1968 Brit-Psych B-Sides

As 1967 drew exhaustedly to a giddy close, it became gradually apparent that the childlike optimism of the Summer of Love had dissipated, never to return. It was time for the flower children to reap what they had innocently sown, and a grim harvest awaited; an odyssey of upheaval on an epic scale, 1968 proved a pernicious casserole of violence, acid-enfeebled oblivion, mass disillusionment and increasingly anarchic rhetoric both within and outside of the counterculture.

The generational gap widened to a gape throughout this polarising twelve-month tumult, pock-marked with the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr and Robert Kennedy in the United States, Enoch Powell’s divisive ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech in the United Kingdom, and the student demonstrations and general strikes in Paris. All the while, television screens retched forth images of a Vietnam pulverised and bleeding beneath skies congested with American bombers, Biafran children reduced to starving, skeletal waifs as the Nigerian Civil War churned atrociously on, and teenaged anti-war protestors at the Chicago Democratic National Convention spontaneously chanting “the whole world is watching” before the stunned media even as they were beaten, maced and arrested by local police. On the other side of the Berlin Wall, Czech reformers in Prague embraced Scott McKenzie’s impassioned ode to hippiedom, ‘San Francisco (Be Sure To Wear Some Flowers In Your Hair)’ as an anthem for their freedom and independence. With virulent symbolism, the military might of the Soviet Union buried their ambitions beneath the rattling tracks of their massed legions of tanks.

Even amidst the gaudy camp of Swinging London, the relentless frivolity could no longer camouflage the palpable feeling that something was very wrong. On March 17th, an anti-war march upon the U.S embassy in Grosvenor Square (fronted by activist Tariq Ali and actress Vanessa Redgrave) was set upon by a throng of policemen on horseback. “I remember being terrified at being chased down by what seemed like scores of mounted police with truncheons flailing about”, witness and participant Robert Newson recounts of this Peterloo-in-miniature,“…while the square was blocked off so that none who found themselves on the inside could get out.” Calmly surveying the pandemonium from nearby was Mick Jagger, Byron reincarnate, the embryonic ‘Sympathy for the Devil’ no doubt sambaing wickedly in and out of his thoughts. Poet Adrian Mitchell discussed his participation in similar protests during a BBC radio interview, in which he commented upon the symbolic use of red paint to evoke the blood spilled in the Vietnamese jungles. The Middle Earth club, the safe haven and de facto headquarters of the resident London hippies after the closure of the UFO, was raided repeatedly by police, its patrons searched, humiliated and vilified. During one of these raids, as the search on the dancers and performers alike went underway, a pianist was heard to play a composition by the name of “The Death March”. If the mood of 1967 was one of dreamy idealism, 1968 certainly didn’t pull any punches in providing a dramatic and confrontational hangover.

“The music industry capitalised enormously on psychedelia”

Flower power couldn’t be more obviously dead. Yet, with the appropriation of hippie fashions and colloquialisms in mainstream media, the garish corpse of the Summer of Love was paraded shamelessly through the streets. Much to the chagrin of the underground, psychedelia had gone mainstream. Advertisements came adorned with groovy Peter Max artwork and consumers were now implored to “turn on!” with a Pepsi or encouraged to collect their free “way out!” psychedelic posters sold with their Campbells tomato soup. The music industry capitalised enormously on psychedelia, and the experimental flair of early lysergic-influenced records was buried beneath a pile of newer, ‘psychedelia by numbers’ groups who slavishly copied all that had been recorded before, pilfering the Sgt Pepper album for every recording trick it had within its iconic sleeve. As Frank Zappa accurately related with discernible venom on the Mothers of Invention’s aptly titled 1968 LP, ‘We’re Only In It For The Money,’ “Every town must have a place where phony hippies meet- psychedelic dungeons popping up on every street….”

“instrumental virtuosity was quickly replacing studio experimentalism”

Charlatans aside, others still were earnest in their attempts to resurrect flower power through sheer force of belief, having been endeared to the movement first-hand the previous year. Like children in a pantomime straining to resurrect the ailing Tinkerbell, their naivety shielded them from the harsh developments that sullied the short cultural road between ‘All You Need Is Love’ and ‘Helter Skelter,’ from beads and kaftans to barricades and whispered talk of revolution. By the end of the year, psychedelia was fading just as quickly as it arrived in 1965-66. With bitter irony, by the time groups that kick-started the movement at the UFO Club the previous year (for example Tomorrow, Soft Machine and the Pretty Things) committed their then-cutting edge live repertoires to record, the moment had passed and the limelight was firmly upon heavier ensembles such as the Gun, Deep Purple and the newly formed Led Zeppelin. Even though such groups were greatly indebted to their psychedelic origins, instrumental virtuosity was quickly replacing studio experimentalism.

The first year in which albums outsold singles, 1968 marked a crossroads in the development of psychedelia into progressive rock. Increasingly, the LP would be the format of choice for underground-centric groups, where, no longer constricted by the time limitations of a 45rpm single, they would be free to indulge their every excessive whim. A further threat to the short-lived praxis of the psychedelic single was the fast-encroaching, multitudinous psych backlash comprising the ‘roots rock’ revival spearheaded by Bob Dylan and the Band, a ‘blues boom’ in the U.K adhered to with fanatical reverence by the likes of Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall and Savoy Brown, and the powerful force of rose-tinted nostalgia for the retrospectively safe and cosy 1950s- even the trailblazing Beatles, unable to resist a brief dive into yesterday, interrupted their recording sessions for the White Album that September so they could watch the network premier of Little Richards’ 1956 rock ‘n roll movie ‘The Girl Can’t Help It’, no doubt an early influence upon the retrophiliac flavour of the ‘Get Back’ sessions of 1969. Nevertheless, even if the hallowed heyday of the psychedelic era was just short of dipping off of its narrow apex, 1968 spawned an array of classic 45s, many of which featured B-sides far more accomplished than much of the ersatz psychedelia quickly bestrewing the singles charts.

The following 15 B-sides are among the best recordings from the long, strange trip that was 1968. Some famed, some all but forgotten. Some borne of the underground, others borne of Denmark Street’s cynical efforts to capture a passing fancy whilst it still had a captive demographic.

Regardless of origin or obscurity, all contribute to the colourful motley mosaic of the mainstream prime (not to mention countercultural decay) of psychedelia. Love songs in celebration of the 1967’s stillborn promise of Elysium, laced with 1968’s potent punch of melancholia, spiritualism, self-destruction and all the studio trickery that the sonic arsenals of Abbey Road, Olympic and their ilk could muster.

To quote Stanley Unwin: “Are you sitting comfy-bold two-square on your botty? Then I’ll begin.”

