1967 Brit-Psych B-Sides

The mode of the music changed, the walls of the cities shook, rooms hummed harder, ceilings flew away. In his 1965 poem, ‘Who Be Kind To?’, the preeminent beatnik spokesman Allen Ginsberg envisaged ‘nameless voices crying for kindness in the orchestra, screaming in anguish that bliss come true’. Amidst the hallucinatory shangri-la of 1967’s Summer of Love, the potential of that bliss came to visit under the thin disguise of UFO-ria. Tomorrow’s ‘real life permanent dream’, unable to gestate quite long enough to be fully realized, nonetheless appeared tangible enough within those twelve tumultuous months as to plant blossoms within an entire generation’s worth of young minds. Building upon the achievements of the psychedelic pioneers of 1965-66, the British counterculture took flight, penetrated the mainstream, flew too close to the sun in conglomerate homage to Icarus, before falling into a disorganized and acid-fried retreat which by the decade’s end proved irreversible. Yet, 1967’s hippie high water mark, a desperate bid to enact an Eden of peace, free love and not insubstantial drug use before the encroaching tide of violence could destroy the schemes of the cognoscent bohemian dreamers, changed the society which birthed it in a manner few other subcultures have managed. Not just in the U.K, but across the Western world and beyond, the movement unleashed some of the most compelling music ever recorded. So potent was the power of the new exploratory genre of psychedelia that Rolling Stone’s Langdon Winner recalls this all too brief epoch as ‘the closest Western civilization has come to unity since the Congress of Vienna in 1815’.

Under the commanding influence of a certain Edwardian band fronted by a sergeant named Pepper (not to mention an enigmatic piper guarding the gates of this new technicolour dawn) the house of mod collapsed as flower power kicked down it’s decaying front door, paving a novel way with winding rainbow carpet for strange new groups aplenty with even stranger names-Crocheted Donut Ring, Sensory Armada, Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera and Procol Harum, to name but a few. Established acts buckled under the pressure of this torrent of brand-new competition. Sometimes with gleeful enthusiasm, more often with a fair amount of chagrin and skepticism, they found themselves having to adapt to the times or face the prospect of being forgotten. Gone were the days of simple boy-meets-girl lyrical narratives; over the course of the year, the Who would extoll the virtues of deodorant in ‘Odorono’, Cream would compress the essence of Homer’s Odyssey into the three-minute wah-wah workout of ‘Tales of Brave Ulysses’, whilst the love interest in Nirvana’s ‘Tiny Goddess’ is quite literally a little deity by the name of Magdelena. Variety truly was the spice of life during the Summer of Love.

In 1967, British psychedelia was- for the meantime- free of the vitriol and Vietnam- fueled paranoia which burned as rampant as a napalm blaze in the simultaneous releases by American kindred spirits like Jefferson Airplane and The Doors. As David Wells writes, the U.K music scene

‘…spent 1967 wallowing in the dim and distant past. UK bands who employed the word ‘revolution’ were primarily seeking to establish the right to drop out while wearing cavalry red double-breasted Regency jackets and some really groovy crushed velvet trousers- as perfidious Albion dropped in, tuned up and turned out, the imaginations of the nation’s leading pop acts were fired by the indigenous culture that had informed their childhoods on what was still, to use Thomas Dibdin’s phrase, a snug little island’.

The beatific flower children initially charmed the media of Britain’s affluent post-war society. A Pathé newsreel from 1967 is curious and sympathetic in equal measure, framing the youth explosion that year as a historical event worthy of serious (as opposed to mocking) attention, whilst BBC news coverage of the Legalise Pot rally that July even concluded with the newsreader giving a namaste gesture into the camera. Hans Keller, in his notorious May 1967 interview with Pink Floyd in which he claimed to be ‘too much of a musician to appreciate’ their performance of ‘Astronomy Domine’, still reluctantly noted that ‘they have an audience. And people who have an audience ought to be heard’. Even in his attempts to be derisive, he quite accidentally stumbles upon the appeal to the genre, and perhaps even the entire raison d’etre of the hippie movement at large:

‘My verdict is that it is a little bit of a regression to childhood- but after all, why not?’

