Go and The Forum. It was a finely tuned (and ever-changing) balance between bouncy pop numbers like Donavon’s “Sunshine Superman” and the Monkees “Last Train To Clarksville” to increasingly sophisticated tunes like Peggy Lee’s “Fever”, the Yardbirds’ “Shapes of Things”, the Left Banke’s “Walk Away Renee” and the Beatles “Day Tripper” to flat out versions of garage band nuggets like “Louie Louie”, “You Really Got Me”, “Kicks”, “Wooly Bully” and “Lies”. They literally moved into the Petruk’s basement full-time – they rehearsed every day for at least 5-6 hours, followed by a record – listening session looking for new material. Claims MacCalder:” we would change our set completely every three months.”

McCalder was still trying to master his instrument during this period. He learned organ solos from the records note for note (“I thought Alan Price’s solos were really good…as for Rod Argent [The Zombies] – I didn’t know where he was going…). There was very little improvisation onstage, and only one or two organ solos at all. Of course it may have sounded thin and cheesy for he was playing it all with his right hand. His left was occupied with working the equally cheesy light show.

MacCalder recalls gigs at the Sugar Shack A-Go-Go, managed by Dennis Hogarth and located at Stony Plain Road & 150th Street: “We got a great audience reaction. The kids just loved us – we had choreography, flashy suits, we played all the hits, AND we were the same age as them! To hear a live band in 1965 was not to be taken for granted.”

At least six (and one band member remembers up to ten) of their live broadcasts on the CHED Bandstand were recorded on the station’s log tapes. The band would make a point of going to the station to listen to them as a reference point for judging and shaping their live act. MacCalder recalls: “I remember listening to myself try to sing “And I Love Her”…they were so rough, and I was so out of key! And I was thinking – that was broadcast? Oh stinkage!”

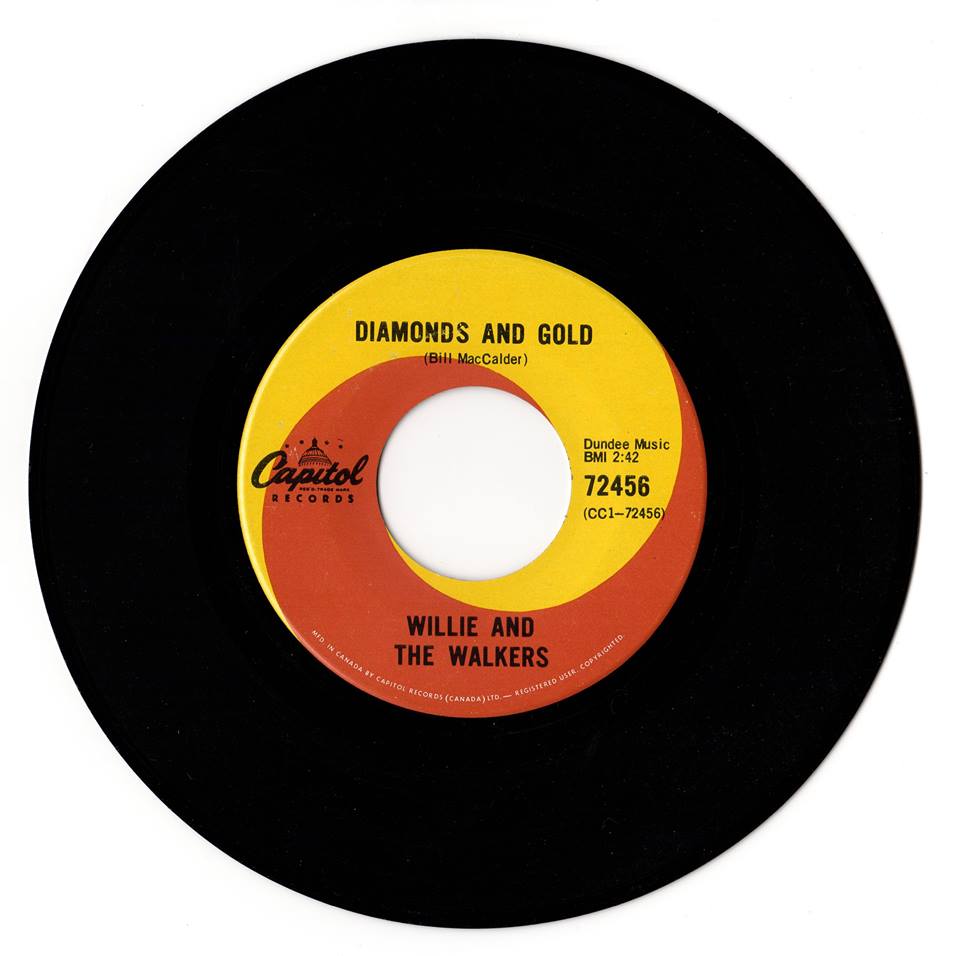

Unfortunately no one thought to make dubs and thus the band’s live performances have not been saved for posterity. Word of these programs however started to attract the attention of record companies, but the band had no demo tape to give them. Accordingly in the late summer the band followed the lead of their mentors – Wes Dakus and Barry Allen – and drove down to New Mexico to record several songs for a demo tape. From the beginning the Walkers were intent on only recording their own songs and, except for a few notable exceptions, all of their released material was self-penned. MacCalder’s first hurried composition, based loosely on the “Walk Don’t Run” progression, was “Diamonds and Gold”. His second “Baby Do You Need Me” was patterned after The Animals “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood.” Petruk offered up “Can You See” and “Just Don’t Pretend.”

Capitol Records, 72456, author’s collection

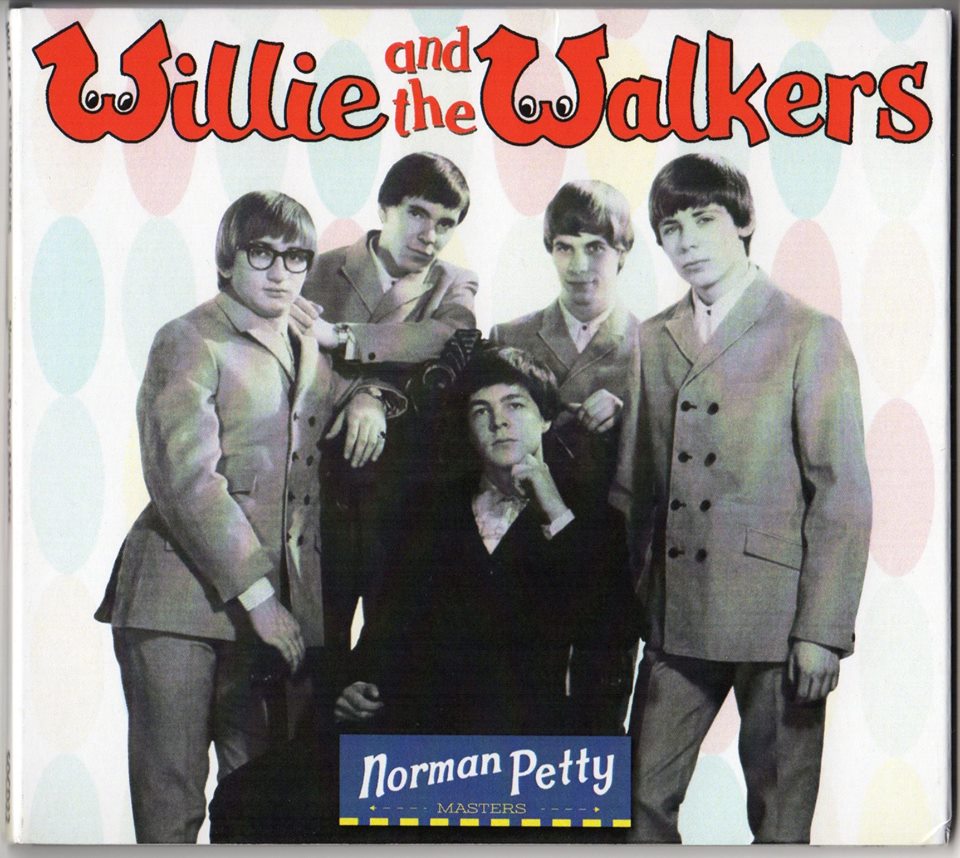

The site for their first recording session was the Norman Petty Studio in Clovis. Founded in 1954 by Petty (Buddy Holly’s producer and co-writer) it was a small and not particularly impressive edifice. Its dimensions were 10 ft. x 22 ft. and was described by Holly’s biographer as resembling “a 1930s gas station.” Still it had a most impressive track record. Roy Orbison had recorded “Ooby Dooby” and “Trying To Get To You” in 1956, Buddy Knox had put his 1957 million-seller “Party Doll” on tape there, Buddy Holly had recorded his two hits of 1957 there “That’ll Be The Day” and “I’m Lookin’ For Someone To Love”, and finally Jimmy Gilmour & The Fireballs recorded their “Sugar Shack” there in 1963. Add to this Petty’s publishing company and independent label Nor-Va-Jak, and it is not surprising that the establishment had a reputation second only to Sam Phillip’s Sun Studios.

The actual sessions, at which the four songs were recorded, took place over two sweltering days in July 1966. Even though they were extremely well rehearsed, MacCalder recalls that “we had to do seven or eight takes of each song before Norman heard something he liked.” He adds that Petty offered helpful hints: “He encouraged me to sing softer, more airy – put more breath into my voice. I’d never had any coaching, so I guess I was barking into the microphone!

It was an eye-opening experience for the tender young musicians. The studio was equipped with an Ampex 4 track recorder, then state of the art, as well as Telefunken and Neimann microphones. And, in particular the listening back to a properly recorded and separated piece of music on studio monitors with each track coming out of one of the four speakers was initially breathtaking. MacCalder:

I remember the first time I ever heard a playback of our music in a professional studio. It just did not relate to my ear. I thought “Who’s this? What is Norman playing us? I thought Norman was playing some sort of trick on us to show us what we should be sounding like. It was so clean and powerful! For a while I was really disoriented until I recognised that it was what we had just played! What a feeling!

Barry Allen helped with the harmony vocals. Again MacCalder:”…he learned the John Lennon/Phil Everly fifth below. Most people would take the thirds above – the most used harmony. Barry was such a monster harmony singer!!” Petty’s wife – Vi – came in after the band had returned home, and “sweetened up” some of the tracks with her organ. It did not help- instead it made it sound like MacCalder was playing a Teeny Genie organ which did not add to their credibility. Says MacCalder with commendable understatement:” We all thought it sucked.”

The timing was good – as they were starting to get mentioned on the national stage. Canada’s music industry magazine RPM dedicated most of its July 18th, 1966 Special Issue to music in Edmonton. The lead article “Edmonton: Canada’s Music City in the West” discussed the music infrastructure that was slowly coming together. There were numerous advertisements by local broadcasters, clubs, and the two talent agencies. It confirmed that there were “fifty regular working bands, several orchestras…small combos, country artists and jazz musicians are all deriving a fairly substantial living from their profession…” It ended with a warning:

Edmontonians have a liking for Edmontonians, which is a good start. Groups and artists are content to make a name for themselves in their hometown, and then gently spreading nationally. Watch for The Nomads, The King Beezz, James and the Bondsmen, Willie and the Walkers, Graeme and the Waifers, The Cat Family, the New Executives, The Exiled, the Kick a Poos, Today’s Specials, Sons of Adam, The Tyme Five, Fab 5, Famous Last Words, The Colours, and many more exciting Edmonton talent. Edmonton is truly THE MUSIC CENTRE OF THE WEST.

As early as September of 1966, Dakus had hyped the Walkers to another of his influential friends in the music industry – Paul White, then head of A&R at Capitol Records Canada. Based in Toronto, White had earned an immense reputation for spotting talent – three years earlier he had decided to release the single “Love Me Do” in Canada by a hot new Liverpool band, even though Capitol Records in the U.S.A. had passed on it. A couple of years later he would sign Anne Murray who would go on to become Capitol’s most popular and highest selling Canadian artist. White obviously liked the Walker demos, but did not want to make too quick a decision.

By November 1966, the Journal could report that:

Bill MacCalder of Willie and the Walkers has been given Jan. 1 as the tentative release date of the record the group recorded in Clovis, New Mexico. There is some talk about it being on the Capitol label.

