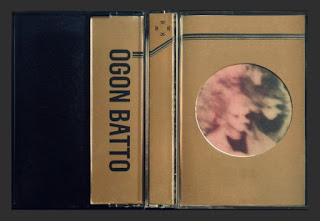

Ōgon Batto

“Accepting time as a filter”

With Hedoro, Ōgon Batto made an album with 29 synth based and Japan influenced mini dramas.

Does the name Ōgon Batto refer to Ogon Bat?

It’s funny, lots of people actually make that reference, which is logical because it’s the first thing you see when you search the web about my project. Although the link to Ogon Bat, which is considered to be the world’s first comic-book superhero, is a cool bonus, it wasn’t the reason to pick this name.

The name is derived from one of Japan’s oldest cigarette brands, called ‘Golden Bat’, in Japanese: ‘Ogon Batto’. I smoked this brand during my first stay in Japan in 2011, and I still do when I’m there. A packet of Golden Bat’s is cheap and its graphic design is amazing. Looking for cigarettes in a 7-Eleven, this thing caught my eye immediately. Later on, facts about the brand’s history popped up and just raised my interest. The brand was part of an economical and political plan Japan had set out during the exploitation of Manchuria (now located in modern China) during the 1930’s and 40’s. Back then, the Japanese secret service had control over the export of these cigarettes, under the rule of the infamous general Kenji Doihara. They had this crazy idea of injecting the filters with opium, aiming at a combination of an imposed calmness amongst the ‘common’ people and making a huge, economical profit. This story made me choose this name eventually.

Why is the album called Hedoro?

Literally, in Japanese it means ‘slime’ or to be more accurate ‘chemical ooze’. ‘Slijm’, which is Dutch for slime, was a working title I used throughout the recording process. Working titles tend to stick with me, particularly this one, keeping track of the vibe I was looking for. I was fascinated with slime since I was a little kid. I watched a lot of horror movies, making drawings of monsters, aliens and that kind of stuff. In some way, slime always popped up. In the 90’s, you could buy these boxed slime toys everywhere, even in your neighborhood supermarket. It was just world’s coolest toy to play with. Up until this day, I’m still intrigued by the concept of slime, its lack of form or evolving state of being. Looking at the way slime moves or ‘behaves’, I can’t stop thinking about these slow-motion scenes you have in nature documentaries: intense, detailed and often with that ominous feeling. And that’s exactly what I was looking for while making this record: emphasising the transformation of a real-life situation or object in its most intense behavior, aiming to describe every bit of it.

You said this record is influenced by Japan.

Traditional and contemporary culture and music of Japan are indeed part of my influences, but I wouldn’t consider it as the general source of impulses. Simply put: during travel, I felt an inter-frequenting buzz on this planet and it happened to be in Japan. There’s nothing more to it than that. I’ve been in Japan a couple of times and it always feels like the right spot to be, digging up parts of its intriguing history and looking at how things are evolving these days. From the start, visiting Japan and having this culture-dive, felt like a double-edged sword and it still does. It’s a country built on rules and spiritualism, with an immediate experience of its real-life contradictions. Which makes it often a complex community to completely comprehend as an outsider. And that’s probably why I like it so much, having this challenge, finding out what I specifically like in relation to this country and using personal experiences to create a more rooted backstory for what I do. I guess there’s one element though, regarding the influence of Japan, which is worth mentioning in a more specific way. Guarding a close relation with folklore, Japanese horror movies often succeed in creating this all-absorbing and remaining effect. In most cases lacking big-budget possibilities, directors are engaged and motivated to focus more on subtleness, manipulating the general atmosphere of a story in a very ingenious way. You get this organic, yet uncomfortable vibe by exploring the minimalism of a mundane situation, recognising its subtleness and turning it into a dramatic experience. This goes for the use of sound and soundtrack as well. Often extremely diverse sounds or styles of music are being mixed, which results in a production, based on non-conformal choices in sound, but still keeping a close relation to real-life, again by using subtleness as an important tool. This solid form of horror changed me, my perception of music and gave way to a new creative approach.

The album’s got 29 tracks, which is a lot. Why so many?

Why not? In the end, whatever the process may be, you’re listening to a record as a whole. For me, dividing a recording process into a great amount of parts or tracks is just a way to explore and archive different elements of an atmosphere in a short amount of time. At the beginning, I tend to work in an amorphous story-telling way, having some sort of narrative in mind but giving every bit of recording its space to move and change, like an organic being. Being open to every vibe you capture is key, because in the long run, combos could work like magic. There’s just this invitation to overkill, I really find intriguing. My computer gets filled up with folders of recordings and sound collages, until you feel a need to stop. It’s this principle that forms the base: record, archive, analyse and figure it out. In the end, it works like a library, open for surprise and selection. And that selection is your final narrative.