1: ‘In My Mind’s Eye’- Ramases & Selket (A-Side: ‘Crazy One’)

The first symptom of former army P.T instructor turned central heating salesman Martin Raphael’s radical conversion came in 1966, when he had the Sheffield home he shared with his wife (the 1957 carnival queen of Felixtowe, Dorothy Laflin) renovated to adhere to ancient Roman vogue. Within a couple of months, he went a further step beyond, shaving his head and adopting anachronistic silk robes as unconventional day-to-day attire. Whilst information is scarce- indeed, a sizeable contingent of fans and psych scholars believe Raphael’s true name to have been Barrington Frost- available sources hold a consensus upon what they consider the pivotal moment in the life of this abstruse man: in 1968, he came to believe he was the vessel for the reincarnated Egyptian pharaoh Ramases, supposedly following a visitation-invoked epiphany as he sat in his car. As both an avatar of and an oracle for the Pharoah, the self-renamed Ramases had to disseminate the word and gather as wide a following as possible. This being 1968, the medium he chose by which to do so was- naturally-creakingly evocative, Egyptian- influenced psychedelic pop. Likely assuming Ramases’ persona to be a trippy alter-ego sales gimmick, CBS Records signed him with surprising yet charming period haste. Joining him on his debut single was Dorothy, under the sobriquet of Selket, a tribute to the ancient Egyptian goddess of fertility and nature.

Whilst A-side ‘Crazy One’ would later be reworked into ‘Quaser One’ on Ramases’ cult classic 1971 LP ‘Space Hymns’, (the recording of which saw inceptive involvement by what was soon to become 10 cc) ‘In My Mind’s Eye’ was left behind as a curio of late 1960’s psychedelia that later accrued attention amongst keen-eyed record store vultures thanks to exposure on a number of crucial psych era compilations. At less than three minutes long, ‘In My Mind’s Eye’ is a brief but telling glimpse into the complex mind of its creator. A modern-day riddle of the Sphinx, it groaningly whips up a Cairo sandstorm that brushes upon motifs that Ramases would continue to explore throughout his evanescent career, with prominent lyrical references to distant planets and the “magic Nile.” Regrettably, Ramases took his own life in 1978, a tragedy compounded by the destruction of many of his personal effects and unreleased demos in a fit of jealous anger by Selket’s second husband. Ramases’ increasingly beloved few surviving recordings are his legacy.

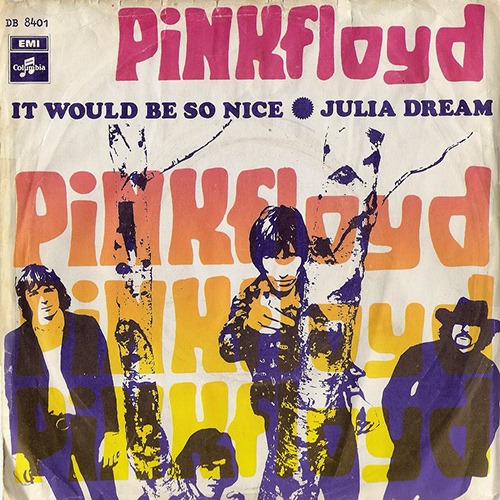

2: ‘Julia Dream’- Pink Floyd (A-Side: ‘It Would Be So Nice’)

One of the foremost poster children for British flower power, Syd Barrett’s petals were ineluctably wilting by early 1968. Much has been written of Barrett’s L.S.D-catalysed mental decline, of the disastrous tours of autumn 1967 in which, when he wasn’t staring mutely beyond audiences and interviewers alike, he was letting Brylcreem and crushed Mandrax leak down his face as though he were a melting candle, slowly detuning his guitar purposefully onstage, or being substituted outright by David O’List of the Nice. Syd Barrett’s name has come to be synonymous with acid burnout, a modern Aesop’s fable in stark warning of the risks of chemical gluttony. In his final effort as Pink Floyd’s primary songwriter, Barrett contributed an unlearnable song by the name of ‘Have You Got It Yet,’ which, in a concluding act of madcap idiosyncrasy, he would intentionally alter as soon as his bandmates managed to master the arrangement. Plainly, Pink Floyd, well established under Barrett’s guidance as Britain’s most popular ‘underground’ attraction, were at a crucial crossroads of blind loyalty to their frontman (himself by now little more than a dark-eyed augury of hallucinogenic overindulgence) versus pragmatic self-preservation of the band. Whilst en route to a performance at Southampton University in January 1968, the group reluctantly chose the latter and elected not to pick Barrett up. He was purged from the very ensemble he had formed three years prior, and Pink Floyd continued on as a reconstituted four piece (having recruited guitarist David Gilmour shortly before Barrett’s untimely departure).

‘It Would Be So Nice’, the first single Pink Floyd cut in the aftermath of Barrett’s ousting, paints a crystal-clear picture of a rudderless group hoping for a hit single in the vein of ‘Arnold Layne’ or ‘See Emily Play’. Its’ whimsical weightlessness lacked the old Barrett-Midas touch and has been described by John Harris as “akin to the music of such faux-counter culturalists as the Hollies and the Monkees.” Roger Waters-penned B-side ‘Julia Dream’, however, points to the plaintive, melancholic psychedelic folk that would later characterise live classics such as ‘Green Is The Colour’, ‘Cymbaline’ and ‘Fat Old Sun.’ Drenched in languidly elegiac mellotron and featuring vocals delivered with delicate thistledown deference courtesy of newcomer David Gilmour, ‘Julia Dream’ has a foot in the band’s psychedelic past and the other firmly planted in the spacey ambient exploration that would define Pink Floyd’s output for the remainder of the decade, beginning with 1968’s ‘A Saucerful of Secrets’ LP.