The result, in a year where pushing musical boundaries became, paradoxically, the new manner by which to play it safe and earn airplay, was that dozens (perhaps even hundreds) of worthy records found themselves buried by the competition of their contemporaries. What was advanced in the preceding months became passé in 1967, such was the rate of sudden musical experimentalism. As was the case during 1966, a surprising proportion of lost psychedelic classics can be found on the B-sides of single releases, the A-side often comprising a deceptively commercial song. Early psych groups hoped against hope to burst into the charts with a middle-of-the-road musical Trojan horse from which they could leap, having earned the confidence, audience, exposure and budget to exhibit their more turned-on tendencies.

What follows is a list of 15 Brit-psych B-sides from the era of the Summer of Love, which reflect the diversity of the genre as the underground lurched from the seedy depths and launched a petal laden coup d’état upon the unsuspecting establishment. Playful, confrontationally unorthodox and- admittedly- often whimsical to the point of painfully saccharine, each of these recordings are nonetheless imbued with the infectiously adventurous spirit of an age where it seemed anything was possible.

To put it another way- slip into your kaftan, adorn your granny glasses and love beads and perhaps even wear a flower in your hair.

‘A splendid time is guaranteed for all.’

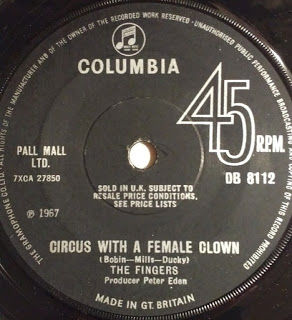

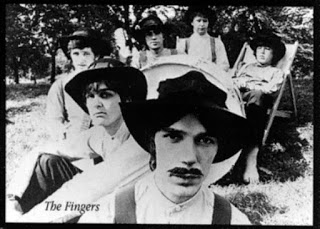

1: ‘Circus With A Female Clown’- The Fingers (A-Side: ‘All Kinds of People’)

A bassist that doubled as a celloist, a melodic yet incendiary live act and a pet monkey by the name of ‘Freak Out’, whom it was claimed produced ‘psychotic smells’: hailing from Southend, the Fingers could well have been created in a petri dish in an intentional effort to capture the gleeful, fleeting pandemonium of the zeitgeist as 1966 ticked over to 1967.

When their third single, ‘All Kinds of People’ b/w ‘Circus with a Female Clown’ was released in January 1967, it virtually vanished amidst a scene congested with innovation, swollen with anticipation, pregnant with promise. An interview with Paul McCartney on January 18th for the pending Granada documentary ‘It’s So Far Out, It’s Straight Down’ seems, in retrospect, akin to an emergency message from an early warning system. Paul, adhering to a similar role as his biblical namesake, addresses the gentiles watching from home on television and spreads the psychedelic gospel of Indica and the International Times, an advanced tip-off that the culture was on the cusp of a seismic shift. The new movement, he stressed, was not to be feared, coming as it was with peace-

‘…so, the next time you see the word, like– any new strange word like ‘psychedelic,’ the whole bit, you know- ‘freak-out music’ and all of that, don’t immediately take it as… because your first reaction’s gonna be one of fear, you know. So if you don’t know anything about it, you can sort of trust that it’s gonna be alright.’

The Fingers’ ‘Circus With A Female Clown’ is as much the opening musical salvo to this new year as anything recorded by their better known contemporaries, preempting many recording tropes that would become increasingly familiar upon turntables nationwide within in the coming months- an atypical title and subject matter (right down to the curious fascination with circuses and vaudeville), Beach Boys-esque harmonies, liberal application of echo, a driving drumbeat, and a hook-laden chorus that tapers off into mysterious, quasi-gregorian chant in a manner not dissimilar to Episode Six’ simultaneous release, ‘Love, Hate, Revenge’.

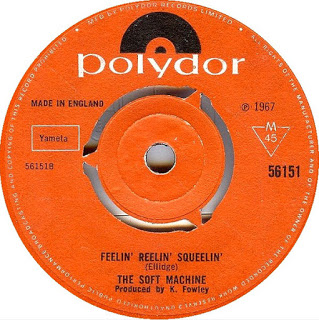

2: ‘Feelin’ Reelin’ Squealin’- The Soft Machine (A-Side: ‘Love Makes Sweet Music’)

Just as Jefferson Airplane’s ‘Surrealistic Pillow’ LP fired the starting pistol for the proliferation of records courtesy of San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury scene, Soft Machine’s ‘Love Makes Sweet Music/Feelin’ Reelin’ Squealin’, released the same month, marked the first time the probing Dadaist tendencies of the burgeoning British underground emerged from the cellars of the UFO club and leapt onto the airwaves- debuting at #34 on pirate station Radio London’s ‘Fab 40’ on February 26th 1967.