Capitol finally took the plunge and signed them in early December. It was an auspicious period for the label. Under president Edward Leetham, and Paul White, they started to recruit and promote Canadian talent all helped by the profits pouring in from Beatle sales. By mid-decade, they had signed Les Atomes and Les Cailloux (Quebec), The Esquires and The Staccatos (Ottawa), Gary Buck (Sault St. Marie), Sugar Shoppe, Jack London & the Sparrow, Malka & Joso (Toronto), and from Edmonton Wes Dakus, Stu Mitchell, Barry Allen, James & the Bondsmen, and now Willie & the Walkers. They also started distributing several independent labels such as Hawk Records (Ronnie Hawkins, Robbie Lane), Roman Records (David Clayton Thomas & the Shays, The Paupers), and Yorktown (The Ugly Ducklings).

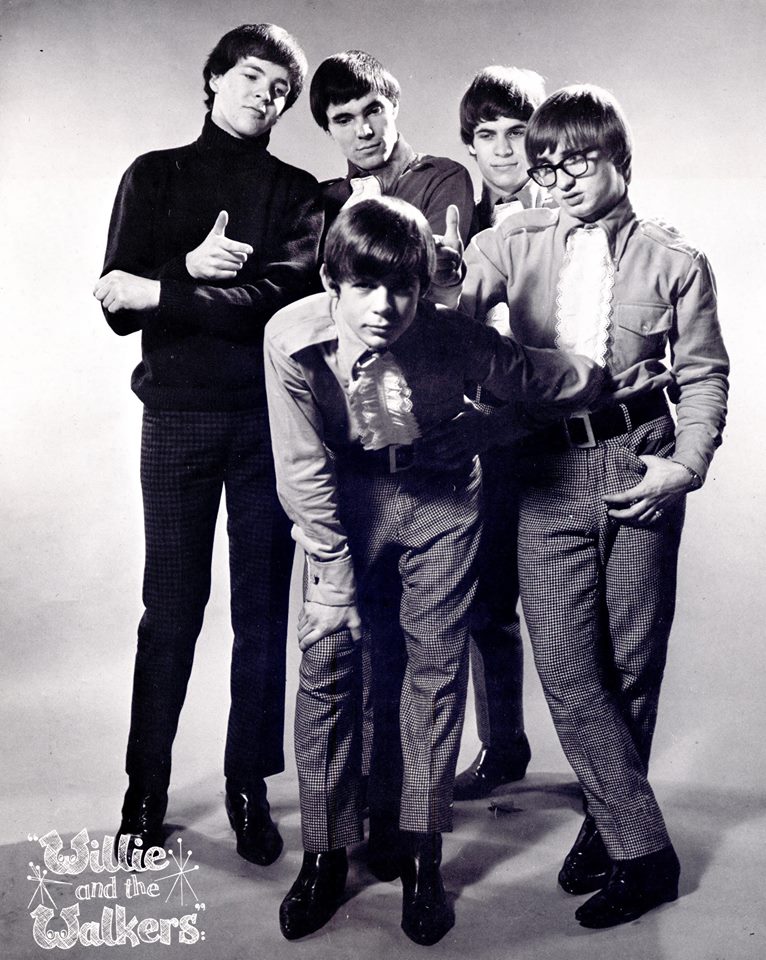

One could accuse Willie & the Walkers of being what we now know as a “boy band.” They had the boyish good looks that caused girls to scream – and it did not hurt that MacCalder, with his puppy dog eyes, bore more than a passing resemblance to Paul McCartney, and as a vocalist reminded listeners of Colin Blunstone of the British band The Zombies. They also had a somewhat fanatical Willie and the Walkers fan club which was started in November 1966 under president Barb Eastland. However the key difference was that they could write songs and could play their instruments – they were musicians first and foremost. And hoping to add to their fan base, The Walkers engaged in their first out-of-province “tour” the week after Christmas – hitting Lloydminster, Saskatoon and Regina in the music-conscious province of Saskatchewan.

At the beginning of January 1967, the Walkers decided to add a fifth member to augment their sound. Their choice was guitarist Bob Dann. Dann (b. 1947) was self-taught, and showed an early interest in jazz guitar. His formative influences included Wes Montgomery and Howard Roberts. However he too got caught up in the popular music boom of the early 1960s, and joined his first band in high school – The Pharoahs. Led by Dennis Ferbey, it included drummer Tommy Doran, and singers Judy Singh and Brenda Morrison. They became regulars on the CHED Bandstand radio program hosted by disc jockey Keith James. By 1965 their sound had evolved: they became enamoured of James Brown and other American rhythm & blues, and thus added a horn section consisting of Larry Hunter (saxophone), Jack Gordon (trumpet), and John Rutherford (trombone). As they were getting ready to record, they had the sinking feeling that they would not be signed by a major record company, and could even get into legal trouble if they kept the name Pharoahs. After all there was one extremely popular band – Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs – out there.

Keith James suggested they change to James & The Bondsmen, obviously to cash in on the 007 phenomena. The Bondsmen recorded a number of tunes in the Pepper-Tanner Studio in Memphis. As Dann Recalls: “Again it was Mr. Keith James. He knew these people, and actually the studio we used was a jingle studio…my interpretation [is] “We’ll buy the package off you if my boys can come down and record in your studio.”

They were signed to Capitol Records, and released three singles: “El Toredo” b/w “Get Smart”, “Look What You’re Doing to Me” b/w “Mister Soul”, and “Soup Time” b/w “Have You Ever Had the Blues.” For the last half of 1966, Dann jumped over to the Time Machine consisting of Bruce Nessel, Al Treen, Ken Brenzan and Steve Palmer. Palmer recalls : “The Time Machine played a lot of country dances doing the wrong kind of tunes. The people wanted the Monkees or Don Messer and we thought we were the Rolling Stones or the Fugs. It got tense sometimes….”

Dann bailed on this, and started teaching guitar at this point. He is still scratching his head:

How I thought I could teach guitar when I didn’t know how to read music I don’t know! I did that for a while, and then Will asked me and I said, “Sure, I’ll help out. If it doesn’t work I’ll go back to this, but I’m not here to take over the group, I wanna help you out.” That was my understanding—let me help you musically where I can and let’s get on with it. The ‘Journal’ thought Dann’s addition was newsworthy: Willie and the Walkers just back from a successful tour of Saskatchewan, have now added a new member to the band. Bob Dann, lead guitarist of the now defunct James and the Bondsmen, now plays six string lead guitar for the Walkers, while Dennis Petruk plays twelve string electric lead.

The Walkers moved into high gear during 1967. They were obviously listening to the right advisors and acquired their own practice studio near the corner of 101st Avenue & 72 Street (needless to say, it was also a serious party space), and formed their own company to handle their bookings. As reported in the Journal on January 27: “Willie & the Walkers, one of the best bands to come out of Edmonton, have formed a corporation to handle their bookings and engagements.”

They played a number of important concerts that winter and spring. In February they performed at the Muk-Luk Mardi Gras:

Willie & the Walkers will also be featured at the Muk-Luk Dance. New Walker Bob Dann had done wonders for the group’s sound. Their show is alive, slick and professional. The main characteristic of The Walkers is that they know exactly what they’re doing and love doing it. It shows when they perform.

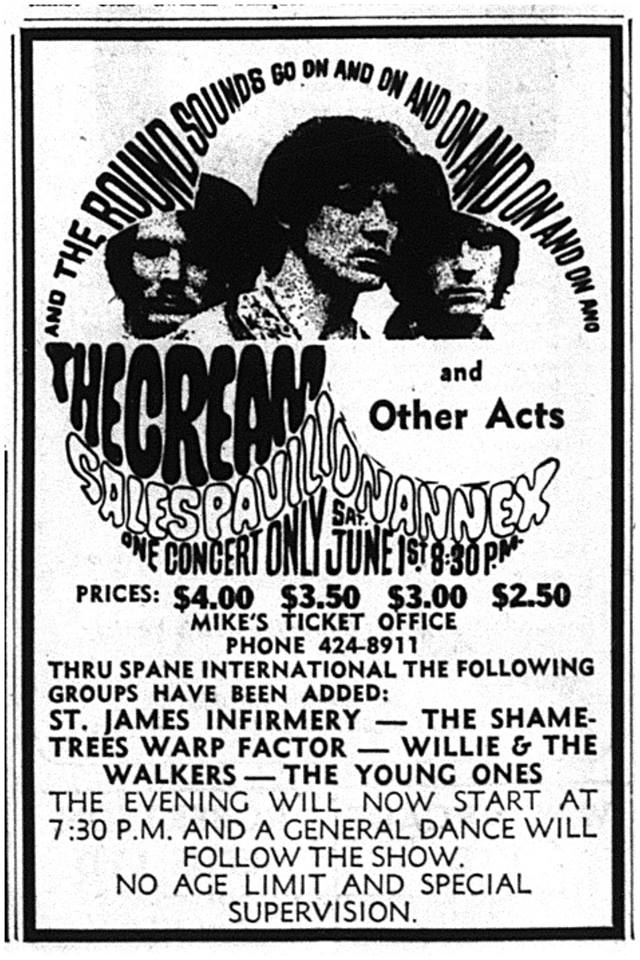

On March 18th, they opened for a four-band show at the Sales Pavilion headlined by Paul Revere and the Raiders and put on by the American firm Northwest Releasing. Barry Westgate of the Journal – normally pretty hip to popular culture – reviewed it like an old man. He bemoaned the:

… monstrous bashing on a set of drums at the back of the stage, to override, shape and insist the wild cacophony of noise that is this electronic age of teen-age entertainment. But don’t knock it too quickly. There were close to 5,000 teeny-boppers there and they simply loved it. No wild, wild screams. No concerted, panicky rush for the stage, but they loved it, all the way from Paul Revere and the Raiders of the upper echelons of teen entertainment to Willie and the Walkers of the local scene. In between were Roy Head and The Viceroys….The music didn’t matter, what there was of it. Just the beat, the flopping heads, the abortive gyrations….