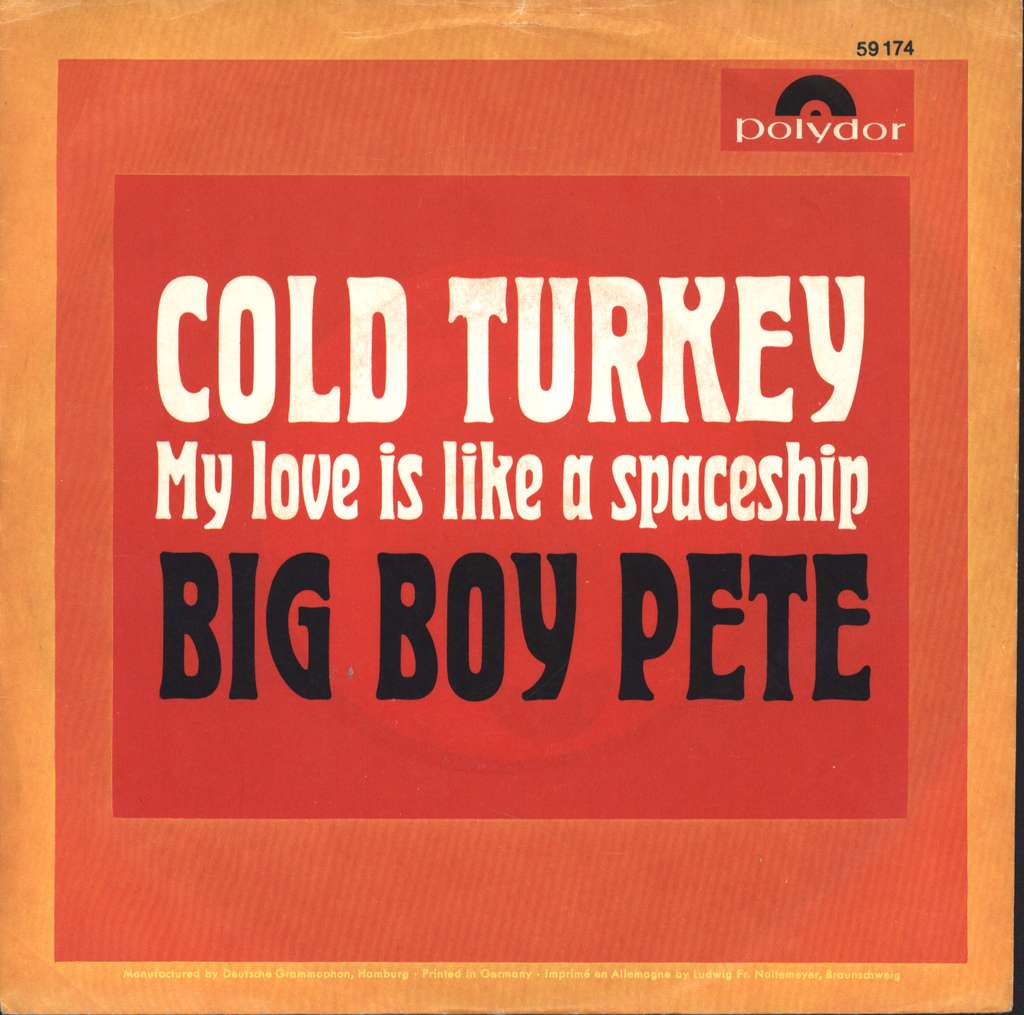

3: ‘My Love Is Like A Spaceship’- Big Boy Pete (A-Side: ‘Cold Turkey’)

Peter Miller, more widely referred to by his alias, ‘Big Boy Pete’, was already a veteran of the music industry by the time he waded into the age of ‘psychobollox’ (as he affectionately refers to the period between 1966 and 1969, when he completed “literally hundreds” of recordings in a studio decked out with “lava lamps and Hindu visuals”). Prior to his psychedelic years, Miller enjoyed a colourful career on the brink of stardom, brushing shoulders with some of the brightest and best musicians of the age. As a session player, Miller provided lead guitar for Marty Wilde’s 1961 single ‘Ever Since You Said Goodbye.’ During his tenure as a guitarist for Peter Jay and the Jaywalkers, he played support gigs for the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Cream, the Animals, and a slew of other iconic names. When he went solo in 1965 to cut his surprisingly heavy Troggs-soundalike freakbeat single, ‘Baby I Got News For You’, Miller was accompanied on record by the fresh-faced Peter Frampton and members of what was soon to become the Herd.

The biting mod-psych of ‘Cold Turkey’, Big Boy Pete’s 1968 single (predating John Lennon’s solo 45 of the same name by a year and a half), is highly venerated in collector’s circles. What concerns us, however, is the highly unusual B-side. ‘My Love Is Like A Spaceship,’ is, in its’ soaring staccato of vertigo inducing electronic sounds, surely one of the stranger recordings of the era. Big Boy Pete’s studio treated vocals sound akin to what might transpire if Bowie’s Laughing Gnome were to find the medicine cabinet, nitrogen pitched and peppered as they are with seemingly improvised giggles. At one point a patience gnawing repetition of the word ‘beep’ is timed to mirror the relentlessly grinding march of fuzz guitar. It’s a bizarre, far from commercial record, but it was certainly in step with the undercurrent of campy space race fixation that ran throughout 1968- indeed, this was the year of Stanley Kubrick’s science fiction epic ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’; furthermore, ‘Star Trek’ continued to exert a powerful hold on popular imagination, a fascination only fuelled in December 1968 by the very real exploits of the lunar- orbiting Apollo 8.

4: ‘Tales of Flossie Fillett’- Turquoise (A-Side: ’53 Summer Street’)

Come 1968, Decca and ‘progressive’ sub label Deram were straining to support the vast roster of acts they reflexively signed in the years following their failure to sign the Beatles. Without adequate promotion or publicity, countless perfectly worthy psychedelic pop groups succumbed to the quicksand of anonymity, taking their unreleased acetates with them. Enter Turquoise, a group formerly known as the Brood whose demo recordings earned them endorsement from Dave Davies and John Entwhistle. Nonetheless, they didn’t attain a fraction of the airplay they were due.

Of the two singles Turquoise did manage to release in 1968, ‘Tales of Flossie Fillett’ comprised the B-side of the first. With their acoustic guitar driven character study of the eponymous Flossie and her picture-book playmates, Turquoise reside firmly on the same droll village green as their real-life neighbours, fellow Muswell Hillbillies the Kinks. There’s a hint of futility buried within this outwardly simple nursery narrative, for instance the nihilistic reflection that Flossie will inevitably be “forgotten” only to be replaced by “another Flossie with a different face” and the payoff that- dig this- “the tales of Flossie Fillett all happened in a day.” Given the strong Kinks influence in ‘Tales of Flossie Fillett’, it comes as no surprise to note that Turquoise were close friends with the Davies brothers, even recording an (at the time unreleased) cover of ‘Mindless Child of Motherhood’ in 1969 after being supplied with a demo by Dave Davies. The denouement of ‘Flossie Fillett’ seemingly includes a shout-out to Turquoise’s famous friends in the Who with a reference to “Moon the Loon” (the nickname of the wayward Keith Moon, no less) and, perhaps more tenuously, a possible reference to the Kinks’ 1966 album ‘Face to Face’ (“All effects are face to face, who did it we don’t know how.”) Turquoise’s follow-up A-side release, ‘Woodstock’, has the unorthodox accolade of memorialising the iconic music festival of the same name nine months before it even happened. Its’ repeated ending refrain of “Would you like to go back to Woodstock” is but a happy coincidence, since the group were in actuality singing about Woodstock, Oxfordshire.