Produced by American psych svengali Kim Fowley (who had written the lyrics for Cat Steven’s ‘Portobello Road’ in 1966), the A-side ‘Love Makes Sweet Music’ is fast-paced, comparatively straightforward psychedelic pop. The flipside, ‘Feelin’ Reelin’ Squealin’, however, is more abstract, pointing towards the ‘progressive’ genre that would emerge fully at the end of the decade with Soft Machine at the fore. Indeed, here is a key strand of the famed Canterbury Scene’s D.N.A, ahead of it’s time to the extent that when Caravan frequently performed it as part of their live set as late as 1971 in largely the same arrangement, it still sounded relevant and in-step with the times, an impressive feat given how quickly many of the florid efforts by their compeers sounded dated by 1968.

Together with Pink Floyd, Soft Machine shared the distinction of being considered the UFO Club’s ‘house band.’ Taking their name from the title of a novel by beat writer William Burroughs, (whom bandmember Daevid Allen knew personally) Soft Machine embodied the quixotic blend of intellectualism and psychedelic hedonism that defined UFO’s hip clientele. As John Cavanagh writes, ‘the handful of UFO events crystallized a scene of cross-cultural activity’ whereby visitors rolled the dice as to whether they’d bear witness to performances by Pink Floyd and Soft Machine or projected avant-garde films by Kenneth Anger and Jack Smith; spoken word orations by Liverpool poets such as Roger McGough and Adrian Henri or ‘spot the fuzz’ competitions in which undercover policemen monitoring the decadence would be identified. In short, as Jenny Fabian recalls, ‘You couldn’t have asked for anything better than to be out of your head at UFO.’

3: ‘Through My Eyes’- The Creation (A-Side: ‘Life Is Just Beginning’)

Steady success eluded Hertfordshire group the Creation following their 1966 top 40 hit ‘Painter Man’, with its thunderous riff and the novelty of guitarist Eddie Phillips using a violin bow on his guitar- a gimmick Jimmy Page would later pay homage to/pilfer (depending upon whom you ask) in Led Zeppelin.

‘Through My Eyes’, a doom-laden, murky slice of moddish psych, points to what could’ve been if only the Creation didn’t disband in 1968. Tucked away on the B-side of a single that barely sold, the ghostly harmonies and marshy instrumental breaks in ‘Through My Eyes’ nonetheless rank amongst the most memorable musical moments of 1967 for those who managed, against the odds, to hear them- seemingly an opinion shared by the Sex Pistols, who are said to have included a rendition of this cut within their repertoire during early rehearsals. The lyrics point heavily towards the transformative nature of the L.S.D experience and the resultant acid-oriented evangelism that would come to colour interactions between the counterculture and the surrounding ‘straight’ mainstream. In 1967, to trip on L.S.D was something of a ritualistic experience, a rite of passage by which the young and impressionable would prove they had fully eschewed the grey world of post-war conformity- a notion pioneered by Ken Kesey and his ‘Merry Pranksters’ in the early 1960s and popularized by Tom Wolfe’s account of their journey across America, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Here, the Creation seem to gently tease the listener with what lies beyond that exclusive phantasmagorical veil, a world of ‘things you’ve never noticed before, things you’ve never seen, I’m sure.’ Whether the Creation are apostles for a new state of enlightenment or harbingers of psychic ruin in ‘Through My Eyes’ is never disclosed- yet this jeopardy contributes greatly to this deeply atmospheric, mist-laden track.

4: ‘14 Hour Technicolour Dream’- The Syn (A-Side: ‘Flowerman’)

In the wake of police raids intended to bring the publication to its knees, International Times, the underground paper of choice of the British Underground, seemed to be on thin ice by April 1967. In a last- ditch attempt to keep the magazine afloat, founders John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins and Barry Miles, together with David Howson, Mike McInnerney and Jack Henry Moore, set about organizing a benefit concert to generate adequate funding to allow for the continued distribution of International Times. That concert has since taken on a larger than life presence in collective memory as perhaps the seminal event of the British experience of the Summer of Love- the famed 14 Hour Technicolour Dream at Alexandra Palace.