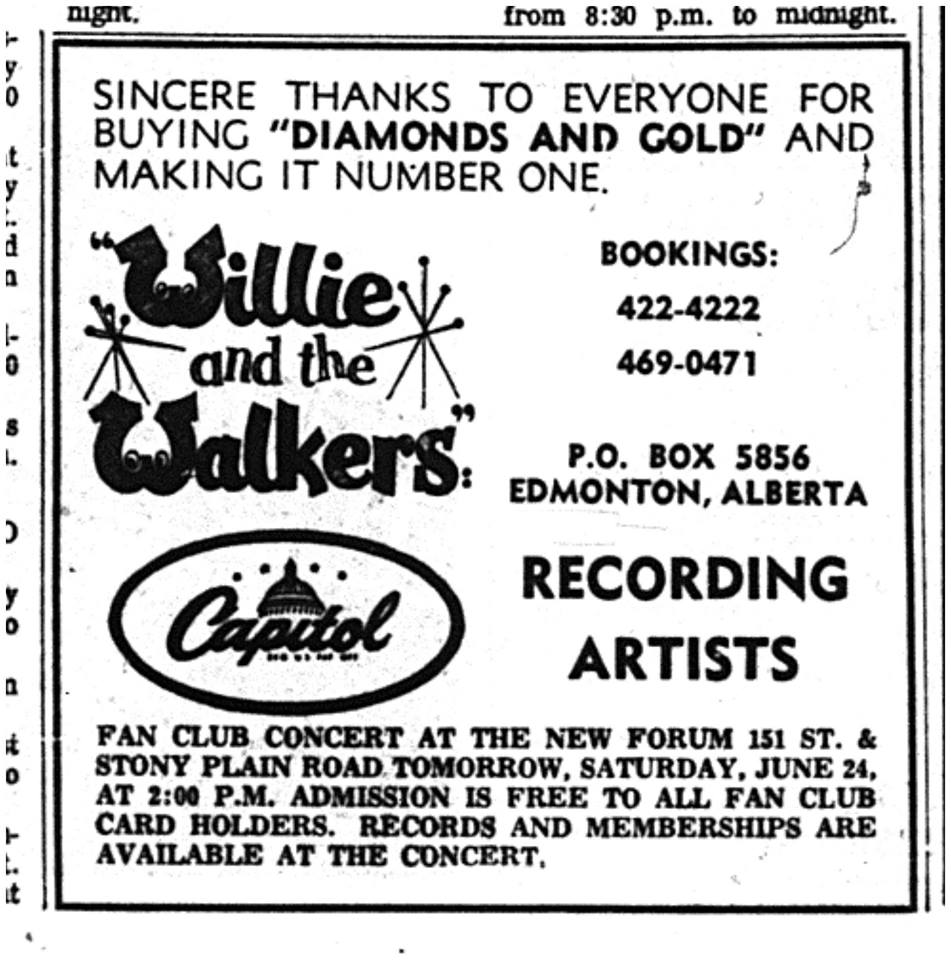

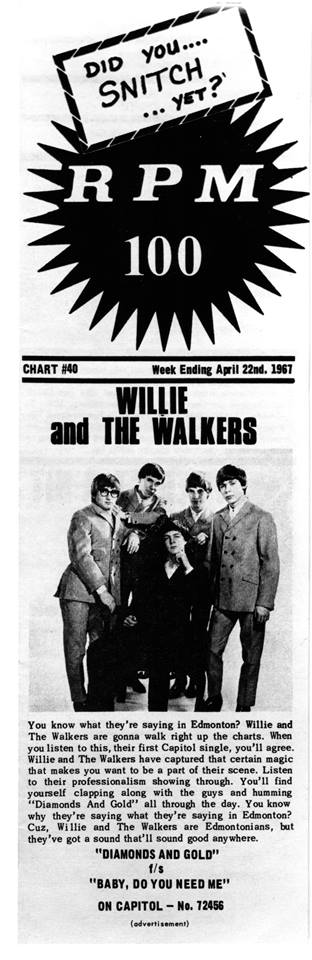

“Diamonds and Gold” was finally released at the beginning of May 1967. It entered the RPM Canadian chart at #14. It spent ten weeks on the chart, and managed to make it to #3 during the weeks of June 17th and 24th. That same May founding member Dennis Petruk left the band. Something was just not working. Of course it did not help that their first single had the two MacCalder-penned tunes they had recorded – not Petruk’s two songs. MacCalder:

It wasn’t premeditated. No one had a hate on for Dennis. He was such an important part of the character of the Walkers. The thought of going on without him at first was anathema…then I remembered a guy from Lethbridge who had an outstanding voice – Bryan Nelson. The Viscounts used to play at The Forum – his singing was so damn good – sort of like B.J. Thomas and Gerry Marsden.”

So under the headline “Walker Goes Walkin’” the Journal reported on April 21:

Dennis Petruk quit Willie and the Walkers last week. Brian Nelson (formerly of the Lethbridge-based Viscounts) was recruited into the Walkers ranks. He played his first dance with them on Friday night after three days of frantic practice sessions. He fits in very well. The Walkers will be leaving in a week for Clovis to record some new, original and better material.

Eli Bryan Nelson was born in Lethbridge, AB in 1947, a proud great-grandson of Ludger and Madeleine Gareau, close friends and co-conspirator of Louis Riel (and as he would put it – “a true native son of Canadian Federation and a man who gave his life willingly knowing one day his name would be cleared and his efforts would be recognized”). His family moved around – he was raised in Walla Walla & Spokane, Washington, then Calgary, and back to Lethbridge as a teenager.

My first band was a mostly instrumental group named The Chancellors. An excellent Ventures/Surf music/pop band led by the illustrious Dale Ketchison who left Lethbridge at 20 to study classical guitar in Italy with Segovia. I was brought in to sing Roy Orbison tunes and a couple of Beatles songs.

His next band was a touch more sophisticated:

The Viscounts did a lot of “show rock” stuff, emulating Paul Revere and the Raiders, Sam the Sham and the Pharoahs, Tommy Roe, The Kingsmen (“Louie, Louie”), and we were a great party/people band, although musically perhaps not top shelf.

Even so they were mirroring much of what The Walkers were playing at that time. Nelson became aware of The Walkers in 1966:

I first saw the Walkers at an underground rock club in Edmonton. They were great…I saw them again when they came and played a couple of weekend dates at Henderson Lake Pavilion, Lethbridge’s best teen dance place at the time. Saw them once more at the Edmonton club, then they came back the next week to watch the Viscounts play, and by the end of the week, Willie was talking to me about joining the group. By that point, Denny had given them notice that he would be leaving so they were looking for someone.

They wanted me as a singer and rhythm guitarist…The bizarre thing was that I was just a singer, not a guitarist, altho’ I think I may have played two or three tunes on rhythm guitar, but I could barely play… They were very cordial and complimentary. I was wowed by their sound, and especially their equipment and obvious business acumen. They were looking for someone to back up Willie; another lead voice that would also do quality harmony, which was a strength of mine. I knew that they had a few original songs, but there was no mention of songwriting as a focus. I doubt many bands went that route in that time, or hoped to make a living at it, although we could all see that the British Invasion bands were doing it with originals. Alberta at the time was rather insular, so the focus was really on doing a good job of playing the hits people were hearing on the radio.

As delighted as he was with joining the band, there was a downside too:

I worked very hard once I was in to not disappoint anyone. It was a difficult life as I had no place to stay, so for the first few months, I slept on a cot in the rehearsal space, which was located in a small strip mall. I was given a small stipend to buy food with, but it was a hand-to-mouth existence. I wasn’t very happy with it, but after a while, Roland and Bill’s family offered me a room in their home in the basement.

Dann welcomed Nelson, and thought he was:

Very positive, very upbeat. The only drawback to Brian was that he wasn’t very well. That was kind of heavy weight to wear around with us, because we’d have to be close to the hospital all the time. I don’t know if it wore on anybody else, but it wore on me a bit. But a very nice guy. He had the right idea; he was going in the right direction. He might have been a little faster than we were. Like, “Hey, come on guys, let’s catch up, let’s get going doing this…” and I think between him and Will there was a little bit of head-butting.

With Dann and Nelson, the band did a lot of practicing, in their studio and on tape. Dann recalls:

It’s all on Sony reel-to-reel, and I don’t know how many hours and hours of that stuff there is. We’d go in there and practice in sets and record it and then play it back. We’d spend hours and hours and hours. I don’t know where a couple of years went out of my life. I would go home three times a week to change clothes. I remember one morning getting up, and my mother said, “You’ve got a dentist appointment today,” and I said, “Oh yeah, that’s right!” I had just gotten home about two hours before that. We were rehearsing all night at the studio. She said, “Well, you’d better get going; it’s nine o’clock!” and I got up, jumped in my car, and I drove to the studio. Never did go to the dentist appointment. I went to the studio, sat there, nobody was there, I said, “What the hell’s going on? Wait, there’s no rehearsal! I was supposed to be at the dentist!” I was just so used to going there and doing that. We were so deep into it. Let me add, drug-free. We might have had a couple of bottles of beer once in a while, but we did all that without drugs. We were just really into it, actually to the point where it would blind us.

In Nelson, Dann found someone with an equally bent sense of humour. As proof MacCalder remembers one recording session that went sideways fast: “There’s a tape somewhere of us singing “Yellow Submarine.” But Bob Dann is singing as Mr. Spock and Bryan as Jose Jimenez – and this is without marijuana!”

Shortly after his joining, the band made their next trip to Clovis:

My first visit to Clovis was done with Barry Allen coming along as a guide and mentor. Barry had been there many times and was well liked and received by Norman and his wife. There had been a massive snowstorm in April? May? that had made the usual highways treacherous, so we drove to Clovis taking the long way around through Saskatchewan, nearly all the way to Manitoba and then down thru places like Wyoming, etc…Barry introduced us to Norman and the scene down there. We had a small number of tunes to record, maybe five or six. One of them was a song Willie wrote called, “My Friend”, which became a small cross-Canada hit. It was a ‘bubblegum’ song all the way, catchy and very danceable. We barely had time to drink Clovis in, then returned to Canada. Capitol Records (thru, I believe, Wes Dakus’ connections) quickly pressed and released “My Friend”. It was all new to me to be involved in a band that had some clout at that junior level.

Nelson recalls the trips were gruelling no-stop affairs:

Willie was a serious driver, which means you’d better go to the bathroom when you have the chance. Our lead guitarist Bob Dann, a very funny guy, had been asking Willie to stop somewhere, anywhere (we were out on a major stretch of highway with little traffic, so it wouldn’t have been hard to pull over and let Bob out for a minute, but the car kept going. Finally, Bob made Willie laugh and he pulled over. When the car stopped, Bob cried out, “Oh! Thank you, God!” and we all laughed, but let’s say Willie could be a very hard sell.

Another band member remembers his no-nonsense approach on the road:

We were coming from Moose Jaw through Medicine Hat. Will was driving as usual, and he hit a piece of highway that had gravel, and we had a station wagon and a trailer that weighed about a ton that we were pulling. When he hit the brakes he couldn’t stop because of the gravel, so he took the other lane – but there was a car coming! So he took the ditch and the trailer unhooked. I looked behind and it was flipping! And Will ended up going through a farmer’s yard at 60 miles per hour and killed a chicken. The farmer came out with a really forlorn look on his face. Will jumped out of the car, said “I did it. Do you have a phone? We’re late. I gotta get a tow truck…”

The Walkers were a more democratic institution than it may have appeared. True, MacCalder had his name before the band, and ended up being the primary spokesman and interviewee. But he welcomed all writing ideas from any member. MacCalder in particular enjoyed co-writes as they added variety to the song list. And even though he ended up singing lead on most songs, he welcomed – indeed sought out – band members who could sing up front with different styles. He wanted to be the leader, but he also enjoyed it when other band members stepped into the spotlight. Dann looks at it this way:

Will would be the catalyst. He’s the guy who fired everybody up and got everybody going. He had the idea… I’m not so sure he shared it. And he’d probably be the first guy to say, “Yeah, I didn’t do it right,” but everybody else was like a tool, and he was just using us—not in a detrimental way, but he was…the music… I had other things to do. I was a big believer in showmanship and things like that, so I did that. We were always doing things on stage.. but again, I helped out the best I could.

The Walkers also started to release their recordings to the public. Three of their four singles hit the market that golden year 1967. The first “Diamonds and Gold” b/w “Baby Do You Need Me” (both penned by Will MacCalder) came out in March to rave reviews. The Journal:

Congratulations to Capitol Records for finally releasing the Willie and the Walkers disc, Diamonds and Gold. This record is really something. Rather than just swimming around in slurpy superlatives over the Bill MacCalder original, we’ll just say one thing – we like it. Very, very much.