Needless to say, the projected feature film starring Turquoise (ill-advisedly announced by Decca in 1968), tentatively titled ‘If That Was A Hard Day’s Night, What Do You Think This Is?’, never saw the light of day.

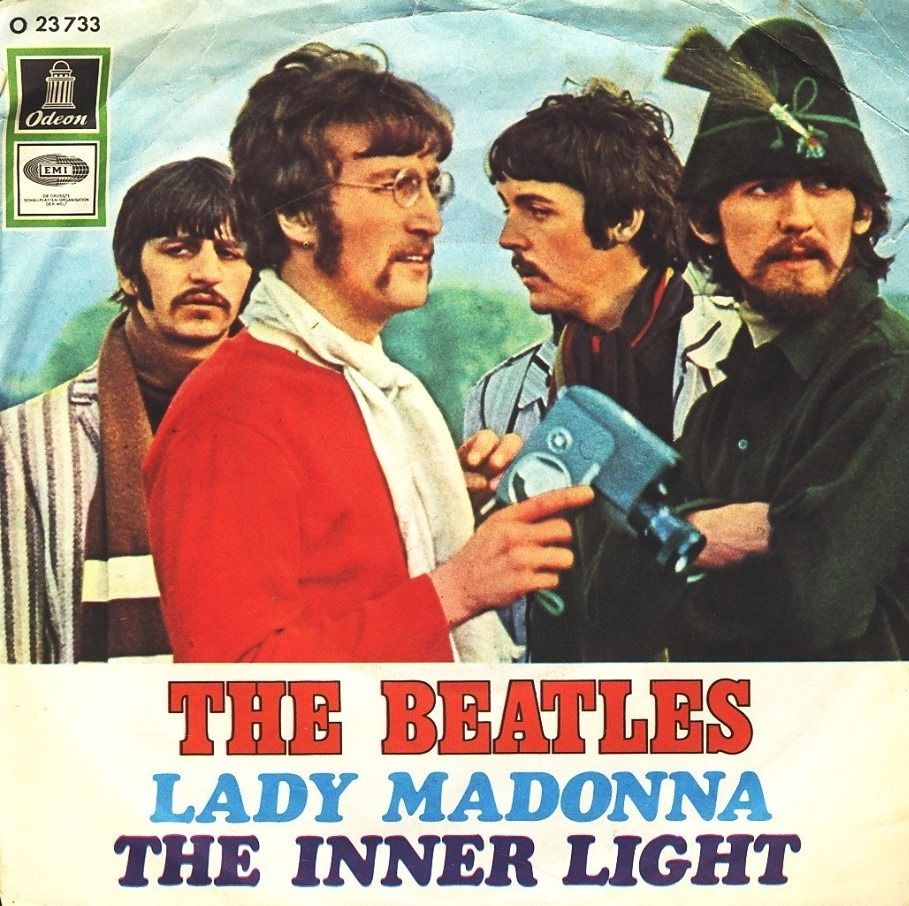

5: ‘The Inner Light’- The Beatles (A-Side: ‘Lady Madonna’)

Paul McCartney’s ‘Lady Madonna’ was the first record released by the Beatles in 1968, an affectionate pastiche of Fats Domino’s 1956 hit ‘Blue Monday’ both thematically and in sung execution. With its raucous piano riff and conspicuous lack of lysergic influence, it was an early warning shot of the rock ‘n roll revival about to wipe the slate clear of tie-dyed psychedelic headiness. As if to emphasise this point, an advert for the then-new single describes the Beatles humorously as “a new rock and roll combo direct from Hamburg.”A number one hit, it served to tide Beatles fans over whilst the group absconded to an ashram at Rishikesh, India to continue their study of transcendental meditation under the tutelage of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi. Much of the White Album would be composed over the course of this contemplative quarantine.

Alongside an alumnus of similarly cosmic-minded seekers that included beatnik-turned-hippie troubadour Donovan, Mike Love of the Beach Boys and actress Mia Farrow of ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ fame, the Beatles- particularly George Harrison- thrust the intoxicating allure of Indian culture even further into the Western popular consciousness, publicly eschewing the use of L.S.D in favour of mysticism and meditation. The orientalism of the psychedelic era may have been yet another fad to follow for a number of the pop groups of the time- indeed, the formerly exotic sounds of the sitar, oud, tambura and other Asian instruments could be heard liberally scattered throughout the charts thanks to hit psych singles by Traffic, (‘Paper Sun’, ‘Hole In My Shoe’) the Lemon Pipers (‘Green Tambourine’) and the Cowsills (‘The Rain, The Park and Other Things’)- but for pioneer George Harrison it was the beginning of a lifetime of earnest fascination and spiritual devotion to Hinduism. Indian instrumentation was no novelty musical prop for George, even if the enormous influence of his own recordings inevitably saw it utilised as such by his compeers. Harrison’s respect for classical form is particularly evident in ‘The Inner Light’, his final and most authentic foray into Indian raga, which marked the first time one of his compositions was released on a Beatles single. Whilst not a ‘psychedelic’ recording per se, it nonetheless bears inclusion for pertaining to the culture that made unlikely and reluctant popstars of classically trained musicians such as Ravi Shankar and Ustad Vilayat Khan, among others.

Recorded in Bombay In January during recording sessions for the ‘Wonderwall’ soundtrack, ‘The Inner Light’ features Indian session musicians playing in a style closer to Carnatic temple music than the Hindustani, sitar-and-tabla approach exhibited in ‘Love You To’ and ‘Within You Without You.’As such, it is more melodic but no less rich in attention to cultural detail than Harrison’s previous Indian efforts. The message of the song (with lyrics adapted from chapter 47 of the Tao Te Ching, recommended to George by Sanskrit scholar Juan Mascaró) is simple: all the answers to the human experience can be found, uncomplicated, within oneself. In other words, rather than clouding and cluttering their perceptions with doubts and unnecessary philosophising, Harrison implores his listeners to embrace simplicity. He would return to this theme of ‘arriving without travelling’ in Yellow Submarine’s ‘It’s All Too Much’, in which he sings “the more I learn, the less I know.”