Most of the tracks are short ones. Again: why?

Again: why not? Listening a lot to these 2x/3x/4x OST CD’s, I kind of figured out a way of working where every bit of sound can be that track I’m looking for. Diving into an atmosphere for a couple of seconds/minutes and moving on to the next one, initialises this search for diversity in density. Plus there’s a possibility to divide and intensify the focus of the listener in a very clear way. But in general, I feel no specific urge in keeping tracks compact. For me it’s about feeling how much time a track needs to stand on its own.

You only used synths for the making of this record. Why did you limit yourself to synths?

It’s not something I did on purpose and I sure did not experience this way of working as ‘limiting’. I’m just doing what I like. Initially, I traded an old record cabinet with a workstation synthesizer a friend of mine had lying around, about which he said it was partly broken. While figuring this thing out, I found out it wasn’t really broken at all, so it turned out to be a really nice deal. Having this workstation-constructed system of possibilities, motivated me to explore and construct in a very direct way. In contradiction to analogue synths I used before, workstations are specifically designed as huge, hands-on sound libraries. Aiming to digitally eliminate the necessity of hiring an orchestra and grasping sounds from all over world, it does the trick for me. I do not need a lot more, it can be the perfect drama machine.

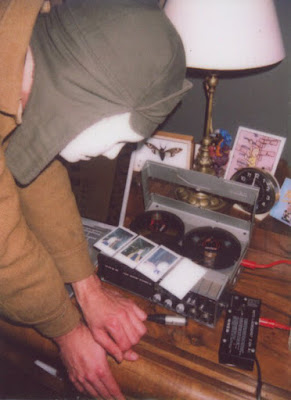

Can you compare Hedoro to 007, your debut tape from 4 years ago?

That tape was the first result of doing something on my own, exploring synthesizers and researching the possibilities and limitations of analogue recording. I got a reel to reel tape voice recorder, went on a trip from Latvia to Japan and created a small auditive library, in no way knowing what to do with this collection of sounds. After some research, I got myself a synthesizer and started to mix everything up, adding some percussive instruments I picked up along the way. Everything was recorded on reel to reel tape or cassette, which at that time really worked for me: doing tape manipulations and experimenting with pitch, speed, loops, etc. It resulted in a minimal collection of spun-out tracks with the fuzzy vibe I was looking for. Releasing it on tape just felt like the way to go. After releasing the tape, I felt the need to extend my view on creating and using sounds, also adding more focus on structure and composition. The Hedoro record gave way to a continuous wave of digital possibilities. Short sound experiments in this way felt fresh and directly transformed into elements of the initial narrative of this record, I mentioned before. Recording a lot more, gives you a lot more options, but it also automatically becomes more complex and challenging in relation to structure. Being aware of that kind of challenge and wanting to make use of it, is something that I would have never experienced without making the 007 tape.

Why did it take you four years to make this record?

Accepting time as a filter really works for me. I like taking my time, listening to projects over and over again. Recordings, adaptations or mixes made during the night – adjusting small details or reworking the whole thing – will make it onto my mp3-disc player, accompanying me on bike rides throughout the city. I really like that combo of meditative repetition and detailed analysation of my own work. In this way, a record evolves continually, bit by bit, until you start to see your own deadline. In my experience, speed doesn’t feel like a useful tool.

The cover of the record is the Rolls Royce statue. Why?

I do a regular hunt for books or magazines in thrift stores, trying to find interesting photos for collages, etc. I came across a book about the history of Rolls Royce and was attracted by its layout and font-use. Flipping through, cutting out parts of cars and again reading background stories, the icon of Rolls Royce: ‘Spirit Of Ecstasy’, became an inspirational entity on its own. This flying female of luxury evolved into an alluring representation of sensuality and erotic beauty, hovering above every track on the record. That said, I have a random esthetic obsession every year, having a really deep interest in things I bump into and just like. For example, doing research on orcas was a thing on my previous release.

You’re also a visual artist. What does your visual art have in common with your music?

When I’m doing visual stuff, creating collages or assemblages is what I like to. And this practical approach is present in my music too: cutting, pasting and working your way to a composition you’re eventually satisfied with. The technique of collage brings forth this great opportunity to combine, and as I said before, it can work like magic. Not sure why, but these two outlets just intertwine. Assembling or reassembling cut-outs of a dozen books for me is the same as selecting sounds or tracks from your personal library and putting them all together into a structure that works for you in the end. Sticking with that basic principle I mentioned before, it’s all about recording and collecting, archiving, analysing the whole thing and finding a good spot for every element.

– Joeri Bruyninckx

© Copyright http://www.psychedelicbabymag.com/2018

Array

Just checked this out on Bandcamp (https://ogonbatto.bandcamp.com/album/hedoro).

Well done