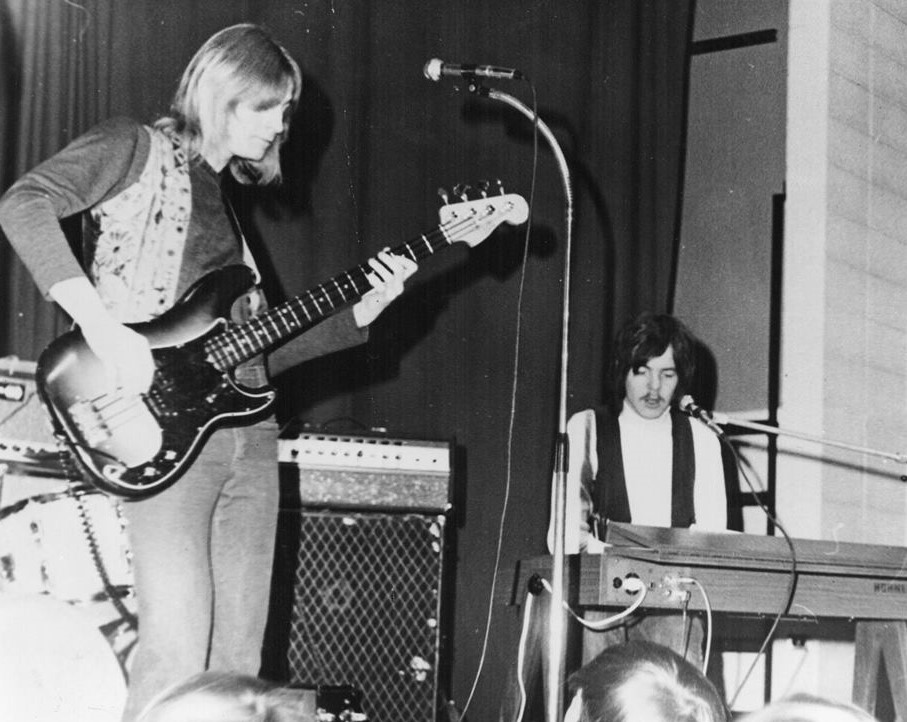

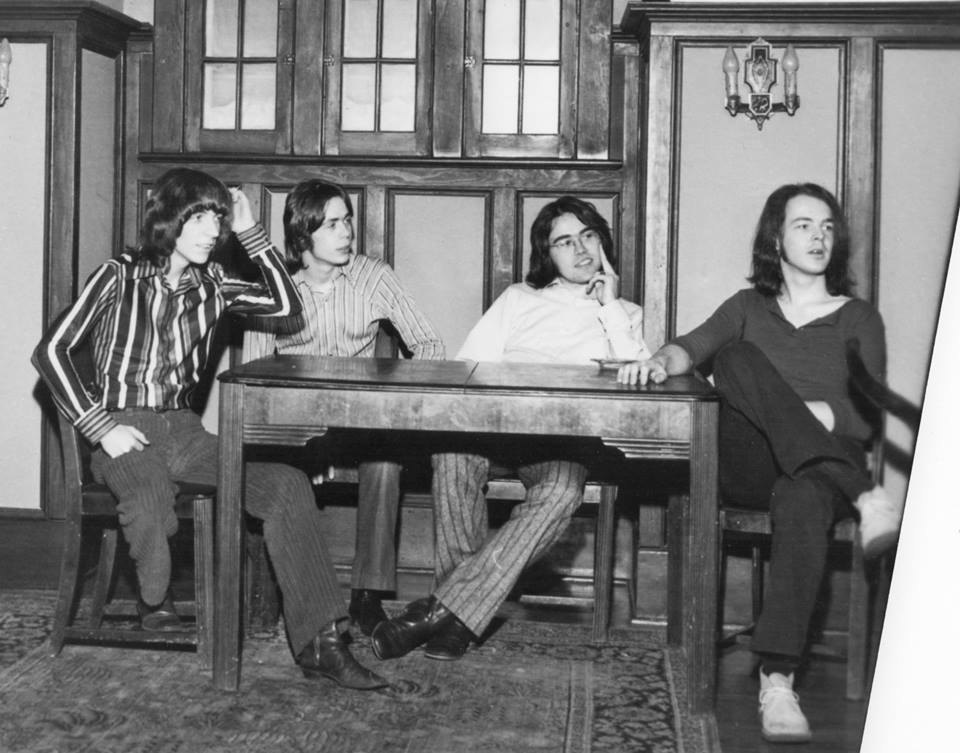

photographer unknown, courtesy Provincial Archives of Alberta, PR1992.0180

Capitol took out a half-page advertisement in RPM in April with a group portrait and the heading “The Walkers Are Running Up Chart Listings!” “Diamonds and Gold” entered the R.P.M. Canadian chart at #14 (and the general chart at #99) during the week of May 6, reaching its highest point at #3 during the weeks of 17 and 24 June. It was a strong debut, and Bill Hardie recalls that it got fairly heavy radio play in Vancouver and the lower mainland, as well as in Saskatchewan. It is a mystery as to why Petruk’s “Just Don’t Pretend” did not make it on the b-side, although he was no longer around to advocate for it. It is a strong composition with a driving performance, and fits perfectly into the band’s early oeuvre.

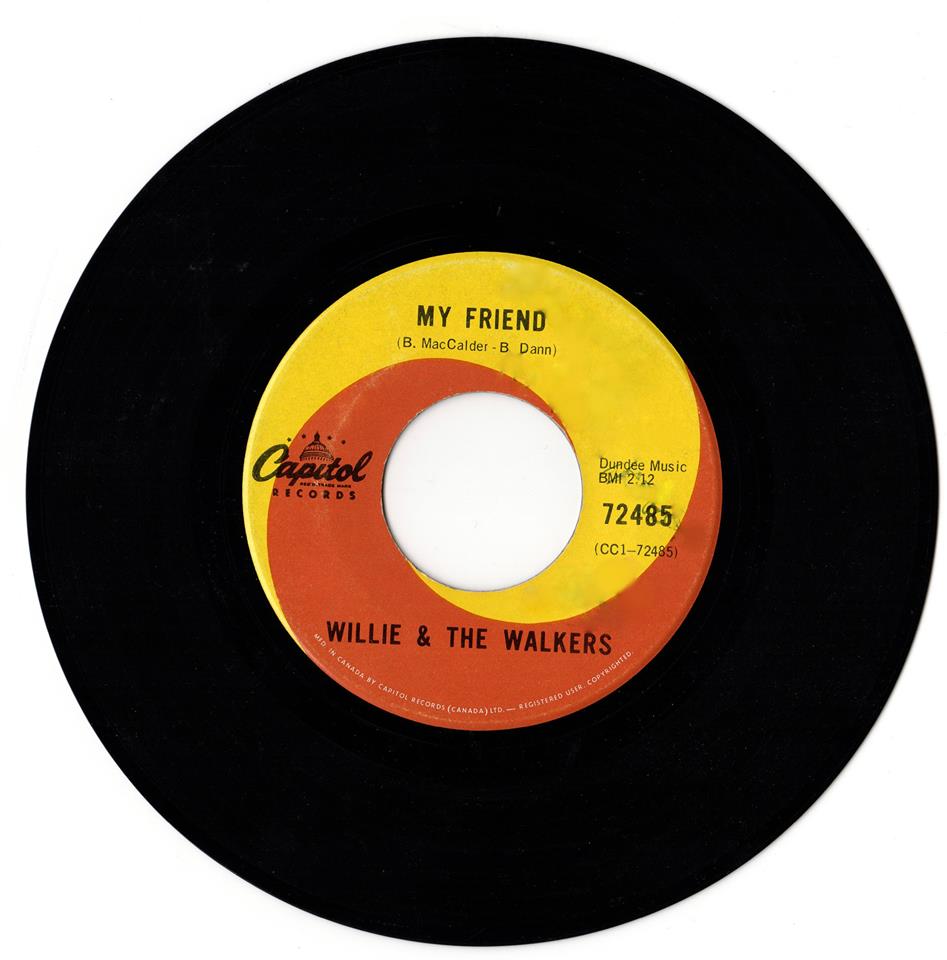

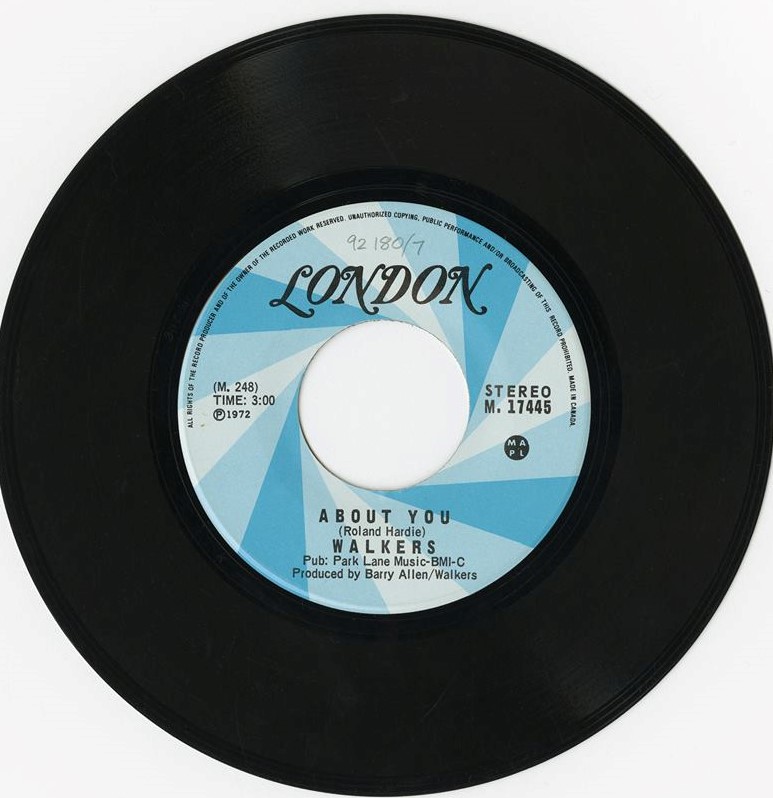

The Walkers released their second single on June 1, 1967. “My Friend” and the B-side “Is It Easy To See” were both written by MacCalder and Bob Dann, and were again recorded in Clovis with Norm Petty producing. “Easy to See” was a slinky Chris Montez-influenced number that could easily have come off a Zombies album. This second recording session resulted in six original tunes, and opened up new worlds for the band. They experimented with new instruments: “The Magic In Her Eyes” used a dominant sitar lead line by Dann, while “The Door that Leads to Nowhere” incorporated a drum machine (at that time outlawed by the Musicians Union) behind Rolie Hardie.

Norman made us feel really comfortable. He was such a calm, cool, collected guy. And he was so into us having fun. He wouldn’t change our arrangements – he’d encourage them to “grow.” He didn’t want us getting too self-conscious or thinking too much….we were delighted to be there – we knew we were in the hands of a real producer.

Nelson agrees:

I had never been around a real producer. He was also a writer, so he had a wise and measured hand in helping us hone our studio chops without being overbearing. Norman was an intriguing and very kind, a soft-spoken Southern gentleman. He was obviously loved and well-respected in that community and the bands he’d worked with were never far away from Norman. During my two jaunts with the band in Clovis, I got to meet and hang with Jimmy Gilmour and the Fireballs, the legendary George Tomsco, and a couple of members of The Champs (the “Tequila” guys). Norman had framed gold hit records all over his walls. He co-wrote a number of Petty-Hardin hits for Buddy Holly including the best-known ones. I was too young and stupid to know that I had lucked into a piece of rock history at that point.

He continues:

I hadn’t thought of myself as a writer at all, but on our second trip to Clovis, it was decided that we needed to write our own material. I mean, we went down there with at least two or more covers to record, and I’m guessing Norman thought it was not going to help the band to record covers. So we were all asked to try our hand at writing while we were there (a week or less). So, Bob Dann and I wrote at least one song together and I came up with a couple more in addition to Willie, I think who wrote at least one more there. Anyway, Norman got us to rehearse and record whatever was ready, and I managed to get three of my on-the-spot tunes recorded.

As well they did “Appreciate a Girl.” Dann remembers:

I …remember Will himself and Norman Petty asking me to do a guitar solo in one of the songs. Which song is it? —it’s one that Will wrote himself. He said, “Put a guitar solo in it,” and I said, “Well what do you want?” He said, “It’s up to you!” So you’re sitting in a studio by yourself and they’re playing this track back to you and what do you do? I don’t know to do this…I just started to play with my fingers. “Who did that?… I probably did about three tries on it, and they said, “That’s great; leave it the way it is.” It was a little too fancy the first time. I remember Norman saying, “It’s a little too much at the end. Make it a little simpler,” and I tried it the second time and it wasn’t quite right, and they said, “One more time,” and we did it, and that was it. Three tries. The amazing part that just shocked me was that it just happened… That song was later recorded, and I heard it on the tape that Will had given me. Jimmy Gilmer and the Fireballs did it as a B-side or something. I don’t know if they ever released it, but they did re-do the song, and the guitar lick George Tomsco plays is identical to the one that I played. It’s the highlight of my life—that’s it.

The sophomore effort was not as successful as its predecessor. It entered the RPM Canadian chart on July 1st with a supportive introduction: “Willie & the Walkers have released another single on Capitol. This one “My Friend” is a strong follow-up to “Diamonds and Gold” and could give this popular Edmonton group another crack at the national scene.” Unfortunately it did not take off, and was only on the R.P.M. chart for three weeks that month and did not rise above #13. Canada Bill, the anonymous correspondent in R.P.M. pushed it strenuously, calling it “a really great record. I hope some of my real Canadian personality friends will dig up their copy and give it a spin.”

Capitol Records, 72485, author’s collection

The band played a number of interesting gigs that summer. One was a rousing multi-band extravaganza held on August 21 at the new Edmonton Gardens. It was one of the stranger combinations of acts. The Who, the Blues Magoos, and Herman’s Hermits (Herman was somehow the headliner) were nearing the end of a three month North American tour, with the Canadian dates including Calgary and Toronto in July, and Edmonton, Winnipeg and Fort William (now Thunderbay) in August. The Edmonton performance added Willie & the Walkers and the Guess Who. As would be expected The Who completely stole the show, both with their volume, and their on-stage behaviour.