Here was the spirit of 1967 distilled into one night- a lineup featuring the prime alumni of the psychedelic scene, including Pink Floyd, Tomorrow, the Soft Machine, the Pretty Things, the Crazy World of Arthur Brown and the Sam Gopal Dream to name but a handful. Performance art courtesy of Yoko Ono, who is said to have contributed with her famed ‘Cut Piece.’ An area signposted ‘Banana Be-In’ for partaking in the preeminent in-crowd rumour of the year- that, owing to a misinterpretation of Donovan’s hit single ‘Mellow Yellow’, smoking banana skins could bring about a form of natural intoxication. Even a visibly stoned John Lennon was present to witness Pink Floyd’s now-legendary dawn performance, where Syd Barrett directed sunbeams off his mirrored guitar into the faces of the 10,000 strong audience.

The Syn, in fact an earlier lineup of 70’s prog band Yes, were also in attendance and opted to immortalise the memory of the event on the B-side of their September 1967 single, ‘Flowerman.’ The dizzy giddiness of the Technicolour Dream stains the Syn’s lyrics:

‘At the 14 hour technicolour, yeah

And it’s groovy

Cos they’re showin’ movies, yes they are

And everybody’s gonna be there, yeah

Ah, Suzy Creamcheese gonna be there, yeah

Yes, I said have a Havana

And smoke a banana if you want to

I said, I said

Do what you want to!’

Regulars at the Marquee club in 1967, the Syn earned the affections of pirate radio DJ John Peel, who broadcast both sides of this single on the final edition of his influential ‘Perfumed Garden’ show. By 1968, the Syn had evolved into Mabel Greer’s Toyshop- the final stepping stone on the road to Yes’ 1970s successes and excesses.

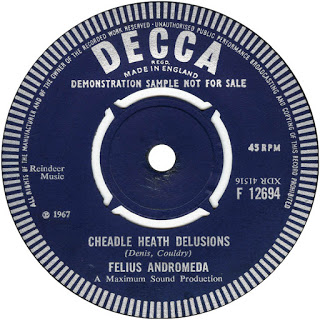

5: ‘Cheadle Heath Delusions’- Felius Andromeda (A-Side: ‘Meditations’)

Where A-side ‘Meditations’, replete with melancholic lyrics and introspective organ, aped Procol Harum’s omnipresent ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale,’ (Recording ‘Meditations’ in a North London church, Felius Andromeda even adopted Matthew Fischer of Procol Harum’s propensity for dressing in monks’ cowls and robes for their promotional material) ‘Cheadle Heath Delusions’- named mysteriously after a Stockport suburb that isn’t even mentioned in the lyrics- features earthen stream of conscious angst over a series of perceived wrongs, including ‘public houses with no beer,’ written and provincially sung by Dennis Couldry, ably reinforced by serenading strings.

Felius Andromeda piqued the intrigue of Johnny Walker, who played both sides of this single as his ‘pick of the hour’ on Radio London, and Terry Doran of Apple Corps; nonetheless, the group failed to attain any great commercial success (in spite of the group’s somewhat dubious claim in a contemporous issue of Record Mirror that, at a post-recording séance, a spirit identifying itself as ‘the devil’ communicated the vital prophecy of ‘Felius Andromeda- HIT.’) ‘The Funeral of Us All’, set to be released as the next Felius Andromeda single before the group’s decision to split, found its way onto Second Hand’s 1971 album ‘Death May Be Your Santa Claus.’

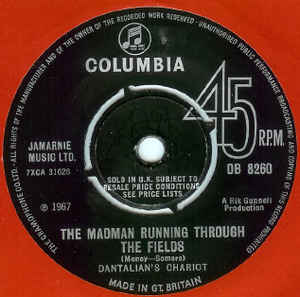

6: ‘Sun Came Bursting Through My Cloud’- Dantalion’s Chariot (A-Side: ‘The Madman Running Through The Fields’)

‘Everyone seems determined to knock Dantalion’s Chariot- including hairy colleague Mick Farren’, John Peel wrote for International Times issue 19 in October 1967. ‘However, I know that Zoot Money is sincere in his sudden reformation and he’s not trying cynical bandwagon jumping as has been ofttimes suggested.’