6: ‘Morning Sunshine’- The Idle Race (A-Side: ‘The End Of The Road’)

The Idle Race released their debut LP, a toytown-tinged quasi-concept album by the name of ‘The Birthday Party’, in October of 1968. A lavish gatefold sleeve revealed when opened a photo collage depicting the titular birthday party, the guests politely sitting row by row in their dinner jackets and bow ties. Included are old heroes like Buddy Holly and Little Richard, DJs Keith Skues, John Peel and the Emperor Rosko, comic actor Oliver Hardy, ‘an elderly fan’, Rolling Stone Brian Jones and all four Beatles. Perched between DJs Jimmy Young and Tony Blackburn is a little boy, soaking in all of the disparate influences of his esteemed company. The accompanying numbered key identifies him as ‘Jeff Lynne, Idle Race, Aged 8.’

Emerging from the same Birmingham punch bowl that spawned the Move and the Moody Blues, the Idle Race were respected by critics and peers alike. However, they never quite attained the level of visibility they deserved for their eclectic output, mutating between vigorous modish freakbeat and ornate psychedelic pop confections with music hall leanings. Jeff Lynne, only 20 in ‘68, was already establishing the foundations of the symphonic Beatlesesque sound that would later become his trademark and elevate him to household name status with the Electric Light Orchestra project in the 1970s. 6 of the 13 tracks included on the contemperously neglected Idle Race debut were unleashed as singles in the months prior to the LP’s release, including ‘Morning Sunshine’, paired with album closer ‘The End Of The Road’ in May 1968. Described by Bruce Eder as “one of the prettiest songs to come out of the entire Birmingham scene”, ‘Morning Sunshine’ is a harmony-laden, dewy-eyed slice of psych optimism spiked with a shot of longing sorrowà la the Zombies’ ‘Care of Cell 44’. An exercise in well-crafted concision, it packs a lot into its 1 minute, 48 seconds runtime, with serenading interludes of gossamer mellotron and distantly sanguine Pet Sounds guitar licks suspended distantly throughout.

7: ‘Dandelion Seeds’- July (A-Side: ‘My Clown’)

‘Dandelion Seeds’, B-side to the brooding acid drone of ‘My Clown’, is a bonafide classic of unhinged British psychedelia. Emerging shaky and uncertain, a floridly funky guitar riff manifests marshy from the silence, pirouetting jocularly for a period before collecting itself and sprinting into a rhinoceros charge straight in the direction of the listener. About a minute and a half in, just as it seems the wheels are about to fall off, the incendiary barrage of dueling guitars dims momentarily.Amidst this serene oasis, the stabbing strumming can still be heard murkily on the horizon, as though playing above a body of water we’ve sunk unknowingly beneath. Some omniscient figure intones “I tell the time for you/Twelve o’clock or noon” through dense reverb. Then it’s back into to the thick of that effervescing riffing and a continuation of the sickly-sweet lyrical imploration to join the singer, high as a kite “up above the trees.” ‘Dandelion Seeds’ closes as it opens, the soundscape twitching and sloping, disjointed and spent, back into the primordial swamp.

Not bad for a track just over three minutes long and for a group billed by Spencer Davis as the ‘Eastern Hollies,’ a comparison that does Ealing’s mighty July little justice. A full album followed in July 1968 (when else?) courtesy of Major Minor, the demented sleeve art -complete with a bizarre heterochromatic bovine beast and a frog with human teeth- perfectly capturing the spirit of the strange music within. Despite including first-rate Barrett-esqueditties such as ‘Hallo To Me’, ‘Jolly Mary’ and ‘Crying Is For Writers’, it was too odd an LP for mainstream consumption (one reviewer dismissed it as “the worst album they’d ever heard and a complete waste of plastic”) and July ended prematurely in 1969. Vocalist Tom Newman would nonetheless make it to the bank yet; helping Richard Branson build the Manor Studio, he would go on to produce Mike Oldfield’s smash hit 1973 debut ‘Tubular Bells.’

8: ‘Aeroplane’- Jethro Toe (A-Side: ‘Sunshine Day’)

Whatever did happen to ‘Jethro Toe’? It’s almost as if some loveably ham-fisted intern at MGM misspelt Jethro Tull- or, if frontman Ian Anderson is correct, a loophole was exploited to prevent from having to pay the group their royalties for their debut single. Thankfully for the band named after the inventor of the seed drill, ‘Sunshine Day’/’Aeroplane’ sold pitifully few copies at the time and as such they were not bilked of any great harvest of riches. The discrepancy in name is unintentionally apt, however, as the contents of this 45 bear little stylistic resemblance to Tull’s later output. No lunatic flutes, no jagged Beefheart blues, just lazily hazy swinging hippie pop. ‘Aeroplane’, a composition previously performed by band member John Evan’s blue-eyed soul group from 1964, is reworked here into a lethargic heat haze of harmonic early prog. There’s even a harpsichord solo incorporated just in case you forgot that this was recorded in post-Pepper London.

On June 29th, Jethro Tull joined Roy Harper, Tyrannosaurus Rex and Pink Floyd for the first of a dozen free concerts held in Hyde Park between 1968 and 1971. For a brief midsummer dream in the eye of the storm that was ‘68, the very best attributes of the previous years’ aureate summer were resurrected. The waves of the Serpentine lapped gently against boats rented out by visiting flower children, bells strung on beaded necklaces tinkled past vendors selling International Times and the pungent aroma of marijuana smoke lingered mischievous on the air. Pink Floyd performed an accomplished and mellow selection that combined old material such as ‘Interstellar Overdrive’ with fresher cuts like ‘Let There Be More Light’, in doing so assuring their apprehensive fanbase that the ship was far from sinking. Jethro Tull,“preceded to the park by rumours of their goodness” in the words of John Peel, “played with fire and brought out the first rays of the sun” with a well-received set that included the subtle shimmer of ‘Aeroplane.’ And the rest, as they say, was history.

As for that misnomer on the original MGM single? It is today a key contributing factor to its collectability of the original pressing, regularly valued at hundreds of pounds in auction.

9: ‘Pictures in The Sky’- Orange Seaweed (A-Side: ‘Stay Awhile’)

Orange Seaweed, hailing from Hastings, released their only single in April 1968 before vanishing into the ether when it failed to make a dent in the charts. It is fair to assume that the A-side ‘Stay Awhile’ received some airplay, being a reasonably commercial popsike ballad augmented with brass and some occasional injections of scorching, if slightly out of place lead guitar. The B-side, however, is one of those vaulted ‘where did that come from’ slabs of psychedelic ambergris cherished on the dual bases of quality and rarity in equal measure. There’s a reason that both Volume 7 of the indispensable Rubble collections and the 1968 edition of Cherry Red’s British psychedelia series are named after ‘Pictures in the Sky.’