The Edmonton Journal sent two writers to the show – one adult and one teenager. Barry Westgate was ostensibly the adult, and tried to dismiss it out of hand:

The Who break up their instruments at the end – and that’s a grand idea. The Blues Magoos peer out of a wild cacophony of electronic mayhem they call “total re-creation” music. No words are intelligible…just amplified madness. And for this the kids still screamed Monday night when more than 8,000 gathered in The Gardens for another helping of the gigantic hoax called teen-age entertainment.

Nelson’s memories are dominated by the teenage reporter Lori Ball and his co-interviewee Randy Bachman;

I particularly remember this date because an Edmonton newspaper entertainment scribe named Lori Ball wanted to interview someone from each group. I guess Willie didn’t want to do the interview (knowing what going up against Randy Bachman would be like?), so I was nominated to do the interview. When Ms. Ball began the interview until it ended it was 95% Randy – with me barely getting in a word, but I was fine with it. ….I was interested to hear Randy speak, but there was no “off” button…

In the end, it was all for naught: Ball’s review several days later made no mention of either The Walkers or The Guess Who, and contained no quotes from either Bachman or Nelson.

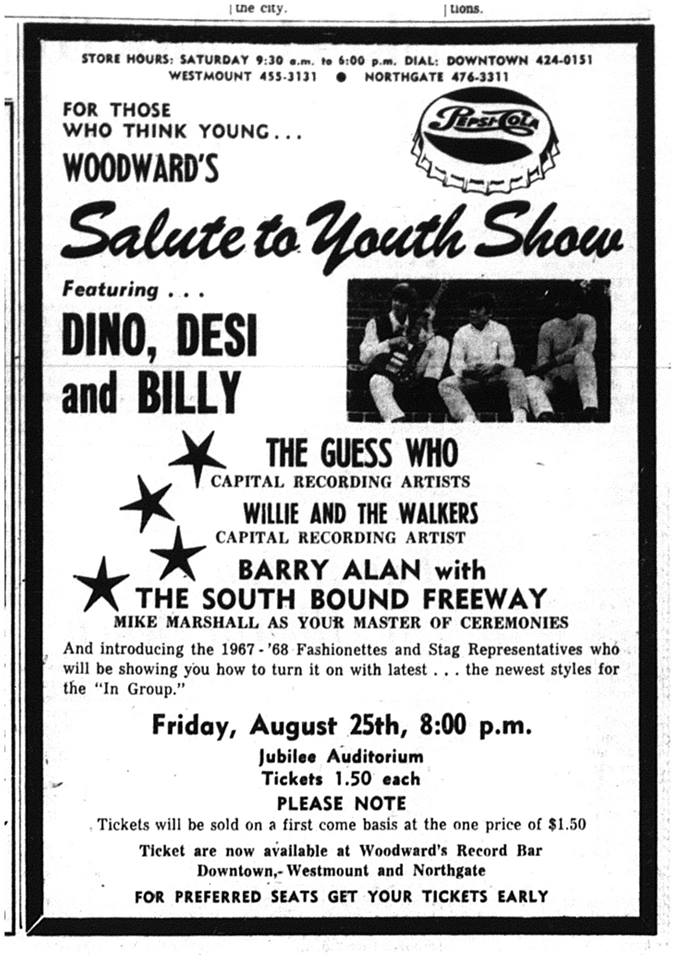

Two days later, The Walkers and The Guess Who teamed up with the hyped-up American group Dino, Desi & Billy, to play back to back concerts first at the Calgary (August 23) and then the Edmonton (August 25) Jubilee Auditoria. Both venues were comfortable, classy spaces, each with well-engineered acoustics and 2,500 seats on three levels. The Edmonton concert was subsumed into a larger “Woodward’s Salute to Youth” city-wide event with fashion shows and back-to-school displays. It also saw the addition of their friends Barry Allen and his then backup band The Southbound Freeway.

Nelson recalls:

Dino was the first son of Dean Martin, Desi was the son of Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz, and Billy Hinsche was the son of one of the major realtors in southern California. They were a 1st level ‘bubblegum’ appeal, but musically weren’t that bad for a very young trio. I actually got to spend some time with Desi Arnaz, Jr. the day we were in Calgary, and I found him to be a very down-to-earth and personable guy. He and I got along very well and I remember cracking him up. Both of us began riffing with stupid accents and jokes, etc.

By this time Nelson realized he was in with a special group of guys:

Although Willie was the acknowledged leader and group spokesman, the brothers Rollie and Bill were beautiful, down-to-earth people, children of a wonderful relationship that I’m still grateful I got to see and benefit from. Also, Bob Dann, the group’s lead guitarist was an extremely funny and intelligent guy, always fun to be around. I learned a lot about guitar playing and basic chord structure from him.

He continues:

Rolie was the young guy in the band, good-looking and smooth, and girls wanted to mother him! He was a very tasteful and dynamic drummer with excellent time- keeping ability. His brother Bill was probably the best all-around musician in the group. He understood the mechanics of music and had a deft touch on the bass, great “ears”. Bob Dann was a consummate guitarist, a guy who had studied more than one instrument growing up and was into guitar. He was the guy who nearly went nuts when he found out we were going to be touring with Johnny Rivers because of James Burton being one of Johnny’s two accompanists.

Bryan Nelson decided to move on at the beginning of October 1967. His health issues played a major role in the decision. As well he was feeling under immense stress – he felt he had to improve his guitar playing, he had to write more songs, and he did not want to delay the band’s upward momentum by his health problems. It seemed like a never-ending spiral:

My health was really in rough shape at the time. I had developed stomach problems in my early teens, but by the time I got to the Walkers and all the bad food…I had ulcers diagnosed by a doctor in Clovis…By the time we returned to Edmonton, my stomach pain had worsened, and after struggling for a few more weeks, I asked for some time off. I was barely away for a few days when I got the call from Willie that I was replaced.

According to MacCalder: “Bryan left on the advice of his doctor. He was told he had an ulcer and had to get bed rest.” They felt they could not wait for him. As reported in The Journal on October 13th:

The roll call for Willie and the Walkers has shifted somewhat. Ron Rault has taken over in the vocal department from Brian [sic.] Nelson. The group played a double band-stand last week with The Lords to record crowds. And as all good Walker fans know, there is much in the offing from the group. But more about that next week.

Nelson had given three important songs to the band: “Feelin’ So Good”, “The Door That Leads to Nowhere” (co-written with Dann), and “The Magic in Her Eyes” which were in-concert favourites but which did not make it to disc for The Walkers. Two of them did however make it for other bands. After leaving the band, Nelson’s stomach ulcers healed, and he went on to join the Lethbridge radio station CHEC as a disc jockey. It was there he had a pleasant surprise:.

One night while sitting at the board, I received a phone call from Norman Petty in Clovis. He asked me for permission to allow two of the songs I’d written while on the 2nd trip with the Walkers to be placed to two groups Norman was producing. One was from Denver and they recorded “Feelin’ So Good”, which I don’t think I even have a copy of, and the other was “The Magic in Her Eyes”, both eminently forgettable, in my opinion. But it was exciting to hear Norman talk about it, and of course I gave him verbal permission. He told me to watch “Cashbox” and “Billboard” magazines, the indie bibles of the day, to see what happened to the tunes. Sure enough, a few weekly issues later, there was my name as writer under the band and song name. I have to admit that I had so little self-confidence at the time that it was almost like looking at someone else’s name. I never even kept those issues! I never asked for copies of the songs that Norman recorded, but I’m sure if I would have had that presence of mind, he would have helped out.

When asked how he regards his three tunes in retrospect, Nelson muses:

At the risk of sounding jaded, I think those tunes were okay considering that I had no precedents at that point for writing songs for a band to record. I had always had musical ideas churning around in my head – I loved listening to many kinds of music – but when put upon to come up with something, I don’t think I did badly. My voice on “The Door That Leads…” sounds almost pure, achingly devoid of affectation or, frankly, substance, but again it was not a bad first try. The funny thing about that song is that Willie called me once to tell me that Capitol Canada had decided that the next single should be that tune. He called me for permission to go ahead with that although by that point I’d been out of the band for at least two or three months. What a spot that must have put them in….

Nelson looks back with mixed emotions. He left no better off financially: “I was given zero cash for my time in the band, hadn’t made any money and only received the daily stipend for food allowance, etc.” Still he grew as a musician and songwriter, and overall had a good time: “I was really a passenger in so many ways in those days, but it was fun to be a part of something that was musically successful. We got asked to sign lots of autographs, records, casts (lol), and so forth. It was a lark.”

MacCalder made a brave decision to add Rault to the lineup. He was a talented and unique vocalist, and brought a very different musical sensibility. He was also the polar opposite of the agreeable and affable Nelson – he was an opinionated, frequently ornery rebel, who thought everyone in the band should have equal say in everything – but especially him. Rault was an old friend from the Bonnie Doon neighbourhood. He had established himself as a singer of note in the band Tyme V (or Tyme Five). In October 1966 he jumped to a more professional group Time Machine (although he did not overlap with Bob Dann). It was a combo that was appreciated by all other musicians, but not particularly by audiences. It included in its ranks Al Treen and Bruce Nessel (formerly with Graeme and the Waifer), Steve Palmer, and Ken Branson. According to MacCalder:

Ronnie had a profile, as well as black, gravelly vocals. His was just a different tonality – for instance he took over “Georgia On My Mind.” He was also a lively front man – he did Otis Redding stuff, Rolling Stones stuff – things like “I Don’t Need No Doctor” by Ray Charles.

The Time Machine were certainly a groundbreaking band for Edmonton – if only in their repertoire. Rault:

…at first we were doing a mix of British versions of R&B, and some R&B from the States. Al Treen said one night “We’ve got to start looking at this stuff, because nobody else is doing it.” He played us some Junior Walker, and James Brown. This was the first time I had even heard of James Brown, and he put it on and I just lost my mind. I got on the microphone and I was just singing and I thought, “I’ve gotta make those noises that those guys make,” and all of a sudden I hit this falsetto note that was out of this world—I didn’t even know where it came from. It sounded like the high register of a saxophone, like it was beyond my vocal range, like, “I can’t do this!” And all of a sudden it was there. Al Treen stopped everything right in the middle and put his arm around me like, “My boy, my boy” …. and all of a sudden the band was “This is what we do.” And we started doing Wilson Pickett, Otis Redding, James Brown…“99 and a Half”, “Midnight Hour” of course, “634-5789”—that was a big one. A lot of Wilson Pickett. “Mustang Sally” of course. “Shotgun”, “Shake and Fingerpop” by Junior Walker. “Shoot Your Shot” by Junior Walker. The real rockers by those guys. We just went right into it…. Yes, and we did some blues too. We did T-Bone Walker, “Stormy Monday”; “I Put a Spell On You”, “Hoochie Coochie Man”…“Smokestack Lightning.” Steve Palmer collected, much to his credit, a lot of the blues that I knew at that time. He would go out and look for this stuff. Chess Records, and the earlier stuff, like Lightnin’ Hopkins and Sleepy John Estes and Blind Willie McTell…it was brought into our bloodstream. It was there from before, but now it entrenched itself.

It worked well for a while, but the lack of gigs was disheartening. Just before the group imploded, they changed their name to The Umbrella. A groovy name – but it didn’t help. Rault recalls:

I hadn’t seen Will in six months. He phoned me up at Randy Sawyer’s while we were rehearsing. “Why don’t you come and join the band? We think you’d fill the bill…” I said, “No. But I’ll think about it.” These guys were pretty square. They weren’t hip. So I went in there and told Grant and Randy, “Will wants me to join the band and I said no.” Grant grabbed me like, “These guys are touring the States and Canada! They’re gonna break out right away, they’ve got a hit! Wake up! What are you, nuts?” I went back to the phone and dialed the number, because Will had said, “Well, if you change your mind…” So I said: “Hey, actually I’d like to reconsider that offer,” “All right, well come over…” And in a half hour I was over at the Walkers’ studio, which was over on First Avenue and Third Street. We were in a little strip mall, and they’d built a studio in it—sound-proofed, headphone plugs, microphones, all on the walls… they had a sound booth in there, two Sony two-tracks in there. Bryan Nelson had been in the band and had gotten such a bad ulcer he had to quit. He was literally killing himself.