When Zoot Money’s Big Roll Band suddenly transitioned into Dantalion’s Chariot in the summer of 1967, many within the underground’s inner circle were, not surprisingly, skeptical of the motives behind such a change given the popular psychedelic sentiment in the wake of the Beatles’ Sgt Pepper album. Yet, with their debut live appearance at the Windsor National Blues Festival that August, they impressed not only with their material but also their impressive visuals: donning white kaftans and having painted all of their guitars and equipment white, the ubiquitous liquid lightshows of the day looked particularly impressive bubbling over them.

The sole single cut by Dantalion’s Chariot is now viewed as a classic of the psychedelic genre, although the B-side, Sun Came Bursting Through My Cloud, a delicate, folkish waltz bordering on chamber music, is seldom compiled today. The warm, sunny disposition of this particular composition embodies the Summer of Love just as strongly as the schizoid identity crisis of the A-side. The psychedelic experience and the pursuit of far-out trippiness at any cost has come to colour modern perception of the Summer of Love, overshadowing the tender naivety and noble intent of societal change that lay beyond the acid-tinted gimmickry. Two sides of the same coin, two sides of the same single.

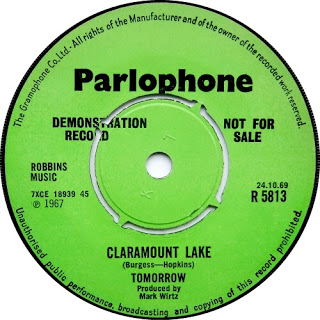

7: ‘Claramount Lake’- Tomorrow (A-Side: ‘My White Bicycle’)

‘Claramount Lake’, a jaggedly jaunty slice of pastoral psych, captures Tomorrow’s live sound better than its more renowned A-side, ‘My White Bicycle.’ Free of the vertigo-inducing stereo studio trickery of the flip, Steve Howe’s (another future member of Yes) oscillating, spiked guitar motifs have more room to breathe, more blank space in which to paint their paisley pictures. As ever within the genre of British psychedelia, the domestic and mundane – in this instance, picnicking in the English countryside and the simple pleasure of doing nothing at all- are redefined with an illusionary tint, twirling playfully into lysergic exoticism. ‘The ducks look red, the swans are green. What a lovely view.’

Despite their sizeable underground reputation cemented by performances at UFO, Middle Earth and the Woburn ‘Festival of the Flower Children’, Tomorrow capsized following the release of their self-titled LP in February 1968. Besides Tomorrow’s small but appropriately rabid modern-day cult following, lead vocalist Keith West is today largely remembered for his simultaneous collaboration with producer Mark Wirtz, ‘A Teenage Opera’, which spawned the #2 hit single ‘Excerpt from a Teenage Opera (Grocer Jack)’ in the summer of 1967. In 1968, drummer John ‘Twink’ Adler cooperated with bandmate John ‘Junior’ Wood under the pseudonym ‘The Aquarian Age’ and recorded the scathing ‘10,000 Words In A Cardboard Box’, supposedly written indirectly about Keith West. Twink also went on to join the Pretty Things and participated in the recording of their classic ‘S.F Sorrow’ album, before forming the prominent Ladbroke Grove group, the Pink Fairies.

8: ‘Sara Crazy Child’- John’s Children (A-Side: ‘Midsummer Night’s Scene’)

Lyrically, here lies the blueprint for Marc Bolan’s hep-cat character studies he would perfect in the early 1970’s as frontman of the electrified T. Rex.