This is an update to, if not exactly a far-cry from to the untrained ear, the euphoric ‘Lucy in the Sky’ style psychedelia of 1967. There is an alien foreboding evoked by the slithering purr of reptilian guitar that bookends the song and pre-empts each verse. The vocals, delivered by Ray Neale, are matter of fact and sober even as he sings of such absurdities as a prince carrying a message to the sun, whilst bubbling pockets of bass aggressively punctuate the difficult to decipher narrative. When the backing falls away for the chorus, leaving only unaccompanied parochial vocals underscored pointedly with ringing jabs of piano, it’s as if the listener has stumbled unknowingly into some bizarre ritual or sermon. Tapering off into a catatonic stupor of slowly expanding, unearthly tones, stunned repetition of the title and that caterwauling, borderline subliminal monotone siren riff, ‘Pictures in the Sky’ is a wigged-out fever dream from start to finish, very much deserving of its belated lease of eminence.

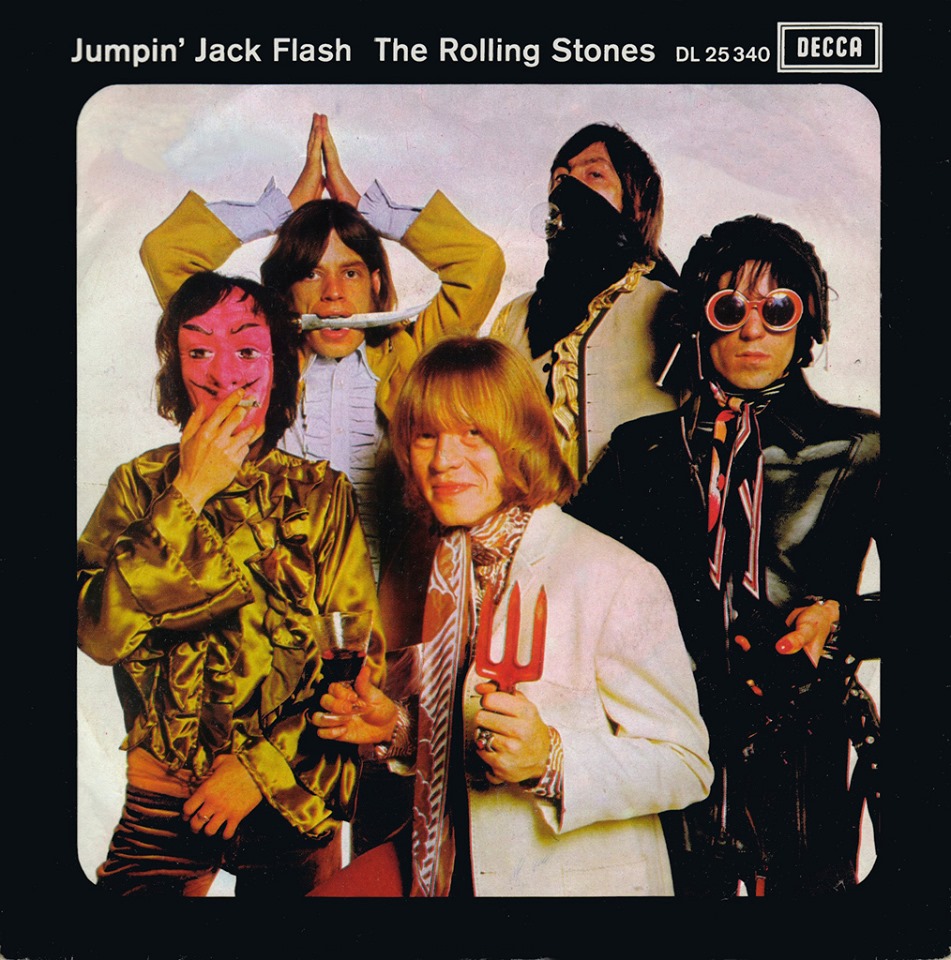

10: ‘Child of the Moon’- The Rolling Stones (A-Side: ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’)

The Rolling Stones drew a short straw in 1967. Despite their prominent role in the development of the genre of psychedelia- see the sitar on ‘Paint it Black’ and the ornate faux-Elizabethan chamber music of ‘Lady Jane’- the Stones spent little time cavorting in the flowers they planted but plenty of time in court after a sensationalist bust at Keith Richards’ Redmond abode saw them propelled into the midst of a high-profile drug trial. The Stones came to be regarded as the sacrificial lambs of the Summer of Love alongside John ‘Hoppy’ Hopkins, and even the typically conservative William Rees-Mogg of The Time spenned a feature rife with vociferous indignation at the unfair charges levelled at them. Entitled ‘Who Breaks A Butterfly Upon A Wheel?’, the piece argued that Mick Jagger and his long-haired chums were facing harsher sentencing than “any purely anonymous man”, a stance that gained surprising precedence within even the politest echelons of British society. By the end of the year Keith Richards’ conviction was overturned, Mick Jagger was conditionally discharged, and Brian Jones was fined £1000. Support for the Stones was short-lived, however, as when they belatedly released the variegated fruits of their oft-interrupted labours in the form of the ‘Their Satanic Majesties Request’ LP it was critically savaged and labelled as derivative- yet another unfair charge, since recording sessions for the album predated much of what they were purported to have copied.

‘Child of the Moon’ occupies an unusual place in the Rolling Stones’ discography, a comparative obscurity that nonetheless made its way into many homes as the B-side to the leviathan smash hit ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’. ‘Child of the Moon’s’ stoned buzz must have seemed anomalous to fans in 1968 when compared to the raw and rootsy energy of the flip side. A muzzy melody penned for Jagger’s muse Marianne Faithfull, delivered in a mesmeric, sedated drawl and with more than a passing similarity to the Beatles’ ‘Rain’, ‘Child of the Moon’ catches the Stones in more sentimental disposition than their ‘bad boy’ image tended to portray. Keith Richards’ nettle sting guitar barbs, the sonorous hum of Brian Jones’ underscoring saxophone part and Charlie Watts’ expert drum rattle combine seamlessly in what must rank amongst the top tier of the group’s exploratory mid-60s recording run. ‘Child of the Moon’ is very much a product of the Stones’ carefully cultivated moody period mystique, the accompanying promotional video positively oozing with the pseudo-philosophical spirit of the era. It portrays the group as timeless gatekeepers of what can be interpreted as a forested counterpart to the mythical River Styx, barring an earthen footpath to the Underworld first from a grinning child and then from an overawed young woman. When a strikingly familiar old lady hobbles into view, it becomes apparent that the never-aging Stones have born witness to every stage of her lengthy life, albeit condensed into the span of just over three minutes. Barely paying her any heed, they permit her to pass them by and continue along to where “the sun glows at the end of the highway”. They silently resume their watch, their period hippie fashions incongruous with their imposing stillness. We catch a final glimpse of the woman, frozen in time as her younger self, stumbling into the darkness as the song concludes. Just as Haight Ashbury heads declared a theatrical mock funeral for their denizen hippie movement in October of 1967, the Stones have emphatically witnessed the first optimistic stirrings, the uncertain yet beautiful heyday and the ineludable expiration of the flower children.