A framework had to be established:

What I thought was going to happen—it was very complicated, but Will sort of laid out the business to me, like, “This is what we do, this is how we do it, this is where we’re going.” I said, “OK,” and in my mind I was thinking, “That could change… we’re gonna write really good stuff. Look at all this great material we’ve got, and all this money—we’re gonna have fun.” And from then on, it was a battle of wills between Will and myself. I must have quit that band five times. I kept asking, “Do you guys want to be a hit? You wear these goofy uniforms…goofy cute. They were cultivating that. They wanted to be like Paul Revere and the Raiders. Paul Revere and the Raiders came out in costumes and did all these regimented steps on stage, and played all this straight-down-the-middle pop music. And they were hugely successful.

Although Rault had no designs whatsoever on the band leadership, he was never happier than when he was throwing critical barbs in MacCalder’s direction and encouraging mutiny. He would join the band for their travel-heavy autumn. They ranged far afield in October and November 1967, playing Calgary (Friar’s Den – twice), Cooking Lake (Lakeview Pavilion), Consort, Moose Jaw, North Battleford, Medicine Hat, Dawson Creek BC, and Calgary again (Agriculture Building).

Another notable one was the Centennial concert in Consort, AB on October 21st. A full day’s old-fashioned variety show, it started with the official opening of both the Centennial Caravan train and the Consort Sportsplex, then public recognition of people’s centennial projects, square dancing, tap dancing, a rocket ride for kids – and finally the talent which included the Hannah Band, Beebe’s Orchestra, Jorgenson’s Orchestra, the Lacombe Centennial Singers (100 in number), and finally The Walkers.

Blogger Joe Thornton (“Joe Thornton’s Rant”) recalled it many years later:

…one of my favorite groups when I was just getting out of Junior High was Willie and the Walkers. Picture it – the year is 1967. I was given a free ticket by the Sedalia community association to attend a $100.00 a plate dinner (figure out what 100 bucks was worth in 1967!!) for the opening of the Consort Sportsplex.

The headlining entertainment was Willie and the Walkers – their big North American hit was Diamonds and Gold (one of my favs at the time) – they hailed from Edmonton… the show was great and was hosted by my all time favorite DJ Bob McCord from 630 CHED radio (he sang Los Bravos’ “Black is Black” – backed by W& the Ws)…Didn’t know he was a singer until then.

The show ended way too soon and I was still wanting more. Debbie Kroeger, later to be mother of Chad Kroeger of Nickleback was feeling the same way. She was now a cousin by marriage – my uncle – Claude Thornton and her aunt – Helen Kroeger had just been married a couple of months before. I cajoled Debbie into getting the keys for the dealership (her dad Henry Kroeger – later Alberta Transport Minister – owned the John Deere dealership in Consort) and together we talked Willie MacCalder… into doing an impromptu concert at the shop… it went for about another three hours… it was pretty magical for a couple of 15 year olds – I personally believe that was the real origins of Nickleback!

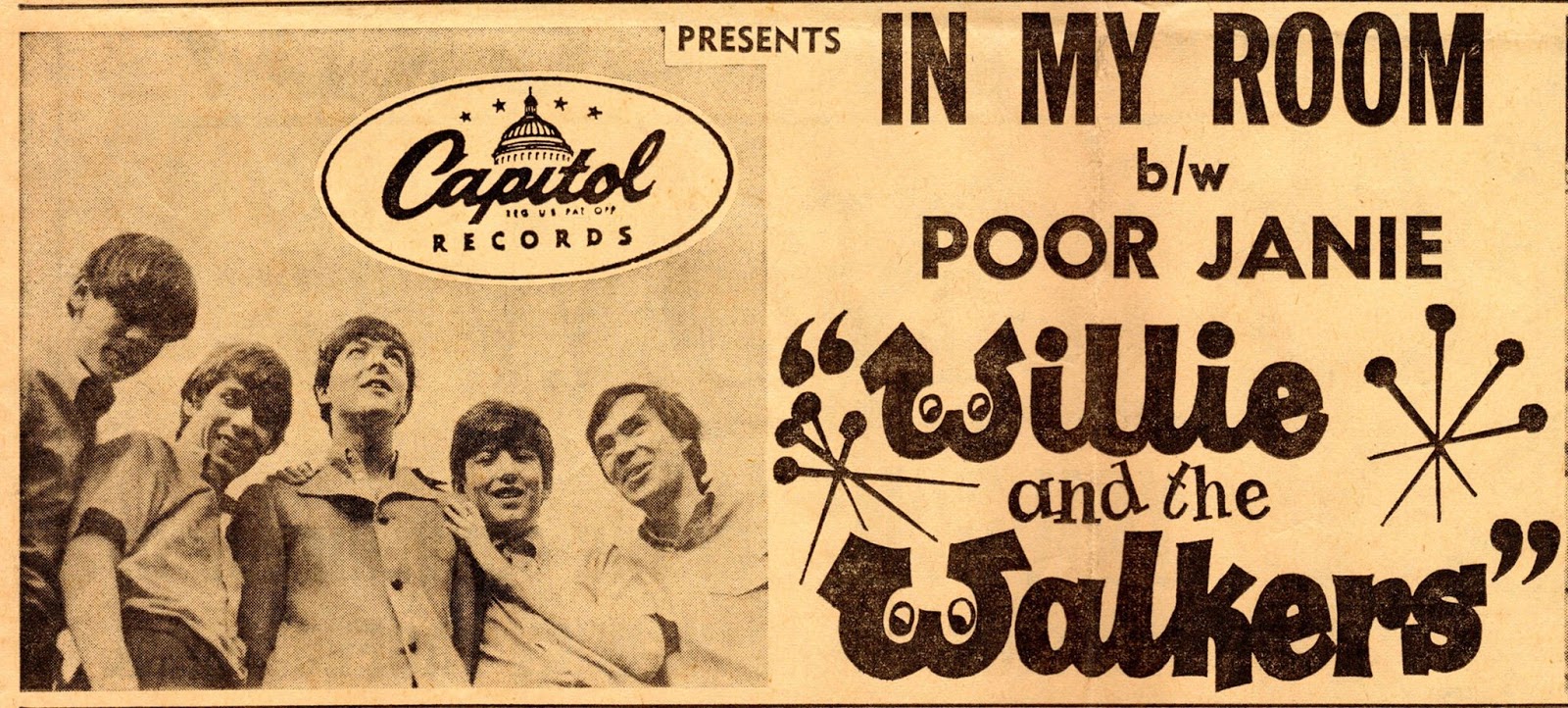

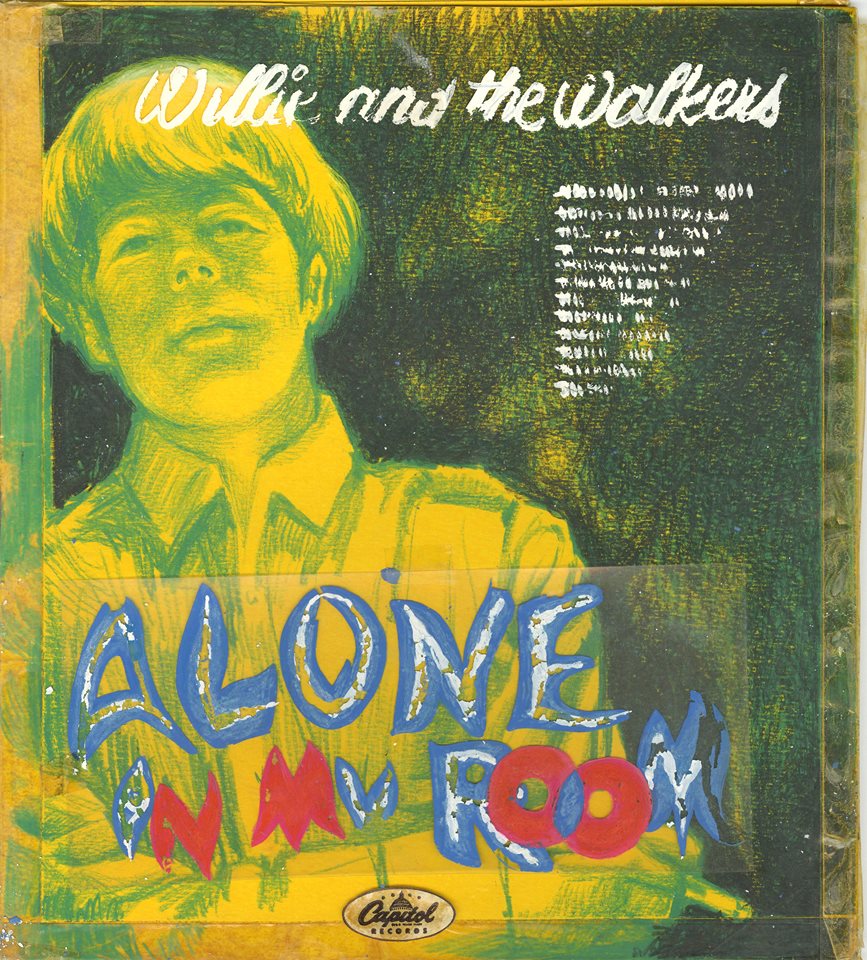

Arguably their finest recording hour had already come with the results of that third trip to Norman Petty’s studio. By this session, MacCalder’s vocals had loosened up. He was obviously more comfortable in the studio, did not feel the need to enunciate every word, was much more expressive, and sounded like…himself. The third single was the extraordinary “Alone In My Room” b/w “Poor Janie.” The A-side was originally an old Spanish folk song, but was turned into an English bluesy soulful exercise by the American songwriting team of Prieto, Vance and Pockriss. It was originally recorded by the New York singer Verdelle Smith (on Capitol Records), and later by both Nancy Sinatra and, ironically, The Walker Brothers. It was unlike anything Willie & the Walkers had done before – prior to this all their songs had been impossibly cheerful and happy. This one was a serious downer – a two verse ode to loneliness, an empty life, and depression. Of course it appealed to any teenager who had been dropped by their first love. Dann knew it was special:

I don’t know if the rest of the guys did. I don’t think they really believed me, because we were looking for another cut because we didn’t have anything good down there, and that’s when I suggested we do “Alone In My Room”. I don’t know if they’ll own up to that or not, but I distinctly remember basically having to sell it to those guys. I know Rollie thought that was a good song. I think overall it was, without a doubt, the best song that we ever recorded. It was clean, it wasn’t messy, and it was the Walkers. The rest of the songs are a little bit flowery, a little bit Norman Petty-ish, but this one was us.