‘Positively the worst group I’d ever seen’, recounted Yardbirds manager Simon Napier-Bell upon witnessing a performance by the pre-Marc Bolan lineup of John’s Children in 1966. John’s Children were amongst the illustrious roster of acts who performed at the 14 Hour Technicolour Dream, and were considered so potentially offensive to the public at large that the Bolan composition ‘Desdemona’ was banned by the BBC- an act of martyrdom that accidentally affirmed their hip, subversive credentials. The group split in 1968, by which point Marc Bolan had already formed the freak-folk iteration of Tyrannosaurus Rex. Their album, provocatively entitled ‘Orgasm’, would not see release until 1970 owing to some particularly strongly-voiced objections courtesy of the Daughters of the American Revolution. ‘Sara Crazy Child’ would remain a fixture of Tyrannosaurus Rex’ early acoustic live sets, where the lyrics pertaining to a ‘seductive bongo beat’ would be backed by the bongos of percussionist Steve Peregrine Took. The faint, otherworldly warbling of Bolan’s voice at the climax of John’s Children’s unhinged, freakbeat rendition of ‘Sara Crazy Child’ was very much an indicator of the shape of things to come.

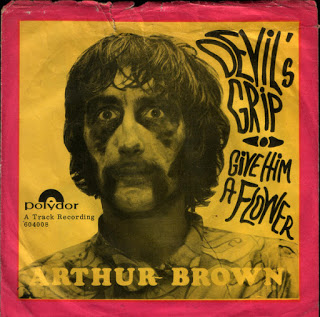

9: ‘Give ‘Em A Flower’- The Crazy World of Arthur Brown (A-Side: ‘Devil’s Grip’)

With tongue firmly in cheek (and, no doubt, flaming colander firmly affixed to his head), the God of Hellfire delivers a social commentary on the state of a scene hounded by police raids (You’re lying in your bath one day and looking at your toes and sixty policemen burst in through the door) and besotted with the fad of flower power (Roses, rhododendrons, lilies, snowdrops!) on the flipside of his debut single.

The winking, self-aware keyboard-led arrangement is almost vaudevillian in tone, even incorporating a brief organ quotation of the popular 1900’s music hall knees-up ‘I Do Like To Be Beside The Seaside’ just before the second verse. The call and response nature of the ending predicts an increasingly violent, visceral edge to Britain’s ‘Beautiful People’, torn between the ideal of responding to any and all provocation by, as Arthur Brown recommends, giving the aggressor a flower, or hitting them on the head ‘with a bicycle chain’ as the cockney inflected response suggests. The apathy-inducing self-indulgencies of the Summer of Love were a source of concern both within and beyond the counterculture; in the words of one underground publication of the era:

‘The atmosphere in London can be almost eerie in its relentless frivolity – Britain seems willing to sink giggling into the sea.’

The Crazy World of Arthur Brown remained a fixture on the airwaves and the live circuit in 1968 as the gentle utopianism of 1967 gave way to disillusionment and protest. The incendiary psych classic ‘Fire’ ascended to #1 and soundtracked the same summer of discontent that served as a muse for both the Rolling Stones’ ‘Street Fightin’ Man’ and the Beatles’ ‘White Album.’

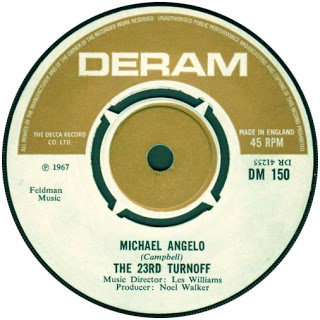

10: ‘Leave Me Here’- The 23rd Turnoff (A-Side: ‘Michelangelo’)

The 23rd Turnoff cut one of the most highly esteemed singles of the era with ‘Michelangelo/Leave Me Here’ in September 1967. Named for the exit off the M-6 that led to their native Liverpool, the 23rd Turnoff, fronted by Jimmy Campbell (described by Bob Stanley as ‘the era’s lost songwriter’) evolved from merseybeat group the Kirkbys, who had gigged extensively at the famous Cavern Club and even supported the Beatles in 1962.

‘Leave Me Here’ follows the blueprint for British psychedelia to the letter, replete with references to Enid Blyton, Oscar Wilde and the Queen, and accompanied by gently lapping waves of sitar. ‘Leave Me Here’ also incorporates an intricately strummed acoustic guitar and a grinningly gone vocal delivery that never sounds more than a few moments away from disintegrating into stoned laughter. Every bit as essential as the oft-lauded A-side, although neither of the tracks on this disc earned much airplay at the time of release (it is believed ‘Michelangelo’ was briefly picked up on by Radio Caroline before being largely forgotten, until it was unearthed again by psych collectors in the 1980s.)