‘Child of the Moon’ was the Rolling Stones’ final foray into psychedelia. They would never again return to such chimeric shores.

11: ‘Dr Jekyll & Mr Hyde’- The Who (A-Side: ‘Call Me Lightning’)

Keith Moon’s unconventional and locomotive-paced drum din was an integral feature of the Who’s characteristic live cacophony, but much of his legacy of lunacy was forged by his offstage antics. Far from just any old percussionist, the fun-loving, drum kit-kicking, toilet-exploding, hard-boozing Moon was every bit the embodiment and living essence of the infamous ‘Oo, his unique brand of self-destructive bedlam always delivered with a wink and a smile. His notorious 21st birthday party in Flint, Michigan resulted in a fine worth $24,000 to cover damages inflicted upon a ransacked Holiday Inn that had the dubious distinction of serving as the shindig’s venue. So absolute was the mayhem on display there that armed police were dispatched to put an end to the psychotic soirée, and Moon awoke groggily in a cell with a missing front tooth.“When you’ve got money and you do the kind of things I get up to,” Keith told NME in the early 1970s, “people laugh and say that you’re eccentric, which is a polite way of saying you’re fucking mad. Well, maybe I am. But I live my life, and I live out all of my fantasies, thereby getting them all out of my system.” Yet, there was only so far that a man could live out a permanent Gustav Metzger daydream and Moon’s liver-cringing alcohol abuse began to take a toll, his conduct becoming increasingly volatile. Paying off his various reparations to atone for a trail of exploded hotel rooms coupled with his already reckless spending meant that Moon often teetered on the brink of bankruptcy, with the Who consistently in debt for much of the 1960s. Even in 1975, with the celebrity of the Who long well established, Moon’s profit from that years’ UK tour had been reduced to a mere £47.35 by the time his outstanding payments were withdrawn. In short, Keith Moon was the Dr Jekyll of the British rock scene.

Or so partner in crime John Entwistle (who admits that “a lot of times when Keith was blowing up toilets, I was standing behind him with the matches”) surmised. The gothic, heavy-heeled ‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde’ was penned by Entwistle and has been described by John Atkins as a “macabre tribute to Keith Moon.” The point of view perspective of the lyrics places us directly in the shoes of Moon the Loon, who growlingly grumbles that “Someone is spending my money for me/the money I earn I never see.” When Moon drinks his “potion” his “character changes” from “the loveable fellow who’ll buy you a drink” into Mr Hyde, the boorish hooligan increasingly becoming the dominant side of Moon’s split personality. Biographer Tony Fletcher recounts an incident in New York in 1968 in which, at a dinner held by agent Frank Barsalona and his wife June, Moon underwent his frightening transition and became so incandescent with drunken fury that he had to be “shaken to his senses”. When Moon sheepishly apologised and departed to his hotel room, Entwistle turned immediately to Barsalona and remarked, “You know my song, ‘Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde?’ Now you see what my inspiration was. This is the first time you’ve seen it, but we see it all the time.”

12: ‘Sycamore Syd’- Focal Point (A-Side: ‘Love You Forever’)

“I could get you a recording contract just like that,” Paul McCartney said, snapping his fingers. “But why should I?”

It was May 1967 in Hyde Park,and fellow Liverpudlians Dave Rhodes and Paul Tennant had given chase when they saw McCartney’s Mini Cooper driving clear from his St John’s Wood home. “Because we are good, our songs are good”, Rhodes replied, apparently justification enough for what was to come next. Paul provided him the phone number of Terry Doran, the manager of the fledgling Apple Publishing Ltd, and the pair came to be the first songwriters to be offered a contract to it. John Lennon was suitably impressed by their songs, they made rendezvouses with Swinging London royalty such Graham Nash, Vidal Sassoon and Jenny Boyd, and they were to be managed by Brian Epstein- who suggested the duo recruit members for a full band which would be called Focal Point. When Brian Epstein died and their schmaltzy debut ‘Love You Forever’ (released on Deram) bombed, Focal Point were disheartened by the anticlimax and they split in 1969. Focal Point’s great unfulfilled potential is laid bare on B-side ‘Sycamore Syd’, a fuzz freakout of chiming organ, driving hard-psych riffing and pealing piano that has come to be known as the groups’ defining recorded moment.

Sycamore Syd, the grey-bearded man who “sees things as they ought to be”, apparently had a busy succession of years in the late 1960’s.1968 was the “Year of the Guru” according to Eric Burdon and the Animal’s song of the same name on their ‘Every One of Us’ LP. Even though Focal Point’s ‘Syd’ character was based upon John Mayall, the trope of the enlightened, penniless old mystic was omnipresent; the stranger with eyes filled with “love and pain” and the “wise one who loved all the haters” in the Small Faces’ ‘Green Circles’ (1967) and ‘Mad John’ (1968), respectively, not to mention the “hurdy gurdy man… singing songs of love” in Donovan’s ‘Hurdy Gurdy Man’ (1968). Even MAD Magazine lampooned the cross-legged, meditative sage with the cover of their September 1968 issue, featuring an obvious Maharishi parody held stately above the heads of caricatures of the Beatles and Mia Farrow. Meditation, L.S.D-soaked introspection and semi-religious philosophy had seldom been more mainstream and certainly never so intensely capitalised upon, a sore point for advocates of the anti-materialist, drop-out lifestyle. Eric Clapton’s otherwise nonsensical lyrics for Cream’s 1968 hit ‘Anyone for Tennis’ hit the nail on the head with one boldly cynical couplet: “And the Bentley-driving guru/Is putting up his price….”

13: ‘The Otherside’- The Apple (A-Side: ‘Doctor Rock’)

It takes little imagination to deduce the inspiration behind the name of Cardiff group, the Apple- one music journalist in particular back in 1969 was likely on the money when he queried on paper, “is it a gimmick to cash in on the name of that well-known organisation in Saville Row?”Appellations aside, the Apple were responsible for two of the most outstanding cuts of the British psychedelic oeuvre, ‘Buffalo Billycan’ and ‘The Otherside.’ With catastrophically poor judgement, Page One Records frittered the strong hit potential of both songs and cast both to the undeserved status of B-side. It wasn’t until both recordings featured on the vastly influential ‘Chocolate Soup for Diabetics’ series of compilations that the Apple earned a wider fanbase.