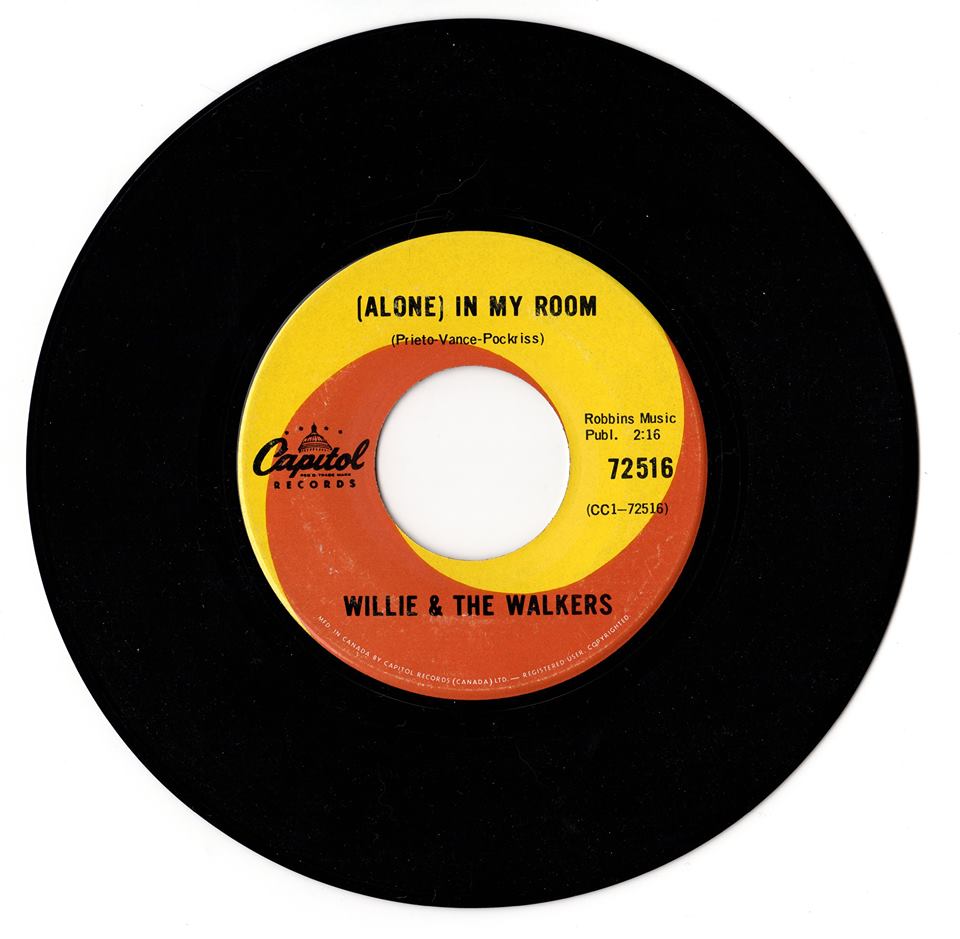

Capitol Records 72516, author’s collection

MacCalder added a hint of a Bach fugue for the opening, and sang with a clear, though appropriately angst-filled voice:

In my room, way at the end of the hall

I sit and stare at the wall

Thinking how lonesome I’ve grown, all alone

In my room

In my room, where very night is the same

I play a dangerous game

I keep pretending she’s late

So I sit, and I wait

Over there is the picture we took when I made her my bride

Over there is the chair where I held whenever she cried

Over there by the window, the flowers she left – have all died

In my room, way at the end of the hall

I sit and stare at the wall

Thinking how lonely I’ve grown, all alone

In my room

“Alone In My Room” took twenty-seven takes before Petty decided they had the best version. The other tunes included two covers “Tired of Waiting” (by the Kinks) and “What Is The Reason” (by the Rascals), as well as two MacCalder originals “Loser” – one of their funkiest and finest workouts – and “I’ve Given Up My Soul” – none of which would see the light of day for almost thirty years. Many years later Bill Shute would review the CD reissue of all the Walkers songs, and made the interesting observation:

…ALL the material from the first two sessions is original. It’s not until the third and final Petty session in October 1967 that any covers are recorded. This is the reverse of the method of most 60’s bands, who usually started off doing mostly covers until they developed their song-writing skills. Perhaps the expense of traveling to New Mexico encouraged the band to bring their A-Game to this session…..The three covers are all first-rate. By this time the band had developed its own sound, and the songs taken from The Rascals, Verdelle Smith, and The Kinks truly sparkle–in fact, the cover of “Tired of Waiting For You” could have been released as a single…it’s that confident and distinctive.

The single was released on 6 November 1967 and not surprisingly hit #1 on CHED’s daily chart the following day. The Journal reported on 24 November “Willie and the Walkers’ disc In My Room has crashed the top twenty in Calgary already and is getting good action down east.” It entered the RPM Canadian chart at #13 during the week of December 2nd. It stayed on for eleven weeks, making it to the top spot on January 20th 1968.

MacCalder remembers this as a special autumn and winter in the band’s history:

It was a dream come true for us…we were kids, too young to have any vices. We were really high on life. I mean, we were on the same label as The Beatles and The Beach Boys! We’d drive around to all these prairie cities and towns and all the stations would be playing us. We were hearing it everywhere… It was #1 on all these charts. For us it was a very big deal.

The Walkers’ popularity started to grow as they travelled further afield. In the first week of December 1967 they played a number of showcase gigs in Winnipeg, most notably at J’s Discotheque, at a local dance party at Polo Park Shopping centre, and the St. Louis Youth Centre. Gary Hart of CKRC immediately started to spin their disc on his show, and made The Walkers the “Star Story” in CKRC’s “Young At Heart Chart” in the Winnipeg Free Press for December 9th. He added: “they proved to all dance types that they had a sound to sell. The group’s new Capitol outing “In My Room” is currently enjoying excellent success wherever it’s played.”

They taped an appearance on CBC, lip-synching to “Alone In My Room.” Ron Legge, a disc jockey/writer for the Free Press was mightily impressed by them, but was also aware of their context:

Edmonton has long been under-rated as an entertainment centre but it’s voice is being heard now through such channels as The Lords, the Southbound Freeway, the now defunct Rebels, and early December visitors Willie And the Walkers. These bands’ formula of professionalism is turning into a solid rock recipe for many “Peg acts who are now realizing it takes more than the shoulder length hair and guitar to be where its at baby… .

During this trip they also ran into a band, The Fendermen (also featuring the “Gorgeous Fenderettes”), who were playing at The Towers Club. Three of the four members were from Edmonton, where in the early 1960s – fronted by Hank Smith – had been known as The Rock-a-Tunes. The two bands become good friends. The meeting would shortly have a far-reaching effect on The Walkers future.

Meanwhile back home, Lydia Dotto continued to sing their praises and let Edmonton know about their out-of-town successes:

Great hopes in the making for Willie and the Walkers and In My Room. The group just finished a gig in Winnipeg and their song is “in” in the East. It’s already charted on over five surveys down there and its still on the way up. A lot of noise is being made about sending them on an Eastern tour and it could easily become more than noise if the song continues to go. I’ve even heard rumblings that the record could be an American breakout. That might be going a bit far right now, but anything’s possible.

“In My Room” dropped into the R.P.M. Canadian chart at #13 during the week of 2 December. It finally reached #1 by 20 January 1968. (It reached #40 on the general chart the following week).

The Walkers finally got their first nod in Billboard – the music industry’s most prestigious trade journal in November 1967. It was short, and read simply: “Big Edmonton group, Willie & the Walkers, have their third Capitol single out, the Verdelle Smith hit, “Alone in My Room”” – but the point was that they had been mentioned in an international context.

The band’s importance was starting to be recognized by the industry and, in particular, their record company. That and the fact that MacCalder was known to have been talking to a number of labels including United Artists Records, made their head of A&R realize that he should be paying more attention to his prairie artists. Accordingly he decided to check out the action in their home town. In January Billboard reported: “Paul White heads west mid-month visiting Capitol artists Barry Allen, Wes Dakus, and Willie and the Walkers in Edmonton, touring the city’s new studio, and scouting new talent.”

The Winnipeg Free Press reported on 27 January “our friends from the west, Willie and the Walkers, proudly announce their song In My Room as Canada’s top single-seller for the past two weeks.” The #1 ranking finally brought Willie and the Walkers to the attention of the American music industry. Lydia Dotto reported in the Journal on 13 December 1967 that:

Happiness is success. Or vice versa. This being so, one must of needs deduce that there are a couple of happy Edmonton bands around these days. Take for instance, Willie and the Walkers. The threat of national U.S. distribution of In My Room looms large over them, and are they worried? I should say not. That’s not the kind of threat they’re likely to get upset about. Actually the Walkers signed with United Artists Records this week, with the happy result that their single hits the American market in January. UA is planning a big promotion program to get the record going and who knows – with enough crossed fingers here at home, this could be the start of something big, as the saying goes.

The year ended on two high notes. First – their ambitions whetted – they decided they wanted to try and crack an even bigger market. The Journal reported:

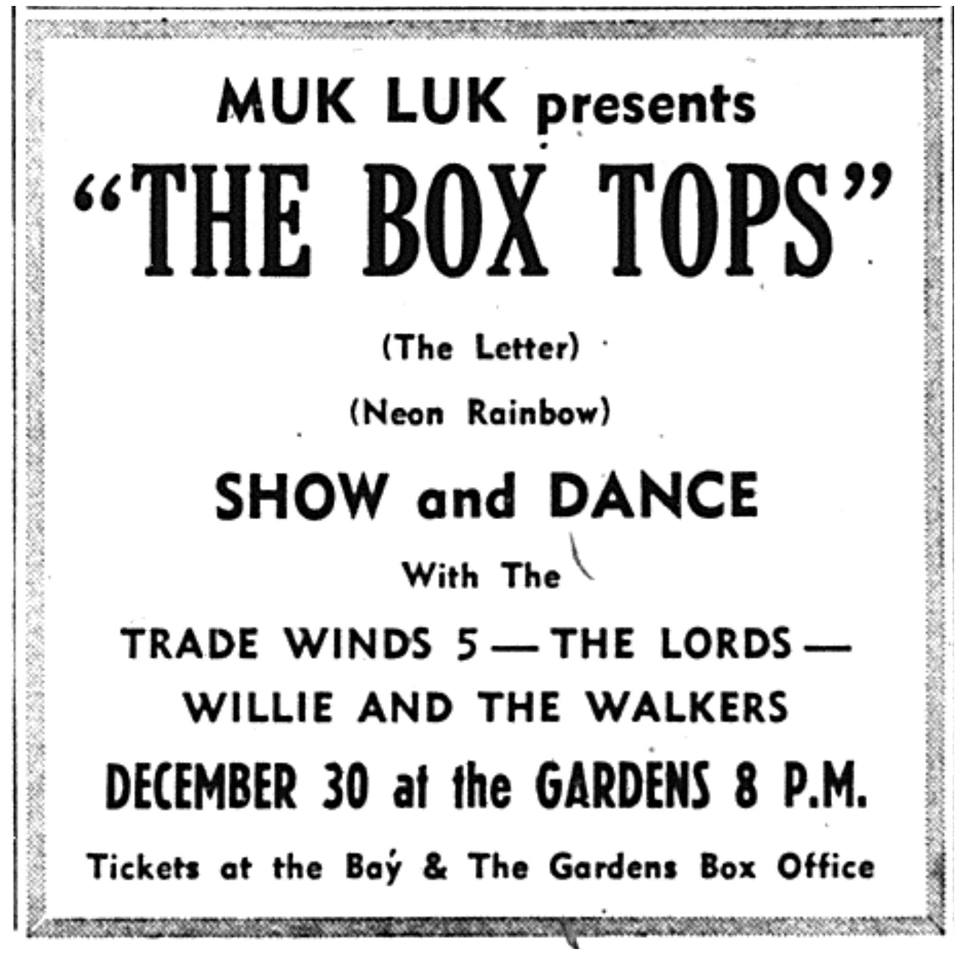

Willie & the Walkers make the headlines again this week. Nothing but good news about them. They’ve been booked to do a U.S. tour near the end of March 1968. At the time of writing, no definite dates or cities have been specified and negotiations are still going on, but it looks like the Southern states got the nod…I’ve heard various enthusiastic comments just this past week about The Walker’s stage act, which is superlative. They’ll be playing the Boxtops Show both here and in Calgary.

One of those concerts which marked a turning point in the career of the band took place on December 30, 1967 when the Walkers opened for The Boxtops, an American band best known for its international hit “The Letter.” Also on the bill were the Trade Winds Five and The Lords (later Privilege). Although the Edmonton Gardens was cold, the acoustics less than suitable, and the audience somewhat lackadaisical, the show brought home to Edmontonians the fact that they had real stars within their own community. Lydia Dotto in particular was impressed, and mused in her column that the imported talent was not all that impressive. The Trade Winds Five were a “study in monotony” while the Boxtops performance was “marred by sound difficulties and two totally unnecessary go-go dancers who merely disrupted an otherwise passable performance by the lead singer.” She continued:

It left me with the realization that our home grown talent has real class. I refer, of course, to Willie and the Walkers and the Lords, indisputably two of the top bands in town. To my mind, the Walkers were definitely the highlight of the evening, the Boxtops notwithstanding. The Walkers put on a very smart, professional-looking half hour show. I recall an interview of a year ago in which members of many top bands agreed that Canadian groups lack professionalism. It was easy to see, at the show, that a lot of work has been done in the past 365 days. The Walkers were very alive on stage, without overdoing it, and they looked like they were enjoying themselves. And then there’s always little things (like a hit record) that colour up the act too.