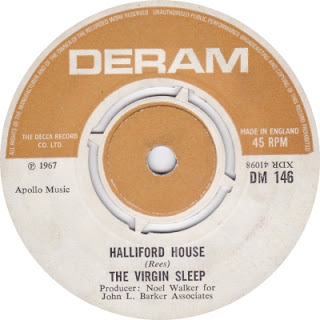

11: ‘Halliford House’- The Virgin Sleep (A-Side: ‘Love’)

Halliford House, where they live in a twilight world…

In common with many of the cult classic psychedelic acts (23rd Turnoff, Tintern Abbey, Felius Andromeda) signed to

Deram- Decca’s ‘progressive pop’ sublabel- over the 1967/68 period, the reputation of West London group the Virgin Sleep (formerly a beat group by the name of ‘Themselves’) hinges entirely on the two classic singles they cut within that period, which flopped before reemerging from the depths following the wave of 1960’s obscurity mining that arose following the unexpected success of Elektra’s ‘Nuggets’ compilation in 1972.

‘Halliford House’ is perhaps the Virgin Sleep’s best number; a creaking cautionary tale in which an L.S.D trip is depicted as a real, tactile place (a theme also enacted upon in ‘Strange House’, a contemporary effort by the Attack). The disquieting, unsettling feel of the melody, punctuated by an admirably restrained guitar solo, brings to mind Lennon’s ‘Cry, Baby Cry’. Meanwhile, the lyrics extol both the virtues and the dangers of the acid experience. Halliford House, seemingly a Victorian-styled schoolhouse, is populated by ‘men and women’ reduced to ‘boys and girls’, hinting at the popular mentality of returning to ones’ childhood that fueled ‘Strawberry Fields’,‘Penny Lane’ and countless other Brit-psych classics. These diverting effects are not as temporary as some would like- ‘some of them will never get out.’ A fitting, pseudo-prophetic statement at the dawn of an era that would come to be defined at least in part by the haunting legacy of the ‘acid casualties.’

‘Now it’s empty, full of decay- Peter Pan has flown away….’

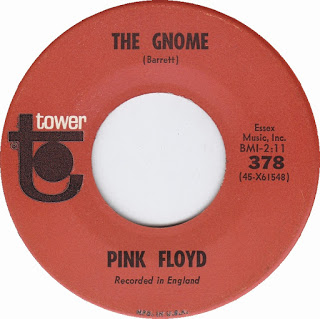

12: ‘The Gnome’- Pink Floyd (A-Side: ‘Flaming’)

Speaking of acid casualties…

The immaculately turned-out Grimble Gromble, the scarlet-tunic wearing gnome who populates this cracked nursery rhyme, serves as a fitting analogue to his dandyish creator. Syd Barrett embodied the foppish flamboyance of British psychedelia, with his frilled shirts, velvet double breasted jackets and gaudy cravats- not to mention his voracious chemical appetite.

Syd’s Pink Floyd require no introduction, integral as they were and remain to the development and popularization of psychedelic music, and no self-respecting list compiling key cuts from this era is truly complete without them. In 1967, they were perceived as living, breathing manifestations of the anarchic spirit of the underground. As Jenny Fabian illustrates;

‘They were opening the doors of musical perception and we felt they belonged to us. There were other people . . . there was Dylan, but he was far away and sort of God-like, The Beatles had evolved, but they didn’t play live. So The Floyd were like our local consciousness come to life. It was as though they’d always been there . . . poets from the cosmos.’

Syd Barrett was ‘a little wild Puck figure coming out of the woods’ in the words of Emily Young- supposedly the muse behind ‘See Emily Play’, a #5 psychedelic hit that summer. ‘He seemed to me to be borne of the English countryside.’ Born of the English countryside he was- Barrett’s bucolic childhood experiences would continue to encroach upon his lyrical content for the duration of his all-too-brief career. ‘The Gnome’, an album track on the crucial ‘Piper at the Gates of Dawn’ LP eventually released as a B-side late in the year, showcases many of Syd Barrett’s guiding songwriting idiosyncrasies. His Tolkien-esque imagery captured the underground fascination with all things Middle Earth, whilst his distinctly English-accented vocals would enormously influence David Bowie- who paid homage to Barrett by covering ‘See Emily Play’ on his 1973 LP ‘Pin Ups’.

13: ‘Listen To The Sky’- The Sands (A-Side: ‘Mrs Gillespie’s Refrigerator’)

‘Listen To The Sky’ is an unlikely anti-war masterpiece. There’s a poignant eye for whimsical detail to be found in this tale of a reluctant pilot in an unnamed war. The responses of the pilot (endearingly named ‘Bertie Baker’) are deeply human; when he receives his conscription notice he is ‘horrified’, when he receives his uniform he wishes he could be with his family, and when he finally takes flight for battle, his eyes ‘full of rain’ are in conflict with his ears ‘full of praise.’ When he ultimately dies amidst a twisted tangle of burning wreckage, the powers-at-be strive to sanitise the horror, forging a letter on his behalf to frame his death as ‘not in vain.’

Thankfully, the military authorities have the foresight to change Berties’ socks so that he ‘looks nice for his folks’ at his funeral. Phew.

On the surface, this is a catchy popsike song in the same vein as the Bee Gees penned A-side. Yet, the lacerating guitar flourishes punctuating the harmonic choruses, the subversive lyrical content and the sensory overload of the denouement (featuring air raid sirens and an invocation of Gustav Holst’s ‘Mars, the Bringer of War’ from the Planets suite) combine to make ‘Listen to the Sky’ one of the all-time finest recordings from the psychedelic era. It’s a scathing protest against the bureaucracy and sanitisation of the horrors of war, in line with popular anti-war sentiment in 1967 as the unignorable sceptre of the Vietnam bloodbath loomed ever larger on both sides of the Atlantic.

14: ‘Colour of My Mind’- The Attack (A-Side: ‘Created by Clive’)

The Attack almost single-handedly define the subcategory of druggish garage rock popularly known as ‘freakbeat’. There is more than a whiff of well-crafted, slick mod-pop to the Attack’s 1967 John du Cann-penned B-side ‘Colour of My Mind’, with a definite sense of urgency that evokes the frenetic shindiggery of a Swinging London now fuelled as much by acid as by amphetamines. The Attack withered on the vine thanks to the neglect of their label, Decca, which shelved several of their recordings- including the classic ‘Magic In The Air’ single and a projected concept album based upon the Roman gods of war- on the basis that they were ‘too heavy’ to be commercially viable. In the aftermath of the Attack, Du Cann would flit restlessly from the studio-only project the Five Day Week Straw People, the Cream-influenced riffing of Andromeda and the progressive rock of Atomic Rooster.

Yet, the reputation of the Attack has only grown with the passing years. As Jon Mills acknowledges, they ‘have a far larger fan base now than they ever did during their existence.’

15: ‘Vacuum Cleaner’- Tintern Abbey (A-Side: ‘Beeside’)

A highly cherished single that often commands prices of up to £1000 in auction.

But does Tintern Abbey’s psychedelic Fabergé egg deserve the hushed reverence bestowed to it by rabid psych collectors? Yes, it rather does.

Sourcing their name from William Wordsworth’s poem ‘Lines written a few miles above Tintern Abbey’ and managed by teenage multi-millionaire Nigel Samuel (who funded plenty of publicity in International Times) Tintern Abbey’s only single was released in December 1967, whereby it was promptly stifled amidst the competitive Christmas market.

The intoxicating ‘Vacuum Cleaner’ has since found its way onto compilations including Nuggets II, Chocolate Soup for Diabetics and The Psychedelic Scene.

Woozy, crushed velvet vocals, blatant drug references, a hazy, distorted guitar solo- ‘Vacuum Cleaner’ is one of the undisputed jewels in British psychedelia’s crown. The consumerism of the mod movement is condemned (‘new clothes can’t buy my soul’) in favour of the introspection and escapism of the psychedelic lobby and the chemical temptations it brought (‘fix me up with your sweet dose’). In the few live shows Tintern Abbey performed, ‘Vacuum Cleaner’ was the group’s opening number. A projected follow-up single and an album (scheduled for release in August 1968) never materialised. No sooner had Tintern Abbey arrived on the scene, they were gone- taking 1967, the epochal year of flower power, with them. In parallel to the psychedelic era they were spawned of, the exotic mystique surrounding Tintern Abbey increases day by day- even as the Summer of Love recedes into ever-distant memory.

‘Come in, ’67, your time is up……’

– Jack Hopkin

Array