Those who purchased the ironically poppy and admittedly rather sappy ‘Doctor Rock’ when it was released in December of 1968 likely concluded the title of ‘The Otherside’ to be a standard pun on the concept of turning a 45 over to hear the flip, just as Tintern Abbey had done with their A-side ‘Beeside’, Norman Conquest with ‘Upside Down’ or Cat’s Eyes with ‘Turn Around.’ What they instead received was Jeff Harrad’s pensively lovelorn opus, stately in its fanfare of soaring guitars and fatalist with its’resigned illustrations of a romantic liaison that “has failed to stand the test of time”. Given the composition’s psychedelic stylings, its fair to assume that the arcane ‘Otherside’ the singer tells of is indicative of the reverie afforded by an acid trip- a bountifully available means of escapism in the context of 1968’s “world of mixed up minds.” An album followed in early 1969, produced by Caleb Quaye of ‘Baby Your Phrasing Is Bad’ cult renown who would later go on to work with Elton John. Labouring in vain to attain a grip on the lower rungs of the charts, it didn’t manage to attain an audience despite including a cover of the Yardbirds’ ‘Psycho Daisies’, the viscous kicks of ‘Buffalo Billycan’ and the magisterial downer splendour of ‘The Otherside”. Mixed up minds, indeed.

14: ‘Loving Sacred Loving’- The End (A-Side: ‘Shades of Orange’)

By the time the End released ‘Loving Sacred Loving’ as B-side to ‘Shades of Orange’ in their native U.K in March 1968, they were already minor celebrities- albeit not in the manner they may have initially imagined when Rolling Stone Bill Wyman first took them under his wingback in 1965. In the words of a bemused British article from the era, “The End are brushing up their Spanish. A few months ago, some of their privately-made tapes were borrowed by the rep of a Spanish disc firm. Next thing the boys knew- they were No. 5 in the Spanish charts.” The aforementioned hit, ‘Why’, took the airwaves in Spain by storm in April 1967, and was capitalised upon by the group through television appearances and a series of live performances there. In 1969, they made a sizeable cameo walking down a street in the Spanish surrealist underground movie ‘Al Escondite Ingle‘s’, their song ‘Cardboard Watch’ featuring prominently in the soundtrack. This was clearly a sizeable market, illustrated succinctly when guitarist Collin Giffin spoke of having to teach his bandmates the “lingo- if only to help deal with the flood of letters from Spanish fans.” Not surprisingly, the End’s Spanish fans became their priority, and ‘Loving, Sacred Loving’ saw a limited release there as the A-side to ‘We’ve Got It Made’ several months before it had a U.K release.Writing credits were attributed to Bill Wyman and Peter Gosling.

‘Loving Sacred Loving’, a drifting Carnabetian kite roped to the harpsichord of famed session player Nicky Hopkins and featuring Charlie Watts on tabla, bears so much stylistic similarity to ‘Satanic Majesties’ cuts like ‘In Another Land’ that over the years it has featured erroneously on several Rolling Stones bootlegs. ‘Introspection’, the End’s classic album that included ‘Loving Sacred Loving’, has been glowingly reviewed by Shindig’s Jon Mills as “a masterful mixture of swirling, dream-like numbers, and flowery, but never twee, pop.” It was belatedly released in December of 1969 with the same managerial misjudgement and rotten luck that permeated all too many psychedelic releases of similar high quality. It arrived far too late to catch the long-since receded wave of mainstream psychedelia and by the time it hit the shelves the End had already come to a, well, an end.

15: ‘Let’s Loot the Supermarket’- The Deviants (A-Side: ‘You’ve Got To Hold On’)

A slice of proto-punk anarchy courtesy of underground ringleader Mick Farren and his merry band of pilled-up Deviants, ‘Let’s Loot the Supermarket’ captures the mood of the counterculture’s diehard old guard as they retreated back to the solace of the scuzzy slums of the Notting Hill Gate from whence they had emerged back in ’66. A shambolic singalong, slobbering and slurring to and fro, ‘Let’s Loot the Supermarket’ is hardly ‘psychedelic’ but is a tome to the days when the Ladbroke Grove was the Haight Ashbury of sorts for Britain’s freak scene. Counterculture was no fey weekend hobby for these would-be revolutionaries; “It’s like Germaine Greer said about the underground,” Mick Farren explained retrospectively in 2006, “it’s not some sort scruffy club you can join, you’re in or you’re out. It’s like being a criminal.” The freaks of Ladbroke Grove would only grow more confrontationally mutinous, their hair longer, their drugs stronger and their music ever heavier. Recorded in the midst of a heavy speed binge, reviewer Mark Deming writes that ‘Supermarket’ “…appears to have been recorded by people who lack the ambition to put on their shoes, let alone liberate needed supplies.” Nonetheless, come 1977 the Deviant’s intoxicated ode to shoplifting was once again relevant enough that Mick Farren revisited it for the sake of his new punk disciples.

The hirsute miscreants of the Ladbroke Grove community kept the spirit of psychedelia alive into the early 1970s with their devotion to non-profit, locally based acts such as Quintessence, the Pink Fairies, Hawkwind and the Edgar Broughton Band. They also flocked to support the lumbering caravan of underground,heavy psych and prog-rock brontosauruses- the eardrum-splitting Stray, the punkish stomp of Third World War and the occultist Black Widow- striding in deafening parade through venues such as the Roundhouse and the Marquee.

Psychedelia’s second wind, however, was far from restricted to the delinquency of the Grove enclave. The gentler souls of the ex-flower power movement, uninterested in rioting, looting and hard drugs, joined an exodus out from the no longer swinging capital and into the unspoiled idyll of the English countryside. Like a diaspora of dandelion seeds, they blossomed in unlikely places and before long even that old bastion of tradition, folk music, was laden with psychedelic influence.

Following in the footsteps of the likes of Fairport Convention and the Incredible String Band, the acid-revitalised folk renaissance was shouldered by dozens, perhaps even hundreds of hippies who, over the course of 1969, formed groups with names like the Trees, Spirogyra and the Amazing Blondel.

But, the story of ‘69- the year in which psychedelia’s first wave fired off its’ final parting shots, before the movement regrouped in readiness to weather out the start of anew decade- is one for another day.

– Jack Hopkin

An utterly fantastic article. SO much, I must re-read…..

Can you help me find this: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4iO0-7GTY8g

Only one here I’m familiar with is “The Inner Light”. I was crazy for George’s Indian sound (I still am), used to play this tune every time I was at a place with a juke box. Good article,my first time on this very interesting site.