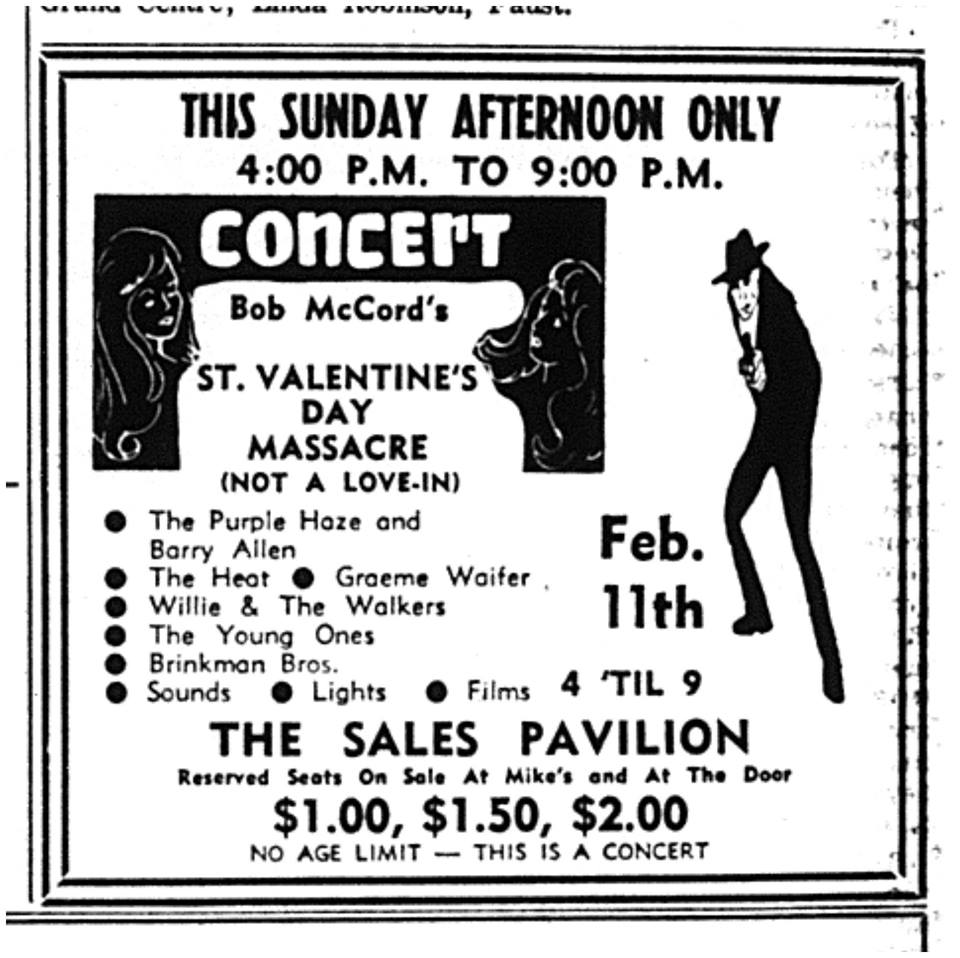

The first three months of 1968 saw The Walkers play a number of important engagements. They started to be booked regularly at Edmonton’s Rainbow Ballroom, they played at the University of Alberta’s “Bust Out” Dance on January 19th, they took part in several multi-band extravaganzas such as “The St. Valentines Day Massacre” on February 11th (with Graeme Waifer, Young Ones, and Brinkman Brothers) and “The [2nd] Mukluk Mardi Gras” on February 16th (with Witness Inc., Privilege, and Purple Haze). They also opened for The Who a second time on March 2nd, again at the Edmonton Gardens. The lineup for that show included Winnipeg’s Sugar n’ Spice, and local bands Warp Factor, The Heat, and the Young Ones.

As promised United Artists released “Alone in My Room” in January, and it did start to receive attention in the U.S. Their first mention in the other American trade magazine – Cashbox – came on February 10th. Its reviewer clearly liked the “rhythmic throb behind this piece of blue-eyed funk a la Procol Harum. The lid is a low-down organ showcase with some interest nabbing vocals. Good teen side that could take off….”

Riding on the high of the last single, the Walkers decided at the turn of the new year 1968 to reach for the next rung of the ladder – an album. The original plans called for bringing together all sides from their three singles, the best of the unreleased material already in the can, augmented with a batch of new material. They had recently been listening to single releases by fellow Edmonton bands The Sons of Adam and The Lords. Their respective tunes “The Thinkin’ Animal” and “Blue” had both been recorded with producer Gary Paxton. Paxton had moved from Hollywood to Bakersfield – about one hundred miles north of Los Angeles – in mid-1967 to get away from his pop roots and delve into country music.

Paxton opened a studio in an abandoned bank building at 1301 N. Chester, assembled a core of crack session musicians (including members of Nashville West such as Clarence White and Gene Parsons – both to shortly play with the Byrds), and started a label called Bakersfield International. The initial hits from the studio came from the Gosdin Brothers, Gib Guilbeau, The Spencers, Larry Daniels & the Buckshots, and of course Paxton himself. As promising as it sounded, it was to turn out to be a torturous and ultimately unsuccessful endeavour for The Walkers.

Recalls MacCalder “we wanted to try something new. We wanted that punchy sound coming out of Bakersfield.” Accordingly, in March the band (along with Dakus and Barry Allen) drove down to California to record. Even though they had not assembled a group of new songs, they decided they were ready to go. MacCalder recalls the first wrinkle: “I said, “I’ve got enough money to get us down and back”, and Wes said “Okay that’s fine…the sessions will be taken care of under my production company. You won’t be paying for studio time.”

Dann recalls:

I think it was more of a holiday than anything else. I think Will will even attest to that. I think we had just had enough of playing, and we just had to get away, and we had to get down to the States… I think Will just did it to get the group away on a vacation. And that’s what we did. We got our 8mm camera and we got our camper and we went for a couple of weeks… It was great….We stopped in Seattle and had clam chowder and met his dad or something like that, and everybody got into smoking pipes. They were 20 years old, 19 years old, rolling down the road with pipes in our mouths, looking real cool! Burning our tongues from smoking pipes twenty hours a day… .

Rault recalls:

…around the spring of 1968 it was time to go do some more recording. “Alone in My Room” had been a hit and we were gonna follow it up… Along came John Wesson, who was hanging out, and who had played with Will before, and I knew JL because I had gone to school with him… Turns out he’s a musician too. As we’re loading up the camper and the trailer, JL jumps in, bag in hand and says, “I’m going too.”… and we proceed down to Bakersfield, but we end up first in Haight-Ashbury. We had to go to Haight-Ashbury, because it was hip. We ended up in a store … just down the hill from Golden Gate Park. This is a hip clothing store, this is where the stars shop, and around the corner is the Grateful Dead house. I don’t know this; I don’t care. I never paid much attention to them—I hated the Grateful Dead when they first came out. I thought those guys were awful – but they were hip!…. .

He cringes (and smirks) as he tells the rest of the story:

… and in walked the Grateful Dead— Bob Weir, Pigpen, and someone else… it might have been Phil Lesh, I’m not sure. I didn’t care. So I’m embarrassed “Oh you kids are in a band?” “Oh yeah, yeah.” “What’s the name of your band?” And I’m thinking “Don’t tell him—make one up.” “Willie and the Walkers” “Willie Wonka?” “No, no, Willie and the Walkers.” “Oh, because you know there’s a children’s story, Willie Wonka and the Chocolate Factory – wow what a cool name…” I’m embarrassed for all of us, because Will is so square that he can’t help himself. “We play all the hits. You know the Ohio Express? The 1910 Fruitgum Company?” He was so square then! We covered the Top 40 on the radio. That’s what we did. I remember singing, “Incense and Peppermints”, and I thought, “Now we’re getting somewhere.”

Lydia Dotto reported in The Journal:

Willie and the Walkers are down in Bakersfield with Garry Paxton, working on some new material. This has caused another delay in the release of their album – they weren’t quite satisfied with some of the work they’d already recorded for it. The Walkers are a popular group in town – and justifiably so. It is commendable that they want to do a good job on their recording. It is also true that a first album is an important and vital step in their career and it should be taken with care. But I can’t help but wonder if the fans aren’t starting to say “promises, promises, promises …”

The first hesitation was the studio itself. Paxton was using an odd setup – the recording area was in an old bank building, while the control booth was outside in an abandoned school bus. The room was painted black with black egg cartons on the wall, and one red light. Cracks MacCalder:” we went from pretty high tech at Norman’s studio to this whorehouse!”

Even so, the recording equipment was state of the art. Paxton was using a prototype eight track multitrack before it was commercially available. Although they started well, the sessions bogged down quickly. Unlike the rapport the Walkers had with Norm Petty, they and Paxton did not seem to understand each other at all. The necessary chemistry was lacking, and as Hardie puts it: “Paxton was one of the strangest dudes I’ve worked with in my life. I just couldn’t connect with him at all. The feeling was just not there.” MacCalder elaborates:

We would sit for an hour and a half outside the studio past the appointed time for the session and still no Garry Paxton to be seen. An hour and a half after that, he would show up and postpone the session until six hours later. When he was finally willing to work, we’d be burned out…. He didn’t like the stuff we came down with, as opposed to Norman encouraging us to get what we could out of what we had written. Paxton would just say “Nah, screw that tune – here, record this one.” That tune ain’t workin’ – here’s one my wife wrote.

In all seven, possibly eight tracks were put to tape in various stages of completion, with none ready for a final mix-down. One was a MacCalder-Rault original entitled “Is It Love”, another was a cover of the Buffalo Springfield tune “Bluebird”, and one that still rankles – Paxton actually forced them to record a song by his wife called “Nature’s Child.” As well Bill Hardie remembers doing a Beatle song “rearranged a la Vanilla Fudge” (he just can’t recall the title).

Then it started to get ugly. Dann recalls the treatment Paxton gave their version of “Bluebird” and its complete lack of subtlety:

We did a Buffalo Springfield song. Anyways, the toilet flushing sound, he put in it, Paxton did. I think he did it just because he didn’t like the Buffalo Springfield. Again, it’s another one of those …things where, “Well, it’s not my label, I don’t give a shit.” Let’s just put a flush at the end of it. And it’s right in the song…And actually we ran one of the voice tracks through a Vox amplifier that had a vibrato built right into it, and all I remember is running behind this amplifier and Gary Paxton saying, “Now,” and turning the controls like this, and Will’s voice went like [makes vibrato sound]. He’s playing back the playback through this to record his voice, and then the toilet flushed after that. I don’t know if he was saying we were singing like shit…That’s all I remember of that trip!

The problems started when Paxton’s drinking started to take the form of paranoia. Rault recalls:

I think we did six tracks. They all disappeared. We never got even a cut of them. Never even heard them again. He was so wired: we went into the studio one day, said “Come on in, we’re gonna do some mixing,” because we’d pretty well finished the cuts. We didn’t know if we’d finished—if we had something, we’d go, “Is that good? Are we done?” We came over one Sunday morning and decided we had to do some mixing. We came to the door and knocked, about 10 o’clock in the morning. Nothing. Go in the walkway… finally the door creaks open and this guy peers out. “What do you want?” “Gary, it’s us.”

In the fine tradition of Phil Spector, he was brandishing a hand gun. Continues Rault:

I was scared. I said “You’re not gonna shoot me…. he might shoot one of you guys but he’s not gonna shoot me.” Scary. I don’t know what happened after that, because I don’t know if we ever got back inside. I think he came to his senses and wanted to know where we’d been.

Then Wes Dakus injured himself. He was paralyzed for several days, and it was essential he return to Edmonton for medical attention. MacCalder remembers it as a spinal disc problem. Rault has a different story:

And the second thing that happened that was funny was… I was telling you about how we had to run into the bus every time—Wes got so excited to tell us something one time, got up from inside the bus, ran down the stairs to come down and see us, yelling all the time, and wham, he ran right into the doorway of the bus, and knocked himself cold. He had to go home after that. That was it; he was done.

Either way, that is exactly when Paxton demanded his payment for the sessions. Recalls MacCalder:

Then Paxton asked me for money, and I said “…this session was supposed to be taken care of by Dakus’ production company”. And he started running down Wes….and I said “Well I guess we’re out of here”. He says “Yeah, I guess you are out of here, and furthermore if I don’t get my money, you don’t get your tapes. So beat your sorry asses back to Canada you dumb Canucks”. The man was such a pig….salty, rude…

He continues: